CHAPTER ONE

GETTING STARTED

As a leader, you can actively shape your organization. It is probably the most important role you have.*

The organization can't be designed from the bottom up. Those on the front lines don't have the broad perspective necessary for making the trade-offs that will affect the whole organization, whether that organization is the entire enterprise or a particular division or department. Although they can and should be involved in the design process to help identify the problems that need to be addressed and provide insight into what customers want, organization design is the responsibility of the leader and the leadership team.

This chapter provides an overview of the design process and explains how to effectively involve people from the organization in that process. It has five sections:

- Organization Design describes the components of organization design in terms of the “star model.”

- The Reconfigurable Organization defines the characteristics of organizations that can respond quickly and flexibly to changes in the environment.

- Deciding When to Redesign identifies those triggering events that are most likely to initiate a reconsideration of the organization's design.

- The Design Process provides an overview of the sequence of events in the design process.

- The Case for a Participative Process provides guidelines for involving others in the design process.

ORGANIZATION DESIGN

Organization design is the deliberate process of configuring structures, processes, reward systems, and people practices and policies to create an effective organization capable of achieving the business strategy.

Organization “design” is often used synonymously and incorrectly to mean organization “structure.” The organization design process and its outcome, however, are much broader than rearranging the boxes on the organization chart. The star model (Figure 1-1) is a framework for thinking holistically about the five major components of organization design. Each point on the star model represents a major component of organization design.1 When all points are in alignment, the organization is at its most effective. The structure, processes, rewards, and people practices all support the strategy. The star model serves as the organizing framework for this book and is discussed in detail in each chapter. To provide an overview, each point on the model is briefly defined next.

Figure 1-1. Star model.

Source: Jay R. Galbraith, Designing Organizations: An Executive Briefing on Strategy, Structure, and Process (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995).

STRATEGY

The strategy sets the organization's direction. The term is used broadly here to encompass the company's vision and mission as well as its short- and long-term goals. The strategy delineates which products and markets the company will pursue and, as important, those it will not pursue. The strategy specifies the source of competitive advantage for the organization and how the company will differentiate itself in the marketplace.

Strategy is the cornerstone of the organization design process. If the strategy is not clear, or not agreed upon by the leadership team, there are no criteria on which to base other design decisions. Without knowing the goal, it is impossible to make rational choices along the way.

STRUCTURE

The organizational structure determines where formal power and authority are located. It comprises the organizational components, their relationships, and hierarchy. It channels the energy of the organization and provides a “home” and identity for employees. The structure is what is shown on a typical organization chart.

Structural design presents a number of choices for grouping people together at each level of the organization. Typically, departments are formed around functions, products, markets, or regions and then configured into a hierarchy for management and decision making. As important as the structure itself are the roles within the structure. A key part of the design process is defining the responsibilities of each organizational component and clarifying how they are intended to interrelate. To use the metaphor of the human body, the structure is akin to the bones. It sets the shape of the organization and the frame around which everything else is arrayed. The organizational roles can be thought of as the organs and muscles—where the work gets done.

PROCESSES AND LATERAL CAPABILITY

Regardless of how well thought out the organization's structure, it will create some barriers to collaboration. Information and decision making must cross the borders created by the structure. These can be overcome by designing the lateral capabilities—the interpersonal and technological networks, team and matrix relationships, lateral processes, and integrative roles that serve as the “glue” that binds the organization together. To extend the human body metaphor, the lateral organization functions like the body's blood, lymph, and nerves—the connective tissues that transmit knowledge and resources to where they are needed. An organization's lateral capability is the extent to which it can utilize these mechanisms to enhance its flexibility and leverage all its resources.

The networks and processes of the lateral organization cut across department boundaries. They can be informal and reliant upon the relationships of individual managers or formalized into cross-organizational processes and team structures. They can be quickly reconfigured after a few months or they may be in place for years. Process and lateral capability allow the organization to bring together the right people, no matter where they sit in the structure, to solve problems, create opportunities, and respond to challenges.

REWARD SYSTEMS

Metrics help align individual behaviors and performance with the organizational goals. A company's scorecard and system for rewarding people communicate what the company values to employees more clearly than any written statement. The design of metrics and reward and recognition systems influences the success of all other design components.

PEOPLE PRACTICES

The people point on the star represents the collective human resources (HR) practices that create organizational capability from the many individual abilities resident in the organization. The strategy determines what types of skills, competencies, and other capabilities are required of employees and managers. Different strategies require different types of talent and different people management practices, particularly in the areas of selection, performance feedback, and learning and development.

Just as in a living organism, if any of the components of the star are not attended to in the organization design process, the result is misalignment. It means that different elements are working at cross-purposes and less than optimal performance will be achieved, as illustrated in Figure 1-2.

THE RECONFIGURABLE ORGANIZATION

The reconfigurable organization is able to quickly combine and recombine skills, competencies, and resources across the enterprise to respond to changes in the external environment.

Figure 1-2. Unaligned organization design.

Every company needs an organization that is as dynamic as its business. If not, the “ill-fitting coats” mentioned in the preface will restrict movement and flexibility and cause you to fall behind competitors. In order to keep from falling behind, many companies are devoting enormous amounts of time and energy to “change management.” This task can be made less difficult and less time-consuming if some of the change effort is focused on designing a more flexible organization from the outset. If change is constant, why not design the organization to be constantly and quickly changeable?

The reconfigurable organization is characterized by:

![]() Active Leadership. The reconfigurable organization has a leader and leadership team that believe their organization can be a source of competitive advantage. They see their task as designing and improving the organization, choosing and rewarding people who can contribute, and enabling them to deliver excellence. Organization redesign is considered a core competence.

Active Leadership. The reconfigurable organization has a leader and leadership team that believe their organization can be a source of competitive advantage. They see their task as designing and improving the organization, choosing and rewarding people who can contribute, and enabling them to deliver excellence. Organization redesign is considered a core competence.

![]() Knowledge Management. The reconfigurable organization is based on knowledge. Whether reconfiguring to take advantage of a new product opportunity or meet a client's demands for customization, the success of most companies today depends on their ability to quickly collect and share knowledge across organizational boundaries. Reconfigurable organizations not only use technology to allow their employees to operate virtually, they also use it to connect with suppliers, customers, and partners. They have the mechanisms and the culture that allow people to convert data into useable information and knowledge.?

Knowledge Management. The reconfigurable organization is based on knowledge. Whether reconfiguring to take advantage of a new product opportunity or meet a client's demands for customization, the success of most companies today depends on their ability to quickly collect and share knowledge across organizational boundaries. Reconfigurable organizations not only use technology to allow their employees to operate virtually, they also use it to connect with suppliers, customers, and partners. They have the mechanisms and the culture that allow people to convert data into useable information and knowledge.?

![]() Learning. Learning is essential for organizations that are dynamic and want to be easily reconfigurable. It starts with selecting people who have learning aptitude, who are resourceful and motivated to take on new challenges. It continues with providing them the feedback and tools that allow them to measure their performance against internal and external standards and share in the responsibility for increasing their own capabilities. The reconfigurable organization is a learning organization that rewards those who build and use knowledge.

Learning. Learning is essential for organizations that are dynamic and want to be easily reconfigurable. It starts with selecting people who have learning aptitude, who are resourceful and motivated to take on new challenges. It continues with providing them the feedback and tools that allow them to measure their performance against internal and external standards and share in the responsibility for increasing their own capabilities. The reconfigurable organization is a learning organization that rewards those who build and use knowledge.

![]() Flexibility. The reconfigurable organization is built upon the assumption that there will be change. As routine tasks are automated, more work is becoming project-based and focused around teams, deadlines, and deliverables. People may often participate on multiple teams simultaneously. Networks are actively fostered and valued to allow teams to form and reform around regions, functions, customers, products, processes, and projects. The reconfigurable organization attracts people who have a high tolerance for ambiguity, change, and unpredictability.

Flexibility. The reconfigurable organization is built upon the assumption that there will be change. As routine tasks are automated, more work is becoming project-based and focused around teams, deadlines, and deliverables. People may often participate on multiple teams simultaneously. Networks are actively fostered and valued to allow teams to form and reform around regions, functions, customers, products, processes, and projects. The reconfigurable organization attracts people who have a high tolerance for ambiguity, change, and unpredictability.

![]() Integration. The reconfigurable organization assumes that people will move around the organization. If they are specialists, they will be expected to apply their talents in many different arenas. If they are generalists, they will rotate through jobs and roles, learning how to operate in a variety of functions and businesses. People will understand how different parts of the organization work and they will feel a part of the whole.

Integration. The reconfigurable organization assumes that people will move around the organization. If they are specialists, they will be expected to apply their talents in many different arenas. If they are generalists, they will rotate through jobs and roles, learning how to operate in a variety of functions and businesses. People will understand how different parts of the organization work and they will feel a part of the whole.

![]() Employee Commitment. Much has been written on the new employee contract. In exchange for giving up job security, people want their work contribution to be recognized and rewarded appropriately. In addition, they want to be given the opportunity to learn skills that will be valued in the internal and external marketplace. They also want peers who are trained and capable of performing at high levels. The reconfigurable organization enables its employees to deliver excellence to its customers by providing the right tools, skills, and information. As a result, employees believe in the company's products and services, recommend it as a good place to work, and choose to stay longer with the company.

Employee Commitment. Much has been written on the new employee contract. In exchange for giving up job security, people want their work contribution to be recognized and rewarded appropriately. In addition, they want to be given the opportunity to learn skills that will be valued in the internal and external marketplace. They also want peers who are trained and capable of performing at high levels. The reconfigurable organization enables its employees to deliver excellence to its customers by providing the right tools, skills, and information. As a result, employees believe in the company's products and services, recommend it as a good place to work, and choose to stay longer with the company.

![]() Change Readiness. Change is difficult for everyone. Even when people acknowledge that change is necessary and that the end result will be better, the process can be demoralizing and stressful. Often, despite good intentions on the part of managers, people don't understand why change is occurring or why certain decisions have been made. It's not merely a communication problem. People are often told the reasons why a change is occurring. Usually, they're not convinced. It sometimes appears that managers are “rearranging the furniture” rather than making change for sound business reasons. In the reconfigurable organization, employees understand the design assumptions and are involved in the design process. When changes inevitably have to be made again, the mechanisms are in place to have the conversations, debate the options, and move forward with decisions. People may still experience individual negative impact, but the organization is no longer turned upside down by the change. It has developed resilience and collective competence in the process of organizational change.

Change Readiness. Change is difficult for everyone. Even when people acknowledge that change is necessary and that the end result will be better, the process can be demoralizing and stressful. Often, despite good intentions on the part of managers, people don't understand why change is occurring or why certain decisions have been made. It's not merely a communication problem. People are often told the reasons why a change is occurring. Usually, they're not convinced. It sometimes appears that managers are “rearranging the furniture” rather than making change for sound business reasons. In the reconfigurable organization, employees understand the design assumptions and are involved in the design process. When changes inevitably have to be made again, the mechanisms are in place to have the conversations, debate the options, and move forward with decisions. People may still experience individual negative impact, but the organization is no longer turned upside down by the change. It has developed resilience and collective competence in the process of organizational change.

Organizations have always been created to execute business strategies. The need for a reconfigurable organization arises from the decline in the sustainability of competitive advantage. Different strategies lead to different types of organizations. But when advantages do not last long, neither can the organizational forms created to execute them. In the past, managers crafted a winning business formula and erected barriers to entry that sustained this advantage. Then management created an organization—structured around functions, products/services, and markets or geographies—that was designed to deliver the success formula. After the structure was determined, the planning, information, and HR support systems would be designed and aligned with each other and with the organization's strategy and structure. The assumption was that there was plenty of time to implement these changes.

Today, in many industries, success formulas do not last very long. The advantages around which an organization is designed are quickly copied or even surpassed by alert and quick-to-react competitors. Worse, some companies find themselves cannibalizing their own advantages, setting up competitors internally to gain market share before external competitors do. By the time everything is aligned with the strategy, the strategy has changed. Therefore, you must have organizational structures and processes that are easily reconfigured and realigned to keep pace with a constantly changing strategy.

Major changes in the environment often cause panic in organizations. Managers react by “blowing up” the organization and starting all over, usually because they don't know which changes will have the desired impact. The reconfigurable organization is designed with intent. Decisions are made with awareness of the expected outcomes. Therefore, when change is necessary, a focused response to change can be made. The right lever can be pulled, whether changing the structure or roles, reconfiguring processes, or developing new skills. Changes are targeted and disruption is minimized.

The reconfigurable organization directs knowledge and information to where it is needed. It provides employees with opportunities to grow and learn. The organizations that can achieve this are those that are designed from the beginning to be quickly and easily adaptable. No longer will each redesign need to begin with a blank slate. Even a little success in designing a flexible, agile organization will go a long way toward reducing the enormous amounts of time, energy, and pain typically associated with change. Use Tool 1-1 to determine what areas in your organization need to be made more flexible and ready to respond to change.

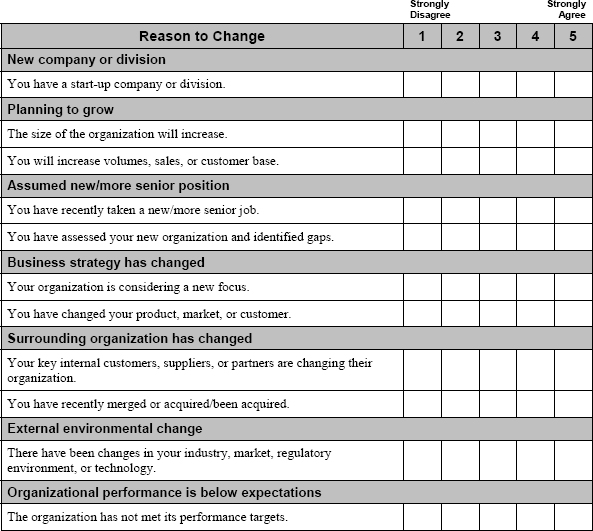

DECIDING WHEN TO REDESIGN

Various events can trigger an organization's need to redesign.

![]() You are starting up a new company or division. Clearly, a new business needs to be designed. Before launching Saturn, GM spent nearly three years planning the technology, systems, and organization that would be needed to launch a world class–quality small car that could compete successfully with imports. Saturn was to be not just a new car line but a whole new way of making and selling cars, with manufacturing processes, team structures, and compensation systems that are all different from those at the core GM company. Many start-up founders, however, don't think about organizational issues until the company has grown large enough to require it. Founders often wait until investors demand that they hire managers from established companies with some organizational experience before they pay any attention to creating an infrastructure.

You are starting up a new company or division. Clearly, a new business needs to be designed. Before launching Saturn, GM spent nearly three years planning the technology, systems, and organization that would be needed to launch a world class–quality small car that could compete successfully with imports. Saturn was to be not just a new car line but a whole new way of making and selling cars, with manufacturing processes, team structures, and compensation systems that are all different from those at the core GM company. Many start-up founders, however, don't think about organizational issues until the company has grown large enough to require it. Founders often wait until investors demand that they hire managers from established companies with some organizational experience before they pay any attention to creating an infrastructure.

![]() You are planning to grow. Changes in size should trigger a reassessment of the organization. Growth can mean more employees. It can also mean greater volumes, increased sales, or an extension into new markets, new channels, or new countries. Size can change the complexity or scale of the business. Of Fortune's list of the 100 fastest growing companies in 1999, about a fifth lost 60 to 90 percent of their value during the following twelve months, and almost half lost at least some value. Most suffered from not having the right infrastructure or people to support continued growth.2

You are planning to grow. Changes in size should trigger a reassessment of the organization. Growth can mean more employees. It can also mean greater volumes, increased sales, or an extension into new markets, new channels, or new countries. Size can change the complexity or scale of the business. Of Fortune's list of the 100 fastest growing companies in 1999, about a fifth lost 60 to 90 percent of their value during the following twelve months, and almost half lost at least some value. Most suffered from not having the right infrastructure or people to support continued growth.2

![]() You have just assumed a new or more senior position. New managers are often accused of changing the organization they've taken over simply to assert themselves. In order to justify the change in leadership, the old way of doing things is thrown out whether it worked or not. A new manager, however, should thoroughly appraise the current organization and make changes only if they are needed. The first few months on the job, the honeymoon period, is the best window of time to assess the landscape. If you use a structured process to understand the current organization and decide what needs to be modified, you will provide those in the existing organization with the confidence that changes are not being made arbitrarily or just for the appearance of change. As part of your assimilation process, you should assess the current organization to determine if it facilitates or hinders your strategy.3

You have just assumed a new or more senior position. New managers are often accused of changing the organization they've taken over simply to assert themselves. In order to justify the change in leadership, the old way of doing things is thrown out whether it worked or not. A new manager, however, should thoroughly appraise the current organization and make changes only if they are needed. The first few months on the job, the honeymoon period, is the best window of time to assess the landscape. If you use a structured process to understand the current organization and decide what needs to be modified, you will provide those in the existing organization with the confidence that changes are not being made arbitrarily or just for the appearance of change. As part of your assimilation process, you should assess the current organization to determine if it facilitates or hinders your strategy.3

![]() Your strategy has changed. If your products or markets have changed, or you are adding a new line of business, or you are expanding into international territory, it is likely that your organization needs to change as well. For example, the Coca-Cola Company announced a reorganization in the spring of 2001 in order to allow it to focus more on marketing juice, coffee, and tea through joint ventures.

Your strategy has changed. If your products or markets have changed, or you are adding a new line of business, or you are expanding into international territory, it is likely that your organization needs to change as well. For example, the Coca-Cola Company announced a reorganization in the spring of 2001 in order to allow it to focus more on marketing juice, coffee, and tea through joint ventures.

![]() The organization around you has just changed. The organization design process can be triggered by an internal realignment. If the level above has just reorganized and key internal customers, suppliers, or partners are changing, then your organization may need to change also. For example, when Deutsche Bank bought Bankers Trust, the Bankers Trust marketing function that supported products sold to institutional customers had to begin operating on a global scale. What had been a simple organization in New York now had to collaborate with Frankfurt and London and support new products and customers. The old organization was simply no longer effective.

The organization around you has just changed. The organization design process can be triggered by an internal realignment. If the level above has just reorganized and key internal customers, suppliers, or partners are changing, then your organization may need to change also. For example, when Deutsche Bank bought Bankers Trust, the Bankers Trust marketing function that supported products sold to institutional customers had to begin operating on a global scale. What had been a simple organization in New York now had to collaborate with Frankfurt and London and support new products and customers. The old organization was simply no longer effective.

![]() There has been a major change in the external environment. New competitors, new technology, and new regulations are some of the forces in the external environment that can trigger a reassessment of the organization. For example, the opportunity to automate manual processes not only reduces the number of people needed, it also impacts the skills that the remaining employees and their managers need to have. The premium that had been placed on processing accuracy and efficiency is replaced with value on complex problem-solving and exception-processing ability. On the regulatory front, when the Glass-Steagall Act, which had prohibited banks from combining with other types of financial services, was partially repealed in November 1999, it cleared the way for U.S. insurance companies and banks to acquire one another. These mergers and acquisitions have all been accompanied by organization redesigns.

There has been a major change in the external environment. New competitors, new technology, and new regulations are some of the forces in the external environment that can trigger a reassessment of the organization. For example, the opportunity to automate manual processes not only reduces the number of people needed, it also impacts the skills that the remaining employees and their managers need to have. The premium that had been placed on processing accuracy and efficiency is replaced with value on complex problem-solving and exception-processing ability. On the regulatory front, when the Glass-Steagall Act, which had prohibited banks from combining with other types of financial services, was partially repealed in November 1999, it cleared the way for U.S. insurance companies and banks to acquire one another. These mergers and acquisitions have all been accompanied by organization redesigns.

![]() Your organization isn't delivering the performance expected. Performance problems (customer complaints, loss of market share, missed financial targets, high turnover, etc.) are rarely the result of just one factor. Nor does addressing the most obvious symptom with a quick fix (training, marketing, cost cutting, compensation, etc.) usually address the underlying issues. Organization design is both a comprehensive and an integrative process that examines root causes of issues and directs organizational energy and change where it will have the most impact.

Your organization isn't delivering the performance expected. Performance problems (customer complaints, loss of market share, missed financial targets, high turnover, etc.) are rarely the result of just one factor. Nor does addressing the most obvious symptom with a quick fix (training, marketing, cost cutting, compensation, etc.) usually address the underlying issues. Organization design is both a comprehensive and an integrative process that examines root causes of issues and directs organizational energy and change where it will have the most impact.

Use Tool 1-2 to confirm your need to consider a redesign of your organization.

THE DESIGN PROCESS

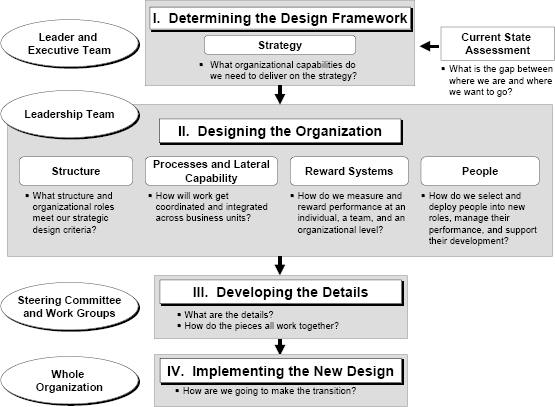

The star model provides a guide to the topics that are considered throughout the design process. Figure 1-3 shows how each of the points of the star model are addressed through the design process. Each of the four phases—Design Framework, Designing the Organization, Developing the Details, and Implementing the New Design—has a series of decisions and steps within it and requires participation by different groups and levels in the organization. Given that organization design is more an art than a science, however, the order of the steps and decisions will vary depending on the nature of the organization, the issues to be addressed, and who is involved in resolving them. Each phase in the figure is outlined below and subsequent chapters are devoted to describing the process and activities in each phase.

Figure 1-3. Four phases of organization design.

I. DETERMINING THE DESIGN FRAMEWORK

The Determining the Design Framework phase is the work of translating the strategy into design criteria. The outcome of this phase allows you to clearly communicate:

- Why do we need to change?

- Where do we need to go?

- What will the end state look like??

It is your responsibility as a leader to address these issues, although you will likely involve your executive team. This phase of work focuses on what organizational capabilities need to be developed in order to achieve the goals of the strategy. Other issues that are considered when setting the framework are the goals and boundaries of the change and determining the time frame for the process. A key input to the design framework is the Current State Assessment, which defines the gap between where the organization is today and the desired future state. A guide for assessing the current state is provided in Chapter Two.

II. DESIGNING THE ORGANIZATION

The Designing the Organization phase identifies those changes in the organization that need to be made to align the organization to the strategy. The outcome of this phase will be answers to these two questions:

- What is going to change?

- How will we get there?

The work of researching best practices and generating and evaluating options is usually done by the leadership team and includes topics such as:

- Determining the new organizational structure

- Defining new organizational roles

- Identifying the key lateral processes that need to be developed to support the structure

- Determining how teams and matrix relationships are intended to function, if they are to be incorporated

- Outlining the metrics that will be used to measure performance

- Deciding what HR practices will best support the new organization

By no means will all the details be worked out in this phase, but decisions will be made that chart a clear path to the new shape of the organization. Chapters Three through Six cover the major design decisions you will have to make.

III. DEVELOPING THE DETAILS

The elements of the design are fleshed out and refined during the Developing the Details phase. Here is where the work groups and steering committee usually take over from the leadership team to carry the work forward. The work groups create detailed project plans to develop the design elements as well as begin implementation.

IV. IMPLEMENTING THE NEW DESIGN

During implementation, the entire organization is involved as the new design is rolled out and put into practice. The development phase may overlap with the Implementing the New Design phase when pilot sites are used. Chapter Seven highlights some considerations for the development and implementation phases.

Rarely is an organization designed from a clean sheet of paper. Sometimes structural decisions have to be made to accommodate existing employees and roles have to be defined around the available pool of talent. Although this may not be ideal, the desired changes can be implemented in phases over time. Seldom is the organization ready to move to the end state all at once. As with most business decisions, the commitment to execution and follow-through is as important as the design decisions themselves.

The design process always begins with reviewing the strategy. However, this process is not linear. The design process needs to be as complex and integrated as the organization itself. It is hardly ever a simple decision tree. Rather, the process often loops back on itself because a decision in one arena impacts others. For example, the design of lateral processes may point out flaws with the underlying structure and trigger a reconsideration of how work units and departments are configured. In addition, cross-functional teams can't be configured without thinking through some elements of the metrics and compensation structure. Many of the steps in the design process should be considered concurrently. The power of the reconfigurable organization is evident when its design is considered in the context of strategy. Ask the question, “How can we organize to deliver on the strategy?” Thinking this way not only accelerates the process but turns organizational change from a lagging activity to one that is an integral part of the strategy.

The focus of your design process will be determined by the biggest gaps between where your organization is today and where it needs to go. Figure 1-4 summarizes some typical gaps and which part of the design process they will lead you to consider. Where you begin impacts the scope of the design and change process. A change in strategy and structure will require some realignment in all other parts of the star. On the other hand, a determination that the current structure is fine and better developed processes and roles will address the issues will narrow the scope of change. Chapter Two provides a guide to conducting a current state assessment of the organization and determining the underlying issues and priorities for change.

THE CASE FOR A PARTICIPATIVE PROCESS

You will need to make many decisions in the organization design process. Theoretically, as a leader, you and your executive team can make all the decisions. Usually, this is not practical or desirable for the successful implementation of those decisions. There are some good reasons to use a participative approach. By participative, we mean involving people in the organization beyond the executive team in identifying options and making decisions. True participation goes beyond soliciting input or informing people about decisions already made. It requires a leader to commit to accepting that a broader group will make some decisions. In many ways, participation is not a choice or “nice-to-have” option. The executive team often doesn't have enough details about the processes and jobs at the front line to make informed decisions regarding how to alter them. Participation doesn't imply that all decisions are taken out of the hands of the leader or that a broader group is involved at all points in the process. In fact, some decisions are the responsibility of the leader and shouldn't be delegated, particularly the up-front work regarding the strategy.

Figure 1-4. Choosing a starting point.

Nor does everyone need to have equal participation. Lower-level employees may participate either in focus groups or by communicating through representatives on work groups. Those identified as high potentials may be designated to lead work groups. Employees new to the organization may be called upon for their fresh ideas and experiences working in other environments. Employees with long tenure may be singled out to provide institutional memory to avoid repeating past mistakes.

Participation can take a number of forms in the design process:

- Identifying the current state and the gap between where the organization is today and what needs to change to achieve the strategy

- Researching and generating design options

- Evaluating and testing proposals

- Providing input and reacting to design alternatives

- Detailing and developing design decisions

- Creating implementation plans

Participation yields a number of benefits.

![]() More Ideas. The more people involved, the more ideas that are generated. In many organizations, people closest to the front lines, who deal firsthand with customers, technology, and process issues, have numerous untapped ideas. Often they can identify quick fixes that will have immediate impact.

More Ideas. The more people involved, the more ideas that are generated. In many organizations, people closest to the front lines, who deal firsthand with customers, technology, and process issues, have numerous untapped ideas. Often they can identify quick fixes that will have immediate impact.

![]() Commitment to Outcomes. People are more committed to decisions to which they feel they had input. If their suggestions and concerns have been genuinely heard and acknowledged, they will be more amenable to supporting directions with which they may not fully agree.

Commitment to Outcomes. People are more committed to decisions to which they feel they had input. If their suggestions and concerns have been genuinely heard and acknowledged, they will be more amenable to supporting directions with which they may not fully agree.

![]() Modeling New Relationships. Most organizational change initiatives have at least one objective focusing on building better working relationships among individuals and organizational units. If the participation process is structured to bring these groups together around the issues of design, new working relationships can be developed away from the heat of high-pressure business issues.

Modeling New Relationships. Most organizational change initiatives have at least one objective focusing on building better working relationships among individuals and organizational units. If the participation process is structured to bring these groups together around the issues of design, new working relationships can be developed away from the heat of high-pressure business issues.

![]() Developing High Potentials. Work groups are ideal forums for high-potential employees to learn about other parts of the organization and gain exposure to the organization's senior leadership. The design and refinement process can be used as a development assignment for high performers who are ready to be more broadly involved in the future of the company.

Developing High Potentials. Work groups are ideal forums for high-potential employees to learn about other parts of the organization and gain exposure to the organization's senior leadership. The design and refinement process can be used as a development assignment for high performers who are ready to be more broadly involved in the future of the company.

Participation is not appropriate when:

![]() The options are clear-cut. Involving a lot of people requires an investment of time, money, and energy. Time spent in meetings debating options is time away from the business. While involvement up front usually eases the implementation at the back end, sometimes it does not improve the outcome. If the issues are clear and there are few options to consider, it may be best for leadership to make the decisions and involve people in implementation planning rather than analysis or evaluation.

The options are clear-cut. Involving a lot of people requires an investment of time, money, and energy. Time spent in meetings debating options is time away from the business. While involvement up front usually eases the implementation at the back end, sometimes it does not improve the outcome. If the issues are clear and there are few options to consider, it may be best for leadership to make the decisions and involve people in implementation planning rather than analysis or evaluation.

![]() The decision should remain with the executive team. Setting the business strategy and direction are executive responsibilities and best not done by consensus. If the organization is small and there are sensitive personnel issues, a participative approach may not be appropriate. For example, if it involves asking people to eliminate their own positions and you have no alternatives for them, it's best to make the decisions yourself. People may be willing to tear down their own house and rebuild it with you; however, asking them to tear down their own house and remain homeless is cruel, not participative.

The decision should remain with the executive team. Setting the business strategy and direction are executive responsibilities and best not done by consensus. If the organization is small and there are sensitive personnel issues, a participative approach may not be appropriate. For example, if it involves asking people to eliminate their own positions and you have no alternatives for them, it's best to make the decisions yourself. People may be willing to tear down their own house and rebuild it with you; however, asking them to tear down their own house and remain homeless is cruel, not participative.

Participation is most successful when it is undertaken with clear parameters, when there is equitable representation, and when the process is structured and facilitated.

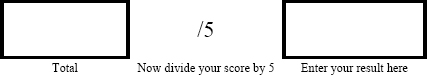

![]() Clear Parameters. Successful participation requires the leader to be absolutely clear about the parameters for decision making, the nonnegotiables, and the rules. Many times, the leader communicates the wrong expectations. He intends only to ask for input, but he fails to make explicit that involvement doesn't mean decision making by consensus. People are then disappointed when a decision contrary to their perspective is made. Figure 1-5 illustrates the range of participation choices in decision making from making the decision alone and selling it to the group (Option 1) to fully accepting a decision that the group makes (Option 4). Note that with Options 1 through 3, the final decision still rests with the leader. In fact, only Option 4 is actually a true participative decision.

Clear Parameters. Successful participation requires the leader to be absolutely clear about the parameters for decision making, the nonnegotiables, and the rules. Many times, the leader communicates the wrong expectations. He intends only to ask for input, but he fails to make explicit that involvement doesn't mean decision making by consensus. People are then disappointed when a decision contrary to their perspective is made. Figure 1-5 illustrates the range of participation choices in decision making from making the decision alone and selling it to the group (Option 1) to fully accepting a decision that the group makes (Option 4). Note that with Options 1 through 3, the final decision still rests with the leader. In fact, only Option 4 is actually a true participative decision.

Much confusion and misunderstanding arise when leaders use Options 1, 2, or 3 and raise expectations around participation and involvement but don't clarify that final authority still remains with the leader. The key is to match the right style to the circumstances. If Options 1 and 2 are used too often, the leader will be perceived as autocratic. However, full participation is not always appropriate. Used too often, it may represent an abdication of the leader's decision-making responsibility. Use Tool 1-3 to assess the conditions for participation in your organization.

![]() Equitable Representation. Most organizations are too big to involve everyone. Choosing some people and not others raises issues of equity. What is intended to be a participative process ends up creating divisiveness. For example, you want to use a work group to research and generate new reward and recognition options. By selecting the participants, you automatically create insiders. Whatever the group comes up with will be rejected by those who felt passed over. If you ask for volunteers, you may get only those with an ax to grind or those who perceive the assignment as a way to curry favor or get ahead.

Equitable Representation. Most organizations are too big to involve everyone. Choosing some people and not others raises issues of equity. What is intended to be a participative process ends up creating divisiveness. For example, you want to use a work group to research and generate new reward and recognition options. By selecting the participants, you automatically create insiders. Whatever the group comes up with will be rejected by those who felt passed over. If you ask for volunteers, you may get only those with an ax to grind or those who perceive the assignment as a way to curry favor or get ahead.

One way to avoid these outcomes is to use “representatives.” Announce the purpose of the work group and the general composition (e.g., ten people representing each of your five locations, four functional areas, and six levels) as well as the criteria for participation (e.g., skill level, tenure). Anyone who is interested may nominate himself or herself to be considered. The person's peers conduct a simple vote. If the results are lopsided (e.g., all women and no men) or if you want to add some particular perspectives for balance, make the adjustments before the results are announced.

Figure 1-5. Involvement options.

Adapted from T. D. Christenson, How to Decide… (South Bend, Ind.: STS Publishing, 1980).

Participants in this work group now speak for their level, location, or function rather than simply stating their own opinions. As representatives they should be required to reach out to others in their part of the organization to gather ideas and concerns. The recommendations of the work group are likely to be better received using this approach.

![]() Facilitated Process. Richard Hackman notes that the effectiveness of any group is equal to its potential productivity less the inevitable process loss inherent in group interaction.4 In other words, no matter how many good ideas the group has, they may be derailed by unresolved conflict, by group pressure to compromise rather than optimize decisions, or by a lack of process. Everyone has been in a meeting where it took longer to figure out how to proceed than to discuss the issue itself. Particularly for groups comprising people who don't know each other, haven't worked together before, or are at different levels, lack of process can get in the way of problem solving. Having a facilitator attend to the group process can improve the outcome significantly and build the group's skills in managing their own process in the future. The facilitator can be an external consultant or a skilled internal person. If internal persons are used, they should not be members of the group so that they can stay neutral and focus exclusively on managing the group dynamics and outcomes.

Facilitated Process. Richard Hackman notes that the effectiveness of any group is equal to its potential productivity less the inevitable process loss inherent in group interaction.4 In other words, no matter how many good ideas the group has, they may be derailed by unresolved conflict, by group pressure to compromise rather than optimize decisions, or by a lack of process. Everyone has been in a meeting where it took longer to figure out how to proceed than to discuss the issue itself. Particularly for groups comprising people who don't know each other, haven't worked together before, or are at different levels, lack of process can get in the way of problem solving. Having a facilitator attend to the group process can improve the outcome significantly and build the group's skills in managing their own process in the future. The facilitator can be an external consultant or a skilled internal person. If internal persons are used, they should not be members of the group so that they can stay neutral and focus exclusively on managing the group dynamics and outcomes.

The UNOPS case study in Chapter Three illustrates how to use a participative design process in more detail.

SUMMARY

In this chapter we have defined organization design using the star model as a conceptual way of thinking about all of the elements to consider, how they interrelate, and how they shape the design process. You have assessed how reconfigurable your own organization is and where you need to build the characteristics of the reconfigurable organization into your design. You've also confirmed the reason you are undertaking a redesign. Finally, this chapter has made the case for a participative design approach and provided guidelines for successfully involving others.

Chapter Two will help you determine the design framework by translating the strategy into a set of design criteria and assessing the current state of the organization.

NOTES

1. J. R. Galbraith, Designing Organizations: An Executive Briefing on Strategy, Structure, and Processes (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995), pp. 11–17.

2. “Growth Elixirs May Be Risky,” Fortune, September 4, 2000, p. 164.

3. D. Downey, T. March, and A. Berkman, Assimilating New Leaders: The Key to Executive Retention (New York: AMACOM, 2001), pp. 101–112.

4. R. J. Hackman and G. R. Oldham, Work Redesign (Reading, Mass.: Addison-Wesley, 1980), p. 176.

Tool 1-1. How reconfigurable is your organization?

| Purpose: | Use this tool to gain a preliminary perspective on how your organization responds to change. |

| This tool is for: | Executive Team. |

| Instructions: | A reconfigurable organization is one that is characterized by active leadership, knowledge management, learning, flexibility, integration, employee commitment, and change readiness. Each of these characteristics is defined by three statements below. For each one, rate your organization by how strongly you agree (“5”) or disagree (“1”) with the statement. Then, total your scores. |

Now, enter your totals for each area below (your scores should all be between 3 and 15):

Lower numbers indicate areas of greater concern as you proceed through the organization design process. Similarly, higher numbers are strengths you can build on going forward. Continue to use this tool when questions arise as to how flexibly your organization can respond to changing strategic imperatives. Return to it to diagnose your progress as you implement change.

Tool 1-2. Reasons to redesign.

| Purpose: | This tool confirms your reasons to redesign and will help you communicate the purpose of the change effort. |

| This tool is for: | Executive Team. |

| Instructions: | You have just read about the key reasons behind an organization redesign. Now, examine your own reasons for redesigning. For each item below, rate the extent to which you believe this item is a factor behind an organization redesign by how strongly you agree (“5”) or disagree (“1”) with the statement. |

What are your top three reasons for changing?

1. ________________________________________________________________

2. ________________________________________________________________

3. ________________________________________________________________

Tool 1-3. Determining participation.

| Purpose: | This tool will help you identify which participatory style is appropriate for your redesign effort. |

| This tool is for: | Leader. |

| Instructions: | You have read about the potential benefits and pitfalls of participatory approaches in implementing organization design efforts. You have also examined the four key involvement options (sell, test, consult, participate) that will dictate your participation style in an organization design effort. Refer to Figure 1-5 in the text as you complete this worksheet. Below are five dimensions that will impact the leader's extent of involvement in the design process. For each dimension, circle the rating that reflects your organizational situation. |

Total your ratings. Transfer your total score into the box at left below. Then divide your total by five and enter the result in the box at right below.

Transfer your final result onto the scale below. This will help you determine the involvement option that is best for you at this time.

![]()

*Leader and manager are used interchangeably in this book. Although some argue that there are clear differences in the roles, the differences usually depend upon perspective. The tasks of a midlevel manager in a large company would be “management” activities (e.g., focusing on short-term time frames, details, eliminating risks, keeping the organization on time and on budget) compared with those of senior executives. However, for the people who report to that manager, he is their “leader” and expected to act like one (focusing on the big picture, communicating values, motivating and inspiring people, and championing and creating change). For more on the differences between managers and leaders, see J. P. Kotter, Force for Change: How Leadership Differs From Management (New York: The Free Press, 1990).