CHAPTER SIX

PEOPLE PRACTICES

People practices are the collective human resources (HR) systems and policies of the organization. They include selection and staffing, performance feedback and management, training, development, and careers. Up to this point in this book, we have discussed how to align the organization's structure, processes, and metric and rewards to the strategy. People practices are the final point on the star model (Figure 6-1). However, this is not to imply that the consideration of people comes last in the design process. Staffing the organization is an issue that will arise as soon as any structural changes are contemplated. In fact, getting the right senior team in place may be one of your first priorities and a key factor in the success of the design and implementation process.

A challenge in designing dynamic organizations is to create systems that will attract, develop, and retain people whose individual and collective capabilities can support the current direction and yet who are flexible enough to be refocused and redeployed when that direction changes. We made the point in the preface of this book that having the right people won't compensate for the lack of other essential organizational elements. Their talent will be wasted if the structure, processes, and metrics dissipate their energy and create barriers to their collective effectiveness. On the other hand, no matter how well designed, no business can realize its goals without the right people in place—people with the right mind-set, skills, and ability to grow and learn with the organization.

In Chapter Two we looked at how each strategic focus—product, operations, customer—leads to different processes, measures, and culture (refer back to Figure 2-2). Different strategies also imply that different types of people will succeed in the organization. Every business wants to hire smart, experienced, and hard-working people. But such generalizations don't differentiate enough among candidates to identify who is likely to make the critical contributions to help your business achieve competitive advantage.

Figure 6-1. Star model.

Source: Jay R. Galbraith, Designing Organizations: An Executive Briefing on Strategy, Structure, and Process (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1995).

Reconfigurable organizations are able to adapt quickly to a dynamic marketplace that requires shifts in the strategic focus of the business. As the organizational definition of success changes, so will the skills, knowledge, and behaviors required. Any system or process you design, therefore, must be capable of responding quickly to changes in the direction of the business without sacrificing the integrity of the system itself. The goal is not to be continually changing your organization's HR systems, but to create aligned systems that contribute to organizational flexibility and responsiveness.

Figure 6-2 illustrates how each HR system can support a reconfigurable organization design. Assessment and selection processes ensure the right people are hired, not only for the work that must be done today, but for the future as well. Different organizations require different skill sets, but all reconfigurable organizations need learning-agile people willing to accept that their assignments will change and priorities be reordered. Performance feedback mechanisms not only provide the basis for compensation, rewards, and recognition, but they provide employees with the information they need to take control of their own learning and development. Many companies are supplementing supervisor-centered feedback with the use of peer and upward feedback to give a fuller and more actionable picture of performance and to reflect the importance of the work occurring through the lateral organization. Learning and development and the management of knowledge have become key enablers for the organization. Learning also has become the new currency used in the employee contract. A promise of job security is replaced with the opportunity for developing skills and knowledge that will be valued within the organization and in the external talent marketplace. Rewards and recognition are the link between the metrics that define organizational success and individual contribution.

Figure 6-2. An integrated model of people practices.

Compensation systems that reward high performance, as discussed in Chapter Five, help attract and retain the right people to the organization. Dynamic, reconfigurable organizations are characterized by people practices that support learning and the development of strategically important capabilities.

This chapter is not a comprehensive review of all the decisions that need to be made in the design of HR systems. There are many important decisions to be made regarding sourcing, recruiting, and hiring; orientation, assimilation, training, development, and career paths; goal setting and performance appraisal; and HR policies in the areas of employee relations, diversity, and work environment—to list just a few. Rather, this chapter highlights the areas that are most likely to create the behaviors and mind-sets that support reconfigurability. The chapter has four sections:

- Staffing the New Organization presents principles and tools to guide the process of placing people into new roles and positions.

- Assessing for Learning Aptitude presents a way to select for learning-agile candidates.

- Performance Feedback reviews the ways in which multidirectional feedback can support building lateral capability.

- From Training to Learning provides a checklist of the best practices that many organizations are utilizing to create a learning organization.

STAFFING THE NEW ORGANIZATION

The most immediate concern of the employees in an organization going through a redesign is, “Where am I going to end up?” Until this question is answered, there will be a high degree of uncertainty and anxiety in the organization that can distract people from their work and lower productivity. We recommend that leaders announce as soon as possible the process they will be using for placing people in new positions, even if the structure and roles are still in the design phase. Letting people know how decisions will be made will minimize the rumors that can build during a design process.

PRINCIPLES

When staffing the new organization there are some key principles to keep in mind.

![]() Fill senior positions first. Gaps on the executive team or any changes that are contemplated due to new roles or required skills should be dealt with as soon as possible in the design process. This way the new executive team can contribute to the overall design and take responsibility for designing and staffing their own organizations as a new, aligned executive team.

Fill senior positions first. Gaps on the executive team or any changes that are contemplated due to new roles or required skills should be dealt with as soon as possible in the design process. This way the new executive team can contribute to the overall design and take responsibility for designing and staffing their own organizations as a new, aligned executive team.

![]() Conduct the staffing process quickly. It will take some time before you are ready to staff. You will need to fully design the new structure and roles and develop profiles of what the successful candidate should look like. However, once the staffing process is under way, it should be completed as quickly as possible and announcements made. In this way people will know where they stand and can begin planning the transition to their new roles.

Conduct the staffing process quickly. It will take some time before you are ready to staff. You will need to fully design the new structure and roles and develop profiles of what the successful candidate should look like. However, once the staffing process is under way, it should be completed as quickly as possible and announcements made. In this way people will know where they stand and can begin planning the transition to their new roles.

![]() Balance risk. You might be tempted to reduce risk for the new organization by placing people only in roles where they can fully perform to the new requirements. It is unlikely, however, that you'll have the right profiles available in your current organization or even obtainable through hiring. You'll need to take some risks by placing people in roles for which they are not fully ready. Don't shy away from putting some people in positions that require growth and development if they have demonstrated potential and learning aptitude. Just be sure that if an assignment will be a stretch for a person, their skill or experience deficits are counterbalanced by someone else (a manager, team member, or colleague) who has strength in those areas. After making your initial staffing plan, revisit the balance of skills across locations, units, and teams and make adjustments to create strong working groups.

Balance risk. You might be tempted to reduce risk for the new organization by placing people only in roles where they can fully perform to the new requirements. It is unlikely, however, that you'll have the right profiles available in your current organization or even obtainable through hiring. You'll need to take some risks by placing people in roles for which they are not fully ready. Don't shy away from putting some people in positions that require growth and development if they have demonstrated potential and learning aptitude. Just be sure that if an assignment will be a stretch for a person, their skill or experience deficits are counterbalanced by someone else (a manager, team member, or colleague) who has strength in those areas. After making your initial staffing plan, revisit the balance of skills across locations, units, and teams and make adjustments to create strong working groups.

![]() Make the process transparent. The more people understand how decisions will be made, the more likely they will accept the decisions and move forward. An open process, where the criteria and position requirements are clearly stated, will also help avoid any legal challenges based on adverse impact. Given that placing people in new positions is such a sensitive topic with intense personal impact, the staffing process itself should mirror the organization's values and new way of operating.

Make the process transparent. The more people understand how decisions will be made, the more likely they will accept the decisions and move forward. An open process, where the criteria and position requirements are clearly stated, will also help avoid any legal challenges based on adverse impact. Given that placing people in new positions is such a sensitive topic with intense personal impact, the staffing process itself should mirror the organization's values and new way of operating.

INFORMATION TO CONSIDER

A range of information can be used to assess your current staff members against new role requirements. Much of this will be built upon the work you did in Chapter Three on defining and clarifying organizational roles. That work can be used as the basis to create job specifications. Some of the tools you can use to assess people for new roles include:

![]() Assessment Interview. An assessment interview is an approximately two-to three-hour in-depth interview structured to allow people to discuss past work accomplishments and how they approach different types of situations. The interviewer listens for patterns, not only of results but of how work is approached. An assessment interview also assesses learning aptitude. For each competency area required by the new role, the persons are asked to describe a time when they used or demonstrated the competency, the challenges they faced, and what they learned and applied from the experience. This is often a critical component of the assessment process, because new roles frequently require people to learn a significant number of new skills quickly.

Assessment Interview. An assessment interview is an approximately two-to three-hour in-depth interview structured to allow people to discuss past work accomplishments and how they approach different types of situations. The interviewer listens for patterns, not only of results but of how work is approached. An assessment interview also assesses learning aptitude. For each competency area required by the new role, the persons are asked to describe a time when they used or demonstrated the competency, the challenges they faced, and what they learned and applied from the experience. This is often a critical component of the assessment process, because new roles frequently require people to learn a significant number of new skills quickly.

An assessment interview can be conducted by an internal or external interviewer. The advantages of external assessors when making staffing decisions (as opposed to a purely developmental assessment) include:

—Time saved and a condensed staffing process timeline

—Consistency across interviewers

—Objectivity and elimination of bias based on past experience

![]() Knowledge and Skills Audit. An assessment interview focuses on accomplishments and competencies, not necessarily skills and knowledge. If technical knowledge is important or difficult to obtain, then ideally an objective assessment should be made of each person's skill level as well.

Knowledge and Skills Audit. An assessment interview focuses on accomplishments and competencies, not necessarily skills and knowledge. If technical knowledge is important or difficult to obtain, then ideally an objective assessment should be made of each person's skill level as well.

![]() Past Performance Reviews. If past performance data is robust and reliable, it can be a valuable source of information. However, since they were conducted against different role requirements and standards, performance reviews, even if positive, may have limited value.

Past Performance Reviews. If past performance data is robust and reliable, it can be a valuable source of information. However, since they were conducted against different role requirements and standards, performance reviews, even if positive, may have limited value.

![]() Mobility. If the organization has multiple locations, ability and willingness to relocate will be a factor in placement decisions.

Mobility. If the organization has multiple locations, ability and willingness to relocate will be a factor in placement decisions.

BENEFITS OF A STRUCTURED PROCESS

Although any restructuring process that results in people being let go—either through the elimination of jobs or as a result of changed skill requirements—is painful for all involved, using a structured process can provide a number of benefits for your organization:

![]() Decisions Based on Common Criteria, Not Horse Trading. When staffing decisions are made without criteria, an executive team can easily get into conflicts over choice candidates. A more forceful player may prevail in assembling talent that would be better placed elsewhere in the organization. A facilitated decision-making meeting with agreed-upon ground rules ensures that decisions are made for the good of the organization. Although members will champion certain candidates based on their own experience working with a person, and heated debate will certainly precede a number of decisions, the outcome will be agreements that everyone can live with.

Decisions Based on Common Criteria, Not Horse Trading. When staffing decisions are made without criteria, an executive team can easily get into conflicts over choice candidates. A more forceful player may prevail in assembling talent that would be better placed elsewhere in the organization. A facilitated decision-making meeting with agreed-upon ground rules ensures that decisions are made for the good of the organization. Although members will champion certain candidates based on their own experience working with a person, and heated debate will certainly precede a number of decisions, the outcome will be agreements that everyone can live with.

![]() Strengthened Executive Team. The process allows the executive team to engage what can be an emotional, contentious topic as a unified group. No simulated decision can serve as a better “team-building” exercise. The executive team builds skills in assessment and selection that can be applied in future recruiting and staffing. More important, they build the skill of working as a true team, able to rise above their individual concerns to make decisions for the whole organization utilizing their collective knowledge.

Strengthened Executive Team. The process allows the executive team to engage what can be an emotional, contentious topic as a unified group. No simulated decision can serve as a better “team-building” exercise. The executive team builds skills in assessment and selection that can be applied in future recruiting and staffing. More important, they build the skill of working as a true team, able to rise above their individual concerns to make decisions for the whole organization utilizing their collective knowledge.

![]() Information on Skill and Knowledge Gaps. A list of development needs is compiled as an outcome of the assessment process. This can serve as the basis for individual development-planning discussions between individuals placed in new roles and their managers. In addition, by looking at all the assessments, the executive team can identify gaps that are common across the organization. This minineeds assessment can point out areas where training or other broad-based development may have high impact.

Information on Skill and Knowledge Gaps. A list of development needs is compiled as an outcome of the assessment process. This can serve as the basis for individual development-planning discussions between individuals placed in new roles and their managers. In addition, by looking at all the assessments, the executive team can identify gaps that are common across the organization. This minineeds assessment can point out areas where training or other broad-based development may have high impact.

![]() Increased Internal Mobility. Once the executive team has reviewed all of the talent in the organization, it is more likely that an internal candidate will be considered when a promotion or developmental assignment becomes available. Often internal candidates are not considered for positions outside their own business unit because they are not visible to other senior managers. Many organizations are beginning to conduct yearly talent inventories to make executives aware of up-and-coming high performers who may be ready for their next move.

Increased Internal Mobility. Once the executive team has reviewed all of the talent in the organization, it is more likely that an internal candidate will be considered when a promotion or developmental assignment becomes available. Often internal candidates are not considered for positions outside their own business unit because they are not visible to other senior managers. Many organizations are beginning to conduct yearly talent inventories to make executives aware of up-and-coming high performers who may be ready for their next move.

![]() A Plan and Process for Recruiting. The tools used for internal staffing can be modified for assessing external candidates to fill empty positions. The benefit is that the same standards are being applied externally and internally, and that all interviewers are using the same decision-making criteria.

A Plan and Process for Recruiting. The tools used for internal staffing can be modified for assessing external candidates to fill empty positions. The benefit is that the same standards are being applied externally and internally, and that all interviewers are using the same decision-making criteria.

![]() Minimized Adverse Impact or Legal Action. The openness of the process helps to avoid legal challenges. Of course, any staffing process should take place with the guidance of the organization's employment specialists to provide advice on legal issues.

Minimized Adverse Impact or Legal Action. The openness of the process helps to avoid legal challenges. Of course, any staffing process should take place with the guidance of the organization's employment specialists to provide advice on legal issues.

![]() An Energized, Focused Group of Employees. One of the determinants of employee commitment is a person's satisfaction with the competence of coworkers. Knowing that one's colleagues have the skills to do the work, especially in team settings, gives a person confidence that the organization cares about the quality of work and wants to enable people to perform at their best.

An Energized, Focused Group of Employees. One of the determinants of employee commitment is a person's satisfaction with the competence of coworkers. Knowing that one's colleagues have the skills to do the work, especially in team settings, gives a person confidence that the organization cares about the quality of work and wants to enable people to perform at their best.

An example of how one company staffed a redesigned HR function will illustrate how these principles can be put into practice as well as present the tools that you can use when planning to staff your own organization. This case emphasizes how an open, structured staffing process can provide a firm foundation at a critical point in the design and begin to accelerate the implementation process. With a little imagination, the process can be modified to fit a variety of situations. The objective is to build organizational capability and tools that can be reused when the organization needs to be reconfigured again or new roles need to be crafted and staffed.

A groLife is a large and well-established insurance company. It sells life, disability, home, auto, dental, annuities, and other products to both individuals and businesses under a number of brand names. It has more than 20,000 employees located in sales offices and operations centers across the United States. Through its long and stable history, AgroLife had been legally structured as a mutual company. Under mutual ownership, shares are held by policyholders rather than traded in the open market, as is the case with a public company. The repeal of major sections of the depression-era Glass-Steagall laws, which had kept banking, insurance, and securities businesses separate, spurred a number of insurance companies to consider converting to public companies in the late 1990s. Once public, they would have access to capital through the equity markets, which would allow them to grow and diversify through mergers or acquisitions.

As AgroLife began to prepare itself to go public, Wall Street analysts made clear that the company would have to make some major changes if its stock was to perform well. Although the company had a well-known brand, an extensive distribution network, and a solid mix of products, it would be held back by what the analysts termed a “mutual culture.” The company's focus on stability and the lack of external scrutiny under mutual ownership had resulted in low productivity, high expenses, and a low tolerance for risk and change. Advancement was largely based on seniority. Beyond technical training, development was minimal. Many employees had worked at AgroLife their whole careers, with little feedback or few consequences for their performance. The company's image in the employment marketplace was as an unexciting, stodgy company providing few advancement opportunities. Although its sales positions continued to be attractive, AgroLife had trouble competing with dot-coms and other financial service companies for technology, marketing, and product development talent.

The chairman of AgroLife decided to use demutualization as a catalyst for transforming the organization. Managing for performance would become an enterprise-wide theme and a way to change the culture from one of complacency to one of urgency and high performance. Central to this effort would be HR. However, the HR function would first need to transform itself from the company's personnel department to a business partner prepared to lead this change. A new director of HR was hired, who reported directly to the chairman. She set about redesigning her organization.

HR at AgroLife had been structured into six regional offices, each supporting a range of businesses and locations in that region. Many of the HR staff had started their career at AgroLife in entry-level administrative positions and had moved into HR with little or no HR training or background. Many had never worked anywhere else or had never seen a different model of HR. Much of their time was devoted to transaction processing—new hires, payroll issues, benefit changes—and handling employee concerns. The regional staff had little direct connection with or in-depth knowledge of the businesses they supported. Difficult problems were referred to specialized compensation, benefits, and employee relations units at company headquarters. Given the low skill level in the organization, the new HR director decided to involve only her executive team in the redesign. Most of these people had strong skills and experience.

The design process was accomplished over a period of two months and resulted in a vision of a new organization ready to lead AgroLife forward. The HR function's strategy would be to “add value by building and maintaining the enterprise's organizational capabilities.” A particular focus would be creating new performance management and compensation systems that would differentiate and reward high performers. HR would have to help the line managers identify new performance metrics and coach them on making hard decisions regarding the people in their units. Building a new performance culture required a completely new role for HR and a new set of skills for the HR staff. To guide the executive team, five design criteria were identified. The new organization would need:

- Clear accountability in roles and responsibilities

- Knowledgeable staff able to respond to specific business unit strategies

- Common policies, procedures, and processes where appropriate to leverage best practices and provide consistency

- The ability to meet service expectations cost effectively

- The ability to flexibly adapt to changes in the business and advances in technology

The executive team's design featured a customer-oriented structure and new organizational roles.

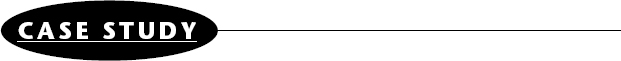

1. The regional structure was replaced with a customer structure. Each AgroLife line of business was given a dedicated team of HR professionals (Figure 6-3). Business managers now had a single point of contact for all their HR issues.

2. HR was expanded from six locations to twenty in order to support the larger operational sites that would benefit from on-site HR staff.

3. Two new roles were defined: generalist and senior generalist. Performance expectations in these roles were set high. Although the business managers were not ready to utilize HR as a full partner, the new roles anticipated the skills HR staff would need to build credibility and contribute to the business. These included being able to diagnose issues, develop solutions, and coach and influence line managers in a wide range of HR topics.

4. A new HR service center was established along with intranet-based self-service technology to handle all transaction processing. This would provide HR generalists with significantly more time to pursue value-added work and build relationships with line managers.

Figure 6-3. AgroLife HR structure.

5. Specialized units for employee relations, benefits, compensation, and strategic staffing remained at headquarters. Their focus shifted from front-line problem solving to policy, program development, and building the skills of HR generalists in the field.

With a vision in place of the how the organization would operate, and the new structure and roles defined, the next challenge facing the HR director was how to redeploy her existing staff into the new generalist roles supporting the businesses. The new structure anticipated seventy-five positions, of which approximately sixty were generalist positions and fifteen were senior generalist positions. This was an increase from the fifty-seven people currently in the regional structure. She and her executive team wanted a process that would work for placing existing staff as well as for assessing external hires. They decided to assess each existing staff member against the new role requirements using:

![]() Assessment Interviews. For AgroLife, the interview protocol was constructed around the competencies required by the generalist and senior generalist roles, including client service, process management, people management, teamwork and partnership, influence, and analysis and problem solving. The AgroLife HR executive team decided to have five external assessors skilled in talent assessment and familiar with the requirements of progressive HR organizations conduct two-hour assessment interviews with each person in order to save time and ensure objectivity.

Assessment Interviews. For AgroLife, the interview protocol was constructed around the competencies required by the generalist and senior generalist roles, including client service, process management, people management, teamwork and partnership, influence, and analysis and problem solving. The AgroLife HR executive team decided to have five external assessors skilled in talent assessment and familiar with the requirements of progressive HR organizations conduct two-hour assessment interviews with each person in order to save time and ensure objectivity.

![]() Knowledge and Skills Self-Audit. Given the broad range of HR knowledge required by the generalist roles, it would have been an expensive process for AgroLife to assess individual competence. In addition, the executive team determined that gaps in knowledge could be filled through training and development, and it was more important to focus the assessment process on underlying competencies and capabilities. Therefore, the skill assessment was administered as a self-audit. Each person rated himself or herself on a scale of one to five for over seventy knowledge areas, grouped under the topics of employment law, employee relations, compensation, benefits, HR management, change management, recruiting, career management, training, and technology. This information was mainly used as the basis for creating development plans for those that were placed in new positions.

Knowledge and Skills Self-Audit. Given the broad range of HR knowledge required by the generalist roles, it would have been an expensive process for AgroLife to assess individual competence. In addition, the executive team determined that gaps in knowledge could be filled through training and development, and it was more important to focus the assessment process on underlying competencies and capabilities. Therefore, the skill assessment was administered as a self-audit. Each person rated himself or herself on a scale of one to five for over seventy knowledge areas, grouped under the topics of employment law, employee relations, compensation, benefits, HR management, change management, recruiting, career management, training, and technology. This information was mainly used as the basis for creating development plans for those that were placed in new positions.

![]() Past Performance Reviews. Since the role expectations had changed so radically for AgroLife HR, and since performance expectations had been so low in the past, performance review results were used only as a secondary factor in decision making.

Past Performance Reviews. Since the role expectations had changed so radically for AgroLife HR, and since performance expectations had been so low in the past, performance review results were used only as a secondary factor in decision making.

![]() Mobility Data. The AgroLife HR organization structure established HR offices in fourteen new locations around the United States. Staffing decisions considered each individual's willingness to relocate.

Mobility Data. The AgroLife HR organization structure established HR offices in fourteen new locations around the United States. Staffing decisions considered each individual's willingness to relocate.

An overview of the process, the role profiles, assessment interview questions, and knowledge and skill self-audit, were distributed to all fifty-seven people two weeks before the interviews were to take place. The intent was to provide as much information to the staff as possible to ensure that there would be no surprises during the interview and to alleviate anxiety about the staffing process. The goal was to allow each person to have an equal opportunity to describe his or her skills and experience in the best light possible.

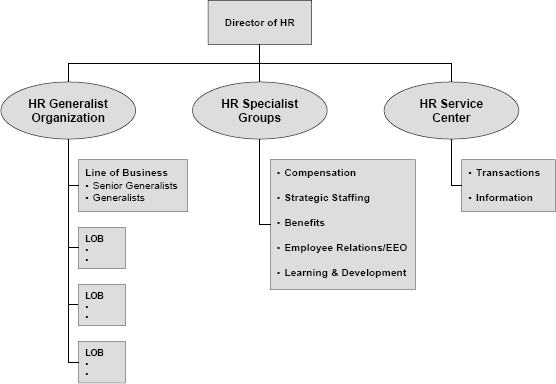

The interviews were held over a three-week period. After the interviews were completed, the external assessment team summarized the recommendations for each person in a standard format. In addition to a placement recommendation, each form provided the interviewer's rationale for the recommendation, the suggested development actions, a summary of accomplishments, and a listing of strengths and development needs based upon the interviewer's assessment. This information, together with the self-audit results, past performance reviews, and mobility were compiled into a binder for each member of the executive team. Figure 6-4 shows how the form was organized, including instructions to the assessors.

As soon as the data was compiled, a two-day facilitated decision-making meeting was scheduled for the executive team. During this meeting, each internal candidate was reviewed and a determination made. Only thirty-seven of the fifty-seven existing staff were offered positions in the new organization. The remaining twenty were transitioned out, either immediately or as they finished project work. Many were able to find positions elsewhere in the organization where they could use their transaction and administrative skills. Following the meeting, the executive team immediately flew to each of the regional centers to speak with each person individually, face-to-face, and to discuss the results of the staffing process.

It was obviously a difficult decision for the executive team to let go 35 percent of the AgroLife HR organization, especially since many of them were hard-working, long-tenured employees who had performed adequately under the old, lower expectations. The openness of the process, however, made it easier on everyone. As one person who was let go at AgroLife commented, “By the end of the process I knew I wasn't right for the new job. I wasn't happy, but at least there were no surprises.”

![]()

Use Tool 6-1 as a checklist when planning your own staffing process.

ASSESSING FOR LEARNING APTITUDE

Learning aptitude is a measure of a person's desire and aptitude to draw meaning from past experiences, and to utilize these lessons creatively to master new challenges.1 A new organization design requires more than new skills. It also requires that people learn new roles, build new relationships, acquire new knowledge, and apply all of this learning to new situations. Even then, learning will be required as the work continues to change in response to shifts in business strategy, markets, customers, competition, and technology. In the case of AgroLife, the ability to discern the current staff's aptitude for learning was a critical part of the assessment process because many people's current transaction-processing skills and knowledge would be irrelevant for the new HR roles.

Figure 6-4. Assessment summary sheet.

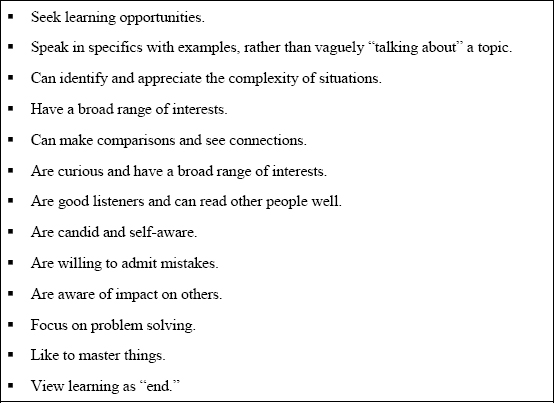

Companies need people with learning aptitude who:

- Fit the organization, not only the job.

- Bring an ability to learn, in addition to current knowledge.

- Have organizational savvy, not just technical knowledge.

A change in the organization structure provides an opportunity to bring new people into the organization to help lead it forward; people who possess the mind-sets, skills, and characteristics needed by the new organization. Many existing employees will be able to make the transition with some support, but some will be neither willing nor able to make the personal changes required to meet the expectations of the new organization.

How do you sort those who have learning aptitude from those who don't? People high in learning aptitude tend to display agility in four areas:

- Mental: They think through problems from a fresh point of view and are comfortable with complexity, ambiguity, and explaining their thinking to others.

- People: They know themselves well, are open to personal change, and treat others constructively; they understand how the politics of organizations and systems work.

- Change: They are curious, have a passion for ideas, and like to experiment; they are resilient under the pressures of change.

- Results: They get results under tough conditions, inspire others to perform, and are willing to challenge the status quo.

Learning-agile people share some characteristics no matter what type of job they are in (Figure 6-5). They see the gaps between their own behaviors and desired results and are able to look at their own experiences and assess what needs to change. Many organizations use competencies as a basis for identifying the general skills, knowledge, and ability that one needs to succeed. Learning is the “superordinate” competency, the one that enables a person to fully develop all others.

Knowledge-intensive businesses are particularly dependent on their ability to identify and hire people who have high learning aptitude. In the late 1990s, Ernst & Young Consulting Services found that the types of skills and knowledge that customers required of consultants were changing rapidly. Many of the firm's clients were installing complex enterprisewide information technology systems, such as SAP, Oracle, and PeopleSoft. These projects represented significant growth opportunities for the firm and required cutting-edge technical knowledge as well as client, consulting, and project management skills. The firm had also taken on a portfolio of Y2K business—projects to ensure that its client's legacy computer systems would not crash as the calendar changed from 1999 to 2000. These projects required a different set of skills and were of a limited duration. Given the difficulty in predicting the mix of work after 2000, the firm was eager to hire people who were willing and able to learn new skills and would provide a more flexible pool of talent to draw upon in a very dynamic market. As a result, the ability to learn from experience was embedded into Ernst & Young's recruiting and selection process to ensure that new hires met this requirement.

Figure 6-5. Characteristics of learning-agile people.

How do you assess for learning aptitude? An assessment for learning aptitude can be incorporated into any behavioral interview. A person is asked to describe a particular situation that relates to a desired competency (e.g., planning, decision making, customer relations). For each situation, the person is asked four questions:

- How did you approach it?

- Why did you do it that way?

- What did you learn from this experience?

- Can you give me some examples of how you applied what you learned in this situation to another situation?

Listen for evidence that the person:

- Grasped a learning dilemma.

- Can tell how and why they did something.

- Learned something new.

- Can articulate what they learned.

- Has applied what they learned to a new situation.

From these interviews, evidence of learning barriers and behaviors emerge and form a basis for comparison between candidates. Indicators are shown in Figure 6-6.

Figure 6-6. Learning barriers and behaviors.

The example below is from a transcript with Tom, a general manager for a personal computer manufacturer. Tom is in charge of all operations for one European country. Previously he had been a marketing director. This is his first general manager job with a full scope of responsibility. As part of a restructuring, he is being considered for a broader management position. The excerpt is taken from the portion of the interview that focuses on how Tom manages control issues.

Interviewer: Tell me about a time when things got out of control.

Tom: Unfortunately, although our products are the latest technology, some of the assembly machines are pretty old. They've been retrofitted. In the course of two months Station Five and Station Six broke down. The plant manager made some quick purchases that ended up costing us $10 million. And with my lack of experience in manufacturing it didn't click in my head, that if these machines are down now, and we're buying stuff from the outside, how much are we losing? What's the impact on our profits going to be and can we restructure these costs some better way, maybe leasing rather than buying so somehow the costs would be shared regionally not just by my unit?

I didn't get right away what this was going to cost us. If we would have picked up on that as it happened we wouldn't have had that adverse effect on our P&L. Of course, no one else in my organization mentioned how it was going to impact the bottom line, but I can only blame myself for that really. I didn't know to ask the right questions.

Interviewer: What did you learn from this experience?

Tom: I really blame myself, even though the plant manager knows also that in the future he needs to address these issues a lot quicker. It was a learning experience for everybody involved. Now we put together a report where we look at variances that each plant runs monthly. And we do it regardless if it's positive or negative. So we'll pick up a mistake in the booking which we didn't do last year. Last year we said, “Well, it's a nice positive credit variance. Why worry about it?” And then also I've told my people that if we have a problem, they are expected to share that problem with me today, it's our problem. If you share it with me tomorrow, it's your problem. I think people understand that I'm willing to shoulder all of these mistakes, but only if we've discussed them up front right away. If you try to fix it and keep it to yourself, well then you sort it out yourself.

From this excerpt, some evidence of learning aptitude is evident in Tom. He describes the incident in detail, he is frank about his failure, and he can articulate how he set up systems to prevent similar incidents in the future. He also articulates how the incident had multifaceted implications. Not only did he personally lack the knowledge to make a well-informed decision, he needed to create an organizational culture that encouraged others to speak up and identify issues.

Assessing for learning aptitude feeds not only into the hiring and selection process, but into the development process after a person takes a new position. The new hires can be coached on how to use this information to build and reinforce their own propensity for learning.

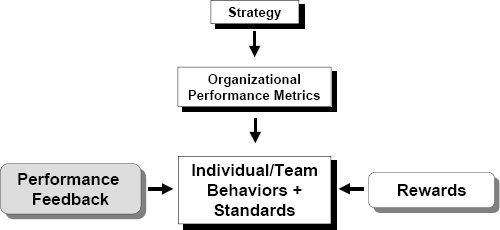

PERFORMANCE FEEDBACK

Performance feedback systems monitor performance and inform each person how well he or she is doing against expectations. Performance feedback is one aspect of a broader performance management system that includes goal setting, performance measurement, and performance appraisal. Organizations that truly believe that people provide competitive advantage know that they have to connect the strategic business imperatives to individual employee performance. As shown in Figure 6-7, performance metrics translate the strategy into required individual and team behaviors and standards. In Chapter Five we discussed how the organization's reward system can motivate and reinforce the right behaviors. Performance feedback is the final element in this equation. It lets people know how they are doing so that they can make corrections.

Traditional performance feedback systems depend upon yearly goal setting and performance-appraisal meetings between an employee and his or her manager. No matter how well constructed, traditional systems will have limitations. This is especially true if you have redesigned your organization to configure work around changing projects and processes, if you extensively utilize teams, and if you use managers as facilitators, advisers, and coaches rather than simply as supervisors of work. Traditional top-down systems depend largely on the view of one person—the boss. In a flexible and dynamic organization, the boss may have the least-informed view of an individual's performance for a number of reasons.

Figure 6-7. The link between strategy and performance feedback.

![]() Use of Teams. As work becomes more cross-functional, customer-oriented, and process-oriented, lateral rather than vertical relationships tend to define performance. The basic unit of work configuration becomes a team, requiring a high degree of interdependence among members to get the work done. If one person doesn't deliver, someone else has to pick up the slack. Although the quality of performance of individual team members will be apparent to the team, it may not always be apparent to a manager, who only sees the integrated output of the team.

Use of Teams. As work becomes more cross-functional, customer-oriented, and process-oriented, lateral rather than vertical relationships tend to define performance. The basic unit of work configuration becomes a team, requiring a high degree of interdependence among members to get the work done. If one person doesn't deliver, someone else has to pick up the slack. Although the quality of performance of individual team members will be apparent to the team, it may not always be apparent to a manager, who only sees the integrated output of the team.

![]() Increased Management Span of Attention. When organizations flatten and remove management layers, the span of management control and attention increases. Managers who oversee the work of people scattered among multiple locations have less opportunity to observe how the work is getting done.

Increased Management Span of Attention. When organizations flatten and remove management layers, the span of management control and attention increases. Managers who oversee the work of people scattered among multiple locations have less opportunity to observe how the work is getting done.

![]() Multiple Bosses. It is increasingly common for people to have more than one boss during the course of a year, because they either work on multiple project teams or are part of a matrix structure. Each of the project teams may have different leaders. In some cases, a peer in one situation may be a project leader in another. An employee may end up having limited direct contact with his or her formal manager.

Multiple Bosses. It is increasingly common for people to have more than one boss during the course of a year, because they either work on multiple project teams or are part of a matrix structure. Each of the project teams may have different leaders. In some cases, a peer in one situation may be a project leader in another. An employee may end up having limited direct contact with his or her formal manager.

![]() New Role for Management. Perhaps the largest trend driving the emergence of new performance management systems is the rethinking of the role of supervisors and managers in the organization. The traditional hierarchical pyramid implies that managers supervise and control the work of those below them in the hierarchy. In organizations that have successfully empowered and enabled their front-line workers, the manager becomes a facilitator and boundary manager who supports the workers, rather than the other way around. For example, such a manager might be focused on securing resources for the group, developing their skills, and helping them interact and resolve differences with other groups. In this scenario, having the group evaluate the manager can be more important than the manager's evaluation of the group.

New Role for Management. Perhaps the largest trend driving the emergence of new performance management systems is the rethinking of the role of supervisors and managers in the organization. The traditional hierarchical pyramid implies that managers supervise and control the work of those below them in the hierarchy. In organizations that have successfully empowered and enabled their front-line workers, the manager becomes a facilitator and boundary manager who supports the workers, rather than the other way around. For example, such a manager might be focused on securing resources for the group, developing their skills, and helping them interact and resolve differences with other groups. In this scenario, having the group evaluate the manager can be more important than the manager's evaluation of the group.

The increasingly broad range of performance indicators—not all of which are quantifiable with hard data—requires the use of new forms of performance feedback, particularly at the management level. As you design your organization, you may want to consider three types of performance feedback that can supplement your existing systems and provide multidirectional views of performance:

1. Peer and Team Evaluation: Peer appraisal gathers input from a person's colleagues who are at or about the same level. The peers work and interact together but may not share responsibility for outcomes. Team appraisal is essentially the same except that the peers are on a formal team and do have shared responsibility for their work products. In both these systems, input on performance is gathered from the peers of the person being evaluated on the assumption that colleagues have the best sense of how people approach their work, the results they achieve, and how well they work with others. If the organization is completely team-based, the majority of performance feedback may take this form. In other organizations, input from peers and team members may supplement a traditional supervisor-oriented appraisal. Peer and team evaluation systems reinforce the organizational message that collaboration and integration are important. Introducing peer and team evaluation systems, however, presents some challenges:

Getting honest feedback. Peers may be less than eager to play the role of judge. Even when kept completely confidential, peers tend to rate each other highly. People don't want to undermine positive working relationships or hurt other people's promotion or pay opportunities, possibly in the hope that others will do the same for them.

Individual performance not always adding up to team performance. Peer appraisal provides valuable insights into individual performance, but may not reflect the complex group dynamics that influence how well the team as a whole performs.

Linking feedback to rewards. If compensation and reward systems are built around performance measures, than peer and team feedback can be designed to serve as a source of input for these decisions. Linking feedback to rewards will certainly heighten the attention and interest given to the feedback process. On the other hand, people tend to be more honest and critical if they know that the results will only be used for developmental purposes.

2. Cross-Evaluation. In a cross-evaluation system, an individual receives feedback from others in a position to assess job performance strictly as it relates to meeting customer needs. Whereas peer and team evaluation systems tend to collect feedback from people who reside in the same business unit, cross-evaluation systems are often composed of people in different parts of the larger organization. Cross-evaluation differs from peer evaluation in that peer evaluation focuses on teamwork whereas cross-evaluation deals with business results and is linked to customer indicators. Typically, participants come from functions that are highly dependent on one another for accomplishing a process or producing a customer deliverable. Feedback is focused on how an individual's job skills and behavior impact the ability of others to perform.

For example, in a functional organization a cross-evaluation system could be used to assess the new business development process. Participants might include members from sales, marketing, strategic planning, and product development. Each person would identify the relevant standards of performance (timeliness, quality, etc.) needed from each other person in order for them to collectively produce a successful customer bid. The work you did to identify role interdependencies in Chapter Three can be helpful in determining mutual expectations in a cross-evaluation system.

Cross-evaluation is a powerful way to promote collaboration between business units and functions. The ongoing communication built by the cross-evaluation process is as important an outcome as the actual ratings themselves. Cross-evaluation systems are particularly useful in strengthening horizontal links in a matrixed environment. Setting up a process whereby a group of individuals with common goals provide each other with periodic feedback builds a safe environment for people to share information and ideas and to begin collaborating through a legitimized, business-focused mechanism.

The focus on business results is critical. Many senior executives, who have the most to benefit from tools that help them negotiate complex matrix systems, are resistant to spending time on activities that seem soft and not directly linked to business results. While the design of such systems presents the same challenges as peer and team evaluation systems, cross-evaluation is focused more on a particular process or customer outcome and the standards are determined up front, thereby making it easier to identify and collect honest and critical feedback.2 Performance feedback used in this way helps the organization build lateral capability by linking parts of the organization that may not be grouped together in the vertical structure.

3. Upward and 360° Feedback. Upward feedback tells managers how they are perceived by people in the work groups they manage, and 360° feedback adds in peer, boss, customer, or other perspectives. Organizations that emphasize the importance of learning and development find that upward feedback is one of the best tools for making managers aware of the gap between how well they believe they manage their people and what they actually do in day-to-day practice. Many managers believe that they delegate effectively, that they coach and support their people, and that they give frequent feedback—when in fact they don't. The fact that data is gathered confidentially allows subordinates to express observations about their managers more honestly than they would feel comfortable doing face-to-face. If this awareness is backed up by a plan for development, then upward and 360° feedback can be an effective way for building the organization's management capabilities.

FROM TRAINING TO LEARNING

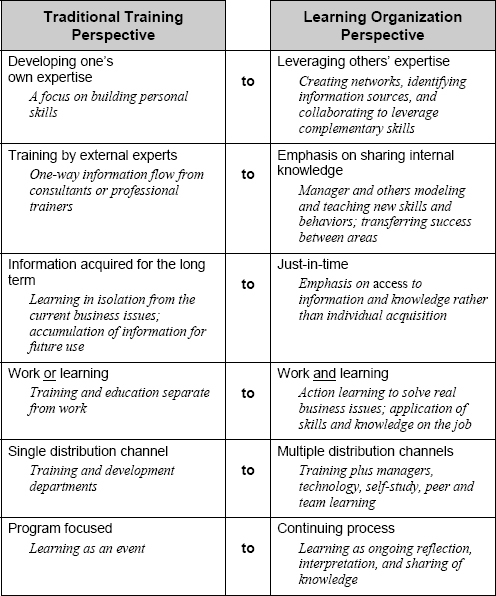

If the organization redesign is in response to a fundamental change in direction, employees at all levels will have to “retool” their skill sets. One of the most significant trends in the 1990s has been the effort by many companies to transform themselves into “learning organizations.” It began with Peter Senge's belief that organizations that learn by tapping into individual and team potential and through systems thinking will have a competitive advantage.3 Just as an individual's learning aptitude can contribute to success in a dynamic world that requires capacity to deal with unanticipated problems and opportunities, building learning capability into the organization should provide similar benefits.

As a result of this thinking, many organizations have reconceptualized their training functions. These companies have transformed departments that had focused solely on delivering skill-based courses into “learning and development” functions closely tied to broader organizational development activities. Figure 6-8 summarizes the changes organizations that focus on learning have been making. The new employment contract also means a new learning contract. In exchange for providing the opportunity and support for skill development and rewards for learning, employers expect employees to invest in their own development and help build the competence of others in the organization.

A paradox is that as organizations have put a greater emphasis on learning, there are fewer opportunities to attend traditional programs. In many businesses, the pressure to meet short-term performance targets and lean staffing mean that employees may never get around to attending elective and sometimes even so-called required training programs. It is important to leverage other activities for their learning potential. Many of the network-building practices we discussed in Chapter Four also support learning, such as job rotation and communities of practice. Technology is being widely used to enable distance learning and self-instruction.

SUMMARY

In this chapter we have looked at the final point of the star model, People Practices, to identify what types of HR systems can contribute to a reconfigurable organization. The chapter used the case example of AgroLife HR to illustrate a process for placing people into the new organizational structure. It also highlighted three pivotal practices that support the selection, performance, and development of the right talent for the organization. These practices begin with selecting people who have the aptitude to embrace and apply learning gained from new experiences and challenges. They include providing feedback from multiple sources to reflect the importance of peer interactions and the changing role of managers. Finally, broadening the concept of training to encompass learning and development is another practice that sustains the organization's ability to respond to change.

Figure 6-8. From training to learning.

This chapter leads into the final chapter of this book—Implementation—which focuses on managing the transition from design to reality.

NOTES

1. See also E. V. Velsor and V. A. Guthrie, “Enhancing the Ability to Learn From Experience” in Handbook of Leadership Development, C. McCauley, R. S. Moxley, and E. V. Velsor, ed. (San Francisco and Greensboro: Jossey-Bass and Center for Creative Leadership, 1998).

2. For a fuller discussion of the challenges of peer feedback and cross-evaluation see M. A. Pieperl, “Getting 360 Feedback Right,” Harvard Business Review, January 2001, pp. 142–147.

3. P. M. Senge, The Fifth Discipline: The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization (New York: Doubleday, 1990).

Tool 6-1. Staffing the new organization.

| Purpose: | Use this tool as a checklist when planning your own staffing process. |

| This tool is for: | Executive Team. |

| Staffing Process Checklist | ||

| Notes | ||

| Senior positions are filled first. |

|

|

| The process for staffing is communicated to the organization as soon as possible to minimize rumors and anxiety. |

|

|

| New roles, expectations, and standards are clearly defined and communicated. |

|

|

| The process is transparent and mirrors the organization's values. |

|

|

| The sources of data (interviews, performance appraisal, self-assessment, etc.) and the weight assigned to each are identified and agreed upon by the executive team. |

|

|

| The executive team has established clear criteria for decision making. |

|

|

| The process includes assessment for learning aptitude. |

|

|

| Placements are made based on individual capability and potential for learning, and to create groups and teams with complementary skills. |

|

|

| Development plans are created for all people placed or hired into new roles. |

|

|