Managing the Dynamics of Brand Performance

Main Themes

- Most of the metrics managers currently employ to track and manage brand performance are inadequate.

- The brand and business system is dynamic, with leverage for each choice segment constantly shifting. Moreover, there is a natural tendency for resources in the system to decay. As a result, investments must be made merely to sustain the status quo; you have to run just to stand still.

- To leverage underutilized resources and allocate brand-building investments effectively, managers must apply accurate and detailed performance intelligence. This will allow them to make informed decisions and target initiatives at key leverage points in the system.

- Understanding the performance of a business is not just about grasping the factual metrics of the brand architecture but also about establishing the prerequisites for successful branding and responding to consumer values as they evolve over time.

- The brand management debate must be refocused. Classic marketing discussions based on past brand performance and consumer awareness levels get companies nowhere. Instead, they need to adopt a holistic view of the integrated brand and business system. This should allow them to answer a number of tough management questions. It will also reveal that there are far more opportunities for management to take initiatives to optimize performance than most businesses recognize.

Applying a holistic and systemic approach to brand management will help managers develop more robust strategy, make investments in the right initiatives, and align the organization to compete more effectively for stakeholder choices.

Since the value of a business lies in the whole system, companies need to be effective at building and leveraging all the resources in the system to optimize value creation. For too long, managers have focused primarily on tangible resources simply because they are easily quantifiable and often appear in management reporting. In the process, they have largely neglected other resources, such as the number of convinced consumers, the state of staff morale, and other “soft” or knowledge-based assets such as patents and skills. Starved of management attention, such resources are underutilized in many companies.

To establish a solid foundation for brand growth, managers need to start by understanding what the brand is about, where it can be taken, and what market and consumer opportunities exist (see text panel “What Are Brands?”).

This chapter focuses on three areas central to brand and business performance comprehension and management:

- The prerequisites for successful branding: articulating the key strategic choices to be made to earn stakeholder choice. The perspective on growth must be market-driven and “outside in” (where and how can we source what growth?) rather than “inside out” (setting year-on-year growth targets irrespective of brand resources).

- The brand architecture: mapping, quantifying, and understanding both the system and the leverage opportunities within it. Intangible resources are integral to this process; they can make all the difference to competitive performance.

- Values systems: aligning brand and stakeholder values to ensure value creation.

The CEO must understand and integrate all three in order to develop and implement a robust brand growth strategy.

The Prerequisites for Successful Branding

A company cannot set out to brand simply because it wants to. Stakeholders’ choice of a brand has to be earned, just as politicians have to win elections before they can hold office. But elections happen only every few years, whereas a company must earn its customers’ choices day in, day out.

There are four interdependent prerequisites for successful branding, each of which implies a series of strategic choices for management:

- Establish a clear strategic principle. Management must clearly articulate the mission, vision, and values of the company and brand, and embed them in the organization so as to align and focus every person within it on competing for choice. It must clarify why it wants to brand and define its target markets and segments in the light of the changing environment.

- Provide a distinctive value proposition. The company must develop and consistently deliver a value proposition that is distinctive, attractive, and relevant to the intended segment so as to earn customers’ choices, secure repeat purchases, and justify the price premium.

- Control core resources in the value chain. The company must develop and leverage the resources (ideally proprietary ones) that it needs to deliver the value proposition. These resources often include aspects of systems, skills, structures, and intellectual property that are applied to build and leverage unique competitive advantage and to prevent or inhibit the copying of products or practices by rival players.

- Proactively manage stakeholder relationships. The company must engage in real two-way relationships that enable it to communicate effectively and to capture learning in order to enhance its value proposition.

Exhibit 4.1 shows how these four elements interrelate to inform and develop one another so that a company can earn choice on a continuous basis. This dynamic process fosters innovation and drives business renewal.

Exhibit 4.1. The Dynamics of Earning Choice

The benefits provided by a proposition often have to do with resolving a real or perceived customer problem or need on the one hand, or providing or inducing an experience that is perceived as positive by the customer on the other. The extent to which these benefits are delivered is important to future repurchases and positive word of mouth, but there is a delicate balance to be struck. Overdelivering may generate repurchases, but it can equally undermine margins. The secret is to satisfy the specific expectations of relevant customer segments—in other words, to make the right fact-based strategic choices.

Progressive Corporation, a U.S. vehicle insurance specialist, has a well-defined and distinctive value proposition offering a range of nonstandard policies for high-risk applicants. It focuses on providing insurance to people who own motorcycles or have been charged with drunken driving and who cannot usually obtain coverage from other insurers at any price.

Whereas its competitors group all potential applicants with similar profiles into the same risk pool, Progressive conducted a careful analysis of applicants’ behavior, drew on its 30-year database of high-risk drivers, and identified behavior patterns that distinguish genuinely high-risk applicants from relatively low-risk ones. By concentrating on these relatively low-risk drivers, who would still have been classified as high risk and refused insurance by other insurers, Progressive was able to target a niche market of its own and develop a successful high-margin business. The company uses a complex rating system to provide insurance policies that better match applicants’ profiles and is able to command a price premium of up to 300% over the standard rate.

Since no business can be all things to all people, management must make strategic and tactical choices about how and where it wants to compete for which stakeholder choices. Exhibit 4.2 shows how the imperatives for successful branding translate into a series of detailed management choices.

The Brand Architecture

Just as builders work from architects’ drawings, managers, as brand builders, should work from a brand architecture that shows how the basic building blocks—resources—fit together. Armed with a clear brand blueprint, managers will share a better understanding of their business, make better decisions about the allocation of resources, find it easier to reach consensus, and achieve better results. The blueprint will allow them to quantify the implications of the choices they make and identify the specific levers that will help them accomplish their objectives.

Exhibit 4.3 illustrates a simplified blueprint for a retail brand, showing how tangible, intangible, internal, and external resources interact within the overall system. The curved arrows show that resources (such as salespeople) or management levers (such as retail promotions) can influence the flow rate of other resources (such as retail distribution).

Exhibit 4.2. Making Strategic Choices

Arguably, managing stakeholders—free agents who make up their own minds—is more complex than managing inanimate resources such as equipment or capital. Although competing for stakeholder choice may make good sense to them intuitively, most managers shy away from it, losing heart when asked to manage something that is complex, incorporates many intangible components, and cannot be kicked.

What does the absence of a clear brand architecture mean for a business? When structures, facts, and a holistic perspective on stakeholder choice are lacking, managerial activity inevitably evolves in a fragmented manner around subcomponents or functional areas. The typical result is a series of isolated and disconnected initiatives such as customer relationship management, loyalty-based management, process reengineering, or knowledge management—each worthy enough in the right context, but capable of generating more work and confusion than benefit if used without regard for the system as a whole.

Exhibit 4.3. Interactions in the Brand System

Whether any particular initiative can be applied successfully will depend on the status of the resource system: for example, how mature a brand is in a given market, which reflects the number of people residing at the later stages in the choice chain. Once managers have developed a clear brand architecture and quantified its hard and soft resources, they can understand how a given initiative is likely to influence performance, and to what extent, and so make informed choices about how best to allocate their investments.

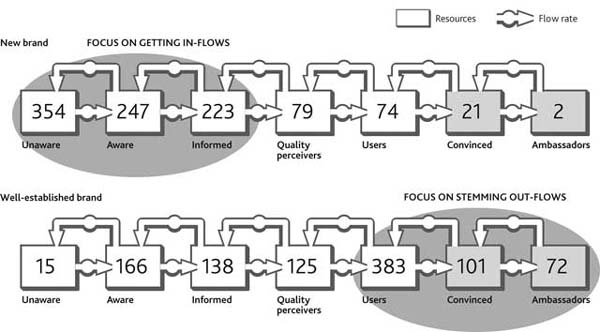

Exhibit 4.4 illustrates this idea in a simplified form by contrasting two customer choice chains. The chain for a new brand shows that management needs to focus on generating inflows in the early stages of the chain. With a well-established brand, in contrast, the focus should be on stemming outflows in the later stages.

Exhibit 4.4. Identifying Where to Focus

Experience tells us that a clear understanding of stakeholder choice chains provides the only robust platform for developing and executing strategy. Once managers are equipped with a visual plan of how the brand system works, they can have informed debates about the initiatives they might pursue and the results they can expect. The brand architecture acts as a shared language for managers from different divisions and countries, and as a basis for evaluating brand performance.

There are two caveats to bear in mind, however. First, each brand’s architecture is unique. It follows that management initiatives that have worked for one brand are unlikely to work in the same way when applied to another. Copying best practice just does not work. The only valid basis for evaluating initiatives and making decisions is to be found within an individual brand’s resource system. Any action that a company takes has to be judged in terms of the impact it will have on that system.

Second, the brand architecture is only a snapshot of the state of resources at a given moment in time. In reality, the resource system is in a constant state of flux, with constant inflows and outflows along the choice chains. People move along the chain as they become “convinced”—especially if management applies the right levers—but there is also a natural tendency for consumers to flow back along the chain: for example, from “convinced” to “users.” To counteract this tendency, even the best-known consumer brands have to keep up their marketing and promotional activities. If Coca-Cola stopped advertising (unthinkable though that might seem), its huge reservoirs of “convinced” consumers would gradually deplete.

Three essential components go to make up the brand architecture:

- The brand resources: the tangible, intangible, animate, and inanimate

- The interdependencies between resources: the inflows and outflows that influence the state or level of the resources

- The flow drivers: the two types of factors that influence flowrates—the levers controlled by management and the external factors over which it has little or no influence

Brand Resources

Just as an architectural drawing needs a scale, a brand architecture needs to be populated with data. Most companies have abundant intelligence about their markets and customers. The trouble is, it frequently does not match up with the brand architecture. It is not resource based, and it may lack crucial data such as the number of customers residing at a particular stage in the choice chain or the flow rates between different stages.

Managers need to measure resource flows before they can assess the scope of problems and opportunities for their brand. Imagine that my rate of new customers won is declining relative to my rate of customers lost. When will I see a net reduction in the customer base? I cannot answer the question without knowing both flow rates.

It is not just the levels and flows of existing customers that need monitoring; tomorrow’s customers are important too. For luxury brands, for example, the level of “virtual convinced” consumers and the rates of inflows and outflows of this resource are as critical as the movements of current purchasers.

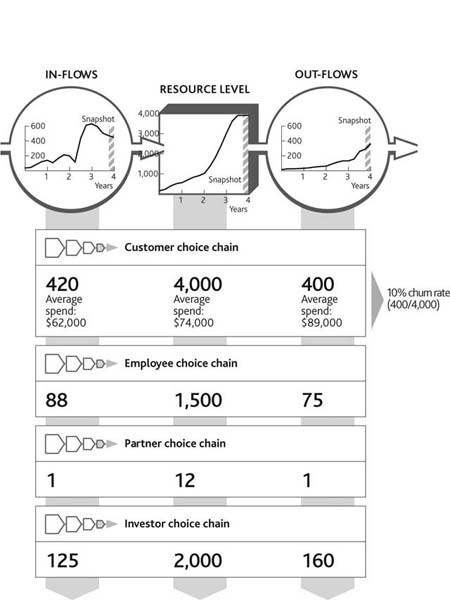

Putting numbers and values against resources, especially potential and convinced customers and their associated flows, is the only way to establish appropriate performance metrics and get an accurate picture of your brand’s health. In the example illustrated in Exhibit 4.5, customer inflows are declining while customer outflows are rising. At the time of the “snapshot,” customer inflows are still higher than outflows (420 new customers versus 400 lost customers this month), but the total number of customers is starting to level off as the two flows get closer to canceling each other out.

The impact of these flows can be seen in the investor choice chain. Although 125 new investors joined this month, 160 left. Investors are losing confidence in the brand as its performance deteriorates and customers defect.

This example demonstrates the importance of measuring both levels and flows by stakeholder and segment. Indeed, this should be standard practice in any management reporting since the flow rates are lead indicators for the resource levels.

In the case of a U.S. personal care brand, monitoring consumer flow rates allowed the brand owner to evaluate opportunities for value creation (Exhibit 4.6). Analysis of the data revealed that the brand had a churn rate (customers switching to a competing brand) of 10% of the customer base per year. The company carried out a benchmarking exercise with competing brands in the same price range and discovered that the best-in-class churn rate was 8%. It worked out how much additional value it could create by reducing churn to the best-in-class level. Finally, it weighed up the incremental sales over a given period against the costs of implementing targeted measures to reduce churn and used the results to reach a sound fact-based decision on the right corrective actions to take.

Exhibit 4.5. Monitoring Brand Health

Although this example is simplified—in reality the company would need to take into account the effects of churn-reduction measures on the rest of the brand system—it serves to illustrate how an analysis of brand resource flows can be used to support and inform management decision making.

Exhibit 4.6. The Impact of Reduce Churn

Interdependencies Between Resources

Stakeholder resources are not stable; there is a continuous loss rate over time. Just as houses fall apart without maintenance, choice chains are subject to gradual decay. As a result, brands have to invest in keeping their inflows going simply in order to maintain the status quo; they have to run just to stand still.

If a company wants to grow its customer base, it must do one of two things: boost inflows so that it wins new customers at a faster rate than it loses old ones, or reduce outflows so that it loses customers at a slower rate than it acquires new ones. Either way, customers accumulate and the customer base increases.

But things are not quite as simple as this may suggest. Management must weigh a series of issues. At what point do we step in to try and improve the flow rate to grow (customer acquisition initiatives) or to stem the decline (customer retention initiatives)? How do we determine which initiatives will influence which flow rates and by how much? What is the right level of investment in each of these initiatives?

Breaking down the decisions in this way can yield new insights into questions that many companies grapple with: How much should we spend on marketing? Are we achieving the best possible return on our investments? However, it is important to recognize that marketing is just one of the levers that can be used to grow or retain customers’ choice. Through diligent analysis, managers can ascertain what contribution marketing—as opposed to new product development, service levels, distribution, and so on—makes to the various flow rates in the customer choice chain and thus determine how much investment is required to maintain the system in a steady state, all things being equal.

Within a resource system, as we have seen, there are inflows (which lead to growth) and outflows (which lead to entropy). There is also a third type of flow: migration (Exhibit 4.7). Migration takes place when a resource moves from one choice chain to another.

Migrations typically take place in one of two settings:

- When a company seeks growth in new markets or sectors. If a company wants to establish a presence in a new market where it currently has neither structures nor recognition, it will often move skilled and experienced people from an existing resource system into a new one.

- When a company is trying to consolidate its business and move its customers from one brand to another. Such brand consolidation often happens in cases where two companies merge and decide to streamline their brand portfolio. Rather than abruptly discontinuing a brand, the merged entity will probably want to migrate its users across to a comparable brand that it will continue to support. Making such transitions without diluting the existing resource base or jeopardizing the effective working of the current brand system can often be tricky.

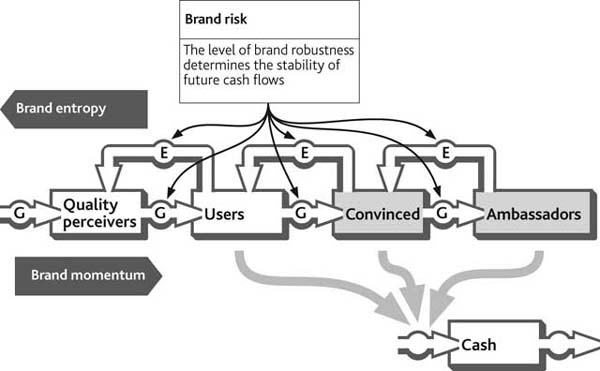

Most brand owners and investors are quite rightly preoccupied with managing and mitigating the risks associated with the brand. As ever, understanding resource flows is the best place to start if you are assessing the robustness of your brand architecture and the performance of the system as a whole. Since revenues derive from the number of customers paying a particular price for a brand, it is the volatility of these resources that determines the risk associated with future cash flow. So it is important to gauge, for example, how quickly “convinced” customers might defect following an unexpected mishap or market discontinuity.

Exhibit 4.7. Growth, Entropy, and Migration

In theory, if there were no flows in or out of the customer resource or other changes in behavior, there would be no risk associated with the brand. In practice, brand risk is a function of the stability of the resources in the customer choice chain (Exhibit 4.8). It follows that the application of management levers influences not only brand earnings but also brand risk.

Brand earnings (cash inflow) are a function of the number of customers and the amount they spend on a brand. Brand risk reflects the volatility of this cash flow, which is determined by the outflow of customers. A high customer outflow would indicate a high level of uncertainty regarding future cash flows, and hence high brand risk. Conversely, a company with a large number of loyal customers and low customer outflow would enjoy high earnings, a stable cash flow, and low risk.

Exhibit 4.8. Assessing Brand Risk

In 1999, people in Belgium and France complained they felt ill after consuming soft drinks manufactured by Coca-Cola. Although the company took a while to come to grips with the problem, most consumers, rather than becoming “refusers,” quickly resumed consumption once the problem was fixed—a clear sign of the brand’s robustness. Other stakeholder chains operate in much the same way. For example, investors are more likely to stay with a company for the long haul if it enjoys the confidence of other stakeholders, as Warren Buffet attests.

Management Levers

Actions taken to influence a brand system will produce a reaction at some point within it. Even if no actions are taken, initiatives pursued by competitors or changes elsewhere in the environment will cause reactions in the system and thus affect performance.

In short, the brand system is dynamic, and understanding its dynamics is essential to managing performance over time. Several consequences follow from this:

- Actions taken today may have immediate and long-term impact.

- Actions taken today will produce a different outcome from the same actions taken in the past or the future.

- The same actions taken in different markets will produce different outcomes.

- The same actions taken at the same time for different brands will produce different outcomes, even within the same product category.

- Doing nothing will influence performance too.

The case of U.S. telecom hosting company Exodus Communications demonstrates the importance of staying alert to the dynamics of the market and the choice chain. In the 1990s, the company’s management developed a vision of establishing a leading role in the market by building on existing competencies and taking advantage of business opportunities arising from the advent of the Internet era. By mid-2000, Exodus had realized its ambition. Yet just a year later, it filed for bankruptcy. What went wrong?

In an emerging market, there are few customers using a service but a large pool of potential customers. Over time, as people sign up to one provider or another, the resource of potential customers depletes. At a certain stage, the net value of adding incremental new customers falls below the value of retaining existing customers. Exodus’s management failed to recognize this crucial “inflection point” when its priority should have shifted from acquiring customers to retaining them. As a result, it continued to devote time and resources to growth initiatives when it should have been paying attention to stemming customer losses.

If you look at the choice chain diagram in Exhibit 4.9, you can see that different management levers and influencing factors affect the flows at different stages. The levers required to move people along the choice chain are not all related to marketing. Far from it: Marketing is just one weapon in a company’s armory to promote customer choice. Other important levers can be applied to influence product quality, service, skills, staff numbers, and innovation.

For personal care company Gillette, a strategy of continuous innovation is central to earning customer choice. The company has recognized that if it fails to innovate, competitors will catch up and start to compete for its customers. To stay ahead of the game, it launches new products or variants at frequent intervals. These products are often based on advanced technologies that will take rival companies years to copy, thus affording Gillette a window of competitive advantage.

Careful analysis of the customer choice chain will reveal where the greatest opportunities lie for improving any flow rate and what the relevant actions are likely to cost. A detailed understanding of critical levers will allow management to assess whether the resources it is allocating to marketing and other areas are having the desired effect. It also enables a company to look beyond marketing and see whether every activity in its strategic and operational agenda is aligned with the need to compete for choice.

Exhibit 4.10 illustrates how the leverage in one company’s choice chain varies at different stages and for different consumer segments. As we saw in the Exodus case, leverage also varies over time as stocks accumulate and deplete. Therefore, companies need to conduct leverage analyses on a regular basis.

One further benefit of a clearly defined brand architecture is its suitability for scenario simulation modeling. It can easily be converted into a computerized resource model and then populated with data to create an immensely valuable tool. Managers can use it to test different strategies and analyze their outcomes over time in a risk-free environment. Such models work in a similar way to the flight simulators used in pilot training.

Exhibit 4.9. Management Levers and Influencing Factors

Exhibit 4.10. Quantifying Leverage

Aligning Value Systems

Intimately linked to both a company’s strategic principle and its ability to generate consumer choice is its value system. From a branding point of view, three value systems are central (Exhibit 4.11):

- Corporate values. These constitute the identity of a business and are often articulated in its strategic principle. They determine and constrain the way a company thinks about its proposition, its brand, and its market. Corporate values are those to which a company adheres in conducting its business and defining its role in society.

- Brand values. A company will engineer a set of brand values (and thus the brand image) on the basis of its corporate values (identity). So, starting from a particular set of values, one company may fashion one brand image while another company comes up with an altogether different image, even though both brands are intended for the same customer segments. Companies seek to communicate their brand values in such a way as to maximize “values fit”: a match with the values of target consumers that will earn their price acceptance and thus their choice.

- Consumer values. These are the guiding principles, beliefs, or mental models to which people adhere in interacting with others and leading their lives. An individual’s value system influences his or her aspirations and actions, evolves slowly over time, and often varies by continent and country. Most of us live by a number of values that together make up our value system. Research shows that people tend to seek out others with similar values. Equally, they embrace concepts, ideas, or brands that closely match their own values.

Exhibit 4.11. Core Value Systems

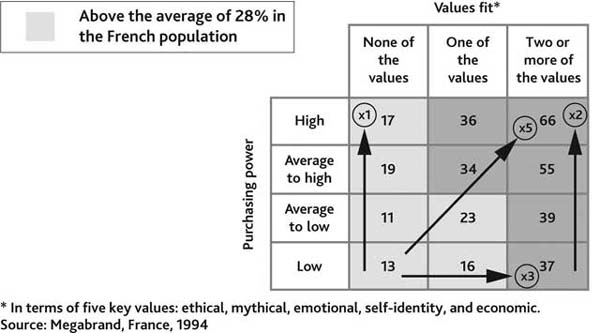

If we look at the factors that drive consumer choice and the acceptance of a price premium, research shows that the values fit between brand and consumer is considerably more important than consumer purchasing power (research conducted by Megabrand in France in 1994). In other words, consumers are more willing to pay a price premium when there is a high degree of values fit.

This holds true for all consumers in all economic categories. Exhibit 4.12 shows that in the absence of values fit, few people—whether their purchasing power is high or low—are willing to pay a premium. However, people with low purchasing power are almost three times more willing to pay a premium if they perceive a high degree of values fit.

As society changes, so do consumer values. Companies that fail to monitor and respond to these changes can easily go off the rails and lose customers’ continuing choice.

Consider UK mass-market retailer Marks & Spencer. Once a market leader with a solid reputation for quality and value, it lost sight of how its customers’ needs and wants were changing. Although operating profits grew strongly from 1995 to 1998, its reputation for quality had started to decline as early as 1991. This change in perception should have been an important lead indicator for the company’s management. Loyal customers finally lost patience with being short-changed, and revenues and profits tumbled in 1999, shocking investors, analysts, and journalists alike.

Exhibit 4.12. Values Fit and the Brand Premium

By January 2001, Marks & Spencer had earned the dubious distinction of becoming the company that had destroyed the most shareholder value in the previous 3 years; no other company in the Financial Times Stock Exchange (FTSE) 350 had subjected its investors to such a sharp decline in returns. It has taken 2½ years of hard work and renewed focus on the customer for Marks & Spencer to begin to regain some of its former luster.

Or consider Levi Strauss’s fortunes in the 1990s. Here was a brand that had carved out a global position for itself and was now exploiting advanced technology to offer customers jeans that were custom-fitted to their individual measurements. But as so often happens, the seeds of downfall were being sown even as the company’s growth appeared unstoppable.

Sure enough, Levi’s was innovating—but it was not the right sort of innovation. It was technology led, not market led. The company did not try to match the renewal of its product lines to emerging fashion trends. The result: Levi’s market share in men’s jeans plummeted from a high of 48% in 1990 to 25% in 1998. It has since recouped much of this loss by rethinking its approach to innovation and customer segmentation and introducing new lines such as its Engineered Jeans.

Understanding values is crucial to competing for choice. The fit or mismatch between the values projected by a brand and the values of individual stakeholders will determine whether the brand earns choice and justifies its price premium, or generates refusal.

Now let us consider an example of good values fit. Such is the enthusiasm for Harley-Davidson motorcycles that the Harley Owners’ Club is the largest of its kind in the world, with some 660,000 members. The company has come a long way from the 1960s, when it almost ceased trading after the Japanese launched a new wave of cheaper, better-quality bikes in the U.S. market. Harley-Davidson’s resurgence has made it the strongest motorcycle brand in the country and possibly the best known in the world.

But the company is still facing a big challenge: how to attract younger consumers without alienating its main customer base—the baby-boomers who make up more than half of its market. One-fifth are older than 55; only about 17% are 35 or younger. To tackle the problem, the company has begun to introduce new models such as the V-Rod, its first completely new bike in 50 years, which is similar to the more technically oriented racing bikes made by such competitors as Honda and Yamaha.

Harley-Davidson has also set up a motorcycling safety course to target new consumers. As an executive said in an interview,

We obviously recognize that the baby-boomer generation is getting older, but we think there’s still a long road to go with that group. We expect the V-Rod will bring in new, younger customers as well as appeal to our existing base. (Thornton, 2001)

As with other resources in a choice chain, values accumulate or deplete over time, and need to be reinforced. With its new launch, Harley-Davidson is building relevant new values such as modernity and hedonism, while reinforcing existing values such as vitality and freedom. This case serves to illustrate how companies can track the different values of different age groups and respond with new products that allow younger generations to establish a values fit with their brands.

* * *

In the not too far distant future, performance comprehension will be informed by metrics that are not commonly discussed in management debates today. The main differences will be the monitoring of key resource flows and levels in a broader systemic context, a much higher level of detail, and the inclusion of many intangible components that are not currently measured. Taking steps to establish such comprehensive structures and capabilities sooner rather than later is likely to provide early movers with competitive advantages. We go on to look at some of these steps in the final chapter.