Webonomics, or the Forces That DetermineHow We Buy

In 1996, Schwartz, a technology writer and former editor of Business-Week, coined the term Webonomics: “the study of the production, distribution, and consumption of goods, services, and ideas over the World Wide Web” (Schwartz 1997). Back then, the Internet was “astonishingly inhabited by tens of millions” of users around the world, and we used charming phrases like “World Wide Web” when talking about the new revolution slowly emerging around us. From his prescient vantage point at the beginning of the Internet, Schwartz foretold nine principles that would be critical to business success in the new economic arena. Of the tenets he defined, his recognition that the resource of scarcity in the new economy would be the “ability to command and sustain that attention” was the most prophetic. That he never imagined more than tens of millions of users ever engaging in this economy makes his observation that much more visionary.

Fast forward to today: 4.66 billion active daily users; 100 percent penetration in the under 29-year-old category; even your grandmother has 4.6 social media accounts. The “attention economy” has its own Wikipedia page, and tens of millions of people have watched TED talks on this topic alone. The battle that is being fought every minute of every day in this digital arena is the desire to be seen and loved by the millions of eyeballs walking past each website on Internet Street (Lecinski 2011). And the consumers are winning the fight.

Consumers are in the driver’s seat, deciding at scale what the destiny of each brand will be. They are in the process of turning business to consumer (B2C) commerce into consumer to business (C2B). We simply have not noticed the full extent of it yet. Consumers have access to all the information inside their phones. They have adapted and become more sophisticated, easily thwarting sellers’ efforts with tabs closed and forgotten at impressive speeds. In the United States, the average citizen is exposed to upwards of 4,000 brands each day. Think about that—4,000 sellers vying for you to choose them from the moment you open your eyes.

Consumers have become experts at ignoring long-standing methods of being sold to. In 2020, 47 percent of consumers were using adblockers, costing U.S. businesses $12.12 billion in lost revenue. In 2021, Apple announced that they would turn off tracking cookies, small data files used to identify site visitors, at the operating system level. The significance of this decision is enormous, as cookies are one of the primary techniques that companies such as Facebook use to follow individuals’ online habits when they click around on the Web. Cookies are the reason you keep seeing ads for black turtlenecks, interior design tips and new jobs on every website you visit.

The data stored in the cookies helps advertisers target specific audiences, an activity they pay a premium for. Turning off cookies by default or giving users greater agency over whether they accept cookies or not, has the potential to wipe out significant advertising revenue for companies like Facebook—and significantly change the strategies that sellers can rely on to become seen.

Conning the customer won’t work. The whole language of branding dissolves in the new media. The logic behind brand differentiation disappears. The new generation of consumers are more sophisticated. Consumers see right through what advertisers are manipulating them into doing. Most people in advertising don’t understand that. Advertisers have been getting away with murder.

—Evan Schwartz, Webonomics (1997)

To succeed in business today, it is not enough to provide an outstanding experience. It is not enough to have a cracking marketing team that shepherds significant quantities of site visitors to your website on the promise of 2.35 percent conversion rates. It is not enough to provide efficient transactional encounters, even if you do know the customer’s name and basic demographics. To succeed today and well into tomorrow, you need to create conditions that will foster lasting relationships with your customers in a digital space. This book will show you exactly how to do that in Part II. In this section, we look at the building blocks of lasting buyer brand relationships—the timeless forces that influence how we buy, how we make decisions, and how we form relationships.

The Future Is Not Random

It’s easy to get confused when thinking about the future. It is a time that has not happened yet, and so, we mistakenly believe, is unpredictable. We forget that the future is a consequence of what is here today, and what is here today is known to us already. In The Imagination Challenge, Alexander Manu posits that we can make a reasonable prediction about tomorrow by examining the knowns of today (Manu 2007). The strategy described in the book, used by Manu to de-risk the future state for Fortune 500 companies like Disney, LEGO, and Motorola, is based on the idea of looking at “signals.” Some of these signals are fast-moving, such as emerging technologies, while other signals are slow-moving, such as human behaviors. If we understand the mechanics of the slow-moving signals, the ones that impact how we make buying decisions and form relationships, we can not only optimize the digital brand space for today but have confidence that foundational parts will continue to be relevant and effective into the future.

Brand Monogamy, Temporary Fling, or Polyamorous Free for All

Every generation has its own characteristics, shaped by its exposure to world events, trends, technologies, and even diseases. The way we experience life affects our core values, and with that, shapes our attitudes toward how we buy, what elements of the purchase we prioritize, and what or whom we are loyal to (Ordun 2015). Our grandparents were likely loyal to a brand for life: once you chose Tide, you stayed with Tide. You probably have a different set of criteria for choosing washing powder, and ultimately, all the brands you choose to spend your dollars with.

Brand loyalty is the degree to which we exhibit a bias toward choosing a specific brand over alternate brands over time (Jacoby and Kyner 1973). Brand loyalty is, in essence, a commitment between yourself and a brand and is characterized by three components:

1. Satisfaction

2. Relationship

3. Time

It makes perfect sense that we exchange our loyalty, in essence giving up our future freedom to evaluate options when making a choice, only if we have a positive relationship with a brand over time. For example, you may discover a particularly stylish and flattering brand of black turtleneck that you purchase. The said black turtleneck performs well, and you are satisfied with the look, feel, price and style. You wear the turtleneck and get a few compliments from your friends. Next time you need to buy a garment to wear in public, you look around at other options and maybe even buy a black turtleneck from another brand. When the new turtleneck arrives, you will compare it against the original brand you were happy with. The next time you need to buy a black turtleneck, you save yourself some time and order 10 from the first brand that you loved. In the future, whenever a turtleneck needs to be replaced, you return to the brand you are now loyal to. Your effectiveness as a seller of turtlenecks depends entirely on whether you understand what keeps your loyal fans committed to you.

Of the three components of brand loyalty, satisfaction is the only factor you can directly affect as a seller. The relationship that is formed over time with your brand is not within your control. It is the subjective experience that evolves and is experienced by your buyer over the course of engaging with you. Each engagement, however, is evaluated by the buyer through a measure of satisfaction. Although satisfaction is also subjective, it is a function of the expectations held going into the interaction—and expectations can be managed (Figure 1.1).

The quality of an experience is measured as the difference between our perceptions and our expectations of an experience (Harrison 2015). This is the critical part—as a seller, you have zero control over the perceived experience of a buyer. However, you have a substantial amount of influence over their expected experience. As long as you deliver on what you promised, the promise itself is not important in absolute terms. For example, if I purchase a new black turtleneck online and select the free shipping option, I will be delighted if the turtleneck arrives on or before the promised seven days; and I will be very disappointed if it arrives on day 10. As long as the package arrives within the promised time frame, I will be satisfied with the experience. Now, let’s say you notice that all your packages are taking eight days to arrive, and your customer complaints are increasing. If you change nothing else other than the copy on your website, from seven to 10 days, you will positively affect the satisfaction of your customers.

Figure 1.1 Satisfaction can be affected through the delivery of information, which moderates expectations

Information, when provided at the right time, can be used to control your buyers’ expectations, which in turn affects their levels of satisfaction. You have complete agency over the information that you directly provide to your buyers. Your buyers, however, also source information from the collective experience of all your past customers.

Gen Y, or millennials, are the second biggest population in the history of the world (Ordun 2015). This cohort of humanity has already begun to dominate the market, not only because of their own buying power but also because of their influence on their parents and their grip on the purses of their offspring. They are a generation who are natively comfortable with processing large volumes of data, so the “overhead” of reading customer reviews or evaluating multiple alternate brands when making a purchase does not overwhelm them. According to the Google Research team, millennials research everything they buy, down to paper-clips and band-aids (Lecinski 2011). Their loyalty is earned when they feel that they have been seen, understood, or connected with—loyalty for them takes the shape of an authentic relationship built on trust. They are perfectly comfortable having this type of relationship with a brand rather than a person.

To influence a millennial buyer once, you need to earn their trust. To induce a millennial buyer to become a lifetime loyal fan, you need to form a trusted relationship with them. The relationship needs to be based on elements they genuinely care about—these buyers are not fools and abhor being “sold” to. Today’s consumers desperately want to be seen, known, and respected, and only those brands that “invest in relationships through empathy, deep understanding and insight will prevail” (Ordun 2015).

In a study of factors that affect brand loyalty in millennials (Parment 2013), the researchers found that while these buyers research everything, their decision-making criteria are based on emotion rather than reason. Unlike their parents, when millennials make buying decisions, it is not strictly for reasons that make textbook economic sense. Millennials evaluate risk in terms of social status, not financial loss.

Millennials evaluate risk in terms of social status, not financial loss.

This is a big change in how buying decisions are made today—buyers do not evaluate the features of a product and complete a rational cost/benefits analysis. They often buy in order to feel seen and raise their social standing. They may buy a product entirely because their social media friends recommended it, not because they needed what they purchased. When their expectations are met and they have positive satisfaction, they are proactive in telling their friends about it. Investing in creating strong relationships with your buyers not only affects the primary buyer to brand relationship but, through the collective experiences shared, the satisfaction of future buyers as well.

Millennials are more aware of their purchasing power and are likely to spend their cash as quickly as they acquire it (der Hovanesian 1999). Given the prevalence of this demographic on the planet and the inherent connectivity and availability of information, we all can access from our cell phones, one could argue that the parts of the world untouched by consumerism are gradually disappearing. Even at the most remote edges of the planet, we can find evidence of the existence and desire to acquire “things”—things like washing machines, fridges, and McDonald’s hamburgers. The arc of progress is marked by the acquisition of more. More clothes, more cars, more digital gadgets, and more space to store the spoils of our progress. The process of buying is a familiar activity.

The reasons why we buy are often dressed in layers of complexity and nuance: we are told that we buy to fill a void, we buy because we need, we buy because we want, we buy because we are bored, we buy because we want to belong. We buy to save time, we buy to save money, and we buy to be better in some way (Figure 1.2).

Asking the question “why do people buy” in a Google search produces pages of articles entitled “The top X reasons people buy.” Wade through the research, the marketing slogans, and the shades of psychology, and at the very core, there is only one reason anyone buys anything: we buy things because they make our lives better.

The only reason anyone buys anything is to make their life better.

If you are in the business of selling, your challenge to sell more, more often reduces to two things:

If you genuinely make their life better and deliver to their expectations, you will have the first step in creating the building blocks of a successful relationship. The mechanics of brand loyalty will take care of the rest, triggering the conditions that will systematically and consistently deliver lasting relationships between your new customers and your brand.

The Mechanics of Brand Loyalty

To understand the mechanics of brand loyalty, we need to understand the basics of how we experience the world and how we determine what makes a particular experience satisfactory. Human experience has been the focus of research for decades. It has been examined from every angle: the self, the collective, the conscious, the subconscious. Our experiences literally define our lives. In line with the arc of progress and consumerism, even the human experience has to some extent been commoditized (Figure 1.3). In 1998, Pine and Gilmore defined “the experience economy” as an emerging era characterized by a new economic offering: experiences. Experiences, like coffee and soya beans, can be bought and sold (Pine and Gilmore 1998).

Figure 1.3 Progression of perceived value as commodities are turned into goods, services, and experiences

Experiences, because of their innate value that outlasts the consumption of the cup of coffee, have a much higher intrinsic value. Unlike commodities or simple products and services, experiences continue to deliver value because they take up space in our memories. A simple example—the literal cost of a cup of take-away coffee in a country like Australia is at most $1. This includes the cost of the beans, the cost of the milk, the paper cup, the salary of the Barista, and the fixed costs of the coffee shop. Let’s say we purchase a cup of coffee from the same Barista every day for $4.50. The act of buying the coffee, of engaging in familiar banter, of having our order and name remembered transforms the utilitarian cup of coffee into a service, for which we are willing to pay a $3.50 premium. Now think about your everyday coffee—are you compelled to rave about it to your friends? Does that cup of coffee make your list of highlights for the day?

Now close your eyes (only keep them open so you can still read this). Recall the best cup of coffee that you have ever had in your life. Where were you? Who were you with? Was it cold or warm? What were you wearing? What did you smell? That best cup of coffee, which also may have cost $4.50, has actually overdelivered in value as it has become a memory. That best cup of coffee has been etched into your past experience (Figure 1.4).

Research on human memory (Mori 2008; Norman 2009) has shown that past experience, or the memory of an experience, can sometimes be more valuable than the experience itself. Not only does the passing of time serve to delete the bad parts and amplify the good parts of an experience, time can create fake memories, which are indistinguishable from actual memories. In 2009, Don Norman and his colleagues conducted a curious experiment in which they asked visitors to Disney’s theme parks about their experience of Bugs Bunny. Participants provided glowing and rave reviews of the wily rabbit, despite the impossibility of the memory (Bugs Bunny is a Warner Bros character, not a Disney one). Even when presented with the evidence, the park goers’ enjoyment of the experience was not diminished. The study concluded that the memory of an event was more important than the actual experience (Figure 1.5).

Figure 1.4 The value of past experiences grows over time, positively affecting the future expected experience of others

Your past experience affects your own perceptions of value or satisfaction and has the power to influence the buying choices of others. In aggregate, your past experience can affect the satisfaction of all future buyers. This is one of the ways in which consumers can, as a cohort, determine the destiny of your brand: the opinion of others is the most influential and powerful impetus to buy (Edelman 2010). Google’s ZMOT is the moment where the aggregate public opinion of others influences a new customer’s decision to buy. It is the moment where your past experience with a brand has become the inception of the next person’s relationship with the brand, setting the mechanics of brand loyalty into motion for another consumer.

Fitness is an area of life I have had to work hard at. If we work on the assumption that we all get something in life “for free,” the domain of sport and fitness was not the card I was given. Nevertheless, one year I signed up to run a marathon. The preparation that goes into running a marathon is not necessarily exciting. It is a matter of setting a goal and simply chipping away at that goal every single day. The amazing thing is that if you do this, you are guaranteed success. The training involved in running a marathon works, and works for anyone, because the process creates what Jim Collins describes as “the flywheel effect” (Collins 2001).

The flywheel effect is a way to describe the mechanics of a process that works, and because it works, it sets the process into motion again, perpetually (Figure 1.6). A simple fitness flywheel might look like this: I go out and exercise each morning. This makes me feel energized and good about myself. Feeling energized and positive sets my mind up to come up with creative ideas. My creative ideas generate cash flow. Cashflow gives me time to exercise, and the cycle repeats.

There is no single step in the flywheel that is most important or is the one that constitutes the big win or the big breakthrough. The flywheel works because the completion of each step “can’t help but” set the next step in motion. There are, unfortunately, no shortcuts in the flywheel: skipping a step breaks the flow of perpetual motion. The flywheel works only if you consistently and systematically do the work in each step. If you have never run, there is no single training session that you can do to be marathon ready. You have to do the work each day, and in return, the flywheel will guarantee your success.

Figure 1.6 My flywheel is kept in motion when I use time to exercise, clear my mind, generate ideas, and convert these into cashflow

The mechanics of brand loyalty work because they create a flywheel of perpetual motion. If you create a beautiful and engaging digital presence, and you address and alleviate anxieties, and you articulate how you make life better for your site visitors, then there is a good chance that the buyers will connect with your brand. The connection will lead to them deciding to purchase from you. The purchase experience will leave the buyer satisfied, and their satisfaction will entice them to share their experience with others. When others learn about your brand, they will visit your website, and the process will start again (Figure 1.7).

A break in the flywheel, or an unfavorable experience at any of the steps, will not only break the perpetual motion of the flywheel, but it can also lead to a new, negative flywheel being started. We see this all the time in fitness, where a break in routine training can lead to the start of a negative cycle of deteriorating fitness. Evidence abounds in commercial contexts too, where a negative experience causes a loyal customer to switch brands. The current state of the banking industry is a great example, where poor customer experiences offered by banks is seeing lifetime customers defect to emerging fintechs and neobanks.

Figure 1.7 The mechanics of brand loyalty: your website draws your new site visitor into a relationship with your brand, your offering exceeds expectations, which compels your buyer to tell their friends, which in turn drives new buyers to your website

The cost of negative experiences and breaks in the flywheel affect not only the buyer but also the opinions of future buyers. In real terms, one negative review is all that it takes for 51 percent of potential buyers to abandon the brand because of the uncertainty introduced and for those defected buyers to spend up to 16 percent more with competitors (Harvard Business Review 2020). Think about that—when you leave open the opportunity for a negative review, you are effectively helping your competitors outcompete you. In a larger sense, the Harvard research shows that brands with loyal customers grow revenue 2.5 times faster than brands with one-off, transactional buyers (Markey 2020). Quelch and Jocz show that brands with repeat customers and loyal fans are far more recession-proof and able to sustain more challenging economic times and downturns than competitors (Quelch and Jocz 2009). Billionaire John Paul DeJoria, founder of Paul Mitchell, sums it up nicely: “If you want to sell something, don’t be in the selling business. Be in the reorder business.”

Recall from the discussion on satisfaction that information moderates the expectations, and in turn, the satisfaction, that buyers have of an experience with your brand. Important to note that this does not mean that every experience with your brand needs to be positive—buyers will tolerate mistakes, delays, and all kinds of things going wrong as long as they are given the right information at the right time (Norman 2009).

Providing information resets the expected experience for the buyer. Consider the black turtleneck you purchased online, the one that was promised to arrive within seven days. If the package is delayed, you are dissatisfied. If the package is delayed, but you are informed of the delay in advance and perhaps even given a $10 credit off your next purchase, your expectations are reset, and you are satisfied. The provision of information can turn a negative experience into a positive one.

In the bygone days of bricks and mortar, your competitors were reasonably localized. Geography was a barrier to competition. In a digital world, your competition is always in the next tab. Your potential customer can choose you with close to zero real effort—walking from shop to shop on London’s Kings Road requires far more effort than starting another Google search. In a world where defecting to a different brand takes zero effort, the investment that you make in setting up the mechanics of brand loyalty is akin to tactics for survival in the modern digital jungle.

The traditional marketing model for how most consumer purchasing decisions are made is described as four steps:

1. Stimulus: We are made aware that mayonnaise is something we can no longer live without.

2. First Moment of Truth (FMOT): We pop down to the store and find the mayonnaise aisle. We look at the 187 different options of mayonnaise and make a decision about which to buy.

3. Moment of Truth (MOT): We choose and purchase a brand of mayonnaise.

4. Second Moment of Truth (SMOT): Our experience with the mayonnaise we chose—was it delicious? Did it live up to the promise made by the brand? (Figure 1.8).

This model was revised in 2011 by Google’s Jim Lecinski, who introduced the idea of Zero Moment of Truth (ZMOT). ZMOT is our consumption of the past experiences of others through reviews, recommendations, and Internet-based research. With the addition of ZMOT, the typical process for how we make buying decisions now looks like this:

1. Stimulus: We are made aware that mayonnaise is something we can no longer live without.

2. Zero Moment of Truth (ZMOT): We hop onto Facebook and ask our people about their favorite mayonnaise experiences.

3. First Moment of Truth (FMOT): We pop down to the store and find the mayonnaise aisle. We look at the 187 different options of mayonnaise and make a decision about which to buy.

4. Moment of Truth (MOT): We choose and purchase a brand of mayonnaise.

5. Second Moment of Truth (SMOT): Our experience with the mayonnaise we chose—was it delicious? Did it live up to the promise made by the brand?

6. The next person’s ZMOT: We post a photo of our epic hot and spicy chicken mayo sandwich on Instagram and rave about how the magic was in the mayo. The review is read by the next person, who is now left wondering how they can live without mayonnaise (Figure 1.9).

This buying process holds for all types of buying, not only for consumer goods or B2C. In commercial or industrial buying, or B2B, the process is described with slightly different words, but it is essentially the same (Figure 1.10):

1. Discovery (Stimulus)

2. Research (ZMOT)

Figure 1.10 The stages of buying correspond to the stages of experience, and the progression of the relationship between buyer and brand

3. Evaluation (FMOT)

4. Decision (MOT)

5. Experience (SMOT)

6. Referral (ZMOT)

The stages in the buying process correspond to the various types of experience. The objective experience or discovery (stimulus) is the starting point in the process. It is your offering to the market. The prior experience of other buyers (ZMOT), whether through direct referral or recommendations of others, influence your research and evaluation phases (ZMOT and FMOT), and set up your expectations. Your experience of the offering (SMOT), layered on your expectations (MOT), results in either positive or negative satisfaction. Your satisfaction affects what you tell others about the brand (ZMOT). And so on, the mechanics of brand loyalty turn the flywheel once more.

Although consumer and enterprise buyers go through the same process, the process itself can take notably different amounts of time to complete. For example, the process of realizing you can’t live without mayonnaise, to adding Best Foods Real Mayonnaise to your shopping cart can be completed in 20 seconds, while the process of deciding on which marketing analytics software as a service (SaaS) provider to choose for your growing business could take months. In industrial and enterprise procurement processes, the buying process could take years.

While time scales are important to how you manage and evolve the relationship with your potential customer in a digital space, the steps that your buyer will go through are consistent across industries, as is the degree of influence of ZMOT. Before the massive shift to online buying in 2020, Google reported that over 84 percent of all purchases begin online and that the strength of influence is extremely high across unexpected sectors including automotive, insurance, banking, credit card, travel and (as Cambridge Analytica showed us) even politics (Figure 1.11).

At the heart of the buying process is the decision, or MOT. When we are in the seller’s shoes, we tend to assume that this moment is a moment of pure rational thought. We see evidence of this in products and services that try to convince us of their value by focusing on their features. As reasonable and objective as this approach is, we tend to forget that we evaluate things subjectively and often irrationally as soon as we are standing in the buyer’s shoes.

We may wish human beings were more rational, but our brains, created for a different time and place, get in the way.

—Harvard Business Review, 1998

The headline of my current issue of Harvard Business Review reads “How to Change Anyone’s Mind” (Harvard Business Review 2021). It describes techniques that various colleagues used to persuade Steve Jobs to change his mind on decisions that had global impact, such as the development of the iPhone and App Store, audio streaming, and what eventually became the Apple TV. The techniques gently walked or persuaded Jobs from the edge of “Who the f--- would ever want this” to “Great idea, let’s build it.” In theory, Steve Jobs made his decisions objectively, rationally evaluating the pros and cons of each situation. In practice, Steve Jobs made decisions only when he felt that the idea was his to begin with. The genius of his colleagues was that they recognized this.

According to conventional economic theory, there is a base assumption that decisions are made rationally and that markets are driven by the interplay of supply and demand. In purely economic terms, we rationally establish a need and fill the need by buying a product for a price set by the forces of supply and demand—a thing we need for a price that is fair. Like Einstein, and anyone who owns more than one pair of shoes will tell you: in practice, theory and practice are not the same.

This discrepancy between what people say they do, what they theoretically should do and what they actually do is loosely what researchers have dubbed “behavioral economics” and “the psychology of persuasion” (Samson 2017; Ashraf, Camerer, and Loewenstein 2005; Cialdini 2006). The patterns that have emerged from these research fields provide crucial insights into how we actually make decisions during the buying process. Understanding the forces of persuasion and deviations from pure rationality can help us to affect buying behavior and evolve the digital brand relationship systematically and predictably.

We Make Decisions to Buy in Predictable and Irrational Ways

In the 1980s, Robert Cialdini took a gap year to work as a door-to-door vacuum cleaner salesman, a used car salesman, and a host of other “unscrupulous” sales positions to figure out how it is that we are influenced to do things that we sometimes do not want to do. His work on influence remains one of the most (pardon the pun) influential books in understanding how we make decisions (Cialdini 2006). Some 30 years later, Dan Ariely shone the light on the consistent and predictable ways in which we, like Steve Jobs, are irrational in our decision making (Ariely 2010). Until this time, and the earlier work of Daniel Kahneman (Kahneman 2013), the standard view was that we are rational in our decision making. Ariely made mainstream knowledge of the predictable patterns to our irrationality.

Together, the principles of influence and patterns of irrationality give us a sound, theoretical lens through which we can understand how it is that we make decisions when we buy. The power of these forces is that they are biologically hardwired into our DNA (Nicholson 1998). They are reliable, slow-moving signals that we can use to predict human buying behaviors in the future because, as the science has shown, even when we understand the errors in our decision-making processes, we continue to repeat the “faulty” behavior. Our reflexive response is to oblige to the faults—and we oblige for reasons that are also hardwired into our brains.

Research shows that our brains are wired to preserve energy (Markman 2015). Making decisions is hard, as it consumes energy. It is almost a matter of survival that we have a strong bias toward taking shortcuts in our decision making. In the last 100 years, the human brain has not changed from an evolutionary perspective. However, the amount of data that we are charged with processing has increased exponentially. Today, a regular person in a Western industrialized nation makes around 35,000 decisions every day (Krockow 2018). From the moment we open our eyes, we’re making decisions. These principles of influence and patterns of irrationality are so powerful as they give our brains much-needed shortcuts to making decisions.

Understanding these patterns gives us the foundation from which to create digital artifacts that will encourage a relationship to develop between the newly arrived site visitor and your brand—and the confidence to know that what you create will work, every time, in every industry, with every type of product, service, offering, or experience that you want to sell. Understanding these behavioral patterns will give you an edge in optimizing your digital footprint if used authentically. These patterns are not an invitation, or recipe, for manipulating or cheating the buyer—buyers are too informed and savvy to be made a fool of for long. A deceitful quick win will ultimately result in long-term damage to your brand (Harvard Business Review 2020). Use these tools to create a better digital relationship, not to deceive.

Authority: We Shortcut Decision Making by Deferring to Credible Authorities

Our human brains are wired to respond to authority (Cialdini 2006). Consider two factually similar arguments:

1. According to leading evolutionary psychologist Professor Nicholson, our proclivity to look to authority is part of our biogenetic destiny (Nicholson 1998).

2. I’m not an anthropologist, but I bet this hardwired deference to authority dates back to survival in primitive cultural settings.

It is not rocket science to intuit which of the above statements will be more effective in influencing your views. Today, credibility is less about survival and more about energy preservation. Our deference to credibility provides a “shortcut” to making a decision. Connecting our claims to higher authorities, such as the Harvard Business Review, or Gartner Research, The Academy Awards, Rotten Tomatoes, TripAdvisor, and using our work-endowed titles and roles, are all instant ways to gain the trust of your audience.

An endorsement by a higher authority eliminates the need to consciously weigh up the evidence and make the decision from first principles. Many successful value propositions lean on credibility from an authority: “Train, Eat and Live better with Chris Hemsworth’s team” is compelling, not because Chris Hemsworth has a PhD in nutrition or sports physiology, but because he is seen as an authority. The fact that he’s an authority in an unrelated space does not matter that much—in fact, the emergence and growth of “influencer marketing” as a discipline is based on our proclivity to defer our decision making to a famous or credible authority.

Social Proof: We Shortcut Decision Making by Leaning on the Opinions of Others

We are intrinsically wired to mimic the behavior of others (Nicholson 1998): “41 percent of the web is built on WordPress. More bloggers, small businesses, and Fortune 500 companies use WordPress than all other options combined. Join the millions of people that call WordPress.com home” makes a compelling claim that is hard to ignore—would you take the risk of choosing a different platform when 41percent of your peers have chosen WordPress? Our sense of what is the right thing is based on what others think is the right thing.

The most powerful impetus to buy is someone else’s advocacy.

—Harvard Business Review, 2010

We ingest and respond to social proof unconsciously and often rely on it as a shortcut to making decisions (Cialdini 2006). TripAdvisor star ratings are a handy shortcut to the opinions of others at a glance; ditto for product ratings on Amazon, eBay, or your favorite online store. Slogans like “4 out of 5 dentists recommend” were incredibly successful in activating our innate response of falling in line because others do. In the context of hectic lives and decision overloaded days, star ratings provide us with the social proof to make a confident decision easily.

Relative Value: We Shortcut Decision Making by Making Relative, Not Absolute, Comparisons of Value

Let’s say you are looking for accommodation for your next holiday. You look on Airbnb, or Booking.com, select your dates, and location click search. You use the resulting list of accommodations, subconsciously, as a “closed world” of choices against which you make comparisons to find the “right” choice. As we don’t have an inherent sense of the value of things, we assess what is reasonable by looking at things in relation to other, similar things. In the list of accommodation, you will likely quickly narrow by removing the outliers and compare the rest of the contenders against each other.

In marketing terms, our human propensity to make decisions through comparison gives rise to what is known as “the decoy effect.” The decoy effect is a deliberate strategy to present a number of options to the buyer, some of which are deliberately unfavorable, in a move to steer them toward choosing the option which is best for the seller. The Economist famously used this strategy when they first released their digital subscriptions, offering consumers three options:

• Option 1: Print version for $59/year

• Option 2: Digital version for $125/year

• Option 3: Print + Digital for $125/year

The second option, the decoy, worked to perfectly steer buyers to purchasing what the magazine wanted them to choose (option 3) and making the consumer feel like they chose the best value option!

It may seem that the introduction of a decoy is a little trivial, but consider the power of that decoy option again. Imagine if the magazine only presented you with two choices:

• Option 1: Print version for $59/year

• Option 2: Print + Digital for $125/year

The decision about which to choose, given these two choices, is infinitely harder, even when you know that option 2 was what you chose in the first scenario.

This principle can also be used successfully when bringing a product or offering to a market with no real competitors. In another famous case, Williams-Sonoma launched a new bread maker to the market at a price point of $275. At the time, it was the only product of its kind on the shelves at Walmart—resulting in lackluster sales as consumers eyed the bread maker with suspicion. The company introduced a comparable: a higher-featured version of the same product at double the price, and sales of the original bread maker took off. The decoy competitor provided the basis for making our irrational comparison-based decision.

Anchoring: We Shortcut Decision Making by Being Anchored to Our First Time

The first time we are exposed to a price for goods or services forms an anchor in our minds that is hard to shift from, even with the passage of time. The anchor creates a benchmark against which all future comparisons are made (Ariely 2010). It is a habit that you likely practice every day: when you buy a coffee without questioning why you are paying $4.50 for something that would make the seller a profit if sold for $1.00, or when you think about buying your next house in a particular neighborhood. Anchoring is particularly evident when the context for our decision changes, but our expectations of what is reasonable do not follow suit. For example, if you move from one city to another, you are at first anchored to the prices in your old town, making all the houses in the new area either seem extremely cheap or extremely expensive. If you sold your home in California for $1.2 million and are in the market for a $350,000 house in Las Vegas, you a far more likely to spend more at an auction than a local Las Vegan, simply because your reasonable price anchor is still set to your old context.

Anchoring is particularly visible when looking at the price sensitivity across generations. We have all heard our grandparents tell the story of “back in my day milk was $0.10 and a loaf of bread nothing over $0.20. Prices these days!” The predictable eye-roll is a reaction to the fact that your generation is anchored to a different normal price point. This chink in our thinking is notable when considering how to position your product both in relation to existing products and with regard to your target audience’s age.

Scarcity: We Shortcut Decision Making by Wanting It More When We Can’t Have It

It is human nature to want what we can’t have. The principle of scarcity goes further and shows us that we are more afraid of losing something than enticed by gaining something of equal value (Cialdini 2006; Ariely 2010). Correspondingly, we are willing to pay more for something that we think is scarce or limited—a fact exploited by every rug business on the planet that has been in its “Final Closing Down 89 percent Off” sale consistently for the last five years.

Our scarcity instinct is accelerated when we are faced with a sudden decrease in availability. The toilet paper shortage during the outbreak of the COVID pandemic is a terrific example, both of social proof and scarcity in action (Labad, González-Rodríguez, Cobo, Puntí and Farré 2021). It is a surprise that no one stopped to consider that this virus placed no extra demands on the need for toilet paper for the average citizen. The power of hardwired behavioral responses in action.

Closely related to the principle of scarcity is the common irrationality we display toward things that we have ownership, or perceived ownership, over (Ariely 2010). Signing up for a free trial of a product or test-driving a new car for the weekend allows you to “pretend” that you own the product. This act of virtual ownership is enough to trick us into feeling a sense of loss when the trial period ends, or the car is returned—and even though the thing was never ours when it is gone, we mourn as though it had been.

Take note of times when you feel the pull of signing up to a limited time, free one month only access to the new gym opening up in your neighborhood. Even as a person who thinks deeply about this stuff daily, I find myself reactive to the same formula: true story, I did indeed sign up to the limited time, free one month only access to the new gym opening up in my neighborhood next month. You probably did the same at some point too—as will your buyers when you set these forces in motion.

Free: We Shortcut Decision Making by Wanting It More When It Is Free

Along with scarcity driving us to desire something more, the price tag of free has the power to send us into a similar irrational frenzy (Ariely 2010). Let’s say you have a choice of paying $2.50 for your regular Barista made coffee or $0.50 for an instant coffee from the 7-11. Using standard economic analysis, you would do a quick cost–benefit calculation and decide to buy the Barista coffee as it is a far superior product for a great price. Now, if the price of both items were reduced by $0.50, making your Barista coffee $2.00 and the instant coffee free, economic rationality dictates that your choice should remain the same. In reality, most people choose the instant coffee with the price tag of free.

The power of free comes from the fact that it is the price point at which all risk is eliminated. Free carries with it no downside in economic terms. You, and I, have at some stage in life come home with a suitcase filled with conference loot (no, I did not need seven plastic drink bottles with the Salesforce logo emblazoned on them, or individually wrapped bars of hotel soap, which forever lie stockpiled at the back of the bathroom drawer). We took those items because there was no downside to doing so, not because there was a need or an upside. We took those items because our biological predecessors would have done the same: a life on the edge meant that even a tiny loss could jeopardize existence, hardwiring a preference for limiting the downside into our human DNA (Nicholson 1998).

Consistency: We Shortcut Decision Making by Striving to Remain Consistent, Even When Going against Ourselves

Once we take a stand, we have an almost obsessive propensity to remain consistent with our stated position (Cialdini 2006). In a study of homeowners in California, it was shown that those who were willing to have a small billboard placed in their front yard were far more likely to accept a larger, unsightly billboard than those who were not prewarned. The principle of consistency is used extensively as a strategy by telemarketers to keep you talking, walking you from the point of never having spoken to this person, or having considered installing solar panels on your roof to booking an appointment. Consistency is effectively the legendary urban myth of the frog in boiling water, only it is true.

If the deltas are small enough, you can find yourself remaining consistent with your perspective and ending up in a place you never intended to. This strategy is used successfully in hostage negotiations (Voss 2016). To win the confidence of the perpetrator, a skilled negotiator can move the hostage from a hostile position to a position of standing down by incrementally laying stepping stones that the perpetrator is biologically wired to continue stepping onto. Each step elicits a “yes, that’s right, that’s consistent with what I just said” from the perpetrator, making it almost impossible for them to reverse out due to the forces of the consistency principle.

In the context of buying goods, we fall prey to this strategy often unsuspectingly. We walk into a nice shop and start a conversation with the salesperson. The salesperson shows us a lovely dress. The dress is way more expensive than we ever intended, and not even something that we need. The salesperson says it looks great on us. We look in the mirror and agree, “yes, that’s right, it does look great on me.” On the way out, we buy a pair of earrings too because they do look fabulous with the dress we never intended to buy. This familiar pattern is replicated in the digital space so often that we may not notice it anymore. At checkout, we are presented with the option to take advantage of free shipping if we spend another $32.49. We have already committed to buying the first item and so willingly add one more to get the free shipping. The power of free plus consistency deals us an irresistible double whammy.

Inertia: We Shortcut Decision Making by Preferring To Do … Nothing

I work with companies who are looking to expand into new markets or unlock new revenue opportunities in existing markets. Quite often, these are companies that have maximized their market share in a particular market, and now seek to expand into the next market. Part of the process involves looking at the competitive landscape and an analysis of the points of difference. This analysis typically produces a matrix of features versus competitors and a bunch of ticks and crosses. Rationally, the buyer would look at such a grid and choose the provider with the most ticks.

Many businessowners think that success follows if they can show that their offering scores the most ticks. That simply having superior features, or a lower price, or both, will activate their target audience to make the switch to their brand. If their target customer is using a competitors’ services, no problem, they will leave their current provider in preference of their demonstrated and superior offering—another example where the practice and the theory do not align in reality.

In reality, the inertia of doing nothing is stronger than the potential upside, even if the upside is risk-free. Jonah Berger describes this beautifully, showing us that the certainty of today wins over the uncertainty of tomorrow (Berger 2020). The act of doing nothing wins over changing to your brand, regardless of how many more features your product has.

Your competitor list, therefore, includes inaction. To counteract inaction and get anyone to choose your brand, you must remove all the obstacles to render the desired behavior easy.

Recall that behind every single potential buyer, there is a human being who is juggling soccer drop-offs, aspirations for promotions, the desire for an occasional mid-week date, fleeting hopes of fitness, and 35,000 decisions every day. The evaluation of your product, service, or innovative offering is one more thing in their day. It is the only thing in your day. Creating conditions that trigger reflexive, biologically wired responses in decision making preserve energy. Putting in place artifacts to de-risk the unknowns of tomorrow preserve energy. Crafting active participation in the buying journey conserves energy and starts developing a sense of loss even before the purchase decision is made.

Decision Shortcuts Shorten the Buying Process

In research reported in the Harvard Business Review (Edelman 2010), the authors found that the traditional buying process (discover, evaluate, research, decide, experience) is cut down to only two steps (decide and experience) when a trusted source recommends the product or service. The prior collective experience of others not only influences the next buyer, but it fast tracks that buyer into choosing your brand.

Decide and buy. Decide and buy. The relationship you form with the next buyer reduces the buying process for future buyers from five steps to two (decide: MOT and experience: SMOT). A good relationship with your brand removes 60 percent of the obstacles that need to be overcome to make your brand the chosen one. The only thing that remains is to ensure that your next buyer falls in love with your offering (Figure 1.12).

We Fall in Love in Predictable and Irrational Ways

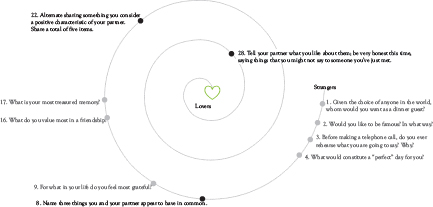

In the late 1990s, psychologist Arthur Aron and a team of researchers published a process that, when applied, could make two complete strangers fall in love (Aron, Melinat, Aron, Vallone and Bator 1997). The Experimental Generation of Interpersonal Closeness presented a set of 36 questions, which, if asked in the order prescribed, guaranteed the transition from stranger to love interest by the end of the session. This somewhat outlandish science was famously put to the test by a skeptical journalist from the New York Times, who applied the formula and—unexpectedly—found love (Len Catron 2015).

It turns out that the process for creating a deep relationship between two strangers can be applied to creating a relationship between a stranger and your brand. The 36 questions are not magical. Many are the types of questions that you would naturally ask when getting to know someone. “Given the choice of anyone in the world, whom would you want as a dinner guest” or “For what in your life do you feel most grateful?” are pretty standard conversational fare. The absolute breakthrough in Aron’s approach is the discovery that a critical element in the development of a close relationship is “sustained, escalating, reciprocal, personal self-disclosure.” If you look at the questions again, you’ll see that the order in which they are presented progressively “squeezes” the two strangers together by asking questions in an order that slowly escalates their intimacy, yet does it at a tempo that does not scare them off. As early as question eight, the couple is asked to “name three things that you and your partner have in common.” Both the language used (your partner) and the question (list things you have in common) is an enormous leap in the traditional cadence of conversations between strangers, even if considering two strangers conversing with the intent of romance, such as a first date (Figure 1.13).

Aron’s formula for love is a perfect application of Cialdini’s principle of consistency: the two strangers start with innocuous, simple questions, and with slowly increasing velocity, are thrust into a very intimate space from which they are not biologically designed to backtrack. The process of falling in love triggers our hardwired reflexes of irrationality and influence. And it works beautifully.

This book, of course, is not about traditional romance between two strangers. It is about creating romance, or the conditions for “love” between a stranger (your site visitor) and your brand. The playbook for love between strangers is valuable and applicable in this context, primarily because the person falling in love is, in fact, a person. That they are falling in love with an intangible concept like a brand is inconsequential—the process, the emotions, the actions taken, and commitments made are the same. Almost a decade ago, Spike Jonze’s movie Her challenged us to imagine whether we could have feelings for something that was “not real.” If you rewatch the same film today, only 10 years on, the concepts in the film are not nearly as far-fetched.

Figure 1.13 The thirty-six love questions generate a cadence of increasing closeness: note the way that fairly benign questions are interspersed with more vulnerable ones and how the tension immediately after a vulnerable question eases off in the next one

The idea that you can fall in love with a brand is unquestionably true today. Evidence exists at every fashion show, in every tech workspace, at every large sporting event, and in every shopping center food hall. The recipe for how to create increasing commitment and affection for your brand is described in Part II. Like the formula for real love, if done right, the process will trigger deep-rooted biological responses, almost guaranteeing success.

We Spend Our Marketing Budgets in Predictable and Irrational Ways

The marketing industry has done a stellar job of marketing the success of their own poor performance. They have conditioned us to accept that industry average conversion rates are in the order of 1 to 5 percent (Kim 2021). Consider this excerpt from Kim’s article, entitled “What’s a Good Conversion Rate? (It’s Higher Than You Think)”:

Across industries, the average landing page conversion rate was 2.35%, yet the top 25% are converting at 5.31% or higher. Ideally, you want to break into the top 10%—these are the landing pages with conversion rates of 11.45% or higher.

Let’s assume that your marketing team is brilliant, and you routinely achieve conversion rates of 11.45 percent. If your typical conversion rates are 11.45 percent, then you are, in effect, accepting that 88.55 percent of your total marketing budget is wasted. If you are at the more typical end of the spectrum, you have been conditioned to think that zero returns on 97.65 percent of your marketing dollars are an outcome to be celebrated. Other than the casino industry, modern marketing is the only industry I know of where losing 97.65 percent of your money is considered a terrific investment (Figure 1.14).

In the olden days, businesses would pay pennies for Google Ads clicks. In those days, the economics made sense. Today, Google is smarter, and the Google Ads pricing model is directly linked to demand and capacity. If you are buying keywords in medicine, SEO, or legal fields, your cost per click can be hundreds of dollars; if you are buying keywords that are not often searched for, such as pontoon repair or mid-life crisis, your cost per click may be a few dollars a click (Schewan 2021). For example, a topic like “google ads SEO” can cost between $13 and $690 per click. So, if you are a mid-sized digital marketing agency wanting to advertise your expertise with “google ads SEO,” a monthly budget of $10,000 would allow for around 30 clicks at an average cost of $350 per click. Of the 30 clicks, if we assume that your conversion rates are at the high end of market averages, say 5.31percent, you may get as many as 1.6 customers signing up to your services. You would need to make over $6,250 per customer per month simply to break even.

Figure 1.14 The cost of Google Adwords is based on popularity and competition: popular keywords in industries with deeper pockets can be hundreds of dollars per click

Google Ads revenue has been increasing year on year. Between 2018 and 2019, Google made an additional $18.35 billion from advertising revenue (Johnson 2021). To put that in context—the increase in revenue for the 2018 to 2019 financial year for Google was around the size of the GDP of many countries in Africa.

Google Ads are generating more revenue for the company each year because Google is solving for Google’s mission, not for the mission of your business (Harrison 2021). To this end, there is a tremendous incentive for things like “organic” search results to be throttled and results from more “reputable sources” to be given a leg up. This trend is not particular or limited to Google. Like Google, Facebook’s ad revenue is growing at around 17 percent per year. In 2019 to 2020, Facebook reported an additional $13.56 billion from advertising revenue.

It is most likely not a coincidence that the increase in Facebook’s advertising revenue coincides with changes to the feed algorithm, which decreases the organic reach of posts. If you are a business with 10,000 followers, it’s likely that only 650 of your fans will see one of your posts. According to Hubspot, Facebook reports that “you should assume organic reach will eventually arrive at zero.” Once again, there is strong evidence to suggest that Facebook is solving for its own mission, not the mission of your business.

Following the money flows, we can make the fair prediction that Google, Facebook, Instagram, or YouTube (insert your favorite social media platform) are solving for their own business models, which includes creating new ways to squeeze more advertising dollars out of your business. Coupled with recent changes in the name of data privacy, restrictions on how cookies are handled at the operating system level has the potential to render strategies based on adwords far less effective than the current industry averages. According to Google’s research, most publishers could lose 50 to 70 percent of their revenue if they don’t reconfigure their approach to advertising and data management by 2022.

The future is not random—the way you spend your marketing dollars, the strategy you have for creating long term, recession-proof revenue streams needs your immediate attention. The signals are all here now. Schwartz could see them back in 1997: “Marketers should not be on the web for exposure, they should be on the web for results.” Retention is the new acquisition.

How do you get retention? Excellent that you asked.

Summary: The Formula for Digital Brand Romance

The creation of an excellent digital brand relationship can be scripted. Spending decades working with brands worldwide and researching buying behavior as it manifests in technology, psychology, and behavioral economics has led me to discover six critical moments in the customer journey, from first contact with a brand to ultimate brand loyalty and advocacy.

In Part II, you will learn the script or process for digital brand romance: the ADORE processTM. The ADORE processTM has been tested with brands in a wide range of industries: from edible seaweed to restaurant booking platforms, architectural timber producers, fintech apps, construction SaaS systems, accounting, technology, old fashioned engineering firms and modern marketing agencies. Consistently, the brands that apply the ADORE processTM realize above-average conversions, significantly increased retentions, and higher and accelerated sales rates. When you understand the basis of ADORE, you will be able to spot and resolve issues in the digital artifacts that define your relationships with buyers. This will allow you to optimize your website, e-mail marketing campaigns, apps, and e-commerce stores for lasting and meaningful relationships that transcend individual transactions.