As useful as these XML transformations can be, they are not very simple to implement. In fact, rather than trying to specify the transformation of XML in the original XML 1.0 specification, three separate recommendations have come out to define how transformations should occur. Although one of these (XPath) is also used in the XPointer specification, by far the most common use of the components we outline here is to transform XML from one format into another.

Because these three specifications are tied together tightly, and are almost always used in concert, there is rarely a clear distinction between them. This can often make for a discussion that is easy to understand, but not necessarily technically correct. In other words, the term XSLT, which refers specifically to extensible stylesheet transformations, is often applied to both extensible stylesheets (XSL) and XPath. In the same fashion, XSL is often used as a grouping term for all three technologies. In this section, we will distinguish among the three recommendations, and remain true to the letter of the specifications outlining these technologies. However, in the interest of clarity, we will resume using XSL and XSLT interchangeably to refer to the complete transformation process throughout the rest of the book. Although this may not follow the letter of these specifications, it certainly follows their spirit, as well as helping to avoid unnecessary confusion.

XSL is the extensible stylesheet language. It is defined as a language for expressing stylesheets. This broad definition is broken down into two parts:

XSL is a language for transforming XML documents.

XSL is an XML vocabulary for specifying the formatting of XML documents.

These definitions are similar, but one deals with moving from one XML document form to another, while the other is more focused on the actual presentation of content within each document. Perhaps a clearer definition would be to say that XSL handles the specification of how to transform a document from format A to format B. The components of the language handle the processing and identification of the constructs used to do this.

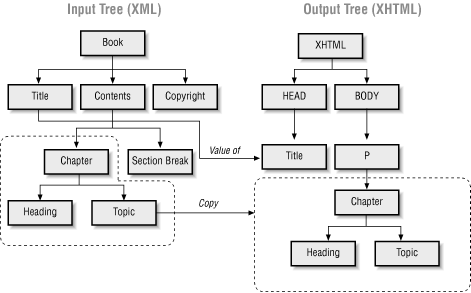

The most important concept to begin to understand in XSL is that all data within XSL processing stages is in tree structures (see Figure 6.1). In fact, the rules you define using XSL are themselves held in a tree structure. This allows simple processing of the hierarchical structure of XML documents. Templates are used to match the root element of the XML document being processed. Then “leaf” rules are applied to “leaf” elements, filtering down to the most nested elements. At any point in this progression, elements can be processed, styled, ignored, copied, or have a variety of other things done to them.

A nice advantage of this tree structure is that it allows the grouping of XML documents to be maintained. If element A contains elements B and C, and element A is moved or copied, the elements contained within it receive the same treatment.

This makes the handling of large data sections that need to receive the same treatment fast and easy to notate, as well as concise, in the XSL stylesheet. We will look more at how this tree is actually constructed when we talk specifically about XSLT in the next section.

Almost the entirety of the XSL specification is concerned with

defining formatting

objects

. A formatting object is based on a

large model, not surprisingly called the

formatting

model. This model is all about a set of objects that are fed as input

into a formatter. This formatter applies the objects to the document,

either in whole or in part, and what results is a new document that

consists of all or part of the data from the original XML document in

a format specific to the objects the formatter used. Because this is

such a vague, shadowy concept, the XSL specification attempts to

define a concrete model these objects should conform to. In other

words, a large set of properties and vocabulary make up the set of

features that formatting objects can use. These include the types of

areas that may be visualized by the objects, the properties of lines,

fonts, graphics, and other visual objects, inline and block

formatting objects, and a wealth of other syntactical constructs.

Formatting objects are used particularly heavily when converting textual XML data into binary formats, such as PDF files, images, or document formats such as Microsoft Word. For transforming XML data to another textual format, these objects are seldom used explicitly. Although an underlying part of the stylesheet logic, formatting objects are rarely directly invoked, since the resulting textual data often conforms to another predefined markup language such as HTML. Because most enterprise applications today are at least in some part based on web architecture, and use a browser as a client, we will spend most of our time looking at transformations to HTML and XHTML. While this causes us to cover formatting objects lightly, the topic is broad enough to merit its own coverage in a separate book or web site. For further information, you should consult the XSL specification at http://www.w3.org/TR/WD-xsl.

The second component of XML transformations is XSL Transformations. XSLT is the language that specifies the conversion of a document from one format to another. The syntax used within XSLT is generally concerned with the textual transformations we discussed earlier that do not result in binary data output. For example, XSLT is instrumental is generating HTML or WML (Wireless Markup Language) from an XML document. In fact, the XSLT specification outlines the syntax of an XSL stylesheet more explicitly than the XSL specification itself!

Just as in the case of XSL, XSLT is always well-formed, valid XML. A DTD is defined for XSL and XSLT that delineates the allowed constructs. For this reason, you should only have to learn new syntax to use XSLT as opposed to the entirely new structures that had to be digested to use DTDs themselves. Just as in XSL, XSLT is based on a hierarchical tree structure of data, where nested elements are leaves, or children, of their parents. XSLT provides a mechanism for matching patterns within the original XML document (using an XPath expression, which we look at next), and applying formatting to that data. This could result in simply outputting the data without the unwanted XML element names, or inserting the data into a complex HTML table and displaying it to the user with highlighting and coloring. XSLT also provides syntax for many common operators, such as conditionals, copying of document tree fragments, advanced pattern matching, and the ability to access elements within the input XML data in an absolute and relative path structure. All these constructs are designed to ease the process of transforming an XML document into a new format.

The final piece of the XML transformations puzzle, XPath provides a mechanism for referring to the wide variety of element and attribute names and values in an XML document. As we mentioned earlier, many XML specifications are now using XPath, but this discussion is only concerned with its use in XSLT. With the complex structure that an XML document can have, locating one specific element or set of elements can be difficult. This is made more difficult because access to a DTD or other set of constraints that outlines the document’s structure cannot be assumed; documents that are not validated must be able to be transformed just as valid documents can. To accomplish this addressing of elements, XPath defines syntax in line with the tree structure of XML and the XSLT processes and constructs that use it.

Referencing any element or attribute within an XML document is most easily accomplished by specifying the path to the element relative to the current element being processed. In other words, if element B is the current element and element C and element D are nested within it, a relative path most easily locates them. This is similar to the relative paths used in operating system directory structures. At the same time, XPath also defines addressing for elements relative to the root of a document. This covers the common case of needing to reference an element not within the current element’s scope; in other words, an element that is not nested within the element being processed. Finally, XPath defines syntax for actual pattern matching; find an element whose parent is element E and which has a sibling element F. This fills in the gaps left between the absolute and relative paths. In all these expressions, attributes can be used as well, with similar matching abilities. Several examples are shown in Example 6.1.

Example 6-1. XPath Expressions

<!-- Match the element named JavaXML:Book relative to

the current element -->

<xsl:value-of select="JavaXML:Book" />

<!-- Match the element named JavaXML:Contents nested within the

JavaXML:Book element -->

<xsl:value-of select="JavaXML:Book/JavaXML:Contents" />

<!-- Match the JavaXML:Contents element using an absolute path -->

<xsl:value-of select="/JavaXML:Book/JavaXML:Contents" />

<!-- Match the focus attribute of the current element -->

<xsl:value-of select="@focus" />

<!-- Match the focus attribute of the JavaXML:Chapter element -->

<xsl:value-of select="JavaXML:Chapter/@focus" />Because often the input document is not fixed, an XPath expression

can result in the evaluation of no input data, one input element or

attribute, or multiple input elements and attributes. This makes

XPath very useful and handy; it also causes the introduction of some

additional terms. The result of evaluating an XPath expression is

generally referred to as a node

set

.

This shouldn’t be surprising, as we have already been loosely

using the term “node” and will continue to do so; it is

also in line with the idea of a hierarchical or tree structure, often

dealt with in terms of its leaves, or nodes. The resultant node set

can then be transformed, copied, or ignored, or have any other legal

operation performed on it. In addition to expressions to select node

sets, XPath also defines several node set functions, such as

not( )

and count( )

. These functions take in a node set as

input (typically in the form of an XPath expression) and then further

pare the results. All of these expressions and functions are

collectively part of the XPath specification and XPath

implementations; however, XPath is also often used to signify any

expression that conforms to the specification itself. This, like XSL

and XSLT, while not always technically correct, makes it easier to

talk about XSL and XPath.

To explain any of these three components’ syntax by themselves would simply be a rehash of the specifications. Instead, we will again use our example XML document. As a demonstration of an XML transformation, we will look at how to create an HTML document fragment from our table of contents data. In this way we will look at XSL, XSLT, and XPath in the context of a practical use, continuing to try to make these discussions of syntax relevant to you as a developer.