A network lets computers communicate with each other, sharing files, email, and much more. Unix systems have been networked for more than 25 years, and Macintosh systems have always had networking as an integral part of the system design from the very first system released in 1984.

This chapter introduces Unix networking: remotely accessing your Mac from other computers and copying files between computers.

There may be times when you need to access your Mac, but you can’t get to the desk it’s sitting on. If you’re working on a different computer, you may not have the time or inclination to stop what you’re doing, walk over to your Mac, and log in (laziness may not be the only reason for this: perhaps someone else is using your Mac when you need to get on it or perhaps your Mac is miles away). Mac OS X’s file sharing (System Preferences → Sharing) can let you access your files, but there may be times you want to use the computer interactively, perhaps to move files around, search for a particular file, or perform a system maintenance task.

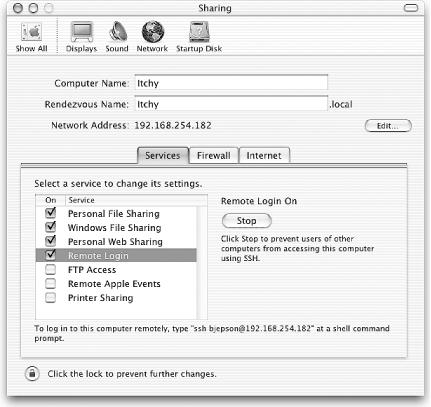

If you enable Remote Login under System Preferences → Sharing, you can access your Mac’s Unix shell from any networked computer that can run SSH (http://www.ssh.com), OpenSSH (http://www.openssh.org), or a compatible application such as PuTTY (a Windows implementation of SSH available at http://www.chiark.greenend.org.uk/~sgtatham/putty/). SSH and OpenSSH can be installed on many Unix systems, and OpenSSH is included with many Linux distributions as well as Mac OS X.

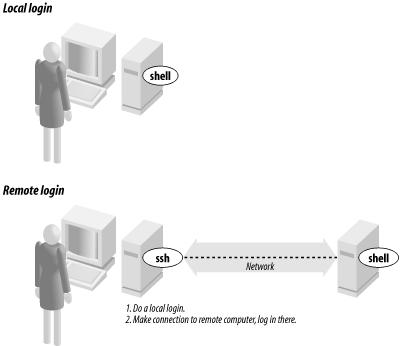

Figure 7-1 shows how remote login programs such as

ssh work. In a local login, you interact directly

with the shell program running on your local system. In a remote

login, you run a remote-access program on your local system; that

program lets you interact with a shell program on the remote system.

When you enable Remote Login, the Sharing panel will display instructions for logging into your Mac from another computer. This message is shown in Figure 7-2.

To log in to your Mac from a remote Unix system, use the command shown in the Sharing panel, as shown in the following sample session (the first time you connect, you’ll be asked to vouch for your Mac’s authenticity):

Last login: Sun Nov 17 21:21:37 2002 from 192.168.254.182 Sun Microsystems Inc. SunOS 5.9 Generic May 2002 bash-2.05$ssh [email protected]The authenticity of host '192.168.254.182' can't be established. RSA key fingerprint in md5 is: 0a:9c:48:8c:9d:d1:b7:18:1b:3b:02:4a:dd:02:72:2a Are you sure you want to continue connecting(yes/no)?yesWarning: Permanently added '192.168.254.182' (RSA) to the list of known hosts. [email protected]'s password: Last login: Sun Nov 17 21:04:30 2002 Welcome to Darwin! %

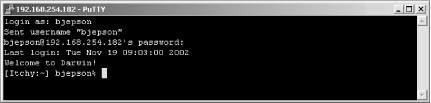

To log in to your Mac from a Windows machine using PuTTY, launch the PuTTY application, specify SSH (the default is to use the Telnet protocol described later), and type in your Mac OS X system’s IP address as shown in the Mac’s Sharing panel. PuTTY will prompt you for your Mac OS X username and password. Figure 7-3 shows a sample PuTTY session.

You can also use the Sharing preferences panel to enable your system’s Web and FTP server. Start Personal Web Sharing to enable the Web server. Other users can access the main home page (located in /Library/WebServer/Documents) using http://address, where address is your machine’s IP address or host name (see the sidebar Remote Access and the Outside World if you are using an Airport Base Station or other router between your network and the Internet).

Start FTP Access to enable remote users to use FTP to connect to your system. Again, remote users should use your machine’s IP address or hostname to connect.

You can also

connect to other systems from Mac OS X. To do so, launch the Terminal

application. Then start a program that connects to the remote

computer. In addition to ssh, some typical

programs for connecting over a computer network are

telnet, rsh (remote shell), or

rlogin (remote login). All of these are supported

and included with Mac OS X. In any case, when you log off the remote

computer, the remote login program quits and you get another shell

prompt from your Mac.

The syntax for most remote login programs is:

program-name remote-hostnameFor example, when Dr. Nelson wants to connect to the remote computer

named biolab.medu.edu, she’d

first make a local login to her Mac named fuzzy

by launching Terminal. Next, she’d use the

telnet program to reach the remote computer. Her

session would look something like this:

Welcome to Darwin! fuzzy%telnet biolab.medu.eduMedical University Biology Laboratory biolab.medu.edu login:jdnelsonPassword: biolab$ . . . biolab$exitConnection closed by foreign host. fuzzy%

Her accounts have shell prompts that include the hostname. This reminds her when she’s logged in remotely. If you use more than one system but don’t have the hostname in your prompt, see Section 4.2.1 or Section 10.1 to find out how to add it.

Tip

When you’re logged on to a remote system, keep in

mind that the commands you type will take effect on the remote

system, not your local one! For instance, if you use

lpr to print a file, the printer it comes out of

may be very far away.

The

programs

rsh (also called rlogin) and

ssh generally don’t give you a

login: prompt. These programs assume that your

remote username is the same as your local username. If

they’re different, give your remote username on the

command line of the remote login program, as shown in the next

example.

You may be able to log in without typing your remote password or passphrase.[8] Otherwise, you’ll be prompted after entering the command line.

Following are four sample ssh and

rsh command lines. The first pair shows how to log

in to the remote system, biolab.medu.edu, when

your username is the same on both the local and remote systems. The

second pair shows how to log in if your remote username is different

(in this case, jdnelson); note that the Mac OS X

versions of ssh and rsh may

support both syntaxes shown depending on how the remote host is

configured:

%ssh biolab.medu.edu%rsh biolab.medu.edu%ssh [email protected]%rsh -l jdnelson biolab.medu.edu

Today’s

Internet and other

public networks have users who try to break into computers and snoop

on other network users. While the popular media calls these people

hackers

,

most hackers are self-respecting programmers who enjoy pushing the

envelope of technology. These evildoers are better known as

crackers

.

Most remote login programs (and file transfer programs, which we

cover later in this chapter) were designed 20 years ago or more, when

networks were friendly places with cooperative users. Those programs

(many versions of telnet and

rsh, for instance) make a

cracker’s job easy. They transmit your data across

the network in a way that allows even the most inexperienced crackers

to read it, and they either send your password along, visible to the

crackers. Worse, some of these utilities can be configured to allow

access without passwords.

SSH is different; it was designed with security in mind. It sends your password (and everything else transmitted or received during your SSH session) in a secure way. A good place to get more details on SSH is the book SSH: The Secure Shell, by Daniel J. Barrett and Richard Silverman (O’Reilly).

[8] In ssh, you can run an

agent program, such as

ssh-agent, that asks for your passphrase once,

then handles authentication every time you run ssh

or scp afterward.