CHAPTER 4

Personal Assessment: Is Wind Power Right for You?

All energy prices have gone up, and wind is a pretty hot commodity right now. There is more demand than there is supply right now.

–MICHAEL SLOAN

The next few chapters will provide information on the tools, methods of observation, and mathematical formulas you’ll need to start determining if a small wind system will work for you. Initially, we look at your personal assessment: a way to measure your needs, your home’s energy load, and your personal limits. This is followed by assessing your site. Topics will include prevailing wind patterns, wind volume versus wind speed, wind power categories, where wind is likely the most promising within the continental United States and globally, and strategies to most effectively convert wind into usable energy. Determining the feasibility of any project includes consideration of personal lifestyle, costs, municipal regulations, grid compatibility, and social friction.

Before we bring out the tools to evaluate your site for wind energy, let’s stop and evaluate your relationship with the wind and wind energy technology (Figure 4-1). We’re not talking about deep emotional stuff. We’re talking about what you have brought to the table to choose wind over other options.

FIGURE 4-1 There are lots of fun things that spin, but only you can decide if a wind turbine is right for you. Brian Clark Howard.

Before you put up your defenses, let us say that you can pass this chapter if you feel any of these apply to you:

1. You don’t care how much it will cost you. You want a wind system and that is that!

2. Energy efficiency is not your game. In fact, you’re hoping a wind system will allow you to use more energy.

3. You represent the municipality. You want it, and that is good enough reason.

4. You live in a very energy-efficient home already and are charged excessively high electric rates.

5. You live in a very high average wind region, and you want to lasso this sucker.

6. You live way off-grid or on a boat.

If you have one of these scenarios, be our guest and move on. You are probably ready to invest in a wind system. For the rest of us, read on.

So, are you thinking about why you leapt into wind energy? Think about it as we discuss a few things:

Namely, (1) your emotional needs, (2) your energy needs, (3) your relationship to the grid, and (4) your relationship with your community.

Nothing Personal: Your Motivations

We are not here to tell you that installing a wind turbine is a need, in the same way that food, water, and air are needs. A wind turbine is simply one way to get energy for all the things you need, or at least think you need.

We can’t ignore a trend that exists in most developed nations: people buy things because they think they need them. It fills something missing, or it makes a statement. Some people buy wind turbines because they represent something, just like the house, the car, and the clothing. An equally valid reason to buy a wind turbine is to save or even to make money. This is a nonjudgment zone. It is not always important to know the real reason, but it can help in the design, because you can find the limits of what you are willing to do to satisfy this need.

First the wind. Sure, you see its power as it blows over your garbage cans, or tousles the branches of your trees, or sends waves through the crops on a farm. You hear it whistle around buildings. You’ve also seen the damage it can levy in storms. Wind moves around like it’s still the Wild West. It is perpetually unleashed for its own pleasure (not really; it isn’t a thinking thing, you know). But you want to harness this energy. You want it enough that you bought this book. Perhaps, this book was near other titles on solar, geothermal, and other renewable energy resources; or you may be reading this in the light from your wood pellet stove. Or perhaps, the energy from the wind is an option that stands out from the rest.

Then there is the technology part. Sure, it looks sleek standing there on your property. It is the most visible of the renewable energy options. Along with micro-hydro, it is a rare electric generation system that you can actually see working, without having to look at digital-read outs or your electric bill. A wind system commands attention, being that it towers above all other surrounding objects (unless it is on your boat or it is installed improperly). And if you have a plug-in hybrid or electric car, this sucker could cut your trips to the fuel station (and, by the way, it looks really sexy next to your ride).

Wind is the best sibling for a solar photovoltaic system. If you live in a temperate zone, sunshine is more plentiful during the summer. Meanwhile, the wind energy is not as strong and frequent. But in the winter, the wind is an unforgiving force, more than compensating for the shorter days and lower solar radiation. Wind technology almost seems natural, doesn’t it?

What we are leading you to is this: what is this relationship to the wind turbine worth to you?

Let’s play a simple game of priority to help you decide if wind is for you.

This is how the game works. First, we tell you what each term means, then you fill each box in Table 4-1 with a + or – symbol. The plus signifies that the item in the row is more important than the item in the column. Since we can’t compare something against itself, those boxes are blacked out.

What is the goal? To determine the most important reasons in your life and cast them onto your choice for wind power. For example, if given a situation of receiving or saving money at the risk of losing a close friendship, which is more important to you? But the twist is that we relate it to wind electric systems and see if something stands out.

Here are the terms:

Money: Any financial benefit you would get for having a wind turbine. Be it a feed-in tariff, tax incentive, rebate from your power authority, or money saved.

Friendship: Any friends gained or lost due to this big decision. Remember that a wind turbine is a personal decision, but if you don’t live alone or isolated from others, it could be an issue.

Popularity: Gained or lost attention from human beings (as opposed to birds and bats) as a result of this towering turbine. If you are a business, or you love to share, popularity should be a good thing.

Personal Achievement: Acknowledgment of meeting the challenge of putting up a wind turbine and keeping it maintained for years to come.

Independence: Freedom from your electric bills or the power authority, or if you moved to an isolated place, the rest of the world.

Acceptance: Tolerance of the wind turbine by your local community, particularly your neighbors (who hopefully won’t be too angry). For many, there is the tendency to conform to others.

TABLE 4-1 This handy chart can help you figure out your motivation for wanting a wind turbine. Try it!

Now that you have completed the table, this is how we determine your priorities. Simply count the number of times you put a + for each term. (The maximum number for any item is 5.)

You and only you can interpret the results. Although the relationship between these values can be telling, remind yourself that this is only a sample activity, asking you to prioritize under extreme circumstances. We don’t know of any divorces or church excommunications as a result of turbine installations. We do know of families who installed a turbine and then felt a sense of independence, yet didn’t realize how much more invigorating it was to know that their community welcomed it, and they later became a local source of information on the technology.

If this kind of decision making doesn’t appeal to you, we’d still encourage you to try to think about what you really want before you put money on the table for something that will be around for 20 or 30 years.

Determining Your Relationship to the Grid

What is going to be your relationship to the power grid? To some, Grid is God. In other words, they wouldn’t think of anything but having their home or business hooked up to the grid. They grew up with electric poles on their street, so why would they want to do anything else? When they plug things in, they work. They may ask, “As long as I don’t have to think about it, what is the problem?”

Then there is the polar opposite (Figure 4-2). Perhaps the ratepayers who say the big utility companies do not do them justice. These folks would rather go out on their own, count their kilowatts, and wave to the naysayers who still pay high bills, as they sit comfortably behind their energy-efficient windows, watching their Superbowl or World Cup game from the satellite dish … during a blackout. There are also boaters who prefer to not have to charge up at the dock. Or consider that hunter’s paradise in the Catskills mountain range, where stretching a copper electric cable from the nearest part of the grid could be more expensive than 50 years of round trips to the getaway bungalow.

FIGURE 4-2 If you have a cabin in the wilderness or need to pump water for cows on a remote ranch, it may be more cost-effective to have a small wind turbine off the grid, like this 1 kW Whisper on a ranch in Wheeler, Texas. Elliott Bayly/DOE/NREL.

Then there is the largest group of people, who are driving the most growth in the small wind industry: the best-of-both-worlds people. They want to hook up to the grid, but see no reason why they can’t save money (net-metering) or even earn money (feed-in tariffs).

These clusters are in no way suggesting what type of person you are; they are merely a colorful way to illustrate what type of bond people commonly keep to their public utility. In sum, there are several options we will review:

1. Keep the grid, and buy someone else’s renewable energy. This option is available to many already, and if you call your power authority, they may be able to sign you up right away.

2. Get me off the grid, and bring on the batteries or some other storage mechanism. This can be a rewarding achievement, but except for boats or separate special functions (pumping water), it certainly is not the easiest or the cheapest of the options.

3. Share my surplus with the grid. This is a popular choice for those locations that offer you the option to offset your usage by banking your electrical surplus. This is one of the most popular options outside of feed-in tariffs, and it permits you to achieve savings as soon as you connect to the public utility.

4. Be my public utility. This is an option that exists in many nations, especially in Europe. If you are fortunate to have such mechanisms as government-subsidized feed-in tariffs (FITs), you will basically be your own power plant, and will be paid handsomely for every kilowatt-hour that you produce. The hook-ups are as easy as net-metering, and if you keep your system maintained, you will earn income for 20 years or more from either your public utility or your government (see Chapter 6).

There are advantages and disadvantages to each option, and you must choose the relationship you feel most comfortable with (Figure 4-3). In many cases, you can change relationships if it doesn’t work out, although that change may be expensive. Some equipment, like inverters, may have to be changed to comply with the public utility. With FITs, some contract agreements may have penalties if you opt to fold out or are not making enough power to meet your quota.

FIGURE 4-3 Like this California homeowner, you can choose to connect your small wind turbine to the grid or keep it separate. Bergey Windpower/DOE/NREL.

Now, let’s move from your person to something you spend much of your time with: your home.

How Energy-Efficient Is Your Home or Business?

Welcome! If you are hoping to get your wind turbine to power your home or business, we can do that, and we can do that easy! The qualifications are simple: cut your energy demand by half, and then come back to us. By that time, you will have saved enough money to buy the turbine. Have a nice day. Don’t let the foam-core door hit you on the way out.

If you really want to proceed without making your home or business efficient first, you are wasting a lot more money. We get into costs in detail in Chapter 6, but we think it’s important to give you a glimpse now. We are making the assumption that, ideally, you would like to have a turbine that at least covers your energy costs.

Later, we go into more detail about the economic feasibility of wind turbines. But if we were to spend a few hours doing some paperwork and end up saving you half the price of installing a wind turbine that would power your home for 20 to 30 years, would you be interested? Of course you would.

Table 4-2 sizes wind turbines to the average home energy usage, exclusive of the actual average wind speeds of the regions. This is just the wind turbine, without the tower or the rest of the components and installation, such as the backhoe and crane, concrete and rebar, electrical components, shipping, and sales tax. KaChing!

All of us could probably reduce our energy demand significantly; however, as a society, we are not always conscious of the possibility. The household energy use values noted here are affected by a number of factors, among them social, economic, political, climate, and availability of energy-efficient technology. Perhaps not surprisingly, in Europe and California, there are more robust incentives and pressures for conservation and efficiency.

TABLE 4-2 Average Energy Use per Household by Region

Normally, we don’t think in terms of counting kilowatt-hours. You may wonder what you are going to have to do—shut off the lights, not operate the pool, watch less TV—have less fun. Well, in this activity, you will get to count the beads, so to speak, and once you get to the “numbers,” we don’t necessarily presume that your lifestyle is going to change. If a few replacements or modest modifications can save up to 20 to 60 percent of your energy use, you will shave thousands of dollars off the purchase of your wind turbine. Why? Because you can size down the turbine to a model that meets your reduced load. KaChing coming in!

In this brief interlude, we will determine your electricity load analysis and current costs, and set some goals. The priority here is to find out your situation before you try to find solutions. No buying till we assess. Agreed?

It is only a three-step process:

1. Calculate your average annual consumption from your bill(s).

2. Identify how much energy each individual item uses.

3. Identify what you can do to reduce energy use cost-effectively.

Calculating Average Annual Consumption

First, you have to ask how much are you spending. To do this, start by looking at your electric bill. If you recently entered the building or did some renovations, we will cover that shortly.

On your bill, note the total for kilowatt-hours (kWh): that is how much energy you used. And it will fluctuate day to day, month to month, throughout the year. If you want to know your average energy demand for the year, go through your past bills or contact customer service for your power utility. Provide them your electric account number located on the bill, then tell them that you are considering installing a wind turbine and need: 12 months (a full year) of your electricity consumption in kilowatt-hours.

Now you have taken the first step. Some people include more years just in case the most recent one was unusual. Perhaps there was construction, with high usage of power tools, or perhaps you were vacationing in your summer home for three months.

This Thing Costs How Much to Use Every Year?

Where are all the costs coming from? Let’s take a look at an average U.S. home (Figure 4-4). If you live in a developed nation in a temperate zone, it is likely similar.

And in 2008, a survey shows the U.S. electric consumption breakdown (Table 4-3).

FIGURE 4-4 A summary view of average energy consumption in U.S. homes over the course of a year. Energy Information Administration.

TABLE 4-3 Average U.S. Home Electricity Consumption in 20082

This might give you a glimpse into how much your home or facility is using, but it doesn’t escape the fact that if you are going to make a big purchase, it is best to have a more detailed list of your energy needs.

How would you know one item’s usage from another? You see 100 watts, 1,000 watts. Made no difference to you in the past, so long as it worked. Then, the first year of operating the new pool, or a hot summer with your central air, you get your electric bill and … SLAP … you just found the hidden big cost. Hidden? It is right there for you to calculate, isn’t it? I have to calculate? And so starts the dilemma.

Let’s approach this with an analogy. Let’s go to the supermarket. Take a cart, and select whatever you like for your family. Place it in the cart and then go home. Do this for a month. Don’t even bother looking at the prices. Prices don’t matter here. What? It’s free? Oh, no. You get a cumulative bill at the end of the month. And it will tell you exactly how much you owe. But it won’t tell you how much an item cost, the quantity, or even the name of the item. Just the amount you owe. That is exactly what you have going on with your electric bill.

If you’re lucky, you may have received a smart meter, which is an advanced meter that records consumption in intervals of an hour or less and communicates that information to the utility for monitoring and billing purposes.3 Even so, that meter will not tell you each appliance’s individual usage (although that technology is currently being developed, and should become available in the near future). Today, even a smart meter can only provide a digital grocery bill of the sum kilowatt-hours of your total house—just in a smaller time period.

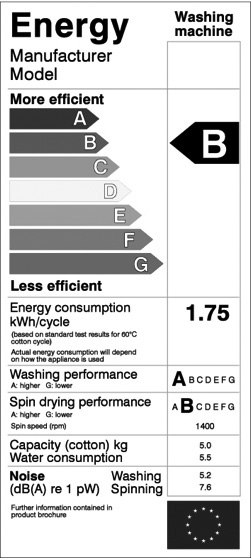

To make it a little easier, many nations do require some form of energy-efficiency rating labels on a number of appliances. Figures 4-5 and 4-6 show a few examples, and there are many more listed in this footnote.4 These labels show how many kilowatt-hours the device will use for a year of average usage and the cost based on the average electric rate. This is definitely helpful, but if you really want to get a handle on your energy use, you should still do the calculations. For example, Kevin owns an electric range oven but never cooks, so that can be calculated as zero watt-hours.

FIGURE 4-5 An example of an energy-efficiency label in the European Union. Andrew Dunn/Wikimedia Commons.

FIGURE 4-6 A sample energy-efficiency label for the United States’ Energy Star program. EPA.

But perhaps Chef Chewy Munchalot, who lives in an area with the relatively high electric rate of 18 cents per kilowatt-hour, likes to make his culinary delights every day in his convection oven. According to the energy label, in small print, it states that the estimated annual cost is based on an average price of 11 cents per kWh. Chewy is wise to overlook the “average” calculation, estimate the number of hours he actually uses his oven, and plug the values into a handy-dandy calculator ($.18 × wattage of a range oven × 2hrs/day = his cost/day.)

Most electronics devices have a nameplate with the information you need to get started (Figure 4-7). If you find something with no wattage listed, you are not out of luck. You just need to make a simple calculation. As in Figure 4-7, many devices will list the rated voltage (V) and amperage (A). Simply multiply these values and you have the wattage. So, for example, if you have a phone charger that has an input voltage of 120 volts (120V) and an amperage of 5 amps (5A), 120 × 5 = 600, so the power would be 600 watts. If your charger says it is rated at 120V to 240V, and you take it to Europe, your input voltage would likely be 240V instead of 120V (handy that it still works, right?).

FIGURE 4-7 If you aren’t sure how much energy a device takes to run, you can calculate it by looking at the nameplate. Multiply the rated voltage (V) and amperage (A) to get the wattage. Brian Clark Howard.

Next, determine the hours you use the item. And think year round. Winter days in temperate zones are colder and get less light, so that means more hours of lighting and heating.

Although it doesn’t seem like glamorous work, without a good energy estimate, there is a high likelihood of underestimating your energy load and falling short of your ideal. This is a serious concern, because upgrading a wind system is not so easy. UPS or FedEx won’t uninstall your turbine when you need to return it for a bigger one. The other scenario is that you overestimate and spend more than you need. Unless you have a feed-in tariff, the higher cost of the system could outweigh the benefits. Power authorities are not traditionally in the business of buying energy from small producers, and they usually pay you only a fraction of the retail price that they charge their customers. If you are off-grid, you now have to buy more storage to handle the surplus load. Yikes!

Wait! There are easy options to quickly make an energy load analysis. You can do this. There are four approaches, and one will be comfortable for you.

Auditing Your Energy Consumption

If you want to precisely determine how much energy you are using, you’ll need an energy audit. Don’t worry, it’s relatively easy, and there are lots of folks who can help (Figure 4-8).

FIGURE 4-8 The best way to get a handle on your energy use is to actually measure it with an energy audit. You can hire a pro, do it yourself with pencil and paper, or buy or rent some gadgets that can help improve your accuracy. Kevin Shea.

Option 1: Get a Professional Home Energy Audit

Getting professional help is good. Many localities offer free audits to identify energy-saving repairs. An energy audit is a comprehensive inspection, survey, and analysis of energy flows in a building, with the goal to reduce the amount of energy consumption. It is not unreasonable to pay up to $500 to have someone come into your home and give you a detailed report. But their suggestions will likely get you to save that back the first year. Many auditors offer to make the improvements themselves, although you may also want to get a second opinion.

If you want to know what auditors do and their tools of trade (blower doors, thermal cameras, etc.), there are many videos and webpages online that demonstrate their focus. Just search online for “home energy audit video.”

Option 2: DIY Home Energy Audit

If you live in the United States, you can use the Department of Energy’s Home Energy Saver calculator (at hes.lbl.gov) for a do-it-yourself (DIY) energy audit. Just enter your ZIP code and some personal information, including the size of your home, and you’ll get ideas on how you can save money around the house.

If you want to learn how to do a home energy audit by yourself, you can try this footnoted video link,5 or check out the DIY home energy audit guide on The Daily Green (www.thedailygreen.com).

These methods attempt to be comprehensive, and rightly so. Heating and cooling systems generally require electric fans, blowers, and water circulators. The less you need to heat or cool your home, the lower your electric load.

For those who cannot find an online auto-auditor, the focus will be on electrical energy consumption. You will need to prepare a chart. The simplest way is to make a spreadsheet with the following columns (Table 4-4).

TABLE 4-4 Measuring Your Energy Use by Appliance

If you want to save time writing, use the free one we wrote just for you.6

Resource

My Energy (Microsoft Excel and Open Office Calc) bit.ly/myEnergy

It is not much more than the pad and paper type, but it lists many appliances, and automatically calculates the kilowatts and the cost to you based on the numbers you enter. We even provide help to modify it to add items. Who knows—perhaps you have a 3,200-watt amplifier for those exquisite karaoke nights. Add that to the list!

The next thing you need to do is have an Easter egg hunt inside and outside the home or building. That is, you walk around and find the energy labels for each appliance. You might want to start in one room, and then move on to the next. In addition, appliances can include certain electric-hungry items that are part of a whole house system, such as the central air (or HVAC), wall vacuum, speaker, and security systems.

Resources

If you prefer to do the calculations on your smart phone, there is the Energy Costs Calculator for Android phones and the Wattulator for the iPhone.7 They can calculate the approximate cost per year based on the watts and hours that you enter.

Wattulator

Energy Costs Calculator

When completed, you will have a fairly accurate calculation of energy usage for individual appliances. You will likely need to compare your total kilowatt-hours with your annual energy consumption from your energy bills. If there is a large discrepancy, either you didn’t do a good job estimating the hours of usage or you overlooked a few Easter eggs.

Option: 3 (Recommended) Get the Tools and DIY

We saved this option for last, because we reasoned that it is probably the best option. Why? Because it is less work, less money, easy to do, and provides more accurate results. By the way, we do not make a commission off these tools (unless you count “thank yous” as a commission, which we will accept), but we do provide a discount to some devices if you mention the book. Scan the QR code, make the call, mention the book, and you can get up to a 10 percent discount off some devices. You’re welcome.

Step 1: Buy an Energy Monitoring Device and Use It ($25–$120) A watt-hour meter—such as the Kill A Watt from P3 International (Figure 4-9)—is a little device that tells you how much electricity something uses, either at a given moment or over an extended period. Just plug the device into the meter, plug the meter into the wall, and read the display.8

FIGURE 4-9 The Kill A Watt is a handy device that can calculate the energy usage of a wide range of electronics or appliances. Brian Clark Howard.

One trick is to leave the meter and appliance connected for as long as you typically use the appliance: all day for a fridge, or an hour while a space heater warms a room, for example. If you provide your current electric rate per kilowatt, most of the devices predict how much you will spend today, in a month, and in a year. This is especially useful for finding the amount of kWh used in a month for devices that run intermittently everyday, like refrigerators. For seasonal equipment such as window unit air conditioners, just make sure you adjust the reading to compensate for the days it is not operational.

Measuring large appliances running on single-phase electricity (220 VAC), such as electric clothes dryers and most European appliances, requires a more versatile device, like the Watts up? from Electronic Educational Devices. This 240V meter ($100) comes with worldwide compatibility in the universal outlet version. Another option is the wireless e2 from Efergy Technologies.9 This device also comes in handy with appliances that aren’t plugged into an outlet (ceiling lights, water heater). There is a 10 percent discount from any of these manufacturers if you mention this book.

Resources

Kill A Watt (120 VAC/60 Hz) bit.ly/killAwatt

Watts up? (240 VAC/50 Hz) bit.ly/h8UVxQ

e2 (240 VAC/50 Hz) efergy.com

Power Pro (100-240 VAC/50-60 Hz) Prodigit.com

Step 2: Buy a Thermal Heat Loss Detector ($40) This handheld device finds leaks, which can be the source of higher heating and cooling bills. Not only does it detect temperature variances with its infrared laser, but some devices have a flashlight mechanism that changes color to blue (cool) when it identifies problem areas around drafty windows and doors, and uncovers hidden leaks and insulation “soft spots” (missing some fiberglass there?). When Kevin was a firefighter, those devices cost thousands of dollars. But this baby does the job for the price of a week of cafè macchiatos and newspapers. That is cheap labor!

Resources

Black & Decker bit.ly/bndthermal

Raytek MT6 bit.ly/raytekmt6

MasterCool MSC52224A bit.ly/mcthermaleak

Kintrex IRT0421 amzn.to/kintrekirt0421

Step 3 (Optional): Buy and Install a Whole-House Meter ($120) A whole-house meter tells you how much energy your dwelling is using at any given moment and how much you’ve used so far for the month—as well as how much it’s costing you. These meters start at around $120 and can be installed by an electrician if you’d prefer (it’s an easy, 15-minute job).

The Energy Detective and the e2 mentioned earlier both do whole house and individual monitoring. That would include monitoring your wind turbine energy generation as well. Another increasingly popular option is to monitor wind and solar electric generation from a personal computer or a smart phone.

Resources

The Energy Detective theenergydetective.com

Wattson diykyoto.com/uk

e2 bit.ly/efergye2

PowerCost Monitor powercostmonitor.com

Such monitoring can, therefore, be done from anywhere in the world. No, they aren’t spying on you! They are providing you access to information that you need. They can get this data from your smart meter, if you have one, or from devices like The Energy Detective. Check your availability at their website.

Special Note to New Building Owners Without Energy History

You are in luck, because there are tools that can help you estimate your energy use. For one thing, you can probably get some idea by looking at the average energy use of your current location. Start at www.EnergyStar.gov.

INTERCONNECT

Choosing to Stay Off the Grid in Vermont

A few years ago, Dale and Michelle Doucette decided to move their family into a new home in rural southern Vermont. The 22-acre property they settled on in Wilmington is wooded and gorgeous, and also not connected to the electrical grid. The Doucettes could have paid about $10,000 to run wires the quarter-mile to the grid, but instead they decided to become their own power plant.

According to USA Today, the Doucettes spent about $41,000 on a solar and wind hybrid system, with a shed full of 24 batteries and a backup propane generator. Their $500,000, 3,200-square foot house is built with efficient straw-bale insulation and lots of energy-saving features, like low-voltage lighting and high-efficiency appliances.

Dale is a wood carver who runs his saws on renewable energy, and Michelle is a chiropractor who works out of an office in their home. Their sons, 17 and 22 at the time of this writing, enjoy playing video games and watching TV, just like young people who live on the grid.

We gave Dale a call, and he told us he isn’t sure exactly how much energy his Bergey 1K wind turbine produces annually (Figure 4-10). “We use it strictly as extra charging for the batteries,” Dale told us. “It particularly comes in handy in the winter, when there’s no leaves and we get stronger wind, and when we’re using more energy, since days are shorter and lights are on longer.”

FIGURE 4-10 The Doucette family of Wilmington, Vermont, especially appreciates their 1 kW Bergey wind turbine in winter, when winds are strong and days of solar collection are short. Pictured is another Bergey (center) at New Life Evangelistic Center in New Bloomfield, Missouri. Rick Anderson/DOE/NREL.

Dale told us the turbine sits on an 80-foot, guyed tower. He said he did a lot of the installation work himself, though he hired some help as well. They didn’t use a crane, getting along fine with a gin pole and winch. “I’m a pretty hands-on guy,” he told us. “I have somewhat of an electrical background. And I like to know what’s going on; I’m buying the system, it’s my house, so I like to be informed.”

Dale told us that incentives from the state of Vermont covered about half the cost of the wind system. “I wish I could have gotten a bigger one, but money and time were not going to allow that,” he said.

Dale told us he is currently looking into adding a micro-hydro system on his property, since he has streams. “The object is to try and not have the generator running. We have two kids, and when they’re both home a lot of energy gets used,” Dale said.

We asked Dale what it has been like to live with a wind turbine, and he said it has worked great for five years, with only minimal maintenance. The only downside he could think of was that a “decorative nose cone has blown off a couple of times, so I don’t even bother with that anymore. It’s easy. They put it up, it spins, it makes power.”

We asked Dale if he had given a thought to bats or birds when he installed his turbine, and he said he hadn’t because he thought it was too small to make an impact. “The blades are only four feet long,” he said, although he pointed out that the spinning turbine seems to keep deer out of his garden at night. When asked about the potential for angry neighbors, he said his closest ones are three acres away, and that they never seem bothered. “The only time we hear any noise from it is when there are really strong winds, like above 50 miles per hour, and it is going really fast. It has a shutdown feature, and at times it sounds like an airplane shutting off,” said Dale.

When asked if he recommends small wind power to others, Dale said, “I recommend solar, hydro, wind. I recommend it all. We gotta make a stand here. Everybody takes power for granted.” As far as what we need to increase adoption, Dale said, “Ultimately, price is what’s the problem. Even my little generator was $5,000. In the society that we live in people aren’t willing to make that sacrifice. They want everything instantaneous.” For his part, Dale told USA Today he expected his system to pay for itself in about 20 years.

Dale’s advice to those considering a wind turbine is to do lots of research, measure how much power you need, get familiar with your surroundings, and then go look at other installed systems. He cautioned that it’s critical to make sure there is enough open space to support the tower (more on this later), and he stressed that it’s a good idea to get a second opinion. He also warns people to do their due diligence on service providers. “There are a lot of so-called experts in the field, with multiple opinions. A lot of people are inventors, but can they install it or run a business? That’s something you have to determine.”

The Doucettes are among the roughly 180,000 American families who live off the grid, according to Home Power magazine. Interestingly, that figure has increased about 33 percent a year for a decade or so, although the number of people who are hooking up small renewable energy systems to the grid is growing even faster. The number of on-grid systems in the United States is expected to eclipse off-grid applications within the next few years.

Boosting Your Building’s Energy Efficiency

Well, you got the results of your energy audit, and you have determined that some changes need to be made before you invest in a wind turbine.

Where to start: Cost evaluation. How much is it going to cost you? And what will be the annual savings and the payback period? Without further ado, Table 4-5.

TABLE 4-5 Common Improvements That Can Save Energy and Money

The table shows projected savings generated by audit-recommended improvements to an average single-family home up to 3,000 square feet, with annual energy (electric, water, and fuel) bills over $2,200. The cost and total savings will vary from home to home, but this gives you an idea for your typical Jones’ house. Finally, you can keep up with the Joneses by acquiring the stuff that pays you back in the long run.

First, let’s look for low-hanging fruit that requires little elbow grease or purchasing.

Adjust That Thermostat

On most systems, you can cut heating and cooling costs by an additional 20 percent by lowering the thermostat during the winter by 5 degrees Fahrenheit at night and 10 degrees Fahrenheit during the day when no one is home, or by raising it during air-conditioning season. You can do that with daily adjustments of a simple thermostat, but few of us are so diligent.

Instead, you could install a programmable thermostat (as low as $25) so that you can set it and forget it. Some utilities even provide them for you. According to the EPA, the average family will save $180 a year with a programmable thermostat, and new models are getting easier to use.

Even when you are home, also consider turning down the thermostat in winter, or turning it up in summer. When it’s cold, for every degree you lower the thermostat, you’ll save between 1 percent and 3 percent of your heating bill. You can also make like Jimmy Carter famously did in the 1970s, and don a sweater. A light long-sleeved sweater is generally worth about two degrees in added warmth, while a heavy sweater adds about four degrees, according to The Daily Green.

Use Cold Water

Heating water is the second-largest energy hog in the home, accounting for 12 percent of your energy use and costing the average household around $250 a year. Short of replacing the water heater with a more efficient one, building owners can save 5 percent on their utility bill by dropping the water temperature to 120 degrees from 130 degrees F and insulating the water pipes. Also consider washing your clothing in cold water—you can save $60 a year.

Power Up! Put your hand on your hot water heater. If it’s cool, your unit is well insulated. If it’s warm, cover it with a water heater jacket, available at hardware stores and home centers for a few dollars.

Also consider taking shorter showers, because the more hot water you use, the more you have to pay to heat it up. According to the EPA, the average shower uses 25 gallons of water. Restrict yourself to only five minutes and you’ll halve that.

Use Electricity When the Rate Is Lower

Some power authorities have varying price rates (called time-of-use, critical peak, or dynamic pricing), depending on the supply and demand for your region. Some rates may change by the hour, especially for large businesses. Check with your power provider for their policies. In many places, electric rates are cheaper at night, because demand is so much less (Figure 4-11).

FIGURE 4-11 The first step before installing any renewable energy systems is reducing your energy use through efficiency. Brian Clark Howard.

Taking advantage of lower rates could require only small changes in lifestyle, like placing your clothes in the dryer in the evening. But if the rates vary hour to hour, you might be left guessing. There are smart phone applications that do the thinking for you, such as Power Stoplight Mobile by Smart Power Devices.

With the program, you see a stoplight prompt on your screen that lets you know the best time to run major electrical loads, based on dynamic pricing. For those with renewable energy systems, a blue light indicates optimal times for net metering. The guessing is gone. As soon as you see the green light, wash those dishes. Currently, this app works in many U.S. states and Toronto, Canada. It is available on the Android, Blackberry, iPhone, iPod Touch, and iPad (cost: $0.99).11 Again, we receive no commission, just thank yous.

Resource

Power Stoplight Mobile app powerstoplight.com

In addition to such mobile apps, whole-house energy monitoring systems often have the same functionality built right in. Some utilities have also been testing pilot programs that distribute little plastic globes to elect customers. When the orb is green, the rates are lower, and the user might choose to run high electric loads, such as washing machines. If the globe glows red, that indicates higher pricing. Studies show that such active feedback encourages consumers to save energy and money, while making them feel more empowered and connected to energy use.

Now that you have taken these easy steps, you can afford to spend a little money for some significant cost savings.

Plug the Leaks

Get some caulking and fill in all gaps, cracks, and joints of windows, doors, skylights, and trim. Operating heating and cooling systems accounts for 46 percent of the average home’s utility bill (more in cold climates), according to the U.S. Department of Energy. Yet drafts sap 5 to 30 percent of that energy.

For the best return on your energy-conservation effort, start by making sure all windows and doors have good weather stripping. If you have an attic, make sure there’s sealant around pipes, chimneys, ductwork, or anything else that comes through the attic floor. Sealing those leaks is cheap and easy and can save 10 percent, or $190 per year, for the average home.12

Install Ceiling Fans

The annual savings in Figure 4-10 are based on one energy-efficient fan that is used only when the room is occupied. If you have more rooms and more fans, you can multiply the savings. Ceiling fans lower perceived temperature in summer, lessening reliance on air conditioning and saving energy. In winter, reversing the direction of fans draws warm air down from the ceiling, saving up to 10 percent on heating costs. In general, counterclockwise rotation produces cooling breezes while switching to clockwise makes it warmer. When you are fan shopping, be sure to look for Energy Star–certified models, and get one that has a reversible direction.

Resource

Energy Star Ceiling Fans 1.usa.gov/es_fans

Install Compact Fluorescent Light (CFL) Bulbs (or LEDs)

The annual savings in the energy savings chart are based on 40 bulbs illuminated for three hours each day, the average U.S. residential usage. Light in all buildings accounts for about 30 percent of the energy consumed in structures.13 With proper use, CFLs should last up to about 10 times longer than traditional bulbs, so you will be making that savings for at least five years. Each CFL that replaces an incandescent bulb should save $30 over its lifetime (Figure 4-12).

FIGURE 4-12 CFLs now come in many shapes and sizes, and they will help you save energy. If you don’t like them, opt for halogens and dimmer switches or LEDs. Brian Clark Howard.

Go further and save even more energy with light-emitting diodes (LEDs), which are becoming much more widely available, for prices that are more competitive. LEDs can last up to hundreds of thousands of hours, and use up to 90 percent less energy than incandescents. They are also showing rapid advancements in color and dimmability, and are falling in price. A good LED replacement for a 60-watt incandescent can be picked up for $20 at Home Depot.

If you don’t like CFLs and can’t afford LEDs yet, get some halogens and dimmer switches. Halogens are up to 40 percent more efficient than standard incandescents and they last two to three times longer. Plus, the more you dim your lights, the more energy you save. Get occupancy and motion sensors to make saving even easier.

Learn a lot more about efficient illumination in the book Green Lighting (McGraw-Hill, 2010), part of this same series.

Install a Tankless Water Heater

Traditional water heaters end up wasting quite a bit of energy, because they preheat a large volume of water in the tank, even if you don’t use it for a long time. This means heat is slowly leaking out. Plus, if you have guests over who all want to take showers, you may “run out” of hot water from the tank.

A tankless water heater, in contrast, solves both these problems by heating water only as it is needed, “on demand.” Tankless water heaters can use electrical elements or natural gas burners to heat a stream of water, with both types having their advantages and disadvantages.

A seven gallons-per-minute (gpm) tankless heater can supply two or three major applications (shower, dishwasher, kitchen sink) at the same time. Tankless water heaters are also space saving and they tend to last longer than conventional heaters. They cost more up front, but they will save money over time.

Boost Insulation

Estimates on the cost and savings of boosting insulation vary widely depending upon locality and product used, but for homes with barely any, adding insulation makes a significant performance difference (Figure 4-13). This is especially true with central air systems because lots of air can be lost to the outside or unused basement, particularly at corners and joints. Insulate ducts wherever possible. If you have an infrared thermal device, you will know if you have done the job well.

FIGURE 4-13 Spraying insulation into your attic and behind walls can significantly reduce your heating and cooling bills. Community Services Consortium/DOE/NREL.

Install Storm Windows

The annual savings for adding storm windows to an average building, with 25 windows, is close to $700. Storm windows cost an average of $100 to $200 each and have a typical payback period of four to seven years. There is an easy way to select your windows based on your location, thanks to EnergyStar.gov specifications, which are included in the footnotes.14

Get an Energy-Saving Refrigerator

The Energy Star Program website can guide you to hundreds of selections of energy-efficient refrigerators. One of us recently bought a dented unit and didn’t have to pay full retail (score!). We received a rebate, and started getting annual savings.

In fact, a good rule of thumb is to make sure any new appliance meets Energy Star standards or EU standards. A home that uses Energy Star products can save a significant amount of electricity and money each year compared with a home that doesn’t.

Additional Energy Savers

There’s no shortage of ways to save money on home energy costs. For more suggestions, go to your local or national energy efficiency office. We have provided a few.

Resources

Energy Star energystar.gov

Office of Energy Efficiency bit.ly/ca_oee

European Union Energy energy.eu

Bureau of Energy Efficiency bee-india.nic.in

You can also opt for consumer websites like The Daily Green (www.thedailygreen.com) and Earth911.com.

Here are a few additional ideas.

Give Your HVAC Equipment an Annual Tune-Up

Just as cars need regular maintenance, so does heating and cooling equipment. By keeping your system clean and in good working order, you can save an average of 5 percent on your bills and extend the life of your investment. Many utilities offer free or low-cost annual inspections if you call during the off season.

Change Filters Regularly

Dirty filters can restrict airflow and make your furnace work harder, so it’s a good idea to change filters once a month during the heating season. If you get tired of that, consider investing in a permanent electrostatic filter. Not only does this reduce maintenance, but you’ll also zap up to 88 percent of debris, compared with 10 to 40 percent for disposable filters. Plus, electrostatic filters are much better at controlling bacteria, mold, viruses, and pollen.

Put Up Window Plastic

If you can’t afford storm doors and windows, or if they are old and leaky, consider putting up some thermal window plastic during the cold months. Don’t worry—when installed properly it is virtually invisible, but it provides an extra layer of insulation by trapping still air.

Do it Now, While Incentives Last

Government incentives change all the time, but chances are good that you have something available to help you make efficiency improvements to your home or business. Energy efficiency is good for homeowners, local businesses that provide improvements, and the environment, so incentive programs are often politically popular.

Only a few years ago, we had to send in receipts to get power authority rebates that were sponsored by the government. But since energy infrastructure has come into the limelight, it seems many governments provide an increasing array of incentives. Many programs also target low-income homeowners with additional incentives.

The American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009 provided a credit worth 30 percent of the cost of materials for a broad range of improvements, such as energy-efficient windows and insulation, up to $1,500. Unfortunately, as of this writing, that credit expired at the end of 2010. However, some renewable-energy systems, including solar panels, wind turbines, and geothermal systems, still qualify for a 30 percent tax credit on parts and labor through 2016. So if you are inclined to make an upgrade to your home, now is the time to do it, or to set money aside to do it before the credits expire.

Summary

You may have started this book thinking that all you needed for a wind system was a turbine, some wire, and a stiff breeze (Figure 4-14). But we hope you have an idea now that it’s worthwhile to take a step back and look at the complete picture of how you use energy, and how you can use it smarter. If you spend a little bit of time and money improving your home or business, you can save 20 to 60 percent off your electric bill.

FIGURE 4-14 A wind turbine is an iconic image that has captured the spirit of hope around the world. But before you take the plunge and buy a system, make sure you are saving as much energy as possible. Brian Clark Howard.

That means you can install a cheaper renewable energy system, if you choose to go that route. Richard Perez, the founder of Home Power magazine, wisely said, “Every $1 spent on energy efficiency saves at least $3 in renewable energy system costs.” But whether you end up investing in a wind generator or not, these first steps toward energy efficiency are likely to yield the best return on investment.