1

Discover Your Brown Shorts

We now know that attitude, not skill, defines high and low performance. But while attitudes like coachability, emotional intelligence, motivation, and temperament are all nice to have, they’re far from a one-size-fits-all solution. An employee who is competitive and individualistic may be the perfect fit for a solo-hunter commission-driven sales force or a Wall Street financial firm. But put that same personality to work in a collaborative, team-loving start-up culture with a bunch of programmers all coding around one big communal desk, and that individualistic superstar is doomed to fail.

The “right” attitude is as unique as the organization to which it belongs. Just as we learned on “Sesame Street” all those years ago, we’re all different, and we’re all special. These unique attitudes are what make your organization so special, and that is what Hiring for Attitude is all about. This chapter will guide you through a Brown Shorts Discovery so you can clearly identify and document those key attitudes. (Brown Shorts is a crazy name, I know, but I’ll explain it momentarily.) Now, you may be tempted to say, “I know what makes my company so special,” and jump ahead, but as the following story shows, that’s a dangerous thing to do.

Jim is the vice president of nursing for a small community hospital. He shared the following story about a hiring error he made before he became certified in Hiring for Attitude and learned about his Brown Shorts. When a résumé from a top nurse (I’ll call her Sue) looking to relocate from a well-known East Coast teaching hospital landed on Jim’s desk, he eagerly scheduled an interview. Jim’s initial impression of Sue was that she was highly professional. (It was only later that he admitted he was also thinking things like: “stiff,” “formal,” and “not like the rest of our nurses.”) During the interview, Sue spoke at length of her love of analytical thinking and her eagerness to learn the latest cutting-edge techniques. “Technical perfection,” she said, “is always my first priority.” When Jim asked Sue to name her most admirable strength, she said, “My ability to stay tough, even when engaged in heated and complex debates with world-class clinicians.”

Excited (and he now admits somewhat wowed) by Sue’s level of skill and experience, Jim hired her. And he did so without considering how Sue’s analytical and hard-as-nails attitude might fit in with the warm, friendly, and eager-to-serve culture at his small community hospital. “She’d been a top performer at her last job in every way possible,” Jim said. “So I figured there was no way I could go wrong.”

Not long after Sue came on board, Jim noticed that things with his staff and the patients weren’t going as well as usual. And most of the upsets were Sue related. Some of her peers saw Sue’s love of “heated and complex debates” as unreasonable arguing or even arrogance, and they started coming up with excuses to avoid working with her. Others felt attacked by Sue’s seemingly sharp words and responded with anger, defensiveness, and blame. Jim watched as the loyal sense of teamwork that was one of the hospital’s greatest strengths began to be replaced by avoidance, taking sides, and even outright conflict. And that negativity began to register in patient complaints and surveys.

Sue didn’t lack skills; she lacked the right attitude—something that’s far more difficult to identify. But when he interviewed Sue, Jim had been unable to predict her lack of attitude because he didn’t have his Brown Shorts (and his Brown Shorts Interview Questions and Answer Guidelines). And while he did figure it out after Sue came on board, Jim couldn’t make things better, no matter how hard he tried. Even when people are willing to change (which is not the norm), it’s not easy to fix attitude. Sue was used to being seen as a superstar—not as a problem. So she saw no reason, and felt no incentive, to change her attitude as Jim was coaching her to do.

Jim hired someone else’s superstar without stopping to consider whether her attitude would make her a superstar in his organization’s culture. “I couldn’t believe how just one person with the wrong attitude could cause this much trouble,” Jim said. Of course, this entire situation could easily have been avoided. Jim simply needed to identify the right attitude for his organization and then use that deeper understanding of attitude as his primary measure for hiring the right talent—a process I call “discovering your Brown Shorts.”

WHAT THE HECK ARE “BROWN SHORTS”?

I know Brown Shorts is a pretty bizarre name, especially for an ostensibly serious management topic. So I’m going to define the term, tell you where it came from, and then explain what it means for you. But be forewarned. In the next few paragraphs I’m going to talk about Southwest Airlines, and I’m going to brag on them a bit (as we say down South). And no, this isn’t one of those company lovefest type of books, where I spend 200 pages gushing over a few companies. Yes, Southwest is a great organization, but this just so happens to be a great story. And even though you’ve probably read a lot about Southwest, there’s a very good chance you haven’t heard this story.

Southwest Airlines understands its own winning attitude and does a great job of hiring for it. You have to fly Southwest only once to experience the organization’s famous attitude of fun. The gate agents might initiate a game of “who has the biggest hole in your sock?” to make waiting for a delayed flight a bit less stressful. Or perhaps the crew sings the seat belt instructions. I even read about a Southwest pilot who walked past a gate of waiting passengers with a Dummies guide to flying poking out of his briefcase. When you fly Southwest, you notice that every employee—from executives to pilots to flight attendants—lives the core value of fun. But not all fun is alike. Southwest wants a certain kind of fun, a specific attitude, and to find that attitude. they have come up with some clever and unconventional tools to help assess whether or not a candidate has that attitude. This is where the Brown Shorts come in.

A former Southwest executive once told me a story about a group interview of potential pilots. To give a little background on pilots, you need to know that many of them are male, over 40, and ex-military. They have a fairly serious demeanor that shows in everything they do, including how they dress. So these candidates were conscientiously attired in their black suits, white shirts, black ties, black over-the-calf socks, and spit-polished black shoes. They were all ushered into a typically bland meeting room where everybody sat down and waited for the usual drill. But then the Southwest interviewer came along and said, “Welcome! And thanks for coming to Southwest Airlines! We want y’all to be comfortable today, so would anybody like to change out of their suit pants and put on these brown shorts I’ve got here?”

Let’s pause for a second. To get the full impact of this, you have to remember that this is a job interview. You know—a hyper-formal affair in a sparse meeting room that follows a standard script where you talk about all the great things you did at your last job and why you want this new job. That’s it. No getting undressed and putting on shorts, or anything crazy like that.

Understandably, a good number of the pilots were taken aback. They gave the Southwest interviewer a look that I imagine conveyed the universal unspoken question: “Are you smoking something?” I know if I’d been in that group, I’d have been thinking, “Listen, buddy, I’m all dressed up in my best black suit, white shirt, black tie, black over-the-calf dress socks, and spit-polished black shoes, and now you want me to change into some ugly brown shorts? I’m going to look like an idiot! Find some other chump to look like a fool.”

Naturally, the pilots weren’t that openly honest (or rude). It was, after all, an interview. The ones who declined the shorts simply said, “Thanks, but no thanks.” And because Southwest is so serious about having fun, the interviewer in turn said, “Thanks, but no thanks” to the pilots who didn’t don the shorts. Herb Kelleher, founder and now chairman emeritus of Southwest Airlines, wasn’t kidding when he said, “If you don’t have a great attitude we don’t want you.” The pilot could have been an instructor at Top Gun, but if the brown shorts were a no go, then that person wasn’t going to fly for Southwest. (See Figure 1.1.)

Figure 1.1. The Brown Shorts Guys

Southwest is serious about finding people who are fun. And that’s not just because the organization is so nice (although it really is). Southwest also recruits for people who are fun because it helps the airline’s bottom line. Fun is Southwest’s competitive advantage and how the organization gains customer loyalty and ensures repeat business. Fun is also how Southwest loads planes quickly and why customers don’t mind the lack of seat assignments. Reading this you may think fun is a nice add-on to smart operational management. But it is actually the secret sauce that enables Southwest to successfully execute all those operational innovations. (The other carriers know the same tricks that Southwest does, but because they don’t have enough people with the right attitude, they can’t successfully execute them.)

Furthermore, every employee at Southwest controls the brand marketing. Let’s say the average pilot flies 75 hours per month, and that the average flight is roughly two hours long. That comes to about 38 flights per month per pilot. If a typical Boeing 737 holds about 140 passengers and flies about 75 percent full, that’s about 105 passengers per flight. If you then multiply that by the roughly 38 flights each pilot flies per month, you get just under 4,000 passengers (customers) a month with whom a Southwest pilot might interact. Let me repeat that. With just my back-of-the-envelope calculations, I guesstimate that each Southwest pilot interacts with—and profoundly influences—about 4,000 customers per month. That’s a whole lot of customers who could be lost if Southwest hired a pilot with a bad attitude, somebody who didn’t fully represent the Southwest brand. I don’t care how many billboards you rent and television spots you buy, all the marketing in the world can’t help you if your employees are undermining your brand every day.

You’re probably wondering about the candidates who did put on the shorts. Well, they made it to the second round of the interviewing process. You need to do more than put on shorts to work at Southwest, but it’s certainly a good start that will get you in the door.

Over the years, I’ve talked to many Southwest executives (both current and former). And some of them had a slightly different version of this story. I’ve heard that the shorts weren’t actually brown but rather Jams shorts—those funky, brightly colored surf shorts popular in the 1960s and 1980s. (Yes, I owned a few pair.) Apparently in one interview session every candidate walked down to the Southwest store together where they all donned the shorts. I’ve also talked to a bunch of pilots who said they wore the shorts or had a friend who did.

Whatever the exact truth of the brown (or multicolored) shorts, this story inspired me. And after the first time I heard it, the Brown Shorts concept began to grow in my mind. It seemed to me that every organization should have a similar test of attitude—something as simple and effective as a pair of brown shorts—by which to assess which candidates have the “right” attitude and which ones have the “wrong” attitude. Sure, Brown Shorts is a funny and weird way to describe that idea, but that’s what makes the label so memorable.

I’m not suggesting that every company start asking its job applicants to drop their pants. It wouldn’t work, and your lawyers (and mine) wouldn’t like it. And I’m not telling you to emulate Southwest’s let’s-have-fun attitude. Fun may work for Southwest, but if your organization is a hospital or a nuclear power plant, fun probably isn’t the key attitude you’re after. It’s not Southwest’s culture I want you to mimic but rather its Brown Shorts approach to hiring for attitude.

Southwest understands the attitudes that make the organization so successful, and they’re dedicated to hiring only the people who truly live and breathe those core values. In 2010, Southwest received 143,143 résumés and hired 2,188 new employees. Obviously, the airline doesn’t take just anybody. James Parker, one of its past CEOs, said in a BusinessWeek interview about Southwest’s hiring practices “If you’re hiring a pilot or a mechanic, a lawyer or an accountant, you want people with a high level of skill. But what we really looked for was people who had the right attitudes, who were ‘other-oriented,’ who were not self-absorbed, who wanted to accomplish something they could be proud of.” When the interviewer intelligently asked how you can tell if someone is “other-oriented,” James responded, “I always used to see if they had a sense of humor—I think that’s very important.”

It’s easy to look at the stock market and say, “Wow, Southwest is successful.” But when you examine the measures that make Southwest one of the most successful airlines in the United States, you can see its commitment to attitude at work. For instance, Southwest:

• Has consistently received the lowest ratio of complaints per passengers boarded (out of the nation’s 16 largest airlines) over the 23 years the DOT has been tracking customer satisfaction

• Was ranked number two on Glass Door’s U.S. 2011 list of Best Places to Work. (Southwest rated a 4.4 out of a possible 5 compared to Facebook, who took the number-one spot with a 4.6.)

• Has for the last 17 years been rated Number One among all airlines by the American Customer Satisfaction Index

• Was recognized as a Top Employer in G.I. Job’s 2011 list of Top Military Friendly Employers

This list barely scratches the surface of the recognitions Southwest receives every year. You can’t fail to notice that Southwest’s loyal customers (it carried 88 million passengers in 2010) love the airline. Southwest’s 35,000 employees love working for Southwest. And it seems safe to say that the shareholders are probably pretty enamored with the organization too.

Southwest has consistently maintained this widespread feeling of love (LUV in Southwest lingo), and it’s preserved that love through some challenging times for airlines (like 9/11 and subsequent huge economic downturns in the travel industry). And the driver behind the airline’s phenomenal level of success is, without a doubt, attitude.

One final note before I tell you how to find your Brown Shorts. Don’t make the mistake of thinking attitude applies to Southwest because it’s in the service industry. Throughout this book you’ll read about organizations ranging from Google to Pixar to the local community hospital that have discovered how to make attitude a major competitive advantage. If attitude is a critical component for a group like the Navy SEALs, it’s probably good enough for the rest of us.

ARE BROWN SHORTS ACTUALLY SHORTS?

I shared this Southwest story because I want you to understand the origin of the Brown Shorts concept. Some organizations are serious about hiring for attitude, which drives amazing business success. But I don’t want you to get the wrong idea about what your Brown Shorts should look like or how you should develop them.

I’ve never been a fan of business books that oversimplify things. You know, where the author leads you to believe that you can be just like Company XYZ if only you too find your magic one-word solution. Your Brown Shorts are not going to be brown, and they are not going to be shorts. And they are not going to come wrapped in a single-word package like “fun” or even “sense of humor.” (Even at Southwest, Brown Shorts are a lot more detailed and comprehensive than just “fun.”)

The goal is not to adopt Southwest’s culture. First, your culture is unique and special. It’s totally different from South-west’s, which is the way it’s supposed to be. But like Southwest, you want to clearly identify the attitudes that make your organization great so you can do a better job of hiring stars who share that special attitude. Second, you’re not going to get your Brown Shorts down to one word, like fun. Southwest summarizes its Brown Shorts with elegant simplicity, but the executives have years of detailed work, mountains of validation, and hard data about the people who will and will not succeed. The elegantly simple one-word solution for your business will come in time. But right now I’m going to show you how to get a deeper insight that will make everything else possible.

In a nutshell, your Brown Shorts are the unique attitudinal characteristics that make your company different from all others. They are a list of the key attitudes that define your best people, but they also describe the characteristics of the people who aren’t making it. When you ask your candidates to “wear” your Brown Shorts, you’re going to learn a lot from how they respond. If someone is happy to wear your Brown Shorts, it shows they have potential to be a high performer. More important, your Brown Shorts reveal the people you shouldn’t consider hiring. And I think it’s important to repeat that last concept because it trips up a lot of people. Your Brown Shorts don’t just tell you whom you should hire; they also identify whom you shouldn’t hire.

My company, Leadership IQ, tracked 20,000 new hires over a three-year period. We found that 46 percent of new hires failed in one way or another, 35 percent became middle performers, and only 19 percent went on to become legitimate high performers. Rounding these numbers a bit, I find that for every 10 people I hire, about 5 will fail, 3 will do OK, and 2 will be great. But now imagine you could eliminate the 5 who fail and keep the other ratios the same. So for every 10 people you hire, 6 will do OK and 4 will be great.

So if the only change you made was to avoid hiring the people who are likely to fail, you’d have twice as many high performers. Imagine the monumental successes you’d be racking up with twice as many high performers! You’d have fewer headaches without those failed hires walking around your organization. People with the wrong attitude are tough to manage; they consume tremendous amounts of management time and distract you from more value-adding activities. They also irritate and chase away a lot of high performers and contribute to a host of negative occurrences.

So while you do want to focus on attracting and hiring more high performers, I hope I’m making the case here that you also need to focus on not hiring the people who are a poor fit for your culture. The Brown Shorts Discovery begins with recognizing these poor-fit folks.

THE PEOPLE YOU SHOULDN’T HIRE

There are two basic categories of people that you shouldn’t hire:

• People whose attitudes just don’t fit your culture

• People who have problem attitudes

Now, there’s nothing inherently problematic with the people whose attitudes just don’t fit your culture. They’re good people; they’re just not good for you. In the dating world we’d say, “It’s not you, it’s me.” Just because you don’t want to don a pair of brown shorts doesn’t mean you’re a bad pilot—you’re just a poor cultural fit for Southwest. Not wanting to wear brown shorts doesn’t preclude you from being the best pilot ever at Delta or United or American or someplace where you’re going to be a better cultural fit. Someone who’s a great fit at Southwest Airlines might not be the perfect fit at The Four Seasons Hotels. Both companies are fantastic, but they serve very different customers in very different ways. Google and Apple are both cranking out great products, but they sure do it differently. A star at one company might be an uncomfortable fit somewhere else. There are no universal high performers, only the high performers who are right for your organization.

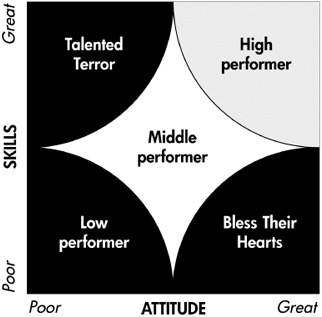

However, the other category of folks that you shouldn’t hire—the ones who have issues when it comes to attitude—is a totally different story. Many organizations acknowledge only high, middle, and low performers. High performers are viewed as being desirable to hire while low performers are the people those organizations do not want to hire. High, middle, and low performers certainly exist, but there are actually a few different types of low performers, and some are harder to discern in an interview than others.

Think of performance as having two dimensions: skills and attitude. (You can undoubtedly come up with others, but our numerous studies show that almost all attributes of low performance ultimately get subsumed by skills or attitude.) The general rule of thumb is people who are incompetent and unpleasant can usually be safely classified as low performers. (They have lousy skills and bad attitudes.) These folks are pretty easily identified in the interview process and are not a giant problem for hiring managers.

But hiring isn’t always that cut and dry. Some people have great attitudes but terrible skills. Others have stellar skills but bad attitudes. These examples illustrate two very different categories of performance, but both can be considered low performers. You don’t want to make the mistake of hiring either of them.

We call the people who have great attitudes but lousy skills the Bless Their Hearts. To translate for anyone who hasn’t spent much time in the Deep South, “bless your heart” is a Southern phrase that basically means “Thanks for trying, but what you just did was totally clueless. And you’re lucky my code of Southern gentility prohibits me from saying anything more, because I might just slip and say something’ really mean.” While I currently live in the South, I grew up in the North where we instead used the phrase “God love ’em,” when what we really meant was “I’m sure they meant well, but boy, that was dumb.” (The expression of choice for my buddies in New York is “that poor bastard.”)

Regardless of the phrase, if you’re using it to describe someone in your organization or someone you’re interviewing, it’s time to rethink that person’s performance potential. Someone with a great attitude (trying hard and genuinely wanting to please) who repeatedly fails to get the job done right (doesn’t have the skills) isn’t an “almost” high performer. God love ’em, but that person is a low performer, and no amount of amazing attitude is going to make up for it. And no low performer should be admitted to the elite club that is your organization.

You can root for that individual every step of the way (everyone wants to see a plucky underdog succeed), but that doesn’t change the low performing facts. Sure, Southwest pilots need to be fun, and they have to want to wear the shorts. But before they can even get to that point, they actually have to show that they are excellent at skill-related tasks such as flying and landing a plane. With the tools this book provides, you’ll be able to easily zero in on the Bless Their Hearts during the hiring process. As I said at the beginning of this book, compared to attitude, skills (or a lack thereof) are pretty simple to identify.

Talented Terrors

The other category of low performer is the exact opposite of the Bless Their Hearts. These folks have great skills but lousy attitudes. We call them Talented Terrors. When they’re at their worst, these people are like emotional vampires. And while they won’t actually suck your blood, the frustration of dealing with them will suck the life out of you.

Talented Terrors are by far the most difficult kind of low performer to detect in interviews. By definition, they’re highly skilled, so lots of hiring managers get lulled into complacency during the interview because “nobody this skilled could possibly be a poor fit, right?” Talented Terrors are also very smart. They are masters at turning on and off some of their more troubling attitudinal problems. Think about the Talented Terrors you already employ. No matter how bad they’re acting on a given day, if your Chairman of the Board walks by their desk, they will be full of sunshine and buttercups. “Hello, Sir, wonderful day we’re having! You’re looking more fit than ever. Have you lost weight? I just finished reading your letter to the shareholders, and it was brilliant as always, Sir!” Of course, as soon as the Chairman leaves, the sunshine gets replaced by dark and threatening clouds and the Talented Terrors return to biting everyone else’s heads off.

Another thing that makes Talented Terrors so difficult to detect is that they usually aren’t all bad. That is, they’re not without some good qualities. (If they had zero redeeming qualities, they’d be quite easy to detect and dismiss.) In the real world, things are seldom totally black and white, and Talented Terrors are no different. They’re (usually) not monsters; they’re people who have traits that seem just fine mixed with a few traits and characteristics that will drive you so nuts that you may regret becoming a manager. See Figure 1.2 for a schematic of how all these performers and traits fit together.

Figure 1.2. Performance Breakdown

THE FEW BROWN SHORTS CHARACTERISTICS THAT MATTER

Only a few characteristics earn someone the label “do not hire.” Look at all the poor fits currently in your organization and you’ll typically find that only a handful of characteristics separate them from your middle or high performers. For instance, take your Talented Terrors. I’ll bet you have a few who would be high performers if only they weren’t so negative, so quick to blame others, so resistant to change, so in need of personal recognition. They have plenty of desirable traits and just a few attitudinal issues (major though they may be) holding them back.

Don’t get me wrong. You can’t magically excise those unappealing traits and turn the Talented Terrors into the employees of your attitudinal dreams any more than you can take the Bless Their Hearts and imbue them with the skills you want. The thing to note here is that there are a limited number of characteristics that appear again and again among your poor fits. The same holds true when you think about the high performers who fit seamlessly in your culture. They’re not better than your middle performers in every possible way, but there are a few important characteristics that set them apart. They might be more proactive, more team-first, more willing to look at the bigger picture, or more pragmatic.

Discovering Differential Characteristics

The key here is to think about differential characteristics—the attitudes that separate your high performers from your middle performers and your low performers from everybody else. You don’t want a giant list of every possible characteristic under the sun; you just want the important critical predictors of employee success or failure for your organization.

In theory, this shouldn’t be that complicated, but things sometimes get off track—such as when somebody downloads a big list of great attitudes from the Internet. She reads about all these great characteristics people should have: honesty, integrity, emotional intelligence, work ethic, positive attitude, loyalty, values, mission focus, innovation, teamwork, persuasion, effective communication, and so on. She then passes the list around to all the hiring managers and says, “Please choose the characteristics that you think are most important for our employees to have.” The managers look at the list and pick everything. Seriously, if your HR department or senior executives asked you to pick from a list of important characteristics, wouldn’t you choose integrity, honesty, and values? I wouldn’t want to be the lone person who picks everything except those, leading to questions like “Gee, Mark is smart but is he an unethical sociopath?” And it’s not as though you can leave teamwork, work ethic, or positive attitude off the list. Observe, here, that when everything is important, nothing is important.

This big list of wonderful traits everyone should have doesn’t explain why people succeed or fail. Look again at the list of characteristics referenced here: integrity, honesty, values, teamwork, work ethic, and positive attitude. Not all of these are going to be equally important to your organization. For example, before I started Leadership IQ, I was an executive for another company. During a transition, I took over a division and suddenly was in charge of a bunch of managers I did not personally hire. Some were great, some were satisfactory, and a few weren’t cutting it. But one manager in particular drove me nuts.

This man wasn’t evil or malicious. In fact, he had integrity, honesty, values, teamwork, and work ethic. However, what he did not have was a positive attitude. I surely have a skeptical streak, but this guy made me look like Mary Poppins. He could find the gray cloud surrounding any silver lining—anything I said was immediately met with a list of reasons why it wouldn’t work.

This guy didn’t last very long, but that’s not my point. Discovering your Brown Shorts is not about making a list of all the characteristics that sound desirable or all the traits you wish you had. This is an exercise in realism, not idealism. You need to know which characteristics predict failure in your organization, so you can avoid hiring anyone that shares those traits, and which predict success, so you can recruit and hire more folks who have those characteristics.

In the end, you will have a list of three to seven Positive Brown Shorts (characteristics that differentiate high from middle performers) and three to seven Negative Brown Shorts (characteristics that differentiate low performers from everyone else). It’s this short list of key attitudes that will direct how you create your Brown Shorts Interview Questions and Answer Guidelines. First, though, you need to complete the Brown Shorts Discovery Phase and find out exactly what your Brown Shorts are.

Finding Your Brown Shorts

If we had perfect data from performance appraisals, we likely wouldn’t have to dig any further to understand our Brown Shorts. If the only people who received high ratings were people with both great skills and great attitudes, we’d know exactly what they were doing and what differentiated them from everybody else. Unfortunately, attitudes are seriously underrepresented on performance reviews, and we all know plenty of people getting top reviews who didn’t really deliver top performance.

If we had perfect performance appraisal data, we’d know exactly which people were struggling or failing in their jobs, why it was happening, what attitudinal problems were most prevalent, and which ones were least correctable. We’d also know whether these problems were systemic or specific to certain individuals. Again, this kind of accurate and specific data is not typically readily available. (Although, believe me, we scrub our clients’ data pretty hard to glean whatever insights are lurking in there.) But don’t get too disheartened because the final chapter will show you how to turn your Brown Shorts into a performance management tool called Word Pictures that will help solve these problems.

For now we need some insight into the issues I just discussed. And that requires interviews with a few of the folks who are living your culture and regularly interacting with both your high and low performers. This type of interviewing is best started at the top (the CEO if possible) and continued step-by-step deeper into the organization.

What to ask can be as simple as “In your experience, what separates our great attitude people from everyone else in the organization?” If you get a great response to that question, then you’re on a roll. But you’re going to find that some people struggle with these big, broad questions. It’s difficult to supply a thoughtful and well-synthesized answer to such a grand question. I recommend instead starting with something much more specific, such as “Think of someone in the organization who truly represents our culture. This would be our poster child for having the right attitude for our organization. Could you tell me about a time he or she did something that exemplifies having the right attitude? It could be something big or small, but it should be something that made an impression on you.”

The goal is not to be answered with generalities; you want specific nitty-gritty detail and you want it fast, so push for details. You may have to ask this question multiple times—following up each time with the question “Could you tell me about another example?”

When you’ve exhausted that line of questioning, start on the inverse version. Try something like “Without naming names, think of someone who works (or worked) in the organization who did not represent the culture. This would be our poster child for having the wrong attitude for this organization. Could you tell me about a time this person did something that exemplifies having the wrong attitude? It could be something big or small, but it should be something that made an impression on you.”

Again, this detailed question elicits specific examples. And this is probably a good time to introduce the concept of Behavioral Specificity, which I’ll refer to a number of times in this book. One of the diseases I see afflicting many organizations is what I call “fuzzy language disease.” This disorder causes people to describe situations so vaguely that no one else knows what they’re talking about. It’s especially bad when trying to verbally distinguish between high and low performers. And when you start interviewing and surveying people to understand the differences between high and low performers, you are going to hear fuzzy language disease all over the place.

For example, imagine you’re interviewing one of your executives about the differences between people who aren’t meeting expectations (low performers) and those who go above and beyond meeting expectations (high performers). The executive first says that “people who meet expectations tend to treat everyone in a courteous manner.” Now maybe this isn’t a great example, because you know exactly what courtesy means, right? I know I do. Courtesy means that men hold open doors for women, and when sitting in a restaurant, a man always gives the woman the best view. Usually this translates to giving the woman the chair with her back to the wall so she can look out onto the rest of the restaurant while the man gallantly gazes only at her. And if the woman leaves the table for any reason, the man naturally stands up when she does. (There are days when the modern world feels overwhelming, but stick me in 18th century Vienna and I’m good to go.)

Now wait a minute—please don’t tell me your definition of courtesy didn’t match precisely with mine. I thought everyone defined courtesy as the thing with the chair and standing up. No? OK, let’s try a different scenario. Imagine the executive says that people who meet expectations “maintain the highest standards of professionalism.” This one is easy. Professionalism means that employees should always say “Thank you for your time” whenever they finish an interaction with the boss. (Think back to the television show “The West Wing” when all the lesser characters would say, “Thank you, Mr. President” whenever they left the Oval Office. Now that’s professionalism.)

Oh, come on now. Don’t tell me that you thought professionalism meant not showing up to work with flip-flops and nose rings while chewing gum. Do you see the problem? This fictional executive has fuzzy language disease.

Our definitions for terms like courtesy and professionalism make sense to us because we know exactly what we mean. But we’re assuming that everyone else knows exactly what we mean. Go have some fun with this: pick a few coworkers and ask them to define courtesy or professionalism or another similar vague term. I’m fairly confident that you’ll find their answers vary from yours in important ways.

Fuzzy language doesn’t happen only in Brown Shorts interviews. Many of the items in our Mission Statements, Codes of Conduct, and Hiring Profiles also are fuzzy. Here are some examples I have collected from not-yet-fixed Hiring Profiles at real companies:

The desired candidates …

• Maintain the highest standards of professionalism

• Treat customers as a priority

• Regard responsibility to the patient as paramount

• Demonstrate positive attitude and behavior

• Lead by example

• Engage in open, honest, and direct conversation

• Respect and trust the talents and intentions of their fellow employees

• Challenge the company’s thinking

All of these exhortations sound nice, but each is open to differing interpretations or even fundamental misinterpretation. When discovering your own Brown Shorts (and ultimately expanding them into Brown Shorts Interview Questions and Answer Guidelines), make sure you know exactly what people are talking about. But there’s a catch to that. Attitudes exist in our minds, and this makes them notoriously difficult to describe. Instead of trying to come up with a verbal portrayal of the attitude, try thinking about the behavioral manifestations of the attitude. For instance, if somebody has a negative attitude, it will probably show up in the way he or she criticizes new changes in the department, interrupts customers when they’re speaking, or always plays devil’s advocate during brainstorming sessions.

Rather than keep this exercise in the realm of vague pseudo-psychological attitudinal descriptions, try to elicit the actual behaviors. The metaphor I give our clients is to think about painting pictures with your words. (We call this a Word Picture and, as I’ve already indicated, later on you’ll learn how to expand this to many other applications, such as performance management.) For now, here’s a quick three-part test to assess whether or not you’re getting enough Behavioral Specificity in your Brown Shorts Discovery interviews:

• Is the person you’re interviewing telling you the specific behaviors?

• Could two strangers have observed those behaviors?

• Could two strangers have graded those behaviors?

It’s important to question whether total strangers could make sense of these interviews because, based on your familiarity with the person you’re interviewing, you too might be making assumptions (you only think you know what the person means). Considering how total strangers could view this situation clarifies any information you might be missing.

If you find that you’re getting too many vague platitudes, you’ll need to do some probing. Two probes that work well in Brown Shorts Discovery interviews are:

• “Could you tell me about a specific instance?”

• “Could you tell me how you knew they were________?”

Here’s an example of how everything fits together. Let’s say you’re interviewing the CEO and she says, “This person just didn’t represent our culture because he would never lead by example.” You may presume to know what she means, but would two strangers? If not, and in this example I would say two strangers would have no idea what “lead by example” really means, you need more information. You might probe deeper by asking, “Could you tell me about a specific instance where that person didn’t lead by example?” Keep asking for more specifics until you get to the place where two strangers could actually observe and grade someone based on what they now know “leading by example” means.

Most of the time that probe will get you lots of detailed information about specific behaviors. But once in a while you’ll get some hemming and hawing where you hear something like “Well, you know, there are so many examples I couldn’t really narrow it down to just one….” Those situations call for a second probe. This is when you’ll use “Could you tell me how you knew that person wasn’t leading by example?” This second probe is a bit more pointed and, in a very polite and subtle way, says “I’m not going to be satisfied with some blanket assertions about their attitudes; I want to know how you came to those conclusions.” The probe is friendly and respectful, but it also forces the interviewee to get his or her head in the game.

So don’t be satisfied when you hear that someone’s attitude doesn’t fit your culture because “he’s just not committed.” Push for more Behavioral Specificity until you hear examples like these:

This person arrives to most meetings late or leaves early. And then, once in the meeting, he avoids extra work, leaving it for his coworkers to do. Just last week, for example, when we were meeting about the Alpha Project, he …

or

When something goes wrong, this person frequently finds another person or department to pin the blame on. Just last week, the Accounting Department became her latest target. In six months I haven’t heard her take personal responsibility for a single mistake; meanwhile her colleagues take ownership every day, like yesterday when …

How many of these executive interviews you should do depends on the size of the organization you’re analyzing. But you should try to get at least two-thirds of the senior or top executives to take part in the interview process. If you’re analyzing only one division, then aim for two-thirds of the executives in that division, and so on.

Next, you can roll this process down even further into the middle and frontline management layers. Again, you want as many leadership perspectives as possible, but here, because of the increased numbers, a 50 percent sample is usually adequate.

RECORDING YOUR INTERVIEWS

As you go through these interviews, your goal should be identifying both your Positive Brown Shorts (attitudes that highlight your high performers) and your Negative Brown Shorts (attitudes that just don’t fit your culture). Ideally, you want to make a short list for each.

If you want to do some advanced textual analysis with expensive statistics software like we do at Leadership IQ, go right ahead. It’s more likely, however, that you’ll be doing this by hand. So as you build your Brown Shorts lists, pay attention to the common themes you hear. Typically, those themes will be significantly similar concerning the people with the wrong attitudes and why their attitudes are so wrong. There will be similar themes in what you hear about the people with great attitudes and why their attitudes are so great as well. A simple tally mark (as if you were voting) will help you keep track of these repeated themes. In the end, the items with the most tally marks will be the dominant Brown Shorts issues, both positive and negative for your culture. You can download a form for recording your interviews at www.leadershipiq.com/hiring.

At this point I’d like to include a special note for small businesses and managers of single departments. You probably feel as though these methodologies were designed for larger organizations and that they may be out of reach for your smaller group. It’s true that many of Leadership IQ’s clients are fairly large, but we’ve certified interviewers from every size organization. We know these techniques work even in three-person start-ups, and you can certainly scale these techniques up or down as necessary. If your department has five people and you’re going to hire one more, you won’t have multiple management layers to interview. And that’s fine—you can still develop your Brown Shorts. Rare is the small business owner who takes the time to sit down and review all of the hiring successes and failures. You can learn much about your culture by looking at the people who are your role models (assuming they’re still with you) and the people who drove you nuts (a good barometer of someone who didn’t fit your culture). The following exercise will help you get started no matter what size your company is.

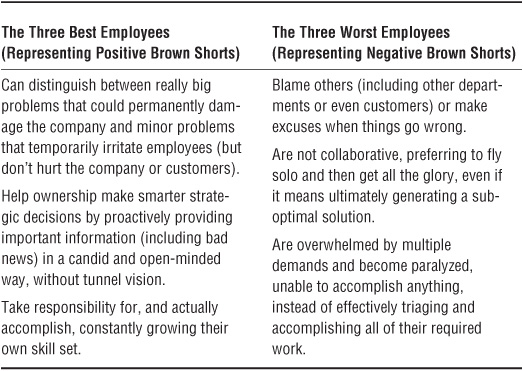

3-3-3 EXERCISE

Timothy is the CEO of a small software company and one of our early certified interviewers. We happened to be chatting on the phone once and I asked him if he had ever done the 3-3-3 exercise. He hadn’t, so I walked him through the process, which involves writing down (in a behaviorally specific way) the attitudinal characteristics of your 3 best and 3 worst employees over the past 3 years. Table 1.1 gives a summary of what Timothy came up with.

I’ve yet to meet an entrepreneur or executive whose eyes weren’t opened pretty wide after doing this exercise. The 3-3-3 exercise is a very pointed way of discovering your Brown Shorts.

GETTING TO THE FRONT LINES

So far we’ve been getting the perspectives of the people doing the hiring. But what about the people who are on the front lines? They’re typically closer to your new hires, so their perspective on who will and won’t succeed is also important.

It becomes more difficult to conduct phone or in-person interviews in organizations of more than 70 people (let alone the Fortune 500 crowd). In these situations, online surveys tend to work best, but you do have to conduct them differently than you did the manager interviews. With employees, you’re not asking about the people who work for them but instead those who work with them. You want to ask them about themselves and their colleagues.

You’re also not starting with a blank slate as you did with the CEO and other executives. You have all the data you collected in the executive interviews, so you should have an emerging picture of your Brown Shorts. You want to obtain validation and more specifics from the folks on the front lines so you can bring your Brown Shorts picture clearly into view.

The survey for your frontline employees will consist of somewhere from 6 to 10 open-ended questions. And the best questions—the ones eliciting the most detailed responses—are the ones built around the rough draft Brown Shorts you’ve already developed.

Imagine that your executive interviews uncover a major attitudinal problem, something that really defines the low performers. Perhaps the problem is an unwillingness to learn new skills on the fly and, more specifically, an unwillingness to take on the personal responsibility for learning those skills. In this case, we might include a question on the employee survey such as “Please describe a situation when you were asked to do something work-related that you didn’t know how to do.”

Questions like this one give you specific answers to help you develop and finalize your Brown Shorts Interview Questions (and the Answer Guidelines you’ll make later). You can also ask questions that will corroborate that you’ve understood the issue correctly. For example, if the interviews uncover that bad attitudes generally involve reacting poorly with customers, but the nature of the poor reactions is still unclear (or the descriptions cannot be categorized), your question could be “Please describe a recent mistake that you’ve seen other employees make in their dealings with customers.”

Questions like this will help clarify the range of issues you deal with and, again, will help flesh out the specifics you need to develop your Brown Shorts. Later in the book we’ll delve further into the specifics of this process, and I’ll show you some specific techniques for making the process work.

When you’re finished with all the interviewing and surveying, you’ll have an amazingly deep understanding of the attitudes that do and don’t work in your particular culture. Almost every time Leadership IQ delivers a Brown Shorts report to our clients, we get feedback that sounds something like “I think you actually understand our culture better than we do (at least before we got the report).” It’s not because we’re so super fantastic smart (although I’d like to think we are), but rather because the process itself is so revealing.

Will Employees Really Participate?

“How do I get my employees to participate in a survey?” This valid question gets asked a lot. The answer is that every time you give an employee survey, participation will increase as long as you do something constructive with the feedback you got from the last survey. “Don’t ask questions you can’t fix” is a critical piece of advice I give anyone considering an employee engagement survey or almost any survey, including a Brown Shorts survey. People are happier to get involved (whether engagement or Brown Shorts surveys) when they know their input is going to result in a positive change.

LifeGift is an organization I’m going to talk about more later in the book. Located in Texas, LifeGift a not-for-profit organ procurement organization that recovers organs and tissue for individuals needing transplants. The organization has worked with Leadership IQ to solve many of its leadership needs, including a number of employee surveys. Sam Holtzman, President and CEO of LifeGift, is one of those rare leaders who successfully negotiates the delicate balance of running a highly successful operation while sustaining a culture that provides emotionally sensitive care and service (a pretty important attribute given the work LifeGift does).

When I asked Sam about the success he’s had getting people to participate in employee surveys, he said, “Employee participation in our surveys was always good, but it’s definitely increased over the last few years. We’ve gotten good feedback, and we’ve applied it to things like orientation and training and gotten great results. Our employees see the value in these surveys and that makes them eager to be part of the process—they’re even willing to give demographic information. We’re up to 92 percent participation at this point.”

MICROCHIP TECHNOLOGY FINDS ITS OWN BROWN SHORTS

Brown Shorts Discovery can be undertaken whether your company is just dipping its toes into attitudinal hiring or is a recognized expert. Microchip Technology is in the recognized expert category, yet it is still pushing the envelope and finding new ways to improve.

Microchip Technology is a leading provider of microcontroller, analog, and Flash-IP solutions. (If you have no idea what that means, you’re probably not a great candidate for the company—and believe me, I’m right there with you.) The short version is that it does microchips (the website is www.microchip.com, after all). It’s a good-size company on the Forbes Global 2000, and it’s growing. In fiscal year 2011 it had nearly $1.5 billion in net sales, which was up almost 57 percent from the year before. And yes, it was profitable growth, with close to 60 percent gross margins. Whew!

But all of those financial results are enabled by Microchip’s culture. The CEO, Steve Sanghi, wrote a book about its meteoric rise to prominence called Driving Excellence: How the Aggregate System Turned Microchip Technology from a Failing Company to a Market Leader. Essentially, Microchip took everything that could influence an employee’s performance and got it fully aligned. The organization clarified and shared its values, got managers to model those values, and refused to tolerate any politics, ego, or arrogance.

I know that description sounds like it came from any number of management books detailing business miracles, so let me give you an example. I mentioned the incredible year-to-year 56 percent sales growth; what I didn’t mention is that the sales force is noncommissioned.

Yes, you read that right—sales engineers without traditional commissions grew sales 56 percent in 2011 at a billion-dollar company. They have bonuses tied to worldwide sales goals, but not the individual incentives you’d typically see. And Microchip has unbelievably low turnover in its sales force (low single digit percentage).

Microchip accomplished all this because it hires for attitude. It finds people who fit its highly collaborative and ego-free—yet still hyper-technical—culture. But the folks at Microchip are high performers who aren’t easily satisfied. It needs more sales-people to continue driving growth, and it wants turnover, as low as it already is, cut in half. So Mitch Little, Vice President of Worldwide Sales and Applications, attended one of Leadership IQ’s webinars on Hiring for Attitude and immediately thereafter we launched a Brown Shorts project.

Mitch Little is a brilliant guy—you can see the results he’s gotten as head of sales. And he’s won awards (like his Stevie Award that the New York Post called “the business world’s own Oscars”) for building an incredible and noncommissioned sales organization. But despite Microchip’s accomplishments, Mitch wanted to fine-tune the company and push further.

Some of Microchip’s Brown Shorts were obvious just from reading the book and reviewing the organization’s awards. But as we began the Brown Shorts Discovery, we learned that there were additional factors driving the company’s success. For example, one of the big Brown Shorts we uncovered was that the most successful sales engineers had tremendously high empathy for both customers and colleagues. And when we probed for more information about the behaviors that define empathy at Microchip (so two strangers could observe and grade it), we learned the following:

A poor fit in the Microchip culture would deal with frustrated (and frustrating) customers by:

• Condescending (“I’m the expert in our products, you’re not, so …”)

• Placating (“Here, have some free software and stop complaining …”)

• Overwhelming (“You want technical specifications? Well, open the warehouse, because I’ve got a truckload of technical specifications …”)

• Challenging (“That last request you made is technically infeasible—tell me how you even arrived at those calculations.”)

• Ignoring (“That customer has a crazy request every time he’s anxious, but ignore it for a day and he’ll settle down and forget about it.”)

In contrast, potential high performers not only avoided all those bad behaviors, but also exhibited:

• Understanding (“A customer got really angry and swore at me up and down. But I knew she was just stressed and reacting in the moment, and I was sympathetic to her plight of being caught between multiple bosses’ requests.”)

• Caring (“Even our best friends sometimes get quarrelsome and difficult, but we don’t abandon them or refuse to help. In fact, when a friend is in trouble, it usually makes us want to get in there and help even more.”)

• Persistence (“I ended up staying on the phone with her until almost midnight, but we finally got things figured out and working right.”)

• Objectivity (“When I felt myself getting defensive, I took a mental step back to get an objective take on how the customer viewed the situation.”)

• Sincerity (“I suggested the wrong product to a customer so he abruptly decided to stop doing business with us. I called a meeting with their management and apologized with no excuses. They’re now back with us.”)

The more we uncovered Microchip’s Brown Shorts—the secret drivers of success that not even the organization had fully recognized—the clearer it became that we could spot future high and low performers a mile away. Of course, after this phase we turned those characteristics into Brown Shorts Interview Questions and Answer Guidelines. But the whole process (for Microchip or anybody else) rests on understanding those key differentiators that drive your success and separate you from everybody else. We uncovered more Brown Shorts characteristics, but I don’t want to divulge all Microchip’s secrets.

Microchip’s culture isn’t for everybody—in fact, it scares away some people (people who wouldn’t fit in anyway). But the organization’s financial results are strong evidence that this is a culture that works incredibly well. And as great as Microchip currently is, they kept digging and further clarifying to reveal the select attitudinal factors that define organizational success. Mitch tells me the whole process is going to cut turnover in half. And given what I’ve seen from Microchip so far, he has me convinced.

For free downloadable resources including the latest research, discussion guides, and forms please visit www.leadershipiq.com/hiring.