5

Scoring the Answers

You’ve got your Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines, and with this you can accurately diagnose who’s likely to succeed, or fail, in your unique organizational culture. But you still need to know how to rate your candidates’ answers against your Answer Guidelines. Let’s start simply, with the form and scale you’ll be using to grade the interview responses. Here’s how it works.

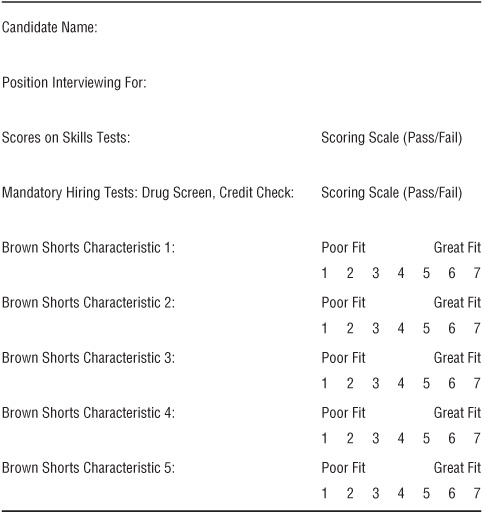

First, it’s a good idea to have an actual rating form. Table 5.1, versions of which you can download and edit at www.leadershipiq.com/hiring, is our suggested starting point.

Table 5.1. Score Your Candidates

You may already have some kind of form or automated talent management system that you use to record the results of a candidate’s skills tests and drug screens. If so, it’s often possible to merge the Brown Shorts rating with these other forms or systems. This doesn’t have to be fancy, and it shouldn’t be complicated or difficult to use. The goal is to have a reliable and consistent way to capture your Brown Shorts analysis so you can make an effective and objective comparison of your candidates.

WHY DO WE USE A SEVEN-POINT SCALE?

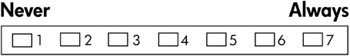

Nonresearchers often look at our rating scale and say, “Huh? Why the seven-point scale? And why are only numbers 1 and 7 labeled?” Without getting overly statistical here (although I’d love to because bad survey scales are a pet peeve of mine), the answer is that seven-point scales provide better data. Figure 5.1, which is a repeat of Figure 4.1 shown here for your convenience, is again an example of our seven-point scale.

There are several reasons why this is the case. First, if you use a narrower scale (like 3 or 5 points), the data usually skew to the side with the higher scores. People typically don’t like checking any box that implies “this person is terrible,” and interviewers are no different. It feels judgmental to make such a serious determination about someone, especially when you’ve only just met the person. And lots of interviewers wrongly believe that nice people don’t give critical ratings. So the tendency is to give higher scores than are actually warranted to somehow show “I’m a good and nice person, and I don’t judge other people harshly.”

The danger in this kind of behavior should be obvious, but the fact remains that this behavior exists. Using a broader scale balances out the impact of this expected (and understandable) behavior. Interviewers can then give a lower score (like 2 or 3 or 4) without feeling too bad about it.

The next rationale for using a seven-point scale is that you don’t want to label every number on the scale. The endpoints in Figure 5.1 are clearly labeled with 1 indicating Never and 7 indicating Always. However, we purposely leave the numbers 2 through 6 empty of any description. We find that it’s too easy for people to have different interpretations of the words on a scale, or to feel that the actual distance between the words isn’t equal. This messes up the scores. Even worse, more description prevents people from giving certain scores; people often won’t give a 1 or 2 because they think the labels are too harsh or too far away from a 3. So our scale has been carefully designed to encourage people to use the full range from 1 to 7 and to not shy away from giving scores on the lower end. This is important because rating inflation presents a very real danger.

Figure 5.1. The Seven-Point Scale

As an aside here, one of the many interesting findings from Leadership IQ’s Global Talent Management Survey is that executives see a significant discrepancy between the number of high performers they actually have and the number of people to whom they’re giving top ratings on annual performance reviews. In other words, there are far fewer high performers than the scores would lead you to believe. As I said previously, rating inflation is a major issue.

You’ll notice that I haven’t mentioned even-numbered scales like four- or ten-point scales. Again, sparing you the math, a rating scale needs to have a middle: a point equidistant between both endpoints. And the last time I checked, 2.5 and 5.5 don’t actually appear on most even-numbered scales. I don’t mean to use this space as a marketing push for my book Hundred Percenters, but if you happen to have a copy of it available, you’ll see a big chunk of the Appendix is devoted to explaining why seven-point scales are the most effective. Check it out if this is a subject you want to know more about. Or visit www.leadershipiq.com and read my articles on survey and scale design.

WHAT CONSTITUTES A LOW SCORE?

I hear this question a lot from the folks participating in the certification process for Hiring for Attitude. Unfortunately, the most accurate answer is “It depends.” It depends on your talent pool, your Brown Shorts, what you’re hiring for, and more. And those are just some of the factors we analyze when we develop standards for our clients. Plus, we take a few candidate pools and statistically analyze the spread of scores to see where the various thresholds occur. But that all takes some work, and I realize that you’re reading this book because you want an actual answer right this minute—so here it is.

First, you need a range that unequivocally indicates when a candidate is immediately out of consideration. Typically, this is represented by a score of 1 to 3. If you get even one response that rates a 1 to 3, the candidate isn’t a fit for one (or more) of your Brown Shorts. And it’s a clear indication that this person shares at least one (and maybe more) big characteristic with your low performers (a good sign this might be a Talented Terror). A score of 1 to 3 is all you need to know. Discussing it further isn’t going to make that person magically turn into a good cultural fit; it’s just going to deplete your mental energy. We’re not talking about the difference between a 6 and a 7 here; we’re talking about the 1, 2, and 3 scores. So if that’s the score, immediately dismiss the candidate from your consideration.

Since this is so important, let’s review. When you’re scoring a candidate’s responses to your Brown Shorts Interview Questions, even one score of a 1, 2, or 3 should eliminate that candidate from consideration. And if you’re really serious about talent management for your whole company, you should remove that candidate from consideration for your other positions as well. If you’re a good interviewer and you know someone does not fit your company’s Brown Shorts, do you really want another manager to hire that person and cause problems for other people? Sure, your area avoided this mistake, but what about those other departments?

TALLYING THE SCORES

Assuming that the candidate clears this hurdle and successfully completes the full interview, all you need to do next is average all the scores together. From there, it’s simple: the candidate with the highest score should be your first choice (assuming that person passes all your other hiring tests).

But highest scores notwithstanding, I’d be concerned if your best scores are in the 4 to 5 range. You really want to see your best candidates rating a final 6-point-something or even a 7. So if you’re finding that most candidates are mediocre fits—not awful, but not great—it’s a sign that there’s probably something broken in your recruiting process (I’ll cover that in Chapter 6).

Another question we hear a lot during certification training is “What if there are several of us doing the interviews and our scores vary?” Well, right now, with your current system, your evaluations probably do vary. That’s why we have the Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines. You already conducted the analysis about what constitutes good and bad answers. That’s your guide. Any discrepancies after the interview should immediately be brought back to that guide for the final resolution. Your Answer Guidelines hold the answers about who will, and won’t, succeed.

WHAT ARE WE ACTUALLY RATING?

This is the single biggest question I am asked, and it’s also the most exciting to answer. (I know that exciting is a relative term, but come on, say it with me: “Ain’t no party like a Brown Shorts party ’cause a Brown Shorts party don’t stop!”) First, you’re evaluating the extent to which the candidate reflects your Brown Shorts. For example, say that yours is a highly social culture where the best employees enjoy working on teams and sharing credit. So you might ask a Brown Shorts Interview Question such as “Could you tell me about a time when working on a team was challenging?” You’ll get a response that you’ll then compare to the sample answers in your Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines. This will let you accurately assess if what the candidate revealed about his or her attitude regarding teams reflected any of the same attitudes about teamwork provided by your current high and low performers.

On the surface, it’s an easily understood process, but there can be a bit more subtlety. For instance, what if the candidate generally seems to share your Brown Shorts, but his answers are kind of vague? Or pretty short? Or rambling? Or anything less than a crisp, clear, factual, and personal answer recounting specific experiences? Well, now we’re not just rating the extent to which the candidate’s answer fits with our Brown Shorts—we’re also looking at the credibility and delivery of his answer. Two different candidates can both say “Yes, I have lots of team experiences,” but one of them could deliver the answer with lots of specifics and the other with empty platitudes. Thus, one of those candidates will get high marks—he can prove his Brown Shorts—and the other, while seemingly in sync with your Brown Shorts, doesn’t have the specifics to back it up.

TEXTUAL ANALYSIS

Here is where the really exciting stuff comes in. Leadership IQ has been engaged in some cutting-edge textual analysis research to assess the differences in language usage between high and low performers. That is, we know things like whether high performers primarily use the past or future tense in their answers, what kinds of pronouns and adverbs low performers choose, and so much more. This is the “rocket science” of our industry, and I have never seen any other group get even close to the level of our research.

So let me share with you some of our “Holy Cow!” findings. We know what constitutes a good answer and what constitutes a bad answer; that’s why we have our Answer Guidelines. So we analyzed the language style and grammar across tens of thousands of Answer Guidelines responses and compared them to see how high and low performer answers varied. The statistics I’m going to share are rounded to the nearest 5 percent. I did this because we’re always adding more data into our analyses and these numbers may change. And given the long life span of books, you may be reading this one years after the initial printing, which means there could be more current data. Certainly use the following numbers to get started, but also go to www.leadershipiq.com/hiring for the latest statistics.

Our textual analysis focused on five categories: pronouns, tense, voice, emotions, and qualifiers. Here are the results.

Pronouns

First person pronouns: The high performer answers (Positive Signal category) contain roughly 60 percent more first person pronouns (I, me, we) than answers given by the low performers (Warning Signs category).

Second person pronouns: Low performer answers contain about 400 percent more second person pronouns (you, your) than high performer answers.

Third person pronouns: Low performer answers use about 90 percent more third person pronouns (he, she, they) than high performer answers.

Neuter pronouns: Low performer answers use 70 percent more neuter pronouns (it, itself) than high performer answers.

So what does all this mean? Simply put, high performers talk about themselves and what they did. In contrast, typical low performer answers contained a lot more second and third person language. High performers might say something like “I called the customers on Tuesday and I asked them to share their concerns.” A low performer might say “Customers need to be contacted so they can express themselves …” or “You should always call customers and ask them to share their concerns.”

High performers talk about themselves and how they’ve used their great attitudes because they have lots of great experiences to draw from. They don’t shy away from using first person pronouns. But low performers don’t have those great attitudinal experiences and are thus more likely to give abstract answers that merely describe how “you” should handle it. This is really nothing more than a hypothetical response; it doesn’t show what that person actually did in this situation. Additionally, research has found that when people lie, they often use more second and third person pronouns because they’re subconsciously disassociating themselves from the lie.

The lesson here is to listen carefully to whether people are talking about “I/me”—which is good—or if they’re talking about “you/he/it”—which is not so good. Figure 5.2 illustrates this serious concept in a more humorous manner.

Figure 5.2. Low Performers vs. High Performers

Verb Tense

Past tense: Answers from high performers use 40 percent more past tense than answers from low performers.

Present tense: Answers from low performers use 120 percent more present tense than answers from high performers.

Future tense: Answers from low performers use 70 percent more future tense than answers from high performers.

In a nutshell, when you ask high performers to tell you about a past experience, they will actually tell you about that past experience. And, quite logically, they will use the past tense. By contrast, low performers will answer your request to describe a past experience with lots of wonderfully spun tales about what they are (present tense) doing, or what they will (future tense) do. Unlike high performers, they can’t tell you about all those past experiences because they don’t have them.

So, for instance, when asked to describe a difficult customer situation, high performers will respond with an example stated in the past tense. “I had a customer who was having issues with her server and was about to miss her deadline.” In contrast, low performers are more likely to express their response in the present or future tense. “When a customer is upset, the number one rule is to never admit you don’t know the answer” or “I would calm an irrational person by making it clear I know more than she does.”

You’ll also notice that those present and future tenses are usually accompanied by second and third person pronouns (“you/he/she/they did”), whereas the past tense is linked to the first person pronoun (“I/me/we did …”).

Voice

Answers in the Warning Signs category use 40 to 50 percent more passive voice than the answers in the Positive Signal category. OK, this one probably requires a little explanation. To keep things simple, let’s talk about active and passive voice.

Active voice: In the active voice, the subject of the sentence is doing the action, for example, “Bob likes the CEO.” Bob is the subject, and he is doing the action—he likes the boss, the object of the sentence. Another example is “I heard it through the grapevine.” In this case, I is the subject, the one who is doing the action. I is hearing it, which is the object of the sentence.

Passive voice: In the passive voice, the target of the action gets promoted to the subject position. Instead of saying “Bob likes the CEO,” the passive voice says “The CEO is liked by Bob.” The subject of the sentence becomes the CEO, but she isn’t doing anything. Rather, she is just the recipient of Bob’s liking. The focus of the sentence has changed from Bob to the CEO. For the other example, we’d say “It was heard by me through the grapevine.”

Notice how much more stilted the passive voice sounds. It is awkward and appears affected, meaning it’s often used by people trying to sound smarter than they actually are. To be sure, there are academic types who rely more on the passive voice, and academe has higher concentrations of this rhetorical style. But more often than not, intelligent people will speak directly, with the active voice. Parenthetically, this lesson should be applied to your writing. Great writers spend most of their time in the active voice. And that’s where your next big memo or report should live.

This issue is not a deal breaker, and in fact, in the sciences, using passive voice might be a Brown Shorts characteristic. But be on the lookout for people who use the passive voice as an affectation to appear smarter than they are. And remember, the answers in the Warning Signs category use this particular style a lot more than the ones in the Positive Signal category.

Emotions

Positive emotions: High performer answers contain about 25 percent more positive emotions (happy, thrilled, excited) than low performer answers.

Negative emotions: Low performer answers contain about 90 percent more negative emotions (angry, afraid, jilted, pessimistic) than high performer answers.

The emotional issue is fairly easy to understand. High performers do talk about being excited more than low performers. However, the real difference with emotion is how infrequently high performers express negative emotions compared to low performers. In all of our research, we’ve seen that high performers don’t get quite as angry as lower performers. It’s not that they don’t get mad and frustrated—they do (and it’s often brought on by low performers). But high performers have more constructive outlets for doing something about these negative emotions. Given all their positive personality attributes, they don’t get quite as viscerally worked up. And because they don’t get as wound up, they’re much more in control of those feelings and less likely to express them in an interview.

Qualifiers

Qualifiers is a broad category that covers anything that modifies, limits, hedges, or restricts the meaning of the answer. This list includes adverbs, negation, waffling, and absolutes.

Adverbs: Answers in the low performer category contain 40 percent more adverbs (think of words ending in -ly, like quickly, totally, thoroughly) than the high performer answers.

High performers are far more likely to give answers without qualifiers. Their answers are direct, factual, in the past tense, and personal. Low performers, on the other hand, are more likely to qualify their answers. For instance, they might use adverbs to amp up their answers because the facts probably don’t speak well enough on their own. So instead of listing a situation where they had a brilliant idea, they might say “I was constantly/always/often/usually (all adverbs) coming up with great ideas.”

Negation: Low performer answers use 130 percent more negation (no, neither) than high performer answers.

Partly due to a more negative predisposition and partly from a need to qualify their statements, low performer answers contain more negations. It’s not uncommon (note the negation there) to hear low performers say things like “I had no idea what to do” or “Nobody in my department really knew what her or she was doing.”

Waffling: Low performers use 40 percent more waffling (could be, maybe, perhaps) than high performers.

Absolutes: Low performers use 100 percent more absolutes (always, never) than high performers.

It may seem strange that waffling and absolutes would go hand in hand, but they do. Both tend to stem from insecurity. “Maybe I was on a team like that …” would be a pretty obvious hedge—the speaker obviously does not want to be pinned down. But the use of absolutes—“the people in this department never know what they’re doing and always ask for my help”—also stems from insecurity and a need to show off. It also shows a tendency toward black-and-white thinking and a lack of intellectual flexibility, which are hardly great qualities.

We can listen to candidates’ language and start to get a good feel about whether they’re headed toward the high or low performer camps. Textual analysis is truly a revolutionary idea, and we’re just scratching the surface of its many applications.

WHEN DO YOU DO THE SCORING?

So, all this analysis and rating is fantastic. But when do we do this awesome analysis? The short answer is that you want to evaluate your candidate as close to the actual time of the interview as possible. This can be tough to do real time, such as while the candidate is still talking, but you should aim for as soon as possible after the interview. Take a cue from clinical psychologists who often have 50-minute hours. They do therapy with the patient for 50 minutes and then spend the next 10 minutes finishing their notes. They capture their thoughts while they’re still fresh and accurate. Otherwise, if you wait too long, you may forget important points. Wait too long, and certain biases creep in, your memory gets fuzzy, and you start confusing candidates.

In fact, two really bad circumstances can happen if you don’t do your interview ratings immediately after the interview. First, your standards change. And more specifically, your standards start to loosen. It’s not because you want them too, but the longer your hiring process takes, and the more candidates you interview, the more tired of the process you’ll become.

I do this stuff professionally, and even I have occasionally thought, “Jeez-Louise, can’t we find anybody that fits? How about we just take the next person with a pulse that walks in the door?” And if you really need to fill this position (for example, because you, as the manager, are doing all the work yourself), then you may become a little desperate. You might start to believe that a warm body is better than no body. Oh, you’ll pay for that idea in a few months, but it just sounds so perfect when you’re frustrated by your flippin’ high standards eliminating all those possible candidates. This is why it’s critical to conduct your evaluations immediately after the interview. You don’t want to start thinking globally about your need to fill this position; instead, all you’re thinking about this one person who was just sitting in your office. That’s it. Don’t sweat the big stuff—just focus on this one individual.

The second big problem with waiting too long to evaluate the interview is that the candidate becomes a memory—you forget who’s who. When you conduct your evaluation immediately after the interview, you never have to go back and reevaluate each candidate. You did your evaluation. It’s done. It is the most accurate it’s going to be, and if you try to go back and redo the scores, those biases I mentioned start to come back full force.

BE SURE TO LISTEN

Finally, you need to listen. I mean really listen—no talking, no interjecting. Zipped lips work well. Here’s a good technique. Whenever you get the urge to interject, bite your tongue and slowly count to three—one one thousand, two one thousand, three one thousand—keeping your mouth shut. The ensuing stretch of silence tends to make people uncomfortable, especially when they’re being interviewed. They start thinking it’s their fault no one is talking and say things to fill the void for fear of looking bad. In fact, when faced with an uncomfortable silence, people will start talking 95 percent of the time. You risk feeling a millisecond of discomfort, but it’s worth it if it elicits the facts you are looking for.

Here’s what an HR Generalist at the University of Washington-Tacoma shared with me regarding her experiences in Hiring for Attitude.

Once we dropped all our leading and hypothetical questions and just asked the Brown Shorts questions, I noticed something really interesting. A surprising number of interviewees didn’t naturally give us too many details about the challenging scenarios that the Brown Shorts questions presented them with.

There was definitely a learning curve on the part of our hiring committee to allow that disconnect to happen. But that’s only because the natural impulse is to jump in there and help the candidate with a follow-up question like “What was the outcome?” or “How did you deal with it?” But the key word here is help, and I had to remind our interviewers that we aren’t there to help the candidates turn themselves into problem solvers (or whatever Brown Shorts we are looking for) when they weren’t. Rather, we’re there to find out if they already were problem solvers or not.

It took making a slight adjustment in our thinking, but now we all agree that we get far more honest answers when we don’t ask the candidate to “tell me what I want to hear.” So now when we ask a Brown Shorts Interview Question, and the candidate can’t offer up a real-life situation where this happened to him or her, it tells us that this individual likely doesn’t possess the Brown Shorts characteristics that we critically need.

As for the candidates who do give us detailed information, having our Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines has made us so much more prepared when making our hiring decisions. The Answer Guidelines allow us to be objective and get all our interviewers on the same page when rating candidates. Typically the people we interview are really different, and the interview committee members already have a gut feeling after interacting with them. But having those Answer Guidelines down on paper makes our hiring decision that much more defensible. We know we did not hire on a hunch; we knew what was critical for the position, and that is what we hired for.

MORE ANSWER GUIDELINES EXAMPLES

I’ll close this chapter by leaving you with some more snippets from a real-life Brown Shorts Answer Guidelines. It should be easy to identify this organization’s Brown Shorts from their list of Warning Signs and Positive Signals. And make sure to pay attention to the pronouns, tense, voice, emotions, and qualifiers used. What do they all tell you about the candidate?

Brown Shorts Interview Question: Could you tell me about a time when you had to think outside the box?

Warning Signs: These types of answers can indicate a poor fit with the organization’s culture.

• “I’ve never had a challenge I couldn’t beat. At my last job I was the ‘go-to’ person when we needed innovative new ideas. Of course, my boss wasn’t always my greatest supporter; he felt some of my ideas challenged company policy. But the customers sure liked that I was able to find ways to, you know, sorta dodge the rules and give them what they wanted. Shoot, I even had some customers who would call me at home in the evenings or on weekends to talk about what we might be able to do. And I never minded taking those calls. For me, my job always comes first. I sure moved a lot of product at that company. I bet they miss me.”

• “I only had to make the mistake once of stepping into a skill set that was unknown territory to figure out that being too innovative isn’t a great thing. Besides, what I’ve found is that the demands for that kind of outside the box thinking usually only happen when somebody else messes up and puts us in an emergency situation. All I ever heard my last boss say was how important personal accountability was. He was like a broken record about it. So shouldn’t that mean that the person who made the mess is the person who cleans up the mess?”

• “Any kind of opportunity to stretch my brain and really prove my value to the organization interests me. At my last job I was recognized for several of my original ideas. Perhaps you noticed that I listed some of them on my résumé? There should be one more award listed there, but I lost it due to bad office politics. But yeah, I’m great at out of the box thinking.”

• “Right, my team wasn’t really involved with that level of thinking, but I might have an example that applies. It was just really difficult at my last job for anyone to get an idea under management’s radar. And that kind of killed any incentive for innovative thinking, you know what I mean? But I’m sure if I were given the challenge in a different kind of environment, I would come up with something really clever.”

• “So, the customer seemed pretty happy with my solution. Of course, management was another issue, but that’s just the way they were. But it’s a lot more of a hands-off and open environment here though, isn’t it? I mean, I would have a lot of space to kind of do my own thing, right?”

• “So when I couldn’t get anyone to go with my idea, I admit, I dramatized the situation a bit to make the need for my idea appear a little more attractive in everyone’s eyes. But it worked. People started listening to what I had to say, and we went with my idea. In the end there were really only a few people who were really unhappy about that. But they were the kind of people who are never happy about anything. But you definitely don’t want me to get started on that … or do you want to hear about it?

Positive Signals: These types of answers can indicate a good fit with the organization’s culture.

• “First, I checked in with the customer to make sure my idea would meet expectations. And that was a good call because I found that I did have to make a few changes. Then I had to consider just whom I could pull from each department to put together a great team to execute my idea. I didn’t want to leave any one department vulnerable, because I knew this was going to take at least a week of concentrated effort from the entire team. But at the same time, I wanted to make sure I got the best people so as to meet, and ideally even surpass, the commitment I had made to the customer.”

• “I didn’t hesitate to ask around and gather as much feedback from my peers as I could get. Not that I put the burden on anyone else to come up with my answer for me, but I am extremely aware of the value of being open to other people’s ideas.”

• “With my idea, I was able to satisfy the customer’s needs and end the conflict. But I also resolved an ongoing communication issue, which I discovered was originating from my organization. I actually found out that we had a history of these kinds of communication problems that typically led to some other kind of problem. I had to play investigator and really get in there and break the process down to see where the disconnect was taking place. And then, of course, before I approached my boss with the problem, I came up with a few solutions to rectify the problem. That was six years ago, and as far as I know, it was the last time anything like that happened. And I know if you ask my supervisor at that job, he’ll tell you it’s because of the changes I suggested. Not that I necessarily need the credit for that, but I do feel really proud of being an integral part of that change.”

• “It required a lot of courage for me to stand behind my idea. But I was able to do it because I was confident that I had covered all my bases and that this was the very best solution for both the organization and the client. Win-wins are always good in my book.”

• “It was really pretty thrilling because I had never faced a quality control challenge of that magnitude before. But then it got even better when my idea resulted in increased revenue to the company and solidified the relationship with that customer. It was one of those days when I left work and my head was just floating in the clouds. I love those kinds of days.”

• “I just could not get the customer to bite via any of the usual channels. But there was no way I was going to give up, because I knew we could make him happy. So I got permission to take one of their products home for the weekend, and I created a prototype of what it would look like if they were using the program I had suggested. Well, the customer loved it as soon as he saw it. He didn’t even need to hear how much time and money it would save his company. Though, of course, I had prepared a full report that I shared with him. It was a really cool experience, and I really liked working with that customer. But then, all our customers were great to work with.”

For free downloadable resources including the latest research, discussion guides, and forms please visit www.leadershipiq.com/hiring.