3 Basic change management (phase 1)

“The journey of a thousand miles begins with one step [in the right direction] Lao Tzu”

In this first phase, we’ll be taking our first step. In order to ensure our first step is, as Tzu implies, ‘in the right direction’, we must first take an inventory of how change management is currently being handled.

Formally done, this is what’s commonly called a ‘gap analysis’ – an inventory of current state of change management along with a reasoned declaration of desired end state. Whether undertaken formally, or informally, it’s important to have a good understanding of the current and desired future state of change management, as I’ll explore in this chapter.

In the last chapter I talked about finding the right balance between attempting a too-large change management implementation on the one hand and a too-small one on the other. In this chapter, we’ll examine the first of two phases scoped to ensure success.

If your organization is like many others, a basic change programme to review changes before release into production may already be in place. In that case, you should treat this chapter as a review to ensure you’ve got the basics covered before you move on to the next phase. Pay special attention to the success criteria to assess when you’re ready to proceed further. It may be that the current process is lacking some of the essential elements I describe here. As I believe they are critical for successful maturity, I would recommend an initial phase that ensures all the elements described in this chapter are in place before moving on to Chapter 4.

Far too many change management programmes begin with a primary focus on process, instead of on people and related issues. Unfortunately, experience shows time and again that the process, by comparison, is relatively easy. As mentioned in the previous chapters, the real challenges are the cultural issues you’ll face and being able to produce tangible results in a timely fashion.

It’s worth noting that the concept of continual improvement is implicit in this publication. Any capability that doesn’t include continual improvement as a core element is one that is destined to fail to meet future needs. Change management must be designed to be adaptive.

The focus for this first phase is to establish a successful basic change management programme, one that lays a solid foundation that can easily be matured to fit the changing needs of the organization (more on this aspect in the next chapter). This approach avoids unnecessary complexity, minimizes cultural resistance, and focuses on the business outcomes that change management can deliver.

3.1 Phase 1 goals

Because the concepts and ideas embodied by ‘change management’ mean different things to different people, it is vital to be very clear about what we are trying to accomplish in this first stage. If you don’t carefully establish and manage expectations, whatever you do will be viewed by some people as a failed attempt, which places your new change programme at unnecessary risk, right from the beginning.

The goals for the first phase are selected to maximize the chances of success and minimize the difficulties in adoption.

The first phase goals:

• Build a culturally relevant case for change management

• The importance of change management

• What’s in it for the stakeholders

• Introduce the concept of change control

• Show early results, demonstrating value to the business

• Reduction in change-related incidents

• Increase in successful change implementations

• Ensure cultural adoption

• Manage the IT environment while minimizing:

• Bureaucracy

• Unnecessary delays

• Organizational resistance

• Set the stage for future maturity.

3.1.1 A case for change management

I’ve said a lot about people and culture being the biggest challenge you’ll face when starting a change management programme. Not surprisingly, then, we start with getting people on board.

We start this process by creating and communicating a clear case for change management, by explaining why, exactly, the organization needs to invest in change management. The case should address key concerns such as:

• What’s wrong with what we have been doing?

• Why do we need to do this now?

• How will the change programme make things easier or better for me and my team?

• What will the organization gain from formalizing change management?

The case must be consistent with management’s expectations for the change management effort. Establishing clear senior management support for (and expectation of) change management will go a long way towards setting the proper tone for the upcoming programme. Anything less, as I’ve said, is to risk failure.

It is important to take the time to personally deliver the change management message. One on one with key stakeholders is ideal, In addition, it is critical that your message for change management is clear and consistent, and it must also be genuine. If IT staff perceive that you’re just doing someone’s bidding, or don’t have a real passion for it yourself, the message will be clear – the effort really isn’t that important, and their support is optional.

These conversations should be two way. Take the time to communicate the change management message, but also take the time to listen to other people’s thoughts and opinions on the matter. Include their input in the planning process as much as practical.

The importance of getting the support of IT staff cannot be overestimated, especially in the first phase.

3.1.2 Introducing change control

The idea that change should be controlled is not new. Changes are a major source of incidents and (negative) business impact that is almost entirely under the control of the people charged with design through to deployment. The ability to anticipate and avoid negative business impact has always been part of good operational practice.

For many years, internal and external IT audits have been concerned with ensuring that changes are properly requested, documented, approved and implemented to ensure no possibility of unauthorized changes. In addition, and irrespective of the type of organization (e.g. banking, government, retail, aeronautics), there will almost certainly be regulatory requirements that are already being taken into consideration.

One of the concepts of change control is the idea that all changes must flow logically from business requirements in support of business objectives. This means that change management is responsible for ensuring the alignment of changes with those objectives. This issue falls under the umbrella of IT governance, which is outside the scope of this publication, but I include key elements as they relate to change management.

If there is only a technical view of change management, the governance aspects of change management remain unaddressed. So, while changes may be effectively implemented with no apparent negative impact, the organization has no way of demonstrating that each change is appropriately authorized and supports defined (and documented) business objectives.

I’ll cover change policy later, but it’s important for management to clearly communicate their expectations for change management – especially the governance aspects that may not be self-evident to technical staff. With a clear change policy, then, IT management can effectively execute change at the operational level in support of policy expectations.

Every IT organization has some form of change management. There’s no such thing as an IT team that doesn’t implement changes that are managed in some way – ad hoc or formal – with varying degrees of success.

One of the key objectives in the first phase is to successfully introduce the concept of change control.

Change control includes these key aspects:

• Operational effectiveness

• Risk management

– Negative impact reduction

– Business risk

• Cost optimization

– Rework reduction

– Business impact reduction

• Communication and coordination

• Governance

• Achievement of business outcomes

• Time to value

• Compliance (regulatory and otherwise).

If your organization has little or no formal change management in place, some of these aspects are probably not addressed effectively. For instance, technical staff may be used to managing their own changes, and while they may recognize the need to be effective in managing the operational aspects of change (technical details, prevention of interruption to services etc.), they may not perceive the relevance of the change governance and regulatory compliance that comes with formal change management. This is one of the major challenges you’ll face.

From a technical viewpoint of change management (almost as an extension of software testing and quality assurance), it’s easy to see how the shift to a more formal approach and introduction of additional oversight could be perceived as criticism of staff – that they are doing a bad job and so now changes need to be reviewed by others from outside IT. This unintended insult is usually the initial source of cultural resistance. The solution is to engage stakeholders in order to encourage them to suggest a wider range of reviewers; engagement is an important aspect of establishing and managing expectations. You need these very staff to be on board with your change management efforts; alienating them at the very beginning is counterproductive.

It is important to develop a clear understanding of the organization’s current view of change control. This allows you to establish a plan based on the gap analysis between the current and desired states. This approach supports the creation of an implementation strategy that leverages the current capabilities and success of the teams while carefully introducing new concepts.

Take the time to ask, and understand the answers to, the following questions:

• Who authorizes changes to IT services?

• Are changes reviewed, and if so, by whom?

• Peers

• Technical leads

• Unit managers

• Who is accountable for the success of individual changes?

• How are changes coordinated (or not) among the various technology teams (infrastructure, application development etc.)?

• How are changes communicated and coordinated with customers?

• Is there a project management capability? To what degree does it manage the project-related aspects of change management?

• Portfolio management and optimization

• Business prioritization

• Clearly understanding desired business outcomes

• Does the organization’s incident management process track change-related incidents?

In addition, it is important to understand some of the cultural elements that interplay with the introduction of change control:

• Teamwork and communication culture

• Siloed versus collaborative

• Us versus them

• Open communication across organizational boundaries

• Risk culture

• Organizational appetite for risk

• Calculated risks encouraged to achieve organizational goals

• Balance versus elimination

• Fixing blame versus fixing issues

• Empowerment versus avoidance of blame

• Leadership culture

• Role and competency of leadership and management

• Command and control versus empowerment

• Policy compliance versus strategy and goals.

All of these factors come into play as you implement change management. It’s impossible for me to give specific advice regarding how to address all the cultural issues you’ll encounter as there isn’t a single approach that will work in every situation. However, one thing I can assure you: you will face these and other issues. It would be unwise to proceed without taking stock of this fact.

The opposite of controlling changes is letting changes control us (or more correctly, controlling the production environment). This puts not just IT but the entire organization at great risk.

3.1.3 Showing early results (business value)

Many change management efforts begin with strong organizational support, starting with the senior management who are convinced that more effective change management will increase customer satisfaction with IT services. This is a great place to start, but unfortunately this initial support will fade if the programme doesn’t show improved results, quickly.

The typical process-focused change implementation frequently includes a lengthy analysis and requirements gathering phase that often exceeds the management’s timeframe for demonstrating concrete results.

Senior IT management face tremendous pressure to deliver business results. If your new change management effort doesn’t show tangible improvement in change-related incidents in the short term, you risk the loss of support; management is likely to be forced to move resources to other more pressing business-value-generating activities.

The challenge is to produce tangible results quickly, at the same time laying a solid foundation to use as a basis for further improvement. Use the concepts of continual service improvement and ‘Agile’ development methodologies as part of your critical strategy for sustained change management support and success.

In sum: start small, show results. This builds support and momentum that is critical to maintain both IT staff and management’s support.

3.1.4 Cultural adoption

As I mentioned previously, crafting a process to manage IT changes is relatively easy. There are many sources for ‘standard’ change management processes – including the various best-practice volumes; I strongly endorse these as excellent sources of process information.

But these frameworks don’t address the people side nor the organizational issues of adapting the material to fit the organization. Adopting the processes as recorded in the framework ignores the recommendation to adapt (also included in the framework) in order to fit the business needs. Adopting is easy; adapting is the hard part – and is the source of most failures to implement a change management process that works and can be matured to fit the changing needs of the enterprise. Cultural issues are nearly always responsible for disappointing results.

Ignoring the organizational culture, and how the new change management programme will fit into it, puts your efforts of great risk.

3.1.5 Manage the IT environment

Given the complexity of the modern IT environment, if there is no effective change management capability, business outcomes and value are at risk. Minor changes in one seemingly isolated system can have far-reaching negative impacts in other areas and in ways that are hard to predict.

One of the most common reasons to add or improve a change management programme is to get a better handle on what’s happening in the production environment, with the specific goal of reducing both the frequency and impact of change-related incidents.

This first phase provides guidance to allow you to identify and put the right controls in place to proactively manage stability and uptime and minimize adverse impacts on the business.

3.1.6 Future success

Most organizations will eventually need a mature change management capability. If the early efforts are rocky or disruptive, it will make it difficult (if not impossible) to get the required support for future improvements. The same is true if the organization views change management as only a technical last check to avoid failures.

The method in this publication puts a premium on not just the establishment of a basic change programme but the successful laying down of a solid foundation to support additional maturity based on experience and changing business needs.

If you start small, show early results and address cultural issues, you are more likely to maximize both the immediate and long-term chances for change management success.

3.2 Basic change management process

One thing that is common among all IT organizations, from the one-person shop to the major multinational corporation: they have some form of process for application/service development and another for release and deployment into the production IT environments, where they’re used by people to do the work of the company. How these changes are implemented is at the heart of basic IT change management.

Without formalized change management, it is not uncommon for different development teams to have different practices around how changes are moved into production. Some organizations have a well-designed development and test environment to promote changes to production while others may develop changes in production itself. Some teams may have highly structured processes for handling production changes while other teams are completely ad hoc. Infrastructure teams – especially those responsible for data centres and other highly critical areas – often have sophisticated controls in place to minimize business impact.

Your organization may have haphazard and highly inconsistent change processes, and that’s the point – you must first understand how changes are currently being implemented in your environment before introducing something new. It isn’t safe to assume that all changes are implemented in the same way, with the same degree of diligence and rigour (or the lack thereof.) Take the time to understand how your organization handles changes.

Regardless of how new or changed services are developed and released, the most basic change management step is to insert a review after the development work is complete and before the change is released into the production environment.

This review step is the beginning of formal change control and starts with the formation of a change advisory board (CAB) invested with the review authority. It is, in essence, the addition of a quality inspection point.

This is a critical first step in introducing formal change management. All changes should be properly planned, built and tested before being reviewed by the CAB.

For many organizations, the CAB is the first time a cross-functional group will come together to review changes.

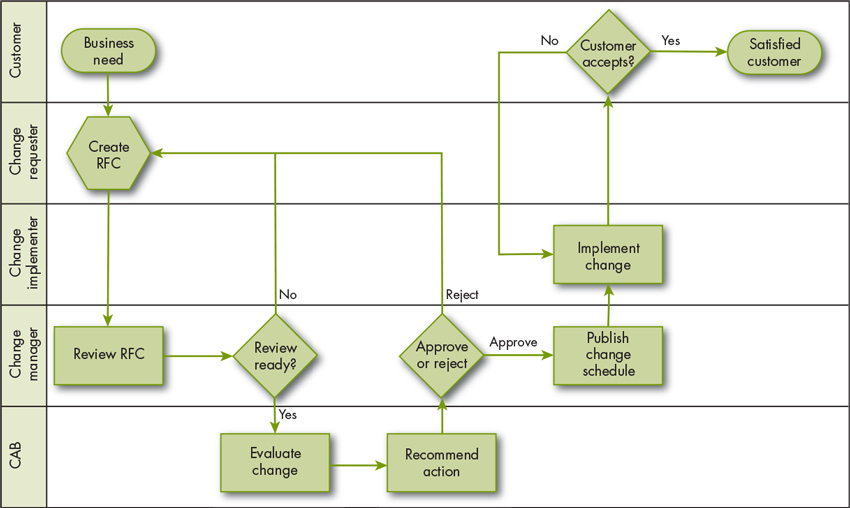

Figure 3.1 shows more details of the basic process flow, and how the various roles work together.

Figure 3.1 Phase 1 change management process flow

Changes start with a business need

A change always starts with a business need. This is fundamental for a change programme that is focused on business value. In practice, of course, many changes arise from within the IT organization. This is normal and expected, but the point here is that every change must be viewed from the standpoint of the customer. This is not a minor semantic – all changes are done for reasons that support business outcomes. To effectively manage changes, we must understand what the intended outcomes are, keeping in mind that valid outcomes can include ‘continued stability’, ‘upgrade to maintain supportability’, ‘addressing capacity issues’ and the like.

The view of change management as primarily an internal IT activity that only deals with the technical details of changes has sabotaged many well-intended change efforts. A change programme with this viewpoint struggles to mature beyond a very basic level.

To get started on the right path, change the approach to view changes from the standpoint of their value to the business as early as possible in your change programme.

The following is a description of how the process proceeds.

Once a need for change has been determined, the change process should be initiated by submission of a completed request for change (RFC) to the change manager, who should review it to determine whether it’s ready for a CAB review.

Once the RFC is judged to be ready, the CAB evaluates the request and recommends action to the change manager. The change manager typically follows the CAB’s recommendation, though there may be cases where changes require approval by a higher authority for that type of change or level of risk.

Approved changes are put on the change schedule as approved and the requesters and implementers are notified of the authorization to proceed.

After implementation begins and before the work on the change is considered complete, every change must be fully tested, and accepted by the customer.

Post-implementation testing is designed to ensure that the change achieves the desired results and without unintended consequences. Make the definition of test plans part of the change request. Any parts of the system that might be impacted should be tested as well. Full system regression testing is ideal, though not always practical or possible. If your organization lacks a formal test capability, some form of elementary testing must be performed to ensure change success.

Note that not all changes require formal customer approval – but at a minimum, all changes must be evaluated to ensure customers are not adversely impacted. For instance, if the service performs poorly after the change, the change should not be considered successful.

The concept of formal customer sign-off will be new to many organizations. For larger changes, project management handles customer acceptance. At this stage, it is enough to recognize that a change is deemed to be successful when the stated business outcomes are achieved – not when the technical implementation is complete.

The key steps are explored in more detail below.

3.2.1 Change policy

Because of the varied understanding of the practices that are part of change management, it is important to develop a clear and consistent picture of company expectations before making changes to existing practices. This is done with the creation of a change policy (a clear and concise statement of expectations, approved by management) that underpins the governance of the new change management approach.

Developing a change policy is important to create clarity of purpose and set expectations. The policy should clearly state management intentions around how change management will work. The policy documents what management expects to achieve from the change management effort.

The tone and formality of the policy should be consistent with the company practices. It needn’t be lengthy or complex; in fact, every effort should be made to keep it from being heavy-handed and consequences-oriented, especially in the first phase.

It should address these key elements:

• Objectives of IT change management

• Scope of changes to be managed (what changes are subject to change management)

• High-level process flow

• Agreed definitions of the types of change:

• Normal

• Standard

• Emergency

• Establishment of roles and responsibilities, and drawing up of a RACI chart (change manager, CAB etc.)

• Expectations for compliance (what happens if change management is bypassed?)

• Establishment of change windows and how exceptions are handled

• Critical success factors (CSFs; two or three at most) and key performance indicators (KPIs) to support each CSF

• Determination of key metrics to measure and report on the performance of the change management process.

Appendix A shows a sample change policy. It should not be used as is, because each organization is unique, and the policy must reflect the needs and expectations of your organization.

Communication is key to a successful change programme, and a clear policy statement is key to communicating management expectations.

3.2.2 Requests for change

The change management process begins with the creation and submission of an RFC. This is how change requesters formally notify change management of the need for a change. It’s called a request for change because it requires review before being approved (or rejected) by the change manager. This may seem like a trivial detail but it can be the source of resistance if the staff were previously empowered to make changes without any oversight and now must make a formal request that could be denied.

Appendix B gives an example of typical fields required for an RFC. The fields vary from organization to organization depending on local needs. To avoid the CAB becoming (or remaining) internally focused on technical details, it is important that every RFC explicitly contains a section (or statement) that addresses the reason for the change which should describe the expected business outcomes.

Only include information in the RFC that is necessary for the decision-making process (including the risks if the change is approved and if it isn’t). Don’t include information that isn’t relevant to the making of the decision. Additional fields should be added only as specific needs are identified and their use is deemed helpful in the process of reviewing changes more smoothly.

The RFC is submitted to the change manager. I prefer to use simple methods – a spreadsheet for example – because they can be readily adapted as change management matures. This helps keep the focus off the tool and on the business of effectively managing changes. In the case of the spreadsheet, the requester makes an entry on the spreadsheet and notifies the change manager of the submission. When the change manager believes that the RFC is ready for review, they will notify the requester and put it on the agenda for the next CAB meeting.

RFCs can be raised for a variety of reasons, including:

• Projects for new or changed services

• Issues arising from daily operations (incidents)

• Normal changes – maintenance and upgrades

• Service improvement plans (often associated with continual service improvements efforts).

As the RFC progresses, the change manager is responsible for ensuring the status is updated and communicated to the appropriate stakeholders. Examples of possible status updates to be included in the workflow document are: submitted, pending, under review, approved, and implemented. The pending RFC list, filtered by the review date, becomes the agenda for that CAB date.

3.2.3 Change types

Changes should be categorized by type, which helps to ensure proper handling.

There are three main types of change request, as shown in Table 3.1. As mentioned above, the change policy should include these definitions along with high-level process expectations.

Table 3.1 Types of change request

| Change type | Description |

| Normal | Normal changes require a normal CAB review and are approved by the change manager upon advice from the CAB. Most changes that come to the CAB are of this type. |

| Standard | Standard changes are changes that are low risk, are performed frequently in daily operations, and follow a documented process that's been previously reviewed by the CAB and pre-approved by the change manager (see Chapter 5 for more details). |

| Emergency | The emergency change type is reserved for those situations where there is a significant risk that must be immediately addressed to avoid dire consequences (see section 3.2.6.6). |

3.2.4 Change priority

RFCs should be prioritized based on business needs, not technical capability. The purpose is to ensure the changes with the highest priority to the organization are considered before changes with a lower priority. Priority should be based on both business urgency and business impact and aligned with the organizational governance.

Table 3.2 gives an example prioritization schema. There is no single correct schema for prioritization; however, part of the change evaluation process should validate and establish priorities for each change. Regardless of the particular schema chosen, the objective is to align change efforts with the priorities of the organization.

Table 3.2 Change priorities

| Change priority | Description |

| Urgent | Reserved for changes of the most critical nature to the company |

| High | Changes that are causing severe impact to a significant percentage of users, or having an impact on critical business functionality |

| Medium | Impact is not critical, but the change cannot wait until the next scheduled release |

| Low | Change is required, but is low enough that it can be included in the next scheduled release |

RFC submitters should assign an initial priority based on their analysis of the business urgency and the business impact of the change. The CAB must validate the initial priority and weigh it both against the other RFCs in the works and against the organization’s priorities and governance processes.

3.2.5 Roles

Formal change management requires clearly understood roles and responsibilities. This is usually done in the form of a RACI chart.

Table 3.3 describes the key roles and a summary description of the associated responsibilities.

Table 3.3 Change management roles

| Role | Description |

| Change management process owner | Ultimately accountable for the change management process itself (i.e. the design, implementation, governance and ongoing improvement). The role includes the development and maintenance of process documentation and ensuring the documented process is followed in practice. In IT service management (ITSM), all processes have a process owner. |

| Change manager | Responsible for carrying out the day-to-day tasks required to administer the process according to the documented policy. In smaller organizations, this role is often combined with that of the process owner and carried out by a single person. In larger organizations, there may be several change managers, each with responsibility for a geographic region, technical domain or other logical division of responsibility that makes organizational sense. Regardless of the structure, it should be clear that a change manager has both ownership and accountability for the changes coming through the change process. |

| CAB | Works as a high-level group to review proposed changes, including analysing risks and potential negative impacts, in order to provide the change manager(s) with expert advice on whether particular RFCs should be approved or rejected. |

| CAB member (see section 3.2.6.2) |

Uses their knowledge and experience to evaluate RFCs. Consults with their team to ensure they are fully briefed on the implications of a change before CAB meetings. |

| Change requester | Documents the reason for and expected outcomes of a proposed change. Completes and submits the RFC form. Answers questions from the change manager and CAB – and may attend the CAB meeting to represent the change. |

| Change implementer | Responsible for the actual implementation of the proposed change. If the change is large or complex, the change implementer is often a senior technical staff member, operations manager or project resource. |

3.2.6 Change advisory board

The CAB is the heart of basic change management and its creation is the beginning of formally managing changes.

This group is frequently misunderstood to be the change approval or authorization board. It’s a distinction that’s important to get right from the beginning: the CAB is advisory. This is because its job is to review proposed changes and advise the change manager of the results of its findings. It’s the change manager who ultimately approves (or rejects) the changes.

Is the CAB a voting body?

Some organizations strongly embrace the concept of committees, which often includes having formal chairmanship and voting members. For such organizations, it’s natural for the CAB to employ this kind of structure.

What results is a change process that is highly focused on the CAB and its regular (typically weekly) meeting that is chaired by the change manager.

I strongly advise against implementing the CAB in this fashion. This type of committee approach tends to establish rigid and inflexible authority centred on the CAB itself.

As your change management programme matures, the CAB should be increasingly concerned with the end-to-end quality of the change capability and less about individual changes. The role of the CAB is to ensure that the quality of all changes meets the needs of the organization. This places the focus on the outcomes of change management, not the process, and most definitely not on the CAB itself.

Because it is so key to a successful early adoption, let’s take a close look at the CAB.

3.2.6.1 CAB role

‘CAB’ and ‘change management’ are not the same. Change management is the broader capability that manages the entire process of raising, reviewing, evaluating, approving, tracking and overseeing all changes. The CAB is focused primarily on reviewing change requests. The review should address risk associated with implementing and not implementing the change, including potential unintended consequences (e.g. the impact and relationship of this change on other changes).

The CAB fulfils its role by:

• Reviewing RFCs (seeking additional advice of subject matter experts, as needed)

• Asking probing questions to fully understand the proposed change and the business purpose

• Questioning the expected return on the investment required for the change

• Evaluating the proposed change for risks and determining whether the implementation plans appropriately address those risks

• Evaluating whether the proposed change is likely to produce the intended outcomes without adverse impact on the business

• Ensuring the change is evaluated in the context of any related changes

• Scheduling and prioritizing changes

• Ensuring the proposed timing is appropriate (doesn’t conflict with business activities, other changes or operational activities)

• Determining the likelihood of unintended impacts

• Making recommendations to reduce risk, increase likely success and minimize adverse impact on the business

• Requesting a more in-depth, formal change evaluation for a given change if deemed necessary. The CAB uses the findings of the change evaluation to assess the change

• Ensuring there is clarity with respect to who will have the responsibility to implement, test and deploy the change

• Advising the change manager of its findings and recommendations.

The CAB can perform its role informally through email, or formally through a chaired meeting, where minutes are taken and people raise their hands to speak to the board. The most common form is an open dialogue, facilitated by the change manager. The CAB members discuss the various aspects of the proposed change. The change requester is present to answer any questions the CAB may have.

The culture and the business needs of the organization determine what’s best in each situation, but I strongly recommend against a format that intimidates requesters and emphasizes the authority of the CAB. This format will become a significant source of cultural resistance and a liability to further maturity of change management.

3.2.6.2 CAB membership

The CAB is made up of two types of members:

• Regular (permanent) members

• Ad hoc members.

Permanent members are typically senior representatives from the various disciplines, each with broad and deep knowledge of IT generally, and their representative discipline specifically. These members are generally at all CAB meetings and provide ongoing expertise and continuity, which is important as the CAB’s culture develops. In the first phase, it’s not uncommon to have a broader permanent CAB membership. As it matures, there will be more reliance on a few core members and more expertise brought in only as needed, depending on the change under consideration.

Ad hoc members are chosen for their specific knowledge in a particular area and are called upon based on the nature of the request(s) under review. It is the responsibility of the change manager to ensure that the right expertise is available so that each RFC is adequately reviewed.

In this first phase, it’s especially important to select the right people for the CAB. The credibility of the newly formed CAB will be largely contingent upon the combined credibility of its initial members. Careful attention should be given to select members who:

• Have strong expertise in one or more technical disciplines

• Have excellent communication skills

• Are widely respected in the organization

• Work well across organizational boundaries.

The CAB is comprised of technical staff and key decision makers. There are no set rules about who is on the CAB. The key is that each member possesses respected expertise and knowledge.

The CAB should include representatives from all IT functional areas and technical disciplines, key decision makers and business stakeholders, as appropriate.

Typical CAB membership:

• Senior network engineer

• Senior application developer

• IT operations managers

• Service desk representative

• Infrastructure engineers

• Senior security engineer

• Information security officer

• Standard change workgroup leads

• Business relationship manager(s)

• Service owners

• RFC author.

The change manager must analyse the RFCs scheduled for review at the next meeting and ensure the necessary specialized knowledge is represented at the CAB meeting. For instance, input from a senior network engineer would be of benefit when reviewing an RFC for changing network routing architectures.

3.2.6.3 CAB scope

One question often asked is, ‘What changes should be submitted to the CAB?’ The simple answer is that all changes to the production environment, or those that have the potential to disrupt production services, should be under change control. But that answer carefully dodges the real question, which is, ‘Must all changes submitted to the CAB be under change control?’ – and the simple answer is yes. In this first phase, we are introducing the concept of change control, and it would severely undermine that objective if we were to do otherwise. (I introduce standard changes and other means of optimizing change management in Chapter 5.)

Release management is covered in Chapter 4. You’ll find a discussion regarding grouping changes into logical collections called release packages that are reviewed as a whole. I’ll say more about these and other strategies for optimizing the CAB in Chapter 5. For now, suffice it to say that all changes are under the authority of change management. As the process matures, it works through multiple mechanisms – not just the CAB. Over time the CAB should become less focused on individual changes and more on the overall change capability, with the goal of improving change outcomes without direct review (again, see Chapter 5 on optimizing change management).

3.2.6.4 CAB authority

The change policy should be clear about change authorities. As stated before, the CAB is part of the overall change process but is not a decision-making body. The change manager is ultimately accountable for ensuring changes are approved/rejected by the appropriate change authority, and must take into account the complex and often conflicting interests of stakeholders – including the business itself.

The change manager will generally follow the advice of the CAB, but can approve changes (for many reasons) that the CAB has recommended against (and vice versa).

3.2.6.5 How the CAB works

The change manager compiles a list of RFCs that are ready for the next CAB review process.

Policy around submissions to the CAB should include a cut-off deadline, so the change manager and the CAB have time to review changes before the CAB review. Requests that come in after the deadline are generally pushed to the following meeting unless the RFC has some high business urgency or impact and the change manager decides to accept it into the current listing. Once the CAB list of RFCs is complete, the change manager notifies CAB members – often via an email that includes either a list of the RFCs or a link to a location where they can be found.

In the first phase, face-to-face meetings are preferred. If you have people at multiple locations, remote members can be included in the proceedings by using either voice or video conferencing.

The CAB meeting

CAB members are expected to review the RFCs prior to the meeting. They are encouraged to research the change, glean additional information from the requesters and consult with others to make sure they fully understand the change and its implications.

One of the common complaints of the CAB meeting occurs as a result of members who don’t adequately prepare and instead waste time during the meeting by reviewing the RFC for the first time. Not only does this waste precious time, it is also disrespectful to the other CAB members who arrive at the meeting fully briefed. This is the prime reason for the cut-off deadline mentioned above – members must be allowed time (and are expected) to properly review change requests prior to CAB meetings.

There are no hard and fast rules when it comes to CAB meeting frequency. Though the most common frequency is weekly, many organizations have several shorter meetings during the week – often tied to release windows.

Other organizations have CAB meetings that are focused on a particular area, such as infrastructure, network or applications. In some cases, it may be desirable to have separate meetings with the business units affected.

The needs of the organization must weigh heavily on the frequency of CAB meetings. Generally speaking, less often can delay needed implementations, while more frequently can consume an inordinate amount of staff time.

Obviously, you should do what makes the most sense for your organization; be aware that how staff respond to the frequency will affect their support for the new change programme. I generally recommend weekly as a good starting point; be flexible and adapt to how the business and IT staff react.

The CAB agenda should include:

• Review new RFCs

• Review changes implemented since the last CAB

• Review proposed standard changes

• Review change schedule

• Consider continual service improvement (CSI) opportunities.

Review RFCs

This is the heart and soul of the CAB meeting – presenting and initial review of proposed changes. Make sure the change requester, key decision makers, and any technical experts representing the change are part of the meeting to answer questions about the proposed change.

Review implemented changes

The CAB should discuss the outcome of each approved change. For any failed or rolled-back changes, the CAB will need an explanation regarding why the implementation wasn’t as expected and determine whether specific follow-up actions are required. Each failed change should be viewed as an improvement opportunity to learn more about the organizational change capability.

Many organizations hold post-implementation reviews (PIR), especially for significant or highly visible changes. This is an excellent practice and should ideally be carried out as part of the project management process, with the results being presented to the CAB to enable improvement opportunities to be assessed.

A PIR is much like a lessons-learned meeting. Its primary purpose is to review the change implementation in depth to determine whether the business outcomes were achieved. PIRs are most often conducted with full representation from IT customers and all key stakeholders.

The PIR should also identify issues or shortcomings during the planning and implementation, and make recommendations for improvements to the process or capability.

It is not recommended that the PIR is only undertaken as a follow up to changes that didn’t go well. Doing so diminishes the value of learning from both successful and unsuccessful changes; it also casts the PIR as a punitive practice applied only to problematic changes.

Review standard changes

Standard changes are an important part of a healthy change management programme. I highly recommend implementing standard changes as early as possible in your change management implementation (see Chapter 5).

If you’re using standard changes, proposed new ones should be reviewed at a CAB meeting in much the same way as normal RFCs are reviewed.

If operational issues relating to an approved standard change arise, the CAB should schedule a review to determine whether the approved process for standard changes requires modification.

In the normal course of CAB meetings, members should be mindful of any normal requests that might be good candidates to be considered standard changes.

Review change schedule

The change schedule is simply a listing of approved changes in a calendar format, and it should be consulted routinely when considering individual changes. It is important to review the overall schedule for any potential conflicts, incompatibility issues and improper sequencing of complex changes.

It is also necessary to ensure major changes are not implemented at times when the organization might be under strain. Be sure to compare change schedules with vacation calendars, staff training course dates or other activities that may impact on resource availability. The organization’s schedules and cycles must also be considered. The CAB should be on the lookout for month, quarter and year-end times, school holidays etc., and also be aware of non-cyclical activities, such as trade shows, conferences, special sales promotions and product launches.

Consider CSI opportunities

Continual improvement is key to a healthy change management programme. This should be a core consideration throughout the process, and the CAB should be on the lookout for opportunities to improve both the change management process in itself and the way the CAB works.

This needn’t be a complex or difficult task. A simple CSI register could be maintained listing ideas for improvements that get prioritized, assigned, and reviewed until implemented.

3.2.6.6 Emergency changes

A well-managed change process should match the rate of change required by the business. In other words, the bulk of changes should fall into the normal or standard category. If an emergency arises, however, it should be dealt with by an eCAB (a subset of the full board), as it might not be possible, or necessary, to gather together the full CAB within the emergency timeframe. The first question an eCAB must ask is, ‘Should this RFC/change really be classified as an emergency or can it be deferred to the next regularly scheduled meeting of the full CAB (in which case, it’s a high/urgent priority normal change)?’

The criteria for emergency change must be kept very high, and always for situations where there is significant and imminent risk to the business. There must always be provision for the special handling of emergency changes.

A closer look: urgent changes

Urgent changes should not be confused with emergency ones.

A very common criticism when adopting formal change management is that it’s slow and bureaucratic rather than being responsive to the needs of the business. While the intent of change management is the exact opposite, this very issue can be a source of significant resistance and frustration, especially if the organization previously implemented changes ad hoc.

The argument is straightforward – whereas a change could previously be applied immediately to support the business, now a change request must be submitted, accepted and queued up for review at the next CAB meeting for approval. This is particularly problematic when the proposed changes resolve pressing issues or implement needed functionality. It may be tempting to use the emergency change provision to accommodate such change requests, but doing so severely undermines the spirit and intent of change management.

A well-established and communicated urgent change provision can take the wind out of these criticisms by providing a mechanism for accelerating the process to respond to unforeseen circumstances so that the business need is met. It is important to include the urgent change provision at the earliest stages of adoption so as to avoid unnecessary cultural resistance.

Urgent or emergency change?

The most common question around emergency changes is: how do you know whether the change you are being asked to approve relates to a real emergency? One of the challenges you face as a change manager is identifying real emergency changes from changes that were simply poorly planned or managed.

Far too often, the emergency change provision is used as a safety valve, of sorts. This misuse often stems from change management being viewed as primarily an IT internal process that stands in the way of doing things quickly. That is not at all the intention of emergency changes, and ramifications of treating it as such are far-reaching and should be avoided at all cost.

Emergency change status is reserved for those situations where there is a significant risk to the business – one that threatens life, financial loss or organizational credibility. A lesser standard opens the door for confusion and misuse.

Some organizations only allow emergency changes when there is a major incident underway and the incident manager is requesting emergency change to remedy a critical business-impacting issue.

This criterion pairs well with a process that treats emergency change requests with drop-everything urgency. It does not pair well with attempting to use the emergency process to compensate for lack of proper planning or simply ignoring the change process.

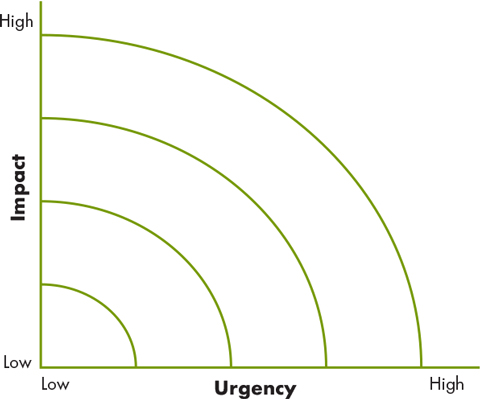

Obviously if there are emergency-level risks, timely resolution is critical. The concept is very similar to the business urgency and business impact chart associated with incident management. The response timeframe is determined by a combination of both urgency and impact.

In practice, change priority is a combination of business urgency and business impact of the proposed change, as shown in Figure 3.2. To be considered as an urgent priority, a change must be both high business urgency and high business impact, but this categorization does not make it an emergency.

Keep in mind that the vast majority of changes are in the planning and development stage long enough to give ample time to follow the normal change process. Urgent changes are those that are truly unexpected and require implementation at the next change window.

As I’ve said many times already, you have to do what makes sense for your organization, but systematic abuse of the emergency change provision will have a significant effect on the viability of the change programme.

Emergency change process

Given the above criteria, it is imperative that the emergency change process be extremely responsive and treats all emergency change requests with the highest level of attention.

Emergency change requests are most frequently submitted by email, phone or in person to the change manager.

Figure 3.2 Change priority

The basic emergency change process is as follows:

• The emergency RFC is submitted to the change manager.

• The change manager immediately considers the request.

• If deemed an emergency, a CAB session (sometimes known as an eCAB) is called immediately.

• The eCAB can meet in person, via phone conference, email or other electronic collaboration method.

• The eCAB reviews the emergency RFC for the same concerns discussed in this chapter for normal changes.

• The eCAB makes an immediate recommendation based on the gravity of the situation and analysis of the risks.

• The change manager approves or denies the change and communicates the decision.

• The approved change is then authorized for immediate implementation.

• As a follow up, the emergency change is scheduled to be reviewed at the next normal CAB meeting (as with any implemented change).

The timeframes must be in alignment with the needs of the organization (government, defence, healthcare, banking and manufacturing all have unique challenges and drivers). Regardless of the business climate, it is best to adopt an emergency change process that more closely resembles a call to the emergency services than the normal change request process. This is for two very good reasons:

• Business outcomes are more important than processes, and a true business emergency demands an IT organization that can respond with changes at the needed pace.

• This level of responsiveness tends to discourage less critical changes from rising to the emergency level.

If your organization has a mature incident management capability – especially with provision for major incidents – you may want to consider delegating emergency change authority to the incident manager when a major incident is declared.

When a true emergency is being managed in this way, the incident manager is already entrusted with significant responsibility on behalf of the company. Because of the severity of the impact on the enterprise, senior business and IT management are involved. By design, decisions are elevated through the incident manager, who is responsible for seeking decisions from the appropriate authority and ensuring timely execution.

With that in place, then, it makes sense that the incident manager and the change manager work in tandem to secure and execute decisions from informed authorities in the organization.

I would only recommend this model for emergency changes in cases where there’s an existing mature incident management capability.

As the change management capability matures, the number and percentage of emergency changes should be tracked as KPIs and kept to a minimum (exact percentage to be determined by the organization).

eCAB

Emergency changes are reviewed on an accelerated timeframe by the eCAB.

The eCAB can be an emergency call of the normal CAB membership, or it can be a completely different group. Either way, the personnel must be available at a moment’s notice. Members are expected to leave meetings and drop normal workday tasks when it is convened.

In addition to the ability to assess technical risks and issues, eCAB members must also be able to assess business risk and impact. The eCAB is often heavily staffed with senior leaders and managers who are responsible to the organization for the management of business risk.

The change manager ensures the right senior management are on hand to address business risk and weigh in on the proposed change(s). This is important to ensure the actions of the emergency change are in alignment with the best interests of the company.

The eCAB must not allow the urgency of the situation to cloud their judgement in evaluating the proposed change for risks and unintended consequences, and they must determine whether the proposed change is likely to achieve the required outcome.

3.3 Metrics/KPIs

To ensure change management achieves the desired results, clear metrics must be established and regularly reported and reviewed. These operational metrics are intended to highlight the need for corrective action or directional changes in the change process.

Before metrics can be established, we must identify some higher-order objectives that the change management programme is seeking to deliver. These objectives form the CSFs and usually flow directly from the change policy’s explicit objectives.

By nature, there should be a limited number of CSFs – generally two or three (and not more than four). ‘Critical’ in this case means those few core factors that determine success; they are generally objectives specified by senior management. The term ‘critical’ is used to indicate that CSFs are not broad, generalized statements of desired results; they are those determined to be vital to the organization and are, therefore, more important than other measures that may also be desirable.

CSFs are directional and can be quantified. They are not metrics themselves, but rather statements of desired direction, often involving the reduction or increase of a certain element, or an improvement of something in a stated direction. It is important to establish CSFs that are specifically suited to your organization, that support the current requirements of the business.

KPIs, by contrast, are selected to measure how well the process is supporting the desired outcomes (CSFs). In other words, KPIs are chosen to measure whether a CSF is being achieved (or not).

What is a KPI?

Key performance indicators (KPIs) are derived from established high-level critical success factors (CSFs) – those few core elements that must be in place in order to be able to judge whether a process is successful.

A small set of KPIs are established for each CSF. The operative word is ‘key’ – indicating that this particular measure has been determined to be a key indicator in support of the CSF. KPIs are quantitative and measure elements that indicate whether the process is moving closer to the CSFs or further away.

Together, CSFs and KPIs establish directional objectives and quantitative measures to demonstrate process performance in that direction.

3.3.1 Sample metrics for phase 1

Let’s examine some reasonable objectives for phase 1. Keep in mind that you want to measure what’s important in your organization at this particular point in time. Both CSFs and KPIs will change with time, experience and maturity.

In the first phase, it is important to establish objectives that work as CSFs. Under each of these, I’ve added some suggested KPIs that help quantify achievement of that objective:

• CSF 1 Increase changes managed by new change process

• KPI 1 Increase in changes reviewed by the CAB (percentage)

• KPI 2 Reduction in unmanaged changes (percentage)

• KPI 3 Increase IT staff satisfaction with change process (favourable survey results)

• CSF 2 Reduce negative business impacts relating to changes

• KPI 1 Reduced number and percentage of change-related incidents

• KPI 2 Reduced business impact of change-related incidents (number and duration)

• CSF 3 Ensure cultural adoption

• KPI 1 Increase in changes that provide proper documentation for support staff (number and percentage)

• KPI 2 Decrease in the number of unauthorized changes (those that bypass the change process)

• KPI 3 Increase in satisfaction of change management for IT staff and end users (favourable survey results)

• CSF 4 Manage IT environment without bureaucracy

• KPI 1 Increase in changes completed in time and with estimated resources (number and percentage)

• KPI 2 Increase in changes that delivered expected business outcomes (number and percentage)

• KPI 3 Increase in customer satisfaction for change management from the project management office (PMO) and end customers (favourable survey results)

• KPI 4 Reduction in number and percentage of urgent and emergency changes.

Note that KPIs can support multiple CSFs. Target goals should be established for each of the key areas. In this initial phase, I would highly recommend target goals that increase over time. For instance, you may establish a goal for changes managed by the CAB to be a 50% increase, followed by an additional 50% once achieved.

Stepping of targets is fundamental in a continual improvement approach – take small, achievable steps, and celebrate success, to build support and momentum for the programme.

3.3.2 Reporting

Regular reporting of the CSFs and KPIs are important to demonstrate early results and maintain ongoing support for your new change management programme. It’s helpful for cultural adoption in that it demonstrates in tangible numbers how well the programme is working.

If staff or customers feel the new change programme slows down project delivery or doesn’t produce results – even if it’s only a perception – it fuels resistance to the new programme.

Starting with the very first adoption efforts, I encourage monthly reporting to senior IT management and key business stakeholders. Early and frequent reporting demonstrates transparency and encourages engagement in improvement efforts. Reporting should be focused on progress achieved and challenges faced – and include details of corrective actions needed to stay in alignment with stated objectives.

Reporting should never be allowed to become a finger-pointing activity. Notice that I’m not suggesting sorting compliance by individual teams.

3.4 When to begin phase 2 (success criteria)

How do you know when you’re ready to move on to phase 2? If you already have a ‘phase 1’ programme in place, how do you know you’re ready to mature it?

Recall that our phase 1 objectives had to do with successful programme adoption; briefly:

• Introduce change control

• Show early results, demonstrating value to the business

• Ensure cultural adoption

• Manage the IT environment while minimizing:

• Bureaucracy

• Unnecessary delays

• Organizational resistance

• Set the stage for future maturity.

3.4.1 Metrics stabilization

The first sign that you may be ready to think about phase 2 is when you are consistently meeting the targets for metrics. Each company has its own unique culture, so it’s hard to know exactly when that’s been achieved, but in general, you’re looking at those KPIs specified in section 3.3.1 and seeing target numbers and percentages achieved or even exceeded, plus positive feedback from the various stakeholders in the change management process.

3.4.2 Cultural acceptance

There is more to success than just metrics performance, however; you need to determine the state of the culture – which is hard to do with pure metrics. Regular surveys of IT staff and customers are important to gauge satisfaction with and engagement in the change programme. If staff are showing signs that they’re getting tired of the new change programme, and there’s a growing resentment, you’re probably not ready to proceed to phase 2.

In the early stages, increasing the number of changes that go through the new change programme is a key factor. It’s not unlike a parent holding a child’s hand as they’re learning to walk. Gradually, over time, the parent holds on less and less, eventually leading to that moment when the child walks with no parental assistance. Just like the child, your new change programme will have some falls and setbacks. Some of them may even be painful.

Signs that your change programme is starting to have legs include the enthusiasm with which changes are reviewed, and the collaborative spirit of the CAB members. Be on the lookout for staff who want to make improvements that increase the quality of the process (which is very different from suggesting that you stop doing change management!). When staff see the value of change management to the point they want to see it improve, you’re well on your way to the next phase.

3.4.3 Business value

One of the key measures of phase 1 success is when the business recognizes the improvement in change execution and reduction in negative impact. The support generated because the business is noticing improved results from the change initiative does wonders for getting the support needed to move on to the next phase.

Show value before doing more

In general, it’s always best to be successful in a small thing before moving to a bigger thing. Change management is no different. This is why it is so important to show early results on the investment you’re making in change management. If your results are limited or marginal, or worse – poor results, or a reputation for slowing down delivery – you’re going to have an uphill battle getting support for further improvements in the dubious change programme.

Value is always in the eyes of the beholder, which in this case is the organization. If only IT is convinced of the value of change management, it can be argued that it has no tangible value. Harsh as that sounds, it is always the customer who determines the value of what they receive in the way of service.

3.5 Chapter 3: key concepts

The key concepts in Chapter 3 can be summarized as follows:

• Start with a basic ‘phase 1’ process to ensure successful adoption.

• Introduce the concept of change control.

• Establish a weekly CAB review and select the right CAB members.

• Manage and monitor cultural acceptance.

• Measure adoption milestones and progress.

• Plan to show early results against organization needs.

• Create a change policy that clearly describes change management expectations.

• Establish a procedure for handling emergency changes.

• Move to phase 2 (see Chapter 4) when the organization is ready.