Chapter four. Development

Development is a core concept of the systems view of the world. In contrast to the mechanistic and biological views concerned respectively with efficiency and growth, the systems view is basically concerned with development. Development is a creative and learning process by which a social system increases its ability and desire to serve both its members and its environment by constant pursuit of truth, plenty, good, beauty, and liberty. The two major components of development, therefore, are desire and ability. But neither desire nor ability alone can ensure development. Those who are awed by their environment and place the shaping forces of their future outside of themselves do not think of voluntary or conscious change, no matter how miserable and frustrated they are. Without a shared image of a more desirable and exciting future, life proceeds simply by setting and seeking attainable goals, which rarely escape the limits of the familiar.

Keywords: Ability; Adaptation; Aesthetics; Antagonistic; Chaotic complexity; Chaotic simplicity; Classical; Cultural boundaries; Cybernetics; Desire; Deterministic; Differentiation; Ethnocentrism; Innovation; Integration; Interactive; Multifinal; Neoclassical; New-left; Organization; Organized complexity; Organized simplicity; Orthodox Marxism; Oscillation; Participation; Plurality; Radical humanism; Radical Weberianism; Singularity; Socialization; Structural functionalism

Development is a core concept of the systems view of the world. In contrast to the mechanistic and biological views concerned, respectively, with efficiency and growth, the systems view is basically concerned with development.

A critical review of major traditional views of development suggests that they are generally characterized by problems of (1) ethnocentrism, (2) unidimensionality, and (3) deterministic perspective.

In the first place, most developmental theories have built-in ethnocentric biases. The models, as ideal types of developed societies, bear unmistakable signs of the western historical experience. Furthermore, the fragmentation of developmental theory into competing disciplinary perspectives results in a unidimensional view of development. Each discipline tends to exclude the other variables from its own unique domain of analysis — material quantities in economics, power in political science, and order in sociology.

Perhaps the most serious problem lies in the fact that most developmental theories begin with a preconceived law of social transformation. Assumed to be true at all times and in all environments, the path is charted beforehand.

Development plays a central role in the systems view of the world, therefore, it is important to clarify any misconceptions that exist about the nature of development and the properties usually identified with it.

Although it is risky to lump developmental theories together, for practical purposes we need some kind of classification scheme. Still, important differences and some significant continuity exist among them. Further, these theories do not necessarily refute each other. In most cases, they either complement or supersede one another.

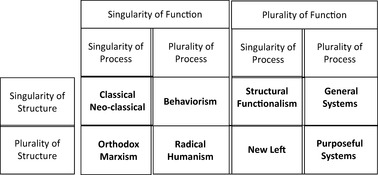

The typology presented here (Figure 4.1) categorizes developmental theories into eight types depending on their underlying assumptions (explicit or implicit) regarding the singularity or plurality they attribute to function, structure, and process.

Singularity refers to theories in which a particular structure, function, or process is considered fixed and/or primary in all environments. Plurality refers to theories that consider structure, function, or process to be multiple and/or variable in the same or different environments.

Note that the theories in category 1 (singularity of function, structure, and process) are descriptive and do not deal with any means of intervention. Other categories, by assuming plurality in at least one dimension, provide for some means of intervention. Category 8 (purposeful systems, representing the systems view of development) assumes plurality in all three dimensions: function, structure, and process. Therefore, category 8 is an inclusive theory. It provides a framework to explain the other seven categories as special cases. The following scheme summarizes the assumptions and the main features of each type and their perspectives on development.

4.1. Schematic view of theoretical traditions

Without explanation, the significance of the typology presented in Figure 4.1 may be lost. This section addresses each element in an attempt to differentiate them.

Singularity of Function, Structure, and Process

Model: Determined, mechanistic, and descriptive model of man in a state of nature, homo-economicus; forms social contract to increase wealth through increasing productivity and division of labor.

Theoretical Tradition: Classical and neoclassical, as exemplified by the writings of Smith, Ricardo, Malthus, Mill, Marshall, Keynes, Schumpeter, and Rostow.

Development Process: Stability and growth against major constraints of capital accumulation, population growth, and limited natural resources; automatic mechanism of adjustment. Keynes introduces the principles of conscious manipulation of productive forces (neoclassical) to maintain stability and growth. Rostow considers a stage theory, traditional, pre-take-off, take-off, self-sustaining growth, and high mass consumption.

Singularity of Function and Process with Plurality of Structure

Model: Deterministic and mechanistic model based on linear cause-and-effect relationships. Conflict, the prime producer of change, results in a stage theory and formation of a new social structure.

Theoretical Tradition: Orthodox Marxism and radical Weberianism, as exemplified by the writings of Engels, Lenin, Kautsky and Plekhanov, Weber, Dahrendorf, and Rex.

Development Process: In orthodox Marxism economy is the prime function, and class struggle is the prime process. Historical determinism is about moving from primitive communism to ancient slave societies, feudalism, capitalism, socialism, and finally the ideal of communism (classless society) through class conflict and progressive system transformation. In radical Weberianism, power is the prime function, and the legitimization is the prime process. Varying structure is defined by authority and classified into three pure types to correspond with different types of society: traditional, charismatic, and rational-legal. There is increasing rationalization of authority from patriarchal to patrimonial to feudal and modern society moving toward an ideal type of bureaucracy (frictionless machine). Dahrendorf sees the interest of the power holder as so clearly distinct from the interest of the powerless that conflict becomes the permanent feature of social life, with varying degrees of effect, ranging from revolution to small-scale reform.

Singularity of Function and Structure with Plurality of Process

Model: Input/output (stimulus-response) model of human and social behavior (environmentalism); an organic model that uses deviation amplification or positive and negative feedback loops to change.

Theoretical Tradition: Behavioral, as exemplified by the writings of Watson, Skinner, Erikson, and Lasswell.

Development Process: Increasing order through induced motivational and behavioral change. Sublimation of the destructive instincts into creative work, and finally formation of a world culture shaped by “behavioral technology,” which is needed for survival. Watson places the central emphasis on controlling behavior through learning, which, he believes, could be achieved by the principle of “conditioning.” Skinner suggests that freedom is an illusion that man can no longer afford. He claims that behavior can be predicted and shaped exactly as if it were a chemical reaction. But for Erikson, physical, social, cultural, and ideational environments are partners to biological and psychological innate processes.

Singularity of Function with Plurality of Structure and Process

Model: There is no absolute above man that could re-create the social order in which he/she lives. Emancipation of man is the prime function, whereas process and structure are seen as multiple and variable.

Theoretical Tradition: Radical humanism, as exemplified in the writings of the early Marx, Marcuse, Lukacs, Sartre, Fromm, Gramsci, and the Frankfurt School.

Development Process: Changing the social order through a change in mode of cognition and consciousness. Release from the constraints the existing social structure places on human development. The emphasis is on modes of domination, emancipation, deprivation, and potentiality.

Singularity of Structure and Process with Plurality of Function

Model: Biological, integrated, and dynamic equilibrium model; multiple functions to maintain an unstable but fixed structure (steady state) through the prime process of homeostasis; representing analytical, positivistic, and empirical view of the world.

Theoretical Tradition: Structural functionalism, as exemplified by the writings of Comte, Spencer, Durkheim, Parsons, and Eisenstadt.

Development Process: Integration, adaptation, goal attainment, and pattern maintenance are regarded as the four functional imperatives for a social system's continuing existence and evolution toward maturity and growth.

Plurality of Function and Structure with Singularity of Process

Model: Multifunctional, organic, and nonlinear cause-and-effect relationships. Conflict is considered to be the prime producer of change. Varying structure “over-determined” by interaction of economic, political, ideological, and theoretical subsystems of totality.

Theoretical Tradition: New-left, as exemplified in the writings of Althusser, Poulantzas, Della-Volpe, and Colletti.

Development Process: Increased integration, through law of “uneven and combined development,” “method of successive approximation,” “fact of conquest,” and increased accumulative knowledge of mankind with regard to nature.

Plurality of Function and Process with Singularity of Structure

Model: Holistic, open, multi-loop feedback and input/output model of social systems. Biological analogy is used to search for the underlying regularities and structural uniformity.

Theoretical Tradition: General systems theory and cybernetics, as exemplified by the writings of Bertalanffy, Ashby, Miller, Beer, and Bogdanov.

Development Process: Equifinal, neg-entropic processes moving toward organized complexity. System change through learning, adaptation, and induced motivational and behavioral change.

Plurality of Structure, Function, and Process

Model: Purposeful, sociocultural, information-bonded systems. Capable of redesigning themselves by new functions, structures, and processes creating new modes of organization at the higher levels of order and complexity.

Theoretical Tradition: Systems view (third generation), as exemplified by the writings of Ackoff, Boulding, Buckley, and Churchman.

Development Process: Multi-final, interactive, and purposeful movement toward increased differentiation and integration. A learning and creative process to increase ability and desire to re-create the future. An ideal-seeking mode of organization to resolve conflicts at higher levels. Systemic view of development, by accepting plurality in all three dimensions of function, structure, and process; considers the other seven categories as special cases. From the systems perspective, development is not only a multifunctional phenomenon, but it involves multiple and varying concepts of structure and process as well.

4.2. Systems view of development

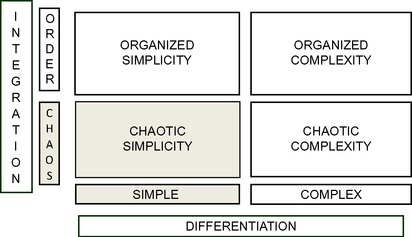

Development of an organization is a purposeful transformation toward higher levels of integration and differentiation at the same time (as represented in Figure 4.2). It is a collective learning process by which a social system increases its ability and desire to serve both its members and its environment. Differentiation represents an artistic orientation (looking for differences among things that are apparently similar) emphasizing stylistic values and signifying tendencies toward increased complexity, variety, autonomy, and morphogenesis (creation of a new structure). Integration, on the other hand, represents a scientific orientation (looking for similarities among things that are apparently different) emphasizing instrumental values and signifying tendencies toward increased order, uniformity, conformity, collectivity, and morphostasis (maintenance of structure).

Depending on the characteristics of a given culture, a social system can move from a state of chaotic simplicity toward organized simplicity, which is produced by emphasizing integration at the cost of differentiation. It can also move toward chaotic complexity produced by increased differentiation at the cost of integration or it can move toward organized complexity, signifying a higher level of organization achieved by a movement toward complexity and order concurrently. This means that for every level of differentiation there exists a minimum level of integration below which the system would disintegrate into chaos. Conversely, higher levels of integration require higher degrees of differentiation to avoid impotency.

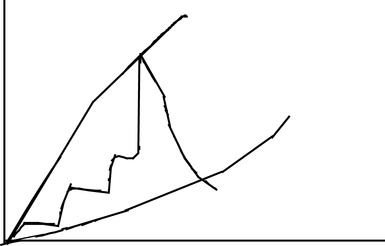

Within the boundaries of a given culture, a variety of different orientations exist. The presence of a “left” and a “right” in every social group and political party is the manifestation of this phenomenon (Figure 4.3).

In a flexible social setting, oscillations of low amplitude occur within the cultural boundaries without disruption, as demonstrated by periodic shifts of government between the Labor and Conservative parties in the United Kingdom or the Democrats and Republicans in the United States. However, if an orientation tries to cross the limits of the cultural line, a powerful reaction will move it back to the other extreme, producing further oscillations and cusping into a change of phase. Unfortunately, in societies polarized by antagonistic and rigid ideologies, social transformation takes place by a violent change of phase (a cusp). Retrieval from such a situation is often extremely problematic, since the relationship between members is irreparably damaged, as happens in societies that are thrown into a perpetual state of civil disorder.

Development of social systems is a transformation into successive modes of organization. Each mode is a whole, characterized by higher degrees of both integration and differentiation, and is potentially capable of dissolving lower level contradictions by converting them into contraries. In contrast to physical systems whose energy level determines their mode of organization, in social systems the knowledge level defines the mode. The role of knowledge in social systems, therefore, can be said to be analogous to that of energy in physical systems. The significant point is that knowledge, unlike energy, is not subject to the first law of thermodynamics (the law of conservation of energy). One does not lose knowledge by sharing it with others. On the contrary, its dissemination increases the knowledge level of the social system and helps the creation of new knowledge. It is this capability that enables a social system of its own accord to constantly re-create its structure and redefine its functions.

In defining development, we identify two active agents: desire and ability. Desire is produced by an exciting vision of a future enhanced by the interaction of creative and recreative (joyful) processes. The creative capacity of man, along with his/her desire to share, results in a shared image of a desired future. This generates dissatisfaction with the present and motivates pursuit of more challenging and more desirable ends. Otherwise, life proceeds simply by setting and seeking attainable goals, which rarely escape the limits of the familiar.

Unfortunately, for some religions, the fundamentalist interpretation regards creation as a sole prerogative of God. Human beings are not allowed to engage in any act of creation. Art in almost any form — whether painting, sculpture, music, or drama — is prohibited. Recreation (enjoyment) is also considered sinful. This antagonistic attitude toward aesthetics militates against development, because it does not provide much opportunity to articulate and expand one's horizon beyond the immediate needs of mere existence. This self-limitation provides one explanation for cases of underdevelopment despite the availability of vast resources.

Dissatisfaction with the present, although a necessary condition for change, is not sufficient to ensure development. What seems to be necessary as well is a faith in one's ability to partly control the march of events. Those who are awed by their environment and place the shaping forces of their future outside of themselves do not think of voluntary or conscious change, no matter how miserable and frustrated they are.

Ability, therefore, is the potential for controlling, influencing, and appreciating the parameters that affect the system's existence. But ability alone cannot ensure development. Without a shared image of a more desirable future, the frustration of the powerful masses can easily be converted into a unifying agent of change — hatred — that in turn will successfully destroy the present but will not necessarily be a step toward creating a better future.

Central to this notion of development is its distinction from growth. According to Ackoff:

They are not the same thing and are not even necessarily associated. Growth can take place with or without development, and development can take place with or without growth. A cemetery can grow without developing. On the other hand, a person may continue to develop long after he or she has stopped growing, and vice versa. A person can build a better house with good tools and materials than he/she can without them. On the other hand, a developed person can build a better house with whatever tools and materials he/she has than a less-developed person with the same resources. Put another way: a developed person with limited resources is likely to be able to improve his quality of life and that of others more than a less-developed person with unlimited resources. Constraints on a system's growth are found primarily in its environment, but the principal constraints on a system's development are found within the system itself.

Gharajedaghi and Ackoff (1984)

To understand the process of development of a social system we have to deal with structures and the processes that help or limit the creation of collective desire and ability for the pursuit of its ends. The parameters that coproduce the futures are found in the interaction of the five dimensions of social systems: wealth, knowledge, beauty, power, and values. Compatibility among these five dimensions defines the effectiveness of the emerging mode of organization. This mode of organization determines the level of integration, and the collective ability of the members to create the future they want. This means that a minimum level of integration is required if the aggregate of individuals is to function as an effective system. Ironically, the prime concern of every organization theory has been to define the criteria by which the whole is to be divided into parts. Major theories have implicitly assumed that the whole is nothing but the sum of its parts and have conveniently ignored the fact that effective differentiation requires incorporation of a means that would integrate the differentiated parts into a cohesive whole. In this regard, the classical school of management depends solely on the unity of command and the imperative of no deviation. At the opposite end, advocates of free markets rely on the assumption that perfectly rational micro-decisions would automatically produce perfectly rational macro-conditions. Both approaches fall short because they fail to recognize that effective social integration requires that compatibility among the members be continuously and actively re-created. Ultimately, the level of integration and development that an organization will achieve depends on the means by which it deals with interaction among its members.

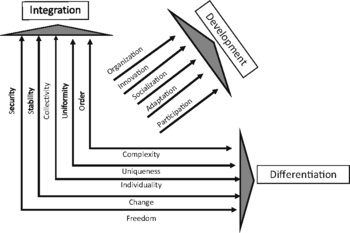

Differentiation poses little challenge because it is the very nature of social systems to become different from each other. From families to cities and nations, groups of people can usually describe with ease how “we're different or unique.” Integration, however, requires skill to accomplish. To integrate one has to appreciate the systemic nature of the interactions between opposing tendencies. For example, security and freedom, usually considered dichotomous, are actually two aspects of the same phenomenon. Freedom is not possible without security and security makes no sense without freedom. But if we choose to deal with each one of these aspects separately, then we should not be surprised to find them in conflict. The easiest solution to security, if treated in isolation, would be to limit freedom, and that of freedom would be to undermine security. Despite seemingly contradictory requirements for pursuit of opposing ends, there are processes that would make the attainment of both ends feasible. For instance, both freedom and security are attainable by a process called participation, stability and change by adaptation, and order and complexity by organization. Similarly, production and distribution of wealth form a complementary pair. Without an effective production system, there can never be an effective distribution system. To fail to note this important interdependency is to leave out the most important challenge of the problem. An obsession with distribution without a proper concern about production will result in nothing but an equitable distribution of poverty. Preoccupation with production without a similar concern for an equitable distribution will lead to an alienated society.

The emerging tendencies — innovation, learning and adaptation, socialization (parity), participation, and organization — cannot stand alone. Together they form the whole, and coproduce a process called development (Figure 4.4). The holistic view of societal development requires that all of the five social functions — the generation and dissemination of knowledge, power, wealth, value, and beauty — develop interdependently, utilizing all of the five complementary processes outlined earlier.

4.3. Obstruction to development

Obstructions to development of a social system can be viewed as malfunctioning in any one of the five dimensions. Scarcity, maldistribution, and insecurity in any one of the five social functions (i.e., generation and dissemination of knowledge, power, wealth, values, and beauty) are considered primary or first-order obstructions. Alienation, polarization, corruption, and terrorism are among social phenomena that represent secondary or second-order obstructions (Table 4.1).

Second-order obstructions are coproduced by the interaction of primary obstructions. Dealing with primary obstructions is beyond the scope of this book. Interested readers will find a full discussion of these concepts in A Prologue to National Development Planning (Gharajedaghi and Ackoff, 1986). However, since the second-order obstructions — alienation, polarization, corruption, and terrorism — are very much part of our present reality a brief discussion of these four phenomena may be in order.

4.3.1. Alienation

A social system in its ideal form is a voluntary association of purposeful members, so that emigration of a member from the system is considered to be the highest manifestation of his/her protest. But because of a series of self-imposed or external constraints, a dissatisfied member is not able to leave the system. He/she therefore becomes alienated from the very system of which he/she is supposed to be a voluntary member.

The underlying causes of alienation can be found in the interactions of the following primary obstructions.

• Powerlessness. Powerlessness is equivalent to ineffectualness and impotency. When an individual feels that her/his contributions to the group's achievements are insignificant or she/he cannot influence the behavior of the group of which she/he is a member, gradually a feeling of indifference sets in and the individual loses interest in the group.

• Rolelessness. Incompetence or lack of the necessary knowledge to carry out responsibilities of one's accepted role results in excessive anxiety and frustration.

• Meaninglessness. Lack of excitement in life and insensitivity toward the creative and recreational aspects of being most probably will result in a feeling of meaninglessness.

• Exploitation. When individuals or a group feel that they have been deprived of their fair share of a system's achievements, feelings of injustice will set in and harmful hostilities will result.

• Conflicting value system. As mentioned before, the extent to which an individual's value image coincides with the shared image of her/his community determines the degree of his/her membership in that community. An extreme difficulty arises when an individual needs to be a member of two communities with conflicting value systems. The level of integration that a society will achieve depends on the means by which it dissolves the value conflict among all of its diverse membership groups. For sure this challenge cannot be met by just a legalistic approach as the following example demonstrates.

In a recent study a group of my graduate students observed that young African Americans are caught in an impossible dilemma. To be accepted by their community and peers as a member they have to demonstrate that they are not playing the white man's game. But “not playing the game” or deviation from the norm has a huge price tag. It is usually punished harshly and disproportionally to the degree of the harm it has caused the society. Unfortunately, the likes of Colin Powel, Condoleezza Rice, Oprah Winfrey, Bill Cosby, and many success stories do not seem to be the role models for the young African Americans. Accused of playing the white man's game, they might not even be considered true members of the black community. This unfortunate second-order obstruction has resulted in a vicious circle that undermines development of otherwise talented black communities. Appreciating this conflict can help us understand why a phenomenal basketball player with all the apparent success and popularity sometimes has to come across as a “bad boy” to keep his membership in his own community as well.

4.3.2. Polarization

The formation of highly polarized groups around conflicting ideologies is perhaps one of the most destructive obstructions to development. Polarization usually takes the form of religious versus secular tendencies with each further divided into left and right orientations. This polarization is further reinforced by ethnic conflicts and “divide and rule” strategies of politicians. In their struggle for fame and power, self-serving and cynical intellectuals manipulate the masses with demagoguery — pulling them from one extreme to the other like a pendulum. The problem is that none of the so-called opposing groups is strong enough to govern without the cooperation of the others, and yet each one is powerful enough to disrupt and undermine the effectiveness of the ruling group. This is partly due to increased complexity in the system, making it more vulnerable to sabotage on the one hand and difficult to manage on the other. Hatred of the ruling group usually becomes the unifying agent of change. Another cycle begins with opposing forces regrouping. The oscillation will not end until opposing ideologies learn to modify their dogmatic positions, give up their monopolistic claim on power, and work toward creating a shared image of a desired future through processes of integration — not at the expense of differentiation, but alongside it.

The critical issues of qualitative change and the need to deal more effectively with social pathologies demand incorporation of second-order learning in social systems. This requires the creation of a new mode of organization in the form of an ideal-seeking system, in contrast to an ideal state. This warrants further clarification.

Throughout history there have been repeated attempts to fashion human societies in accordance with some sort of idealized image. This has been done by prophets, philosophers, social reformers, and in recent times by the state apparatus in more than one country. In all cases, these ideals have been defined by human authorities that have attempted to legitimize their authority by means of an ultimate authority such as science or God. But the identification of the ideal state with an ultimate authority precludes freedom to change. This is the essence of social pathology that in a social context is defined as inability to change.

Within this framework of acceptance of an ideal state defined by ultimate authority, it is possible to distinguish between two approaches. The first approach consists of specifying a detailed and comprehensive set of rules of conduct for individual behavior which, if followed by all members of society, would automatically lead to the emergence of the ideal state. In the name of ultimate truth, the objective of this approach has been the creation of a “new man” who will better conform with their image of ideal society. Ironically the repeated failures in changing the “nature of man” into a preprogrammed robot has not reduced the commitment of “true believers” in their pursuit. On the contrary, enjoying a phenomenal capacity for denial, they blame the weakness of the man for the failures and see an urgent need for total control by establishment of a totalitarian order. The second approach is characterized by the struggle to create a new social structure based on the assumption that man is solely the product of his/her environment and that his/her behavior is basically a reaction to it. Scientific socialism, which represents the first attempt of this approach, degenerated in practice into the first type once it was realized that proper structure (Weberian bureaucracy) failed to produce the expected outcome.

The fundamental problem with both of these approaches, which despite their apparent differences result in the same practical consequences, is in their misconception of the nature of the ideal state and the processes that bring it about. They both contend that

1. There is one and only one end (ideal state) predefined by an ultimate authority (God or science).

2. The ideal state is not only attainable, but the movement toward it is also inevitable.

The inevitability of the final state, and its independence from the generating processes, leads to the notion that “the end justifies the means.” It is assumed that the seizure of power by the chosen class or group is a precondition for its realization.

But, ideals, in the systems view, are regarded as dynamic and changing over time. The shared image of a desired future, defined by the members of the social system, reflects the spacio-temporal realities (here and now) of the particular historical moment, and thus is alterable even before being approached (moving target). By considering man as a purposeful system, with choice of both ends and means, the systems thinking rejects efforts aimed at degrading him to the level of a robot. The recognition of the element of choice in the behavior of social systems leads to the belief that these systems have the capability of selecting their own future and successively approximating it by choosing appropriate means. In the systems view every phenomenon is the result of chosen processes; thus, to bring about the desired end it is necessary to choose appropriate processes for its attainment. For example, means that negate the end cannot be effective in bringing it about. Creation of a hero to champion the cause against heroism is a self-defeating proposition. The means are among coproducers of the end, directly influencing the essential qualities of the resulting phenomenon.

4.3.3. Corruption

Corruption is not just malfunctioning of the value system, but a second-order obstruction. It is the result of structural defects in more than one dimension of social systems including generation and distribution of power, wealth, and knowledge. To carry out its vital functions, a social system must be organized. The way a social system is organized determines its ability to overcome the obstructions it faces. In this context a social pathology is produced when an obstruction to development benefits those who are responsible for removing it. Unfortunately, bureaucracy represents a pathological mode of organization where an organized interest group benefits from the obstructions it has created. For instance, the more complex a bureaucratic process can be made, the more staff is required to manage it and the larger and more controlling the administering agency becomes. In addition, the present level of interdependence and complexity demand a higher level of sophistication that far surpasses the known capabilities of the present bureaucratic system. Under these conditions, only a source of power outside the bureaucracy can create movement within the system. Therefore, individuals will seek out and support these external power sources. In time, the hierarchy of powerful patrons demands certain rewards in exchange for their valuable support. This reward structure allows corruption to spread throughout the entire system, ultimately becoming a justifiable way of life.

Charles Handy, in an interesting article, “What Is a Business For?” (Harvard Business Review, 2002) makes a serious observation regarding recent corporate practices:

The current disease is not just a matter of dubious personal ethics or of some rouge companies fudging the odd billion. The whole business culture of our current Anglo-American version of stock market capitalism may have become distorted. We can see with hindsight, that in the boom years of the 1990s America had often been creating value where none existed, bidding up the market capitalization of companies to 64 times earning, or more.

If one takes this argument to its logical conclusion it would reveal that corporate America is facing two critical challenges. The first challenge concerns the effectiveness of corporate governance. The absentee shareholders whom Charles Handy calls “gamblers” or investors are supposed to elect the members of the board of directors. Most of these gamblers do not have any long-term commitment to the entity in which they hold shares. Today his/her interest might be in X Corporation, but no one knows where it will be tomorrow. It might even find its way in to the Y Corporation that is a direct competitor of X. In reality the boards are virtually appointed by the management they are supposed to control. They usually re-elect the CEO who has placed them on the board in the first place.

The second challenge is produced by the tremendous pressure to manage for the short term. Unless the reports of the next quarter meet the expectation of the stock market for another double-digit growth performance, the overrated stock price will tremble and the gamblers will start to sell off the stock. Under this kind of pressure devious behavior will be the norm rather than the exception.

4.3.4. Terrorism

Terrorism is perhaps the single most critical obstruction to development of a peaceful international order. It is a second-order obstruction that has most of the primary obstructions — poverty, disparity, deprivation, powerlessness, hopelessness, discrimination, ignorance, hatred, and fanaticism — as its coproducers. And yet there is no agreement on its operational definition. One person's terrorist is another person's freedom fighter.

However, irrespective of where one is coming from, there is no question that terrorism is based on the false assumption of the “zero-sum game.” In a zero-sum game the total sum of winnings and losses add up to zero. If you lose I will win, and vice versa. As systems get more sophisticated they become increasingly vulnerable to the actions of the few. Making the other side lose becomes easier than trying to win. This is why terrorism becomes the favorite means of weaker sides when confronting stronger enemies. Therefore, to get a handle on terrorism I propose we look at it as a means to an end.

The ends in this context seem to fall into one of three categories: revenge, cry for help, or ideological battle. The tragedy of Oklahoma City is an example of terror as a means of revenge. Revenge is a random act difficult to detect. A cry for help, on the other hand, represents the struggle of desperate people trapped in an unfortunate, unjust politico-economic mess. This type of terrorism is a reflection of sustained frustration of a people to deal with their humiliating powerlessness through normal channels. The most effective way to stop this type of terror is to dissolve the paralyzing impasse.

The bombing of abortion clinics is an example of terrorism in an ideological battle. The ideological terrorism in all of its manifestations — secular left or religious fundamentalism — has used intimidation and random terror to impose their value systems or preferred way of life on the population at large. The strategy is based on the assumption that to paralyze people one should make them feel guilty and insecure. This type of terrorism usually needs a powerful enemy to hate. Hate, converted to need, becomes a way of life. It is used to produce goal-seeking robots. These robotic, true believers are capable of brutality incomprehensible to normal human beings. Unfortunately, the first and second types of terrorists become foot soldiers for the third type.

In light of the ideological vacuum created by the collapse of communism, various forms of fundamentalism have gained momentum and are growing noticeably all over the globe. Among these groups, the one that generates the most concern is the movement with an unshakable faith that a secular style of life is “corruption on the earth.” This movement is against beauty, happiness, choice, pluralism, and freedom. Its followers oppose all values that have made the world a better place to live.

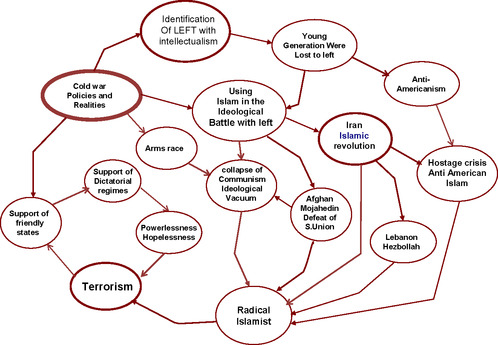

Unfortunately, in the late 1970s religious fundamentalism got a tremendous boost from American policy in the Middle East. After World War II, despite winning the war, America found herself losing the ideological battle. For years leftist ideology had become synonymous with intellectualism. In most of the third world, the youth were lost to the leftist movement. The U.S. administration at the time, working on the assumption that the only way to combat an ideology is with another potent one, decided to engage Islam in the ideological battle with communism. America created the Mojahedin to counter the Soviet Union's invasion of Afghanistan and supported other Islamic movements in the region. Ironically, after sensing a strong anti-American sentiment in the Middle East some of these movements, with a Machiavellian move, decided to identify their version of Islam with anti-Americanism. This tag was needed to promote their cause in the vulnerable countries of the region. Figure 4.5 captures the interaction of two reinforcing feedback loops. Note how the first loop generates radical Islamists and the second one converts them to terrorists.

The network of nationless fundamentalists, unhappy about progress of women toward equality and freedom, pose a dangerous threat to all of humanity. These true believers are ready to use any kind of intimidation and brutality to keep their women subordinate and under control. To dissolve this mess is a human rights obligation. It should be treated above partisan politics and competing economic interest. Nothing short of the uncompromising commitment and determination of the whole international community to support the development and formation of civil societies will do the trick. Acceptance as a member of the world community must be contingent upon accepting and forming a civil society. In the age of globalization no nation can afford to be left out of the world community. This fact is the most practical means of dissolving this mess we now face. It provides the strongest motive for the development of civil societies.

The civil society is a secular state that cannot endorse any religion or ideology. The basis for its authority is in man-made law, not in religious doctrine, divine revelation, or a secular deity. Freedom of religion — including freedom from religion — and the freedom not to believe in any deity, are preconditions to the formation of a pluralistic order, where the majorities that are not capable of protecting the rights of minorities do not deserve to govern.

Dire as the current world situation may be, this chapter ends not in desperation, but in the belief that interactive design of sociocultural systems offers practical and positive solutions to most of these difficult problems. The conceptual framework of creating successive modes of organization at higher levels of complexity and order has significant practical implications in shaping the systems theory of organization. We will deal with this exciting conception in Chapter 7.

4.3.5. Recap

• Development of an organization is a purposeful transformation toward higher levels of integration and differentiation. It is a collective learning process by which a social system increases its ability and desire to serve itself, its members, and its environment.

• For every level of differentiation there exists a minimum level of integration below which the system would disintegrate into chaos. Conversely, higher levels of integration require higher degrees of differentiation to avoid sterility.

• Unless an organization effectively serves the purposes of its containing systems and its purposeful parts, they will not serve it well. This requires that the organization be designed to enable the parts to operate as independent systems with the ability to be relatively self-controlling while acting as responsible parts of a coherent whole that has the right to make collective choices.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.