Chapter nine. Business Architecture

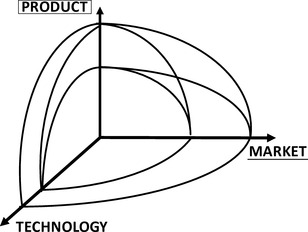

In a global market economy with ever-increasing levels of disturbance a viable business cannot be locked into a single form or function any more. Success comes from a self-renewing ability to spontaneously create structures and functions that fit the moment. Creation of the ability to continuously match the portfolio of internal competencies with the portfolio of emerging market opportunities is the foundation of an emerging concept of new business architecture. In general, business is usually defined in terms of three dimensions. A know-how, or technology, that is transformed into a set of tangible products or services and delivered via an access mechanism to its target customers or markets. Interactive business architecture consists of a set of distinct but interrelated platforms creating a multidimensional modular design that defines the nature of relationships among technology, product, and market. This business architecture eliminates periodic restructuring and shift from one dimension to another in search of an effective competitive base.

Keywords: Bureaucratization; Business environment; Capacity utilization; Core competency; Cost plus; Critical processes; Experience curve; Fee for service; Insatiable demand; Internal market economy; Latency; Learning and control; Miniaturization; Outsourcing; Paradigm in use; Performance criteria; Performance measure; Reliability of demand; Stakeholders expectation; Strategic intent; Synergy; Target costing; Third-party payer; Throughput; Variable budgeting; Viability matrix

In a global market economy with ever-increasing levels of disturbance, a viable business cannot be locked into a single form or function anymore. Success comes from a self-renewing capability to spontaneously create structures and functions that fit the moment. In this context proper functioning of self-reference would certainly prevent the vacillations and the random search for new product–markets that have destroyed so many businesses over the past years.

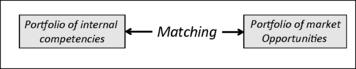

Creation of the ability to continuously match the portfolio of internal competencies with the portfolio of emerging market opportunities is the foundation of the emerging concept of new business architecture (Figure 9.1).

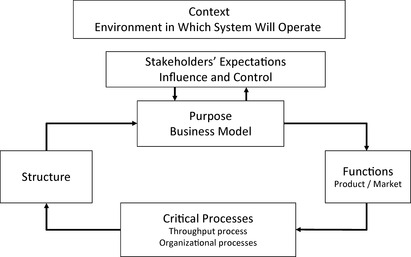

Business architecture is a general description of a system. It identifies its purpose, vital functions, active elements, and critical processes and defines the nature of the interaction among them. Business architecture consists of a set of distinct but interrelated platforms creating a multidimensional modular system. Each platform represents a dimension of the system signifying a unique mode of behavior with a predefined set of performance criteria and measures. Designing business architecture follows the general rules of interactive design described in Chapter 7. It therefore starts by assuming that the system to be redesigned has been destroyed overnight but that everything else in the environment remains unchanged. The designers have been given the opportunity to design the system from scratch.

Figure 9.2 outlines the process of designing business architecture.

9.1. The system's boundary and business environment

The first step in designing system architecture is to define the system's boundary and appreciate the environment in which it intends to operate.

To define a system's boundary we need to understand the behavior of its stakeholders. A stakeholder of an organization is any individual or group who is directly affected by what the organization does and therefore has a stake in its performance. Therefore, we need to know the following: Who are the major stakeholders? What are their expectations? What are the desired properties of the system from their perspective? What is their influence? Which critical variables do they control (or influence)? For example, in a market economy the customer provides the operating income, the boss defines the membership, stockholders pay the capital, suppliers are the source of complementary technologies, and distributors provide access to customers. However, stake and influence do not necessarily go hand in hand; a high stake is often coupled with low influence, and vice versa. For example, customers with the highest level of influence (refusing their patronage) show a very low level of stake in the system. On the other hand, employees with a very high stake in the system often have low level of influence. Shareholders with very high influence have the least at stake. If unhappy, they simply take their money out.

As we alluded to before, the system's boundary is a subjective construct defined by the interest and level of influence and/or authority of the participating actors. Therefore the system consists of all variables that could be sufficiently influenced or controlled by the participating actors. Meanwhile, the environment in which the system must remain viable consists of all those variables that, although affecting the system's behavior, could not be directly influenced or controlled by the participating designers.

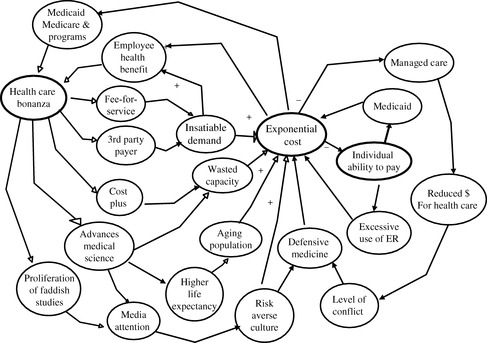

In this formulation the business environment must remain intact, so it is critical to get an appreciation of its behavior by understanding: How is the game evolving? What are the drivers for change? What are the bases for competition?Figure 9.3 captures the drama of the health-care system. The game is still evolving. The industry has yet to find alternatives for the three villains of third-party payer, cost plus reimbursement, and fee for service, which are assumed responsible for creating insatiable demand. Note how a counterintuitive event — General Motors' agreement with the labor union to cover the health-care costs of workers in exchange for a one-time concession on wages combined with President Johnson's Medicare and Medicaid programs — led to the “health-care bonanza” and a dynamic that no one has figure out how to deal with.

As for the change in the bases of competition, consider the fact that we are past the age of mass production based on the interchangeability of parts and labor. We have entered the mass customization era where success is defined by producing smaller batches of customized products at lower break-even points. In 1999 Honda's break-even point for a given model was two thousand cars, whereas Ford Motor Company needed five hundred thousand units of the same model car to break even. Economy of scale and mastery of a simple procedure was the cornerstone of mass production, but the multi-skilled knowledge worker is now the core requirement of mass customization. Globalization means that price is set in the global marketplace, therefore, it is considered an uncontrollable variable and the cost becomes the controllable variable (target costing). In the “cost plus economy” cost is considered uncontrollable and price is the controllable variable (target pricing). Efficiency in performing a routine used to be a virtue when the cost of automation outweighed the cost of labor. The digital revolution has reversed the equation. Increasingly cheaper computers have rendered the “narrow skill” and “simple procedure” approach obsolete. When it comes to performing a specific procedure the computer is the ideal actor. Knowledge workers of today are capable of putting together whatever pieces of know-how it takes to produce an integrated solution.

There was a time when problems could be neatly formulated and conveniently solved within the confines of a single discipline or department. Modern problems, however, are increasingly complex and interrelated. These problems are messy; they come in bundles and require a different approach. The knowledge workers of today are not only required to be competent in their own vocation, but they are supposed to be intimately aware of the total context and overall process within which they are to collaborate.

9.2. Purpose

Many common sense statements invoked in the process of developing organizations prove counterintuitive. The surprise element is not because people are knowingly disingenuous. Emerging consequences contradict expectations because the operating principles are rooted in assumptions that belong to different paradigms. Such surprises are inevitable unless the underlying premises are surfaced and their eventual consequences are mapped out.

The purpose of business enterprise is essentially defined by its implicit paradigm. If the organization in question operates in a mechanistic mode, then it is considered to be a tool of its owner. Its purpose therefore would be to serve the purpose of its owner. Performance criteria of a tool, of course, would be efficiency and reliability. Purpose of organization in a biological mode of operation is survival, thus its performance criterion would be growth at any cost. Profit as the means of growth finds additional social value and overcomes the negative stigma of the mechanistic era. Since organization in a sociocultural mode of operation is considered to be a voluntary association of purposeful members, its purpose would be to serve its members and its environment by doing more and more with less and less.

As stated so elegantly by Milton Friedman (1962), ultimately “business of a business is business”; therefore, for designers of business architecture understanding the vision of the desired future of the enterprise and its business model are of the utmost importance.

The initial sketches of the vision of the desired future usually can be put together after the first iteration of interactive design. Although we are told that visions are escape mechanisms of daydreamers, without a vision there will be no sense of direction. Without a vision all possibilities would have equal values; there would be no basis to judge the relevancy of the emerging opportunities.

The business model, on the other hand, defines the way a business generates value, creates a deliverable package, and exchanges it with money. Today amazing originality is shown when developing new business models, which is radically influencing the traditional business concepts. Consider, for example, the case of the search engine Google. By providing free service to a group of consumers it can make so much money from advertisers that it exceeds the value of the giants listed in the Dow Jones index. Creating a multi-billion-dollar business to create, package, and sell operating systems independently from computer hardware, as is done by Microsoft, was inconceivable for those of us who worked for IBM during the 1960s. In the early 1990s, I was involved with a Fortune 100 company as a consultant in the acquisition of a $10 billion business. The total sum of money that all service providers — legal, financial, and management — charged the client was less than $500,000. This fee was based on actual time spent multiplied by the hourly rate. Today the same task would cost over $200 million based on a business model that works on percentage.

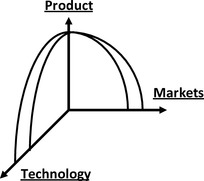

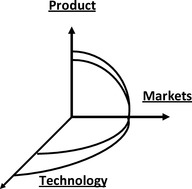

In general, business is usually defined in terms of three dimensions: a know-how or technology, which is transformed into a set of tangible products or services and delivered via an access mechanism to its target customers or markets. Business architecture defines the nature of relationships among the three dimensions of technology, product, and market.

Traditionally one of these dimensions has been designated as primary, forcing the other two into subordinating roles.

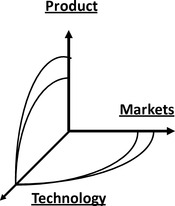

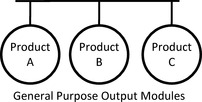

When the product defines the business, technological requirements and the markets to be served are determined by product characteristics. Alternative technologies are sought for making the product, and different markets are sought for selling the product (Figure 9.4).

The success of a product-based business is usually measured by the success of its product divisions, which is why everything is easily compromised and subordinated to the product. However, when the potential value of a given technology somehow exceeds the value of the product it supports, the business faces a dilemma.

Unfortunately, experience shows that, in these cases, technology is always compromised. In a product-based business, the product managers are the bosses. They see technology only as a competitive advantage for their product; therefore, technology will never get the chance to realize its potential in the context of a product-based business. Quite a few cases support this assertion, but the most conspicuous is the fate of the first Apple operating system (the famous graphic interface). This phenomenal operating system was used exclusively to sell Apple computers when its potential had been much higher than the maximum potential of the initial Apple products it supported at the time. This was proven by Microsoft, whose claim to fame, Windows 95, was an imitation of the initial Apple operating system used by all computer producers. It was reported that IBM spent billions to lay off about 200,000 people — some say the best available knowledge workers. But it did not consider capitalizing on its advanced “digital technology” and state-of-the-art “C4 technology” to become the major player in the most potentially explosive market of the time — “electronics packaging.”

When the market is used as the basis for defining the business, the characteristics of the market determine the product mix and the type of skills and technologies required to produce it (Figure 9.5). Procter and Gamble, for example, provides as many of the products sold in supermarkets as it can profitably make.

However, the trauma of the defense industry, when its market collapsed overnight, was another confirmation that the price tag on selecting a single pattern of existence is very high. The industry's inability to take advantage of its access and knowledge of emerging Internet technology was not surprising. Managing technology requires a different set of criteria than those necessary to manage products and/or markets.

Finally, when the business is technologically defined, a variety of products are developed around a given core technology, using the same base of know-how, and sold in different markets (Figure 9.6). For example, 3M defines itself as being in the “sticking” business. The company revolves around technologies used to bind different things together (from Scotch® tapes and composite structures to electronics packaging).

Using its materials science and processing technology, it continually searches for new products that it can produce and offer in different markets. Managing a technology-based business not only needs broader planning vision, but also the ability to use the same knowledge in different contexts.

The success or failure of each approach depends on its compatibility with the emerging competitive challenge at the time. Because competitive games change over time, they force companies to switch their strategic emphasis from one dimension to another. Since each strategy has organizational implications in terms of authority and responsibility, changes in strategy require changes in the organizational structure and the dominant culture of the business. As competition intensifies and the changes become more frequent, this unidimensional approach becomes more ineffective. Shifts from one dimension to another in search of the effective competitive base cause organizational turmoil and strategic confusion. The waste and frustration associated with periodic restructuring have necessitated a search for alternative solutions.

Interactive systems architecture uses product, market, and technology in an interactive mode. It recognizes the necessity for achieving competitive advantage in all three dimensions of market, product, and technology (Figure 9.7).

The objective is to capitalize on the totality of the value chain and actively generate synergy among the three dimensions. An interactive architecture is based on managing the interactions among technology, product, and markets.

The emerging multidimensional modular structure, with a different business model and reward system for each dimension, dissolves the need for subordination or suboptimization around any one business dimension, eliminates periodic restructuring, and shifts from one dimension to another in search of an effective competitive base.

In an unpredictable, turbulent environment, the viability of any design depends on its capability to explore and exploit emerging opportunities all along the value chain. These opportunities, which emerge out of interactions among technology, product, and markets, remain inaccessible to unidimensional cultures and architecture. A platform that identifies the basic dimensions of the multicultural architecture is the starting point from which the initial elements of the value chain will evolve. As the business gains maturity and stability, new elements will be added.

In formulating the strategic intent of an enterprise we must remember that competitive advantage is a dynamic and relative phenomenon; it is different in different contexts and in reference to different classes of users. For example, the element of time, as a basis for competition, is not the same for supermarket shoppers at 10 a.m. and those at 5 p.m. Often the former are spending time, whereas the latter are interested in saving time. What might be an advantage in one context could be a disadvantage in another. This explains the success of convenience stores despite their higher prices.

Now recall the concept of the experience curve, which is volume-based learning. An important outcome of learning through an experience curve is process control. The volume-based control system is usually achieved in a given context after using considerable time and resources. When this context is changed or even modified, the whole knowledge that was gained in controlling the particular process is lost. Now assume that, somehow, we have developed the ability to make this know-how transferable to different contexts and applications without having to go through the time- and resource-consuming notion of the experience curve each time. If we can really do this, then we have created a core competency, or an unmatched opportunity for competitive advantage. Formulating and developing state-of-the-art knowledge that can be operationalized in different contexts such as process technology, is, in my opinion, a much more profound way of formulating a competitive strategy. For example, adding digital technology to miniaturization, as new core competency, has provided Sony with a whole new dimension in its competitive strategy.

Strategic intent can be formulated as a core competency. In this context a core competency is the attribute of the organization as a whole; it cannot be housed in a single division. Creation of the ability to transfer knowledge to different contexts requires multiple sources of learning and application.

9.3. Functions

To serve its own interest in an exchange, a purposeful system ought to have something to give back to its environment. Therefore, it needs access to a group of potential users with purchasing power who have a need or desire for the product or service it can produce. A true customer, in reality, is a pain in the neck. He/she has something you want, and his/her satisfaction, in competition with other sources of supply, is the price you have to pay to get it.

Selecting a product-market niche is the first step in defining an enterprise's function and designing its architecture. We need to answer the following questions: Whose problem are we trying to solve? What solutions are we offering? How will we access the target customers? And, finally, will the target customers have sufficient purchasing power to pay for this solution?

Competitive advantage is an attribute of outputs produced by an enterprise. It is a difference that makes a difference, for a given class of users, in affecting their choice. And it must be transferable to a value for the provider.

To select a desired product-market niche, it is necessary to differentiate the customer base. There are many different ways to segment a market. Each segment reveals something new about the nature of the market and the behavior of the target customers. Use as many criteria as you can to differentiate user characteristics and identify their purchasing habits. The most useful segmentation is the one that identifies:

1. The group of customers for whom the desired properties of the product are more compatible with the organization's potential capabilities

2. Those potential customers who have less stake in the old product system and therefore display less inertia and offer easier access

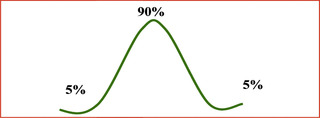

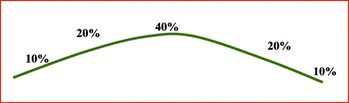

Using the traditional bell-shaped distribution curve to differentiate the customer base assumes that the majority in the big category alone defines the market (Figure 9.8). The behavior of this single group, considered normal, is used to determine the desired properties of outputs, while behavior of the smaller groups, considered nerds, are conveniently ignored as insignificant.

Struggle for a share of this monolithic market leads to a game of intense competition between big powerful players. However, increasingly it seems that the nerds are taking over, and the bell-shaped curve is somehow flattening out (Figure 9.9). Targeting and understanding behaviors of the smaller groups that are emerging rapidly provides the best, and sometimes only, window of opportunity for a new player to successfully enter the game and skillfully avoid the intense competition at the early stages of the entry to a new market.

9.4. Structure

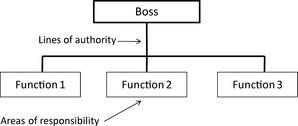

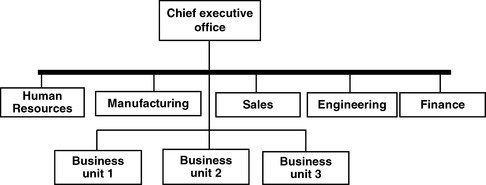

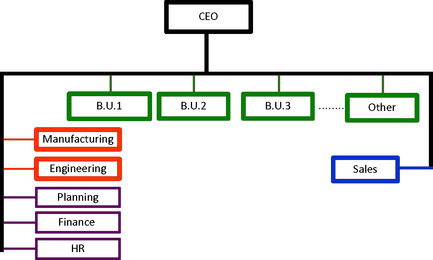

Traditionally, organizational theory deals with two types of relationships: (1) responsibility (who is responsible for what) and (2) authority (who reports to whom).

Structure, so conceived, can be represented by a two-dimensional chart in which boxes represent responsibilities and levels and lines represent the loci and flow of authority (Figure 9.10).

The criteria used for dividing the whole into areas of responsibility, and for determining their relative importance (line of authority), represent the major differences among organization theories. These criteria, not surprisingly, have evolved primarily around three components of a system: input (technology), output (products), and environment (markets).

Depending on the nature of the competitive game at any given time, a priorities scheme is used to designate one component as primary and the other two as subordinates. For example, when the ability to produce was the defining factor of competition, input became the primary concern rendering market and product subordinate to manufacturing. The marketing era saw the shift of emphasis from production to market and thus subordination of manufacturing to marketing. It seems that a self-imposed unidimensional concept of organization has prevented the realization of a multidimensional alternative.

For a majority of designers, the unidimensional mode of organization based on structurally defined tasks, segmentation, and hierarchical coordination of functions seems the only acceptable way of organizing work. A predominant management culture continues to value command and control very dearly and considers any form of variety in the organizational structure unacceptable, wasteful, and at best impractical.

As discussed earlier in this chapter, the multidimensional structure assumes that the three common criteria — input (technology), output (products), and environment (markets) — are complements. Treating them as interdependent dimensions and managing their interactions eliminates the need for periodic reorganization when a change in the competitive environment necessitates a change of emphasis from one orientation to another, for example, from products to markets, or vice versa.

The viability of any organization depends on its ability to adapt actively to the changing requirements of the emerging competitive game. The ability to adapt requires some form of flexibility and responsiveness, which in turn demands that some degree of redundancy be built into the system.

A modular structure embedded in a multidimensional scheme can achieve the required level of flexibility to create an adaptive, learning system by shifting its attention from micro-managing the parts (power-over) to macro-managing the interactions (power-to-do).

Power-to-do is what organization is all about. It should not be confused with power-over. Power-to-do is the foundation of organizational potency and duplication of power, whereas power-over is about domination. Potent organizations are not built on impotent principles. Power-to-do multiplies when it is duplicated in special purpose modules. These modules enjoy considerable freedom as long as they meet the interface and functional requirements of the larger system of which they are a part. In any system it is differentiation that keeps the system alive and potent. Organizations that differentiate and integrate create real value for themselves and others.

Multidimensional, modular design, in my experience, is the most practical means of handling complexity and uncertainty. It makes it feasible to implement a complex design without getting lost in the process.

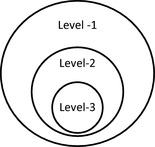

Multidimensional modular structure consists of a set of distinct, but interrelated, platforms. Each platform represents a dimension of the system signifying a unique context, mode of operation, and predefined set of performance criteria and measures. Each platform hosts a set of special purpose modules with the same set of behavioral characteristics. Relationships and the interfaces among platforms are explicitly defined, integrating them into a concept of the whole. Parts operate as independent systems with the ability to be relatively self-controlling and act as responsible members of a coherent whole with the ability to respond effectively to the requirements of the containing system.

For example, a technology platform provides a friendly environment for component builders. Component builders are modules that usually host a core technology and therefore require a different mode of management and performance criteria and measures than those necessary for managing and controlling the marketing modules.

The organization, so conceived, then becomes capable of expanding or contracting by the addition or deletion of replaceable modules that have the means of vertical and horizontal interactions. The resulting mode of organization is capable of redesigning its structure and redefining its functions, allowing it to exhibit different behavior and produce different outcomes in the same or different environments. This means work can be organized in a variety of ways, and indeed, an organizational choice does exist. Figure 9.11 is an outline of the multidimensional modular design.

9.4.1. Output Dimension

Responsibility for achieving an organization's end is vested in the output dimension. The output dimension or platform consists of a series of general purpose, semi-autonomous, and ideally self-sufficient units charged with all the activities ultimately responsible for achieving an organization's mission and production of its outputs. Note that the semi-autonomous, self-sufficient, and purposeful units, for simplicity, are referred to as modules. Modules are self-sufficient and autonomous to the degree that the integrity of the whole system is not compromised.

Each output module represents a specific level in the hierarchy of multilevel purposeful systems (Figure 9.12). It is a miniature of the whole — the larger system of which it is a part.

Since each module may consume scarce resources from its environment, its outputs should be responsive to the needs of the environment. The lowest level output module is the smallest unit that can be accountable for producing a tangible, measurable output.

Performance of an output module preferably should be as independent to the behavior of other peer output modules as possible; it should have enough authority over its resources — money and people — to be responsible and accountable for its success or failure. It should also be able to retain a percentage of its contributions above a minimum level for incentive and internal development.

Each output module is responsible for making those decisions that affect only its operations. Decisions that impact the other units will be made at higher levels with the participation of all affected modules.

An output module is usually conceived as a unit hosting a product, a project, or a program. An effective product module has an entrepreneurial role. It is responsible for the development, design, marketing, and profitability of the final product. Although they should not be burdened by responsibilities for fixed production facilities, output managers should have the financial authority to select the production facilities and distribution systems (Figure 9.13).

Placing a high-capital-intensive production facility in a product module will tie the fates of an organization to a single product. The facility-oriented division or module unwilling to develop any product that would require use of different facilities would experience the cycle of growth, maturity, and inevitable decline just as the product does.

Ideally, the output platform would be a virtual entity and would have up-to-date information about environmental opportunities and internal competencies. It would have the distinct capability to consider a new set of alternatives and choices that might be available to the organization. Finally, modules of the output platform should have the ability and the authority to re-engage inputs in a new order.

9.4.2. Input Dimension

To create a system that is more than the sum of its parts, the organization needs to fully use its synergy. Economies of scale, the need for specialization, technological imperative, and development of core technologies are among the reasons why some functions and technologies required by output modules ought to be shared.

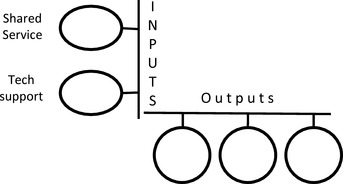

These shared services and specialized functions can be provided by groups of special-purpose modules, which together constitute the input dimension of the organization (Figure 9.14).

For example, designating the manufacturing unit as a profit center in the input dimension not only results in a more competitive and flexible facility management, but it also provides the product managers with the freedom to buy their manufacturing requirements from within or outside the organization without constraint from fixed facilities.

Input modules, in general, are provided with working capital and are expected to earn their operating expenses plus a return on the investment by charging the market price for their services.

If insufficiency or unpredictability of demand makes it necessary to provide additional support for an input function, then the general rule is to subsidize the demand instead of the supply. In the early stages of the conversion, the operating budget of an input unit may be given to it by means of a purchase contract for its total services.

However, in general, centralization should be avoided unless one or all of the following situations weigh overwhelmingly against decentralization of a particular service.

9.4.2.1. Uniformity

Some aspects of the system will be centralized when they are common to all or some parts and cannot be decentralized without rendering serious damage to the system's proper functioning. For example, in areas such as measurement systems, where common language and coordination are major concerns, uniformity will serve as a criterion for centralization. Meanwhile, certain activities that, because of their nature, are deemed indivisible and thus require a holistic design can also be centralized. For example, the effectiveness of a comprehensive information system lies in its holism, consistency, real-time access, and proper networking to transfer information as needed to different users. Developing such a system requires cooperation and coordination among all actors in the system.

9.4.2.2. Economy of scale

Although economy of scale is generally considered an important factor in creating shared service, the trade-off between centralization and decentralization of each function should be made explicit to prove that the benefits significantly outweigh the disadvantages before the function is moved to shared services. In this case, it is expected that a service, once centralized, will either generate significant savings for the system as a whole or help those units that otherwise would be unable to afford it on their own.

9.4.2.3. Core technologies

Feeling that a certain level of mastery in a given technology will be critical for the enterprise's future success, management may decide to centralize, develop, and make the technology available for all units. Sometimes a technology developed by an output unit has a much greater potential in the marketplace than as a competitive advantage to the product division. In this case it is management's responsibility to identify it as a core technology and centralize it for full-scale development.

Whatever the justification for centralization, the input units will have to become state-of-the-art and cost-effective providers of choice. However, a sure way to obstruct the functioning of an input unit is to mix its function with that of control. This practice undermines both the effectiveness of the service function and the legitimacy of the controls.

To protect themselves against the creeping hegemony of service providers and the obvious risks involved in relying on control-driven services, output units resort to duplicating the support services that could otherwise be easily shared and effectively used. Rampant, excessive duplications of services are symptomatic of the natural reaction of operating units to service functions assuming the additional function of control. On the other hand, disguising a legitimate and necessary control function as a service function transforms the nature of control from learning to a defensive and apologetic act.

Extra care should be taken to ensure that none of the functions of shared services undergo a character change and assume control properties. Under the pretext of a need for consistency and uniformity, there is a natural tendency to let the service provider perform the necessary monitoring and auditing function. This practice has always proved misguided. The providers cannot avoid the slippery slope of wanting, increasingly, to assume a control function. This obviously would scare away users who did not expect to find a new boss in the guise of a server.

Whereas shared services will provide the customers with requested services (such as information, benefits, payroll, and billing), it will be the planning and control system that will be setting the policies and the criteria governing these services as well as conducting the necessary monitoring and enforcing functions to ensure proper implementation of those policies.

9.4.3. Market Dimension

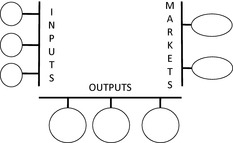

Market, the third dimension of the organization, is defined as the access mechanism to a class of customers having sufficient purchasing power and an explicitly known need or desire for a given service or product (Figure 9.15).

The market dimension is the interface with the customers. In most cases, this is where organization actually happens. Depending on the diversity of the customer base, there might be a need to create a number of costly distribution channels. It then becomes imperative to share these channels with other output units.

Two major functions of the market dimension are distribution and advocacy. Distribution represents the organization to the outside. Advocacy is responsible for sensing environmental conditions and exploring the expectations of the customers. Advocacy serves all those affected by the activities of the organization. Especially important is its role in advocating the consumer's point of view inside the organization.

Distribution and advocacy units may be organized geographically or by market segmentation. However, if one is organized geographically, the other should be based on market segmentation.

Input, output, and market platforms form an interactive whole engaged in an ongoing process of redesign to create new orders spontaneously as deemed necessary.

Because interactions among purposeful actors take many forms (actors may cooperate on one pair of tendencies, compete over others, and be in conflict over a different set, all at the same time), we are dealing with a dynamic structure. In addition members learn, mature, and change over time. The result is an interactive network of varying members with multiple relationships, re-creating itself continuously.

9.4.4. Internal Market Economy

Defining the relationships between input, output, and marketing modules is the most critical task of this conception. Extreme difficulties are encountered when several output units share the vital services of an input or a market unit setup as an overhead center.

The key problem of matrix organizations also has been management of the implicit, ambiguous, and conflicting relationships between the network of input and output units. The “two-boss system” not only has failed to understand the problem, but also has resulted in confusion and frustration.

The answer for this inherent complexity is to create an internal-market environment, 1 which converts the relationships between input, output, and market units into the same types of relationships that exist between a supplier, a producer, and a distributor.

1The idea of an internal market was first advanced by Forrester (1965) and Ackoff (1981). For a detailed treatment see Halal, Geranmayeh, and Pourdehnad (1993).

While superior–subordinate relationships have traditionally been the only building block for exercising organizational authority, the supplier–customer relationship introduces a new source of influence into the organizational equation. With the supplier–customer relationship emerging only in an internal market environment, the helpless recipient becomes a real customer. Armed with purchasing power, the customer becomes an empowered actor with the ability to influence and interact with his/her supplier in such a way that both parties together can now define the type, cost, time, and quality of the services rendered.

Creation of the internal-market mechanism, and thus a supplier–customer relationship, is contingent upon transforming the shared services into a performance center. Unlike overhead centers, performance centers do not receive a fixed budget allocated from the top; they have working capital with a variable operating budget. In this model, expenses are proportional to the income generated by the level of services rendered and the revenues received in their exchange. Treating all units as performance centers makes it possible to evaluate every unit at every level in exactly the same way.

These two pairs of horizontal (supplier–customer) and vertical (superior–subordinate) relationships are complementary and reinforce one another. While superior–subordinate defines the formal authority dealing with hiring, firing, and promotion, the supplier–customer relationship creates a new source of influence that tries to rationalize demand.

In the absence of an internal-market environment, there is no built-in mechanism to rationalize demand. An agreeable service provider with a third-party payer creates and fuels an insatiable demand. A disagreeable service provider, on the other hand, triggers prolific duplications of the same services by the potential users. This results in an explosion of overhead expenses in the context of an essentially cost plus operation. The trend is irrational, and the corrective interventions prove to be ad hoc and ineffective at best.

Creating an internal market not only eliminates the growing problems of bureaucratization, but it also provides an effective means for dealing with allocation and evaluation problems. Meanwhile, it gives an organization a market orientation by forcing each part to consider the marketing consequences of its actions.

In the internal-market environment, modules ought to have a choice of selling or buying their required services from inside or outside the organization; otherwise, internal buyers or sellers will have a monopolistic advantage. Higher level authority can always override outsourcing by agreeing to pay the cost incurred or the profit lost.

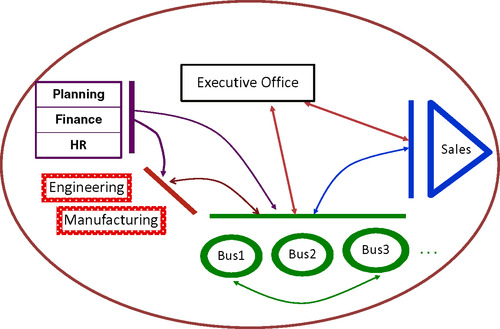

The following section provides a real-life example of converting traditional organization to multidimensional design. During a design session, a group of executives produced the following organizational chart as the initial structure of their business (Figure 9.16).

When I asked the executives whether or not they would mind if I changed their design into the following format (Figure 9.17), they had no objection: “If you like colors [patterns] use as many as you like,” one of them said jokingly.

However, despite the apparent similarities in the two designs, significant differences existed between them.

Figure 9.16 represents a design concept concerned only with defining responsibilities and the line of authority. The case at hand is a mix of functional and divisional units all reporting to the CEO. The relationships among peer groups are conveniently ignored as though the organization is an aggregate of unrelated parts all only related to a CEO. This is a linear conception of structure in which a single pair of a superior–subordinate relationship is used as the building block of the organization. But to produce the structure that fits our purpose here — that is, to design a business architecture — parts not only have to be differentiated and their roles clearly defined, but the relationships among all peer units must be explicitly known and understood.

This is why version two used color to differentiate the parts and group them according to the roles they would play in the organization. In this context, a part can assume the function of input, output, market access, or control. In this particular case, green was used to identify the output units (product–market divisions), yellow was chosen to identify the input (manufacturing and engineering), red was used for control (finance and human resources), and blue for market access (sales units).

To demonstrate the flow and the relationship in the value chain, the following format was adopted to underline three basic relationships among peer units (Figure 9.18):

1. Output units are in such intense competition with one another that animosity among sister organizations is much higher than it is with outside competitors. To avoid structural conflict, output units should operate virtually independently of one another with a modular structure and adequate levels of autonomy and self-sufficiency.

2. Relationships between each output unit with the input and market access units are complementary. It is the same relationship that exists between a producer and its suppliers or between a producer and its distributors. An effective interface with all-out cooperation between them is a must to generate a competitive throughput. If the output unit is to be held accountable for the ultimate outcome and proper integration of the operation, it must have some kind of leverage on both input and market access units to influence their behavior.

3. The relationships between control units and all the input, output, and market access units are one way, usually bureaucratic, and more or less autocratic in nature. This is why combining a service function with a control function in a single unit, which is usually done under the pretext of coordination, is a design for failure. For example, when any one of the service functions like Human Resources, Legal, or even Information Services becomes provider and controller at the same time, both the control and service functions will be undermined.

Finally, the linear framework of version one lends itself to a unidimensional concept of system architecture where product, market, and technology are arranged in sequential order based on their relative importance. The criteria used for determining the order of subordination define the major differences between alternative designs. The second version tries to create an interactive relationship among technology (input), product (output), and market (access). This requires a multidimensional structure.

To create a multidimensional structure we need at least two distinct types of relationships. A single superior–subordinate pair can produce only a unidimensional structure; despite claims to the contrary, a matrix organization is not a multidimensional design. Two-boss systems fail because they create confusion in the power system. Using the superior–subordinate pair in two contexts creates frustration, not interaction.

For interaction among peer units, an interactive paradigm uses two distinct pairs of relationships: (1) superior–subordinate and (2) customer–provider. This becomes real and meaningful when, and only when, the user of the service has the power of the money and controls the payment to the provider. This requires that providers function with a variable budget paid by the customer in exchange for their services. If a provider of a service has a fixed budget, which is directly paid by the boss, then the boss becomes the customer as well. In this case the user of the service has no power and the customer–provider relationship is meaningless.

Customer–provider relationships can be forged between input, output, and marketing units in the context of an internal market mechanism. If properly operationalized, the customer–provider relationship will effectively supplement the superior–subordinate pair and provide the organization with a much desired market orientation. This means each part of the organization understands and lives with the marketing consequences of its actions.

The unit of organization, in this context, is a performance center, a value-adding link in a well-defined value chain. Although each unit has only a single boss (the superior–subordinate relationship with its containing system), it can have several customers and suppliers. Customers are the sole source of its operating income.

The measure of each unit's performance includes not only its own operations but also the contribution it makes to the success of its internal suppliers. All units have working capital and operate on a variable budget dependent on the throughput of the system.

9.5. Processes

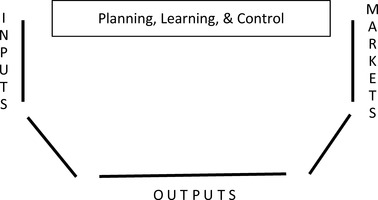

The essential characteristics of a throughput and organizational processes were discussed in Chapters 5 and 6. Recall that throughput processes are those directly concerned with the actual output of the organization. Organizational processes, on the other hand, are concerned with creating integration, alignment, and synergy among the organization's parts. In this context, the planning, learning, and control system is an integral part of designing architecture.

9.5.1. Planning, Learning, and Control System

An organization's decision-making process is reflected in its mode of planning, learning, and control system. Planning, as traditionally practiced, is either one or a combination of two dominant types: reactive and proactive. Reactive planning is concerned with identifying deficiencies and designing projects and strategies to remove or suppress them. It deals with parts of an organization independently of each other.

An organization is a system whose major deficiencies arise from the way its parts interact, not from the actions of its parts taken separately. Therefore, it is possible, and even likely, that improving the performance of each part of an organization separately will bring down the organization's performance as a whole.

Proactive planning consists of two major activities: prediction and preparation. The objective is to forecast the future and then prepare the organization as well as possible. Unfortunately, such forecasts are chronically in error, since the social, economic, and political conditions, as well as the behavior of supplier, consumer, and competitor, are affected by what the planned-for organization and others like it will do. Therefore, it is precisely such plans taken together that shape the future.

Systems methodology rests on the interactive type of planning, which assumes that the future is created by what others and we do between now and then. Therefore, the objective is to design a desirable future (next generation of the system) and to invent or select ways of bringing it about (realization).

The planning, learning, and control system is the executive function of the organization. It oversees the operation of the whole system by managing the interaction between the dimensions. The executive function is also responsible for creating a vision, generating a shared image of a desired future, and providing the leadership for achieving the organizational mission. It has final responsibility for financial viability, technological ability, and human effectiveness of the organization as a whole.

Our design must be viable in the existing environment. To assess the viability of a business enterprise requires a measurement system. Defining the characteristics of the measurement system is the last connecting piece in the design of architecture.

9.5.2. Measurement System

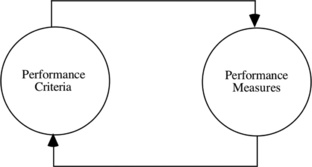

To develop an effective measurement system we need to deal iteratively with two elements: performance criteria and performance measures (Figure 9.19).

9.5.2.1. Performance criteria

Performance criteria are the expression of what is to be measured and why (i.e., how success is defined). The selection process involves identifying dimensions and/or variables relevant to an enterprise's successful operation.

Relevancy is the most important concern in selecting performance variables. Traditionally, the overriding concern has been with the accuracy of measures. Because we find it difficult to accurately measure what we want, we have chosen to want what we can accurately measure. Unfortunately, the more accurate the measure of the wrong criteria, the faster the road to disaster. We are much better off with an approximation of relevant variables than with precise measurement of the wrong ones.

Viability of a business enterprise is an emergent property. It is the product of the interactions of various entities. It cannot be measured directly (i.e., by using any of the five senses). We can only measure its manifestation. Growth is the most popular one, but some prefer return on investment while others like net present value of future cash flows. Unfortunately, using the single manifestation of a phenomenon as the measure of an emergent property has proved misleading and very costly. For example, if a business is successful, chances are it will grow; however, growth alone does not mean that the business is successful. The same outcome (manifestation) could be produced by different means. Lousy acquisitions can produce high rates of growth but at the same time destroy the company.

Therefore, when we measure an emergent property by means of its manifestation we have to do it along several dimensions. For example, concern for people, when combined with the concern for production, has quite a different manifestation from the one without it. In his famous work, The Managerial Grid, Blake (1968) demonstrated how the nature of a variable in a “1.9 orientation” is different from the nature of the same variable in a “9.9 orientation.” Freedom without justice leads to chaos, while justice without freedom leads to tyranny.

9.5.2.2. Performance measures

Performance measures are the operational definition of each variable, that is, how each variable is to be measured specifically. For example, if we have identified capacity utilization as performance criteria, then turnover ratio might be designated as its measure. Now we would need a procedure for calculating turnover ratio (e.g., divide sales by assets, divide revenues by assets, or divide output by input).

An important consideration in selecting any measure is its simplicity. The cost of producing a measurement should not exceed the value of the information it generates. Although objective measures are preferable, if the cost of obtaining an objective measure is prohibitive, then use a subjective one. Remember that collective subjectivity is objectivity (provided that collectivity represents a variety of value systems). For example, in evaluating the performance of a gymnast we rely on the collective judgment of a number of different judges.

Development of effective performance measures is easier said than done. More often than not the operational definitions are left vague and ambiguous, even when the underlying concepts are relatively simple, such as minimizing the cost. The usual practice of allocating overhead to various operating units demonstrates how an innocent matter of a convenience produces unintended consequences.

The criteria for allocation of overhead are usually based on conventional wisdom. Factors such as space occupied by a unit, or the labor content of a production process, are among the most popular ones. Since overhead usually constitutes more than 40% of the total cost, then we should not be surprised to see that these variables (space and direct labor) are the ones targeted for cost reductions. The fact that allocation rules were only a convention does not matter anymore. Once the allocation criteria become a rule, their relation with generation of cost, by default, is assumed to be causal, as demonstrated by the following case.

A large supermarket chain decided to close down ten of its stores because the accounting system showed they were not covering their allocated overheads. Since the shutdown had no effect in reducing overhead, the remaining stores now had to carry a larger share of the overhead. This in turn put a few more of the stores in the red, and they too were subsequently closed. The company was gradually withdrawing from the market. Then a new design was developed. Each store became responsible for its own operation without having to worry about any artificial overhead allocated to it. The surplus generated by each store was then passed on to the corporation as the income of the executive office. This made the executive office a profit center responsible for managing its operation, or so-called overhead, within the bounds of its income and the profit it needed to generate to meet the cost of its capital.

This situation is by no means atypical. With the prevalence of allocation rules based on labor, pressure is unduly shifted to direct labor. The default reaction is to lay off productive manpower. If the police department is facing deficits, policemen are the first to be fired. If schools are in financial trouble, the number of teachers is reduced. Reduction of operating units does not automatically reduce overhead, as management seems to assume. On the contrary, it will increase the burden of the remaining units until the whole system comes to a halt. In the mid-1970s, when per capita income was the conventional measure of development, sudden increases in oil prices produced instantly developed nations. Since this was not acceptable, a new set of indicators had to be developed. We now have a whole series of indicators that substitute for development, such as per capita steel production, per capita consumption of fuel, and so forth. It is not surprising, then, to find national development policies aimed at improving these measures, usually at an incredible cost to the society at large. Yes, winning is fun. But to win, one has to keep score. And the way one keeps score defines the game.

9.5.2.3. Viability matrix

The viability matrix developed in Table 9.1 is a framework for identifying the relevant dimensions — the performance variables — for measuring a business's viability or the different aspects of an operation.

The first dimension of this matrix identifies the variables that define the organization as a whole:

• Structure (inputs)

• Function (outputs)

• Environment (markets)

• Process (technology)

The second dimension of the viability matrix identifies the processes that define the totality of the management system:

• Throughput (production of the outputs)

• Synergy (management of interactions, adding value)

• Latency (defining problems and designing solutions)

The following definitions clarify some of the variables I have used in developing the scheme in Table 9.1.

Capacity utilization: Turnover ratio is a good indicator of capacity utilization. Compared to industry standards and best in class, it can signal the existence of an excess capacity that can be the major source of malfunctioning and fluctuation in the system.

Profitability: A dynamic and interrelated model of operating income, operating expense, investment (hard and soft), cash flow, and cost of capital.

Attributes of the outputs: The outputs are defined in terms of a quantifiable delivery of goods or services in time and space. They are measured on three dimensions: price, quality, and availability (time).

Reliability of demand: Demand for a product is reliable if the amount to be purchased can be predicted reasonably, and if actors beyond a firm's influence do not create unexpected fluctuations.

Throughput capability: The level of integration and effectiveness of activities required for the delivery of goods and services to satisfied customers is measured by cycle time, waste reduction, safety, and competency of critical processes.

Default value of the culture: The degree to which members accept responsibility and act with authority such as duplication of power, assumptions regarding the source of value, nature of competition, and relationship between equality and competence.

Credibility in the marketplace: A firm is credible when it can take actions its stakeholders will initially accept on good faith alone, that is, relationships with customers. This is the reflection of the firm and its sound relationships with customers, suppliers, and creditors.

Value-chain transaction index: This is a model for explicitly measuring the total contributions that a business unit makes to the profitability of the whole organization. It recognizes not only the unit's own profitability, but also its contribution to the profitability and/or success of other units within the context of a value-chain architecture.

Value-added ratio: A calculation of the value a unit produces in comparison to the value it consumes. The value a unit consumes is adjusted to reflect the cost of the resources, the amount and kind of inputs (scarce or excess resources) the unit consumes, and whether they are obtained internally or externally. The value a unit produces is also modified to recognize the contribution of each line in its product–market mix. For example, to encourage new product–new market introductions, one might multiply revenues generated by selling a new product in a new market by 120%.

Reward system: A priority scheme superimposed on the measurement system, which will allow the organization to assign priorities to particular variables (activities) and thus influence the behavior of the actors toward achieving organizational goals.

Product potency: Defines the degree to which the product meets a variety of customer needs and desires in absolute terms as well as relative to competitors' and substitute products.

Market potential: A market has potential when there is a real and sustainable need and sufficient (size) or growing purchasing power to satisfy those needs.

Intensity of competition: Competition is intense when the supply of a product is greater than the demand, and it is easy to enter but difficult to exit the market.

9.5.3. Recap

• Interactive design is a process for operationalizing the most exciting vision of the future that the designers are capable of producing. It is the design of the next generation of their system to replace the existing order.

• Design of a throughput process is essentially technology driven, whereas design of organizational processes depends on the paradigm in use.

• Winning is fun, but to win, one has to keep score. And the way one keeps score defines the game.

• The realization effort is not a one-time proposition. Successive approximations of the next generation design make up the evolutionary process by which the transformation effort is conducted.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.