Chapter five. Holistic Thinking

The distinction of systems thinking is its focus on the whole. But in most cases, this claim has been a simple declaration of intent without an explicit, workable methodology. What is systems methodology and how can we use it to get a handle on the whole? Three well-known inquiring systems (analytical thinking, synthetic thinking, and dynamic thinking) despite their success, are each only concerned with one aspect of the whole. Yet structure, function, and process represent three aspects of the same thing and with the containing environment form an interdependent set of mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive variables. Together this set defines the whole or makes the understanding of the whole possible. However, a set of interdependent variables forms a circular relationship. Each variable coproduces the others and in turn is coproduced by the others. Which one comes first is irrelevant because none can exist without the others. They have to happen all at the same time. Therefore, to handle them holistically requires understanding each variable in relation to the others in the set at the same time. This demands an iterative inquiry.

Keywords: Abdication of power; Circular organization; Circular relationship; Coalition; Competition; Conflict; Cooperation; Coproducer; Decision criteria; Duplication of power; Generation and distribution of power, knowledge, wealth, beauty, values; Iterative inquiry; Learning to be; Learning to do; Learning to learn; Membership; Power-over; Power-to-do; Systems approach; Systems dimension

5.1. Iterative process of inquiry

The distinction of systems thinking is its focus on the whole. But in most cases, this claim has been a simple declaration of intent without an explicit, workable methodology. What is systems methodology and how can we use it to get a handle on the whole? There seems to be more agreement on the desirability of systems thinking than on its operational definition.

Contrary to a widely held belief, the popular notion of a multidisciplinary approach is not a systems approach. The ability to synthesize separate findings into a coherent whole is far more critical than the ability to generate information from different perspectives. Without a well-defined synthesizing method, however, the process of discovery using a multidisciplinary approach would be an experience as frustrating as that of the blind men trying to identify an elephant. Positioned at a different part of the elephant, each of the blind men reported his findings from his respective position. “It's a snake.” “It's a pillar.” “It's a fan.” “It's a spear!” Consider the futility of trying to make sense of the whole by using this story without the prior conception of “elephant.” I am sure you experienced no frustration in sorting out the distorted information and putting it in perspective because the storyteller had already told us that the subject is an elephant. It seems we need a preconceived notion of the whole before we can glean order out of chaos.

A different version of the same story, found in Persian literature and narrated by Molana Jalaledin Molavi (Rumi), captures the level of complexity produced when we have no preconceived notion of the subject. The story is about a group of men who encounter a strange object in complete darkness. Because the storyteller is in the dark himself, he cannot provide a clue about the object. Here, all efforts to identify the object by touching its different parts prove fruitless until someone arrives with a light. The light, which in this context is a metaphor for methodology, enables them all to see the whole at last.

Rumi's version of the story illustrates that the ability to see the whole somehow requires an enabling light in the form of an operational systems methodology. In his mystical wisdom Rumi proposed that to get the enabling light one needed to tune in to the universe. For our purpose, the operational meaning of tuning in is that one should be able to make one's underlying assumptions about the nature of the sociocultural systems explicitly known and verifiable.

Whatever the nature of the enabling light, my contention is that it must have two dimensions. The first dimension is a framework for getting a handle on reality, a system of systems concepts to help generate the initial set of working assumptions about the subject. The second dimension is an iterative search process to verify and/or modify initial assumptions and expand and evolve the emerging notions until a satisfactory vision of the whole is produced. As beautifully put by Singer (1959): “Truth lies at the end, not at the beginning of the holistic inquiry.”

Three well-known inquiring systems (analytical thinking, synthetic thinking, and dynamic thinking), despite their success, have yet to agree on a method to see the whole.

Analytical thinking has been the essence of classical science. The scientific method assumes that the whole is nothing but the sum of the parts, and thus understanding the structure is both necessary and sufficient to understanding the whole. Synthetic thinking has been the main instrument of the functional approach. By defining a system by its outcome, synthesis puts the subject in the context of the larger system of which it is a part, and then studies the effects it produces in its environment. Dynamic thinking, on the other hand, has long been focused on process. It looks to the how question for the necessary answer to define the whole.

However, I contend that seeing the whole requires understanding structure, function, and process at the same time. They represent three aspects of the same thing and with the containing environment form a complementary set. Therefore, structure, function, and process with the context define the whole or make the understanding of the whole possible. Structure defines components and their relationships, function defines the outcomes or results produced, process explicitly defines the sequence of activities and the know-how required to produce the outcome, and context defines the unique environment in which the system is situated.

Use of all three perspectives of structure, function, and process as the foundation of a holistic methodology can be justified on both practical and theoretical grounds, as this chapter will demonstrate.

On more familiar and practical territory, we could observe that the classical school of management, with its input orientation, deals with structure. The neoclassical school, with its notion of management by objective, is concerned with functions. And the total quality movement, with its concern for control, is preoccupied with the process. Analysis, synthesis, and dynamics, each in its own right, have produced a great deal of information and knowledge. However, if we looked at the same phenomenon from all three perspectives of structure, function, and process at the same time, we could develop a more complete understanding of the whole. So, it is reasonable to conclude that a holistic approach must include all three notions of structure, function, and process.

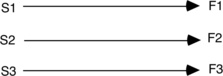

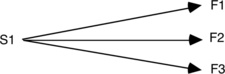

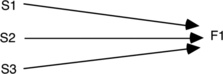

On theoretical grounds, we can reach the same conclusion with the following arguments. In a classical concept of reality, a specific structure (S) causes a particular function (F), and different structures cause different functions (Figure 5.1).

Therefore, it is assumed that to understand a system, we need to know only its structure. This is why analysis — understanding structure — is the dominant method for classical science.

But according to Ackoff (1972)

1. A given structure can produce several functions in the same environment (Figure 5.2). For example, the structure of the existing education system produces the functions of babysitting and buffer, in addition to the explicit function of transferring knowledge.

2. Different structures can also produce a given function (Figure 5.3). For example, the transportation function can be achieved by different means such as a train, plane, or car.

The classical notion of causality — where cause is both necessary and sufficient for its effect — proves inadequate to explain this phenomenon. Production of different functions by a single structure in the same environment can be explained only by the assertion that different processes were involved with the same structure in producing different functions. A simplistic example illustrates the point: a screwdriver can be used as a gouge, a chisel, a hammer, or a variety of other tools, depending on how it is applied.

This idea is compatible with the systemic notion of producers and product (Singer, 1959), which claims that a producer is necessary but not sufficient for its product. That is why a structure cannot completely explain its outcome and why we need the additional concept of an environment as a coproducer. However, when several outcomes are produced in the same environment by a given structure, then knowledge of the process becomes as necessary to understand the whole as the knowledge of environment, structure, and function. Structure, function, and process, along with the environment or context, form an interdependent set of mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive variables. Together, these four perspectives define the whole or make the understanding of the whole possible.

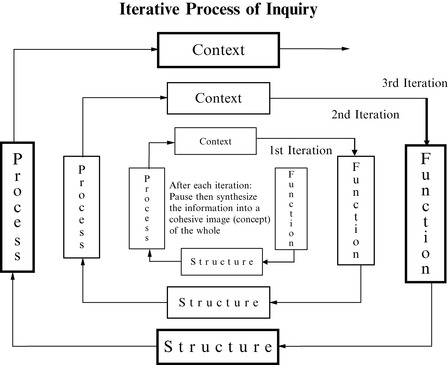

A set of interdependent variables forms a circular relationship. Each variable coproduces the others and in turn is coproduced by the others. Which one comes first is irrelevant because none can exist without the others. They have to happen at the same time. To fail to see the significance of these interdependencies is to leave out the most important challenge of seeing the whole. Therefore, to handle them holistically requires understanding each variable in relation to the others in the set at the same time. This demands an iterative inquiry.

Iteration is the key to understanding complexity. Stephen Wolfram (2002) demonstrated how an iterative process of applying simple rules is at the core of nature's mysterious ability to produce complex phenomena so effortlessly.

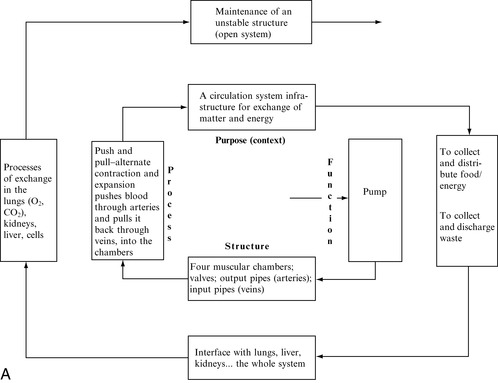

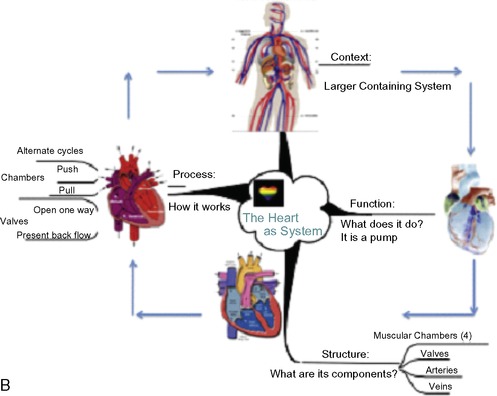

Iterations of structure, function, and process in a given context would examine assumptions and properties of each element in its own right, then in relationship with other members of the set. Subsequent iterations would establish validity of the assumptions and successively produce an understanding of the whole (see Figure 5.4).

For example, to appreciate the heart holistically, we must understand its function, structure, and process within the context of the body. Starting with the function we simply note that the output of the system is circulation of the blood; therefore, its function must be that of a pump. The structure of this pump consists of four muscular chambers and a set of valves, arteries, and veins. And the process, which must explain how the structure produces the function, simply uses alternating cycles of contractions and expansions of the chambers to push the blood through arteries and then pull it back into the chambers through the veins by suction.

Now we need to pause and relate our understanding of function, structure, and process together to appreciate why the heart does what it does. By placing the heart in the context of the larger system of which it is a part, we might conclude that the heart is at the core of a circulatory system. The purpose of the circulatory system is to exchange matter and energy between the body and its environment. This closely links the heart with autopoiesis, the self-generation of living systems (see Figures 5.5A and B).

The principle of iterative inquiry is reinforced by Singerian experimentalism: “There is no fundamental truth; realities first have to be assumed in order to be learned” (Singer, 1959). Successive iterations would yield a greater understanding and more closely approximate the nature of the whole. These iterations, then, are like a reverse zoom lens through which we see the system we are trying to understand as a working part of successively bigger and bigger pictures. We stop enlarging the view when we no longer gain useful insights as we “go around.”

5.2. Systems dimensions

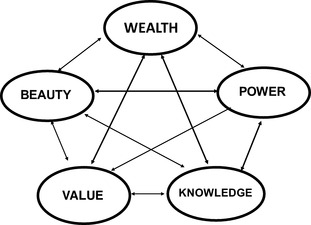

In addition to iteration of context, function, structure, and process we also need to identify and understand the parameters that coproduce the whole. These parameters, in my experience, are found in the interactions of the following five dimensions of a social system: wealth, power, knowledge, beauty, and values. The generation and dissemination of wealth, power, knowledge, beauty, and values form a comprehensive set of interdependent variables that collectively describe the social system in its totality (Figure 5.6).

Historically, the identification of social system dimensions has been both reactive (reacting to certain problems in social life) and proactive (reaching for the ultimate good). Reactively, the five dimensions of social systems correspond to the following major problem areas historically faced by all human societies: economics, scientifics, aesthetics, ethics, and politics.

Although some prominent social thinkers have implicitly considered more than one dimension in their analysis, most have chosen a single and, not surprisingly, different function as the prime cause of all social phenomena. Marx, for example, considered the economy, the mode of production, as the underlying cause of social realities. For Weber, power, supported by notions of authority and legitimacy, seemed the prime concern. Bagdanov used knowledge as the organizing principle of society. Meanwhile, religious thinkers place values at the core of everything.

On the proactive side, Ackoff, in his discussion of ideal-seeking systems, identified four classes of societal activity individually necessary and collectively sufficient for progress toward the ideal, or omnicompetence: the pursuits of truth (scientific function), plenty (economic function), good (ethical-moral function), and beauty (aesthetic function).

Coming from a different culture, I had a different point of view. In addition to knowledge, wealth, and values I included power, more specifically power-to-do (freedom and ability to choose), as a critical function of social systems. Surprisingly, I had missed the notion of beauty as a separate dimension.

When I met Ackoff, in the early 1970s, we argued over this for days, until he decided that I needed a good lecture on the subject. That lecture was beautiful, and I realized that I had missed the notion of beauty for exactly the same reason that Ackoff had missed the notion of power.

Thinking with my heart, I considered beauty to be the liveliness that defined life. Beauty for me was the whole, or the emergent property. On the other hand, the phenomenon of choice has been a major preoccupation of Ackoff's discussions. He saw the ability to satisfy needs and desires as being equivalent to competence. Competence for Ackoff was a matter of power-to-do (as distinct from power-over which is about dominance) and the emergent property of the whole. Maybe it is true that fish do not realize that something called water exists.

Revisiting Aristotle's concept of the “good life,” the pursuit of happiness, and his elaborate scheme defining the elements necessary to achieve a good life (Adler, 1978), confirms my earlier assertion that these dimensions may form a complete set and collectively define the whole.

Paralleling our five dimensions of power, wealth, knowledge, beauty, and values are Aristotle's association of liberty with choice and the willfulness to carry them out; his discussion of health, vitality, and vigor under the heading of wealth; the profound argument about the need to know and the skill of thinking; the assertion that a loveless life may not be worth living; and, finally, the magnificent notion of moral virtues (the good habits of choosing correctly).

In a different context, about 2,000 years later, John Dewey (1989), the great American philosopher, in discussing freedom and culture, explicitly refers to the states of politics, economics, science, art, and morality as the elements of the culture that determine the state of the society. His notion of art includes the sphere of emotionality, and in this context he argues convincingly that emotions are much more potent than reason in shaping public perception.

Recognizing these five dimensions as a mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive set, unlike those of conventional practice, is not meant to isolate each dimension so it can be analyzed separately. Rather, it is meant to emphasize their interactions. Although each dimension represents a unique functionality, interdependency among them is such that it is quite feasible for any four to become coproducers of the fifth one. For example, power, as the ability to do, can be positively or negatively influenced by wealth, knowledge, beauty (charisma), and values (tradition).

Recognition of multidimensionality and the imperative of and relationships among the five dimensions of social systems is one of the most significant characteristics of holistic thinking. Positive and negative feedback loops help to create stability and order while also creating synergy among the compatible dimensions, resulting in an order of magnitude improvement in systems performance. Systems theory of organizations maintains that major obstructions in development of sociocultural systems are the results of a malfunctioning in one or all of the five dimensions of social systems.

Finally, appreciation of the and relationship between the two functions of generation and dissemination in each dimension results in a whole new way of looking at our present set of problems and opportunities.

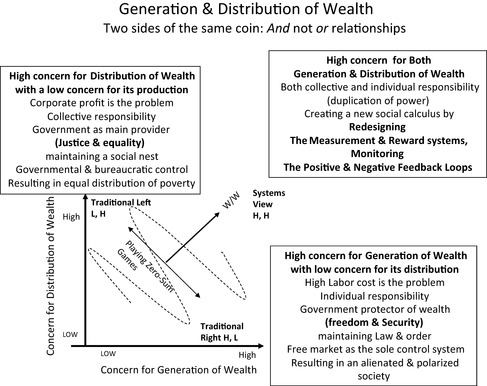

5.2.1. Generation and Dissemination of Wealth

Consider the classical question of generation and dissemination of wealth. Traditionally these two complementary functions have been treated as a dichotomy. On the right, high concern for generation of wealth combined with low concern for its distribution results in a position that considers the cost of labor as the source of the problem. It considers the individual to be solely responsible for his/her fortune and sees the role of the government to be only the protector of wealth and grantor of freedom and security by maintaining law and order. In this conception market is the sole arbiter for deciding what to produce, for whom to produce, and how to distribute the generated wealth, thus creating a polarized and alienated society.

On the other hand, a leftist orientation, with high concern for distribution of wealth, and taking the production of wealth for granted, looks at corporate profit as the source of evil. It considers the collective to be responsible for all misfortune and sees the role of the government as the main provider of justice and equality by creating and maintaining a necessary social nest. It considers governmental and bureaucratic control as the only remedy for limiting the inherent excesses of the corporate world, which unfortunately may lead to equal distribution of poverty.

But in reality generation and distribution of wealth are two sides of the same coin. Generation cannot be continued if there is no continued purchasing power to consume it. In the long run no society can continue to consume more than what it is capable of producing. Distribution without effective production can only result in equal distribution of poverty. True to the principle of multidimensionality, if we treat complementary pairs as a dichotomy we will surely find them to be in conflict. Fortunately, a high concern for both generation and distribution of wealth is also a strong possibility if we are willing to reward organizations not only for generation but also equally for distribution of wealth, for example, if our social calculus would permit us to consider certain types of payroll, in sectors with high unemployment rates, not only as cost but also as an output of the organization. This consideration would allow employers to deduct from their corporate income tax the equivalent of what their new hires (in the predefined categories) would pay in federal income tax. This would go a long way toward absolving the persistent 10% unemployment rate. With this scheme the amount of tax deductions by the corporation would be more than offset by the hired employees' federal income tax, payroll tax, state tax, and city tax payments. Government would save payment of unemployment benefits and the demand for goods and services will be enhanced by the newly added purchasing powers (Figure 5.7).

In the same context both collective and individual responsibility would be realized by the reconceptualization of the power dimension as power-to-do instead of power-over and by the notion of duplication of power. This observation brings us to our discussion of generation and distribution of power.

5.2.2. Generation and Dissemination of Power (Centralization and Decentralization Happen at the Same Time)

To deal effectively with multi-minded systems requires understanding choice, and choice is a matter of freedom and power-to-do. We have argued that while the parts of a multi-minded system increasingly display choice and behave independently, the whole becomes more and more interdependent. This represents a dilemma: a dichotomy of centralization (authority of the whole) or decentralization (autonomy of the parts). This dichotomy leads either to suffocation (concentration of power) or chaos (abdication of power). On the other hand, a compromise based on “sharing the power” produces frustration and gridlock.

The answer lies in the fact that centralization and decentralization are two sides of the same coin. Both have to happen at the same time. This phenomenon is possible because power is like knowledge. It can be duplicated. The conceptualization of power as a non-zero-sum entity is the critical step toward understanding the essence of empowerment and the management of multi-minded systems. Empowerment is not about the sharing of power. Sharing implies a zero-sum relationship and, therefore, abdication of power. Instead, empowerment is duplication of power in an organization or any sociocultural system. It requires a collective understanding of the reasons why we are doing what we are doing. Such a shared understanding not only empowers the members to act in harmony and autonomously, but also empowers the leaders to act effectively and decisively on behalf of the collectivity.

The following example illustrates this point. Suppose you have just started to work for a no-nonsense management-by-objective guy who has promised you that he will manage in a decentralized manner and will judge you only on the results. You look forward to this opportunity to try a few exciting ideas that require a degree of autonomy to be realized. After a few weeks you run into your new boss and decide to share with him some of the exciting things you have been doing. Although he attempts a poker face, you somehow sense he does not like what he is hearing. Maybe he is not in the right mood. You tell yourself, “When he sees the final results, he'll like it.”

A few weeks later, at a cocktail party, he seems very upbeat and you assume this might be a good time to share your new ideas with him. But he does not like them. Maybe you should leave him alone for a while, you think. But it is too late; he is already nervous. A few days later he shows up in your office and asks a few questions about some things you have proposed. When he leaves, you know he is not happy. Decentralization has gone out the window. You cannot risk being found incapable by the person who controls your future. So what do you do? You call him every time you need to make a decision to ask him what he wants you to do. You both become increasingly frustrated, and finally you decide to quit.

At this point a manager from another department reminds you that you have two kids in college and a mortgage to pay. She offers you a job if you are willing to forget the nonsense about decentralization and autonomy and do exactly what she tells you. Having no other choice, you reluctantly accept the offer. Your new boss, however, has a funny style. Not only does she tell you what to do, but she also tells you why she thinks this way. For a while you think she wants to brainwash you. Or maybe she is insecure and wants to prove something. You try to reassure her of your loyalty. “Just tell me what to do and I'll do it,” you tell her. But she will not give up. Apparently, she loves to talk. During these interactions, somehow, you find out how she makes decisions, you learn her decision criteria, and you begin to understand her value system. One day, when she's thinking out loud trying to tell you what to do, you ask her, “How about this?” She says, “Fantastic.” Decentralization happens.

The message of this brief story is that it is the sharing of decision criteria, not sharing or abdication of power, that results in empowerment and makes centralization and decentralization happen at the same time. Achieving a higher order of individual responsibility or decentralized decision making requires a higher order of collective responsibility or centralized agreement on decision criteria.

5.2.2.1. Design for participation: ackoff's circular organization

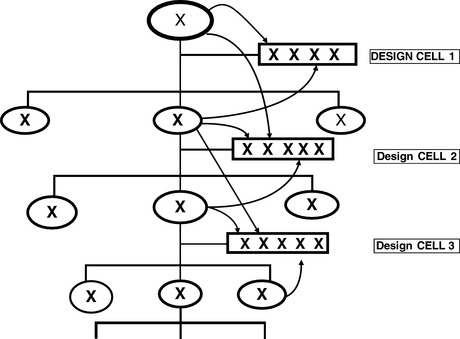

To produce a shared understanding of decision criteria among all members of an organization individually is an impossible task. The process of empowerment has to be institutionalized. The following scheme, known as Ackoff's (1994) circular organization, is a design for participation that has been used effectively in different contexts. It creates a nested network of “learning and design cells” that engage members in an interactive process.

Every manager in the organization forms a design cell. The membership of the cell will consist of the manager, his/her board, his/her boss, and all the direct reports (see Figure 5.8). Since every cell includes three levels of membership, a nested network is created. This provides an opportunity for everyone to interact with up to five levels in the organization (with peers on the same level, with the boss and boss's boss, and finally with the direct reports and their subordinates).

The main function of these cells is to create a shared understanding of why the organization does what it does, to develop an awareness of the default values of the culture, and to take collective ownership of the decision criteria.

5.2.2.2. Decision criteria

Decision criteria explicitly define the implicit rules of decision making, whereas decisions themselves are applications of the decision rule to specific situations. The absence of at least one degree of freedom virtually converts the decision criteria to decisions. A policy is a decision criterion at a higher level of abstraction. Policy essentially deals with choice dimensions (where variables are involved), why questions, underlying assumptions, and expected outcomes. Policy decisions are value-loaded choices that should be explicit about their implications for human, financial, and technical domains. To be effective, decision criteria should have the following four attributes:

Degree of Freedom: Decision criteria should leave a healthy degree of freedom for the decision maker. They should be specific enough to ensure consistency of action, as well as constancy of purpose and direction. At the same time, they should be broad enough to avoid straight-jacketing by allowing room for flexibility and learning. Degrees of freedom grant choice to the decision maker.

Consistency: Decision criteria should be internally consistent so that they do not create structural conflicts by introducing contradictory performance criteria. Examples include conflicts between input-based compensation and output-oriented performance or between cost centers (such as production units) and revenue centers (such as sales units).

Explicitness: Criteria to guide policy decisions ought to be explicit. They should reveal the assumptions on which the policies are made and spell out the expected outcome. The expectations should reflect at least these three areas: financial (financial performance), people (human system), and customer (quality of output).

Consensus: Effectiveness of any decision depends on the degree of consensus generated for it. The understanding and consensus reached in adopting a particular policy decision determine the level of collective commitment to that policy's implementation. Generating consensus is purely a matter of leadership. Here, as in many other issues involving rational, emotional, or cultural dimensions of behavior, the role of leadership is indispensable. It cannot be reduced to a magic formula. Ultimately, consensus will stand or fall on the quality of leadership. Consensus is not majority rule; it does not even imply unanimity. It is an agreement to act. No one should be allowed to take the process hostage. A “no decision” is a decision for the status quo, and it should therefore be acknowledged as such.

Situations that defy consensus call for leadership in its highest form. The absence of consensus would be a judgment call on the leader to ensure that the process is not hung up. He/she would then have to formulate an explicit working synthesis of the different positions that would be adopted as the default decision by the end of the session if the participants produce no alternative decision. When the group remains seriously polarized, the alternative is for the opposing parties to agree on an experiment whose result will produce the decision. The group should agree on the design of the experiment and specify its performance criteria. It is also very useful for the opposing parties to specify, up front, what will prove them wrong.

5.2.3. Generation and Dissemination of Beauty: Social Integration

The dimension of beauty is about the emotional aspect of being, the meaningfulness and the excitement of what is done in and of itself. It is about the imperative of “I like it” or simply the pursuit of pleasure. Maturana (1980) profoundly stated that, “The path of living systems in general, and human history in particular, is guided by emotions not resources. What guides this path is simple pleasure.” According to John Dewey (1989), “Emotions are much more potent than reasons in shaping public perception.” Avicenna, the famous Persian philosopher, reinforces this understanding of beauty by the assertion that, “The essence of life is love, love of beauty, and beauty is in the pursuit of wholeness.”

The understanding of holistic thinking cannot be complete without understanding the role of beauty in social integration. In contrast to machines in which integration of the parts into a cohesive whole is a one-time proposition, for organizations the problem of integration is a constant struggle and a continuous concern. Despite a desire for individuality and uniqueness, as emotionally vulnerable social beings we display a strong tendency to be members of a collectivity. Most of us have a burning desire to identify with others, to be accepted by others, and to conform to the norms of a group of our choice.

This integrative phenomenon seems rooted in the emotional dimension of our beings. An exciting book, objects of beauty, and a heroic or a tragic encounter all generate an urge to share. The boundary between individuality and collectivity — the question of how much of me is me and how much of me is those to whom I am bonded — remains at the heart of the manifestation of beauty. Beauty is, therefore, the most potent agent of social integration. The level of integration that an organization achieves depends on the level of excitement and commitment it generates among its members.

Recall that in the earlier discussion of development we identified desire as the essential ingredient for creation of an achieving society. Ability without desire is impotent, just as desire without ability is sterile. In this context aesthetics, contrary to popular belief, is not a luxury. Throughout history, societies that were antithetical to aesthetics invariably proved to be anti-human and anti-development as well.

5.2.3.1. Membership

The significance of membership in sociocultural systems (family, groups, organizations, nations) lies in the fact that the units of these systems are not the individuals but the roles imparted to them. Under different circumstances and in different social settings, individuals display different behaviors. A good friend is not necessarily a good employee. A successful vice president might make a lousy president. The nature of these roles is influenced by expectations and the limitations imposed by the social structure, the culture, and various environmental realities mapped by the actors.

Effective membership in a multi-minded system requires a role, a sense of belonging, and a commitment to participate in creating the group's future, so much so that rolelessness is the major obstruction to integrating a social system.

When an individual feels that his/her contributions to the group's achievements are insignificant, or when he/she feels powerless to play an effective role in the system's performance, a feeling of indifference sets in and the individual gradually becomes alienated from the very system in which he/she is supposed to be an active member.

In this context, the inability to carry out the responsibilities of a specific role (incompetence) results in anxiety and frustration. To fulfill the role of a physician or carpenter requires certain levels of expertise and mastery that must be learned. Otherwise, the individual to whom the role is entrusted will be alienated. As the strength of a chain is determined by its weakest link, incompatibility between the members often causes the more dynamic ones to retrogress to the level of the weakest, spreading a general feeling of ineffectualness and impotency. Conflicting values within a social system also contribute to alienating its members. The extent to which an individual's value image coincides with that of the community determines the degree of that individual's membership in that community.

A multi-minded organization is a voluntary association of purposeful members. The purpose of an organization, in addition to its own viability, is to serve the purposes of its members while serving the purposes of its containing whole. Members join an organization to serve themselves. Unless the organization serves them, they will not serve it well.

Although it is possible to persuade purposeful members of a purposeful social system to engage in a sacrifice for a limited time, it is highly improbable that they will accept this condition as a way of life. There needs to be an exchange system so that the individual's struggle for his/her own gain is enhanced by the degree of contribution he/she makes toward satisfying the needs of the higher system and those of the other members.

Nevertheless, proper functioning of a multi-minded organization also requires an implicit threat system. In other words, continued membership in a system should depend on avoiding a certain set of behaviors considered antagonistic to the survival of the whole. For an elaborate treatment of role, exchange, and threat see Boulding (1968).

5.2.4. Generation and Dissemination of Knowledge

The success of any social system will ultimately depend on its ability to generate and disseminate knowledge, which requires a three-dimensional learning system.

Learning to learn is about the ability to learn, unlearn, and re-learn, both within and beyond conventional frameworks. Given the accelerated rate of change that keeps transforming everything in contemporary life, the real competency of the knowledge dimension is to produce self-directed learners. To relearn one has to unlearn first and, unfortunately, unlearning is much more difficult than learning. One might have to go through a lot of trouble to undo what previous wrong learning has done to him/her.

Learning to be covers the whole spectrum of learning experiences that result in both individual and collective development in quality-of-life-enhancing activities that involve pleasure. It is about desires as well as abilities; more about content than capacity, direction rather than speed; why rather than how; it is about life, about explicitly understanding the state of being and the process of becoming. Learning to be, in essence, is about values, worldviews, cultures, and identities; more specifically it is about having the courage to question the sacred assumptions. If history is a lesson, national declines are preceded by cultural stagnation.

Learning to do is about competency to operationalize knowledge, to define problems and design solutions in the real and messy world. But the problems in the real world do not divide themselves the way universities do. Traditionally, learning to do happened most effectively in the work environment and businesses provided this function. When I joined IBM in the 1960s, the assumption was that I would be working for them for 30 years. That is why they invested more than 1,800 hours of formal training to make me a systems engineer. Unfortunately, abdication of this critical responsibility by business along with a proliferation of the number of specialists who enjoy knowing more and more about less and less and their implausible inability to connect the necessary dots is becoming a major concern. Learning to do is about acquiring the ability to relate one's special text to its proper contexts, and to understand how the other related parts or actions coproduce the whole and how action of each part is affected by actions of the others. After all, no problem or solution is valid free of context. Operational thinking (subject of Chapter 6) tries to over come this deficiency.

5.2.5. Generation and Dissemination of the Value: Conflict Management

When parts of a system display choice, conflict among them is inevitable. The ideal of a conflict-free society not only is not feasible, but it is not even desirable. A conflict-free system will only be possible if the behaviors of its members are reduced to a robotic level. The answer is that sociocultural systems should develop the capability for continuously dissolving conflicts.

To integrate a multi-minded system is to design an organization whose members can operate as independent parts with individual choices while simultaneously acting as responsible members of a coherent whole with a collective choice.

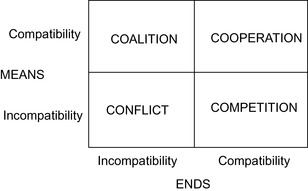

The effectiveness of an organization, therefore, depends not so much on managing the actions but on managing the interactions among its members. The interactions among members of an organization take many forms. Members may cooperate with regard to one pair of tendencies, compete over others, and be in conflict with respect to different sets at the same time. In general, by agreeing or disagreeing with each other on compatibility of their ends, means, or both, actors (individually or in groups) can create four types of relationships: conflict, cooperation, competition, and coalition1 (Figure 5.9).

1Definitions for cooperation, conflict, coalition, and competition as well as those for solving, resolving, dissolving, and absolving are from On Purposeful Systems (Ackoff, 1972).

• In conflict, each party reduces the expected value of the outcomes for the others. The opposite is true of cooperation. Competition represents a situation in which a lower level conflict serves the attainment of a commonly held higher level objective for both parties. It is a conflict of means, not ends. Coalitions are formed when actors with conflicting ends agree to remove a perceived common obstruction. In this unstable situation, conflict is temporarily converted to cooperation, only to be succeeded by possibly more severe conflict at a higher level.

• If organizations are to serve their members as well as their environments, they must be able to deal with conflict. Creating a conflict-free organization may not be possible, but creating one capable of dealing with conflict is.

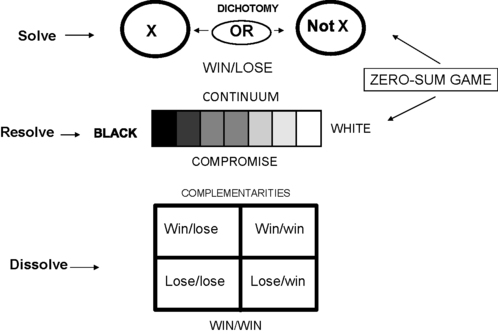

• Conflict can be addressed in four different ways: solve, resolve, absolve, or dissolve (See Figure 5.10).

• To solve a conflict is to select a course of action believed to yield the best possible outcome for one side at the cost of the other; in other words, a win/lose struggle.

• To resolve a conflict is to select a course of action that yields an outcome good enough and minimally satisfactory to both the opposing tendencies; in other words, a compromise.

• To absolve a conflict is to wait it out, hoping that, if ignored, it will go away; in other words, a benign neglect.

• To dissolve a conflict is to change the nature and/or the environment of the entity in which it is imbedded, thus removing the conflict.

Selecting any one of these courses of action depends on how the relationships between opposing tendencies are formulated. As discussed earlier (under the principle of multidimensionality), these relationships are conceived in at least three ways: dichotomy, continuum, or multidimensional scheme. Dichotomy represents an or relationship, a win/lose struggle. This calls for a solution to the conflict. The loser, usually declared wrong, is eliminated. Continuum calls for a compromise, or resolution of the conflict. For multidimensional concepts, however, interaction between opposing tendencies is characterized by an and relationship. This formulation permits the conflict to be dissolved.

When the conflict situation is formulated as a zero-sum game, gain for one player is invariably associated with a loss for the other. But in the multidimensional concept, a lose/lose as well as win/win, in addition to win/lose struggles, are strong possibilities. Therefore, a loss for one side is not always a gain for the other. On the contrary, both opposing tendencies can increase or decrease simultaneously.

To dissolve a conflict is to discover new frames of reference in which opposing tendencies are treated as complementary in a new ensemble with a new logic of its own. It requires reformulation or, more precisely, reconceptualization of the variables involved.

Finally, to dissolve a conflict is to redesign the system that contains the conflict, creating “a feasible whole from infeasible parts.”

5.2.5.1. From lose/lose to win/win environments

An important characteristic of a win/lose struggle is the possibility of converting it to either a lose/lose or a win/win environment. In today's complex and highly differentiated social systems, emergence of a lose/lose environment is not only highly probable, but it is an increasingly dominant reality.

Today, winning requires much greater ability than ever before. It is easier for groups to prevent others from winning than to win themselves. Increasing numbers of small special interest groups are diluting the strength of the traditional power centers. Even many disadvantaged minorities have been forced to learn how to keep the opposing sides from winning. The illusion that increased losses for the other side is equivalent to winning is what prolongs the struggle and forces the game to be played to a lose/lose end. Ironically, it is awareness of this high probability for lose/lose that becomes instrumental in converting a win/lose to a win/win. This is easily confirmed by understanding the reason why the players in the famous prisoners' dilemma (Rapoport, 1965) chose the win/win strategy to avoid a lose/lose end. Dynamic interaction of the players, combined with awareness of a possible lose/lose situation, creates a meta-game leading to selection of a win/win strategy.

5.2.5.2. Changing conflict to competition

Ends and means are interchangeable concepts. An end is a means for further ends. Changing conflict to competition requires finding higher level objectives shared by lower level conflicting tendencies. The lower level opposing ends are converted into conflicting means with a shared higher level objective, resulting in competition.

The search for finding a shared higher level end can continue up to and include the ideal, when ends and means converge and become the same. The probability of finding a shared objective increases by moving to higher and higher levels. It is maximized at the ideal level. Now, if even the ideal level cannot produce a common end for conflicting tendencies, then the conflict is considered non-dissolvable within the context of existing worldviews. In this situation, dissolving the conflicts requires a change of worldviews. This change can be a reaction to frustrations with the existing assumptions' failure to deal with a new era, a march of events nullifying conventional wisdom, or it can happen by an active learning-and-unlearning process of purposeful transformation.

5.2.5.3. Democratic challenge

For a viable society based on democratic conventions, it is crucial to define the notion and parameters of majority rule. It is imperative to forge a widespread agreement on what constitutes a legitimate majority: its powers, its boundaries, and whether it has a right to override the individual or trample minorities in the name of the whole. It should define the limits of the minority and majority rights so that they may complement, rather than encroach on, the rights of others. If the rule of law finds its legitimacy in the will of the majority, then tyranny of the majority would already be an accomplished fact unless it transcends, and reigns supreme over and above, the majority itself. The majority, for example, has no right to disown its right to democracy and, thus, democratically undermine democracy itself.

The individual and the collectivity both have separate, and yet interrelated, rights and responsibilities. Not only are these two sets of rights and responsibilities not exclusive, but they are essentially complementary. They are so interdependent that one could not be dealt with without touching the other.

Collectivity has distinct rights to security, viability, and sovereignty. It has a right to act; its decision process cannot be taken hostage. It is also responsible for making sure that the individual, even as a minority of one, is provided with enough alternatives to make his/her choices meaningful.

An individual citizen has inalienable rights, such as the right to privacy and the right not to be discriminated against. In addition to these rights, an individual can enjoy certain privileges, which he/she may acquire or lose, provided certain conditions are, or are not, satisfied. An individual, however, stands to lose the privileges that he/she abuses; irresponsible driving would be one obvious example.

..................Content has been hidden....................

You can't read the all page of ebook, please click here login for view all page.