Chapter 11. Butterworth Health System

Butterworth Health System redesigns itself around a concept of care that makes a significant break from the current practice. The present health-care system has its origin in sickness care. The cost-recovery aspect of a sickness-based health-care system has been associated with three basic conceptions — fee for service, cost plus operation, and third-party payer — with no mechanism of self-control. The system has fueled an insatiable demand with an uncontrollable increasing cost. The new design tries to dissolve the structural conflict among patients, providers, payers, and administrators of the health-care system in such a way that they complement each other without any of them being compromised. A multidimensional architecture explicitly identifies the value chain, the critical dimensions of the care system, and how different stakeholders relate to one another. The architecture is intended not only to dissolve the existing “mess” but also to transcend it by developing a vision of the next generation of a health-care system.

Keywords: Capitation, Community-based health-delivery system, Conflict, Core knowledge, Cost plus reimbursement, Coverage card, Depersonalization of care, Disenfranchised, Fee for service, HMO, Home care, Hospitality management, Insatiable demand, Interventional care, Knowledge bank, Learner/educator, Managed care, Medicaid, Medicare, Modular structure, Occupational care, Preventive care, Risk distribution, Sickness care, Specialized health delivery, Structural terminal care, Third-party payer, Value chain, Viability care

This report summarizes Butterworth's attempt to redesign itself around a concept of care that makes a significant break from the current practice. The report projects a shared vision of Butterworth's desired future. It is produced by active participation of the design team. Members representing Butterworth are Katy Black, Sharon Buursma, Priscilla A. Dakin, Roy Eickman, Michael Freed, William G. Gonzalez, Joyce Henry, Jean Hitchcock, Pat Marks, Philip McCorkle, Irma Napoli, Tom Ouellette, Jon Ganz, M.D., Ray Gonzales, M.D., Brian Roelof, M.D., Suzanne Rogers, Joel Sacks, M.D., Carol Sarosik, James F. VanDam, M.D., Fred Vandenberg, and Randy Wagner. Members representing INTERACT are Jamshid Gharajedaghi and Bijan Khorram.

The design represents six iterations directed at generating consensus on the following key points:

• Shared understanding of the issues, concerns, and expectations of those who have a stake in the organization

• Shared understanding of the emerging health-care environment

• Identification of the purpose and strategic intent of the system

• Identification of the specifications of the desired system

• Development of the systems architecture (major components and their relationships)

To meet the space limitations of this book, 200 pages of design document had to be condensed to 40 pages. To minimize the compromising effect on the design as a whole, the main reductions were focused on the marketing, administration, and governing dimensions of the architecture. Inevitably in the process, some very interesting ideas have been lost or misrepresented. I hope that the design team will accept my apologies for this.

11.1. Issues, concerns, and expectations

The present health-care system has its origin in sickness care. It was designed to provide service to those who fall ill and need medical care. The cost-recovery aspect of utilizing sickness-based health care has been associated with three basic conceptions: fee for service, cost plus operation, and third-party payer, as defined in the following:

• Fee for service is an exchange system in which charges are proportional to the level of services rendered.

• Cost plus is a pricing mechanism in which the incurred costs plus a markup designed to cover the overhead and margin are summed up to define the value of the output.

• Third-party payer is an institutional arrangement in which the receiver of the service (the consumer) is not the same as the payer (customer). The arrangement transfers the costs to the institutional customer (insurance companies and government), who in turn transfers them, indirectly, to ultimate payers and the public at large.

The current model has no built-in mechanism of self-control to discipline the relationship between the provider and the patient. It has created a positive feedback loop that has fueled an insatiable demand for more services. The demand feeds on itself as long as patients are willing to ask, providers are eager to serve, and third-party payers do not mind picking up the tab and adding a margin before passing it on to the ultimate payer. In such a context, demand cannot be rationalized.

Advances in technology have expanded the possibilities for continuous medical breakthroughs. As a result, life expectancy has increased and the desire to delay the final exit has caused the demand for technology to grow exponentially. However, technology can only delay the final exit at exorbitant costs, and every time it does it further fuels the insatiability of the demand. This exponential growth in demand for postponing the eventuality at all costs cannot be left unchecked — especially if costs are conveniently passed to a third-party payer, leaving the demanding population under the illusion of a continuous free lunch.

The system seems to have hit its upper limit. Alarmed by the long-term consequences of its own irresponsible demand for more, better, and costlier care, the stakeholders of the system have begun to apply the brakes. This has forced the growth curve into an S-shaped form.

The first corrective action against this runaway escalation has been the introduction of HMOs to manage care. To reduce the rising costs of care, one has to begin to manage the care, since 85% of the operating expenses were assumed to be the cost of goods (care). The majority of HMOs, however, have not been successful at managing care. Instead, they have relinquished this responsibility by moving into a contractual mode that exchanged volume for wholesale discounts. Thus HMOs have achieved economies of scale by delivering their captive customers to the health-care system. Although this has reduced the rate of growth, the pressures to contain costs have continued and the idea of managing care has resurfaced. HMOs have been forced to use a bureaucratic system and a mechanistic mode of operation to manage the most emotional and sensitive behavior of a human system of health care.

Not surprisingly, the mechanistic management of care has been received with resistance. The idea of a bureaucrat telling the health-care system what to do, or not to do, proved unacceptable for the two critical stakeholders: the patient and the provider. Although some HMOs have developed more elaborate models to manage care, they have retained their bureaucratic character and have operated within a mechanical framework. Structural conflict, compounded by intractability of developing a simple mechanistic solution to what is essentially a complex living phenomenon, has led to the abdication of the problem. The emerging response yielded itself to the concept of capitation (per-head payment), pushing the decision and the financial risk lower in the supply chain to the provider level.

In a parallel development to capitation, the concept of preventive care has emerged as an effective way to control costs. HMOs got into the act by default and broadened the notion of health care to include wellness. The combination of wellness with capitation had promised to be an effective solution to the problem of depersonalization of care by removing the bureaucrat as an intervening agent between the patient and the provider.

This could have proved effective as long as the service was limited to preventive and normal care and was carried out in the context of a generally healthy population with a normal risk distribution that could easily be assessed and managed. However, when the treatment of acute cases is mixed in with the routine practice of health maintenance, the notion of risk management takes on a whole new significance. In the conventional capitation model, the patient population is distributed among the primary care physicians with a fixed payment per member. The smaller the population, the higher the risk. This is contrary to the notion of insurance, which is to reduce risk within a large population. Otherwise, the idea of insurance would be pointless.

To overcome the problem of risk in subgroups assigned to primary care physicians, some HMOs have provided a special case approval process. As a consequence, in cases that involve life and death decisions, the system once again refers the responsibility back to its mechanistic bureaucracy. Thus the old problem of conflict is renewed not only between the physician and the patient but also between the physician and the insurance company.

To aggravate the situation further, the supposition that the primary physician will pay for the services of specialized care throws the sensitive patient–physician relationship, as well as the general practitioner–specialist relationship, into suspicion and controversy. The mere perception of a conflict of interest, even if unfounded, is not helpful in a relationship that should be based upon unshakable trust. Trust among major stakeholders (primary care physician, medical specialist, and patient) is the most crucial element for the success of any health-care model. Any notion of structural conflict will disrupt the whole system. Until the system comes of age, such suspicions should be preempted. This would imply the need to create enough safeguards to make sure that proper functioning of the system is not compromised.

The major overhaul of sensitive institutions, foremost among them the health-care system, should consider the risks of social experimentation. Interventions into social contexts, once brought into existence, tend to take on a life of their own. When a cause goes away, its effects do not necessarily go away. In social domains, cause and effect are separated in time and space. Consequences of an action may take some time to realize; therefore, any new design should be kept deliberately open, flexible, and mindful of irreversible consequences of its actions.

The new design should create an opportunity for a well-balanced approach. It should avoid alternating between extreme concerns in one direction followed by subsequent reversals in the opposite direction. The virtues of fee for service, capitation, and other useful concepts should be incorporated into an encompassing system that will allow for choice and adaptive behavior without an endless series of disruptive fluctuations along the way. The system should expand its sources of variety by incorporating different alternatives and evolve through continuous selection and learning.

11.2. Design specifications

The new system should:

• Rationalize the relationship between supply and demand in such a way that the patients receive optimum quality care without fueling an insatiable demand for wasteful services

• Utilize advanced technology to provide the best possible care without creating unreasonable expectations

• Dissolve the structural conflict among patients, providers, payers, and administrators of the health-care system in such a way that they complement each other without any of them being compromised

• Maximize the flexibility and responsiveness of the system and take full advantage of the existing and emerging possibilities in the health-care market

• Be capable of continuous learning, adaptation, and renewal

• Represent the state-of-the-art in health delivery management without getting sidetracked into irrevocable social experimentation

• Contain and dissolve the pre-existing conditions (the mess) in the current institutional setup while preventing them from spilling over into the newly created components

11.3. The architecture

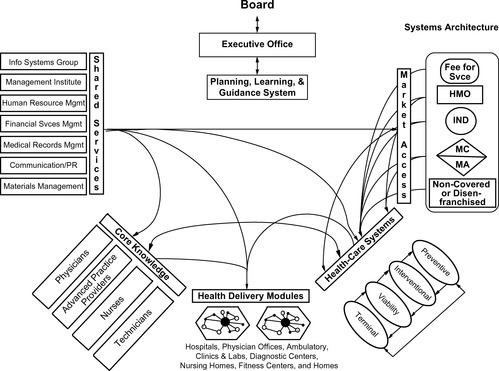

The systems architecture (Figure 11.1) identifies the value chain, the critical dimensions of the health-care system, and the way it relates users to providers in the health-care system. In order to create an architecture that will realize the expectations and desires of Butterworth's stakeholders, the designers recognized the necessity of employing a multidimensional scheme. Such an architecture is intended not only to dissolve the existing “mess” but also to transcend it by developing a vision of the next generation of a health-care system.

The architecture represents a platform from which Butterworth's distinctive value chain will evolve. The value chain identifies all of the elements of the health-care system and their relationships along a market dimension (access and care systems), an output dimension (health delivery modules), and an input dimension (core knowledge and shared services).

This multidimensional framework not only helps the designers understand and differentiate each component of the system, but also establishes the components' relationships in such a way that an integrated and cohesive whole can emerge. Design and incorporation of the missing elements, which can be identified by an analysis of the value chain, will lead to a value-adding system in which the value generated by the whole will be greater than the sum of the values produced by the parts.

11.4. Market dimension

The market dimension deals with the users of the health-care system. A market is defined in terms of three essential elements: need, access, and purchasing power.

The classification and proper grouping of health-care needs define the nature of products and services rendered. These will be discussed in detail under the following section on the care system. However, the classification of users into various groupings reflects their purchasing power and defines the market access mechanism necessary to reach them.

11.4.1. Market Access

Users of the health-care system are traditionally grouped into the following institutional models.

11.4.1.1. Fee for service

The traditional insurance companies such as Blue Cross and Blue Shield usually represent fee-for-service arrangements. Members are free to choose their own providers, who are compensated on a cost plus basis. Blue Cross/Blue Shield of Michigan has converted to a managed payment system; it pays on a diagnostic-related group (DRG) basis. This arrangement has caused the development of the interventional care system.

11.4.1.2. HMOs

HMOs were designed as a way to curb the rising costs of health care by managing the members' health-care demand needs. They contract for care on a discounted basis from providers. HMO patients are limited to a preselected group of providers. In evolving HMOs, the providers are given a fixed per-member sum, called capitation, to be drawn against for services rendered. Although originally sick-care oriented, HMOs have begun to build prevention, maintenance, and wellness into their services to curb the treatment costs — hence the term “managed-care plans.”

11.4.1.3. Independents (self-insured)

The independents, or self-insured populations, include employers who finance health-related charges for their members based on the plans they design for themselves. They may choose to outsource the management of their system to HMOs, to other insurance companies, or to third-party administrators (TPAs). To serve this group effectively requires a great degree of flexibility because each represents a variety of different designs.

11.4.1.4. Medicare

Medicare is a federal government health insurance plan for those who have reached a certain age (around 65) and have contributed the minimum premiums required to the fund. Medicare is beginning to move patients toward managed-care plans.

11.4.1.5. Medicaid

Medicaid is primarily a state government health insurance plan for those who lack the resources to take care of themselves. It also provides nursing home funding for long-term maintenance for the poor. Some state plans are also beginning to move patients toward managed-care plans.

11.4.1.6. Noncovered customers

Noncovered customers are disenfranchised individuals who are not members of any insurance plan. The care for these individuals is important to the health system. They ultimately receive care through emergency rooms and inpatient hospitals that receive little or no reimbursement.

Butterworth Health System may take the initiative to design and experiment with a select neighborhood group of noncovered customers and provide them with a Butterworth Health Coverage Card. This program would explicitly address the mission of Butterworth to serve the community, irrespective of ability to pay. The program would be financed by Butterworth and/or the Butterworth Foundation. Later on, the program could be extended to include other underserved populations in the community. Creation of this program would not only make it possible to treat the disenfranchised as any other client, but would also make Butterworth's contribution to the community visible and measurable.

The key responsibilities of the market access function will involve the following: market assessment, packaging, product/market negotiations, customer/consumer satisfaction assessment, and health-system marketing.

11.5. Care system

As one of the basic dimensions of the Butterworth architecture, the care system will be responsible for defining and monitoring the virtual output of the system. By doing so, it will bridge the gap between the market and the actual delivery of health-care products and services.

The design of the care system in this format embodies a set of conceptual models, methodologies, and products that represent the operationalization of a distinct system of health delivery management. Such models and methodologies include care management, risk management, quality management (utilization), and referral protocols. The provision of actual care, however, happens at the health delivery modules.

11.5.1. Contextual Background

For the health-care system to deliver its intended goods, it has to deal with both maintenance of health as well as treatment of sickness. The present health-care system is primarily concerned with taking care of the sick. It has evolved into a mature and entrenched system characterized as sickness care. The overwhelming success of sickness care has, as financed by historic reimbursement methods, obstructed and even prevented development of other critical aspects for the creation of a well-balanced health-care system.

Despite the fact that health maintenance and preventive care have long been recognized as an effective means of cost control, development of a significant wellness subsystem is practically nonexistent in the health-care system. Few have taken it upon themselves to address the traditional concept of “care” and develop the necessary operational protocols because of lack of adequate funding sources. Development of the care system, as presented here, will fill the chronic void in the health-care environment by introducing a bold, pragmatic dimension.

The conventional approaches of changing the way we pay for health care in and of themselves will not reform the system in the desired direction. Their focus is essentially on payment arrangements. Payment, while important, is but one of the concerns. A comprehensive approach should address the totality of a given care system, including financial as well as operational, technical, and behavioral viewpoints.

11.5.2. Desired Specifications

The care system deals with people when they are most vulnerable. It will involve the most sensitive aspect of people's lives. The design, therefore, should proceed with care because social institutions, once created, cannot be easily undone. The care system should therefore represent a comprehensive framework that will:

• Capture the missing dimension in the total management of care — the intervening link that can dissolve possible structural conflicts in the system and create win/win solutions among the patient, provider, and payer

• Be viable in the current environment, but will also be capable of continuous learning and adaptation in changing environments

• Allow maximum flexibility for the patient and the payer to exercise choice in terms of required services (selection of care module), access (selection of provider), and payment arrangements (selection of capitation and/or fee for service)

• Center around product differentiation, product development, and product management to enable each of its constituent modules to:

• Represent a unique category of care; while individually independent, collectively they will create an integrated whole

• Follow a model of reimbursement that will best optimize multiple objectives of the care system (cost, quality, simplicity, and, most important, avoidance of structural conflict between payer, patient, and provider)

• Become infrastructure-free, allowing maximum choice in selection and utilization of various care facilities, such as hospitals, homes, clinics, and care centers

• Be a decentralized and regionalized community-oriented health delivery system in order to be able to develop rapid and differential responses to its existing and potential communities with different health-related needs

• Keep all its options open and remain agile and flexible enough so it can take advantage of the emerging opportunities in the rapidly changing and unpredictable health-care environment

• Benchmark its performance against relevant state-of-the-art criteria by making sure that (1) the health-related aspect of the health delivery system (HDS) is targeted at the best performance within the industry and (2) the support services, such as the administrative services, hospitality and facility management, and information systems, are targeted at the best performance outside the industry

• Achieve an order-of-magnitude improvement in the cost-effectiveness of operating facilities by redesigning the throughput system

• Adopt and operationalize a new social calculus to encourage identification and elimination of waste and value-chain transaction and capacity utilization

• Replace the dysfunctional matrix organization (two-boss system) with an exchange-based customer–supplier relationship to dissolve structural conflicts and create a win/win environment compatible with the systems architecture.

Observation of the previous criteria led to the following design and classification of the care system as

• Preventive

• Interventional

• Viability

• Terminal

To be effectively cultivated, the care system modules will be initiated and operationalized into separate but interrelated modules. Initially, these modules will be created or redesigned outside of the current environment, under a different set of performance criteria to provide incentive for them to serve the needs of users, providers, and customers (payers) at the same time. Later on, the components can be unified or separated or further differentiated. Unification of the care system's modules, at least at the embryonic stage, will be avoided because it would lead to unbalanced development of one module at the expense of others. For example, the existing size and format of the interventional care module has the potential to obstruct the healthy evolution of the newest modules.

11.5.3. Common Features

The following will be common to all modules of the care system:

• Each care system module will have the requisite flexibility and capability to deal with the capitated model, the fee-for-service model, a combination of the two, or any emerging variation that could prove operationally sound. The care system modules will therefore have mechanisms that will give them the necessary flexibility to deal effectively with the emerging possibilities and make the necessary transitions with ease.

• Each care system module will also enjoy the freedom and responsibility to make its offerings available through the market access dimension to any segment of the market that may promise potential clients. The product (care system module) managers will not, therefore, be limited to a single channel of HMO in their marketing efforts. They can take advantage of different access mechanisms to deal with independent institutions or individuals.

• The care system modules will require the development of an interactive model of operation that will open the system to not only capitation and fee-for-service populations, but other potential groups such as independent contractors with different interests and requirements.

• Development of the care system is essentially the development of a product line. Each care module will therefore have a product manager operating under a board representing the relevant stakeholders of that dimension, including physicians, nurses, financial and support services, and so on.

• Each care system module will be designed to be a member of an integrated whole while being managed as a stand-alone entity. It will be responsible for its own cash flow and financial performance. If any one module cannot stand alone financially, the system can decide whether to subsidize or redesign the module.

• Each care system module will have a financial model that will preempt structural conflict by aligning the interests of the major players actively involved in the delivery of care: the provider, the patient, and the payer.

• A target costing system will be developed to determine the relative share of each subsystem in the provision and distribution of care. The cost-sharing model will determine the costs of goods, selling, care, shared services, product development and maintenance, and facilities.

• Each and every module will have its own share of indigent patients who will be served in an environment that will promote personal responsibility and self-reliance.

• The health-care system will encourage and register the clients to sign up for a total care package: preventive, interventional, viability, and terminal care. However, customers would have choice among services offered.

• The pricing model should make it cheaper to purchase the product offerings as a total package rather than selectively or on a partial basis. The cost of interventional care, the largest portion of care, will therefore be significantly reduced if the customers are encouraged to buy other pieces as well. Thus, the impact of imposing a disproportional allocation to the rest of the system would be significantly reduced whenever a group of customers happens to opt for partial, rather than total, access.

• Protocols will be formulated to make explicit the predefined sequence of procedures as each type of patient is processed through the system.

• Each care module will have the responsibility of defining its information requirements and working closely with the information system unit to develop an interactive and comprehensive information support system that will not only service all the care system modules, but all the care providers as well. This information system will act as an input to the learning system. The care system, in essence, will act as a customer of the information system unit and present a major market for information-based products.

• Each care system module will be equipped with an embedded learning system. The system will have explicitly stated assumptions and expected outcomes. It can and will modify itself based on the inputs that come from continuous monitoring of the actual performance and its comparison with the initial assumptions and expectations.

• The reward and evaluation of the care system and its modules will operate on three levels:

• At the throughput level, the care system rewards will be based on the measure of the volume processed and its effectiveness.

• At the latency level, the care system module rewards will be based on the measure of outcome, quality, and effectiveness of the care system as manifested in the general health of the population covered.

– At the synergy level, the care system module rewards will be based on the measure of effective cooperation and collaboration shown toward other parts of the care system in particular and Butterworth system as a whole.

Descriptions of individual care modules follow.

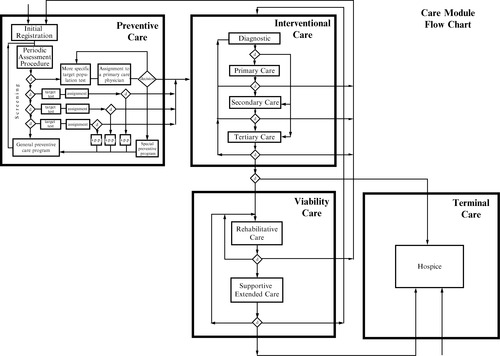

11.5.4. Preventive Care

Preventive care will be responsible for maintaining and improving the health of the covered population as a whole. It will carry out this function by

• Maximizing the health of anyone who comes into the system.

• Keeping those who are free of illness and injury from developing diseases or having disabilities.

• Detecting at an early stage those who are already sick and limiting further illness episodes through early intervention and other preventive measures.

• Developing protocols that will define recommended sequences of procedures for registering, identifying, and directing target groups of patients to appropriate centers staffed by appropriate providers based on initial assessment results, while respecting and supporting the right of each patient to exercise informed choice.

• Developing a measurement and evaluation system that will reward successful incidents of early detection.

• Maximizing patients' choice by providing them open access to clinical expertise; based on the screening results, the system will identify and target the patients who will then be advised to follow a preferred course of action under a recommended primary care provider.

11.5.5. Interventional Care

Interventional care is responsible for restoring the health of patients by offering a continuous and/or intense level of care. The interventional care will consist of the following levels of care: primary, secondary, and tertiary. While primary care will serve as an access point for ambulatory patients with non-life-threatening problems/symptoms, secondary and tertiary care will involve intensive intervention extending over a relatively short period of time.

The basis for care differentiation will be the degree of need for continuous nursing care and a specialty provider(s). These different levels of care can be addressed by the same or different providers/care givers carrying varying costs.

Interventional care will be responsible for the following:

• Develop a treatment plan defining the involvement of specialists, support staff, facilities, and referrals and/or discharge plans.

• Reimbursement for interventional care will likely be a hybrid. While the primary care can be capitated as a whole, secondary and tertiary care may utilize a version of the fee-for-service arrangement by means of a trust fund. This will provide the flexibility to:

• Deal with the complexities of a treatment program due to inherent uncertainties and the number and varying degrees of other providers involved.

• Manage the risks involved when small groups of patients may require treatments that are extremely expensive.

• Remove the potentials for structural conflict and avoid the suspicion on the part of the patient or a participating provider that the payer may have any ulterior motive in defining the planned prescriptions.

– Optimize interventional care expenses both at the aggregate and individual levels. The patient's well-being will not be compromised because the risks will be shared between the system and individual providers.

11.5.6. Viability Care

Viability care is responsible for restoring functionality (temporary or permanent) to the maximum extent given the nature of the underlying physical limitations. Functional limitations may occur due to accidents, sickness, birth defects, or old age. Viability care will provide:

• Prognosis for (1) potential functional improvement and (2) the prospect of returning to home/community based on medical, psychosocial, and economic resources

• Assessment, treatment/equipment, infusion therapy, education, psychiatric therapy, monitoring, and hospitality services, if homeless

Viability care will consist of two levels of care: rehabilitative and supportive. While rehabilitative care will involve revitalizing the patients by removing their functional limitations, supportive care will involve keeping the existing levels of irreversible physical limitations from deteriorating further. At the same time, supportive care will also involve keeping the patients from contracting other illnesses while providing them with compensatory support to help them perform their basic functions. Differentiation between the two levels is based upon the duration of care and the chance of recovery from functional limitations.

Figure 11.2 shows the pattern of interactions both within and between the parts of the care modules.

11.5.7. Terminal Care

Terminal care is responsible for developing humane, dignified, and cost-effective means of taking care of patients who are diagnosed to be irretrievably moribund. The function of terminal care will be to

• Support patients and families through the death experience (choices)

• Provide education and counseling (psychological and legal) to care givers

• Build cost-effectiveness into managed care

Historically, the cases of terminally ill patients have presented the health profession with one of its most complicated dilemmas. Health-care providers, whose ultimate duty is to save the patient's life, find themselves in a most awkward position when dealing with death. Faced with such a predicament, some go out of their way to delay the inevitable at all costs, while others abdicate the challenge. Failure to address the totality of the situation professionally would be most unfair to all involved. It would continue to exact an unbearable psychological and social cost from the patient, the family, and the health system. Terminal care here is a deliberate attempt to make the painful termination issues explicit and design an optimal system to resolve them professionally.

11.6. Output dimension

Care facilities (actual or virtual) will represent the output dimension of the architecture, which provides the interface between the patient/client and the provider.

Health delivery is a real-time system, where the provision of the service is contingent upon the interface between the client and the provider. The output dimension will be represented by the location of the interface where care actually occurs. This location is not limited to in-patient, hospital care. Care can occur at other locations, such as ambulatory health facilities, physicians' offices, specialized clinics, labs and diagnostic centers, nursing homes, fitness centers, and the home.

All of these facilities are included in the administration of care in the health delivery modules network. The operational framework for organizing and managing the totality of this network will constitute the basic health delivery module. The module will replicate itself in different degrees and in various regions that will be covered by Butterworth Health System.

The health delivery modules are responsible for the operation and maintenance of the facilities as well as the actual provision of patient care services. The modules will replicate the three-dimensional architecture with their own shared services units, including such services as facilities management and maintenance. However, the model for delivery of each type of care will come from the respective part of the care system.

Some prominent aspects of the health delivery module are as follows:

• The health delivery module will develop a competency in hospitality management. This competency is necessary to redesign the operation so that an order-of-magnitude change in the performance measures, especially cost of operation, can be achieved.

• The providers who are an integral part of a facility, such as operating room, general care unit, specialty care unit, and other ancillary departments, will be permanently assigned to that facility while retaining their membership in the knowledge pool.

• The current model of the “emergency room” operation will be reconceptualized and redesigned. No longer will it be allowed to act as convenient, free access to the care system. Consequently, creation of decentralized regional primary care centers will help take away the incongruent responsibilities that are currently imposed on emergency departments. Such a realignment will make sure that Emergency Department (ED) units can afford to discharge their legitimate, and highly critical, function without having to get constantly sidetracked by nonemergency referrals that come in through the ED and must be treated in such an intense setting.

• Regional primary care centers will be in charge of services that should rightfully fall into their specialized domain. The decentralized arrangements of the regional primary care centers will have the added advantage of bringing nonemergency services closer to where the patients are.

• The overall cost-effectiveness of the care system will be significantly increased by redirecting an enormous amount of expensive nonemergency services, currently seen in ED, to the regional primary care centers.

• So as not to deny access to indigent patients, the creation of the Butterworth Health Care Card for indigent patients will facilitate this rationalization of services.

Output units will be responsible for designing the interface among all the facilities and locations dealing with different levels of care in such a way that a seamless flow of patients will be ensured throughout the system.

In developing the HDS structure, two different approaches were initially considered.

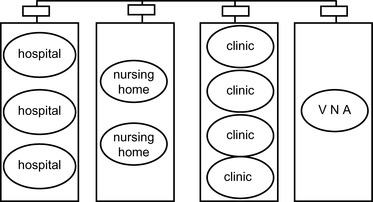

11.6.1. Alternative One: Traditional Functional Structure

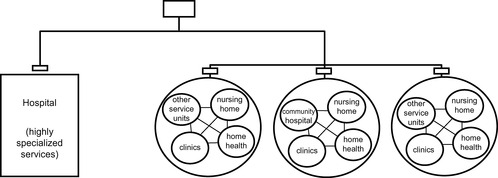

In a traditional functional structure (Figure 11.3), similar services such as hospitals, VNAs, nursing homes, and clinics, while maintaining their autonomy, will be grouped together. For example, all hospitals will report to a single group leader and will serve all communities. The same will be true for all the clinics, nursing homes, and other functional units. Each function will represent a single organization serving all of the communities.

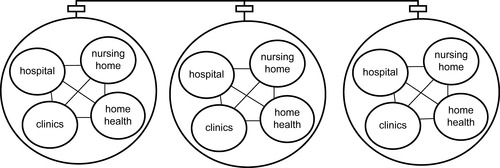

11.6.2. Alternative Two: Modular Structure

The modular structure (Figure 11.4) would be a community-centered design in which a whole array of complementary activities (hospitals, clinics, and nursing homes) is grouped together to form an integrated module under single management. This module would have a community focus, and all its units would serve a single community to ensure the kind of efficiency and self-sufficiency needed in responding, on the spot, to the whole range of needs in a specified community.

The advantage of a functional structure is that it will be easier to implement. There will be no resistance to such a design from the existing system. However, a functional design will continue to suboptimize and reinforce the existing disjointed service centers. The modular design, on the other hand, will face stronger resistance to change and will require stronger resolve to implement. But it will move the system toward a community-based health-care system that Butterworth aspires to. The modular design will produce a well-integrated and cost-efficient health system that is more compatible with requirements of preventive care, capitation, and decentralized community-centered health-care systems.

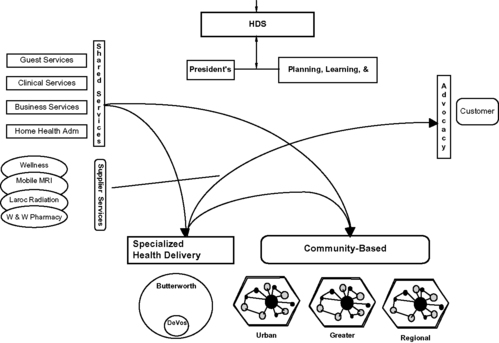

However, further iterations led to a synthesis of both alternatives (Figure 11.5). It was realized that by incorporating the advantages of both functional and modular design into a single structure, the HDS will be able to avail itself of the flexibility required to strike the right balance between the two structures rather than make an exclusive choice between the two. In the new multidimensional structure, all services that are general-purpose- and community-based can be grouped into decentralized modules capable of being duplicated in each viable community. However, those services that are highly specialized and capital intensive, requiring critical mass market, can take a centralized form serving the cases beyond the competence of the community-based modules. Thus the new design can incorporate a learning capacity that will allow the system to experiment with different ideas in different communities. Successful experiments will then be disseminated among the communities. This will provide HDS with opportunities for continuous improvement without subjecting the total system to potentially costly experiments.

11.6.3. Health Delivery System Design: The Makeup

The HDS design will integrate the advantages of both functional and modular structures into a multidimensional system. It will be made up of five interdependent components: community-based health delivery system, specialized health delivery system, shared services, patient relations, and president's office (Figure 11.6).

The existing functions of Butterworth Hospital are reassigned among three platforms. Those functions requiring development of knowledge were housed in core knowledge, those requiring design methodology were housed in care systems, and health delivery activities requiring facility and equipment were housed in HDS.

11.6.4. Community-Based Health Delivery System

The community-based HDS will be made up of modular entities offering integrated services to specific communities. It will be driven by a customer focus and be made of regionally dispersed and locally managed networks of delivery modules positioned as closely to the delivery point as possible. (There seems to be a 20-minute time limit that consumers are willing to travel for primary health care unless the area is very rural, in which case the time limit expands to 37 minutes.) Once piloted experiments justify their existence, the networks will offer a whole range of preventive, primary, viability, and terminal types of care. Geographic organization of delivery modules will have the advantage of making it easier for their outcomes to be measured separately.

A network may start as a virtual entity, but it will eventually be organized around a central physical place. The network will be flexible, fluid, and easy to link to. The intention will be to increase the opportunities for expanding and extending outpatient services and, at the same time, push the ancillary services as closely as possible to financially viable core masses of clients.

The community-based HDS will consist, initially, of three integrated modular networks: the Urban Grand Rapids community, the Greater Grand Rapids community, and the regional community. Each community module will report directly to the president of HDS. A typical network will include at least a central community hospital serving the network. The system will include the following services:

• Primary practices (physicians' offices)

• Diagnostics centers

• Rehabilitation centers

• Community clinics

• Urgent care

• Hospices

• Home nursing

• Occupational health management

Kent Community Hospital will be integrated into the Urban Grand Rapids community, Villa Elizabeth Hospital and Grand Valley Health Center will be integrated into the Greater Grand Rapids community, and United Memorial Hospital, once transferred from the specialized HDS to this dimension, will act as the core of the regional community.

HDS can extend its presence into new regions by partnering with existing providers who will have demonstrated that they have workable knowledge of, and access to, a given community. In such cases it will be the nature of the relationship with the supplier unit rather than its ownership that will be of critical importance.

HDS will take advantage of clinical information technology to link all providers in HDS and other parts of Butterworth together.

11.6.5. Specialized Health Delivery System

The specialized HDS will represent Butterworth Hospital. It will be a centralized vehicle where capital-intensive, highly specialized health-care delivery will actually take place. As such, it will concentrate on those intervention and tertiary cares that will be outside the competence and resources of the community-based HDS.

The specialized HDS will consist of two interdependent components: patient care and ancillary services. The two units will have their own heads, who will report directly to the president of HDS.

11.6.5.1. Patient care

Patient care, as the output dimension of the specialized HDS, will consist of the following health-delivery units:

• Children's care (DeVos Children's Hospital)

• Adult critical care

• General medical services

• Women's health services

• Emergency/urgent care

• Specialized outpatient care

11.6.5.2. Ancillary services

Ancillary services, as the input dimension of the specialized HDS, will provide clinical/technical support services to both patient care units as well as the units of the community-based HDS. These shared services will have to undergo periodic process redesign to remain self-sustained and competitively cost-effective. Ancillary services will consist of the following units:

• Operating room

• Rehabilitation center

• Laboratory

• Cardiology laboratory

• Radiology

• Respiratory therapy

• Pharmaceutical

• Aeromed

11.6.5.3. Patient relations

Patient relations will perform an advocacy function by representing the interests of the patients to the system. It will make sure that patients have a voice in the system and are fairly treated. The unit will act as an ombudsman to help settle grievances and compensatory claims. This will help prevent problems from growing into major litigation. Advocacy will also be responsible for providing social and financial counseling services to the patients who will need them.

Patient relations will also represent HDS to its environment. It will develop operational contacts with the corporate market access platform to receive feedback about the way HDS is perceived by its environment. This will ensure that Butterworth's policy of preserving a close community touch is enforced.

To effectively safeguard the interests of the patients and make sure they enjoy a dependable last resort to settle their grievances, it will be important that this dimension be taken seriously by all units of HDS. The realization of this market/consumer-oriented policy will require that patient relations are represented and directed by a manager who commands organization-wide respect and prestige and has direct access to the HDS president.

11.6.6. Shared Services

As an input dimension, shared services will serve and support the activities of the other units of HDS. The relationship between shared services and the user units will be that of supplier–customer.

Shared services will consist of the following five components. These services could have been assigned to the shared services platform at the corporate level. However, since they will be utilized mainly by HDS units, it was decided that their retention here will help minimize complexity and unnecessary interactions that would otherwise be unavoidable.

11.6.6.1. Hospitality and facility management

Hospitality and facility management will include all those guest services that will contribute to the hospitality aspect of an HDS. The idea is to make sure that the patient is treated like a guest at a hotel where his/her satisfaction receives the utmost priority and attention. To ensure a total hospitality approach to health-care delivery, hospitality and facility management will be in charge of all activities that will be necessary in creating a hospitable environment. These will include facility planning, construction, management and maintenance, escort and hospitality, and communications.

11.6.6.2. Clinical services

Clinical services will function as a centrally managed scheduling and deployment system that interfaces with core knowledge. Clinical services will include infection control, food and nutrition, volunteer services, laboratory, family care services, information technology, and medical services records.

11.6.6.3. Business services function

The business services function will include management consulting, materials management, plant operations, procurement, general financial services (payroll and reimbursements, patient financial services), malpractice claims, risk management, process control, environmental safety, and home health and hospice administration.

11.6.6.4. Home care management

Home care management at this dimension will only represent the management of home care that will actually take place on a widely dispersed basis throughout the community health modules. It will take advantage of the large economies of scale associated with such a large core mass. Moreover, HDS may partner with other hospitals to manage these services for them. Home care management will therefore consist of general management, oversight, scheduling, standardization, and accreditation.

11.6.6.5. Occupational care management

Like home care management, occupational care management will represent only the management of occupational care that will take place throughout the HDS's geographical regions. The service will be provided to corporate customers interested in outsourcing to HDS their health-care needs, as well as other health-related issues of their employees, such as workers' compensation. The economies of scale associated with such a potentially large volume of widely dispersed services warrant centralized management and oversight.

11.7. Core knowledge

Core knowledge is one of the two components of the input dimension of the architecture. Core knowledge is responsible for ensuring the availability of the appropriate service scope and number of providers to meet the whole spectrum of health-related care in its regions.

Core knowledge will be the system's center of expertise. It hosts and develops the provider resource of the system and helps the care system disseminate the state-of-the-art knowledge throughout the system. It will represent Butterworth's core competencies in medical practice.

Core knowledge will consist of the following health-care providers:

• Medical staff (primarily consisting of physicians as independent contractors)

• Advanced practice providers

• Nurses

• Technical health workers and other professionals/clinicians

• Other professionals/technicians

The core knowledge network will be designed to accommodate a broad range of relationships. It will define and develop the structure for various types and degrees of membership in the system and the necessary operating procedures for members to interact.

Without an infrastructure for collaborative effort, the scarce provider resource will tend to be defused and wasted. The supportive organization should therefore be flexible enough to enhance maintenance and utilization of provider resources. This would ideally require each member of the provider system to be a high-level learner/educator, practitioner, and a leader of systems development. The absence of any one of these critical and interrelated aspects will undermine the others and eventually compromise the capacity of Butterworth to perform as a fully functioning system. Sustaining such a balanced state of readiness will ensure the comprehensiveness and the flexibility of the system's response to emerging problems and opportunities and at the same time encourage professional pursuits of purposeful networking and results-oriented collaborative initiatives.

To enjoy constant access to a rich resource of expertise representing state-of-the-art health care, the organizational context of core knowledge will constantly welcome maximum flexibility for innovative collaboration and will remain open to existing and emerging inputs of relevance both from within and outside the system.

Membership in the core knowledge system will therefore take a wide variety of forms functioning at multiple levels of involvement. The types of membership will be both full- and part-time and will include the following:

• Independent practitioners (retainer-based)

• Associates (referral-based)

• Partners

• Nonaffiliates

To assure openness to external inputs of needed competence, the core knowledge system will operate as a confederation. Members of the confederation can be individuals as well as groups of providers. The status of the members of the core knowledge confederation may take the following form:

• Integrated: full-time members of Butterworth Health System

• Part-time: individuals with limited and predefined contributors

• Strategic alliance: organization-based partners operating within an agreed upon framework

Core knowledge members may choose to assume or relinquish different degrees of autonomy in working with Butterworth Health System. The nature and terms of this voluntary association define the areas in which the parties will choose to compete, collaborate, or cooperate. Thus, core knowledge members and Butterworth are codependent parties; their commitment to, and freedom from, each other is mutually reciprocal.

Creation of mutual trust between the Butterworth Health System and the core knowledge dimension will be the keystone to the ultimate success of the system. They should represent a united front to competition. A prerequisite to this loyalty-based success will be an environment that minimizes and dissolves conflict, whether real or perceived. Such an environment will require the following:

• All the members of core knowledge, regardless of their status, will have an equal voice within their panel, in the management of the group.

• All the members of core knowledge, regardless of their status, will have equal access to the shared services, such as billing, which will be provided to them on a marginal cost basis.

• An explicit internal system of conflict resolution will prevent, minimize, and dissolve potential conflicts before they are polarized.

The architecture of the core knowledge dimension will be a clone of the health system. It therefore has the same input, output, and market dimensions. The output dimension defines the types of contributions of the integrated, part-time, and strategic partners of core knowledge to the care system and health delivery modules. The market dimension defines the access mechanism by which core knowledge services are deployed. The input dimension represents those support services that are core-knowledge-specific and cannot, by definition, be provided by the system's shared services. The input dimension will provide its services on a marginal cost basis to its users.

To bring about a productive climate for continuous innovation and improvement of health-care delivery, the professional contributors will have to develop an additional vital dimension: the ability and desire for organization building. Traditionally, the complementary responsibility for designing and managing the contextual environment of HDS has been uncoupled and transferred to administrators who are removed from the actual provision of clinical services. Because of this separation, substantial amounts of energy have been wasted in settling the unnecessary incompatibilities in the structure, function, and process of health-care delivery.

The only way to dissolve the paralyzing effects of the structural conflict is to add the missing dimension of care management leadership to the health-related expertise of the clinical providers. Equipped with leadership and design capability, health-care professionals can properly influence and/or help design the necessary interface between the context and the mode of delivery. The dual capacity would not only remove bureaucratic compartmentalization, but would enhance the effectiveness of care services by tapping the potentials for experimenting with alternative ways of teaming and complementary relations.

Core knowledge will be responsible for the generation and distribution of the knowledge, deployment of expertise, and exercise of leadership. These three functions are described in the following list:

1. Generation and dissemination of knowledge (learner/educators). The provider system will be responsible for continuous learning and self-renewal of its members. The members will be expected to represent the health profession's state-of-the-art expertise. They will conduct most of this high-level self-education through teaching themselves as well as participating in applied research activities. They will be learning by teaching and learning while earning.

A portion of the provider resource may be engaged in ongoing academic pursuits that are either an integral part of medical schools or activities complementing such faculty engagements.

Members of the provider system may also engage in educating those who have a stake in health-related activities. Those who will be taught will include peers, students, interns, consumers, and the public at large.

The core knowledge dimension, however, will be responsible for creating interfaces and developing active associations with other sources of research and learning, such as universities, research institutions, medical and paramedical education centers, and technological development organizations.

2. Deployment (practice). As pointed out earlier, core knowledge is responsible for ensuring the adequate availability of and the appropriate scope of and level of providers required to meet the whole spectrum of health-related care in all its regions at all times.

Members of the provider system, operating within the framework and protocols set by the care system, will contribute their knowledge and expertise by participating in different long- or short-term projects/programs that are created and terminated within the care system or the health delivery modules. The practice will take place in inpatient care (hospitals), clinics, labs, local health centers, wellness centers, homes, and long-term-care institutions. Members of core knowledge can choose to function on a permanent or temporary basis on different programs and projects without losing their full-fledged membership, and the privileges that come with it, in the core knowledge group. Each member can work in multiple programs/projects at the same time.

The power of multidimensional architecture, as developed in this design, is that it intentionally avoids the danger of tying the fate of the providers and the programs inseparably together. Once created, there is a tendency for the programs and projects to become a permanent feature of the organizational landscape. Left to their own devices, they develop a life and a mind of their own. Their fate is sealed, however, when their personnel are permanently assigned to them. The seed of the problem is in identifying the product with the provider, as is done in a divisional structure commonly used in academic and industrial settings wherein a program or product, once initiated, can never be discontinued. As long as the termination of a program or project threatens one's job and all the hard-won advantages associated with it, it is only natural that the job holder, whether a manager or a simple worker, does his/her utmost to lengthen the life of the project at all costs. This explains the inner rationality of the seemingly irrational resistance and obsolete relics that somehow manage to survive in corporate life.

Dissolving the problem will require that the life of the programs and projects be uncoupled from the people who are assigned to them. One of the advantages of having a core knowledge dimension in the systems architecture is that it will serve as the permanent home base for the professional resources of Butterworth. Any other relationship and assignment will, by definition, be considered as contingent and temporary no matter how long it is expected to last. The permanence of the core knowledge home base, requiring continuous reassessment and renewal, and the impermanence of programs and projects, allowing continuous innovation and adaptation, remove the obstinate conditions that lead to inflated bureaucracies and entrenched resistance to change.

3. Leadership. Leadership in this context is defined as the ability to influence those over whom one has no authority. Competency in medical and health technologies, although a crucial necessity, does not by itself guarantee the success of a health-care system. To be sufficiently effective, every professional member of the system should be an influential leader as well. Thus every provider should have the desire and the ability to positively impact the context, structure, and process of Butterworth. To achieve this vital task requires knowledge workers who (1) internally, seek to participate in the design and management of care modules and procedures for doing more with less and (2) externally, proactively influence the contextual environment of Butterworth to remove the obstructions and expand its potentials for doing more and better. Butterworth simply cannot afford the conventional, and dysfunctional, division of labor between clinical and management-related functions.

In the final analysis, a good provider, therefore, is a good learner/educator, a good practitioner, and a good leader. The success of Butterworth and its providers, and by the same token any health-care system, will ultimately depend on whether the members of the provider community have achieved this multifunctionality in addition to being competent practitioners.

Building multifunctionality into the provider community will convert obstruction into opportunities and replace aggregates with systems. Thus individual providers will become purposeful members of a highly interdependent system that will make a difference. They will effectively use their multiple competencies in managing upward and influencing other parts of and stakeholders in the health-care system over whom they do not have direct control but on whom the success of their professional effort will depend.

The multifunctionality will also give providers the capability and the possibility of designing and managing their practice in terms of affordable and user-friendly packages and programs that are both accessible and relevant to the consumers. They will cooperate with the care system in the development and continuous improvement of generic models, protocols, and procedures needed to manage the different aspects of HDS.

While the core knowledge group is responsible for medical research and education, it will replicate the three-dimensional scheme to create its own special shared services. Shared services in this context will include physician's office management and provider recruiting and credentialing.

11.8. Shared services

Shared services is the other component of the input dimension of the architecture. It will be the provider of specific services required for the proper functioning of the system as a whole. To ensure its proper functioning, shared services will be designed with close attention to the issues surrounding centralization and decentralization, separation of service from control, and customer orientation.

11.8.1. Need for Centralization

Centralization will be avoided unless one or all of the following situations weigh overwhelmingly against decentralization of a particular service.

11.8.1.1. Uniformity

The aspects of the system that will be centralized are those that are common to all or some of the parts of Butterworth and cannot be left decentralized without rendering serious damage to the proper functioning of the system. In areas such as measurement systems and communications, where common language and coordination are of major importance, uniformity will serve as the criterion for centralization.

11.8.1.2. Technological imperatives

Certain technologies, which, because of their nature, are deemed indivisible and therefore require a holistic design, can be centralized. For example, the effectiveness of a comprehensive information system is in its holism, consistency, real-time access, and proper networking to transfer information as needed to different users. Development of such a system requires cooperation and coordination among all the actors in the system.

11.8.1.3. Economy of scale

Although economy of scale is generally considered an important factor in the creation of shared services, the trade-offs between centralization and decentralization of each function should be made explicit to prove that the benefits significantly outweigh the disadvantages before it is moved to shared services. In this case, it is expected that a service, once centralized, will either generate significant savings for the system as a whole or help some of the units that otherwise would not be able to afford the service on their own.

Management may feel that a certain level of specific activities will be critical for future success and therefore decide to centralize, develop, and specialize them. It is management's prerogative to identify the services that should fall under this category either as optional or mandatory. Where only one unit/customer is involved, it is best to decentralize the relevant service.

Whatever the justification of the services shared, the unit will have to become the state-of-the-art and cost-effective provider of choice.

11.8.2. Control Versus Service

The combination of a control function with a service function is the most obstructive element to the functioning of shared services. It undermines both the effectiveness of the services and the legitimacy of the controls. To protect themselves against the creeping hegemony of service providers and the obvious risks involved in relying on control-driven services, the operating units resort to duplicating the support services that could otherwise be easily shared and effectively utilized. Rampant and excessive duplications of services leading to paralyzing bureaucracy and unnecessary redundancy are symptomatic of the natural reaction of operating units to service functions developing such dual personalities. On the other hand, disguising a legitimate and necessary control function under the pretext of a service function transforms the nature of control from a learning mechanism to a defensive and apologetic act.

Extra care should be taken to make sure that none of the functions of the shared services, as is the usual tendency, undergo a character change and assume control properties. Under the pretext of a need for consistency and uniformity, there is a natural tendency to let the service provider perform the necessary monitoring and auditing function. This has always proved to be misguided. The providers cannot help falling into the slippery slope of wanting, increasingly, to assume a control function. This obviously would scare away the users who did not expect to find a new boss in the guise of a server.

While shared services will provide the customers with requested services (such as information, benefits, payroll, and billing) in accordance with the criteria and protocols set by the Planning, Learning, and Guidance (PLG) System, the PLG System will be in charge of setting the policies and the criteria governing these services, as well as conducting the necessary monitoring and enforcing functions to ensure proper implementation of those policies.

11.8.3. Customer Orientation

While superior–subordinate relationships have traditionally been taken as the only building block for the exercise of organizational authority, the supplier–customer relationship introduces a new source of influence into the organizational equation. With the supplier–customer relationship, which emerges only in an internal market environment, the helpless recipient becomes a real customer. Armed with purchasing power, the customer becomes an empowered actor with the ability to influence and interact with his/her supplier in such a way that both parties together can now define the type, cost, time, and quality of the services rendered.

Creation of an internal market mechanism, and thus a supplier–customer relationship, is contingent upon transforming the shared services into a performance center. Performance centers, unlike overhead centers, do not receive a fixed budget allocated from the top. They have working capital with a variable operating budget. In this model, expenses are proportional to the income generated by the level of services rendered and revenues received in their exchange.

These two pairs of horizontal and vertical relationships are complementary, synergizing one another. Whereas superior–subordinate defines the formal authority, dealing with hiring, firing, and promotion, a supplier– customer relationship creates a new source of influence that tries to rationalize demand.

In the absence of an internal market environment, there will be no built-in mechanism to rationalize demand. An agreeable service provider with a third-party payer creates and fuels an insatiable demand. A disagreeable service provider, on the other hand, would trigger a proliferation of duplications of the same services by the potential customers. The result would be an explosion of overhead expenses in the context of an essentially cost plus operation. The trend would be irrational and the corrective interventions would prove ad hoc and ineffective, at best.

On the basis of these criteria and considerations, the composition of shared services is as follows.

11.8.3.1. Information system group

• Data management (clinical data, financial data, and human resource data)

• Information technology

• Systems analysis

11.8.3.2. Management institute (education services)

Implementation of the proposed design will require institutionalization of a whole new set of management capabilities, such as crisis management, conflict resolution, and management of the decision system, learning system, early warning system, measurement system, and quality. The services of the Management Institute will interface with external centers of relevant expertise and disseminate the required competencies throughout the Butterworth Health System, especially the executive office and core knowledge groups.

11.8.3.3. Human resource management

• Payroll

• Benefit administration

• Compensation management

• Recruitment (implementation only)

11.8.3.4. Financial systems

• Budget and cash flow management

• Accounting

• Billing

• Collections

11.8.3.5. Medical records management

• Release of information

• Consistency standards for records

11.8.3.6. Communications

• Public relations

• Media interface

• Audio/visual equipment and management

• Corporate branding

• Advertising

11.8.3.7. Materials management

• Purchasing

11.9. Health delivery system, core knowledge, and care system interactions

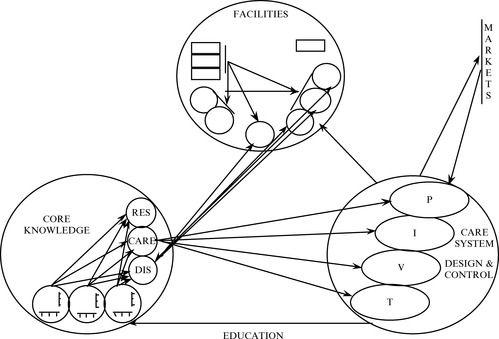

The health-care system is a unified process. It has, however, three manifestations representing three aspects of the same thing: generation and dissemination of health-care knowledge, design of health-care products, and practice of health care. Correspondingly, the architecture provides three interrelated platforms to make sure these three aspects are considered prime functions requiring equal attention. To safeguard the integrity of the health-care process, it is therefore critical that the integrative agent of these seemingly different functions be clearly identified (see Figure 11.7).

The integrity of the process of health-care delivery, more than anything else, will be the property on which the system will ultimately stand or fall. This will require that the three activities of generation and dissemination of health-care knowledge, design of health-care products, and practice of health care, while receiving equal attention, be integrated. The importance of the three activities is such that the proposed systems architecture assigned each one of these activities to a different platform under a separate manager.

On the other hand, these three activities are so interrelated that their integration will be a prime concern. This seems contradictory to the above statement that explicitly assigns the three activities to three separate platforms. The question, therefore, is how the integration of the three platforms is supposed to happen. This brings us back to the core idea of the architecture. A key assumption of this design is that the only way to ensure the integration of the system would be for the knowledge worker to become the integrator.

This means that the integration of the three activities of learning, designing, and practicing health care will be realized by the fact that the designer, the educator, and the practitioner would be one and the same. To preserve the wholeness of the process of providing care, each professional contributor, whether a doctor, nurse, or technician, will be engaged in the three distinct and yet interrelated roles that will feed on and contribute to each other's strength. When in core knowledge, the same provider will help generate and disseminate knowledge by participating in learning cells as a learner/researcher/educator. When in care systems, the same provider will help operationalize his/her knowledge by participating in design cells as a designer/evaluator. When in HDS, the same provider will help utilize new knowledge by participating in practice cells as an implementer/practitioner.

Engagement and ownership of each one of the three complementary and mutually reinforcing roles will prepare, empower, and motivate the provider to succeed in dealing with the other two. Thus a designer/evaluator and at the same time the practitioner of particular products and services will always be most qualified and ready to teach them; a learner/researcher/educator and at the same time the practitioner of particular products and services will always be most qualified and ready to design them; and, finally, a designer/evaluator and at the same time the learner/researcher/educator of particular products and services will always be most qualified and ready to administer them.

In all three contexts, the integrative agent is the doer who has first-hand experience with the problems. Thus the system will become self-correcting, self-educating, and self-integrating. The design will allow the professionals to manage upward and create a “low-archical” approach intimately suited to the idiosyncrasies of a multi-minded and professionally driven organization. Thus, the success of the system will depend on the ability and willingness of the professionals in acting out, depending on the context, all the different roles of learner, educator, designer, and practitioner interchangeably. Although this seems to be against the implicit assumptions of health care, it is perfectly compatible with human nature. In real life, individuals perform many different roles. For example, one plays, quite naturally and almost simultaneously, the roles of parent, professional, friend, boss, and subordinate in different contexts without difficulty. As a matter of fact, this happens to be one of the characteristics that distinguishes humans from other species and constitutes the keystone of social existence.

The composite performance profile of each professional will therefore reflect the three aspects of his/her role as an educator, a designer, and a practitioner. The profile will show the value of the individual to the organization based on the quality and diversity of the roles he/she will be called upon to play in the different contexts of the value chain. The higher the competence, the greater the demand; the greater the demand, the higher the value. One point, however, needs to be underscored here: the design will not encourage, but it will certainly respect, the personal preference of those professionals who, for whatever reasons, might elect not to engage in multiple roles.

In the trio of core knowledge, care system, and delivery system, core knowledge will serve as the home base for the system's physicians, nurses, technicians, and other health-based professionals. This will make it possible for the knowledge worker to accept different roles with different durations in all three platforms. When at core knowledge, it will be the providers themselves who will help perform the stewardship function of the human assets. They will be engaged in learning from and teaching each other to make sure that the health-care competency of Butterworth represents the cutting edge of the health-care profession at all times. They will constantly monitor the direction and state of the science and practice of health care. They will make sure that the entire professional competence of the system is in a state of readiness to respond rapidly, effectively, and adequately to the changing and growing requirements of the market.

While care systems will be responsible for designing the process and packaging health-care products and services, as well as monitoring and ensuring the quality of their deployment, HDS will be where health care will actually happen. HDS will own the capital-intensive and health-related physical assets and will be responsible for their effective utilization in providing the care deliverables.

The three-dimensionality should not be mistaken for the conventional concept of the division of labor and the three-boss system. The three platforms manage the three different aspects of the system, each with a clear-cut accountability in the process. Their relationships will be governed by all three aspects of authority: legal, knowledge, and financial. Across the three contexts, knowledge is the common denominator and therefore will work as the integrative agent. The relationship of the members and their manager in the core knowledge group is boss–subordinate (legal), while in the context of the care system and delivery system the relationship is customer–provider. The successful operation of the three units will therefore require that the creation of a throughput and measurement system with variable budgeting be an integral part of this design.