Sense and Respond

Abstract

An enterprise must, not only, be timely in response to anticipated events, but it must be sensitive and responsive to changes in technology, advances in methods, strategic moves by competitors, market changes, availability of key resources, as well as consequences of social, political, and economic changes. This chapter discusses the capture of events and circumstances, the tracking of responses, and the escalation of responses and business planning. This is supported by discussions of the strategic planning framework, business transformation management, product life-cycle management, supporting organization units, and an IT sense and respond infrastructure.

Keywords

Sense and respond directory; Analytics; Enterprise agility; Levels of agility; Planning horizons; Capability unit management; Line of business management; Virtual enterprise; Transformation management; Product life-cycle management; Value chain; Value chain stages

Business and technology continue to change at an accelerating pace. Companies must innovate to improve their products and processes. Things are happening outside the enterprise that represent potential threats and opportunities. The market is changing, new products are being introduced, economic conditions are changing, international situations are affecting trade, competitors are pursuing new strategies, technology is changing, creating new markets and opportunities for improved efficiency, quality, or timeliness.

In today's world, an enterprise must be more sensitive to emerging challenges and opportunities and be prepared to adapt more quickly and significantly than in the past. Generally, we expect leaders to watch for changes that might affect them, or we expect executives to discover what is happing in the marketplace and the industry and deal with it in strategic planning. The agile enterprise must be better than that.

There are events, trends, and patterns of behavior in the marketplace or the enterprise ecosystem where the response should be to change the business. Sometimes the needed change can be addressed primarily by a particular organization unit and can be resolved quite quickly. Other responses should be broader in scope, particularly where the agile enterprise has shared capabilities that may impact multiple value streams. Still other threats or opportunities may require substantial or pervasive changes that must be defined and coordinated across the organization. Occasionally, there will be a potential opportunity to drive a radical industry change that could dramatically change the marketplace for significant competitive advantage (or disadvantage).

In this chapter, we will consider how the agile enterprise senses and responds to change. We will begin by considering the drivers of change and how we manage different levels of change. Then we will discuss transformation management using a value delivery management (VDM) model to define the future business design and phases of transformation. Next we consider the management of change through an example product life-cycle. Finally, we discuss enterprise-level business change support and sense and respond infrastructure requirements.

Drivers of Business Change

Occasionally the need for business change may be triggered by an event, but more often, the recognition of opportunity comes from realization of the impact of trends or relationships that create a synergy between emerging technology, declining costs, and market trends or emerging markets that may also be tapped by innovation. Some of these changes drive continuous improvement, and others drive significant changes in products or the industry.

This section will focus on the drivers of change to the business. We will describe these as relevant circumstances. These may also be associated with events, but circumstances more often involve a number of factors, trends, or expectations from which we may infer a business threat or opportunity.

So as we observe the development of new products in an industry, there are precipitating events, actions, investments, features, and market growth. Unfortunately, by the time there is a product and a market, the observing enterprise is already behind the competition. There is usually opportunity to become aware of a new technology, a market change, or a new business discipline as the basis of a competitive threat. For example, work on a new technical standard will typically begin years before implementations of the standard will come to market. The initiation of work on a standard is evidence of a demand that will eventually have consequential effects.

We should be aware of the evolving circumstances that drive the development of new products or services and decide when the potential customer demand (or other stakeholder) reaches a threshold that requires action to mitigate a threat or lead in the pursuit of the opportunity. This requires both broad industry knowledge and an understanding of the potential marketplace. In some cases, a radical change will represent a major opportunity (and risk) and will involve synergy with business partners, potentially including another industry.

A capability oriented architecture brings economy of scale that enables development of expertise in each capability and the circumstances affecting advances in that capability. This expertise should be encouraged and leveraged as a source of awareness and insights from outside the enterprise.

The enterprise must leverage the insights of the internal experts scattered across the organization. These are not only experts in their particular area of the business, but they live in the real world where, collectively, they have a diverse view of the enterprise stakeholders and potential markets, and, hopefully, some of them have an opportunity to attend conferences or standards meetings to have contact with industry experts.

The interest groups discussed for knowledge management in Chapter 6 are key to recognition of potential synergy of multiple trends and emerging technologies to form a new business opportunity. Participants in these groups should understand that such insights and innovations are part of their jobs. They are sources, and potential catalysts of new business visions.

This decentralized knowledge acquisition and innovation deserves some coordination and collaboration. A current enterprise VDM model will provide a context for this coordination and collaboration. Enterprise-level support is discussed in a later section.

Some changes will be incremental improvements that may support or improve market share. At the other extreme, some changes could dramatically change the market, the industry, and the competitive landscape.

In the following sections, we will consider sources of knowledge and insights about relevant circumstances, evaluation of the scope of impact of an observation or implication, and the role of executive staff organizations in providing business change support and leadership.

Sources of Knowledge

Underlying a new product may be an event such as the realization of an innovation or invention. While the invention is important, the development of a product and a market takes time and additional creativity. We may see the announcement of the new product as an event, but that is a milestone in a process. The success of the product will then depend on the readiness or development of the market—the development of demand and sales.

Significant circumstances seldom occur in a single event. Development of new technology and growth of a market may take years to develop. Below are a number sources of knowledge that can provide insight on things to come. Various employees should have access to these sources depending on their areas of expertise and roles in the business.

Public News Media

Employees at all levels should be aware of world events and changes in social, economic, and political circumstances. These affect the demand for products, the cost and availability of resources, the availability of funding for the enterprise and customers, and other factors.

Market Segment Industry Associations

Market segment industry associations are important sources of information on problems and concerns of customers that may suggest product improvements or problems to be addressed with new products or services. They may also suggest opportunities for synergy between industries.

Professional and Standards Organizations

Professional and standards organizations engage people who are aware of new ideas in their professions and they participate in the development of standards because those standards are relevant to their employers’ capabilities or plans.

Industry Literature

Industry literature is a source of advertising by vendors that have something new to offer. The literature also includes articles on new approaches by members of the industry.

Industry Conferences

Conferences are forums for people to highlight their accomplishments and new ideas. In addition to listening to presentations, conferences provide the opportunity to have face-to-face contact where more detailed information may be revealed in personal conversations.

Competitors’ Products

Competitors’ products reveal new designs and features for potential competitive advantage, and they may also suggest new production techniques.

Government Regulations

Actions on development of new government regulations are good indicators of public concerns affecting business operations or products. These may have significant effects on current products or processes, or on the development of new products or services.

Analytics

Analytics applications examine large volumes of data of various forms to discover events, trends, or relationships. In this context, there may be opportunities to discover new markets developed by competitor products or pricing, but it should be possible to anticipate these developments before they occur. The circumstances in which new approaches are born usually exist months if not years before they appear in the marketplace. Nevertheless, analytics may help recognize potential markets or measure the size of existing or emerging markets, to establish when a market is ready for a new product or service, or which market segment may be the best target.

However, analytics requires focus. The computer cannot decide what is worthy of analysis, rather, leaders and analytics experts must consider the various sources of data that may be available and the particular entities, variables, and relationships that are important for identification of threats and opportunities. Buying habits of existing customers may also reveal opportunities. Note that a trend or change in a variable may be more important than its current value.

Collaboration

Collaboration of employees with other employees with related interests as well as with outside professionals is a key source of new ideas and refinement of possibilities. The formation of internal interest groups for collaboration is discussed in Chapter 6. Social networking such as LinkedIn provides the opportunities to collaborate (or observe collaborations) among professionals with similar interests. Members of an interest group can pool their knowledge and insights to innovate or predict potential products or services that could represent a threat or opportunity to the business. An interest group may also help determine how analytics can help determine relevant markets and the current or future viability of a product or service.

Employees throughout the enterprise should be encouraged to develop ideas for improvements of capabilities and products. Involvement with external sources of knowledge along with participation in internal interest group collaborations should cultivate many ideas. Interest group collaborations also should help select and refine ideas for further action.

With individual employees taking initiative and participating in interest group discussions, there will likely be some people looking at the same issues. There is a need for Sense and Respond Directory to capture and record the observations and ideas to encourage coordination and collaboration, and to drive input to persons or processes that should act on the information. This is discussed more, later.

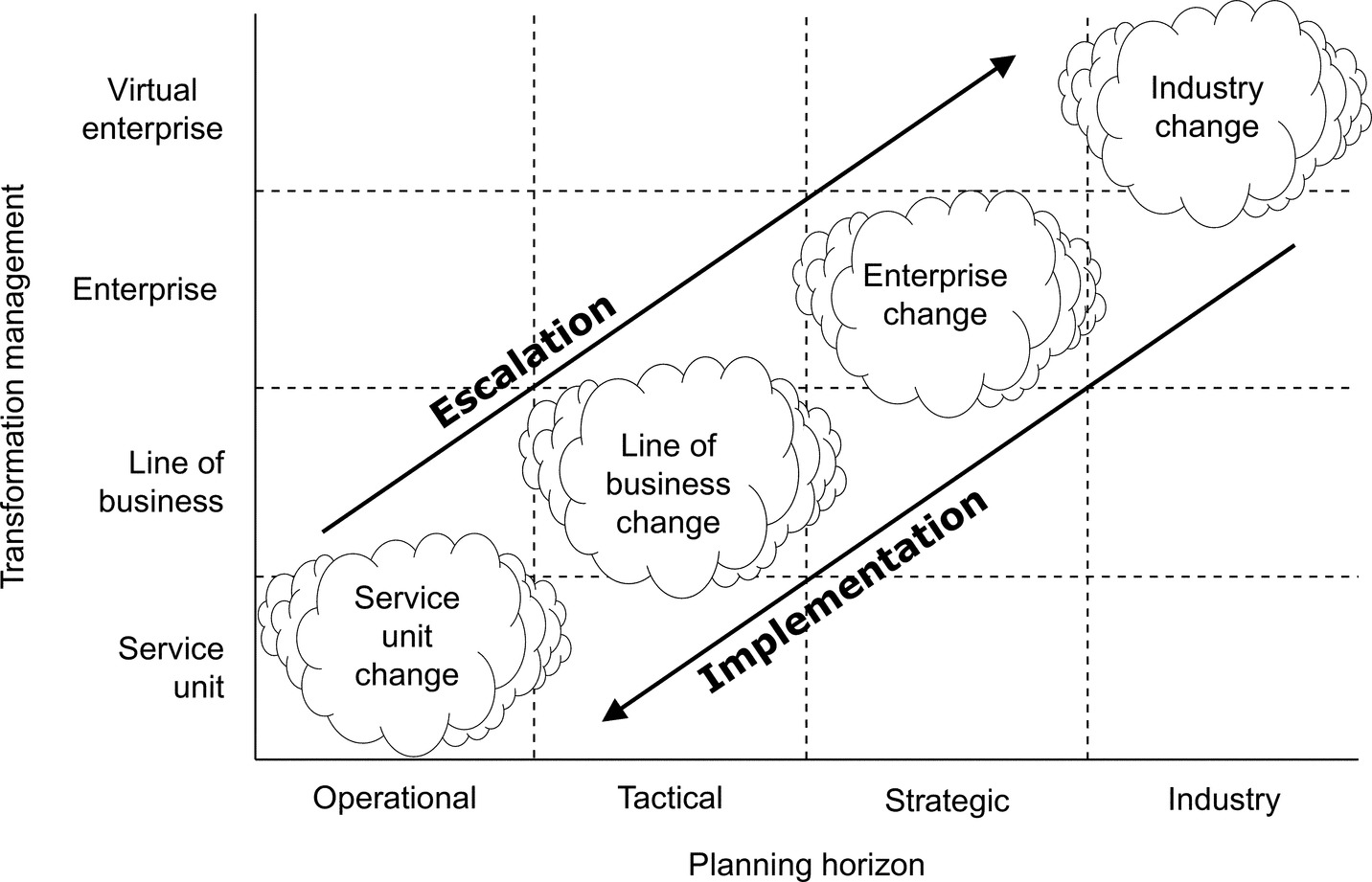

Scope of Change

Fig. 9.1 depicts a business change framework. This aligns the scope of a change with organizational levels for evaluation and further development. The planning horizon indicates the general magnitude of the undertaking and the duration of the effort. The organizational scope describes the level and number of organizations involved and thus the level of collaboration and coordination required. We will briefly describe the planning horizons and then describe the levels of organization and their involvement in the implementations.

Planning Horizon

Here we are concerned with the significance of the undertaking and thus the cost, risk, and duration of the transformation. Potential changes may be recognized at the operational level but moved up to tactical or strategic level as the scope of impact expands.

Capability units and value streams clarify responsibility for many focused business changes. VDM clarifies the potential impact and requirements for collaboration and coordination as well as a shared business design of the future state. Tactical, strategic, and industry transformations require development of a future state VDM model.

In the following sections, we consider the four planning horizons: operational, tactical, strategic, and industry horizons in the above framework.

Operational Changes

An operational change is relatively narrow in scope as improvement to a capability unit or capability unit group, it is focused primarily on incremental improvement, and it has little if any impact on the consumers of its service(s) or the services that it uses. An operational horizon change would typically be implemented within a year but may be a bit longer if there is coordination required with other capability units.

Tactical Changes

Tactical changes have broader impact, generally focused on a value stream or line of business (LOB), and may require some adjustments to other value streams or lines of business as a result of changes to shared capability units. Development of a value stream for a new product as well as a significant change to an existing product for a new market would be tactical. Changes to multiple value streams within the same LOB may still be considered to be tactical except that it is likely there will be more impact on other lines of business through changes to shared services.

These changes rely on VDM models to ensure proper coordination and enterprise optimum impact on values of affected value streams. The tactical horizon is more likely 2–4 years since it will likely involve more analysis, design, and coordination of changes in multiple capabilities and multiple value streams, and, possibly, multiple lines of business.

Strategic Changes

Strategic changes are still broader in scope affecting multiple lines of business including some shared capability units. This would include merger, acquisition, divestiture, outsourcing, and changes to administrative support services. These changes require extensive use of VDM modeling for validation of strategy, assessment of impact, and specification of the to-be business design. Introduction of new information technology would also be managed at this level if it has an impact on multiple LOB operations, for example, new personal devices (smart phones or tablets), or use of cloud computing could require significant modifications to applications and personnel training. The strategic horizon could be 4 years or more, involve multiple lines of business, and potentially impact suppliers, business partners, and customers.

Industry Changes

Industry changes involve substantial departure from an established business model to effect an industry change of direction with new or significantly changed products and services for a new market.

This includes disruptive innovation as defined by Christensen (2016), where products capture a new, mass market that will respond to lower cost, less sophisticated products. The goal is to address a new, larger market that accepts neither the cost nor the need for complexity of competitor products. Cloud computing is a disruptive change that has drawn in a larger, less sophisticated market, and is now starting to erode the business of the traditional data processing center. The leader in industry change has the potential to capture a large share of the new market before competitors can respond and thus set the standards and build on the core business over time.

Levels of Response

Based on these planning horizons, we now consider how these relate to the levels of transformation management, the vertical scale of Fig. 9.1. Essentially, we start with the assumption that management of a change is the responsibility of the manager of the organizational unit affected. This may change as the nature of the change and the scope of its impact evolve.

VDM and the capability-based architecture (CBA) enable decentralized innovation by enabling employees and unit managers to see the big picture and understand how their ideas may impact the rest of the business. Employees at any level may become aware of opportunities or relevant changes in the business ecosystem. These may be topics of discussion in interest groups. The management chain of leading participants should ensure that proposals are brought to the attention of appropriate transformation leaders. Management controls, business processes that initiate change, and capability unit manager incentives must be appropriately applied to achieve a balance between local initiative and enterprise optimization.

A VDM model for the current business provides a context for consideration of the effects of a potential change. This helps determine the organizations and levels of management that may need to be involved in consideration of a change, it provides insight on the impact of the change on value contributions and their effects on value streams, and it provides the basis for determining the enterprise-level optimum effect that may involve trade-offs.

In addition to the organizational scope of a change, there may be funding thresholds that require that a change be proposed to a higher level of management for approval of funding.

As the total transformation becomes clear, requirements on lines of business and the individual capability units will become clear, and responsibility for implementation of specific components may be delegated back to the LOB and capability unit organizations consistent with the VDM model and a phased implementation.

Capability Unit Management

The lowest level of transformation management is the capability unit. Some changes have an effect specifically on the operating activities of a particular capability unit. Resolution of these circumstances can be implemented immediately by the capability unit manager unless they require substantial investment or will adversely affect service cost, quality, or timeliness. In a CBA, the approach to implementation of service operations is internal to the capability unit, as long as it does not adversely affect service users or services used.

If a capability unit manager implements changes that improve the cost, quality, or timeliness of its operations, it must remain compliant with its interface specifications and level of service agreements of the capability unit. Some changes to interfaces and performance may be acceptable if the related capability units concur, particularly if there is off-setting value, otherwise pursuit of the changes may need to be escalated to a level appropriate to the scope of impact of the change. Shared services will have multiple recipients of their services to reconcile. Collaboration is required with related capability units to ensure continued compatibility and compliance with service level agreements. Services that are unique to a value stream—typically those that define the high-level activities—will only be concerned with the needs of the particular value stream.

For example, plans for transformation of a capability implementation may start at the capability unit level, but if the change has a functional effect on consumers of the service or services it engages, then there are broader implications to consider. This may still be resolved at the capability unit level by collaboration with the affected recipients and providers. However, if there are many other organizations, or if the change suggests a change to the corporate VDM model, then there may be cause to raise transformation to a higher level of management. The same applies to expanding scope of changes at the LOB level and the enterprise-level. Furthermore, if the planning horizon is longer, management at a higher level may be appropriate since other initiatives and considerations may come into play.

Incremental Change

Generally, changes managed by a capability unit will be incremental. This may include improvements of cost or quality or one of the following.

Regulatory compliance. Compliance with regulations may only require changes to the capability unit. They may have some effect on users of a service, but that will not remove the need to comply. Collaboration may reveal ways to comply without undesirable side effects.

Information technology. Information technology could be applied for automation, improved access to information, technology modernization, or better communication and coordination.

Production technology. Production might be improved with new or better tools or machines and potentially by changes in materials or production scheduling; however, consideration must be given to adverse effects on value contributions.

Business process. Process improvements might save labor, material or reduce scrap or defects.

Product. Product changes might improve manufacturability or maintainability or improve product appeal with new features or appearance. However, for a shared service, potential effects on other products must be considered.

Propagation of Change

If changes to internal operations adversely affect the cost, quality, or timeliness of the service for some users, the capability unit manager will need to negotiate with service users to justify the change or demonstrate to enterprise leaders that there is a net gain to the enterprise. Changes that do not affect the interfaces and do not increase cost or degrade the level of service should not be a concern to service users or providers.

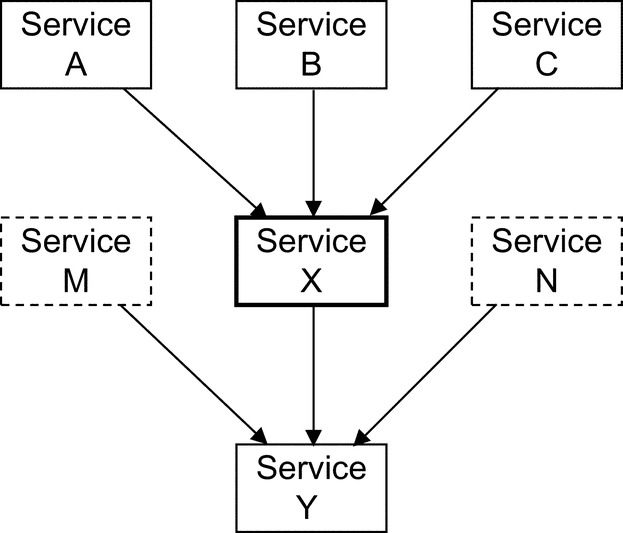

In some cases, there may be a need to change the capability unit interface, and this will require other units to make complementary changes. Fig. 9.2 depicts relationships between service users and service providers. Capability unit X is both a user of capability unit Y and a provider to capability units A, B, and C. A change to the service interface of capability unit X may require changes to all the users of capability unit X, here represented by capability units A, B, and C. If a change impacts the value contributions of capability unit X, it affects the competitive position of the value streams served by capability units A, B, and C, because A, B, and C must bear the cost and depend on the results of capability unit X in the delivery of their services.

Consequently, the solution should be the result of collaboration between the capability unit manager of capability unit X and the managers of the user capability units A, B, and C unless the changes also impact the users of capability units A, B, and C.

Note that enterprise governance should require that changes to capability unit interfaces be approved at an enterprise-level to ensure that the solution is optimal for the enterprise, particularly for future needs that might not be represented by current service users.

A capability unit may require changes to a service it uses. In the diagram, capability unit X may need changes to capability unit Y. If so, the capability unit X manager should work with the manager of capability unit Y to develop the changes. However, capability unit Y may have other users, such as capability units M and N that are not apparent to capability unit X. Thus capability unit X may need to engage both capability unit Y and all the users of capability unit Y to accomplish the change. The change should occur easily if all users see a net benefit; otherwise, they either agree that it has value to the enterprise or the decision must be made at a higher level in the organization. This includes consideration of the cost of change as well as any increase in operating cost as compared to the business value of the change.

If a change to a service provider increases the cost or degrades the performance of a user, that user is in turn accountable to its users. In the diagram, suppose capability unit Y makes a change to improve the quality of its product, but this causes a cost increase. This cost increase is incurred by capability unit X along with the other services that use capability unit Y. This affects the obligation of capability unit X to its users, A, B, and C. This effect propagates up the chain of users until it becomes evident in one or more value streams or otherwise affects enterprise performance. At that level, the impact on the enterprise and the ultimate customer can be evaluated.

Changes that have a propagation of effect to one or more value streams must be evaluated in the context of relevant VDM scenarios. This will highlight the impact on value propositions and provide a basis for objective consideration of enterprise-level trade-offs.

One-Time Costs

Even if a capability unit manager makes a change that reduces cost over time, there may be an investment, and thus an increase in costs, incurred in the short term. It would not be desirable for all improvements to be impeded by opposition to cost increases by users. This should be addressed with an appropriate funding mechanism. The cost of change might be recovered over time, so improvements that would be recovered within a certain number of years would be authorized and amortized for cost recovery. The capability unit management chain has primary responsibility for making such changes. Changes that would increase the unit cost of services to users should be approved by the service user managers and/or the affected LOB managers. The enterprise must establish appropriate procedures to ensure an appropriate level of budgeting, approval, and concurrence by affected managers.

For example, a machine repair capability unit may determine that an investment in a diagnostic tool would reduce the cost of repairs. If the return on investment is acceptable, the cost of the tool can be prorated, reflecting the return on investment so that there is no net cost increase to service users. This would not affect the capability unit interface. On the other hand, shifting from a failure-response mode of machine repair to a preventive maintenance mode requires a different relationship with service users and thus a change to the service interface—which may put an additional burden on service users while reducing the impact of failures on the operations of the service users. This also requires a change in the cost model. This can be resolved through collaboration with service users but should still require enterprise-level approval of the interface change.

Changes Out of Scope

For a particular business change, there may be no solution that can be implemented within a single capability unit or through a collaboration among the service manager and service users. This may be because the change has long-term consequences or significantly impacts the enterprise product or service. The resolution of these exception events must be escalated to the LOB manager or managers. In some cases, the need for change may come to the attention of a capability unit manager but not have a direct bearing on his or her operation. Notices of these events should be posted for distribution to more appropriate recipients. If appropriate recipients have not been predefined, the event notice must be escalated up the management chain.

LOB Management

The LOB manager has a broader perspective on needs for change. The LOB manager is concerned about competitive position of value streams for the products or services that he or she manages and thus can assess the implications of changes in a market context. All LOB managers should be able to view the delivery of customer value in the context of a product life-cycle for their LOB (see the product life-cycle discussion later in this chapter).

A LOB manager will also have capability units that are unique to specific value streams or to the LOB. Some changes to these will be internal to the capability unit, but optimization of the particular LOB will always be the primary objective.

As with the capability unit manager discussed previously, the LOB manager may be able to work with one or more shared capability units to resolve changes of limited impact. These are essentially operational adjustments.

Observations that indicate a change in market demand or an opportunity for competitive advantage should be primarily directed to LOB managers and market analysts. They must translate a change in market demand to a change in sales forecasts, and then, using the value stream, they must determine the implications to the services used to deliver products or services. This may have a significant impact on the workload of service providers, but it might not require any change in functionality.

Some enhancements call for significant changes to the product or service or need to be coordinated across a number of services that are only indirectly related. For example, a new product technology may require changes in product engineering activities, production activities, field service activities, and supply chain relationships. The design and implementation of these changes requires cross-organizational coordination and control. VDM support for substantial transformation management is discussed later in this chapter.

These changes are more likely to involve improvements of value streams and value propositions of other lines of business. Planning and implementation must involve VDM modeling analysis along with collaboration among representatives of all the affected lines of business, the business architecture organization, and other shared services and business support services. These changes will likely involve changes to shared capabilities, and these must be reconciled with other lines of business that share those capabilities.

The Cost of Change

The cost of such changes must nevertheless be determined and considered in the decision to change. Change implementation may be owned by the LOB manager but managed and performed by transformation capability units. The affected provider capability unit managers have the primary responsibility for change implementation. If the change adversely affects their other users, the impact on those users is part of the cost of change and could be an increased burden on other LOBs. Unless the affected product lines agree, the issue should be escalated to the executive staff level in the organization.

Value stream relationships in a service-oriented architecture supported by VDM modeling make it possible to determine the full cost of change as well as the full cost of a product, including the indirect impact on related products and services. Each product is the result of contributions of value and cost from the services used to develop and deliver the product. Each service must report its true cost, including the cost incurred in using other services and the recovery of costs for improvements.

In some cases, a needed change has effects that reach beyond the responsibility of the LOB manager. This includes an opportunity for a new LOB, a need for substantial realignment of business operations, consideration of a merger or acquisition, or a technology change that exceeds a threshold for investment in new capabilities. These exceptional circumstances should be escalated to the executive staff.

Later in this chapter, discussion of a product life-cycle process reflects the requirements for collaboration with other organizations in the development and implementation of a new product or substantial LOB changes.

Enterprise Management

Transformation that has broad impact and requires coordination across major organizations must be managed from an enterprise perspective. These changes arise from new business opportunities and threats that are not specific to a LOB. This includes (1) consolidations of capabilities or significant changes to shared capabilities; (2) creation of a new LOB; (3) a merger, acquisition, divestiture, or outsourcing; (4) changes to customer or supplier relationships; and (5) introduction or upgrade of pervasive technology (typically information technology).

The executive staff should be aware of any circumstances, internal or external, that can cause significant and sustained change in market demand, operating costs, personnel, investment, and supply chain relationships for consideration of countermeasures or changes of strategy. Enterprise management must bring an overall perspective through strategic planning. Strategic planning and implications to the agile enterprise are discussed in the next major section. A transformation management process is discussed later in this chapter.

Virtual Enterprise Management

A virtual enterprise is an enterprise composed of multiple companies that work together for a shared purpose—a collaboration of companies. The companies involved in a virtual enterprise each expect to realize benefit from the collaboration, otherwise the virtual enterprise will not survive. This is represented in a VDM model as a business network exchange of value propositions.

The decision to participate in a virtual enterprise will be the result of enterprise management strategic planning. Strategic planning will continue to focus on the virtual enterprise relationships and the role of the parent enterprise in this business arrangement and the marketplace. See the discussion of strategic planning in the next section.

Industry Change

Generally, the purpose of the virtual enterprise is to create a stronger business than the participants can achieve on their own. Formation of a virtual enterprise suggests a change to a business model that is not consistent with current industry relationships. It will have a significant industry impact and will involve a greater investment, duration, and risk than a transformation that is contained and managed within the single enterprise.

While the industry change may involve multiple companies, one company will be the focus of the transformation as the company that will realize the major competitive advantage among its competitors, and likewise the one that will take the greatest risks, making the industry transformation a primary focus of that company's efforts for several years.

The participants will work together for seamless integration of their products and services and potentially participate in joint sales or integrated customer solutions. This will involve adoption or development of shared standards for seamless integration of complementary products and services as an aspect of the expected competitive advantage.

An industry change usually brings a new business model or at least a substantial change in the nature of a product or service. A radical change has the potential to take advantage of the cultural inertia of competitors because they are heavily invested and comfortable with business as usual.

Convergence of Factors

Generally, the change becomes viable because of the convergence of multiple factors—potentially multiple industries. Consider the introduction of iTunes by Apple. It was not just a new music download service, and it changed the recording industry—a new business model. There was already a transition to digital music, and cheap memory enabled collections of music to be stored on a small, portable device. Recording studios and artists were already losing to the distribution of pirated music. Apple gained the advantage of being first to provide the service to serve the market and develop relationships with members of the recording industry. A mass market was driven by low prices and easy access to a very large library of recordings that was more convenient (and legal) than access to pirated recordings.

The market factors did not suddenly change, they converged over time: digital music, very small player devices with lots of memory to hold many recordings, internet access to a library, recording companies and artists losing money to pirates, and an existing market of people enjoying their personal collections on portable devices. The strategy could have been developed much earlier. If it was introduced too soon, it might have failed. A key was to make the commitment and develop the details and relationships at the right time.

For Apple, the disruptive event occurred when there was a commitment to the strategy. For the industry, it occurred when iTunes was announced.

Of course, there was a lot more to the success of iTunes than commitment to a strategy. There was implementation of the service, synergy with mobile devices, the development of a profit formula, development of marketing strategy, the acquisition of content, and the delivery of value to the affected artists and enterprises.

So what could a competitor do? Could they have beaten Apple to market with an alternative service? Probably not. But they might have anticipated such a move and built a complementary strategy. Apple changed, not only the portable recording device industry, but the music industry as well.

So to create an industry change requires (1) an understanding of the marketplace, including the behavior of the end customers, (2) understanding of the potential of the core technology, (3) relationships with key participants, and (4) having the capability and courage to deliver.

Strategic Planning Framework

Strategic planning defines what the enterprise is now and what it is expected to be in the future. It is primarily the work of the executive team and supporting staff, but it must reflect the values and interests of the governing board and investors.

In the agile enterprise, strategic planning must be an on-going activity. In this section, we will first consider a conventional framework of strategic planning and then discuss how this might be modified to address the concerns and capabilities of the agile enterprise.

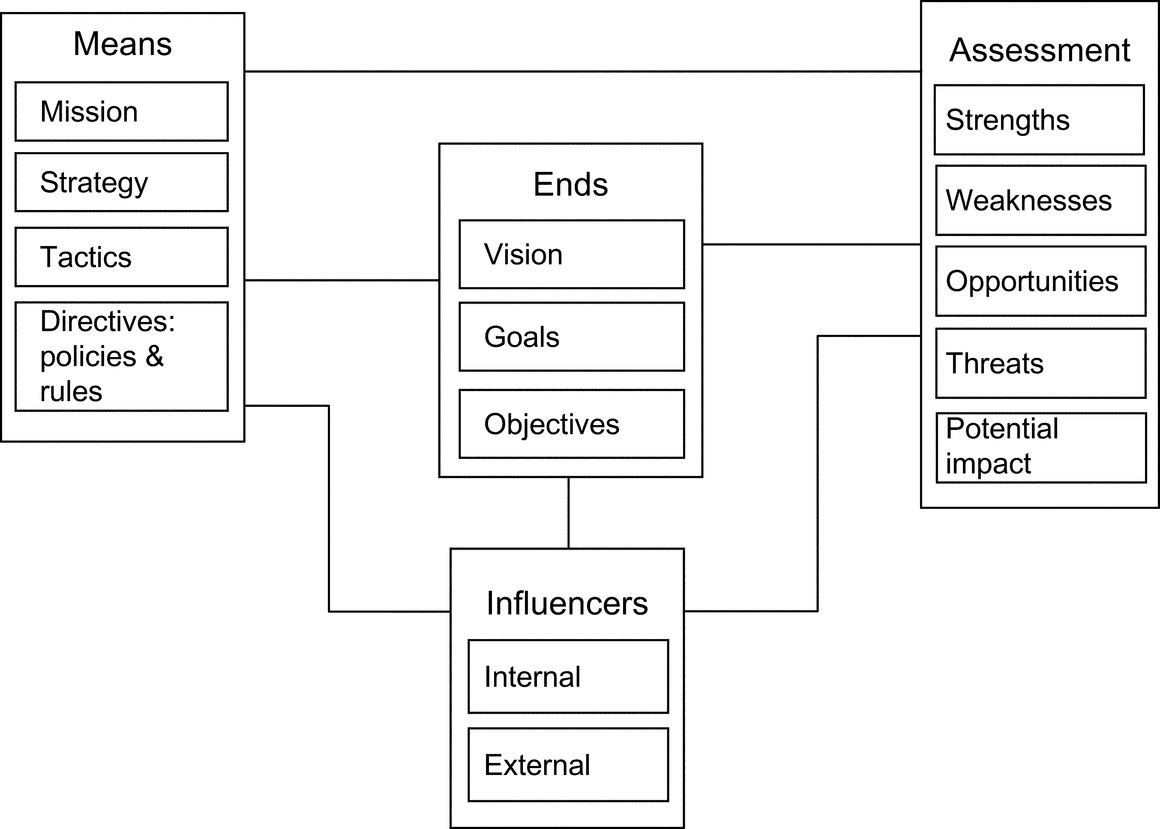

Conventional Strategic Planning

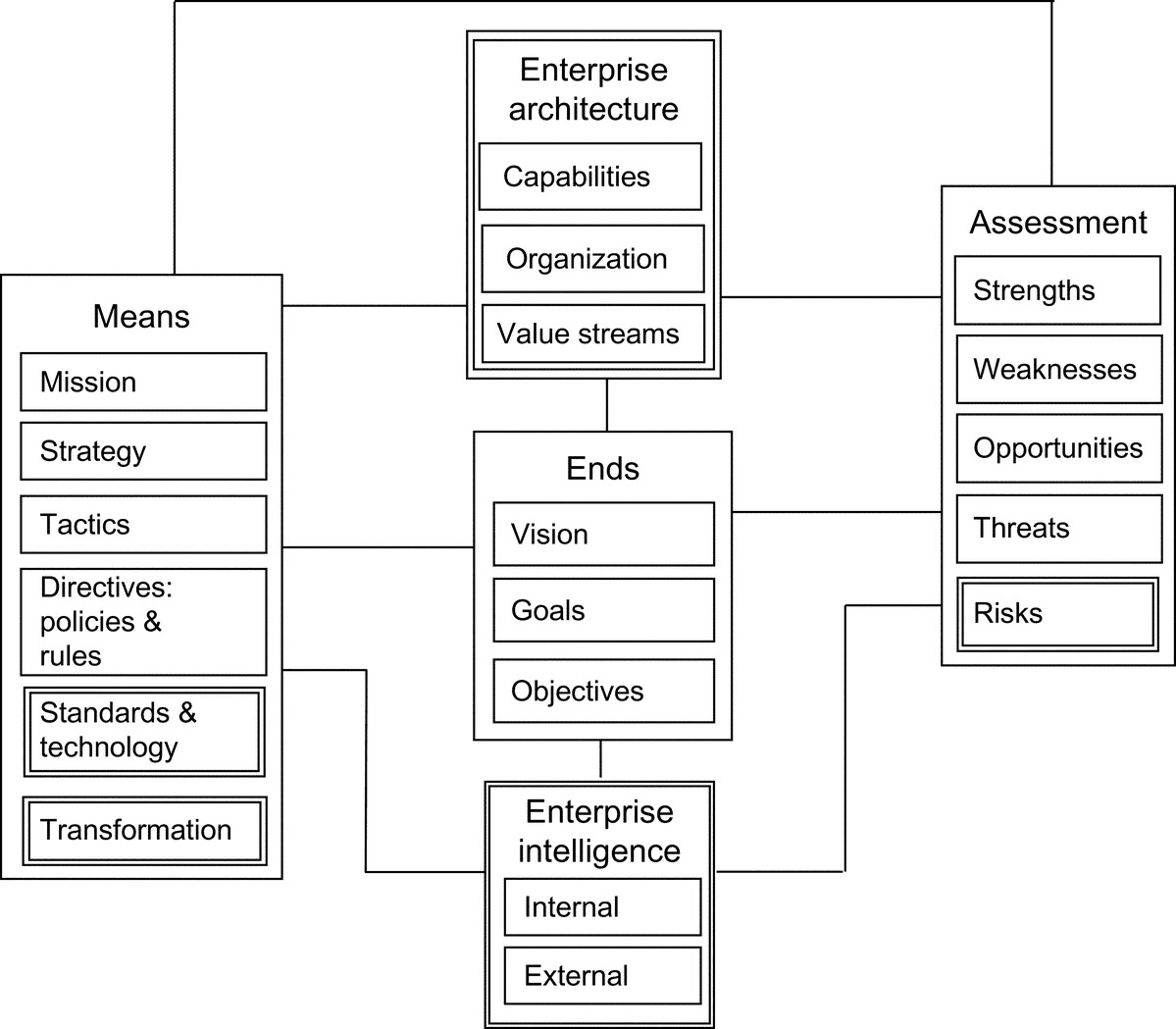

Fig. 9.3 depicts a high-level view of the BMM (business motivation model) strategic planning framework, an OMG specification. This structure has received widespread acceptance as a useful framework, and it is a good foundation for strategic planning for an agile enterprise. The concepts are typical of common strategic planning practices.

Strategic planning is primarily the responsibility of the CEO with the participation of his or her direct reports. At the same time, there is a need for a support staff to gather information, support the analysis, develop the work products of the strategic planning effort, and coordinate with related activities. The leader of the strategic planning capability unit typically reports to the CEO. The following points briefly describe each of the elements in Fig. 9.3:

Ends. Ends describe the ideal future state of the enterprise; they include vision, goals, and objectives.

• Vision. A vision is a future, possibly unattainable state of the enterprise. It may be a characterization of the way the enterprise should be viewed by others, for example, as leader in a particular industry, preferred employer, innovator, etc.

• Goals. Goals are more specific aspirations for the enterprise, but they tend to be on-going rather than having a point of completion. Goals support the vision.

• Objectives. Objectives are achievable, measurable results that support goals with a defined time of completion.

Means. Means are the mechanisms by which ends are pursued. The components of means are mission, strategy, tactics, and directives.

• Mission. The mission is a general statement of the on-going purpose of the enterprise—a generalization of the value to be produced.

• Strategy. Strategy is a plan or approach to supporting the mission and achieving ends, particularly with a focus on goals.

• Tactics. Tactics are specific, near-term actions in support of a strategy. Tactics typically focus on achieving objectives.

• Directives. Directives define restrictions or requirements on how business is conducted. They include policies and rules. Policies are high-level statements of intent. Rules are specific constraints on business operations.

Influencers. Influencers are sources of effects that must be considered in assessment and planning. Influencers can affect the conduct of business, positive or negative, but do not have direct action or control. There are internal and external influencers.

• Internal influencers. Internal influencers are things within the enterprise, such as culture, attitudes, thought leaders, infrastructure, beliefs, and capabilities, that influence how business is approached or conducted and how new ideas are developed.

• External influencers. External influencers come in a wide variety, such as competitors, customers, the economy, governments, and technology. Changes in these influencers may have a significant impact on business opportunities or the viability of the enterprise or its undertakings. These are sources of change outside the enterprise. See the section on drivers of change, earlier in this chapter.

Assessment. Assessment deals with the evaluation of the impact of specific current and changing factors that should be considered in planning future pursuits or direction. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats (often referred to as SWOT) are not a normative part of the BMM specification but are widely used. Strengths and Weaknesses are internal; Opportunities and Threats typically come from the environment. Influencers, along with strategies, tactics, and transformation plans, are inputs to assessments. An assessment effort will determine potential impact.

• Strengths. Strengths are those factors that make the enterprise competitive or give it competitive advantage. Strengths are important in considering new undertakings.

• Weaknesses. Weaknesses are those factors that could put the enterprise at a disadvantage with respect to competitors or the capability to undertake a new pursuit.

• Opportunities. Opportunities represent potential growth or improvement of value and include such things as new endeavors, new markets, and advanced technology that may create a new market or provide competitive advantage.

• Threats. Threats are circumstances that could put the enterprise at risk. These may include actions by competitors, economic, political or social events, natural disasters, supplier failure, shortage of resources, or lawsuits. They may include missed opportunities that could impact market share.

• Potential impact. Potential impact captures the results of assessments—potential gain or loss. Typically, the affects of these impacts are relative to current or future business endeavors.

Adaptations for the Agile Enterprise

Fig. 9.4 depicts the BMM framework modified to support strategic planning for an agile enterprise. The modifications are highlighted with double boundaries.

We have made five changes: (1) expanded on the content of vision, (2) added business architecture, (3) changed influencers to enterprise intelligence, (4) replaced potential impact with risks within assessment, and (5) added transformation and standards and technology to means.

These five changes not only connect strategic planning to the operation of the enterprise; they provide the means for insight and participation in governance by the Governing Board. Along with Strategic Planning, these changes align with the executive staff capability units described in the organization structure in Chapter 10. We discuss their roles in strategic planning activities in the following list, and their broader capability unit capabilities and responsibilities in the organization structure discussion.

Vision. The content of Vision is expanded here based on Collins and Porras (1996). These added elements provide a stronger corporate identity.

• Core ideology. The core ideology consists of two elements that could persist for as long as the enterprise exists:

○ Core values. A few guiding principles for the operation of the enterprise.

○ Core purpose. The most fundamental reason for the existence of the enterprise.

• Envisioned future. A significant ambition for the future.

○ Audacious goals. These are inspirational goals that may not be possible.

○ Vivid description. An inspirational vision of what the enterprise should be in the future.

Business architecture. Adding this component makes the design of the business a key part of strategic planning. It provides insight on both the current enterprise design and implications of potential designs of the future. Within the Strategic Planning activities, Business Architecture is a component supported by the Business Architecture capability unit, discussed later. There are three key components that support the strategic planning process: Capability Units, Organization, and the Value Streams.

• Capability units. The capability units component is a model of the formal, integrated capabilities of the enterprise, which support the Means and are the basis of the Assessment. Capability units and resources for the capability units are managed and leveraged by the organization. Capability units are an addition to the standard model because they are the building blocks for implementation of Strategies and Tactics, and they are the focal point for assessing Strengths and Weaknesses as well as Risks. Specification, configuration, and implementation of capability units become means to realization of the strategic plan.

Capability units are also the targets of strategies and tactics. Strategies and tactics are developed for capability units when we address threats and opportunities, possibly requiring some adaptation of existing capability units and occasionally requiring the development of a new capability unit. The investment required to implement strategies is lower and more predictable with capability unit building blocks. For the most part, shared capability units remain stable as the products or services of the enterprise change. This means that they continue to operate effectively and potentially continue to improve.

• Organization. The organization structure defines responsibility for management of operations, resources, and facilities to fulfill capability unit requirements. The business architecture must align organizational goals and incentives as well as other factors that achieve synergy, to promote optimal performance of capability units. The organization structure is not the capability unit integration network but instead represents the relationships between people that manage and participate in capability units, perform the work, and adapt the enterprise to changing business needs. Organization design is discussed in Chapter 10. The organization structure also determines the responsibilities of managers for compliance with rules and regulations and mitigation of risks.

• Value streams. The value stream concept is fundamental to VDM model. A value stream defines the network of capability units that contribute to the deliverables and values delivered to a customer. The enterprise consists of a number of value streams. The primary value streams produce end customer value and generate revenue for profit-making enterprises. Other value streams produce value for internal customers and stakeholders.

In many cases, the focus for strategic planning is on value streams and the participating capability units to deliver value, manage cost, and ensure compliance with rules and regulations. Analysis of a production value stream reveals the contributions of cost, quality, and timeliness of individual capability units in the delivery of results to customers. This provides perspective on where to invest in improvements.

In evaluating new products and assessing a LOB, the full life-cycle of products and service offerings should be considered as discussed later in this chapter. VDM analysis of a potential value stream can reveal both the ability or inability to deliver value and the direct impact on other operations and lines of business of the enterprise, including the utilization of strengths and the need to resolve weaknesses.

In the past, there has not been a direct linkage between the strategic objectives and the design of business operations to achieve those objectives. Generally, strategic planning has relied on the mental models of executive leadership to identify required changes and define initiatives for change. Initiatives can suffer from the lack of a detailed and balanced understanding of the effort required and the consequences to the rest of the enterprise.

In the agile enterprise, value streams make it all real. They are the connection between change at a strategic, enterprise-level and the operation of the business, both in terms of current operations and future plans.

Enterprise intelligence. As a component of strategic planning, enterprise intelligence provides visibility of the current state of the enterprise and provides insights on forces for change—those influences, both from inside and outside the enterprise, that affect the operation and future of the enterprise. Enterprise intelligence includes knowledge management, analytics and data warehouse, and it is the primary manager of information regarding observations on changes to the enterprise ecosystem. Note the section on drivers of change earlier in this chapter. Enterprise intelligence also provides input to the formulation of ends and the assessment of means. It gives an enterprise perspective on both the data collected and the presentation of information for planning and decision making.

Assessments. Risks are added to assessments.

• Risks. Risks are the potential effects of opportunities and threats on the success of the enterprise. Risks include latent risks in the design and management of the enterprise as well as risks associated with the pursuit of enterprise initiatives and noncompliance with regulations. This is the assessment aspect of risk management. An audit and risk assessment capability unit, discussed later, provides the capabilities needed to assess compliance and risks along with mitigation.

Means. Transformation and standards and technology are added to means.

• Transformation. Strategic initiatives require more than statements of strategy, tactics, and directives. They require planning, coordination, and accountability. The transformation component addresses the broader scope of concerns associated with changing the enterprise to achieve strategic objectives. A transformation management unit provides the capability to address this strategic planning component and provide visibility into transformation plans and progress. The transformation management process is discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

• Standards and technology. This makes specification of standards and the selection of technology a key component of strategic initiatives. Standards and technology are important to both products of the enterprise and the internal operation of the enterprise. For organizational agility, standards are essential to interoperability of capability units; the ability to combine and compare data from multiple sources; and the efficiency, reliability, and flexibility of information systems. A standards and technology capability unit, discussed later, provides the capabilities needed to address this strategic planning component.

Transformation Planning

Strategic planning should work closely with business architecture to define a “to-be” business design at sufficient detail to validate the intended changes to the business from an executive perspective. Business architecture must then further refine the design with additional levels of detail to establish the consequential changes at the level of specific capability units to provide a clear definition of requirements for the transformation planning and management.

Currently, VDML can be used to provide one or more business scenarios representing stable states of the business. The to-be model will represent a desired future stable state and an as-is model will represent the current state. In general, it will be desirable to create models for intermediate stable states representing phases of transformation.

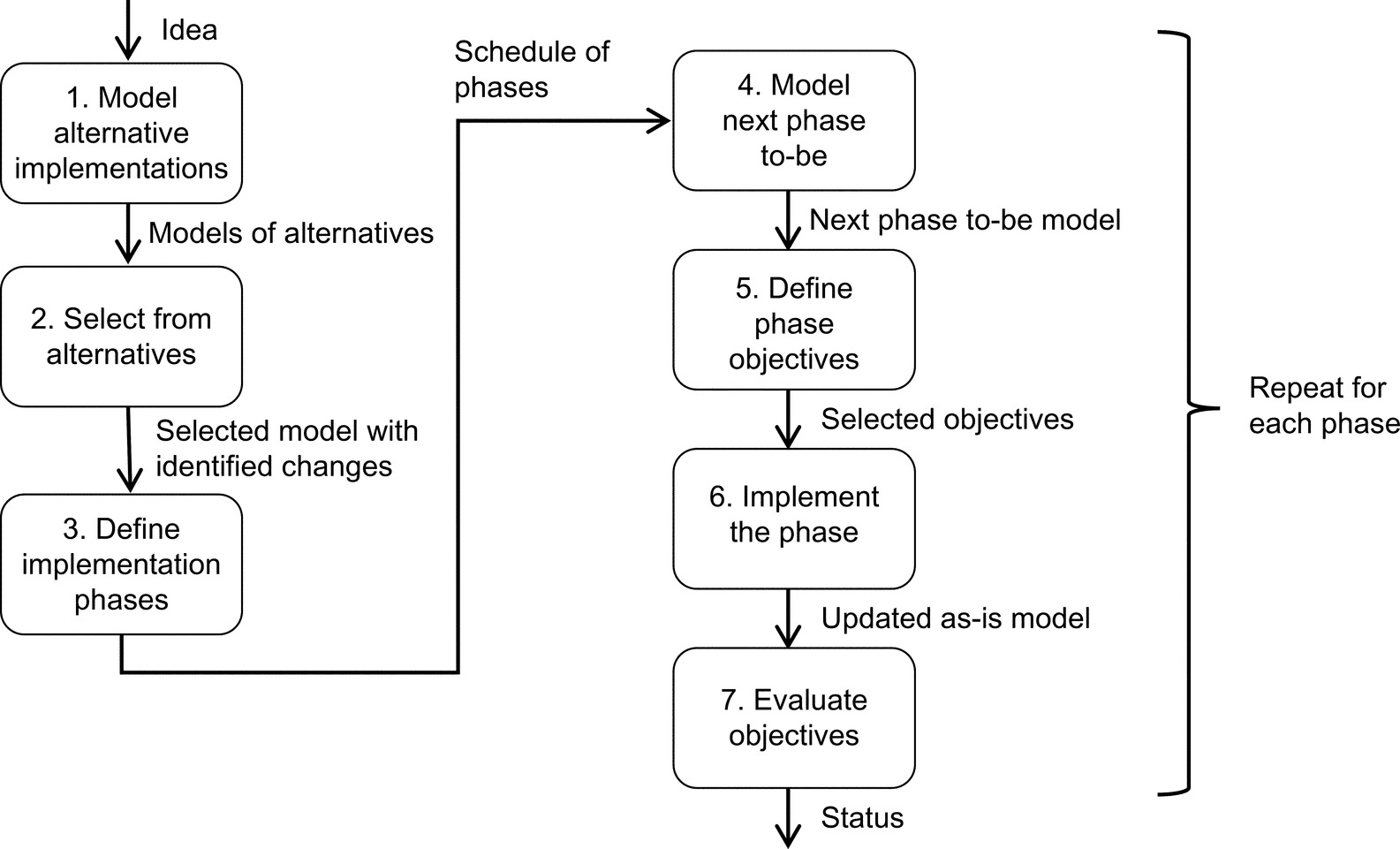

In order to manage the transformation, it is necessary to determine the specific changes that are required to transform from one phase to the next and identify dependencies between these changes. Fig. 9.5 depicts that process.

These changes are effectively activities in a transformation plan, and the dependencies between changes are dependencies between the transformation activities. Selected changes are then the basis for definition of strategic objectives for progress reporting to management. Of course, the transformation plan becomes the basis for more detailed monitoring of progress.

The VDM business design model enables the implementation of many changes to be delegated to the LOB managers or the individual service managers, as long as the requirements and scope are defined by the VDM model and the solutions are not suboptimal from an enterprise perspective. The VDM model will identify the relationships between a capability unit and other capability units and multiple value streams for consideration of propagation of effects.

Substantial transformations take years, and new circumstances will emerge that require response before the current transformation is completed. In addition, phases support periodic evaluation of progress and possible course correction.

The following sections describe a process for planning and management of phased business transformation supported by VDML (Fig. 9.5).

Model Alternative Implementations

VDML provides the ability to represent an implementation with enough detail to identify the capabilities affected and new capabilities required, if any. This provides a reasonable basis for estimating the cost and duration of transformation. The value stream analysis will provide an assessment of the value contributions and potential customer value proposition(s). The details of these estimates should be supported by the organizations that are or will be responsible for the contributing capabilities.

Select From Alternatives

Management consideration of cost, duration, and customer satisfaction provides the basis for validation of the proposed business change as well the basis for selection of the best alternative. It is likely that it will be necessary to consider trade-offs between cost, timeliness, and customer satisfaction.

The result of this step is a clear, consensus definition of the final, to-be business configuration. This provides the basis for continued alignment as operational details are developed by participating organizations.

Note that over the course of the transformation, new factors and potentially new strategies will arise, and it will be necessary to revise the to-be business configuration to provide new, refined guidance to the transformation participants and the details of the transformation plan.

Define Implementation Phases

Phases of implementation should be based on the expected, overall duration of the transformation, the significance of the changes, and the necessity for coordination of changes among different organizations and their capabilities. Each phase should be an incremental step in the right direction, ending with a business configuration that is acceptable and stable until completion of the next phase.

This may require a fairly detailed analysis of the dependencies between capabilities and their effects on customer satisfaction for the target value stream as well as other value streams that might be affected.

Model Next Phase To-Be

While the overall plan should define the expected phases, the next phase, for each iteration, will require the most detail and must reflect the actual results of the preceding phase. Progress on each phase will not be perfect, some assumptions will be revised and some phase objectives will not be met, so the next phase will require some adjustments. Each new phase is based on this step.

Define Phase Objectives

Each plan for the next phase should identify critical success factors (objectives) for that phase so that progress can be monitored by management and timely adjustments can be considered for the plan and availability of resources. The achievement of these objectives, or not, provides a basis for detailed planning of the next phase.

Implement the Phase

This is where most of the work gets done. The capability methods and resource requirements of the VDM model are transformed to development of changes in service interfaces and service level agreements, business processes and applications, acquisition of facilities, and staff training and recruiting.

Evaluate Objectives

The completion of each phase must be evaluated against objectives. Success should be further evaluated by consideration of the value measurements once the completed phase has become operationally stable. Some capabilities may require further refinements to realize expected value contributions. Unless this is completion of the final, to-be phase, the transformation proceeds with the model next to-be phase step, mentioned earlier.

The final phase should achieve the design and expectations of the originally anticipated, final, to-be business design. However, by that time, there will likely be new, strategic objectives and a new, final, to-be business design. Strategic planning and transformation should become a continuous process.

Example Product Life-Cycle

Implementation of a new product or LOB is an example of a different form of transformation. This process is effectively orthogonal to the above transformation process. For the most part, the production engineering stage is where the new value stream is implemented.

It is possible that the new product value stream is only a reuse of existing capabilities. However, if there is a requirement for new or modified capabilities, these should be incorporated in transformation planning as discussed in the previous section. It is most likely that such changes will affect the production operation value stream rather than the other stages discussed below.

The goal of the new product life-cycle is to develop and implement the delivery and support of a new product. This will involve one or more product development value streams that together spans the product life-cycle from concept to field support.

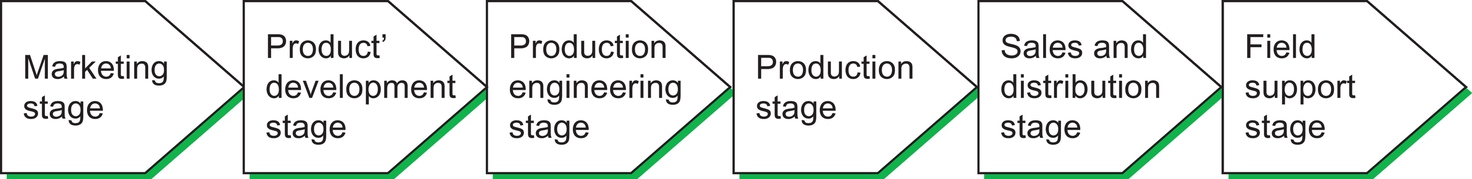

We use a value chain perspective, illustrated in Fig. 9.6, to define stages in the life-cycle. A value chain typically depicts general stages in the development and delivery of a product or service to a customer—it does not depict a flow of deliverables like a value stream. Different industries and companies will have different value chains but with a similar purpose. In this example, we use a value chain of a hypothetical manufacturing company.

The capabilities of each stage of a value chain tend to be distinguishable in the personnel and other resources involved, as well as their unit of production for delivery of a new product. Therefore each stage will have a relatively distinct set of capabilities, and we have used those distinctions as the basis for bringing together shared services that support that stage, both for product development and for on-going support for business operations in an example organization model in Chapter 10.

The work of a stage does not end when the next stage begins, but it shifts to a different mode of support.

Consideration of the life-cycle of a hypothetical product will illustrate how different shared services organizations interact and contribute value to the end product. We use a value chain based on a manufacturing enterprise with stages marketing, product development, production engineering, production, sales and distribution, and field services. We will step through these stages focused on contributions to the development and refinement of the product and its value stream.

The LOB responsible for the product is responsible for managing the overall collaboration that drives the product life-cycle capabilities including an on-going change management collaboration. The LOB-driven collaboration will engage shared services in each stage as well as interorganizational collaborations. Development of the product vision and commitment to development occurs in strategic planning prior to initiation of the marketing stage. Value contribution measurements will be captured and reported throughout the life-cycle. The start of each next stage is a major milestone based on readiness and continued commitment.

We assume the enterprise is an established manufacturer with an established LOB, and we are implementing a new product. Note that this is not intended to be a recommended or complete model, but only an illustration of the interorganizational collaborations and capabilities involved in each stage.

The LOB product management team develops the details of the product life-cycle services as the life-cycle develops, and the overall coordination and tracking of progress is performed by the enterprise transformation management unit.

Marketing Stage

The marketing stage is enabled by a strategic plan defining a product vision, a management commitment to initiate the marketing stage, and creation of a product management team in an appropriate LOB.

The marketing stage solidifies plans for development of the product to support an enterprise commitment to the next stage. Marketing has participated in strategic planning in support of the product vision and the decision to proceed with the marketing stage for this product.

Marketing

• Marketing will perform further and on-going market analysis based on analytics and studies in order to clarify the market segment(s), the expected product volume and lifetime, and the competitive position.

• Market segments and initial value propositions will be developed based on assessment of customer values and priorities, particularly pricing.

• Marketing will collaborate with enterprise architecture, product development, and production engineering regarding product design, features, and cost.

Business Architecture

• Enterprise architecture has participated in strategic planning for this initiative and has developed an initial production value stream model to assess capability requirements, key competencies, cost of implementation, and production costs.

• A business model cube (see Lindgren under Related Business Analysis Techniques in Chapter 2) has been developed with strategic planning and will be refined along with development of more detail in the value stream model.

• One-time and recurring cost estimates will be developed in collaboration with product development and production engineering.

Strategic Planning

• Strategic planning will continue to collaborate with marketing, enterprise architecture, and the responsible LOB organization regarding the product vision, the business model cube, market assessments and the implementation cost, status, and objectives.

Regulatory Compliance

• Regulatory compliance will collaborate with enterprise architecture, product Development, and production engineering to review the product features and the production value stream to identify regulations that may apply to product features, materials, or production operations.

Product Development

• Product development will develop a conceptual product design in collaboration with marketing, the responsible LOB organization, and enterprise architecture. This conceptual design will be the basis for further feasibility analysis, refinements to the value stream model and cost estimates.

Production Engineering

• Production engineering will assess production capabilities based on the production value stream model, and will identify key suppliers (outside capabilities), costs of equipment and facilities, and production staff skill requirements.

• Production engineering will collaborate with production regarding the impact on staffing, facilities, and equipment.

Human Resource Management

• Human resource management will assess staffing requirements in collaboration with production engineering and production.

• Human resource management may need to support temporary or contract staffing for the preproduction stages.

Finance and Accounting

• Finance and accounting will develop financial plans and budgets in collaboration with the involved organizations.

• Accounting will establish accounts for cost accounting and track one-time and recurring costs throughout the life-cycle.

Risk Management

• Risk management will collaborate with the LOB organization, marketing, product development, and production engineering to assess market risks, operational risks, and product liability risks associated with the new product.

• Risk management will also participate in the change management collaboration.

• Risk management will collaborate with other organizations, as required, to mitigate risks.

Product Development Stage

The product development stage will begin with a decision by top management that the product will be viable and profitable, and that the costs and risks are acceptable.

Product Development

• Product development will develop a complete product design. The design will be refined based on collaboration with marketing and production engineering considering customer appeal, value propositions, and manufacturability.

• Product development will include development of prototypes and product testing.

• Product development will develop product maintenance, diagnostic, and repair materials for field support as well as user manuals.

Business Architecture

• Enterprise architecture will continue to refine the production value stream model based on collaboration with the LOB organization, product development, and production engineering.

Production Engineering

• Production engineering will collaborate with product development regarding manufacturability and production capability requirements.

• Production engineering will identify requirements for suppliers and their capabilities.

• Production engineering will periodically refine estimates for facilities, equipment, and staffing based on further development of the product design and the value stream model.

Marketing and Sales

• Marketing, in collaboration with sales and the LOB organization, will develop a marketing plan including advertising, incentives, product configurations and features, sales projections, and threat analysis.

• Proposed pricing will be developed in collaboration with finance and accounting, the LOB organization, production engineering, and production.

Risk Management and Regulation and Policy Compliance

• Risk management along with regulation and policy compliance will continue to participate in collaborations to identify risks and relevant policies and to mitigate risks and ensure compliance.

Production Engineering Stage

The production engineering stage begins when the product design is determined to be sufficiently complete. Additional product design refinements will be required as further testing and development of production capabilities identify design problems, or marketing identifies changes in customer interests or competition.

Production Engineering

• Production engineering will continue to collaborate with product development regarding production capabilities.

• Production engineering will acquire facilities, install equipment, develop tooling, and develop manufacturing processes.

Procurement

• Procurement will collaborate with production engineering to acquire facilities, equipment and tooling, and to negotiate contracts with suppliers.

Human Resource Management

• Human resource management will collaborate with production engineering and production for recruiting and training of production personnel.

Information Technology

• Information technology will collaborate with production engineering, production, distribution, sales, and field services to implement necessary changes to systems to support the new product.

• Information technology will work with enterprise architecture, production engineering, and production to implement new or changed capability unit business processes.

Production

• Production engineering will collaborate with production regarding testing of new equipment, tooling, and manufacturing processes as well as staffing and staff training.

• Production will collaborate with information technology regarding information system requirements and implementation.

• When new capabilities and processes are in place, production engineering, and production will collaborate in pilot production operations.

• Product engineering will collaborate with product development and marketing in testing and evaluation of the products from pilot production.

• Supplier schedules and initial parts inventories must be established in anticipation of production.

Marketing and Sales

• Marketing in collaboration with sales will develop advertising along with sales projections.

• Marketing and sales will make arrangements with channels, develop sales materials, and provide staff training materials.

Sales and Information Technology

• Sales and information technology will collaborate to implement changes to sales forecasting and order processing and tracking.

Field Services

• Field services will collaborate with product development to refine maintenance and repair materials and train staff.

Risk Management and Regulation and Policy Compliance

• Risk management and regulation and policy compliance will continue to participate in collaborations to identify risks and relevant regulations and to mitigate risks and ensure compliance.

Production Stage

The production stage starts when the product design and production engineering are completed and facilities, equipment, materials, capabilities, staff, and business partner relationships are in place to sell, produce, and support the product.

Effectively, the distribution and sales stage and the field support stage are enabled at the same time as the production stage, but from a customer and product flow perspective, sales and distribution come after production (except for a build-to-order product), and field support comes after sales and distribution.

Production Operations

• Production will collaborate with marketing, product development, and production engineering to improve production operations.

• Production will collaborate with production engineering for changes to production capabilities.

• Any changes to shared, production capability units must involve collaboration with other recipients of the same services to resolve any impact on their value measurements or changes in the service interface.

• Individuals in the production organization will come up with innovative ideas to improve operations or the product. They will collaborate informally within production before collaborating with marketing, product development, and/or production engineering regarding potential implementation.

• Production operations will fill the pipeline to support the production process.

Finance and Accounting

• Finance and accounting will participate in collaborations regarding the budget impact of product or production changes and changes in production volumes.

• Accounting will establish cost accounting and unit cost measurements for the new product production value stream.

Marketing

• Marketing will continue to monitor market trends and disruptions and collaborate on their impact on production schedules, product design, pricing, advertising, and promotional campaigns.

Product Development

• Product development will develop product improvements and collaborate with production engineering and production as required to implement the revisions.

Sales and Distribution Stage

The sales and distribution stage is enabled at the same time as the production stage, but from a customer and product flow perspective, sales comes after production (except for a build-to-order product).

Marketing

• Marketing and sales collaborate on advertising, promotional campaigns, impact of market trends, and responses to competition.

• Marketing, sales, and product development collaborate on product design options and improvements.

Sales and Distribution

• Sales and distribution collaborate with product development and production engineering regarding customer complaints and defects.

• Sales will deploy sales training and advertising.

Procurement

• Procurement must evaluate and reconcile carrier and supplier contract compliance.

• Procurement collaborates with sales and distribution regarding complaints about carriers.

Field Services Stage

The field services stage is enabled at the same time as the production stage, but from a customer and product flow perspective, field services comes after production and sales and distribution.

Field Services

• Field services collaborates with product development and production engineering regarding product failures and problems with maintenance and repair.

• Customer services collaborates with marketing and product development regarding customer feedback.

• Field service personnel will be trained in product maintenance and support.

Business Change Support

People throughout the enterprise represent a valuable resource for identification of emerging threats and opportunities as well as insights and creativity in the development of solutions. However, these contributions need to be orchestrated for a harmonious result.

A VDM model provides a shared understanding of the dependencies and propagation of effects of changes so that these different perspectives and initiatives are aligned. In this section, we discuss the roles of executive staff units in unifying these efforts.

Strategic Planning Unit

A strategic planning framework has been discussed in the previous section. Strategic planning is the responsibility of top management, but it must be supported by a team that facilitates the discussion and pulls together the detail of an enterprise strategic plan. The strategic plan is no longer a document prepared every 3 years with a consensus of abstract ideas, but rather a constantly changing framework for guidance of efforts to evolve and adapt the enterprise to address threats and opportunities in a changing world.

The strategic planning team must consider how various initiatives, from capability unit incremental improvements to radical, industry initiatives fit into the strategic plan framework (or don’t). The executives must also use VDM to validate initiatives and defined transformation phases, and they must consider the risks of strategic plans and initiatives. This may affect approval and funding for some initiatives, consolidation of some initiatives, alignment of timetables for related initiatives, or guidance regarding enterprise priorities. This requires close communication between the strategic planning, enterprise architecture, and response oversight.

Transformation Management Unit

The transformation management team is responsible for coordination, collaboration, and tracking of threats and opportunities and resulting transformation initiatives at two levels: the sense and respond directory and program and project management.

Sense and Respond Directory Unit

Transformation begins with a recognition of a threat or opportunity that requires some response. The sense and respond directory accepts notices of observations that require attention and it links that notice to appropriate persons or processes for awareness and a response. This result may range from resolution with no further action to exploration of emerging trends and technologies, to initiation of major transformation initiatives. The purpose of this service is to keep track of all the business change related activities and facilitate communication where there is potential synergy or overlap and to ensure that observations get appropriate attention and follow-up.

With a multitude of employees and internal interest groups exploring potential threats and opportunities, there could be a lot of duplicated and inconsistent effort. This directory might include taxonomies for products, technologies, and capabilities for assignment of individuals as contact persons to receive distributions of notices and for ensuring that all areas of interest are monitored at some level.

Based on the taxonomies, topics can be directed to persons with particular interest, or a person higher in the hierarchy should accept a notice to determine who should follow-up. The follow-up person can then be added to the hierarchy for that topic.

Tracking of the response will continue until some action has been taken or initiated. When action is initiated or action has been taken, the disposition of a threat or opportunity will be reported and conveyed to the originator and other interested parties.

If a transformation effort is initiated, large or small, a link to that effort will be captured with milestones identified. As milestones are achieved, these are to be reported and communicated to interested parties.

Status and progress notices may be distributed through the general notification service once an implementation effort is identified.

Program and Project Management Unit