The Agile Organization Structure

Abstract

The traditional business organization structure focuses on the management hierarchy. Unfortunately, much of the way the enterprise actually works is not visible in a hierarchical organization chart. Furthermore, the sharing of capabilities in an agile enterprise occurs across the traditional organizational boundaries and requires a form of matrix organization structure in addition to collaborations of various forms that cross organizational boundaries. This chapter describes an appropriate organizational structure and relationships of the agile enterprise from five perspectives: the governing body, the executive staff, administrative support organizations, business operations, and interorganizational collaborations. Highlights of a transformation are identified in the context of the Value Delivery Maturity Model of Appendix A.

Keywords

Agile organization; Response escalation; Interorganization collaboration; VDM transformation; Value delivery maturity; Shared services matrix; Agile organization maturity

An enterprise organization structure defines the relationships among people, along with their respective responsibilities and authority, as the basis of their collective efforts to achieve enterprise objectives. It also defines the chains of command through which enterprise management exerts leadership, accountability, and control of resources.

Current-day organization hierarchies often reflect groupings of people engaged in functionally related activities. However, in some cases, the clustering is based on business relationships required decades ago, the remnants of mergers and acquisitions, or the independent evolution of various product lines.

An agile enterprise changes these relationships by breaking down departmental silos into value streams and shared services driven by value delivery. The participation and relationships of people continue to be important in the agile enterprise, but the workforce has shifted from performing rote production tasks to knowledge work: maintaining capabilities, managing exceptions, and resolving needs to address business challenges and opportunities.

In the agile enterprise, we combine the workforce shift to knowledge work with shared capabilities and a network of services, contributing to value streams that deliver enterprise values. Service units provide enterprise capabilities that can be engaged in a variety of enterprise pursuits. This is a sort of “hyper-matrix” structure because collaborations are connected by deliverable flows; value streams; responsible organization units; delegations from service to service; delivery of events; and teams for planning, coordination, innovation, problem solving, and other purposes that involve interorganizational participation.

The management hierarchy in an agile enterprise is a hierarchy of organization units responsible for budgets, personnel, and other resources, from the collaboration of top management to service units with people who do the actual work of the enterprise. The grouping of organization units under a parent organization unit brings together organization units that have similar capabilities and operating characteristics that enable them to work together for economies of scale and comparable leadership and incentives. The organization hierarchy is not about products, but about capabilities.

At the lowest level, capabilities are implemented by service units that perform the management and operational details to perform capabilities and contribute to value streams. Similar service units are grouped together in a parent organization unit. The parent organization unit operates at a more abstract level to manage the service unit and report to the next level in the hierarchy. At increasing levels, the collaborations become more abstract and the composite capability becomes more general.

The management hierarchy, for the most part, brings together service units that have similar capabilities and objectives. The primary objective of the management hierarchy is to optimize the operation of its service units and to adapt the service units to changing business requirements.

In the following sections, we begin by considering the impact of the VDM perspective. We then will outline agile organizational design principles. Next, we will discuss an example, high-level organization structure. Finally, we consider a general approach to transitioning an organization to achieve the agile enterprise based on the Value Delivery Maturity Model in Appendix A.

VDM Perspective

Value delivery modeling (VDM) brings three important perspectives to the design of an enterprise organization: (1) the collaboration network, (2) shared capabilities, and (3) value streams.

The Collaboration Network

The basic structure of the organization is changed by collaborations as a basic unit of composition. A collaboration engages people and other collaborations to accomplish its purpose. Collaborations include loose associations at one end of a spectrum, and formal organization units at the other end. Collaborations of various forms define all working relationships in and between enterprises.

VDML (Chapter 2) defines four specialized types of collaboration: business networks, organization units, communities, and capability methods. Business networks define relationships between the enterprise and other business entities. A community is a loose association of members with a common interest that may form more structured collaborations for initiatives of community interest. A market segment is considered a community collaboration among customers with shared product interests. An organization unit is part of the formal enterprise structure and is responsible for the management of people and other resources and facilities including funding. A capability method defines an application of a capability through a recurring collaboration pattern as a service.

A hierarchy of organization units forms the traditional management hierarchy that is extended to additional collaborations that manage resources such as project teams and business transformation initiatives. A capability method is performed by an organization unit that is responsible for the assignments of people, availability of resources, and management of capability method performance. Interorganization collaborations define interactions between members of different organization units to do work for enterprise purposes ranging from transformation planning to ad hoc problem resolution meetings. The network of collaborations involves all of the people engaged in the work of the enterprise, many people in multiple collaborations. Most of these collaborations are not represented in typical organization structure diagrams.

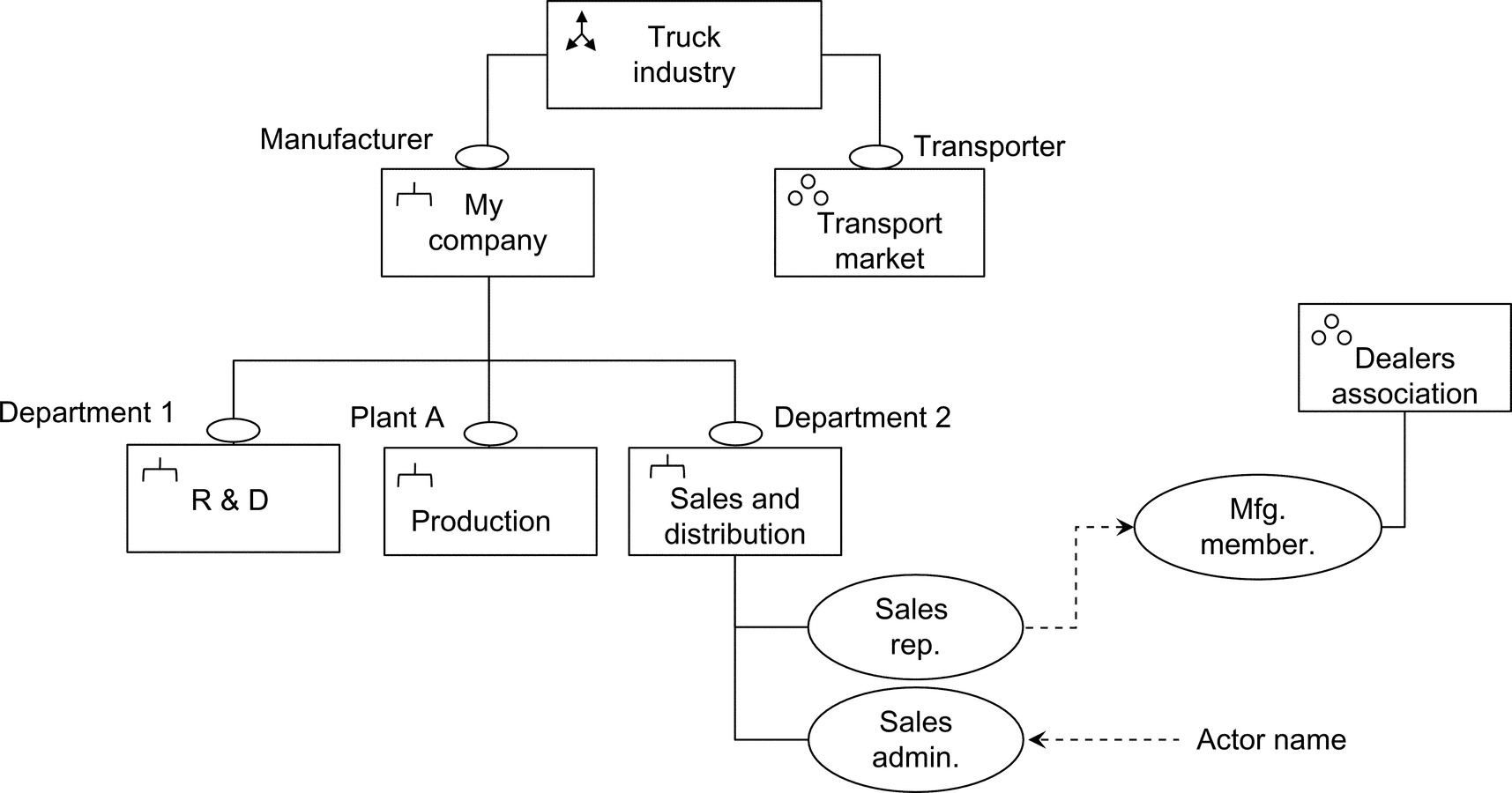

Fig. 10.1 illustrates a segment of an extended organization structure model using the VDML graphical notation. This diagram depicts representation of collaborations beyond the traditional management hierarchy. The rectangles each represent a collaboration. Those with a fork icon represent organizational units. Those with a three arrow icon represent business network collaborations. Those with a three circles icon represent communities. An ellipsis represents a role. Each collaboration with a small ellipse on top has in a role in the connected collaboration. A large ellipsis represents the role of a person in the associated collaboration. The dashed lines indicate that the role at the source of the arrow is assigned to the role at the head of the arrow. So the Sales Representative fills the role of a Manufacturing Representative Member in the Dealers Association.

Obviously, a more complete organization diagram could become very complex. However, such an organization structure should be accessed on-line since it will include collaborations and role assignments that are constantly changing, and the on-line service should provide for interactive viewing that allows the user to browse selected segments and abstractions of the overall organization structure.

Capability Units

A capability unit is an organization unit that manages the resources and performance of a capability. That capability unit can offer one or more capability methods for application of the capability. A capability method is a collaboration that specifies the activities, roles, and flows of deliverables that apply the capability as a service.

A VDM model captures a taxonomy of capabilities possessed by the enterprise in a VDML Capability Library and links those capability definitions to the capability offers of the organization units that perform and/or define the associated capability methods. The same capability may be performed by multiple, alternative organization units. VDM includes the analysis of consolidation and sharing of capabilities for economies of scale and control.

Each request for a capability method can involve different role assignments, different performance measurements, and different occurrences of deliverables. The capability method can engage other capability methods through delegation, or it may send a deliverable as input to another capability method—typically a message would be sent if the deliverable is input to a value stream for delivery of an independent product or service such as scrap from one process used to produce another product.

Through delegation and message sending, capability methods define a network of interactions and deliverable flows that represent the fulfillment of value streams and the overall operation of the enterprise.

A capability unit at the conceptual, VDM-level, corresponds to a service unit at an operational level. A service unit specification includes additional technical details and ancillary services that are not included in a VDM model. Ancillary services operate on active service requests for such action as requesting status or cancelation. Additional services of a service unit provide data management functions and engage administrative services. See more on service unit details and operational design in Chapter 3.

Capability methods (collaborations) are the building blocks of value streams. The enterprise can respond to new business opportunities by configuring a new value stream from existing capabilities. This implicitly defines the organizations that will participate in a new business.

Value Streams

A value stream is a network of flows of deliverables that converges at the delivery of a product or service to a recipient. Generally, there is a main stream that sets the pace, based on the receipt of customer requests or a production schedule. Alternatively, a value stream may be viewed as a tree structure with the root at delivery of the result and branches up the streams of deliverables. Multiple value streams can share branches at different levels where services are shared. Thus each capability method may be engaged in multiple value streams and may be involved more than once in the same value stream. Note that recipients of the result of a value stream may be internal consumers of the product or service.

A capability method returns a deliverable in response to a service request, and it delivers value measurements based on the specific use of the capability method. The value measurements can be defined in greater detail as contributions of value by each of the activities in the capability method. These measurements are based on a unit of production, and they are aggregated to support measurements for each type of value in one or more value propositions for the output of the value stream. Value propositions may differ for different customers based on different levels of customer satisfaction and priorities.

Value contributions of a capability method are the responsibility of the organization unit that performs the capability method and provides the resources. Value contributions affect every value stream in which the capability method is engaged, but the measurements will vary depending on the context in which the capability method is engaged. Thus the organization unit must be accountable for performance to its management chain and to each of the recipients of its services as well as the value streams in which the recipients participate. Some capability methods may contribute to all value streams. An organization unit also must hold accountable each of the services that are engaged by its capability methods.

The operational structure of an agile enterprise is based on value streams composed of capability methods. A value stream will typically have unique capability methods that define the high-level operations required to deliver its product or service. These capability methods will engage other capability methods to develop more detail of the value stream. At some level, a capability method that is unique to the value stream will engage a shared capability method, and because the called capability is shared, any capability engaged by that shared capability method is also implicitly shared (even if it is only engaged by the one method).

Service Unit Design Principles

This section will focus on patterns and principles that influence the design of a service unit as a building block of the agile enterprise organization structure. There are a number of factors that affect organizational design. We will explore these in the sections that follow.

Note that we focus on a typical, automated service unit with a full complement of ancillary and supporting capabilities. Some capabilities may, in fact, be implemented as interfaces to legacy applications or engage an individual or team that operates without automation due to the circumstances and nature of their work.

While we have some capabilities (capability methods or capabilities of individuals) that are dedicated to a single value stream, there will also be many capabilities that are shared (or intended to be sharable) and thus are independent of any particular value stream.

There may be some capabilities that are similar in some ways, but are, nevertheless, clearly different capabilities. These may be candidates for limited consolidation in a single organization unit as a service unit group. In other cases, it is inappropriate to consolidate, but there may be value in applying the same capability method specification to be performed in different service units—replication.

In this section, we will consider the factors that go into applying these design alternatives. We will begin by discussion of the appropriate scale of a service unit as an elementary organizational unit. We will then focus on the grouping of service units, both those unique to a value stream, and those that are sharable, and then the factors that define a single service unit. Finally, we will consider the replication and outsourcing of service units.

Service Unit Scale

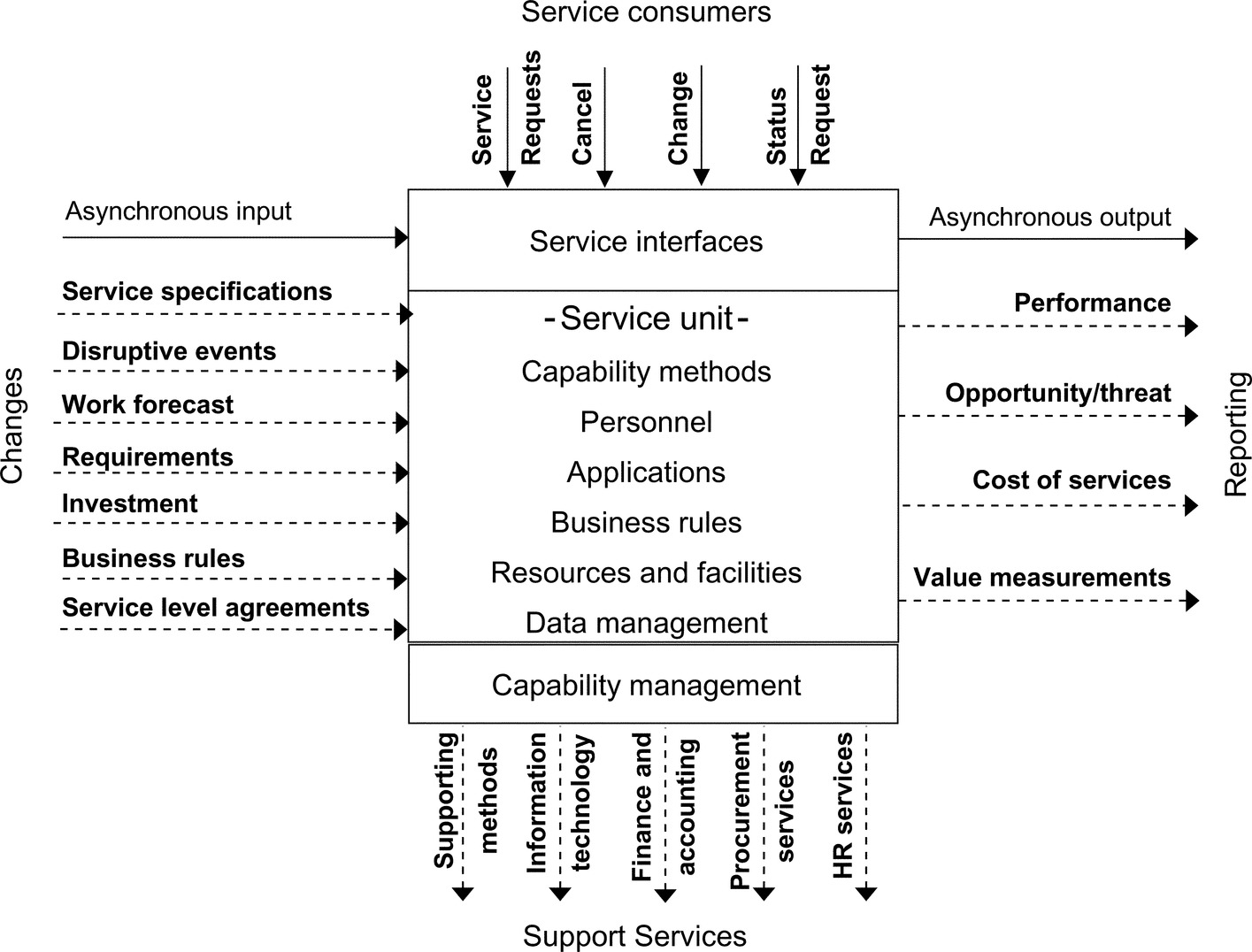

How big is a service unit? A service unit is not limited by span of control since a service unit may have specialized teams. We include in Fig. 10.2 the diagram of service unit interfaces from Chapter 3 to highlight the implied scope of a service unit implementation.

A shared service unit provides a capability that is applied as a service by one or multiple related capability methods. In addition, the service unit has ancillary collaborations for maintenance; problem resolution; and management of personnel, facilities, and resources. Some of these ancillary collaborations may engage other shared services such as expense reporting, purchase requests, and personnel promotions.

It is acceptable that a service unit could include a capability method that is used by its other capability methods, but it should only be engaged by methods of the same service unit. A service unit might also perform methods that have a shared method specification—the specification is shared, but each service unit provides the staffing and resources to apply it. We discuss this further as replication, below.

There will be roles for individuals in a capability method that apply the associated capability. There will be roles for individuals in some of the ancillary services although many of those may be fully automated. There will be opportunities for persons in a service unit to participate in capability methods of other service units such as for submission of an expense report to Accounting, and submission of a purchase request to Procurement. There may be roles for individuals that maintain and adapt the service unit as problems occur or as required by business or technology changes. There may be roles for individuals to ensure security and resolve data management issues. There will be individuals involved in collaborations with recipients of the capability services and those services that are engaged by the service unit methods. There will also be individuals involved in management of resources, including personnel assignments, and availability of consumable and reusable resources.

The staffing of a service unit must consider all of these requirements as well as reserves for personnel absences, vacations, turnover, changing workloads, time for training, and time for participation in other collaborations. People will have different skills that qualify them for different roles. Generally, some personnel must be skilled or trained to participate in multiple roles.

Essentially, a service unit must be big enough to efficiently meet these requirements. Development of the capability hierarchy in the Capability Library (effectively a taxonomy) may define detailed capabilities where each of these could be performed by a single person. These are too fine grained for a service unit and may each be represented by an activity within a capability method. On the other hand, a capability method of one role might be performed by a person from a large team for capability methods that merit a service unit.

Those fine-grained capability methods that do not merit the scale of a service unit should be brought together as alternative methods of a more general capability. If they are quite different, then they should be part of a service unit group where they share the service unit group management and supports.

A Service Unit Group

We will first consider a service unit group before we consider a service unit because the criteria are less restrictive. We will then consider the additional criteria that would qualify a service unit. A service unit group is the placing of multiple service units under the same management primarily for coordination or economies of scale, and for sharing of ancillary activities. These service units are not sufficiently the same to be fully consolidated into a single service unit, discussed later. The following are factors to be considered for formation of a service unit group.

Minimum scale. It may be necessary to form a service unit group to achieve minimum service unit scale as discussed earlier. While there are still separate service units, they can achieve the scale requirements through group economies of scale, discussed below.

Economies of scale. Economies of scale can come from better utilization of resources, technology, database management, and sharing of ancillary and management activities. A service unit group need not achieve all of these economies of scale.

Resources. The obvious economy of scale comes from pooling resources assuming the service units have similar resource requirements. Resource sharing may include personnel, equipment, facilities, and consumable or reusable resources. The personnel can be pooled, and workloads can be balanced to reduce the total staffing requirements. Scheduling of pooled equipment and facilities can improve utilization thus reducing the total requirements. A minimum inventory of resources can be less than the sum of the minimums that would be required by the individual service units.

Technology. Similar capabilities will involve similar technologies. Expertise in the technologies can be shared, so higher levels of expertise can be developed and maintained. This expertise can foster innovation in the implementations of the participating service units.

Databases. Licensing and support for a shared database should cost less when compared to separate databases for each service unit.

Ancillary activities. The service unit group can provide or consolidate ancillary services and administrative functions for economies of scale including implementation of design changes and policy compliance.

Complementary service units. Certain service units may participate concurrently or in sequence in a value stream. There may be opportunities for improved coordination in the scheduling of operations or the continuity of personnel as a unit of production flows from one service unit to the next.

Complementary work products. The capabilities of certain service units may be complementary such that they both participate in the same value stream to produce deliverables that will later be combined. There may be efficiencies or qualities to be realized through collaboration on corresponding units of work.

Degree of data sharing. As members of the same service group, service units may share a database so that they can share data directly rather that exchange messages to access shared data or coordinate updates.

Level of support. Where a service unit requires a critical level of support for reliable operation, it is possible that the supporting service unit might be brought together with the supported service unit for closer coordination. However, the supporting service unit should only be engaged within the service unit group, so it does not have a conflict of interest between serving the group and serving an outside recipient.

Service Unit Consolidation

A particular goal of the agile enterprise architecture is to share capabilities as services, whereas traditional organizations tend to duplicate capabilities in LOB silos. In the agile enterprise, all capability implementations will be incorporated in service units. Service unit consolidation brings together the otherwise redundant service units.

The following sections describe factors that suggest the consolidation of otherwise separate capability implementations.

One capability. The consolidated service unit should represent the implementation of one capability. This may require that the service unit be described as providing a more general capability than some or all of the consolidated service units. Not all of the consolidated service units need to bring all of the shared capability methods.

The capability implementations being consolidated may each represent a particular application of the capability due to the context in which they are being used, and it may be appropriate to include some or all of those applications as capability services within the service unit. However, as much as practical, these applications should be generalized so that they can provide the same services in multiple value streams.

Additional economies of scale. The consolidation of service units will be expected to improve economies of scale in the categories discussed for service unit groups, earlier. If greater economies of scale are not achievable, then the implementations may not represent a single capability.

Consistency of implementation. It should be possible to reconcile different method implementations that have corresponding inputs and outputs. Consistency leads to greater agility by enabling changes in business and technology as well as improvements to be resolved once and monitored for compliance. It reduces the cost of implementation, maintenance, and adaptation.

Note that a shared service does not necessarily operate in an identical fashion for every user of that service. The value measurements of activities may be different, some activities may be performed more or less frequently, and the activities may be performed according to different product specifications. Consequently, a shared capability must produce a deliverable appropriate to each value stream it supports.

Consolidation of control. A shared service can be in important mechanism to ensure the consistent and reliable implementation of policies and controls. A service unit may be important for separation of control from the collaboration being controlled, and it consolidates the control if it is required in multiple value streams.

Separation Factors

It is not always appropriate to consolidate capability implementations (or service units) into a single service unit or a service unit group. The following sections describe factors that suggest that consolidation is not appropriate, and the separation requirement may suggest that service units should be in separate branches of the organization hierarchy.

Separation from service recipients. The level at which a shared service unit and a recipient of its services has the same management must be the same level of reporting or higher for all of the recipients of the shared service. This is to ensure that the shared service unit is encouraged to treat all of the recipients of its service equally, or at least as appropriate to enterprise optimization.

Close affiliation of the service unit with some recipients can be a problem, particularly if the shared service is created from a segment of an existing organization and remains under the same management. Other service units that are expected to use the shared service are likely to believe that they are receiving lesser quality of service due to management priorities and personal relationships, even if the joint manager does not exercise such influence. There may also be a tendency to tap some of the personnel for work of the previous organization.

Different value chain stages. Value chain stages are each focused on creation of value for the end customer, but in different ways that tend to begin at different times in the end-product life-cycle. Value chain stages are significantly independent in purpose, technology, and skills. As a result, each value chain stage will have distinct value streams and will have different capabilities. See the discussion of a product life-cycle in Chapter 9.

While different stages come into play at different points in the end-product life-cycle, they each continue to impact the end-product throughout its life-cycle. As the product develops through its life-cycle, each stage, in turn, will become dominant, and the previous stages will continue to support adjustments to the product life-cycle for new insights and developments.

Service priority. Services that support production operations or provide customer support generally have a high response-time priority and require immediate attention. These should not be consolidated with services that have longer-term efforts.

Demands for immediate action will often interrupt and disrupt the long-term efforts, and performance metrics will be significantly different.

For example, product development services should not be on call for customer support services even though they may have the required skills and knowledge.

Service delivery locations. Some service units and the collaborations they engage will involve direct contact with customers, physical resources, communities of users, or business partners in different geographical areas, so it is not effective to consolidate these capabilities. It may be important to perform the same services in different countries in a way that is more culturally sensitive or that observes data export regulations. Some services may be distributed to different time zones to utilize daytime work hours while providing around the clock services as for customer service. At the same time, with the Internet and collaboration services, colocation of personnel may be unnecessary.

These geographic circumstances can be addressed in three alternative ways: (1) a distinct service unit is located in each area, possibly replicating the capability method(s), (2) individual service personnel work remotely from a central service unit operation, or (3) a single service unit has operations that are in multiple locations. In all cases, there should be consistent service interfaces.

Where there are distinct service units in different locations, the implementations might not be the same in all locations. This might be a function of differences in infrastructure, culture, regulations, or resource availability. These differences might be addressed with a shared capability method that engages specialized, shared methods depending on the geographical domain.

If there are strong differences among the various locations, it is likely that a decentralized organization of separate service units is necessary. These services still may be brought together in groups based on their geographical proximity. At the same time, these services may utilize centralized, shared services that achieve economies of scale and consistency in certain aspects of their operations. This model is typical of some retail operations.

Where the activities are primarily individual employee activities, there could be a single service operation that manages and coordinates the field activities, but the field personnel work remotely, interacting with the service applications for support, assignments, and data entry. This is typical of sales operations, where people spend most of their time visiting customers.

Some service units may simply operate with employees who participate remotely from home or client sites, thus avoiding the need to relocate new employees and making assignments to employees based on their proximity to clients.

Finally, a single service unit may have distributed operations so that the service users make requests of a single service and the service determines where the activities are performed. This could be a model for an engineering service where different specialists are located in different operating sites. For a service that delivers a complex product, various aspects of product development or production might be located in different countries, to optimize the use of expertise and variations in levels of compensation.

Separation of duties. Separation of duties is generally required to offset personal conflicts of interest and prevent inappropriate transfer of assets or disbursement of funds including fraud or embezzlement. Typical applications are expense claims, vendor selection, payment of invoices, hiring, and promotions.

It is appropriate to separate service units that implement critical controls from the service units to be controlled. This avoids privilege for certain people or organizations and ensures that management policies and controls can be quickly, reliably, and uniformly enforced. This separation is evident in the separation of accounting, human resources, and procurement services from the organizations that they support.

For example, funding is controlled by the accounting organization, and business units must establish budgets and obtain disbursements through accounting services. Generally, accepted accounting practices define requirements for separation of duties for financial controls.

Similar services might be implemented for such activities as customer quote preparation, application of government regulations, or allocation of expensive resources.

Separation of duties may also be needed where there are competing objectives. For example, it is appropriate to separate inspection operations from the manufacturing production organization or testing services from a product development organization. This also applies where critical records must be maintained or valuable assets could be at risk.

Incompatible culture. Business culture is a rather subjective quality. It is a product of shared values and working relationships and methods. Consolidated service units may provide the same capabilities, but they may bring different approaches, priorities, roles, and expectations. It may not be possible to clearly identify the culture of a service unit, but there are factors to consider.

For example, the methods and the roles of participants as well as the stature associated with certain roles are relevant. If these are significantly different in the service units under consideration, it is very possible that there will be a lack of harmony in the consolidated service unit. The consequences may be disputes over responsibilities, poor quality work, significantly low productivity of some workers, and increased turnover. There may be similar problems up the management chain, but the most severe discord will occur among people doing the actual work.

Different value priorities. The services brought together in an organization hierarchy should have compatible measures of performance. Two different service units are not expected to have the same service objectives, but the metrics relating to quality, duration, methods, resource management, and responsiveness to users should be compatible, particularly at lower levels in the hierarchy.

Replicated Service Units

Where the same capability is provided in multiple locations, it is important to use the same method specifications to enable advances, new business opportunities, and compliance with policies and regulations to be implemented quickly, and without redundant transformation efforts. This will require collaboration among the multiple sites to reconcile any relevant differences.

The following factors should be considered.

Increased costs. The replicated service units will not realize the economies of scale that could be achieved by a single service unit. This may be reflected not only in costs but also in an inability to respond to changes in demand or employee absences and turnover.

Essentially, the benefits of replication must offset these costs.

Multiple transitions. Changes in technology or business requirements must be rolled out to multiple sites, so there will be time periods when not all of the sites are operating with the same methods. This may cause some confusion and coordination problems.

Redundancy. Multiple implementations of a capability will eliminate a single point of failure assuming that the implementations really are independent implementations, and when one fails, the consumers of that implementation can switch to the other.

Barrier to innovation. The requirement for all sites to have the same processes is a barrier to innovation because an innovator must get all of the sites to agree to the innovation.

Outsourcing of Service Units

Outsourcing can provide greater economies of scale and relieve management of dealing with specialized services, particularly when there are complex or international regulations involved.

Interfaces. Interfaces for outsourcing may occur at various levels for service units as branches of an organization hierarchy or value stream. In either case, the impact on shared services must be considered. The capabilities to be outsourced may be shared with other organizations or value streams, and the outsourced organization or value stream(s) may depend on service units that are provided by other organizations or value streams. These dependencies should be minimized since they will require adaptation of the outsource provider and will require continued attention. VDM modeling will be a valuable source of information on these relationships.

Core competencies. Outsourcing should not occur with services that are core to the operation of the business or represent competencies that are a basis for current or future competitive advantage.

Relationship management. The relationship with an outsourcing provider must be “owned” by a manager within the client enterprise so that there is a single point of contact for negotiations and contract enforcement. The management of the contractual relationship should be in the procurement organization, but management of the operational relationships should be assigned to a manager positioned where the associated service unit(s) would be if they were internal. The primary responsibility is to ensure that the needs of the internal users are met with appropriate cost, quality, and timeliness.

Service level agreements. As with any service unit, outsourced services must have clear service agreements covering level of service, clearly specified service interfaces, management of master data, and sharing of data managed by other service units. The outsourced services must deliver appropriate value measurements along with deliverables.

Here the owning manager is directly responsible for compliance with the service agreements and service interfaces. The procurement organization is responsible for the contractual relationship.

Adaptors. There will be a need for adaptation and thus some negotiation of service interfaces provided and used by the outsourcing provider. Additional issues may arise in the future as the provider introduces operational improvements or changes for regulatory compliance. Changes that impact an interface should be addressed by collaboration at an enterprise-level, as with other transformation initiatives, including representatives of service consumers, the outsourcing owner, and contract manager.

Management Hierarchy

In an agile enterprise, organization units in the management hierarchy are responsible for managing resources for the delivery of services. The leaves of the hierarchy are where the work of capabilities is actually done. The hierarchy brings together service units that have similar capabilities and objectives. This aggregation of organization units with similar capabilities facilitates the development of expertise, economies of scale, alignment of incentives, and adaptation to changing business requirements.

From an organizational perspective, we focus on service units where each service unit is a cluster of services for the same capability. A service unit group is an organizational grouping of related service units, at the next level up the management hierarchy, for economies of scale such as sharing of a workforce, equipment, and special skills. The management hierarchy should reflect degrees of affinity of capabilities from the consolidation of capabilities in service units with successively lesser degrees of affinity going up the management chain. Note that the delegation hierarchy of services engaging other services is not the same as the management hierarchy.

The top-level management hierarchy brings a focus on the overall enterprise for management of the business, optimization of operations, and response to business threats and opportunities as well as advances in technology.

The management hierarchy is enhanced for an agile enterprise (1) to support agility and (2) to support governance, management, and optimization of a dynamic enterprise.

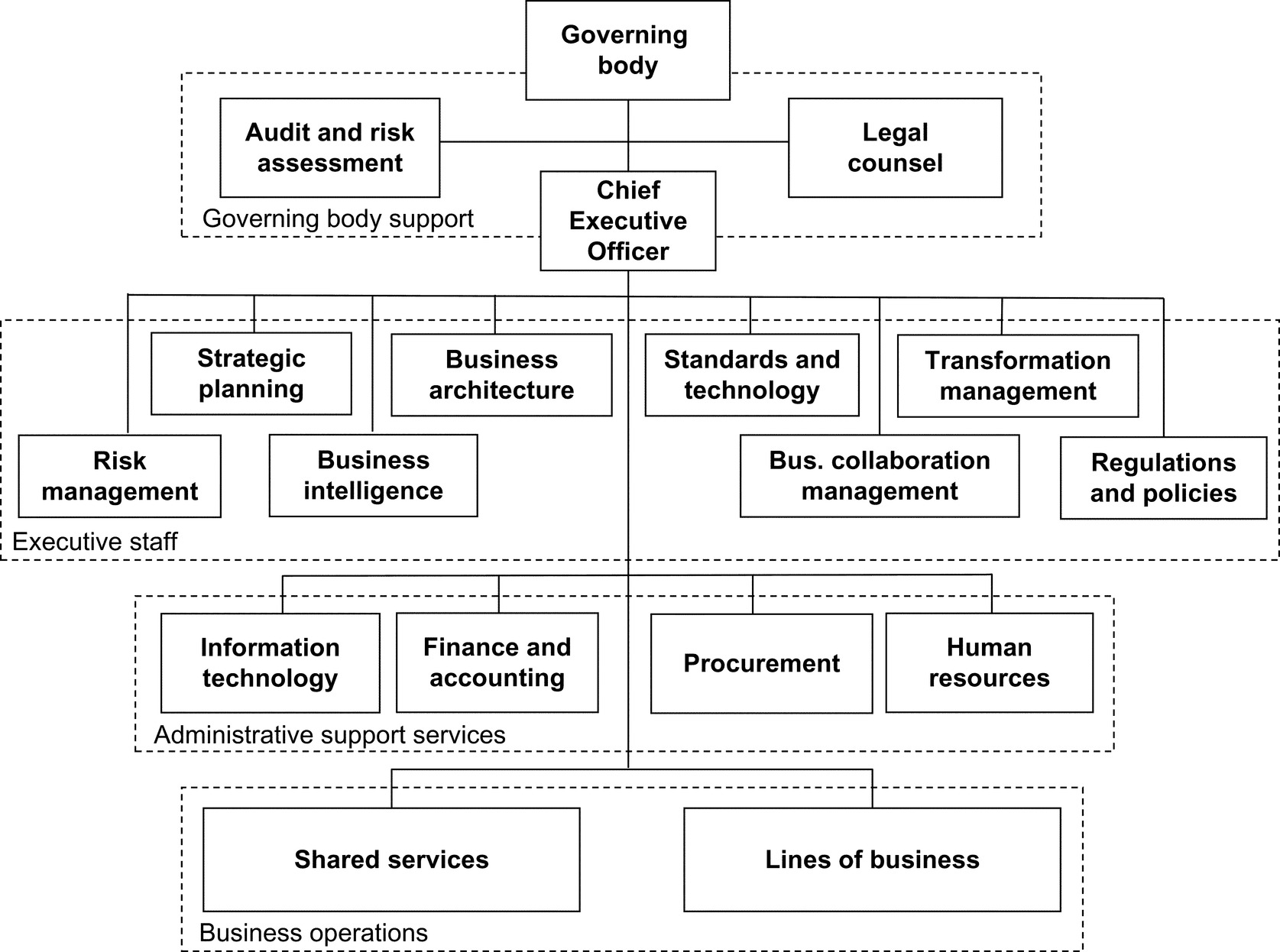

In this section, we will examine the executive-level management structure under the topics of governing body support, executive staff, administrative support organizations, and business operations. The overall structure is depicted in Fig. 10.3.

Governing Body Support

The board of directors or other governing body should be able to see the same information that is available to top management, but generally, access will be selective, based on current concerns. We will examine the responsibilities of the governing body in greater detail in Chapter 11. Two responsibilities should report directly to the governing body since they could have a conflict of interest with the CEO: (1) Audit and Risk Assessment and (2) Legal Counsel.

Audit and Risk Assessment

These activities require an assessment of how the business works with consideration of the integrity of operations and record-keeping and the level of risk undertaken by management decisions and business operations.

Risk is a topic of considerable concern given the increased risks associated with government regulations, potential liabilities associated with product defects, and breaches of security. Shared services have the potential to increase risks through broader exposure of systems and the creation of consolidated service units that could be single points of failure. Risk assessment goes beyond consideration of deviations from expressed operating requirements and considers business circumstances, practices, events, trends, and enterprise design that create notable risks to the enterprise. Understanding and eliminating, mitigating, or deciding to tolerate risks is an important concern for executive management as well as the governing body.

Audit is combined with risk assessment because both are concerned with identifying risks. Audits generally focus on compliance with record-keeping and compliance with policies, regulations, and standard practices. This group may not perform all levels of audit, such as security and recoverability of systems, but it should ensure that such audits are objectively performed.

Audits and risk assessments are not intended to resolve risks or fix problems of accountability and control, but they should assess the risk mitigation, and the effective level of risk, and they should identify audit problems and evaluate the resolutions. This separation of duties to evaluate from duties to resolve is important so that those assessing the risks or identification of problems do not become invested in the solutions.

There are always risks. The purpose of this service unit is to ensure that executive management and the governing body, as well as other stakeholders, are aware of the risks and that they are at least mitigated to an acceptable level.

The following are examples for the scope of risk assessment:

• Social, political, and economic disruptions

• Overlooked threats, opportunities, and loss of market share

• Investments and money management

• Single points of failure that could cripple the business

• Loss of enterprise assets

• Exposure of systems or confidential data

• Failure of programs or projects

• Regulations and legal liability

• Risk to reputation

• Failure to meet or improve upon industry best practices

• Employee working conditions

• Supplier performance

Information security risks are discussed in Chapter 7, and risks of business change are discussed in Chapter 9.

The business design using VDM modeling provides a valuable context for consideration of risks and audits. Value streams and service units identify where work is done, resources are consumed, policies should be enforced, and decisions are made along with the organizations responsible. The flow of control and deliverables identify the consequences of failures and thus the scope of risk and effects of efforts toward mitigation.

Each risk situation should be documented along with the level of risk. Resulting corrective action or mitigation efforts should be documented and followed by reassessment to ensure that an acceptable level of risk is achieved.

Operational risk management is part of the business architecture unit since it is closely related to business design. Mitigation of other risks is the primary responsibility of the organization units in which the risks arise.

Legal Counsel

Legal counsel must deal with a variety of issues that we will not elaborate here. However, some companies fail to recognize the importance of intellectual property to their competitive position. Employees should be encouraged to develop and propose patentable ideas. Some internal techniques may be subject to trade secret protection. Product names require trademark protection, and copyright or possible copyright infringement may be important for some publications. These are likely to be of increased importance in an environment where innovation and adaptation are becoming increasingly important. Legal counsel must also identify various sources of liability and suggest means of mitigation.

Executive Staff

Executive staff services provide support to top management and the governing body by providing information, development of detailed analyses and plans, facilitating collaboration and coordination, developing and applying policies, and providing oversight of performance and transformation. Each of these may be viewed as a service unit, and some of the services may involve participants from other organizations, or they may engage shared services of other organizations. These organizations provide services to top management or on behalf of top management, and often collaborate with participants of other organizations to solve problems or develop plans.

Executive staff services must report to the CEO or a person reporting directly to the CEO to ensure that they function with an enterprise-wide perspective. The executive staff services provide the mechanisms for governance and transformation of the enterprise. The services are under the CEO but should provide support to the governing body as well.

Strategic Planning Unit

Strategic planning is the responsibility of top management, but it must be supported by a team that facilitates the discussion and pulls together the detail of an enterprise strategic plan. See Chapter 9 for details on a strategic planning framework and coordination of transformation activities.

Strategic planning has new insights and supports from the other executive staffs as well as employee initiatives to identify challenges and opportunities, using VDM models for business conceptual design and context for assessment, design, and implementation of initiatives.

Business Intelligence Unit

Business intelligence has responsibility for analytics, data warehouse, measurements, and knowledge management. See Chapter 6 for more on these data management services.

Business intelligence also has responsibility for support of the interest groups with such facilities as email distribution lists, webinars, and group web pages.

The goal is to provide information for analysis, planning, process improvement, and risk analysis for top management as well as others involved in solving problems; optimizing performance; and assessing threats, opportunities, and transformation proposals.

Business Architecture Unit

Business architecture is responsible for defining the architectural characteristics of the enterprise and for development of the detailed, conceptual business design based on top management requirements.

Business architecture will develop and maintain in-depth VDM models of the current business design with associated value measurements for performance and change evaluation. It will develop to-be models to validate innovations and strategic initiatives and will develop transitional phase conceptual models that represent a top management consensus to drive and harmonize transformation efforts.

Business architecture provides the VDM models as the business context of measurements presented in executive dashboards.

Risk Management Unit

Risk management is a major business concern. Risk assessment, discussed earlier, has a primary responsibility for identification of risk factors and determination of the severity of the risk. Risk management is responsible for supporting the enterprise management to identify and manage risks with efforts to avoid or mitigate risks. This requires close work with business architecture to design the business to minimize risk and to introduce measures to mitigate risk such as rapid response to resolve a disruption of operations.

While VDM modeling provides a context for consideration of risks, not all risks occur in that context. Some external risks may be mitigated by business design and rapid response. Risk is a major business concern and requires close coordination of business architecture with risk management.

Regulations and Policies Unit

Note the discussion of regulations and policies in Chapter 5. Regulations must be interpreted in the context of the particular business and expressed as policies. Additional policies must be defined to address concerns of the governing body, to mitigate risks, and to define operating requirements.

VDM provides an understanding of the business design to identify where compliance is a concern, determine the mechanisms for reliable application of the policies to ensure compliance, and avoid redundant enforcement efforts.

Regulations must be traceable to policies and policies must be traceable to the activities where they are to be applied as discussed in Chapter 9.

Standards and Technology Unit

The role of the standards and technology unit is to lead efforts to develop and adopt relevant industry standards and emerging technologies for product design and business operations, particularly information technology. Furthermore, this unit must coordinate efforts to identify and evaluate the business impact of new standards and technologies.

Standards participation. The standards and technology unit should develop recommendations and manage budget for representation of the enterprise in industry standards organizations and particular standards development efforts. This is a source of insights on interests of competitors and potential areas of competition as well as technology trends. Standards and technologies are particularly important for information systems where there is continuous industry change.

Adoption of standards. The standards and technology unit should lead internal collaborations to evaluate the business impact of adopting specific standards and technologies and to develop proposals for implementation.

Information technology product selection. Standards and technology should be the leader in the development of the enterprise logical data model, and the owner of on-going maintenance and compliance enforcement, and it should lead collaborations on the selection of information technology products. The objective is to (1) ensure compatibility for exchange of information between service units; (2) ensure compatibility of data for cross-enterprise access and integration of information; and (3) promote economies of scale in information technology of service units, information system development, and systems maintenance by avoiding unnecessary technology diversity.

Standards compliance. Standards and technology should review product designs, system designs, and other business practices to assess compliance with adopted standards and technologies.

The IT services organization has primary responsibility for recommending standards and preferred products. The standards and technology unit is responsible for determining which standards and product preferences are appropriate from an enterprise perspective. Representatives from the various departments of the enterprise must collaborate in these decisions as well as decisions regarding deviations from the standards and preferred products.

Product acquisition and application development processes must include review by the standards and technology service unit, and deviations from standards should be authorized only if there is a clear business case for the deviation. This consideration must reflect the likelihood that the loss of economies of scale experienced by the IT service units will persist many years into the future, whereas the benefits of using a noncompliant solution may be only temporary.

Transformation Management Unit

The transformation management unit is responsible for coordination of transformation initiatives starting with the sense and respond directory to communicate notices of threats and opportunities for further action as well as program and project management to coordinate the multiple transformation initiatives, reconcile overlaps, and facilitate collaboration. See transformation management in Chapter 9 for more details.

Program and project management. Program and project management (PPM) supports the coordination of enterprise changes and the planning and tracking of transformation efforts. The PPM team should provide support for project planning and progress reporting independent of the individual project teams. Project responsibilities should be assigned to organization units that have responsibility for transformations within their areas of responsibility.

Identification, planning, and reporting of status and milestones are supported by the sense and respond directory that is managed by the PPM team. PPM will ensure that an observation that may represent a threat or opportunity will be brought to the attention of an appropriate person or process, and that the issues will be resolved by either a decision of no action or the initiation of a process for appropriate response. PPM will be responsible for collaboration and coordination among the various related efforts. The PPM team must also identify potential synergy or conflicts between independent efforts and facilitate coordination and collaboration to reconcile differences and optimize results.

For example, suppose there is an insurance enterprise initiative to consolidate four claims processing activities into one shared service unit to achieve economies of scale. A new service unit will be formed and positioned in the management hierarchy to be relatively independent of the organizations currently managing claims processing. The requirements for the new service unit, organizational implications, the impact on the related service units and lines of business, and the expected investment and return on investment are developed by business architecture in collaboration with affected organizations. Each of the four organizations that have processed claims in the past is expected to use the shared service unit. The IT organization is required to adapt, acquire, or develop the automated business processes and application software for the consolidated service unit.

A steering committee (collaboration) chaired by PPM might be formed with representatives of the affected organizations, including IT, business architecture, and BCM. PPM is responsible for a program plan that coordinates project plans, including an application development project and an organization transformation project. PPM, along with the steering committee, is responsible for requirements change control. PPM must coordinate, directly or indirectly, issues of training, cultural change, alignment of goals and incentives, BCM, and standards compliance. A community of affected personnel might be formed to provide a forum for discussion and resolution of personnel issues and concerns.

As the enterprise adopts case management technology, much of this activity can be coordinated with a case management (CMMN) system and much of the tracking, supporting, and reporting can be automated.

Business Collaboration Management

The purpose of the BCM unit is to provide a center of expertise and collaborate in the formation, recognition, automation, integration, and participation in appropriate collaborations. BCM must assist in the definition and automation of business processes, case management (collaboration) specifications, and decision management notation (DMN) for expression of rules. The BCM unit will provide support for both transformation implementation and incremental improvement. Note that while business architecture is focused on collaborations at a conceptual level, BCM is focused on the increased detail of collaborations at an operational level.

Administrative Support Organizations

The traditional administrative support services are finance and accounting, procurement, human resource management, and information technology. These already separate management of their shared services from the product value streams that they support.

Administrative support services essentially provide separation of control, economies of scale, and specialized capabilities that are more effective if managed independently.

These support services also provide shared services to each other, so the management of these shared services is also separated from the recipients of the services.

Difficulty occurs when a support services organization needs to use their own shared service units. While this violates the separate management principle, this is mitigated by the fact that the support service performance is measured by its level of service to other organizations, so there is a greater risk that it is the internal recipients of these shared service units that will suffer from neglect rather than that the shared service units will be affected by undue influence.

These services may be engaged through participation in collaborations with supported organizations, through receipt of requests for services, or in response to events that require their attention.

In the following paragraphs, we will focus on services from each of these organizations that require particular attention for the agile enterprise.

Human Resource Management

Employee orientation. To support an agile, value-driven enterprise, HRM should focus particular attention on the impact of service unit autonomy, the challenges of continuous change, and the need for appropriate incentives. This may involve the services of industrial psychologists.

Temporary and contract personnel. The agile enterprise will have changing service unit workloads adapting to new business challenges and opportunities. HRM will need to support arrangements for temporary and contract employees with short notice. Procurement may need to provide flexible contracts with personnel contractors.

Finance and Accounting

Value measurements. Value measurements are a critical part of assessing performance of the enterprise, particularly for accountability and governance. It is appropriate that the capture and accuracy of these measurements be the responsibility of accounting.

Internal billing. Every service should bill the recipients of its services for the cost of its services, including overhead and the costs of services it uses. Accounting must manage the internal billing system, including the allocation of the overhead cost for unit of production, for value delivery analysis.

Adaptive budgets. Each service unit should have a budget. Particularly at this level of granularity, it is not appropriate to lock in a budget for a year. There is a need to make budgeting more adaptive to changing variable costs and to provide more timely authorizations and effective notations on variances.

Procurement

Outsourcing. Once outsourcing is determined appropriate, procurement is responsible for outsourcing contracts, including negotiations and contract enforcement. The contract manager must work closely with the outsourcing service manager/owner that has oversight and problem resolution responsibility for the outsourced services and their interfaces with other internal services based on VDM.

Value contributions. The impact of the cost, quality, and timeliness of purchasing service units has an impact on both product development and production operations. Delays in purchases can affect the timely introduction of new products and their success in the marketplace.

The cost, quality, and timeliness and other value contributions of supplier products and services have a direct impact on production value streams. Procurement is responsible for the values delivered by suppliers and for enforcing their compliance with level of service agreements.

Virtual enterprise. Procurement should be prepared to analyze and negotiate relationships with potential partnerships if a virtual enterprise strategy is adopted.

Information Technology

Information technology contributes to a number of agile enterprise capabilities, outlined below. For more detail, see each chapter with a description of supporting information technology.

Analytics. Information technology must support the analytics tools, databases, and data capture facilities.

Knowledge management. IT must provide the systems for knowledge management as discussed in Chapter 6.

Dashboards. Dashboards represent a management tool to be supported by IT services. Dashboards must be linked to events and measurements in the operation of the business.

Infrastructure management. IT is responsible for management and operation of the technical infrastructure, including computers, communications, and data storage as well as email, notification service, security facilities, business process systems, and case management systems.

Optimal use of information technology. The IT organization, like other service groups, is responsible for optimization of its operations. In addition, it is responsible for bringing new technology into the enterprise for applications where there is appropriate business value.

Service unit automation. IT service units support automation of business service units and other collaborations. This includes development of automated business processes, development of supporting computer applications, implementation of commercial software, transformation of legacy systems, systems integration, problem resolution, and technical support.

Strategic planning. The CIO should be a member of the strategic planning team, the same as other enterprise executives. The CIO brings a perspective on advances in technology and the application of technology to optimize the operation of the enterprise.

Business architecture. Business architecture requires technical support for a number of its responsibilities. In particular, it requires support for VDM and other modeling tools, capture of value measurements for VDM, and transformation planning. IT personnel are needed, along with BCM, to translate the VDM conceptual models to operational system models to implement the details of the systems and processes.

Enterprise intelligence. IT supports development of the enterprise logical data model, knowledge management facilities, analytics tools, and so on. See the data management services in Chapter 6.

Enterprise transformation. IT must provide the technical capability to develop and deploy detailed business processes and applications; integrate service units, applications, and business rules; transform legacy applications; and implement appropriate security facilities.

Standards and technology. IT provides the primary input for defining and implementing information systems standards and technology selections driven by a need to minimize diversity and achieve economies of scale in IT service units.

Business Operations

The business operations organizational units manage the service units that deliver the enterprise products and services. There are two basic categories: lines of business and shared services.

Lines of Business

An enterprise will have one or more LOBs. An LOB delivers products or services to customers.

Product life-cycle management. A line of business is responsible for management of the life-cycle for each product. See the example life-cycle in Chapter 9. The LOB will manage the top-level collaboration(s) that drive the life-cycle stages and directly or indirectly engage shared services to do the detailed work. As the product evolves through improvements and adaptations, capabilities of the life-cycle stages will be involved in varying degrees in the transformations.

LOB value stream management. Each LOB manages value streams for its products or services. At the top-level, a value stream will have service units that are unique to the LOB. These service units will engage other service units that directly or indirectly engage shared services to perform the detailed work.

Shared Services

In the agile enterprise, much, if not most of the actual work of the LOBs should be delegated to shared services.

Each shared service unit, directly or indirectly, must report to an organization unit that is organizationally higher than all organization units that are recipients of its services. This is to ensure that one value stream does not have undue influence over the operation or optimization of the shared service. This basic principle is a key factor in the design of the management hierarchy for an agile enterprise. Consequently, there is a fundamental separation of LOB organizations from shared service organizations.

We have already identified shared services for the business administration services: finance and accounting, human resource management, procurement, and information technology. This leaves the remaining shared services that include more direct support of LOB operations.

We have partitioned these remaining support services using value chain stages to identify lifecycle stages. Most of the value chains in an industry will be very similar, and thus it should be possible to define a value chain that reasonably supports all of the product life-cycles of the enterprise. Each of the value chain stages involve different capabilities and different value streams and thus are a basis for grouping the shared services.

A shared services organization will support multiple value streams that are relevant to its participation at various product life-cycle stages. For example, the product development stage will at least support a value stream for product development and another for product revisions. The primary capabilities of these value streams will be LOB capabilities, so there will be different value streams associated with different LOBs and there may be different value streams for product lines within a LOB. A shared services organization, like the traditional support services, will have service units that support some of its multiple value streams but also like the traditional support services, the performance of the stage is based on contributions to the success of that stage for all products. The value measurements of these value streams contribute to the overall success of each product and the enterprise.

Interorganizational Collaborations

Beyond the stable business organization structure, there are some collaborations that are continuous and others that will occur from time to time to coordinate the efforts of multiple organizations. These collaborations should be visible in the extended organization chart. Some examples follow.

Requestor collaboration. A person requesting a service or initiation of some action may do so by initiating an ad hoc collaboration with one or more persons of the service provider organization. The purpose is to develop a consensus on the proper action.

Peer to peer. A group of peers may come together to solve a problem, develop a proposal, or coordinate efforts among their respective organizations. Such collaborations may grow out of exchanges among members of an interest group (see the discussion of knowledge management in Chapter 6). The group may choose a chair person from among the participants.

Coordination of initiative. A collaboration may be initiated by one organization to engage participation in an interaction by other organizations. This could include coordination of changes in a transformation initiative. In this case, the initiating organization may provide supporting resources and might provide compensation for the time of the participants and other costs incurred by the participating organizations.

Enterprise-level optimization. Optimization of shared services requires enterprise-level leadership in a collaboration to resolve different interests of service providers and service users. The goal is to develop a feasible and optimal solution using VDM to configure and evaluate alternatives based on costs and duration of change and the impact on affected value propositions.

Innovation. Some innovations can be pursued within the scope of a single service unit; however, an innovation with broader impact will require collaboration for refinement with peers representing technical and organizational perspectives. Such collaborations should be encouraged to enable the innovator to develop the idea sufficiently for higher management consideration.

Contract negotiations. Representatives of procurement, affected service units, and supplier representatives may collaborate to arrive at a contract agreement.

Customer relationship management. Sales representatives and various other product experts may collaborate with customer representatives to develop a sales agreement or maintain a customer relationship.

Enterprise Transition

This section provides insight for enterprise transition to the agile enterprise by providing the basis for planning the future organization structure. Changing the organization structure drives changes to the business and helps align the objectives of people with the objectives of the enterprise.

Development of an agile enterprise seldom starts with a blank slate but must deal with the realities of an existing organization. This is a multidimensional transformation. The approach must evolve. The following sections focus on organizational aspects of the Value Delivery Maturity Model discussed in greater detail in Appendix A.

Level 1, Explored and Level 2, Applied

Organizations at level 1, explored, and 2, applied, should focus on consolidations of capabilities to realize business benefit with reasonable return on investment.

For example, multiple claim payments systems of an insurance company or multiple order management systems of a manufacturing company or multiple billing systems of a telecommunications company might be consolidated with redesign to create appropriate capability service units. At least some of these service units should be in anticipation of sharing with future value streams.

These value streams must be built on the agile enterprise information technology infrastructure to support message exchange, notification, and message transformation and should incorporate service unit databases based on the data management architecture of Chapter 6. Message and event exchanges must be based on an enterprise logical data model of at least sufficient scope to specify the messages exchanged for the new value stream(s).

In addition, information technology should implement tools for analytics and knowledge management. A small analytics activity should be established, and support for knowledge management should be implemented as described in Chapter 6. These facilities should be used as soon as possible to gain acceptance and start to show business value.

In most cases, this should result in service units that achieve significant economies of scale through consolidation. Alignment of these service units with the organizational hierarchy should give consideration to the design principles and management hierarchy design factors discussed in this chapter.

Once there are initial stage support service organizations established, these organizations should aspire to increase their shared service units by consolidation of capabilities from LOBs. These should be justified by realization of economies of scale and, in some cases, improved control.

Level 3, Modeled

To achieve level 3, modeled, all production value streams should be modeled, and work should be under way to consolidate capabilities into shared services. Shared services must be organizationally separated from the LOB capabilities they support. This will provide the basis of a plan for further consolidation of capabilities and the transformation of production value streams.

Transformation of value streams should be one at a time, at least initially, to develop the disciplines and skills for transformation. After the first value stream transformation, the second should help drive the consolidation of more capabilities for further economies of scale by sharing service units established for consolidation(s) of level 2 and the first production value stream.

At the same time, establishing a new product through the product life-cycle could be a significant driver for further development of the stage support service organizations and could increase understanding and acceptance of the strategic direction of the enterprise.

As value streams are implemented, they should be measured and the measurements captured in a measurements database. Initially this may be limited to time and cost averages of capability methods, but work should be under way to capture actual measurements at activity levels where the operational activities correspond to deliverable flows of the VDM-level, conceptual activities, so the measurements have meaning in a VDM model context. This will require measured activities to issue events to communicate measurements.

Planning for transformation of administrative support services may be deferred except that compatible service interfaces should be implemented for integration with the transformed value streams. In addition, consideration should be given to outsourcing with appropriate service unit interfaces to be provided by the outsource provider.

Level 4, Measured

At level 4, measured, much of the organization should be transformed, particularly those elements involved in production value streams. The executive support services should be established and should be developing their enterprise leadership roles. Service specifications should be formally defined, and the capture and reporting of performance metrics should be supported by the infrastructure, enabling greater empowerment of service unit managers and their people to pursue improvements. The organization structure should be near to an agile enterprise design.

Measurements should be captured and managed consistent with VDM scenarios to provide a context for the measurements. Information technology must support a dashboard capability and provide user support for key executives with plans to expand to all mid-level managers.

Strategic planning should be supported by enterprise intelligence, business architecture, standards and technology, regulations and policies, and transformation management. Business architecture should maintain current and proposed VDM scenarios and measurements for analysis and planning, including value propositions, for alternative futures. At least one transformation initiative should be supported by specification of transformation phases with VDM. Strategic planning as well as sales forecasts and product planning should be supported by analytics insights on market trends and opportunities. Mechanisms should be in place to encourage innovation and support collaborations for refinement, formal recognition of innovation, and investment.

Level 5, Optimized

At level 5, optimized, the organization structure should be transformed based on the organization design principles and hierarchy factors discussed earlier in this chapter. The agile enterprise organization structure should be in place to support continuous change, optimization, and effective governance. Strategic planning and transformation are continuously active and adapting to threats, opportunities, and changes to the enterprise ecosystem.

Moving On

In the next chapter, we will consider changes in leadership roles.