Chapter 2. A Story in a Single Image

Maria Sharapova defeats Justine Henin 6-4, 6-4 to win the U.S. Open women’s finals match in Arthur Ashe Stadium on September 9, 2006.

ISO 320 f/2.8 1/500 45mm

When I was 18 years old, in my first year of college, I managed to get an appointment at the offices of Newsday.

With a combination of persistence and naïveté, I charmed the secretary of the assistant editor of photography. She was a notoriously cool gatekeeper and no one could get past her, but somehow I did.

I walked into the offices of a man named Kenneth Irby prepared to show him my work. Even before he opened my book, he looked at me and said, “How did you get in here?”

You are ultimately trying to get an idea or an emotion or the story itself out, all the while trying to balance that with the aesthetic of the photo.

It hadn’t been easy; to keep the appointment, I had to convince a friend to drive me from Manhattan to Long Island through a tremendous snowstorm.

I sat there as he looked through my portfolio, which at the time included images of sunsets and my sister. They were pretty pictures, and I had worked for hours in the lab crafting the best fine-art prints I was capable of making.

“I don’t know how you managed to get in here,” he said, closing my portfolio. “You’re no photojournalist. This is not the type of work we do at this newspaper or any newspaper, for that matter.”

It was not what I expected to hear.

“You know what, kid, you might have some promise, but get out of here,” he said, but then added, “If you are really serious about this, send me some clips in a month. Maybe we’ll talk again.”

I was sent flying out of his office, feeling angry and destroyed. And now I was left to ride back home through a snowstorm.

I was still angry three months later when I sent Kenneth Irby some clips from my work at Northwestern University’s college newspaper. I think I stuffed a foot’s worth of prints and clippings into an envelope with a little note, which might not have been as friendly as it should have been.

He wrote me back and we met. My persistence paid off and he became one of my most important mentors.

It also marked the beginning of my understanding of the role of story in photographs.

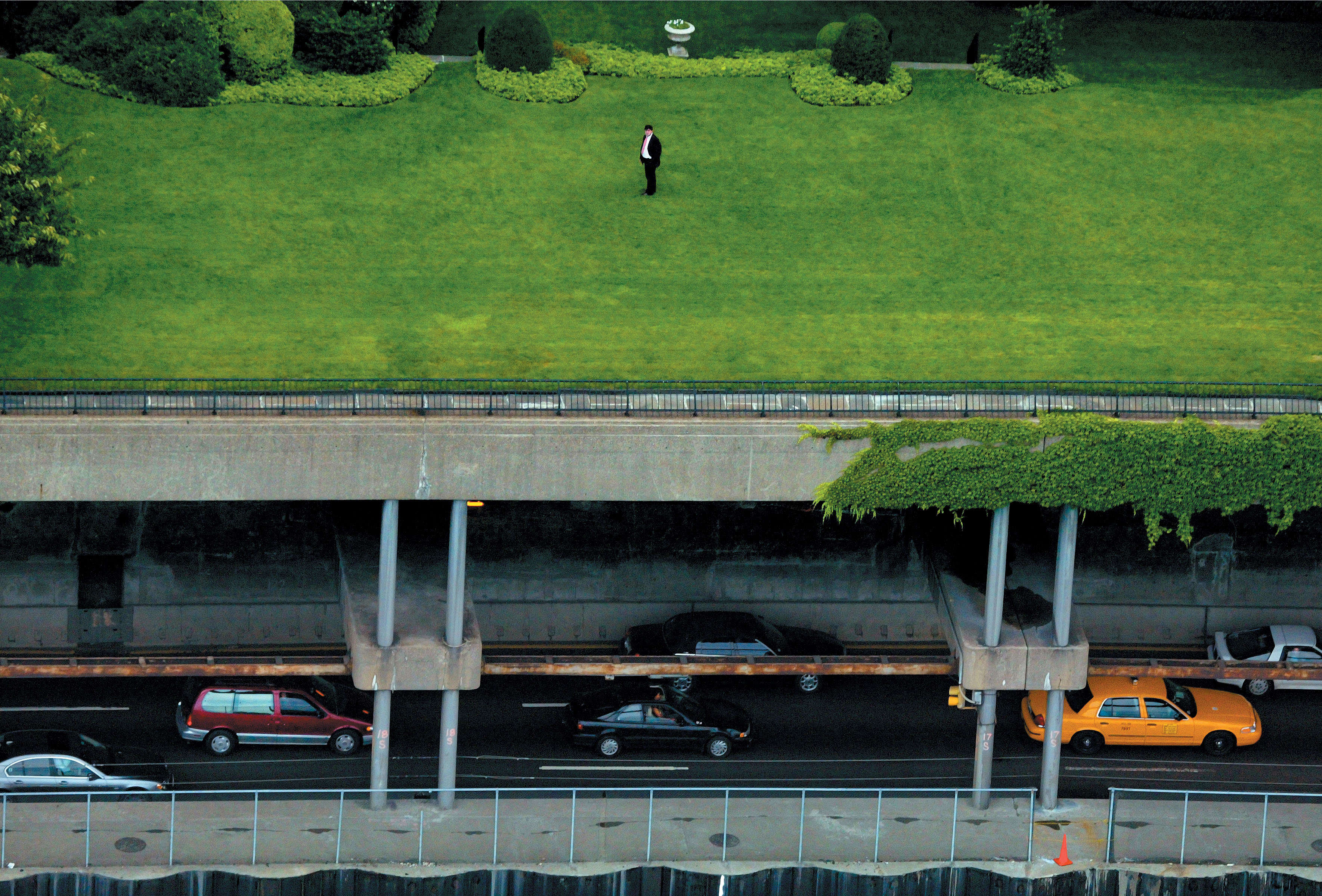

The garden behind 1 Sutton Place South, atop FDR Drive, between East 56th and 57th Streets in New York City.

ISO 400 f/5.6 1/1000 70-200mm

The Importance of Story

As a photographer, whether a photojournalist or a wedding photographer, your goal is to tell the story of the moment, sometimes the entire event in just one image. It’s that one image that a newspaper or magazine is going to use to open the section that communicates what the article is about. It’s the ultimate challenge for a photographer.

The ability to tell a story applies to almost everything, whether it’s for a newspaper, a commercial job, or a journal, or if you are taking photos of your own family. Even if you’re a portrait photographer, story helps to set up everything and touches everything you do.

You are ultimately trying to get an idea or an emotion or the story itself out, all the while trying to balance that with the aesthetic of the photo.

It was explained to me, and I saw it reflected in the photographs that got published at the newspaper: the images that were able to take that 600-, 800-, or 900-word article and visualize it found a home on the page.

The challenge was that you couldn’t just veer off and go astray and photograph random stuff. What you took had to be relevant to the event. It comes from the cold fact that there is a limited amount of space on the page, and the photograph either serves the story or it doesn’t.

When you are making photographs, the reality is that there are hundreds of images out there. So which is the one image that really captures the essence of the event that day? Which shot expresses the mood, the feeling, and the significance of the moment?

“What’s the news value?” is the question you have to ask yourself. What makes this relevant? What makes this worthy of being spoken about or written about, let alone published as a photograph in newspapers around the world? And you have to be mentally on your toes to know that. You can’t just passively float through and take random pictures and hope to capture those moments.

That’s a real challenge, because it doesn’t happen randomly. You’ve got to be connected emotionally and intellectually to what you are covering. And you need a tremendous sense of perspective. The reality is that usually while an event is happening, most people don’t know what the relevance of it is until they’ve had the opportunity to digest it, but by then it’s over.

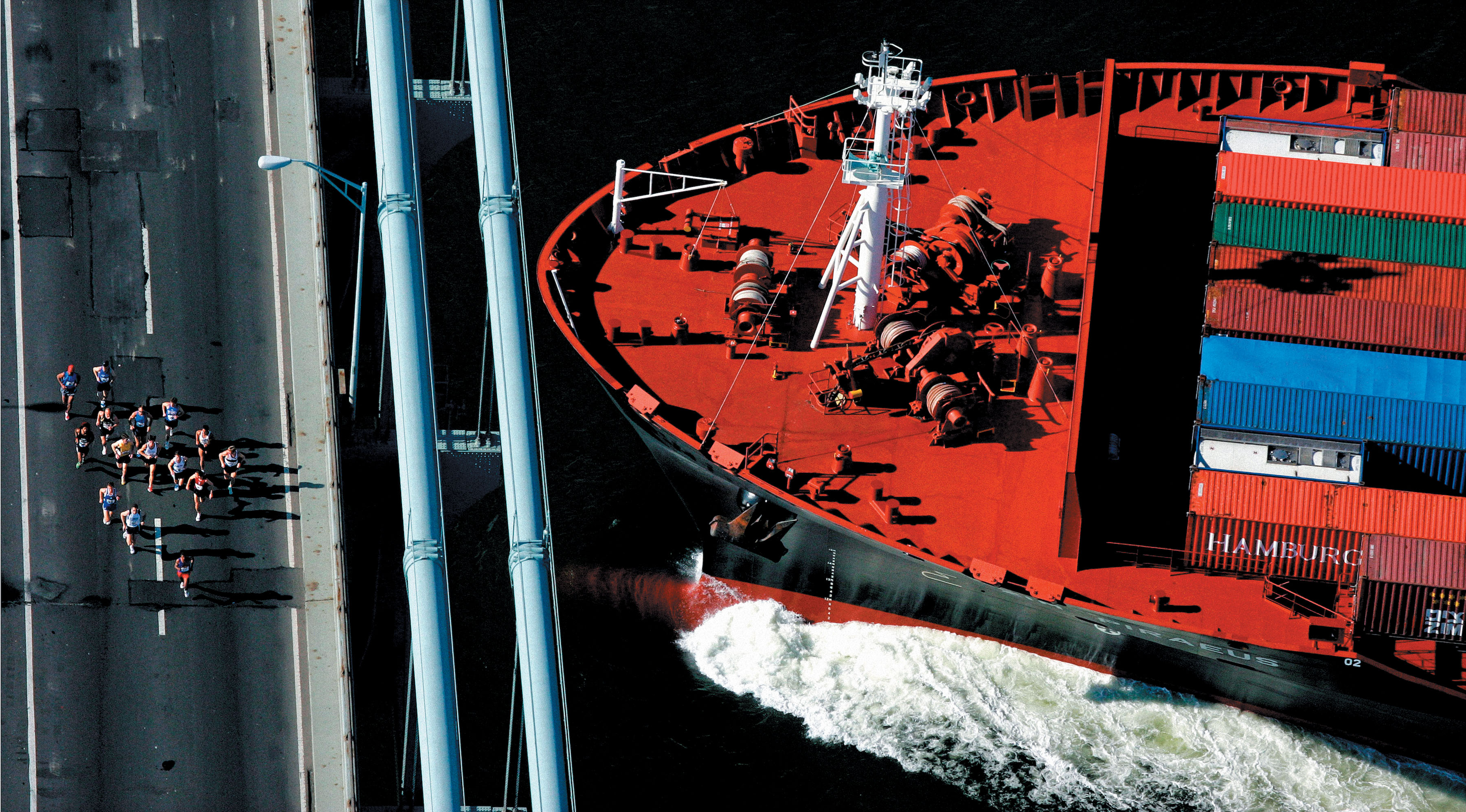

Aerial photograph of the 2004 New York City Marathon.

ISO 400 f/6.3 1/2000 250mm

4-year-old Clara Anisha Brown grasped onto volunteer Chad Meaux as they made their way through the flooded streets of New Orleans after she and her family were rescued from St. Bernard, Louisiana, after 3 days without food and water (August, 2005).

ISO 400 f/4.5 1/250 24mm

The reality is that usually while an event is happening, most people don’t know what the relevance of it is until they’ve had the opportunity to digest it, but by then it’s over.

As the photographer, you are live on the scene, and it’s very difficult to anticipate what this is going to mean ten years from now or even on a simpler level, in tomorrow’s newspaper.

The photograph on the facing page of a volunteer helping rescue a mother and daughter during Katrina helps to illustrate a side of the story of how the disaster helped people overcome, if just for a short period, issues of race.

New Orleans and Louisiana have always been places that have had issues with racism. There has never been a secret about that. If you have ever flown over New Orleans, it’s not uncommon to see the Confederate flag on people’s roofs. And you hear it in the words people say from both sides.

But here you have this little black girl clinging to this white man in a flooded New Orleans. What you don’t see in that shot is that below the waterline are the roofs of this community. This family’s neighborhood, their world, no longer existed. The photograph succeeds in telling an important part of the story of this disaster and the people’s whose lives were changed by it in dramatic and unexpected ways.

There’s a reason why they say that an image is worth a thousand words. It’s actually worth a lot more.

Maria Sharapova defeats Justine Henin 6-4, 6-4 to win the U.S. Open women’s finals match in Arthur Ashe Stadium on September 9, 2006.

ISO 320 f/2.8 1/500 45mm

Story with Context

One of the first things I ever photographed in my teens was the U.S. Open. I found an entrance to sneak into the main court at the time, and I would photograph from the cheap seats. I would stare down at the newspaper photographers and dream of being down there with them.

A decade later, in 2006, I found myself in those very seats, on the ground level, surrounded by the best in sports photography. From that level, it’s great to capture a very tight moment that shows the incredible emotion of a historic win. While that’s an important image to capture, such a photograph can start to look like thousands of other images. Sometimes it’s better to see the overall picture.

To achieve this image of Maria Sharapova, I positioned myself at the top level of the stadium where I had shot from as a teenager, and showed the view from the perspective of the spectator.

I was using a 45mm tilt-shift lens, which allowed me to produce something aesthetically different. It shows Sharapova in focus and her opponent, Justine Henin, out of focus. The image tells the story of her victory from the context of the thousands of people who had witnessed the moment. This perspective gives you an appreciation for the scale of the event that you don’t necessarily get with a long telephoto lens, where the background is completely blurred out.

This image was a gamble because there was no telling where and when the match was going to end. And predicting which direction she would look when she did win was a combination of experience and luck. I had to make a very big bet that she would turn around and look at the box where her family was sitting. Had she been on the other side of the court, there would be no image with that lens.

On a mental level you are conscious of what the chances are that she’ll be on the wrong side of the court, but also how she’s going to react and where she’s going to point to. And the fact is that you have only one chance to get it. There will be no repeats here. And if you don’t get it, no one cares if your battery died or your camera wasn’t formatted correctly, or you were soft or out of focus. It’s irrelevant.

The other risk I took was with respect to focusing. I was focusing manually, and if you look closely, the top of the racket and the sneakers are out of focus. So you can appreciate how razor-sharp you have to be on the focus during a live and evolving moment.

Despite those challenges, the photograph conveys the story of how Sharapova at this particular moment is at the center of the world, especially at the center of the tennis world, and that Henin is completely irrelevant and out of focus. The front page goes to the winner. The one who loses either never makes the paper or gets buried in history.

Story of a Moment

This image of a gymnast on the vault is another way to tell the story of sports—in this case, during the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, China.

The practical reality is that there were dozens of cameras in this venue, and the backgrounds I had to choose from were terribly distracting. But after some searching, I finally found one spot, one into which I could barely fit myself to get a decent angle to shoot the event with a 300mm lens wide open at f/2.8.

I chose this angle because the background contained the Olympic colors. It’s completely out of focus, but there are no distracting lines. Most important, there are no television cameras in the background, which was the real distraction.

Unlike Sharapova at the U.S. Open, this athlete was not the darling of the Olympics. Few in the crowds knew his name, especially because they were mostly Chinese and there to support their own team. So the choice to photograph the moment tight, without the faces of the crowds, was an editorial as well as an aesthetic decision.

This photograph becomes the story of an individual’s pursuit. It’s him against the world. It is all about that athlete and his performance. You have enough information to let you know that this is the Olympics, but the moment is all about him. Some events are about individual pursuits, whereas others are more symbolic of what they mean to the country. Those are the kinds of decisions you have to make.

Alexander Artemev of the USA team competes during the Men’s individual all-around final at the National Indoor Stadium during the 2008 Olympics.

ISO 1250 f/2.8 1/1250 300mm

Department of Transportation bridge painters threw up a wrench to Cesar Pazmino as they rose the flag from half-staff to full-staff on the Brooklyn tower of the Brooklyn Bridge following the 9/11 memorial (April 2002).

ISO 200 f/18 1/250 14mm

Symbolism As Story

Nine months after the 9/11 attacks I was on top of the Brooklyn Bridge, witnessing the flag being raised from half-mast back to full-mast as a sign saying, “Hey, we’re back,” or at least we’re no longer in mourning. We were still mourning, but at least we were moving back toward a normal life.

The reason I chose the wide-angle lens was a practical one. It’s a very small physical area on top of the Brooklyn Bridge on the stanchion. You can’t back up or you’ll fall right off. So you can’t use a telephoto lens.

If you made that same shot tighter, you would lose the top of the flag and the skyline of the city. It’s not an image about a guy catching a wrench. It’s really irrelevant, but it’s the element that helps make the moment decisive. It’s not about the guys beneath him. There is no context to that. It’s not just about a flag. But if you conjoin all these elements—the flag, the men helping him, and the skyline with that one little wrench being thrown up—you have a story that speaks to what happened that day. It becomes a symbol of a city restoring itself.

And though the wrench is not the story, it’s the telling gesture, the decisive moment that helps complete the image, because without it there would be something missing.

I remember feeling frustrated making this picture, because the scene itself wasn’t particularly dynamic. I chose a shutter speed, which was 1/250 second. 1/125 tends to blur, and 1/500 tends to freeze movement, but at 1/250, the edge of the flag has a little bit of movement to it.

And then you are just waiting, and you have a sense that this is downtown Manhattan at the lower left of the image and the now-empty skyline where the towers once stood. The flag is dead center, and that wrench solidifies this historical moment of New York’s history.

What separates a good image from a masterpiece is often found in the details. One inch to the left or to the right can differentiate a great image from a terrible image. The gesture here solidifies it. It’s also important that the flag stands above all, and that it appears to be larger than the human being. There is some intrinsic symbolism of the flag representing America, and here it is flying over the city and in many ways carrying it up.

Inclusion and Exclusion

When you are in the midst of a news story and you are seeing all hell break loose, or you are in a protest surrounded by hundreds of people, you have to exclude everything that is irrelevant to what you think the story is, because if you are busy photographing ancillary stuff or irrelevant stuff, you miss what’s important. You almost have to have blinders on to stay focused.

You have to stay focused on what that target is at all times, and it is constantly evolving during a breaking news story. And you have to constantly ask yourself, Am I photographing what’s important? Am I at the right place? Am I focusing on the right thing? Am I interpreting this correctly? The challenge becomes finding your target. Just because you know what you need to show, it doesn’t mean you can get there or that it will happen. It may have happened 5 minutes ago and you missed it.

You might think the story is clear in this image of the effigy being burned in Pakistan, but if you look carefully, you’ll see the man in the center is smiling. This event happened after Friday prayers, where someone decided to put a Yankees T-shirt on an effigy and the crowds decided to play for the cameras.

If you take a careful look at that image, the symbolism of what they are doing is unmistakable, but if you look at a lot of these guys’ faces, they are having fun. These are not passionate, rabid, crazy people. Choosing to include those smiling faces helps to tell a part of the story. Excluding it transforms the image into something completely different.

Two weeks after 9/11 I am at a rally surrounded by a mullah’s security detail. They are definitely not my friends. The mullah is speaking into a microphone and repeatedly shouting, “Kill America. Kill Bush.” And tens of thousands of people are repeating the words after him. And here I am making images literally at his feet, visible to all those people.

I am staring directly at his security detail. This image on page 33 reflects a 30- or 40-second exchange. He didn’t flinch. I didn’t flinch. This wasn’t an ego battle. I wasn’t there to confront the man. I wasn’t looking to make a point. I was there to try to capture this kind of look. I was a journalist and relatively safe, but under any other context if someone were to look at me like that, there wouldn’t be any doubt that this man was possessed by tremendous hatred for who I was and what I represented.

Self-proclaimed supporters of Osama bin Laden burned an effigy of President Bush as thousands gathered in the streets of Peshawar following morning prayers at the Qasim Ali Khan Mosque (September 2001).

You have to stay focused on what that target is at all times, and it is constantly evolving during a breaking news story. And you have to constantly ask yourself, Am I photographing what’s important? Am I at the right place? Am I focusing on the right thing?

What I read in his eyes was, “You are not welcome here, and if this were any other circumstances I would cut your throat. You are not our friends. We are at war.” And that is the storytelling element of this image, because in the photograph this man is looking at the viewer.

If this were created vertically as a portrait, the same image would have lost its context. This is not a portrait. This is not meant to go on the National Geographic cover. I shot this with a 24mm lens, and I purposely included the two guys right behind him. The story of this image, which was important to express, was that he wasn’t alone. He had people around him, men who were of the same spirit.

Although there’s an intrinsic beauty to this man’s face, there is no doubt that he is a warrior. He is a disciplined, serious guy. At a basic level, this man has one goal in life: he’s on the security detail to protect the mullah and anyone who’s a threat to him. However, on another level you could reasonably assume, given what the mullah was preaching, that he was part of an effort to kill the enemies of Islam. I represented that, and the readers of this newspaper, looking at this image, could definitely feel that.

Guard to one of the local clerics join a crowd of more than 15,000 pro-Taliban supporters as they listen to speeches given by religious leaders during an anti-American rally (September 2001).