6. Political Economy

“Don’t fight the Fed.”

—Trading adage

“Nations, like individuals, cannot become desperate gamblers with impunity. Punishment is sure to overtake them sooner or later.”

—Charles MacKay, Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

On the evening of Thursday, November 22, 2012, Egyptian President Mohammed Morsi granted himself sweeping new powers.1 The announcement was made at the start of the traditional Egyptian weekend but that did not prevent immediate protests to the President’s actions. It was immediately clear that although large segments of the Egyptian populace would reject the presidential decree, many would also support it. On Sunday, November 25, 2012—the first day the Egyptian markets were open after the announcement—fears of a slide away from democracy and of continued civil unrest as a result of the move sent the Egyptian stock market down nearly 10%.2

Political actions are an important source of market shocks. They are not limited to developing countries but occur in all countries. The comments of politicians; the actions of policymakers, government officials, and central bankers; and the outcomes of elections, court decisions, expropriations, wars, and terrorist acts all impact the market. This chapter breaks down important political crises—both historical and recent—and explains their importance to your trading strategy.

Political Shocks—Terrorist Actions, Wars, Assassinations, and Policy Actions

The U.S. has had its share of politically induced market shocks. For example, the Dow Jones Industrial Average closed down 7% on September 17, 2001 after the stock market reopened following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.3 The sharp decline in stock prices occurred despite a 50-basis-point cut in the targeted Fed funds rate by the Federal Reserve before the market opened.4

On Monday, December 8, 1941—the first day of trading after the Sunday, December 7, 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese Navy—the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell about 3.4%.5 When President Kennedy was assassinated on Friday, November 22, 1963, the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell about 3% in panic trading between the time that the news reached the floor at 1:41 p.m. and when the NYSE closed trading early at 2:07 p.m.6 Yet it more than recovered when the market reopened the following Tuesday and rose 4.5%. This example contrasts in both magnitude and duration to the selloff in the Dow during April and May 1962 when President Kennedy threatened to nationalize the steel industry. Brown [1991] describes some of the price action:

“Steel issues were crushed, Big Steel falling from a 1961 top at 91 to 38...[a number of stocks] lost over 60 percent from the late 1961 tops. IBM[’s]...607 to 300 drop was eyecatching.”7

The so-called “Kennedy Panic” or “Steel Crisis” climaxed on May 28 when the Dow Jones Industrial Average fell 5.7% followed by a “relief rally” the next day of 4.7%.8

The Steel Crisis also contrasts with another precarious event in the Kennedy administration: the Cuban Missile Crisis. Faced with the threat of nuclear annihilation, you would expect the market to tank. Instead, on October 23, 1962 (the first trading day after President Kennedy addressed the nation about the presence of Soviet missiles in Cuba), the Dow closed 1.9% higher.

At first glance, it might appear that the rally was an extreme mispricing, but as Forbes points out, what’s the point in profiting on the end of the world?

“The muted decline relative to the steel meltdown also is a stunning example of the market’s cold logic: There’s no point to making a winning bet on an atomic holocaust.”9

The end of the Cuban Missile Crisis precipitated a strong rally that continued through November.10 These examples show that sometimes gigantic geopolitical events, like the Cuban Missile Crisis, can have a relatively muted effect on the market when compared to seemingly less important events, such as the so-called “Kennedy Panic.”

The 2000 U.S. Presidential Election

Even the anticipation of changes in government can have important effects on the market. Take U.S. presidential elections, for example. A paper found that the market expected:

“...higher equity prices, interest rates and oil prices, and a stronger dollar under a George W. Bush presidency than under John Kerry [in 2004]. A similar Republican-Democrat differential was...observed [in 2000].”11

After-hours trading on November 6th and 7th, 2000 show large swings in the December 2000 delivery NASDAQ 100 stock index futures price. Presidential elections in the U.S. are determined by the electoral college. After Florida was called for Gore at 8 p.m. EST, an existing negative downtrend accelerated, leading to a sharp drop in prices. By 10 p.m. EST, the market had recovered and the call of a Gore victory was rescinded. The market trended slightly higher until Bush was called the victor in Florida at 2:15 a.m. EST on November 7, at which point the futures spiked. This spike was relatively short lived, because by 4 a.m. the call of a Bush victory was itself rescinded, and the market dropped accordingly. By 6 a.m., the market was very slightly up from its level at 6 p.m. the previous day.

S&P 500 stock index futures with a December 2000 delivery date also followed this pattern, although to a lesser degree than the NASDAQ futures. Trade-weighted currency futures with a December 2000 delivery also followed this trend, to a minor degree.

This example shows clear correlations between elections and market results. However, its applicability to a trading strategy, aside from being aware that elections move markets, is tenuous. Considering the election was extremely close and eventually decided in court, trading off this event would have been difficult. Clearly, the market was much more receptive to a Bush victory than a Gore one.

The implications for the economy as a whole are less clear. As the study noted, this does not necessarily mean that Republican presidents are “better” for the economy.12

The Boston Globe, on November 2, 2012, reported that median economic growth under Democratic presidents since 1949 was higher than that of Republicans. Democratic presidents have presided over periods of 4.2% median GDP growth, whereas Republican administrations have presided over periods of 2.6% median GDP growth.13 The same article noted:

“Markets have been at their best when there’s a Democratic president and a Republican Congress. ... [producing] 15 percent average annual returns [versus] ... 5 percent returns with a Republican president and Democrat-controlled Congress.”14

Perhaps divided government is best for economic growth. Determining how presidents affect the economy is difficult because over the entire history of the United States, there have been fewer than 50 presidents, and of course, even fewer in the modern era. This sample size is relatively small. Further confounding the analysis is the fact that the president has relatively little power over the economy—the House of Representatives has much of the power given that the U.S. Constitution states: “All bills for raising Revenue shall originate in the House of Representatives.”15 It is clear that in many Presidential elections, the market has a preferred candidate—and the market will quickly react to election news. The effect of any single party or candidate on the stock market as a whole is a much more complicated question.

Expropriation

Not all political shocks are matters of life or death—but they can still be important. In many crises, moves of the market force the government to act. But sometimes, government actions move the market. Take Argentina’s de facto nationalization of the energy company YPF (Yacimientos Petrolíferos Fiscales). In a move that was later criticized by members of the European Parliament as “an attack on the exercise of free enterprise” on April 16, 2012, Argentina announced plans to effectively nationalize YPF, which was also a major oil producer.16

This shock reverberated around the world as YPF was largely owned by Spanish energy company Repsol. Professor Aswath Damodaran at NYU Stern wrote:

“...Repsol...majority owner of YPF...stands to lose several billion dollars...the stock price of YPF, already down about 50% this year, plunged another 21% in New York trading.”17

But Argentina itself faced a backlash, as the cost of insuring the government of Argentina against default rose.18

The YPF shock reverberated for months. When YPF went on a road tour for new investment, it came up empty. The Associated Press noted that YPF had finished the tour without obtaining any new investors despite the fact that:

“YPF President Miguel Galuccio had 40 meetings with 70 businesses and investors in [several cities], inviting them to help develop the world’s third-largest reserves of shale oil and natural gas.”19

YPF later claimed it was a “non-deal road show,” which sounds precisely like what you would say if your road show failed to generate any investment. Even giving YPF the benefit of the doubt, clearly government nationalization can and will have a chilling effect on stock prices long after the initial expropriation has taken place.

YPF did announce a deal with Chevron, which the Financial Times noted was a reflection of the fact that oil companies:

“could be persuaded to be pragmatic and overcome their qualms about doing business with a government which has proved itself often enough to be unpredictable—provided the price is right.”20

It is probably safe to assume the terms of the deal with Chevron were heavily influenced by the recent seizure of YPF—in effect giving Argentina a worse deal.

You don’t have to be a genius to realize that the result of government expropriation is both long term and far reaching. Indeed, evidence exists that the fear of expropriation results in companies trading at a lower P/E ratio. Analysis on Professor Aswath Damodaran’s blog shows that Russian and Venezuelan companies, on average, trade at a discount when compared to their emerging market peers. In January 2012, Venezuelan companies traded at a P/E of below 5, while Russian companies traded at a P/E of below 8.21 This compares relatively poorly to countries such as South Africa, Singapore, India, and Turkey—whose P/E ratios are above 10—and even more poorly against Peru, Chile, and Brazil who boast P/E ratios above 12.

No one can predict the future, and hindsight is 20/20. But some things were clear: Argentina was willing to nationalize the holdings of large, powerful foreign companies; it was willing to falsify official economic statistics;22 it had a recent history of major economic crises; and expropriation reduced (and would probably continue to reduce foreigners’ trust) in Argentina.

All of these things act as barriers to investment. They also would likely result in reduced investment and help continue the slide of the currency that had been in decline since mid-2008. Even before the YPF crisis, Argentina had introduced money-sniffing dogs at border crossings to reduce currency flight,23 and had falsified some economic statistics so blatantly that the Economist stopped publishing Argentina’s official inflation numbers.24

Considering that few people would have been able to accurately predict the exact timing of the move by Argentine President Cristina Kirchner’s government, how could you trade off it after the news broke? What were the implications of this move for investments in Argentina, South America, and the rest of the world?

Because of the sheer power of government, its action in one sector will have a predictable effect across the economy. After a government starts going after powerful oil companies, what’s to stop it from going after the banks? If a government is willing to falsify official inflation statistics, why should investors believe it is serious about running a transparent, modern economy?

Declining investment and trust in any market lead to predictable outcomes: Falls in banking stocks or in the currency, or downgrades by international ratings agencies. These things are exactly what happened in Argentina’s case.

The verdict of the markets was swift and broad—with ramifications continuing beyond the fall in the share price of Repsol, YPF’s former majority owner. The Wall Street Journal, in April 2012, reported:

“...Standard & Poor’s Ratings Services lowered its outlook on Argentina to negative from stable, citing the country’s decision to nationalize YPF as well as restrictions on international trade.”25

Nationalization and expropriation of companies sends a terrible signal to international investors. Taken to an extreme, the resulting lack of faith in the willingness of a country to honor its commitments will eventually result in its inability to honor its commitments.

After the shock hit, the smart money would have shorted Argentinian currency, sold Argentine banking stocks, and went negative on any company with large exposure to the Argentinean market. Few sure rules exist in trading, but here’s one of them: If the government starts taking people’s money, get out while you can.

This shock precipitated a serious mood change in global markets, and its effects were felt for months to come. Investors could have profited from such a move even if they missed the initial fall in prices by predicting the longer-term slide in the Argentine peso and by anticipating the souring business climate in the country. Indeed, as of late 2012, the Argentine government was locked in a battle to take over Charin, the largest media group in Argentina, and a former ally of the government in what the Economist claims was “another step in the building of a pro-government broadcasting monopoly.”26

As shown by other countries such as Venezuela, after a government decides to start down the dangerous path of reckless nationalization, more—not less—action is to be expected in the future.

Could Argentina’s expropriation have been predicted, before the shock? Lloyds suggests that:

“Political ideology continues to drive the risk of nationalization for foreign companies operating in some Latin American and African countries.”27

Predicting the exact timing or the details of large expropriations such as Argentina’s would have been difficult, but determining windows of increased likelihood (based on elections, business cycles, statements to the media, and so on) arguably would have been possible. Profiting from these shocks in the long term is also possible because shocks like this one have long-term effects with spillovers to other markets, such as the sovereign credit default market.

Cooling the Economy and Markets

In what the Wall Street Journal noted was “its biggest drop in a decade,” the Shanghai Composite index fell by 8.8% on February 27, 2007.28 This represented a loss of about $140 billion.29 Although there was no proximate cause, some suggested that many investors were worried about rumored government attempts to cool down the economy. Such cooling might have appeared necessary because—despite the huge losses of February 27—the crash took the market back to the level it was at a mere six trading days earlier (as the market had risen 11% over those six trading days). After it was all said and done, even a loss of 8.8% left markets slightly above their level on February 9. This reaction is not a testament to it being a small break—it was the largest in a decade—but to the increasingly overheated nature of the Chinese stock market, which had risen 130% in 2006.30

However, the sudden plunge in stock prices wasn’t just confined to China. It spread around the world. The news had a large and, heretofore rare impact on U.S. markets, leading to the largest fall in the Dow since the immediate aftermath of the September 11 attacks. With a fall of more than 400 points, it was—at that time—the seventh-largest, one-day point drop ever. In the midst of this calamity, treasuries rose as investors sought refuge from the storm while gold—often seen as another safe asset—in fact fell in what CNN Money attributed to a bet on slower growth in China.31

Time noted the sweeping effects of the plunge reverberating around the globe:

“...as this new outbreak of investor gloom spread, India’s main stock index tumbled 4%, Singapore’s dropped 3.7%, Japan’s fell 2.9%, South Korea’s lost 2.6%, and Hong Kong’s slipped 2.5%.”32

The old maxim, “When America sneezes, the rest of the world gets a cold” may have to be discarded to reflect the growing influence of emerging markets on world markets in general, and the influence of China in particular. Although the effects of the Chinese plunge in stock prices on world markets were not devastating, it reinforced the newfound economic power that the People’s Republic brings to the table. Traders should expect this influence to continue into the future.

Central Banks to the Rescue

The collapse of Lehman Brothers on September 15, 2008 set off a firestorm in financial markets around the world. Rather than die out, problems appeared to grow in financial markets and the real economy. The global selloff in share markets was recounted in the following article in the New York Times for Wednesday, October 8, 2008:

“...Japanese stocks plunged 9.4 percent...London declined 6.7 percent...Paris fell 8.2 percent, Frankfurt fell 7.5 percent...Hong Kong...slumped 8.2 percent...”33

On the same day, the U.K. government announced plans for the partial nationalization of major British banks and plans by the Bank of England to provide more than 200 billion pounds to British banks. Unbeknownst to the British prime minister and his government, the head of the Bank of England was conversing with his counterparts at other key central banks over the need for a coordinated cut in interest rates.34

Against that market backdrop and shortly later that same day, in what the New York Times called a “move of unprecedented scope,” the Federal Reserve, the Bank of England, the European Central Bank, the Swedish Riksbank, and Canada’s central bank cut benchmark interest rates by half of a percentage point.35 The Peoples’ Bank of China, technically acting alone, joined, in all but name, by reducing interest rates by 27 basis points and lowering bank reserve requirements. The Swiss National Bank also cut rates by 50 basis points. The Bank of Japan did nothing—given the low level of Japanese interest rates at the time—but supported the global action.36

The coordinated action answered the call of many market participants for such a move to encourage bank lending to companies and retard potential corporate failures.37 An ancillary objective was to restore confidence in financial markets. The results of the action were swift but short lived—a European stock market rally followed by continued losses for stock markets that had been in a downtrend for days.

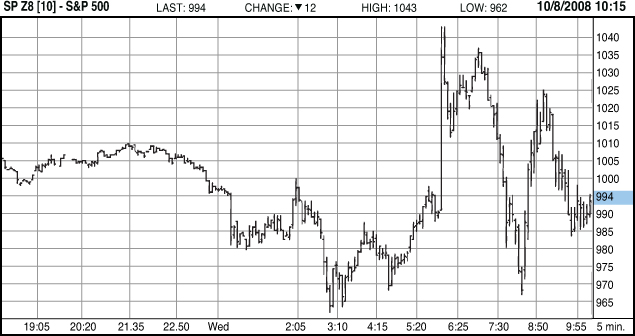

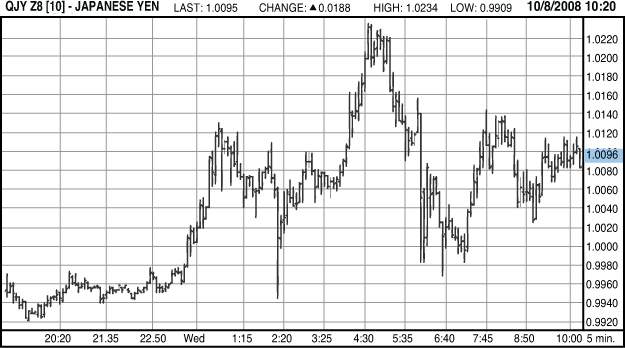

Figure 6-1 shows the reaction to news of the announcement in the S&P 500 stock index futures market. Figure 6-2 summarizes the reaction of the Japanese yen futures market to the news. Interestingly, the timing of the initial reaction to the price moves to the news does not line up precisely in the two five-minute price charts. However, both markets soon returned to levels that existed before the announcement was made.

(Reprinted with permission of the CME Group.)

Figure 6-1. This chart depicts the reaction of the December 2008 delivery E-Mini S&P 500 Stock Index futures contract to news of the coordinated cut in interest rates by central banks on October 8, 2008.

(Reprinted with permission of the CME Group.)

Figure 6-2. This chart depicts the reaction of the December 2008 delivery Japanese Yen futures contract to news of the coordinated cut in interest rates by central banks on October 8, 2008.

So what is the principal trading lesson? In the midst of a crisis, government or central bank actions can only do so much. The fundamentals of the economy were weak—and interest rate cuts couldn’t change that. Moreover, it was not clear that cuts in central bank rates would translate into lower interest rates for businesses or that those businesses needing funds would be able to borrow at the new rates. Olaf Unteroberdoerster at the IMF summed up the market zeitgeist neatly, saying:

“The key lesson is when you face a confidence issue where the market participants no longer trust each other, the conventional macroeconomic tools are not as effective.”38

The episode also illustrates how “good news” in a bear market might have only a transitory impact. One implication from that behavior is that anyone betting on the market’s reaction to similar announcements in bear markets should plan for a short trade horizon. Something similar can be said for the impact of “bad news” in a bull market environment; namely, the effects might be transitory.

Central Banks as Speculators

Jerome Kerviel (Société Générale S.A., €4.9 billion), Kweku Adoboli, (UBS, $2.3 billion), Yasuo Hamanaka (Sumitomo, $2.6 billion), Nick Leeson (Barings, £830 million), and Toshihide Iguchi (Daiwa Bank, $1.1 billion) all share the dubious distinction of being convicted rogue traders each responsible for losses in excess of $1 billion for their firms. To add insult to injury, several of their firms paid substantial fines to the relevant regulatory authorities as well for lax regulation, attempting to conceal the loss from authorities, or market abuse.39 These rogue trading losses inflicted considerable damage on the stock prices of their firms. Indeed, Nick Leeson’s rogue trading losses took Barings down.

However, the losses incurred by rogue traders pale in comparison with the losses incurred by many central banks in their attempts to push exchange rates in a desired direction or maintain a given exchange rate. Many of these losses only become apparent in the wake of market shocks that they induce.

The Swiss National Bank

Between March 2009 and June 2010, Switzerland’s central bank, the Swiss National Bank, intervened repeatedly in the foreign exchange markets by buying dollars and pounds sterling (and selling Swiss francs) to slow the appreciation of the Swiss franc. These efforts were ultimately unsuccessful as demand for Swiss francs increased and with it the relative value of the Swiss franc:

“...The Swiss central bank said its currency interventions to help stem the franc’s relentless rise against the euro, U.S. dollar and the U.K. pound resulted in exchange-rate losses of 32.7 billion francs in 2010...”40

The Swiss National Bank is unusual in that, unlike most central banks, it is also a publicly traded corporation. The behavior of its stock price is depicted in Figure 6-3. The Swiss National Bank shocked the foreign exchange markets when it suddenly pegged the Swiss franc to the Euro on September 6, 2011 (see Chapter 10, “Flight to Safety”).

(Reprinted with permission from Yahoo! Inc. 2013 Yahoo! Inc. [YAHOO! and the YAHOO! logo are trademarks of Yahoo! Inc.])

Figure 6-3. This chart depicts the behavior of the Swiss National Bank’s stock price.

The Bank of Japan

The losses experienced by the Swiss National Bank were small in comparison with the estimated losses that the Bank of Japan suffered from its repeated interventions in the currency market (usually to weaken the yen against the U.S. dollar) over the years. The Bank of Japan has enjoyed limited (and often fleeting) success in these efforts. This success came at a high cost to the Japanese government and its citizens. JP Morgan estimated the Japanese government lost more than $512 billion from past sales of the yen.41

Those in favor of yen-weakening policies might argue that the $512 billion was the price to pay for saving Japanese industry in the face of excessive currency appreciation. The argument is that short of action, the currency would have appreciated much more. Those on the other side argue that Japan has wasted over half of a trillion dollars in a Sisyphean task of trying to move the currency markets.

Still others who believe in a strong currency argue that, in fact, a stronger yen benefits the country despite the possible deleterious effects on manufacturing due to higher prices paid by foreign consumers. They argue that economies based on a strong currency can adapt and that having a strong currency is a sign of overall economic strength, not weakness.

Whether a strong currency is detrimental to an economy (especially a manufacturing-based one) is an open question. What is clear is that shocks to the FX market that usually accompany interventions are important to understand.

As with the change in any market price, there are winners and losers. A stronger yen makes Japanese exports more expensive. It also makes imported goods cheaper in Japan. Some industries are sensitive to changes in exchange rates. For instance, CNN Money reported in October 2011 that “For every 1 yen appreciation against the dollar, Toyota, the car manufacturer, loses 30 billion yen ($380 million) in profits.”42

On October 31, 2011, Japan intervened in currency markets to weaken the yen. In what was the third intervention of 2011, then finance minister Jun Azumi laid out a case for weakening of the yen:

“The yen’s appreciation might close down factories and I cannot tolerate it.”43

Contemporary news reports indicated that the Bank of Japan spent 7.7 trillion yen (or about $98.5 billion) in its attempt to move the market.44 It succeeded. Bloomberg reported that the yen dropped “as much as 4.9 percent” due to the intervention and that it fell against more than 150 currencies tracked by Bloomberg.45 However, even massive intervention by the Bank of Japan could only temporarily influence but not reverse the market’s direction. Vassili Serebriakov at Wells Fargo & Co. noted:

“The move has already been partly reversed, and it still suggests that the market’s bias is strongly toward buying the yen rather than selling the yen.”46

Action by the Japanese government may have succeeded in the sense that the yen did not appreciate to levels it saw immediately before the intervention. However, “success” in this case is defined as decreasing the value of Japanese currency relative to other currencies. Holders of yen-denominated assets suffered a decline in the foreign exchange value of their holdings. The Bank of Japan believes that the Japanese economy can be strengthened by weakening the foreign exchange value of the Japanese yen.

Can Bank of Japan interventions be easily anticipated? This was the third time in 2011 Japan had intervened in the currency market to weaken the yen. Finance minister Azumi had warned that the government would act against speculators. Although predicting the exact timing of the move would be extremely difficult, if not next to impossible, it was widely known that the Japanese government was concerned about the rise in the yen.

This concern could have meant there was an implicit floor in the appreciation of the yen; however, that would be a risky game to play. Worries about a potential euro collapse were very real at that time. Any collapse in the euro likely would have led to a surge in the value of the yen. A short yen position would require tight stops in such an environment.

Governments sometimes are unambiguous about the direction and amount they desire markets to move. In the fall of 2012, for example, Shinzo Abe campaigned on a platform of requiring the Bank of Japan to pursue a 2% inflation target and to print yen until that was achieved. At the time, the yen was trading in the low 80s to the dollar. His party—the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP)—was favored to win in the December 16th 2012 parliamentary (Diet) election. The LDP took power and Abe was elected prime minister. Shortly after his election, Prime Minister Abe indicated that he would like to see an exchange rate of 90 yen to one U.S. dollar at a time when the yen was trading at around 85 yen to the U.S. dollar.47 On January 23, 2013, the Japanese Government and the Bank of Japan issued a joint statement adopting the 2% inflation target policy.48 The weak yen policy may or may not stimulate the Japanese economy. However, the promise to pursue such a policy during the election and the adoption of the policy after the election provided traders with profitable trading opportunities in the yen with market participants told the direction and amount of weakening that was desired. Moreover, this is not a case of 20/20 hindsight of what one might have done after the markets had already moved. A number of prominent hedge fund managers interpreted the prospective election of Abe as a catalyst for a sharply weaker yen and higher Japanese stock prices—and their predictions were reported in the financial press at the time.49 Shinzo Abe was elected prime minister. The yen weakened as expected. Japanese stocks rallied as expected. And the analysis that would have led a trader to short the yen before the December 16, 2012 parliamentary election was political as much as economic.

Bank of England

The ill-fated attempt by the Bank of England to maintain a fixed peg against the Deutschemark in September 1992 made George Soros a household name when his bets against the pound sterling earned his hedge fund an estimated $1 billion. One reason Soros was able to earn so much from his bets against the pound sterling was that he had a willing counterparty—the Bank of England—effectively willing to take the other side of his trades. Moreover, as Webb [2007] points out, he was able to do so by taking on limited risk.50 Simply put, if the peg held, he would lose a little; but if the peg broke, he stood to gain a lot. This was a one-sided bet.51

Although George Soros became famous as “the man who broke the Bank of England,” many other traders with similar positions benefitted when the peg was broken even if they didn’t receive the same public attention that Soros did. This fact becomes apparent when you consider the foreign exchange losses that the Bank of England suffered in trying to prevent the devaluation. Contemporary press accounts estimated that the Bank of England spent £15 billion trying to defend the peg.52 Official papers later revealed the extent of the losses incurred by the Bank of England in trying to maintain the currency peg as:

“...£3.3bn ($6.1bn). In the final days of intervention some £800m was lost...”53

Put differently, if the $1 billion gain attributed to Soros’ hedge fund was correct, currency traders betting against the pound sterling gained another $5 billion from the Bank of England. This number understates the total losses because it ignores losses that other central banks suffered trying to maintain the sterling peg.

The losses from the failed attempt to maintain the peg were, of course, ultimately borne by U.K. taxpayers. This amounted to a loss of about £57 for every man, woman, and child in the U.K. at the time.

Bank Negara Malaysia

Perhaps one of the most unusual cases of central bank speculation in the foreign exchange market was also one of the most direct ones. That was the strange case of Bank Negara Malaysia in the early 1990s. According to press reports, Bank Negara Malaysia lost 10 billion ringgits in 1992 largely from trying to defend the pound sterling and another 5.7 billion ringgits in 1993 from failed speculation in the currency markets.54 Why the central bank of Malaysia chose to defend the pound sterling in 1992 is puzzling from a trading perspective. Like the Bank of England, the rewards from success would have been minimal. The losses if the peg broke would be substantial. As Southerners in the USA might put it, Malaysia “had no dog in this fight” but chose to fight anyway.

Trading Lessons from Central Bank Interventions in the FX Market

Many shocks induced by central bank interventions in the currency markets are anything but permanent. Unless a long-term guarantee is made (such as the Swiss pledge to “buy foreign currency in unlimited quantities”), currency shocks are likely to be short lived.55 For instance, when Japan intervened in the currency market to weaken the yen on August 4, 2011, it was only a week until the yen had again appreciated to the levels before that intervention.56 After the October 31, 2011 intervention, the yen did not quite reach its pre-intervention valuation, but it did lose some of the weakness so dearly bought by the finance minister. As shown in Figure 6-4, the yen eventually strengthened further after several months trending between 76 and 78 yen per dollar. This might have been due to global macro factors, such as the European sovereign debt crisis that made the Japanese yen a safe haven currency to some market participants.

(Reprinted with permission of XE.com and the XE Currency Services Team.)

Figure 6-4. This chart depicts the behavior of the Japanese yen U.S. dollar exchange rate from August 2011 to June 2012.

Central banks frequently create one-sided trading opportunities for speculators when trying to defend a fixed exchange rate for their currency or push the exchange rate in the direction they desire. Moreover, by standing ready to trade large amounts of currency to achieve their policy objectives, they facilitate the desire of speculators who want to do size (place large bets). This incentivizes the types of trades that central banks want to discourage and that might give rise to currency crises.

Although such actions assist currency speculators it is not clear that such actions actually help achieve the desired policy objective. The examples of speculation by central banks—whether to achieve a policy objective or otherwise—illustrate the difficulty that even large players in financial markets, such as central banks, have in trying to influence market prices. The examples also highlight the substantial losses that central banks incur (and ultimately taxpayers bear) from such trades on financial markets. Central bank losses don’t always receive the public scrutiny they deserve. The fact that the losses are borne by the central bank does not alter their fundamental nature. Namely, the losses are really wealth transfers from taxpayers to speculators.

Trading Lessons

As long as we have governments, governmental actions (or inaction) will affect the market.

While governments in industrialized countries rarely intervene in the market directly, their actions can impact market prices. Direct intervention, when it takes place, can significantly move markets. In general, governments often set the long-term mood of markets through regulations and the business climate they create. In some instances, governments make moves that have swift and broad impacts on the market. Understanding a government’s general political orientation can pay dividends.

Political shocks have wide-reaching effects. The threat of war or destruction can send the market sharply down. However, as seen in the Cuban Missile Crisis example, apocalyptic threats are often ignored. There is no point in making money off the end of the world.

Governments determined to expropriate assets and violate property rights will have their way—as they have already forsaken the impartial rule of law. That’s why expropriation leads to long-term trends of economic malaise and leads to lower PE ratios for companies in those countries. Traders can short the country’s currency or find other ways to profit from the resulting decline. Most importantly, traders should realize that they could be next, and only after ensuring that your assets are protected should you attempt to make money in ventures related to deteriorating economies.

Expropriation is in contrast to governments that intervene in the market, but simply as a powerful—but not omnipotent—force. Examples include the Hong Kong Monetary Authority (HKMA) and the Bank of England interventions. The Bank of England failed to protect itself and lost money, whereas HKMA waged war in the open markets when the Hong Kong dollar peg was attacked by speculators (examined in detail in Chapter 7). These epic struggles have clearly defined winners and losers. Often, they are also crises precipitated by non-governmental actors. More ambiguous situations—such as the Bank of Japan’s past interventions to weaken the yen—represent trading opportunities created by government that offer potential rewards to traders.

Traders need to remember that the biggest players in the market can move prices (at least for a while) and that some of the biggest players in the market are central banks.

In democracies, governments can sometimes unintentionally reveal future action(s). This has important implications for trading. In the case of Japan, the closure of factories was bad for the country economically—but also politically unpopular. Thus there was pressure to prop up manufacturing with a weaker yen. In the case of Argentina, years of anti-business political decisions had not destroyed the government’s mandate, and it felt it could continue its actions. Indeed, the seizure of YPF was couched in nationalist terms, and the target—a foreign, Spanish company—all too easy.

Elections have consequences. The pursuit of new fiscal or monetary policies can have dramatic effects on markets, as shown by the 2012 election of Shinzo Abe as Japanese prime minister. At the same time, the likely financial market consequences of elections provide traders with potential trading opportunities that may not be fully priced into the market.

This chapter illustrates that sometimes your trading edge might be in understanding the nexus of politics and financial markets.

Endnotes

1. Reuters, “Egypt’s Morsi to meet judges over power grab.” Globe and Mail. November 25, 2012. http://www.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/egyptian-stock-market-tumbles-after-president-morsis-power-grab/article5639047/?cmpid=rss1.

2. Fleishman, J. and R. Abdellatif, “Egypt stock exchange falls, protesters converge on Tharir Square.” November 25, 2012. L.A. Times. http://articles.latimes.com/2012/nov/25/world/la-fg-egypt-protests-20121126.

3. “New York Stock Exchange Reopens to Sharp Losses.” PBS Online News Hour. http://www.pbs.org/newshour/updates/september01/stock_exchange_9-17b.html.

4. Ibid.

5. Brown, J.D., 101 Years on Wall Street: An Investor’s Almanac, Prentice-Hall. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1991.

6. Ibid.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.

9. Simons, D., “Missile Crisis, Market Sanity.” Forbes. October, 16, 2002. http://www.forbes.com/2002/10/16/1016cuba.html.

10. Brown, J.D., 101 Years on Wall Street: An Investor’s Almanac, Prentice-Hall. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, 1991.

11. Snowberg, E., J. Wolfers, and E. Zitzewitz, “Partisan Impacts on the Economy: Evidence from Prediction Markets and Close Elections.” http://bpp.wharton.upenn.edu/jwolfers/Papers/Snowberg-Wolfers-Zitzewitz%20-%20Close%20Elections.pdf.

12. Snowberg, E., J. Wolfers, and J. E. Zitzewitz, “Partisan Impacts on the Economy: Evidence from Prediction Markets and Close Elections.” http://bpp.wharton.upenn.edu/jwolfers/Papers/Snowberg-Wolfers-Zitzewitz%20-%20Close%20Elections.pdf.

13. Healy, B., “Economic data show more growth under Democrats.” Boston Globe. November, 02, 2012. http://www.bostonglobe.com/business/2012/11/01/stocks-story/imJJjC7EHDJwQJCtTB2b4O/story.html.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.

16. BBC News, “European Parliament Condemns YPF Nationalisation.” April 20, 2012. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-latin-america-17794340.

17. Damodaran, A., “Governments and Value: Part 1- Nationalization Risk. Musing on Markets.” April 17, 2012. http://www.aswathdamodaran.blogspot.com/2012/04/governments-and-value-part-1.html.

18. “Fill ’er up.” The Economist. April 21, 2012. http://www.economist.com/node/21553070.

19. “Argentina’s YPF oil company runs empty on U.S. tour.” Associated Press. September 28, 2012. http://bigstory.ap.org/article/argentinas-ypf-oil-company-runs-empty-us-tour.

20. Webber, J., “YPF Moves Towards Tie-up with Chevron.” Financial Times, August 24, 2012. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/e7807812-edf5-11e1-a9d7-00144feab49a.html#axzz2GHq3fRc0.

21. “PE Ratios across Emerging Markets.” January 2012. http://3.bp.blogspot.com/-blwlExFUDbk/T43CRXuLU_I/AAAAAAAAALk/c7sClAbJy-s/s1600/PE+ratios+in+emerging+markets.jpg.

22. “The price of cooking the books.” The Economist. February 25, 2012. http://www.economist.com/node/21548229.

23. “Argentina appeals to sniffer dogs to detect capital flight at border crossings.” MercoPress. December 19, 2011. http://en.mercopress.com/2011/12/19/argentina-appeals-to-sniffer-dogs-to-detect-capital-flight-at-border-crossings.

24. “Don’t lie to me, Argentina.” The Economist. February 25, 2012. http://www.economist.com/node/21548242.

25. Rubin, B.F. and B. Fox. “Moody’s Lowers Outlook on 30 Argentine Banks.” Wall Street Journal. September 27, 2012. http://online.wsj.com/article/BT-CO-20120927-709987.html.

26. “Messenger shot.” The Economist. December 1, 2012. http://www.economist.com/news/americas/21567387-government-prepares-grab-television-empire-messenger-shot.

27. “Commodity Prices Increase Nationalisation Risk.” Lloyds. February 17, 2011. http://www.lloyds.com/news-and-insight/news-and-features/geopolitical/geopolitical-2011/commodity-prices-increase-nationalisation-risk.

28. Areddy, J. T., “Shanghai’s 8.8% Tumble Slams Emerging Markets.” Wall Street Journal. February 27, 2007. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB117257537957220485.html.

29. Torchia, A., “China stocks plunge 8.8 percent.” Reuters. February 27, 2007. http://www.reuters.com/article/2007/02/27/us-markets-china-stocks-close-idUSSHA22591220070227.

30. Powell, B., “China’s Stock Meltdown.” Time. February 28, 2007. http://www.time.com/time/business/article/0,8599,1594488,00.html.

31. Twin, A., “Brutal Day on Wall Street.” CNN Money. February 27, 2007. http://money.cnn.com/2007/02/27/markets/markets_0405/index.htm?cnn=yes.

32. Powell, B., Op. Cit. “China’s Stock Meltdown.”

33. Jolly, D., B. Wassener, and K. Bradsher, “Tokyo Shares Lose 9.4 Percent as Other Asian Markets Slide.” New York Times, October 8, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/08/business/worldbusiness/08iht-09markets.16775268.html.

34. Parker, G. and P.T. Larsen, “Plan on Table Along with the Tandoori Chicken.” Financial Times, October 9, 2008. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/a9a064c2-9588-11dd-aedd-000077b07658.html#axzz2E5ufXDif.

35. Dougherty, C. and E.L. Andrews, “Central Banks Coordinate Global Cut in Interest Rates.” New York Times, October 8, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/09/business/09fed.html?pagewanted=all.

36. Lanman, S., “Fed, ECB, Central Banks Cut Rates in Coordinated Move.” Bloomberg News, October 8, 2008. http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=newsarchive&sid=aEz2j_LH7n88.

37. Jolly, D., B. Wassener, and K. Bradsher, Op. Cit. “Tokyo Shares Slide.”

38. Dougherty, C., and E.L. Andrews, “Central Banks Coordinate Global Cut in Interest Rates.” New York Times, October 8, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/09/business/09fed.html?pagewanted=all.

39. For instance, the U.K. Financial Services Authority fined UBS £29.7 million for lax controls that facilitated rogue trading by Kweku Adoboli. (See Masters, B. and D. Schaefer, “UBS fined £29.7m Over Rogue Trader.” Financial Times, November 26, 2012. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/d58c9816-37a1-11e2-a97e-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2E5ufXDif.) The U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission fined Sumitomo $125 million for market abuse and ordered that Sumitomo put in an additional $25 million “to be paid either as restitution of damages proximately caused by virtue of the conduct underlying the violations found in the Order, in the manner set forth in this Order, or as part of the civil monetary penalty...” (see http://www.cftc.gov/ogc/oporders98/ogcfsumitomo.htm). Daiwa Bank was charged with attempting to conceal the trading losses from the Federal Reserve and paid a $340 million fine. (See Furtado, L. and P. Hurtado, “Olympus Whistleblower Said to Face Questions from the SEC in U.S. Investigation.” Bloomberg News, November 18, 2011. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-11-18/olympus-whistleblower-said-to-face-questions-by-sec-in-u-s-investigation.html.)

40. Maclucas, N., “SNB Posts Loss on Franc’s Strength.” Wall Street Journal, March 3, 2011. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704005404576177633861694972.html.

41. Fujioka, T., “Bank of Japan Warns Yen May Gain Two Days After Intervention.” Bloomberg Businessweek, November 2, 2011. http://www.businessweek.com/news/2011-11-02/bank-of-japan-warns-yen-may-gain-two-days-after-intervention.html.

42. Wakatsuki, Y., “Japan intervenes to weaken yen.” CNN Money. October 31, 2011. http://money.cnn.com/2011/10/31/markets/japan_yen.cnnw/index.htm.

43. Ibid.

44. “Japan Likely Intervened in FX Market After Last Monday.” Reuters News. November 7, 2011. http://www.reuters.com/article/2011/11/07/us-japan-intervention-idUSTRE7A60L320111107.

45. Savaira, C., “Yen Slides Most in Three Years After Japan Intervenes; Euro, Krone Weaken.” Bloomberg News, October 31, 2011. http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2011-10-31/yen-tumbles-4-as-japan-intervenes-to-sell-currency-third-time-this-year.html.

46. Ibid.

47. Ito, T., and W. Mallard, “Global Currency Tensions Rise,” Wall Street Journal, December 23, 2012. http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424127887324660404578196892204462394.html.

48. “Joint Statement of the Government and the Bank of Japan on Overcoming Deflation and Achieving Sustainable Economic Growth,” January 22, 2013. http://www.boj.or.jp/en/mopo/mpmdeci/state_2013/index.htm.

49. Jones, S., and B. McLannahan, “Hedge Funds Say Shorting Japan Will Work,” Financial Times, November 29, 2012.

50. Webb, R.I., Trading Catalysts: How Events Move Markets and Create Profit Opportunities, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: FT Press, 2007.

51. Mr. Soros characterized the trade as an “uneven bet” in an interview with Maria Bartiromo on the tenth anniversary of the pound sterling crisis on September 16, 2002. (See CNBC, “After Hours with Maria Bartiromo,” interview with George Soros, September 16, 2002.)

52. Whitebloom, S., “Sterling Crisis—Forex Frenzy Nets #900m.” The Observer, September 20, 1992.

53. Studermann, F. and J. Blitz, “Revelations on UK Exit from ERM Go from Drama to Farce.” Financial Times, February 10, 2005. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/e59c18e4-7b0c-11d9-a8c9-00000e2511c8.html#axzz2E7C7jZ00.

54. Duthie, S., “New Governor at Bank Negara Has Tough Job.” Asian Wall Street Journal, April 11, 1994.

55. Garnham, P. and H. Simonian, “SNB Stuns Market with Franc Action.” Financial Times. September 6, 2011. http://www.ft.com/intl/cms/s/0/f5a361ce-d862-11e0-8f0a-00144feabdc0.html.

56. Tabuchi, H., “Japan Acts Alone to Weaken Its Currency.” New York Times. October 31, 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/11/01/business/global/japanese-officials-intervene-to-weaken-yen.html.