29. Lewis & Clark

,

The project team makes an early investment to explore the domain and investigate its potential.

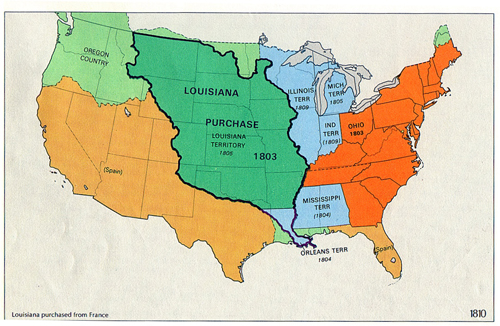

In 1803, the United States was made up of the few states that lay between the Great Lakes and the Atlantic seaboard. President Thomas Jefferson extended the country by buying territory from France—the Louisiana Purchase. The Purchase was known only by the description “the drainage of the Missouri River.” Nobody quite knew what that meant, including Jefferson. At the time, this was unknown country, inhabited only by the native nations and the occasional French trapper. To find out what he had bought on behalf of the United States, Jefferson commissioned Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to lead an expedition to explore the newly acquired territory and to assess its potential for trade and settlement. A party of 33 people—the Corps of Discovery—set out from Illinois in May 1804. When the explorers returned in September 1806, they brought back maps they had drawn along their route, and information about the territory they explored. These discoveries are well documented in the Lewis and Clark diaries, versions of which are available today in most bookstores.1 Now Jef-ferson had the data he needed to decide how to take advantage of the territory, and this led to the westward expansion of the United States.

1 For the story of Lewis and Clark’s expedition, see Stephen Ambrose, Undaunted Courage (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1996).

Some projects are a bit like the Lewis and Clark expedition: They allocate budget for exploring the problem space in order to decide what might be possible and whether launching a project into this space is in fact viable.

Such an exploration is, like the historic 1804 expedition, a pure voyage of discovery. You cannot mandate what must be discovered, just as Jefferson could not instruct Lewis and Clark as to what they were to find. And whether the voyage of discovery finds anything useful is not just a matter of chance—the skill of the explorers has an effect on the outcome. Again, like Lewis and Clark, you may find that if the voyage turns up something useful, it may be very, very useful. (Your view of the last sentence may be somewhat different if you belong to one of the native nations that were displaced by the westward expansion.)

The explorers on the project team explore work in the abstract sense. They are not concerned with who is doing what, or what machines or people are used. Instead, they are examining a situation to see what ideas it provokes, what opportunities they can come up with, what the possible future state of that work could be. They are looking for opportunities and ideas that, if realized, will bring the greatest potential advantage to the host organization.

One of my clients was receiving project requests from more than one hundred different sources. Each of the requests was in a different form and level of detail, but none gave a coherent picture of what the requestor was trying to achieve. The problem was that all these potential projects contained unknown territory and needed some exploration before my client could decide on the appropriate action. And yet, the requestors were always pressing for a firm estimate of cost and a completion date.

My client decided to address the problem by introducing a short exploration of each project request. He used a checklist of exploration questions to analyze the request and to decide whether it contained the necessary answers, or whether further exploration would be necessary before he could quantify the request. Sometimes, the exploration discovered that the cost and benefits of the project did not justify going ahead.

My client has now changed his procedures such that a short exploration that answers questions on a checklist is the only way that a requested project makes it onto the project list.

—SQR

Lewis and Clark projects deliberately allocate resources to an up-front exploration of the business area to determine the potential for the project. Naturally enough, there are times when the exploration reveals that there is nothing useful that can be done to improve a situation. This discovery is a bonus—it prevents unnecessary projects from chewing up valuable resources. Other times, the exploration team finds that there is indeed an opportunity to be had and launches a project. Such opportunities have a payoff sufficient to cover the occasional barren exploration.