4. Compensation

The reader is reminded that this chapter was written originally in “normal” times—that is, before the Great Recession. The chapter’s data and cases have been updated as needed, but a number of its arguments require considerable elaboration for periods of severe economic downturn, and these will be provided in Chapter 5, “The Impact of the Great Recession: Flight to Preservation.” In that chapter, for example, we discuss in considerably greater detail how the importance of pay—especially pay increases—declined as the importance of job security increased in the recession. But pay is trivial to no one, and for quite a few workers in quite a few companies (especially those doing well), it remained central. Further, be assured that pay’s prominence will grow very rapidly once the economy recovers and job insecurity lessens.

We have also added a note to this chapter on how our arguments and recommendations apply to merit pay for teachers—a highly publicized and controversial element of the nation’s efforts to improve student performance.

Money as Seen by Workers

Workers see money as:

• Providing for their basic material needs and, ideally, to live in a manner that satisfies them.

• Providing a sense of equity—that is, receiving a fair return for their labors.

• Providing a measure—one of the major measures—of their personal achievement.

• A potent symbol of the value that the organization places on the contribution of both the workforce as a whole and of the individual employee.

Money as Seen by Employers

Employers utilize money to:

• Attract and keep the number and kinds of employees they need.

• Define the organization’s objectives, because what the organization pays for—not necessarily what it says—is what it truly wants.

• Motivate employee performance.

• Avoid labor conflict.

Although executives generally (and incorrectly) assume that “employees will never be satisfied with their pay,” they are aware that extreme dissatisfaction—a sense of great inequity—hampers the achievement of their attraction, retention, motivation, and industrial peace objectives. To avoid this, companies install pay systems that they hope prevent inordinate discontent and that can be held up as fair but ones that, at the same time, meet the organization’s desire to obtain services at the lowest overall cost. What does our research (and the research of others) show about attitudes toward pay, its determinants, and its consequences? Here are the basic findings:

• The level of compensation and the system by which it is determined and distributed are generally equal in their importance to workers.

• People want to earn as much as they can, and it is rare for workers to express that they feel overpaid. In fact, because most employees (about 80 percent) rate their performance as “above average” in their organizations, it logically follows that people would not feel overpaid.

• However, although it is the rare employee who feels overpaid, only about 26 percent (which is our “norm”) express dissatisfaction with their pay—that is, feel underpaid. Fifty-one percent of workers say they are satisfied with their pay.

• The higher the level of an employee in an organization, the greater the satisfaction with his pay. In our surveys, senior executives are usually ecstatic with their pay.

• The greater the satisfaction with pay, the higher the overall satisfaction with the organization, trust in management, and a sense that management treats the workforce as an important part of the company.

• We have shown that there is tremendous variability across companies in the percentages of employees satisfied and dissatisfied with their pay. The range is 25 percent to 78 percent satisfied and 10 percent to 58 percent dissatisfied.

• At the extremes—very low or very high actual pay—pay attitudes are determined primarily and simply by the amount of compensation. It’s difficult to be satisfied at barely subsistence levels of pay, or for one’s complaints to be taken seriously, even by one’s self, about pay when earning millions. Between those extremes, the degree of satisfaction with pay is very much a result of comparison—with others, with one’s history, with one’s perceived performance, with the cost of living, and so on. In roughly the order of their importance, here are what we find to be the major determinants of pay satisfaction:

– How well the organization pays relative to what employees believe other organizations pay for similar work.

– Whether pay increases over time and how increases in one year compare to increases in past years. Tenure, whether explicitly acknowledged or not, is therefore a major criterion people use to judge the fairness of their pay.

– The extent to which pay increases are believed to reflect the employee’s actual contribution (performance) and potential contribution (what the employee is able to do because of his training and skills and expanding experience over time).

– The extent to which pay increases reflect increases in the cost of living. During times of high inflation, the cost of living becomes an all-consuming issue.

– The perceived generosity of nonwage benefits, especially medical insurance. As healthcare and medical-insurance costs have skyrocketed, employees have increasingly come to see pay and their benefits costs as offsetting one another. In the minds of many, the increase in medical costs and premiums offset pay increases; therefore, they may see the latter as little or no increase at all (“just barely breaking even, if that”). In general, then, the more generous the medical benefit, the greater the satisfaction with pay.

– How well the employee is paid compared to what other employees in the company, especially those at similar skill levels, are believed to earn.

– Company profitability, or how much the company is believed to be able to pay.

– The discrepancy between the compensation of the general workforce and that of senior management. A large discrepancy is not an issue when the organization is doing well and the workers feel that they are also benefiting from that success: “Let him earn as much as he wants—he deserves it and it’s been good for me.”

We describe in this book the conditions that distinguish enthusiastic from unenthusiastic employees. Pay is vital in that respect, both substantively—it provides the material wherewithal for life—and symbolically—it is a measure of respect, achievement, and the equitable distribution of the financial returns of the enterprise. As shown in the previous chapter, a sense of equity—of which pay is a key component—acts something like a “gate” to the functioning of achievement and camaraderie. Without a feeling of being treated fairly, the impact of the latter two is greatly diminished. The power of pay is further amplified by the fact that, in and of itself, it is a satisfier of both the equity and achievement needs.

Pay also affects the fundamental credibility of an organization in the eyes of its workers: is it putting its money where its mouth is? For example, is an organization that does well and that claims that its employees are “its most important asset” seen as nickel-and-diming the workforce when it comes to pay? Is a stated emphasis on product quality and customer service made real with rewards for those who produce high quality and provide good customer service? Our surveys frequently reveal large gaps between words and deeds, with employees often defining “deeds” in terms of how an organization pays.

Typically, management bases its evaluation of its pay-system effectiveness on “objective” data, such as labor cost percentages and trends, salary surveys, and formal job evaluations. Aside from the question of the validity of such data, they beg the fundamental question, “How do workers see things?” For example, if they see no pay for performance, there is no pay for performance. To reward and motivate, pay for performance must be seen by workers to exist. As we now explore pay attitudes and their effects in detail, keep in mind the basic proposition that management’s views of its policies—pay fairness, its relationship to performance, and so on—are irrelevant (except for management’s views of its own pay).

In thinking about pay and formulating recommendations for effective compensation policies, it is useful to distinguish the level of pay from the way it is distributed, especially in relation to performance.

Levels of Pay

We mentioned previously that it is virtually impossible for companies to inspire loyalty and commitment in workers who are treated as disposable commodities. Similarly, it is difficult for a company to be able to achieve loyalty and commitment from its workers when it’s seen as one of the lower-paying companies (especially in relation to its competition and its profitability). Still, for many workers, job security comes first; when a choice has to be made, workers will usually moderate their pay demands to preserve their jobs. But pay is a close second.

Contrary to popular belief, employees don’t expect wildly generous pay for their labors. In fact, they would likely question the motives or competence of management if pay were astonishingly high. Therefore, we must differentiate between the wish for a lot of money and workers’ views of what is reasonable and fair. They are capable of separating wishes and fantasies from realistic expectations. Most workers express satisfaction with pay that they consider to be “competitive” and great satisfaction with pay they consider to be even a few percentage points above the competition. A few percentage points can mean hundreds of dollars, and that’s both materially and psychologically significant to the average employee.

A few examples of individual comments might help give meaning to our argument. These comments are responses to the question, “What do you like most about working here?” We will soon show how employees dissatisfied with their pay express their views.

What I like most about the company is that the pay is decent.

The medical benefits are good, and the pay is comparable to other companies.

I like the pay that I receive here. It is the highest, although by a slim margin, among other companies in the same field. The company shows it values its employees.

The opportunity to contribute to a high-class business such as this one and make a pretty decent paycheck in the process.

The pay is above average for the type of work we do.

I think that the benefits are outstanding and the pay is very reasonable in today’s workplace. I also appreciate that the company reimburses my tuition costs.

Unfortunately, the same principle of differentiation holds when pay is below that of the competition: just a few percentage points can count greatly. This principle also comes into play in how workers react to pay increases. An increase that’s even slightly below the rise in the cost of living—when that rise has been significant—is generally considered a pay decrease. Most workers know the rate of inflation, especially in times of high inflation, down to the last decimal point.

Furthermore, workers are not happy when a pay increase they have just received is less than increases they previously received. This can also be viewed as a decrease or, at least, a disappointment.

To workers, it is critical that their standard of living not fall (as is the case when pay does not keep up with inflation), and it’s important that the rate at which they move ahead does not decline. These might appear to be small, and even trivial, concerns to highly paid executives, but they are important to the masses of workers who count every dollar. Of course, it is not just a material issue because pay has great symbolic value to workers; it signifies respect, achievement, and equity. Therefore, attitudes toward pay and pay increases have major consequences for pay-for-performance systems. For example, if a “merit” increase is not felt to be an increase because it does not keep up with inflation (in fact, if it is viewed as a decrease), how credible, satisfying, and motivating will the merit pay system be for that employee? We discuss merit pay in detail later in this chapter.

The opinions workers have of their pay are also greatly affected by how they see their organization’s financial condition. We have repeatedly asserted that the overwhelming majority of workers are realistic and reasonable. Therefore, they expect more generous pay and pay increases when times are good and less when times are bad. When times are truly bad, they may even be willing to accept pay cuts, especially if those seem necessary to avoid or reduce layoffs.

But, acceptance of pay cuts—or reduced increases or no increases—as legitimate depends on whether employees trust their management. Trust, which is often lacking, is in this case a function of:

• The overall views that workers have, based on the totality of their experiences in an organization, of management’s credibility and its interest in the well-being of the workforce

• The degree to which sacrifice in bad times is seen as shared from the top to the bottom of the organization

When trust is present, the kind of support an organization can receive from its workers is absolutely amazing.

Here are some additional open-ended comments that demonstrate the various points we have made about pay. They are responses to the question, “Now, what do you like least about working here?” We have included an abundance of comments about pay so that the reader gets a full appreciation of what is on employees’ minds when they are unhappy on this subject of such importance to them:

I have no trust at all in the brass and what they tell us. This company is doing well now. Why is so little trickling down?

Additional workloads that are constantly placed on you and really no compensation in pay. We could be equal in pay to other companies, but we do about 12 times the amount of work.

I don’t like the fact the pay in my area is not adjusted according to cost of living at all. We’ve fallen behind.

Other employers are offering somewhat higher pay. I can’t continue to work here when I know there are better opportunities.

The worst thing is working and doing so many tasks at work and not getting compensated for it. The pay here really sucks in that regard. It’s at least 5 percent below what other companies pay.

Medical and dental plans increase much more each year than the pay does. Therefore, we are not increasing our pay but decreasing it.

We work for a multibillion dollar company and still cannot pay for rent, utilities, and food. With overtime, I cannot support my family of three. Shame on you!

The pay scale and raises are also disgusting. I have been here for 4 years and barely get paid $9.00 an hour. New employees here are currently hired here at $10.00 (on the average) an hour.

Being able to make ends meet. Salary needs to be more competitive. I don’t feel that we are paid enough to do the job that we do. Stop with the balloons and silly games and pay us instead. Most people today do not have the luxury of two incomes.

The pay rate for employees is below industry average. No wonder the turnover rate is so high here.

The fact that my benefits are going up, my co-pays are increasing, and my prescriptions cost more yet we cannot get a decent percentage in our merit raises. A cost of living increase would be appropriate, even a couple percent.

This company does not even keep up with the cost of living index; thus, any annual raise is no raise at all. In essence, the longer you are at this company, you are actually staying the same or going backwards pay wise. I feel this is one of the main reasons good, qualified people leave the company.

Our take-home pay should be much better. This company makes billions. Give us a bigger slice of the pie; there is no you without us.

I agree with the changes to incentive pay plan. It makes sense that if profits are down that we make adjustments to curb the monthly take by sales associates... So why is this information presented to us with the conviction of a parent trying to convince their kid that Santa’s still real? “These changes are a good thing.” “These benefit you.” Really? All that said, I agree with the need for the changes, but what’s with the lying? In fact, that still remains my biggest issue: the dishonesty.

I feel that I have been lied to on a few occasions, one regarding raises being offered. I was told “absolutely, you will be eligible for a raise on the same schedule as the rest of [the company].” When I voiced my concern, I was told, “I don’t think there is anything we can do.” I was never asked what I would consider an acceptable raise; I was just flat out told no, even though my pay was less than the other managers of my level.

I quite honestly don’t believe anything my senior leaders tell me regarding pay or bonuses. Their words conflict with what my immediate manager tells me. They also conflict with common sense. And finally, their words have often later proven to conflict with their actions.

The last two years I received a 3% raise, which does not even keep pace with inflation. I have never worked harder and given more and received so little in return, and yes my reviews have all been highly positive. Additionally, I do not trust the leaders of this company because they are managing for quarterly results for Wall Street and care very little for the associates or the customers.

What does motivate really mean? To me, it means that I would get something in return for going above and beyond, either material or immaterial. If I do go beyond, not only do I get nothing, but my manager takes credit for whatever was accomplished.

With perks being slowly taken away one by one from the employees, you can’t help but wonder where it is going to stop, if ever. It would be one thing if things were taken away from us as employees equally, across the board, but it is not. The announcement of no bonuses or raises was also, quite frankly, a piss off. Why should the employees have to suffer for the mistakes and bad decisions made by the top executives who have little or no knowledge of the way the company works from a customer point of view?

Now, what is the impact of pay level on organization performance, such as profitability? One would think that, everything else being equal, the higher the pay, the greater the cost to a company and therefore the smaller the profits. We have already commented on the relationship between pay and enthusiasm, so there is some reason to believe that the relationship between pay and cost would by no means be perfect—the positive effect on employee morale and performance should offset to some extent the impact of labor costs on profits. But it goes further than that.

In economics, there is a body of theory, termed “efficiency wage theory,” that deals with this issue. Based on observations such as the fact that higher pay rates are found in more profitable industries, the theory states that compensation above what a firm has to pay (that is, above the “competitive market-clearing wage”) drives up labor costs but also produces benefits, such as greater work effort, that increase output and revenue for the firm. In his article “Can Wage Increases Pay for Themselves?,” David I. Levine concludes that “...business units that increase their relative wages for workers of similar human capital [skill level, training, etc.] have productivity gains approximately large enough to pay for themselves.” He found that, in units where wages declined over a three-year period (factoring in inflation), worker output increased 2 percent. Where wages increased, worker output grew by 12 percent.1

The research evidence points to four explanations for the relationship between wages and productivity:

• Worker reciprocity and morale. The “gift” of higher wages from the employer is reciprocated by a “gift” from workers of higher productivity. This is in line with what we have said about the impact of morale on performance. Employee performance over the long term, of course, is not just a matter of productivity, but also the cost savings and profits generated by higher quality, better customer service, and so on.

• Lower turnover. Higher paying companies lose fewer people, so they have lower turnover-related costs, especially for recruitment and training.

• Decrease in “shirking.” For those employees not inclined to work hard, higher pay means that dismissal is a greater penalty than if the job paid less.

• A superior pool of job applicants. Higher pay attracts a larger number of better job applicants from which to choose.

All four factors appear to play a role.

Obviously, there’s a limit to the relationship between high wages and productivity. Levine found that the relationship holds less strongly in firms with large percentages of unionized workers. In those companies, he suggests, wages have gone beyond what could be made up by increased productivity.

An important practical lesson of the research on wages is the error of confusing labor rates with labor costs. Labor costs are a function not just of how much is paid to workers—that’s the rate—but also how much workers produce. The correct measure of the labor cost to organizations is the ratio of wages to productivity, what economists call unit labor costs (ULCs). Low wages and low productivity can offset each other in terms of their effects on ULCs, potentially making labor expensive when wages are low. In this connection, it has long been observed that the nations with the highest wage rates tend to be the most productive. Although low-wage countries still have a competitive advantage, that advantage is cut in half, on the average, when comparing ULCs.

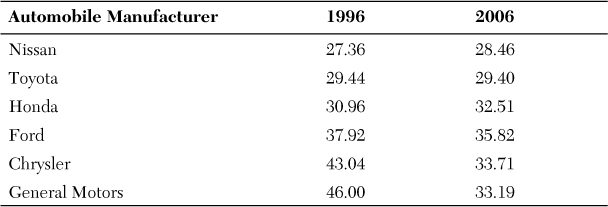

The analysis also applies to individual companies within a country where there are large differences in productivity. For example, Japanese automobile manufacturers in the United States long had a huge labor-cost advantage over their American-owned counterparts, despite similar wage rates, because they were much more productive. Table 4-1 shows the historic difference, measured in 1996 (the data available for the first edition) and again in 2006, between the labor hours that North American automobile manufacturers require to produce a vehicle.2 As we can see, although an advantage remains ten years later, it has diminished significantly.

Differences in labor cost say little about quality and other key aspects of company success. Few systematic studies specifically correlate wage rates with product quality, but the research available suggests a positive correlation.4 High wage rates should affect quality in much the same way they affect productivity (for example, by allowing the organization to attract and retain more highly skilled workers that will do higher quality work). That was the reasoning of the president of Wendy’s, who was confronted with soaring costs and declining sales in 1986:

“[I] found we had lost our focus on—people. We had such fear in our hearts about numbers, about the power of computer printouts and going by the book, we’d managed to lose sight of our customers and employees.... A number of basic changes were made, including significant improvements in compensation...and benefits.... Our turnover rate for [general managers] fell to 20 percent in 1991 from 39 percent in 1989, and turnover among co- and assistant managers dropped to 37 percent from 60 percent—among the lowest in the business. With a stable—and able—workforce, sales began to pick up as well.”5

The Costco Wholesale Corporation is a warehouse-retailer that, despite its fame and popularity, has frequently been criticized by Wall Street analysts for the generosity of its employee pay and benefits policies. “From the perspective of investors, Costco’s benefits are overly generous,” says Bill Dreher, retailing analyst with Deutsche Bank Securities Inc. “Public companies need to care for shareholders first. Costco runs its business like it is a private company.”6 “Whatever goes to employees comes out of the pockets of shareholders,” claims Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. analyst Ian Gordon.7

In a recent personal communication, Jeff Elliott, Costco’s Assistant Vice President of Financial Planning and Investor Relations, informed us that the average wage of U.S.-based Costco employees is $21.50 per hour (not including medical and other benefits), and that employees receive, in addition, twice-a-year bonuses, ranging from $2,500 to $4,000 each period. The average annual U.S.-based Costco employee’s wage, therefore, is approximately $45,000 for full-time employees. 90 percent of U.S. employees are eligible for medical benefits, and the company pays about 92 percent of all employee medical costs, including dental and vision. The company also contributes to a 401(k) plan for each employee and does so whether or not the employee makes a contribution. The annual contribution, based on years of service, ranges from 3 percent to 9 percent of employees’ annual compensation. “We recruit heavily from college campuses, and younger associates may not value their retirement savings as they should, so we make a contribution for them regardless,” Mr. Elliott said.

How does this contrast with the wages and benefits provided by other retailers? The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) reported the average hourly wage for retail workers in Q1–Q3 of 2012 to be $13.29, whereas the National Retail Federation reported on its website that in 2010 the average hourly wage in the industry was $12.97. These are substantially lower than the rate for Costco ($21.50), but the best comparison would be a similar retail company, such as Sam’s Club, a division of Walmart. Unfortunately, Walmart does not break out Sam’s Club wage data, and we have not been able to locate reliable wage information for Walmart as a whole after 2006. (There are a number of more recent figures published, but these tend to be from Walmart’s many and vociferous critics, and we have no idea how reliable those data are.) Coleman-Lochner reported that in 2006 a Walmart employee’s average hourly wage was $10.11.8 The BLS, in the same year, reported hourly wages and salaries in the retail sector to be $11.85. The Costco average hourly wage that year was $17.00.

With regard to benefits, BLS reports that 63 percent of all retail workers had access to healthcare benefits in 2012, and a leading payroll processing company found that 70 percent of the premiums were being paid by the employer.9 Greenhouse of the New York Times reported that fewer than half of Walmart’s workers had benefits coverage in 2005, and Walmart paid just 33 percent of those premiums.10

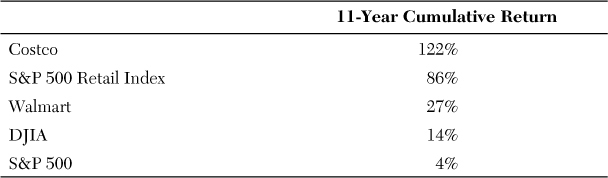

So who is Costco being run for anyhow? The employees? One good way of determining who profits from Costco, besides employees, is the company’s stock market performance. We see in Table 4-2 that Costco outperforms the major indices, and Walmart, by substantial margins.

It does not appear that the Costco stockholders have suffered, at least not comparatively.

We make no claim that Costco’s—or any company’s—performance is a result solely of how employees are treated. Senior management’s business competence and business strategy are crucial for success, and Costco’s strategy—such as its membership model and limiting the number of items it stocks—has been lauded by many students of business.

But from the point of view of Jim Sinegal, the company’s cofounder and former CEO, how employees are treated is critical and, indeed, is considered a central element of its business strategy. “Imagine,” he said in 2006, “that you have 120,000 loyal ambassadors out there who are constantly saying good things about Costco. It has to be a significant advantage for you.... Paying good wages and keeping your people working with you is very good business.... Why shouldn’t employees have the right to good wages and good careers?”11 And, says Mr. Sinegal, “It absolutely makes good business sense.... Most people agree that we’re the lowest cost producer. Yet we pay the highest wages. So it must mean we get better productivity. It’s axiomatic in our business—you get what you pay for.”12 In 2012, operating income per full-time equivalent employee was $28,800 at Costco versus $17,400 for Sam’s Club.

Costco’s current CEO, Craig Jelinek, succeeded Sinegal in 2012 and, in a recent statement, expressed a similar perspective: “Most good CEOs serve their people; their people don’t serve them. That’s what it’s all about. If you work with your people and give opportunities for your people to grow and help them succeed in what they want to accomplish, only good things happen for you. At Costco, we know that paying employees good wages makes good sense for business. Instead of minimizing wages, we know it’s a lot more profitable in the long term to minimize employee turnover and maximize employee productivity, commitment, and loyalty.”13

Yes, Costco executives are crazy—like foxes. Here are some additional data: BLS reported that in 2011, the annual quit rate for retail nationwide was about 26.5 percent. It is currently less than 11 percent at Costco. “Shrinkage” (essentially, theft) is less than ¼ of 1 percent at Costco, six times lower than the national average, which is approximately 1.5 percent.

The evidence clearly suggests that the normal inclination of many executives to pay as little as possible is often misguided. Organizations need to strive to compensate their workers well—even above the competition to the extent affordable. The edge over the competition, however, does not have to be in base pay. We discuss variable pay later in this chapter, such as gainsharing bonuses, which has the advantage of providing an organization with a mechanism that adjusts compensation to the performance of the workforce and the fortunes of the business.

Paying for Performance

We come now to the system by which pay is distributed, especially as it relates to performance.

In our preceding discussion, employee performance was treated as a “dependent variable”—that is, as an effect of the level of pay. In Costco, for example, we—and its senior management—argue that higher pay can mean higher performance. Let’s turn that around and think of it in the more customary way—that is, as an “independent variable”: the way employees’ performance affects their pay.

Most organizations have a pay-for-performance system of one kind or the other. The organizations that don’t—or have it for just a segment of the workforce—tend to be in unionized environments and government agencies. In those cases, pay increases are negotiated or are simply the consequence of tenure and “in-grade” promotions (promotions where compensation increases, but job responsibilities basically do not).

First, let’s consider systems meant to pay employees for their individual performance. The two most common are piecework and merit pay. Both sound terrific—they certainly fit the American ideology of individual effort and reward—but they have been found to be seriously wanting in practice.

Piecework

As the name says, employees working under this system are paid by the piece. The occupations to which this system is most typically applied are production workers and salespersons. For the latter, the “piece” is the amount of the sale, and the system is a commission plan. We first discuss piecework as applied to production workers.

Piecework in a production environment appears to be eminently sensible and fair because it aims to tie compensation directly to performance, and the measure of performance is objective (pieces produced that can be counted). The reality, however, is that disputes about these systems are extremely common. In many unionized environments using piecework, the system is the largest single source of employee grievances. For this and other reasons, the percentage of organizations that employ piecework has been declining.14

What are the issues? In factories, the key problems concern the way productivity standards are developed on which the piece pay rates are based. The standards define what is expected of the workers: the number of pieces per unit of time (hour, day, and so on). Typically, industrial engineers who rely on time study or some form of predetermined (synthetic) data develop the standards. The organization decides—or, in negotiation with the union agrees—on what a fair wage would be for a job if the employee meets the standards. The piece rate, then, is the standard number of pieces per time period divided into the agreed-upon fair pay for that time period. For example, if the standard is 100 pieces per day and the fair pay is $100 per day, the piece rate would be $1. Workers could earn more than $100 per day if they produced more than 100 pieces.

This measurement approach generates two serious problems. First, there is the question of the fairness or the accuracy of the standards. Typically, workers complain that they are unreasonably high. In union shops, these often become the subject of an endless stream of grievances and negotiations. The “objectivity” of the standards—a key assumption of the system—is, obviously, a matter of considerable dispute.

The second issue is equally important, although it’s less commented on. The standard is production expected using a particular method. If a worker were to think of a better method for doing the job—which would increase her production, say, by 25 percent—the production expected from her (the “standard”) would be increased by 25 percent, and she would have to produce 25 percent more to earn the same income as before. Otherwise, she might be earning “too much.” In effect, the company has cut how much she is paid per piece and has pocketed the savings. The term “piecework,” therefore, is in part a misnomer. The employee is not being paid for pieces produced per se, no matter what the method; she is being paid for pieces produced with a particular work method. This has two consequences:

1. There is little or no motivation for employees to make method improvements that increase the overall output of their jobs. It is true that workers, after some time on the job, usually discover how to improve methods, but these improvements are typically kept to themselves because revealing them brings no reward; in fact, it is seen as punishing. This represents an enormous waste of an extremely important resource—the talent, the initiative, and the creativity of the workforce—and is antithetical to improvement goals. Although the system is designed to get workers up to the standards, it discourages them from beating the standards. The losses in productivity that are engendered are large.

2. By treating workers as if the only thing that matters is their physical exertion, we remove from them a major source of achievement and self-esteem—namely, the opportunity to demonstrate their ability to think. We set up systems in which we have specialists in thinking: the methods engineers. Their job is to develop “best methods” by which the workers should get their jobs done. All we ask of workers is that they follow orders and work hard. But anyone familiar with such factories knows that workers can be mighty creative as they go about making life difficult for line management and its staff representatives: fooling the time-study man when being studied, submitting formal grievances whenever possible, and hiding new methods.

The theory of piecework—that a straight-line relationship exists between the wages a worker can earn and the effort he is willing to expend on the job—is therefore seriously flawed. An additional important problem for such systems is the effect that they have on group cohesiveness. It has often been observed that individual incentives discourage teamwork because each employee is out for himself. Although this is true in many white-collar occupations, the opposite is often the case on the factory floor. The systems often increase cohesiveness among workers, but only in opposition to management. Workgroups set their own production norms and expect their members to adhere to them. The worker exceeding the norm is the rate buster (that’s one of the more polite terms), and he does not have an easy life on the factory floor.

Most production workers are not like most salespeople for whom individual competition on the job is normal and a pathway to a sense of achievement. We elaborate on that difference later in this chapter.

In factories, the piecework system results in a continual tug-of-war between labor and management: workers and workgroups pressuring to hold down production and management pressuring to increase it. This seems to contradict our earlier optimistic view of workers and worker motivation, but keep in mind that workers’ attitudes and behavior are a function of not just who they are, but how they are treated. In the situations we have described, workers see deceiving management, submitting grievances, and restricting production as means to survive in the face of a management that’s bent on turning its workplace into a sweatshop and limiting its pay opportunities. That’s usually not the way management sees it, but that’s the way workers see it.

We have focused on the employee relations and productivity consequences of piecework. There is another issue, one that afflicts many pay-for-performance systems. A company that seeks to pay for performance must define what performance means. Part of the attractiveness of piecework (whether on the production floor or in sales) is that it relies on objective measures. (Things get counted.) So, the definition of performance is often narrowly limited to what is countable. Because people focus on what is measured and rewarded, we often find workers cutting corners to produce what is expected. Workers might run machines at higher speeds than instructed, the quality of the output might be sacrificed, and so on. This is not only an attempt to reach the expected production levels, it is also part of the game, the tug-of-war, between a workforce and management. “Okay, you want x number of pieces, we’ll give it to you and wait until the junk comes back!” Management has to then introduce additional controls and penalties to help ensure quality and protect the equipment. It’s all expensive and, as we will show, needless.

Is piecework ever appropriate? Yes, if it’s applied in the right conditions and to the right people. The problems and costs of piecework tend to be least when the tasks are simple, repetitive, can be done independently, and when management genuinely responds to workers’ concerns about wages and the accuracy of the standards. Complex, nonrepetitive jobs generate the most disputes about standards, and the impact of individual incentives on teamwork is largely irrelevant if teamwork is rarely needed. Coupling those conditions with a management that has a genuine concern for its employees’ well-being can make individual piecework the most effective system. A good example of this is Levi Strauss, a progressive management that switched from individual piecework to group-based incentives and suffered a decline in production.

And some workers prefer an individual piecework system. Research done in the 1950s by William F. Whyte15 found that these workers tend to be socially isolated from their co-workers, owners of their own homes, and Republicans. Making money has a moral dimension for them, providing proof that they work hard. They are the rate busters—disliked, but uninfluenced, by their fellow workers, and beloved by management.

Salespeople are similar to the rate busters in their compensation preferences. There are differences between the two groups in their personality traits and abilities—on the average, salespeople have much stronger social and communications needs and skills—but great similarity on traits such as independence, assertiveness, confidence in their ability to achieve high earnings, and high earnings serving as a major source of self-esteem. The salesperson personality profile fits the sales job perfectly and is, of course, why those people gravitate to that type of work. It is also why a compensation plan that is oriented to individual rewards attracts them (the sales commission plan). For most of them, it would be frustrating to work in any other environment and, with few exceptions—such as when teamwork is absolutely essential for high performance—that is the incentive plan recommended for them.

This is not to say that individual incentives in sales do not present problems, some of them similar to what we find in factories. Sharp disagreements can occur about the fairness of quotas and commissions, the amount of differential payment for different products, and the handling of charge-backs. A frequent and major concern is the way high productivity and earnings are dealt with. As with factory workers, salespeople are often faced with disincentives to high performance because, if they produce and earn a lot, their quota is raised or their territory reduced. Therefore, salespeople seem to be continually negotiating with management about the terms of their commission plans.

Despite the problems, our survey data show that professional salespeople are significantly more positive toward their compensation than non-management employees in general. This is so because, for one, an incentive compensation system fits their personalities and objectives. Second, they tend to be among the more highly paid employee populations. They are paid well because their performance is seen as among the most essential to the success of business: they bring in the money! Finally, because salespeople are so vital, they have a lot of bargaining power—especially the more successful salespeople—and management usually makes arrangements to keep them at least reasonably happy.

Besides matters of equity, sales-compensation plans can generate organizational issues, such as the deleterious effect individual commissions might have on needed teamwork and the tenuousness of the ties of salespeople to their organizations when a large proportion of their compensation is commission (rather than salary). Over the years, these problems have been recognized and, increasingly, when teamwork is essential, group incentives have become the norm. Today, most salespeople are paid a base salary with commission averaging about 10–35 percent of their total compensation.

Merit Pay

The great majority of salaried (as opposed to hourly) workers in the United States work under some form of “merit pay” plan. One of the major differences between merit pay and piecework is that in the former, pay adjustments are made not directly and immediately on the basis of production; instead, they are made on the basis of the boss’s subjective evaluation of the employee’s performance over a period of time (usually a year).

Among the less positively rated areas in surveys is the degree to which organizations that profess to pay for individual performance are seen as actually doing so. Our norm on perceived pay for performance is 40 percent favorable and 40 percent unfavorable. In other words, despite the theoretical attractiveness of paying for “merit,” the pay-for-performance systems in place are not particularly credible for quite large numbers of workers. Part of the problem stems from the boss’s evaluation of the employee’s performance. It is not that employees disagree with the evaluations; in fact, our research shows that there is considerable agreement.16 Instead, it is that the evaluations are biased upward. That’s why so many employees agree with them! It is only slightly facetious to say that, in effect, merit increases determine the performance evaluations rather than the other way around. That is, to avoid unpleasantness in their performance-evaluation sessions, many managers tend to rate just about everyone highly (at least “satisfactory” or its equivalent). The tendency would be less pronounced if pay increases were not tied to the evaluations but, because the latter mean money, the positive bias is strong indeed.

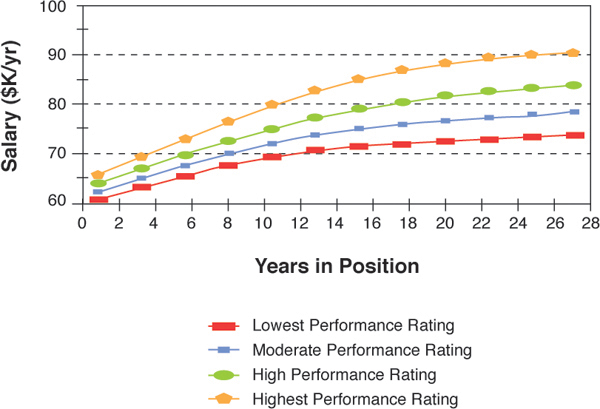

The problem of biased evaluations is magnified by the systems through which pay increases are supposed to be related to performance. A common approach is to use a “grid.” Figure 4-1 shows an example of this grid.

The vertical axis of the grid defines the pay range of the job (from minimum to maximum). The line graphs represent employees at different levels of evaluated performance. The major objectives of the grid are to differentiate the increases of employees with different levels of performance, while containing salary increase costs. These objectives are, in practice, somewhat contradictory. For example, newer employees are typically at the low end of the range no matter what their performance. Also, the salary increases of employees at the upper end of the range level off no matter what their performance. Both outcomes help contain costs but greatly dilute the relationship between salary increases and performance. Technically, the organization is paying for performance with this system, but taking into account position in range. Unfortunately, employees don’t perform the mental gymnastics required to allow them to feel that they have indeed been rewarded for their performance. An employee doesn’t say, “It’s okay that I received a smaller increase this year than last year, even though my performance was the same. After all, my pay is now higher in the range.” It would take a saint to accept that reasoning—and a clairvoyant one because in many companies employees are told little about what’s going on concerning ranges, grids, and so on.

The following further compound the problem:

• Budgets. In recent years, organizations’ salary increase budgets have been approximately 2–3 percent. These budgets are especially important to control because they are not one-time costs: a salary increase becomes part of an employee’s base salary and is therefore an expenditure as long as the employee stays with the company. But managers with very small salary increase budgets cannot make a lot of differentiation among employees without angering those who are not outstanding, but still satisfactory, performers.

• Change. Salary increase budgets change year to year depending on how much the organization believes it can afford to pay. The amount of increase for a given level of performance will therefore change with the budget, adding to the ambiguity and perceived arbitrariness of the relationship between an employee’s performance and the size of her salary increase.

• Inflation. We have said that when an increase does not exceed the rate of inflation, it is usually not viewed as an increase; if it is less than inflation, it can be felt as a decrease. If, say, inflation is 3 percent and managers with a 3 percent increase budget are asked to differentiate increases on the basis of performance, some—maybe half—of their employees will feel that their pay has been cut. Most of these employees are likely to be wholly satisfactory performers. Furthermore, companies almost never distinguish for employees the amount of the increase that is due to the rise in the cost of living, which makes the performance-pay relationship even more ambiguous. Market-based increases to meet the competition—again, rarely distinguished from merit increases—add to the problem.

We can now understand why it is so difficult for many employees to see a relationship between their pay and their performance. It comes down to this: most managers very much want to pay for performance, but to get their day-to-day management jobs done, they tend also to be concerned with minimizing employee discontent. The merit pay system, coupled with their own discomfort at delivering unpleasant news, makes it difficult to reward as they truly believe they should. Therefore, many managers focus on figuring out the size of the increase for each employee that results in the fewest problems for them. They know, for example, who is likely to complain and who is likely to accept their word that, “This is really a tough year for the company. I don’t have much money to spread around; I’m doing the best I can.” They try to make sure that all—or almost all—of their employees receive as much of an increase as their budgets allow and then give some more to those who are likely to give them a particularly hard time. This minimizes differentiation among employees, with the exception of the “squeaky wheels” and, sometimes, those whose performance is truly and visibly inadequate.

Managers also seek ways around the system: for employees who are likely to leave the organization (and whose leaving would be a loss), or who might raise hell, or who are, indeed, truly outstanding performers, they might seek “exceptions” (a larger increase than the grid suggests), or in-grade promotions, or position re-evaluations to move the jobs to higher levels. It depends on what is possible and what will least frustrate other employees and those in a position of power.

The result is a half-baked version of pay for performance with which not many are satisfied, but one that normally doesn’t have serious repercussions: people “live with it.” Our statistical studies of organizations’ merit pay systems show that tenure, not performance, is by far the highest correlate of employee pay within a job grade. That is, the net effect of the system, and the machinations that surround it, is not that much different from approaches that base pay exclusively on seniority. Only, it is less clear.

Recommendations

We have been hard on individual pay-for-performance systems. It is difficult to argue with approaches that are designed to pay individuals for their performance—it’s almost un-American to do so—but the fact is that they tend to have numerous and severe problems. For many companies, they become bureaucratic and administrative nightmares without doing much to further their basic goal: rewarding people for their performance.

Is there anything better? Yes.

The better alternative is not to junk pay for performance and simply pay all employees in a particular job grade wherever they work the same or compensate by seniority. Those should be avoided because, when implemented properly, pay for performance can indeed be very positive and powerful in that it does the following:

• Gives financial reward to employees for reasons of both equity (sharing in the organization’s financial returns) and recognition.

• Gives direction to employees by aligning rewards with the organization’s goals and objectives. Pay is probably the most salient communicator of organizational goals.

• Can provide a mechanism for adjusting compensation costs to the ability of the organization to pay.

It should therefore be clear that we are in no way opposed to rewards based on performance. The question is, how? We know that organizations—and segments of organizations—differ, so no one approach will be appropriate for all. Here are the basic principles we believe should guide the design of pay-for-performance plans and concrete illustrations of how these have been put into practice. The principles are:

• Employee compensation should include both base pay and variable pay.

• Base pay should be competitive and should keep up with inflation.

• Variable pay is on top of base pay and should, for the large majority of employees, be based on the performance of groups rather than individuals.

• Variable pay should be distributed as a percentage of the employee’s base salary.

• Individual performance should be rewarded by “honors.”

• Variable pay versus merit salary increases. The basic structure we recommend is one in which employees receive base salary or wages plus variable pay that is geared to performance. This is similar to piecework systems where employees receive base pay plus an amount per piece; the difference, as we shall see, resides in the way we recommend performance be measured (as a group rather than on an individual basis).

Using a base-plus-variable-pay approach is different from merit pay. A merit pay increase becomes part of the employee’s salary—it is, in effect, an annuity cost for the organization. Variable compensation, on the other hand, is tied to the organization’s ability to pay, such as to its profitability or to cost savings that have been achieved. This is an enormous advantage because it makes payroll costs much easier to control. It might not seem like a plus for employees because the extra compensation does not become part of their salaries. But employees’ base pay will increase anyway to compensate for inflation, and most people are pleased to know that. The recognition and reward portion of their pay is clear, which eliminates the ambiguity of the merit pay system where performance-, cost-of-living-, and market-based increases are confounded.

• Group versus individual performance. For the great majority of the workforce, we recommend that variable pay be based on group, rather than individual, performance. We have two reasons for this preference. First, performance of a group is usually easier to measure; it’s more objective and credible than that of an individual. At the total company level, for example, contrast the relatively objective measurement of company profit with the highly subjective judgments about the contributions of individual senior executives to that profit. In a cost center, such as a manufacturing plant, contrast measuring the cost performance of a plant as a whole with measuring the efficiency of individual workers. We saw how individual production standards can generate a flood of grievances about their accuracy. If the goal is to distribute financial rewards among workers according to their individual performance, workers must be compared to each other. How is the performance of a maintenance person to be compared with a production worker? Not easily.

The second reason for preferring group measurement is that performance almost always depends not just on individual capabilities and effort but also on teamwork. The profound power of pay should be used to encourage, not discourage, teamwork and individually-based plans do little, at best, to stimulate cooperation and they can produce dysfunctional competition and conflict. The teamwork that group pay plans encourage has two positive effects: it boosts performance in and of itself, and it satisfies workers’ camaraderie needs, which adds to their enthusiasm and performance.

How about the “shirkers”—those who prefer not to work hard? Doesn’t a group approach give them an out, a way to be rewarded for not much effort? Research shows exactly the opposite: under a well-administered group pay plan, the responsibility for dealing with workers who won’t work is shouldered in part by the work group. Shirkers hurt group performance and, therefore, workers’ pay, and a group norm develops that puts pressure on low producers to produce. This is almost invariably more effective than management dealing with the problem alone. Aside from shirkers are those employees who are motivated to perform but who need performance coaching or other kinds of assistance. Group-based plans strongly reinforce the natural desire of employees to provide such help to their co-workers.

How about the truly outstanding performers? Isn’t a group payment approach unfair to them? Our experience with employees working under these plans reveals few problems in this respect. The reason is that these outstanding performers are contributing significantly to the well-being of the entire group and receive a great deal of recognition from their co-workers. This contrasts with the reactions of workers to “rate busters” working under piecework. In those cases, high individual performance is seen as detrimental to the group’s interests. We will suggest later, however, that the informal recognition that high performers receive under group plans be supplemented with individual formal awards.

What are the group compensation plans that are available to organizations? Countless plans exist, but almost all can be grouped into three major categories: stock ownership, profit sharing, and gainsharing. Which one(s) to choose? Here are the criteria that should govern the selection of a plan. A plan is more effective to the extent that:

– It steers employee performance to the achievement of important organizational goals.

– It allows employees to see the impact of their performance and to see that impact in a timely way.

– The optimal achievement of the goals requires teamwork as well as individual effort.

– The performance measures are clear and credible.

– The financial return to employees is, in their eyes, substantial.

– The plan serves to satisfy employees’ equity, achievement, and camaraderie needs.

– The plan enhances employees’ identification with the organization.

Of all the plans, gainsharing meets the above goals to the greatest extent by far. But it, too, has gaps; therefore, for most organizations, a combination of the plans is preferable. The following are descriptions of the plans and the key research findings on their effects.

Employee Stock Ownership

The ownership by employees of stock takes three basic forms: employee stock ownership plans (ESOPs), pension assets invested in employer stock, and stock owned directly in the company through stock option and stock purchase plans. Combining the three forms of owning stock, it is estimated that about one-fifth of American workers hold stock in the company in which they work.

Employee stock ownership has strong proponents, some almost evangelical in their advocacy. Their arguments are based on both financial and motivational considerations. Stock ownership is touted as a good way for employees to increase their assets through participation in the growth of the American economy. This certainly was a credible theme in the late 1990s, but sudden and severe declines in the stock market since then have made that argument somewhat shaky. On the motivational side, two claims are made. First, by creating a “capitalist working class,” stock ownership increases the identification of workers with the free-enterprise system. Second, and of particular relevance to this book, is the argument that ownership of an employer’s stock increases employees’ identification with their companies and their motivation to perform.

What is the research evidence concerning the impact of stock ownership on employee attitudes, behavior, and company performance? Overall, the findings are modestly positive, the largest impact tending to be on employees’ identification with the company. A smaller percentage of studies—but still most—show a positive effect on more specific employee attitudes, such as job satisfaction; on employee behavior, such as absenteeism; and on company performance, such as overall labor productivity. Regarding labor productivity, the average productivity improvement that appears to result from employee stock ownership is on the order of 2–6 percent. To our knowledge, there has been no instance (at least none published) where the effect on performance has been demonstrably negative. (The studies in which the results were not positive simply showed no significant impact one way or the other.)

Why is the impact on firm performance not greater, especially because stock ownership seems to increase employees’ overall identification with the company? Part of the answer lies in the indirect relationship between how employees perform on the job and how their company’s stock performs. Numerous market forces affect stock price—forces well beyond employees’ control (and even a company’s control). Even if there weren’t such broad market forces, there are few individual employees (or groups of employees) in most corporations whose performance can realistically be said to have an impact on stock price. Workers can feel proud of their company’s stock performance and feel good about the financial benefits to them—those are important—but what is almost entirely missing is the personal sense and pride of direct impact and achievement. Recall that one of our criteria for the selection of a variable pay plan is that it should allow employees to see the impact of their performance. Theorists in the field refer to this as “line of sight,” and, of all the variable group pay plans, stock ownership is the weakest on this criterion.

Employee identification with the company in relation to stock ownership needs some elaboration. Although we lack systematic research on this, anecdotal and indirect evidence point to the company culture—especially employee participation in decision making—as affecting the impact of stock ownership on performance. Think about it: suppose a company with a broad-based stock ownership plan has a top-down management style (a “do as you’re told” style). The problems of line of sight are then compounded because employees have no mechanism—other than sheer physical effort—to influence even their own performance, much less the firm’s overall performance. For most employees, ownership is both a psychological and a financial matter. To obtain the full power of ownership, owning shares and “owning” psychologically the product of one’s job (because of involvement in decisions about it) should reinforce, not negate, each other. The strength of gainsharing, which is discussed later in this chapter, comes in significant measure from this reinforcement.

With regard to financial and psychological ownership, consider the condition opposite to what we have just described—namely, employees having much decision-making involvement but no financial return that is a direct result of that involvement. The theory behind many participative approaches (such as “quality circles”) seems to be that virtue—such as employee ideas that cut costs—is its own reward. Not quite. In the United States, the history of these techniques suggests that, when successful, employees at some point begin to question why they are not sharing directly in the financial gains. This is more than employees seeing an opportunity for additional income. At least equal in importance is their sense of equity: the desire not to feel manipulated and exploited. Also, the impact of money on an employee’s sense of achievement is lost when participation is not accompanied by financial return.

Another important issue regarding stock ownership is, of course, the impact on employees of a drop in stock value. Things are terrific when the stock appreciates, but a decline not only can be disappointing but can threaten to severely decimate an employee’s life’s savings. This can happen when the stock price drops simply due to economic or market conditions, but it can also be the result of unethical or blatantly illegal financial manipulations by corporate executives. The risks inherent in stock ownership therefore militate against this vehicle being selected as the primary—not to speak of the sole—means of variable compensation for a workforce.

Profit Sharing

About one-fifth of U.S. firms have some form of profit sharing, with the percentage among publicly held firms being close to two-fifths. The bulk of profit sharing is deferred, where the share is put into an employee retirement account. The plans are cash-only in one-fifth of the cases and, in one-tenth of the cases, employees can choose whether to defer or receive their share as cash. There is great variability in the profit-sharing formulas that are used—both in the amount distributed and in the threshold before distribution—and, in many companies, the formula is discretionary and can change each year.

As with employee stock ownership, profit sharing has its strong advocates. They argue that it is not only a way of sharing with employees the financial fruits of their labors but also a mechanism to increase employees’ understanding of the financial condition of their firms and their identification with their firms.

What does the research show about the effects of profit sharing on employee attitudes, behavior, and firm performance? Surprisingly, there is little research evidence concerning employee attitudes and behavior. About the most that can be said reliably on the basis of the research is that employees generally like the plans, which should come as no surprise. The exceptions, of course, are the times there is little or no profit to share, especially after years of significant profit sharing when it has become an expected part of one’s earnings or retirement savings.

Although research is lacking on the impact of profit sharing on attitudes such as identification with the firm, we would be surprised if they were much different from stock ownership. Profit sharing should promote a feeling that “we’re all in this together,” especially if there are not large discrepancies between the profit-sharing bonuses of top management and those of the rest of the workforce.

Quite a bit of work has been done on the effect of profit sharing on company performance. The findings are similar to employee stock ownership: the results range from positive to neutral, with the average improvement in labor productivity also in the 2–6 percent range. The proportion of studies with positive results is actually somewhat greater than is the case with stock ownership.

Profit sharing is similar to employee stock ownership in its relatively weak “line of sight” between employee performance and end-results. The flaw might be less severe than with stock ownership because profitability is not as affected by uncontrollable events as is stock price. Nevertheless, the contribution that most employees and employee groups can make to overall firm profitability is indistinct, so there is little impact on one’s personal sense of achievement. Some companies have sought to deal with this issue by instituting unit—such as divisional—profit-sharing plans. But, these units have also tended to be rather large entities, and it is doubtful that much improvement in line of sight was realized. In truly small organizations, such as small business units or independent businesses, the problem should be less severe.

In both stock ownership and profit sharing, the lack of timeliness of the reward magnifies the line-of-sight problem. It is well established that a reward has more impact if it is given close in time to the behavior being rewarded, since it better reinforces the desired behavior. This is a major problem in merit increase programs (where the employee’s performance is typically appraised and the salary increase given annually) and in stock ownership and profit-sharing plans.

As with employee stock ownership, there is some evidence that profit sharing has a greater impact when it’s part of a generally compatible culture, such as a high level of employee involvement in decisionmaking.

Gainsharing

Although it’s not as well known to the general public as are stock ownership and profit sharing, research shows that gainsharing has the largest positive impact on employee attitudes and performance. As the name says, it is a method for sharing gains with employees—the gains that employees themselves, as a group, achieve for the organization. Although a number of gainsharing plans exist—the most common being the Scanlon Plan, the Rucker Plan, and Improshare—they have the following characteristics in common:

• They are used in relatively small organizations (most successfully when the number of employees is less than 500).

• The performance is an operational measure, such as productivity or costs, rather than a financial measure such as profitability; only employee-controllable performance is used.

• The organization establishes a historical base period of performance for a group.

• Performance improvement over the base creates a bonus pool, which is the savings that the improvement has generated. Typically, about one-half of the pool is paid to employees, usually as a percentage of their base pay, with all participating employees receiving the same percentage. If there has been no gain, there is no pool; the bonuses are usually paid on a monthly or quarterly basis, the idea being that they should be paid as closely as possible to the performance that is being rewarded.

• Almost all gainsharing plans include heavy involvement by employees in developing and implementing ideas for improving performance.

Although gainsharing was employed until recently mostly in small manufacturing organizations, it has spread to service organizations, such as hotels, restaurants, insurance companies, hospitals, and banks. Estimates vary, but a good guess is that about 20 percent of American companies have gainsharing plans. In most cases, however, gainsharing is applied to just a minority of the workforce, such as those in a corporation’s manufacturing facility. The popularity of the approach appears to have increased over the last two to three decades.

A review of the research on gainsharing shows significant improvement in productivity in the large majority of organizations using the plan. The range of improvement, however, varies widely—it has been as low as 5 percent and as high as 78 percent, with the average at about 25 percent. The results, therefore, can be substantial. “The most important thing we know about gainsharing plans is that they work,” says Edward Lawler, probably the most prominent organization psychologist studying compensation systems and their effects.17

Here is an example of how a simple gainsharing plan might work:

• The average monthly sales in a base period, usually the previous year or 18 months, are calculated; say this is $1 million.

• The average monthly wage costs over the same base period are calculated; say this is $200,000.

• The ratio of wage costs to sales in the base period is therefore 20 percent.

• If sales in the first month of the gainsharing period is $1.2 million, the application of the ratio produces wage costs of $240,000.

• If the actual wage costs are $210,000, there is a $30,000 savings, which is to be split 50/50 between the employees and the company.

This is a “simple” gainsharing plan because it focuses on just one performance measure: the ratio of wage costs to sales. Other plans include a number of additional factors, such as quality and delivery performance, with each factor given a weight in the calculation of the “gain.”

The reasons gainsharing so often works well should be clear from our previous discussion. Of all the plans but individual piecework, gainsharing provides the clearest link between what employees do and the performance measure that determines the payment. Gainsharing has advantages in this respect even compared to individual piecework. In the latter, the “standard” developed by an engineer is often disputed and is likely to be increased if exceeded by the worker (through greater effort or a change in work method). Therefore, doing more (especially by being smarter) is usually the path to a heavier workload, not greater earnings. In gainsharing, the “standard” is the past—workers know it can be met because it has been met, and rewards are distributed based on improvement over it. The link is clear—do more to get more—and the system encourages, rather than discourages, improvement.

It is naïve to think that gainsharing, despite its obvious advantages, can be introduced simply as a formula mechanically relating productivity improvement to compensation. Its organizational context is critical: by far, the most successful applications are paralleled by a highly participative and team-enhancing process because the primary way gains are realized is by employees working collaboratively and innovatively to improve performance. We made this same point about “ownership” in our discussions of employee stock ownership and profit sharing, but it is even more obvious and important here. Gainsharing ties the bonuses of a group of employees to their ability to improve performance—the performance that they largely control—over the past year. Because gainsharing focuses on a specific group, it would be self-defeating and ludicrous for the organization not to encourage the group members to work together to generate and try out improvement ideas. The very structure of gainsharing calls for a process that achieves results greater than the sum of the efforts of individual employees. This is not nearly so much the case with employee stock ownership and profit sharing where, because of the broad compass of the measure (usually an entire company), the emphasis can still be on individuals’ performances.

Given its proven effectiveness, why is gainsharing not more widespread? Among the most important of the conditions that make gainsharing difficult to implement are the following:

• When it is difficult to measure quantitatively the output of the organization, such as that of a research laboratory.

• When performance measures fluctuate widely because of factors well beyond the employees’ control, and the employees’ impact can’t therefore be reliably assessed.

• When it is difficult to differentiate relatively autonomous, properly sized entities in an organization to which the plan can be applied.

• When little or no interdependence exists among the members of the group, or the group members are strongly disposed to working on an individual incentive basis.

• When the organization is not culturally ready for gainsharing, such as when management fundamentally does not believe in the value of employee participation, or when there is great distrust and conflict between management and workers.

A few words about trust: although gainsharing can reinforce and strengthen trust, it should not be expected to turn a hostile environment into one of sweetness and light. To be successful, gainsharing depends on mutual trust and confidence. Especially important, obviously, is that workers trust that higher performance leads to better pay. Even though a performance formula—such as the ratio of labor costs to sales—looks simple, it can be subject to considerable dispute and will almost certainly be disputed if fundamental trust is lacking. Therefore, when there is a history of conflict and distrust, it is important to make significant progress on those issues before introducing a gainsharing plan.

Employees must also feel they won’t be punished for higher performance. How can a reward program be punishing? Ask workers what “higher productivity” means to them, and you often discover that it means “fewer workers needed.” Another term for “rate buster,” in fact, is “job killer.” Workers won’t voluntarily participate in the arrangements for their own funerals, so guarantees need to be given to them that any gains from gainsharing won’t result in job losses for them. The most successful gainsharing programs do that.

Even when all the conditions we have described have been met, gainsharing still has two major gaps. For one, because it lacks a total corporation focus, it does little to enhance organization-wide identification or increase employees’ understanding of the broad financial condition of a business. Lawler suggests that “the ideal combination for many large corporations would seem to be corporate-wide profit sharing and stock ownership plans, with gainsharing plans in major operating plants or units.”18 In other words, the three types of variable group pay plans we have discussed should be viewed as having somewhat different objectives and are often best used in combination.

The second gap is the lack of individual financial reward. We believe that in most situations—covering the great majority of workers—this should be handled not by differentiating bonuses by individual performance, but by giving special awards to group members who make a particularly outstanding contribution. Although these awards should have a monetary value, their basic function is to honor individuals. We discuss such outstanding contribution awards in Chapter 10, “Feedback, Recognition, and Reward.” Suffice it to say for now that these awards should be truly special—given infrequently, given publicly, and signifying appreciation from both management and peers.

A Note on Merit Pay for Teachers

Among the most contentious issues in education today—and receiving great publicity since the publication of our first edition—is the compensation system for teachers. By and large, teachers get paid by their level of education and the number of years they’ve worked. The worrisome state of academic achievement of students in the United States has resulted in numerous proposals for improvement, with the quality of teaching receiving outsized attention. Taking a page from the private sector, critics have homed in on teacher pay. The basic proposal is that the pay system be changed so that, emulating what is assumed to be the case in the private sector, high-performing individual teachers are rewarded with larger salary increases or other kinds of financial rewards.

We know of no reason to believe that merit pay will work any better for teachers than it has in companies. Indeed, over the past two decades or so, experimental merit pay plans for teachers have been introduced and studied, and the evidence for their effectiveness is, to say the least, not impressive. One scholar reviewing the research on merit pay concludes that, although these plans were expected to increase accountability among teachers and performance in the classroom, they “not only failed to improve student achievement, but also destroyed teachers’ collaboration with each other and teachers’ trust in the administrators...evaluating their performance.”19

The National Center on Performance Incentives at Vanderbilt University published in 2010 a description of its research on merit pay for teachers in the Nashville public schools. Teachers were offered bonuses of up to $15,000 a year for improved student test scores on standardized tests. Their conclusion: merit pay “did not do much of anything.” Teachers on the merit pay system showed no greater gains than teachers who were not offered merit pay.20 Allan Odden concluded from his review of the experience and research in the field that “merit pay is at odds with the team-based, collegial character of well-functioning schools, and thus have limited potential to support school improvement.”21