9. Job Challenge

“The greatest analgesic, soporific, stimulant, tranquilizer, narcotic, and to some extent even antibiotic—in short, the closest thing to a genuine panacea—known to medical science is work.”

—Thomas Szasz, M.D., psychiatrist, author

The previous chapter focused on enablement, covering the type of organization that allows workers to get their jobs done and the positive impact that such enablement has on their satisfaction and pride. But efficient, even high-quality performance is not sufficient. The work itself—what is done—is also critical.

For example, for many workers, doing simple, repetitive work for long periods of time (no matter how well done) can be highly unsatisfying, even intolerable. Here are some comments from employees in these jobs about the work itself (in response to the question about what they like least in the company):

(I dislike) waking up in the morning to come to this boring job...my skills are being wasted daily!

Dealing with the repetitiveness. My job is always the same in my case. I don’t have much of a variety of things to do, so sometimes things can be mind-numbing, frustrating, or even stressful.

The type of work we do is very tedious, and it is very hard not to get in a rut. Sometimes, the pressure of the job can get to you. You can feel the anxiety building up as soon as you enter the building.

This job is monotonous. After say, three months, there is no longer any challenge. Just being able to sit at a desk for hours at a time is the most challenge I face.

My job is mundane. It can be very boring, so it is a challenge to enjoy the actual work I do, even though I enjoy the company as a whole.

My job does not require much grey matter. I think my 12-year-old sister could do it.

Those comments are from people for whom challenging work is important and whose jobs don’t provide it. The literature on work, as we have said, contains a great deal of social commentary on the presumed debilitating and dehumanizing nature of routine jobs. We are all familiar with the depiction of much work as so boring that only a trained monkey could bear it.

We would expect, therefore, a large percentage of people to be unhappy with their work. Even more broadly, it is widely believed that people are inherently averse to work anyway, no matter how it is structured. According to this view, job satisfaction is a contradiction in terms; we work because we are forced to, not because we want to. While it is a widely held, in fact ancient, notion, it is a misconception.

As reported earlier, 78 percent of millions of surveyed workers say they like their jobs. Only 7 percent report dissatisfaction. Furthermore, the range of responses from the least positive to the most positive organization on this point is from 50 percent to 92 percent. Therefore, even in the organization with employees least happy with their jobs, half are still favorable. These results, as we have pointed out, show surprisingly little variation by the type of work people do. For example, whereas 83 percent of salaried employees express satisfaction with their jobs, 78 percent of hourly employees do so.1

Is This an Aberration, Are Workers Delusional, or Are They Lying?

None of the above. You can gain insight into how some people view the work itself from this not atypical interchange, which is abstracted from a focus group of packers in a cookie and cracker factory. These women do routine and repetitive work.

FOCUS GROUP MODERATOR: What is it that you particularly like about working here?

WORKER 1: We get good pay and this company has been here forever so I feel secure here.

WORKER 2: Our pay has kept up with the cost of living—that’s really important to me.

WORKER 3: I like the fact that we are making a product that people really enjoy. It makes me feel good to know that what I do makes people happy.

WORKER 4: We can have as much product as we like for free at lunch and coffee breaks but we shouldn’t be eating so much. [Laughter] But the cookies really are so good.

MODERATOR: Now, what do you particularly dislike about working here?

WORKER 1: The equipment. It keeps breaking down. They only have two maintenance people left. It’s crazy! We lose so much production waiting for maintenance to show up.

WORKER 4: My forelady—she is always looking over my shoulder, trying to make sure I’m working and doing my work right. I’ve been here 27 years, for goodness sake, doing the same thing, and she wants to make sure I know how to do it?

WORKER 3: I don’t think that management thinks we’re very smart. They almost never ask for our opinions and we could help. There’s a lot of wastage now.

MODERATOR: For example?

WORKER 3: For example, we see when a machine is running so fast that it’s sure to break down. And it always does. I’ve stopped telling them because they don’t listen.

(Additional dislikes were then mentioned, such as sometimes being asked to work overtime on too short notice, heating and air conditioning that don’t work well (“it’s either too hot or too cold”), a co-worker who “gets away with murder,” and the factory general manager who “just looks straight ahead and never says hello.”)

MODERATOR: Nobody mentioned the actual work you do, packing cookies and crackers. Do you like this kind of work?

WORKER 1: It’s fine; it’s a job. I’m happy to have it and I do it well.

WORKER 2: Well, really, the work is boring; I’m doing the same thing over and over again. I’d rather be doing something else. Sometimes, I feel like I just can’t do it anymore. I feel like a machine, but I’m too old to change jobs now.

WORKER 3: It’s not very interesting, it’s the same thing every day, but to tell you the truth, I don’t much care. Because we don’t have to think on the job, we can talk to each other. We really socialize; I love that, with all the ladies.

WORKER 4: Look, I’m lucky to have a steady job. My father was always getting laid off, always worried.

WORKER 5: Frankly, although I wouldn’t say I hate the work, it does get boring. I’d like to do something more interesting. I want to do bookkeeping and I’m thinking of going to night school for it.

WORKER 6: This job is good enough for me. I couldn’t be a bookkeeper, numbers make my head spin.

WORKER 7: As (name) said, it’s a job and a pretty good one when you consider that I don’t have much education.

MODERATOR: Would any of you be interested in a promotion to a management position, such as forelady?

WORKER 2: Not interested—who needs all those headaches? When I leave work, I don’t want to think about it.

WORKER 7: And we’d lose our union membership and overtime pay. It’s more work for very little more pay.

WORKER 6: I couldn’t stand managing people. They’re a headache. And I’d lose my friends because of the things I’d have to do, like discipline them. I’d be terrible at that.

WORKER 5: Me, I think I could do it. I would certainly like to try if they would give me training. I’m a good organizer. But I’ve never been asked.

Notice the two different reactions to the routine nature of the work: Worker 2 said she felt like a machine sometimes, but most of the others had different reactions. Although the latter workers were not particularly positive (“it’s a job”), they were certainly not particularly negative. Judging from their other comments (about equipment, the forelady, and so on), these women were not reluctant to express the negative views they did have. Their opinions about their jobs stand in contrast to the earlier ones cited, selected from employees in a number of different companies who expressed great unhappiness with the routine nature of their work.

The divergence in views supports what is obvious to us all: people differ enormously in what is attractive or unattractive to them about the content of jobs. Although there are also individual differences in the other needs we have discussed in this book, such as the importance of job security or camaraderie, these differences are small compared to the great variations in the kinds of jobs people prefer.

The variations are of two kinds. One concerns sheer preference for a type of work based on interest or personality or upbringing. Some people, for example, prefer outdoor to indoor work, office work to factory work, working near one’s boss to being “on one’s own” (such as a salesperson), working in the private or the public or the not-for-profit sectors, 9-to-5 jobs versus jobs with often long and uncertain working hours, and predictable to unpredictable job routines.

Given a Choice, Few People Volunteer to Fail

A second set of differences comes from people’s sense of what they can do well. Being a professional athlete is awfully appealing to many youngsters, but they learn quickly whether they have the rare talent to be successful at it. Few without that talent continue trying for long.

As we know, workers want to be proud of what they do. If the job involves managing others, for example, and an employee doesn’t feel she is good at that, she keeps away from management positions. If someone is poor in math, he keeps away from engineering studies and engineering jobs. If he is clumsy, he doesn’t seek jobs requiring a lot of manual dexterity.

This is why we don’t see more dissatisfaction with the work itself in our surveys, even among those who do repetitive and routine work. Many of us could not do repetitive work for long without feeling great frustration. But although we choose not to do repetitive work, others do choose to do it. They are not, by and large, unhappy with their choice.

Some workers feel that they’re good primarily at doing the same thing over and over. In addition to the cookie and cracker factory workers, consider Melvin Reich, who’s known as the buttonhole man:

Would you want to make buttonholes day in and day out? The New York Times recently ran an offbeat article on Melvin Reich, Manhattan’s premier buttonhole man. “Buttonholes are what we do. We do buttonholes and buttonholes and buttonholes. I am specialized, like the doctors,” said Reich. “You think it’s nothing. Just a buttonhole. But it’s something. It’s not nothing.” And the clincher: “Zippers are a totally different field. It’s a different game. A man can do so much.”2

Note that in the group of cookie packers, only one worker expressed interest in a management position. Many workers share the view of “Who needs the headaches?” Other workers, however, thrive on those headaches. So, you might sensibly ask, “Who is the more rational (or less neurotic): workers who just want to do their jobs with minimum problems and stress and leave work without thinking any more about it, or people who appear to be unable to live without work-related stress 24/7?

We are being facetious to make the point that understanding workers requires that we put ourselves in their shoes, asking what they want from a job. What some workers avoid as “stressful,” others seek out as “challenging.” Putting ourselves in other people’s shoes requires suspending evaluative judgments—such as judging to be demeaning the kinds of work that millions of people choose to do—and asserting that they must (or should) be unhappy with it.

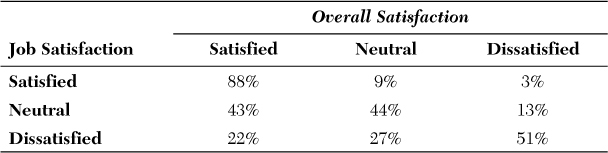

Although a free labor market allows for the diversity of individual preferences to be matched by the diversity of jobs, it doesn’t always work that way. In our surveys, an average of 7 percent say that they are dissatisfied with their jobs; so, some people obviously do find themselves doing a job they dislike. This group is a small fraction of the workforce, but the consequence of that unhappiness for their overall morale is huge. For example, 51 percent of employees who are dissatisfied with the work itself express dissatisfaction with the company overall, while only 3 percent of those satisfied with their jobs express such dissatisfaction. Table 9-1 shows the relationship between satisfaction with the work itself and overall satisfaction with an organization.

Given the importance of the work itself and the diversity of jobs available, why do some people wind up in jobs they dislike?

For one, mistakes can be made in job choices, especially in initial choices. For example, people might misjudge their abilities or be wrong about the abilities a job requires so, early in their employment, they search for other, more compatible opportunities. That is a major reason so much voluntary or mutually-agreed-upon turnover occurs within the first year or so of employment. That is healthy turnover because people should not stay in jobs they dislike, and organizations should not want them to stay.

Sometimes, however, people get “stuck” in a job that it is difficult or impossible to leave, often for financial reasons. The need to earn a living can lead people to take and keep jobs that they dislike, sometimes intensely. That is truly a sad situation—spending eight hours a day being miserable. It’s most pronounced in times of economic downturn when work is scarce, and in a person’s middle and later career stages when leaving an organization to search for another job can result in significant financial loss. The latter is the familiar case of the “golden handcuffs”: pensions, stock options, and the like hold employees in jobs with which they are unhappy and in which they might remain for a long time just for financial reasons. Yes, man does not live by bread alone, but bread is important, especially with mortgages, college tuitions to pay, and, later in life, the need to retire with financial security.

Push and Pull

It’s helpful to view job choice, retention, and satisfaction as the result of motivational push-pull forces. Pull forces are the factors that make a job choice (or any choice) attractive, like the interest a person has in the job, its challenge, and the promise of excitement.

On the other hand, push forces feel like coercive influences, in the sense of driving or forcing us against our will toward the choice. It might be the need to please other people (“I promised my parents I would be a doctor!”), a choice between the lesser of two evils, or, perhaps, the need just to make a living (“I have to eat.”).

When the pull forces predominate, you arise each morning and look forward to going to work. When only push forces exist, your action of choice when the sun rises is hitting the snooze button. Let’s now complicate it a bit. Sometimes the type of work is desirable, but it has been structured by the organization, or managed by a manager, in a way that makes it onerous for the job occupant. Although only 7 percent express dissatisfaction with “the job itself—the kind of work you do,” the results are considerably less positive on other questions regarding the job. For example, we saw how bureaucracy can affect employee attitudes. In other words, the kind of work might be desirable, but not the context in which it is performed. Consider these views, abstracted from an interview with Terry, a sales representative in a telecommunications company:

Terry loves sales work but finds his sales job in the company to be a miserable experience.

Terry loves the challenge of selling. He is most happy when he is with customers, either pursuing or servicing accounts. He is a salesman’s salesman. He derives great pleasure from landing accounts and doing the things necessary to keep customers loyal. The money is important to him as it is to other salespeople, but Terry absolutely loves the activity itself. He believes in his product and in himself. He genuinely likes people, and people seem to like Terry. He is highly motivated to deliver on each promise to his clients, and he does not sleep well if he misses any.

Give him a territory, a challenging quota, a clear, accurate compensation plan, and a smart leader who points him in the right direction, and he is a happy employee who will deliver the goods. What else would someone want from a salesman?

Unfortunately for Terry and the company, Terry’s day is significantly consumed by something other than selling. Paperwork is the bane of a salesperson’s existence. Some of this administrative activity is seen as an unavoidable and necessary evil by salespeople and is absolutely required to keep track of important outcomes.

But, unfortunately, Terry reports to Mr. Pitz, a former top salesman, who also fashions himself an innovative administrator. Mr. Pitz established an elaborate database that tracks every interaction each salesperson has with each customer contact. He calls it TCTS (Total Customer Tracking System). The level of detail of his database grows every month and, thus, its attendant burden on his salespeople. In fact, part of the performance evaluation of his people is the thoroughness of their data input. Mr. Pitz presented his system to top management, and they were impressed. The impact of the system on Terry echoes our comments in the previous chapter about bureaucracy.

Terry and his colleagues must track each contact they have with customers and record the nature of the customer’s business (its gross revenue, number of employees, geography, and ten other demographic characteristics); details of the conversation (whom they talked to, what their job title is, whether they bought and, if so, how much, what the tone of the conversation was); and the reasons of those who didn’t buy (budget issues, satisfaction with current supplier, reputation of Terry’s company).

Despite the fact that some of this information could be useful, Terry feels that he has been relegated to doing the job of a clerk rather than a salesman for a significant part of his day. It interferes with his ability to sell. Terry would like to leave the company, but he feels he can’t because of his pay and pension, which he believes he cannot duplicate elsewhere.

Terry loves the work itself—sales—but not his sales job in C&A. Of course, some people just won’t put up with a job in which they’re miserable, no matter what the financial impact of leaving; witness the following write-in comment from a survey:

People are leaving this company for the competition and cannot believe the difference in stress level and how much better they are treated at their new job. We are constantly being pulled into internal conference calls, district calls, training, etc. Sixty percent of my time is spent on internal non-value work. Valuable people will continue to leave the organization unless some of the non-value internal initiatives are eliminated. This company is burning people out! I’m going to leave even if I can’t immediately find a job elsewhere. I’ll just take a little time off to recover and look for something else

When employees are unhappy in their current situation, it’s fortunate when they also feel able to leave it. However, many employees are like Terry; for whatever reason (financial, lack of self-confidence), they feel stuck. Terry very much wants to be a salesman—it’s his dream career—but it has become a nightmare. We will continue this discussion of job structure and what organizations should do about it later in this chapter. But first we need to return to the near-universal desire of people to feel proud of their work.

Although there are large differences in the kinds of work and occupations people prefer, almost everyone wants to be proud of what he does. Pride in the job comes from three sources: performing well, using valued skills, and doing something of significance.

Performing Well

The criteria workers use to judge their performance have both external sources (such as what the company or immediate boss wants) and internal sources (how the worker himself judges his performance, which, in turn, almost always has past external sources, especially the standards emphasized in training). The two most common criteria for evaluating job performance are quantity and quality of work, but it is quality that is the more important source of worker pride. Turning out a lot of work is just not as meaningful in terms of self-esteem as doing something well.3 This underlies a good deal of the frequent conflict between workers and management about the amount of work expected. It is not just workers’ resistance to a pace that will leave them physically exhausted or even harm their health. Those are, of course, important, but workers also fear the impact of undue production pressure on their ability to produce quality work and provide quality service to customers. That issue, in other words, is a matter of their pride. The following comments illustrate this point (in response to the question of what you like least about working here):

The ongoing facade that quality is so important, when in actuality, very little value is placed upon it; with the vast majority of emphasis placed on the all-important numbers, the quantity, the production, etc. My over 100 percent quality means absolutely nothing in comparison with my low numbers. Poor quality is OK, low numbers are not! But poor quality is not OK with me!

The incredible fast pace that everyone works at this company is a problem. I can’t help but wonder if people at other companies work at such an incredibly fast pace. Things cannot keep speeding faster and faster, which seems to be the plan. We can’t do the high-quality work we are capable of because there is not enough time to read, think, and make smart decisions and plans.

There are so many customer complaints due to layoffs and outsourcing of systems, which result in poor quality and slow response times. Supposedly it saves money, but down times are increased and clients and customers are given poorer service. I hate hearing customer complaints but there’s nothing we can do. No matter what we say, we are budget driven rather than quality driven.

It is easy to interpret resistance to production pressure as proof of workers’ laziness. But few workers want a lax, laissez-faire environment—there is no pride in that. They object to an emphasis on quantity when it becomes excessive and detrimental to their physical well-being, the quality of their work, and the organization’s reputation with its customers.

Using Valued Skills

Self-esteem flows not just from performing well, but doing so in a way that uses skills that the employee values. In a broad sense, the importance of quality derives from this because quality is associated with traits that workers value—traits that are distinctly human, such as craftsmanship, dedication, and judgment. Sheer production, on the other hand, is most closely associated with the nonhuman world, such as robots and the proverbial “trained monkeys.” In fact, for speed of output, it is rare that any human can beat a machine.

Within the human world—the world of workers—there are numerous kinds and levels of valued skill, and it is a source of great frustration when these skills are not used:

This organization must work on utilizing the abilities and brains of the administrative staff. It’s very difficult doing exactly the same tasks over and over every month. Just because you are very good at something does not mean it’s all you are capable of!

My management does not have sufficient tech skills to manage me in a technical environment. They do not use my skills properly. I work more as a technician than an engineer. It’s galling not to be treated as a professional.

The bureaucracy is stifling. I have a management title and believe I have strong management abilities, but I’m not allowed to function as a manager. I am micro-managed every step of the way. My manager constantly goes around me directly to my employees. When he goes through me, I’m just a messenger for him.

I was hired here to run Sales. The CEO was head of Sales at one time and still acts that way. I get almost no latitude. I was told when I was hired that he wanted new ideas because things were stagnant. That was just talk. I’m really his A. A. [administrative assistant]. He’s not going to change and it’s time to get out of here.

I feel like a trained monkey on this job. It’s so routine and predetermined that there is absolutely no room for using my judgment, my education. It’s really debilitating.

My greatest challenge is surviving the day. I feel there is way too much emphasis on administrative activities, rather than satisfying customer needs. My customer service skills are atrophying.

On the other hand, when workers feel that their skills are being fully used, it becomes a source of joy:

I like the autonomy given me by my leader to use my professional skills and experience to accomplish my daily tasks. I am especially pleased about my leaders’ confidence in me as a person and in my abilities. This empowers me with the motivation and pride to perform my job at this company with 100 percent dedication to my client and my employer.

I am really using and further developing my skills—I just love it! Who would have believed that I would have fallen into a job like this at my age—they trust me with major assignments such as managing relationships with pretty big customers.

It’s very pleasurable not having a pigeon-holed job. Instead, things here are dynamic and new skills are learned every day.

I feel blessed to have the opportunity to succeed, learn, grow, and enhance my current management, HR, conflict resolution, and sales skills.

When a worker has a skill that is both important and unique or unusual in his workplace, it is a source of great joy. Being considered the expert in your field of work is a terrific feeling:

I hate to boast, but I don’t know what they’d do here without me.

My leadership and technological skills have increased immeasurably over the last five-plus years. I am extremely grateful to the company. It is a source of great pride to me to be regularly sought out and asked by other managers what to do in particular situations.

Many workers are interested in gaining additional valued skills through training. Training, of course, has many positive consequences for a worker in addition to a heightened sense of competence and pride, such as higher potential income within and outside the organization and greater job security. The importance of training, especially in fields that rapidly change, has been demonstrated in many studies. For example, in a survey of the goals of technical employees in 25 countries, we found that receiving training—continual training—ranked at or near the top in every country in what employees say they want from their jobs.4

Doing Work of Significance

In addition to performing well and having their skills used, employees want to feel that what they do makes a difference, especially to their organizations and to the organization’s customers. Professional employees are also often interested in having an impact on the status and progress of their professions.

We are not referring to Nobel Prize–type contributions. The workers at the cookie factory were pleased that the product they packed “made people happy.” The following comments help illustrate the point:

I like the fact that you are recognized for your contributions, and rewarded for them. I have had a really good year and made the company a lot of money. I’m proud and lucky enough to be able to go on the [destination] trip for Outstanding Contributors.

My boss told me that I am essential to this department. That’s the kind of boss he is. Compliments like that keep me going.

The best part of my job when all is said and done is providing good service to the customers. Pleasant and satisfied customers make the work seem like fun.

It is important to me that I feel I am contributing to my customers’ success. It is especially gratifying when a customer lets me know that I have helped him or her. I feel that’s why I’m here!

In this company, they don’t make you feel small. They make every employee feel important, that he or she is a key part of the company’s success. That works like magic for our morale.

Employees’ interest in doing high-quality work comes, in part, from their concern for customers. Customer satisfaction is mentioned frequently in employee focus groups: on the positive side when workers feel that they have served customers well, and with frustration and disappointment when they feel they have not, usually because, as they see it, their ability to provide quality service was severely hampered by workload or other obstacles.

Making a difference to customers again brings us to the matter of workers doing the “whole thing” rather than each worker being responsible for a fragment of a product or service. Although it’s usually discussed in terms of products, such as producing an entire automobile engine, let’s apply it here to servicing customers. Our first example is a bit far-out: the “customers” are laboratory animals.

One of this book’s authors was engaged by the chief veterinarian of a pharmaceuticals company to help him understand and do something about the morale of the laboratory-animal caretakers. The veterinarian said that the caretakers were lethargic about their work, such as not cleaning the cages well, feeding the animals late, and coming to work late. In his words, “They are a really unenthusiastic crowd.” His continual exhortations to them to improve did little good: things changed for a few days and then returned to their previous mediocre level.

On the basis of in-depth interviews with each of the caretakers, we concluded that the key issue for them was their highly fragmented work. They were happy with the basics of their employment (pay, benefits, and job security) and liked their supervisor, but they found their jobs dull and almost without meaning. But they also said that they enjoyed animals and saw the work done in the laboratory as important. How, then, could their work be dull and meaningless?

The heart of the problem was that each caretaker was responsible for just one function: filling the food and water dishes, or cleaning the cages, or administering medications, or keeping daily records (of food intake, weight, and so on). The work became routine: cleaning out the cages in the same way every day with little or no use of higher-order skills and little or no sense of responsibility for, or impact on, the “customer”—the whole customer. As one caretaker put it, “My job is not to take care of the animal; it’s to shovel s....”

Unlike the cookie packers, the animal caretakers greatly disliked their fragmented jobs. The solution was obvious and was put into effect: each caretaker was given his own group of animals and almost all of the responsibility for their care. This required some training of the caretakers in their various functions, including instruction in rudimentary diagnostic techniques to help them know their animals and their condition. The training and brief learning curves on the job were about the only costs incurred in making the transition to the enriched jobs.

Follow-up interviews uncovered significantly improved job satisfaction, including the feeling that their caretaker work was now, as they put it, “more professional.” The veterinarian reported that, with the exception of one caretaker who continued to be a problem and was eventually dismissed, the performance problems had pretty much evaporated.

Almost by definition, a sense of accomplishment means completing something, doing a job from beginning to end so that a worker can see the fruits of her labors. But, as previously pointed out, this is not always easy to accomplish because doing the “whole job,” on an automobile assembly line, for example, can result in severe efficiency losses.

As a general principle, every effort should be made, within the constraints of maintaining efficiency, to design work so that workers have a sense of completeness to their tasks. A second principle is that it is almost invariably desirable—and especially when efficiency issues severely limit providing complete tasks for individuals—to organize by self-managing teams (SMTs) that do have beginning-to-end responsibility for significant operations. As noted in the previous chapter, SMTs are delegated responsibility for tasks such as scheduling, assigning work, improving methods, taking care of maintenance, training on the job, and performing quality control. These are a complete and enriched set of responsibilities in which individual workers participate and from which, as a team, they obtain a sense of achievement and pride.

To the extent possible, the team should also be responsible and accountable for relationships with customers. This is important because it is primarily through the customer relationship that people learn whether their work has, indeed, made a difference. Although many employees do not have contact with external customers, everyone in an organization can be said to have a customer—if not external, then internal. In a manufacturing plant, for example, those who machine parts have those who assemble them as customers. Among the customers of product development are manufacturing and sales. The customers of staff groups, such as Human Resources and Information Technology, are the line divisions.

Chapter 11, “Teamwork,” details the relationships between an organization’s units, and between them and the external customers. Suffice it to say for now that effectiveness and job satisfaction are greatly enhanced by organizing the teams around identified customers and setting the primary goal of the teams as meeting the needs of their customers in an efficient manner.

Organizing around the customer allows employees to focus on customers and their needs, and, if communications channels are structured properly, it permits them to know the extent to which those needs are being met. We have said that making a difference—to customers, their company, perhaps to their profession—is important for employees’ job satisfaction. What we have largely omitted from the discussion thus far is how employees know that they have made a difference. They might feel that they know based on self-evaluation, but that is usually inadequate. Clear and regular feedback is absolutely vital from those the work is meant to affect. Such feedback provides both the information workers need for evaluating and improving their performance and the recognition for good performance that is so crucial for maintaining a high level of worker motivation and morale. In the following chapter, we discuss feedback, recognition, and reward.