8. Job Enablement

“Most of what we call management consists of making it difficult for people to get their work done.”

—Peter F. Drucker

We discussed in the previous chapter the purpose of work (doing something that matters), and in this chapter we focus on the business practices that enable workers to actually perform on their jobs and do so at a high level.

At the end of a day’s work, workers want to feel that something was accomplished by virtue of their efforts. A factory employee becomes disheartened when he produces little during the day because of time spent struggling with faulty equipment and waiting for the maintenance person to arrive. An executive feels equally frustrated when she spends her day in endless departmental meetings with little discernible accomplishment. Those wasted days are depressing for most workers at all levels.

A large body of research supports these common-sense observations, but, as always, the qualitative data are compelling. There are many complaints about obstacles expressed in the write-in comments and, in our examples that follow, we highlight the various types of obstacles to make it easier to get through them. Here is a sampling of comments about what employees like least about their jobs and what can be done to improve effectiveness:

Our operations are needlessly complex which result in too many customer service and client-satisfaction issues.

I hate the bureaucracy—we need approvals for just about everything and the number of sign-offs is ridiculous.

I am constantly challenged by teams and individuals that resist change and have silo mentalities. Cost control and management for technology spending is not well controlled or understood. This restricts my business’ ability to effectively understand costs and reengineer.

We must put an end to obsolete practices, with people who are afraid of change and who are an obstacle for the company. There’s also the lack of communication about processes and policies within the company, which results in redone work and failure.

We don’t talk much to each other across department lines and so there’s a lot of duplication of effort and continual “reinventing the wheel.” It is extraordinarily wasteful.

We spend too much time chasing numbers. We are not looking at the product; we just make sure it moves fast. It can be dirty and ugly but let’s make sure it moves.

A lot of time is spent satisfying some ambiguous policies that everybody has a different interpretation of.

Simplification of the work processes so employees can get their work done without unnecessary delays.

We need to slow down with all the major changes we make, as an agency. We have been inundated in the field and have to endure so many changes both systematically and programmatically, it has been entirely too much to absorb. The staff believes quality must come first but they also cannot afford to spend hours searching for an answer to a question.

The largest obstacle here is too much work...which hurts quality and creates a tremendous amount of stress due to...lack of balance between work and family life.

One obstacle is the lack of cooperation with other departments in the organization. Everyone has an emphasis on satisfying “their” customer, which means that if you need their cooperation in serving your customer, your customer is not their customer so you are a low priority.

The red tape is an obstacle I face in getting my job done.

One obstacle is company politics.

There has been little or no communication from our management staff as to the direction, roles, and responsibilities that we will have.

We have been fire-fighting instead of...planning.

The lack of training to extend my areas of expertise is one obstacle I face in getting my job done.

There are constant organizational restructuring changes... I’m not even sure who my supervisor is at this point.

Preventative maintenance is a myth here.

Maybe I would feel better about all the reports we’re required to fill out if I knew what they were for! They fall into a big pit never to be seen again.

However, when things go well, when workers genuinely feel accomplishment, their spirits are buoyed. Again, we highlight the key sense of the employees’ comments:

The huge advantage this company enjoys in its industry is that employees like me are empowered to make decisions and there is very little to no red tape, unnecessary delays, no wasted time, no wasteful projects, and no unnecessary reporting. Management, keep up the good work.

The group I work with is led by a manager with a unique leadership style. She allows individuals...to fully utilize their creativity, business knowledge, and talents, in a teamwork environment to meet the challenges of our business. With each project, there is always a great sense of pride and accomplishment. My leader is not the one in the spotlight, she is the one leading the applause. Thanks to her for making the company the best place to work.

My immediate leaders both allow me to perform my daily duties at a high level. They have confidence and trust in the decisions I make. This trust and their being available allow for self-confidence and performance levels to be above expectations. I want to thank them for listening to and resolving our concerns when presented.

I have the freedom to go above and beyond for the customer and to put them first. That gives me a feeling of accomplishment.

I enjoy the flexibility offered by working from a virtual office. I like to create my own schedule in order to accomplish what I need to on a day-to-day basis.

The opportunity to act independently of my team when accomplishing the necessary work of my job, while at the same time knowing whenever I need my team’s assistance, they’re always right there.

I feel one of the main strengths of this company is its willingness to work with their customers on a one-to-one basis. This makes the customer feel more confident in the place they chose to do business and makes my job that much enjoyable.

You know what you have to do and (you have) the tools to accomplish the task with teamwork encouraged. We have the most up-to-date equipment.

The empowerment levels have risen in my department, and for that, I say thank you. Nothing is more encouraging than being able to say to a customer, “I can do that right now for you,” or, “I can get it done by tomorrow no problem,” and mean it.

We have the tools and ability to really produce dynamic, cutting-edge solutions. I love working for an organization...that accomplishes many great results and has great care and compassion for people.

The survey data discussed in Chapter 1, “What Workers Want—The Big Picture,” which portrayed, among other attitudes, how workers feel about their ability to get their jobs done, showed variability in two ways. First, organizations differ greatly from each other. Although, on average, 67 percent of employees rate their organizations favorably on the overall effectiveness with which they are managed, the range is enormous: 32 to 93 percent. Obviously, some organizations are seen as highly effective and in others, from the employees’ perspectives, it is a wonder that anything ever gets done! Workers dislike the latter intensely because they have little or no sense of accomplishment—indeed, working there embarrasses them—and because an ineffectively managed organization does not bode well for long-term job security or advancement prospects. A high degree of perceived effectiveness is a condition for worker enthusiasm.

In addition to the differences between organizations, there is great variability in the kinds of obstacles employees report encountering while doing their jobs. Over the many companies we have surveyed, one of the highest average percent favorable scores (86 percent) is obtained in response to the question, “I have a clear idea of the results expected of me on my job.” One of the least favorable results (39 percent) is in response to a question about bureaucracy interfering with their jobs.

Therefore, although it is a favorite topic in the management literature, the pervasive problem for employees is not lack of information about what to do. They know what they have to do. Instead, it is getting the tasks done in the face of the barriers organizations erect, however unintentionally, to their accomplishment. The latter illustrates the law of unintended consequences: bureaucratic procedures introduced with the best of intentions can make it excruciatingly difficult for any task to be accomplished or decision to be made.

Where in organizations do we find the most pervasive obstacles? We established previously that employees tend to be most positive toward the two opposite poles of an organization: the immediate work environment and the total organization. Examples of the former are the clarity of the results expected from the worker, the immediate supervisor’s technical competence, the skills and abilities of co-workers, and the job itself. The total organization level includes views of the company’s profitability and the quality of the products or services the organization produces for its customers.

Although some organizations are viewed as dysfunctional from top to bottom, the tendency is for the major problems, as seen by employees, to be in the “middle”: below senior management and the organization as a whole and above the immediate manager and immediate work environment. It is as if the products produced and the profits achieved come despite what goes on at those levels. Consider this comment:

It is amazing that the (product) we deliver to the (government agency) is of such high quality considering the lousy tools we have, the politics in management, people finger-pointing and screaming at each other, and the unbelievable red tape and bureaucracy. The quality costs a bundle, of course, because of all the rework and waste, but that’s what taxpayers are for.

The “middle” is where coordination and control among the parts of the organization take place. When employees complain about “bureaucracy,” they don’t usually see the villain as their own boss or the CEO, but rather middle management and staff departments, such as finance. When they complain about a lack of cooperation, they most often see the problem stemming from departments other than their own and not being dealt with—in fact, sometimes magnified—by the middle managers to whom their and those other departments report. A complaint about disorganization is usually directed at inefficient work processes that cut across departments, such as the way staff groups and the line don’t communicate or coordinate well with each other.

This chapter is about the ability of workers to get their jobs done and, we focus largely on middle-organization issues since because that is where the most severe impediments to performance are seen to originate. It is where, on matters of performance, organizations with enthusiastic workforces most differ from their counterparts.

A further word about immediate supervision: immediate supervisors receive quite high ratings in just about all organizations. Our surveys show that 82 percent of employees are positive toward their managers’ technical skills (knowing the job). Although the rating of their human-relations skills is lower (73 percent), it is still much higher than the ratings we obtain on issues such as bureaucracy. In almost all companies, only about 8 percent of managers receive truly unfavorable ratings. That 8 percent can do much harm and require attention, but, by and large, we find first-line management to be bulwarks of organizations, even of those organizations that otherwise might be dysfunctional almost to the point of collapse.

It is telling that the attitudes of first-line managers toward levels above them and toward staff groups are often identical to those of their subordinates. Managers see themselves as “buffers” who protect their workers—and their performance—from the damage that those levels and groups can inflict. A frequent theme in senior management discussions and in the management literature is the presumed weakness of first-level management: they are blamed for various employee morale and performance problems. It makes sense intuitively to target those managers because they are in direct contact with the workers and might be relatively inexperienced in management. Yes, they are a big influence, but usually for the better! Therefore, intuition fails here and improvement steps, to the extent that they target the first level, are often misplaced.

Our focus on action in the middle does not mean that what happens at the top is unimportant. The CEO is often responsible for impediments such as excessive bureaucracy because she wants the organization to operate that way and she chooses the middle-level line and staff people who will do what she wants, but her role in those respects is often invisible to the rank and file. She therefore receives unjustifiably high ratings. However, action to resolve the problems, although directed at the middle, often must begin with her.

Put another way, the key impediments to job accomplishment are almost invariably a function of the culture set by senior management—especially the CEO—that is expressed operationally in the way the organization is structured and the way people are expected to interact within that structure. Our framework for discussing these matters will be “bureaucracy” because that encompasses much of what our survey data show as problems.

Ah, Bureaucracy! The Evil That Just Won’t Go Away

“I find it mind-boggling. We do not shoot paper at the enemy.”

—Admiral Joseph Metcalf, U.S. Navy (Ret.), on the 20 tons of paper and file cabinets aboard the Navy’s newest frigates

“The only thing that saves us from the bureaucracy is its inefficiency.”

—Eugene McCarthy, former senator from Minnesota

“Bureaucracy defends the status quo long past the time when the quo has lost its status.”

—Laurence J. Peter, former educator and author, and the father of the famous “Peter Principle”

What do employees mean by the bureaucracy they say they deplore? The issue is frequently mentioned in write-in comments, as shown earlier, as well as in focus groups. A number of insights emerge.

One area that workers often cite as a bureaucratic obstacle is the decision-approval process, which is seen as needlessly delaying decisions (such as decisions about resources employees need to do their jobs), detracting from the quality of decisions (often because the ultimate decision-makers are far from the action), and reflecting a distrust of employees and their ability to make the right decisions.

Another bureaucratic obstacle is the perceived obsession with rules and the enforcement of those rules. Employees see this as diverting the organization from its objectives and its ability to respond to changing conditions. It is the focus on means rather than ends that rankles workers here.

Let’s not forget good old-fashioned “paperwork” (real or its digital cousin) and the endless reports produced that employees see as utterly useless at worst (“All of this data is already available to Corporate, why can’t they access it themselves?”) or shrouded in mystery at best (“I know they want these reports, but I have never once been asked about them; what use is made of them?”).

Another facet of bureaucracy frequently mentioned is functional specialization, which is seen as narrowing the attention of units to only their own goals and creating boundaries between units that inhibit cooperation between them.

Of course, most people would prefer to operate with considerable autonomy, ignore the paperwork, and be able to rely on the cooperation of other units to effectively perform their jobs. That’s not news. It seems that the term bureaucracy is rarely used in anything but a pejorative sense. Much of the disdain for bureaucracy is well earned, but before we elaborate on its dysfunctions and recommend what an organization can do about them, we must first recognize why bureaucracy is, in significant ways, simply indispensable to organizations.

Can an organization survive for long without a clearly defined authority structure? Can it survive well without executives who are unafraid to use their authority? Of course not. People who argue for the elimination of bureaucracy in organizations—much of which concerns eliminating or drastically reducing power differentials—are arguing for chaos and organizational ineptitude.1

Only anarchists and theorists with no practical experience advocate chaos. Workers certainly do not. Therefore, although the majority of comments about bureaucracy concerns its downsides, we also receive complaints in a number of organization surveys about under-control (that is, too little bureaucracy)! Take these comments, for example:

I feel that the structure is disorganized, and I don’t feel as if I can get a clear answer.

We are completely disorganized and have no real planning when we roll out new products and services!

This “matrix” structure here is very confusing—everyone seems to think they can give me orders and they conflict with each other. How do I satisfy many masters? Who am I accountable to?

This place seems completely disorganized. Every change seems to be a knee-jerk reaction, and it seems that leadership usually has to go back and change things after they see that it hasn’t worked. There’s no stability. This place needs an overhaul. There are too many old Band-Aids over old wounds.

Who’s in charge here? Nobody seems to want to take responsibility for anything. It’s a spineless management, starting at the top. No leadership, all CYA.

There’s little documentation when programs change—it drives me crazy. We need at least a little paperwork! When people leave, the most elementary knowledge of what’s been done leaves with them.

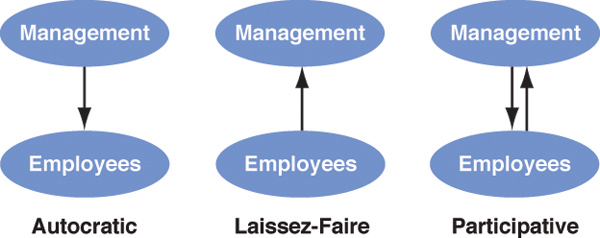

We are not arguing for the bureaucratic overkill that we have all come to know and hate. Chaos, however, is not the only alternative to that type of bureaucracy. In their studies of group functioning, social psychologists make a useful distinction between three types of leadership: autocratic, laissez-faire, and democratic. We call the last of these “participative” because democracy usually means that the leaders are chosen by the led and that concept has little applicability to the employee-management relationship. The key criterion is not how leaders are chosen but how they lead.

An autocratic style of management is characterized by domination of employees, inflexibility, and a belief that discipline and punishment are the most effective means to get most workers to work. This characterization can be applied to individual managers, such as compulsive, micromanaging autocrats, but also to the formal structures and processes that constitute excessive bureaucracy: approvals required for even the smallest decisions, a multitude of rules rigidly enforced, and work divided into extremely narrow tasks. Both at the individual manager and the structural levels, a fundamental assumption underlying autocratic management is a distrust of workers and their ability or willingness to do their jobs without a high degree of top-down control.

Autocratic management is not necessarily a malevolent management in the sense of unconcern for the economic well-being of workers. Some paternalistic organizations treat their workers well—in pay, benefits, and job security—but because “father knows best,” their managements are normally highly autocratic. These organizations are benevolent dictatorships.

At the opposite extreme from autocratic management is a laissez-faire style, which means “to let (people) do (as they choose).” Laissez-faire managers are divorced from their employees, uninvolved in what they do (either in a directing or a helping sense). These proverbial “weak” managers can, in their way, frustrate employees as much as autocratic managers.

On a structural level, laissez-faire management is the “anti-bureaucracy,” with few or no approval processes, rules, paperwork, or specialization by task. We know of no organization that is laissez-faire in its pure form, but those companies that even approximate this management style cannot endure: they soon disappear or are overhauled in order to survive. However, individual laissez-faire managers can survive for a while, especially in prosperous times when no one pays much attention to a department’s mediocre performance. When times get tight, these managers can no longer be tolerated and are removed.

Unfortunately, new executives brought in “to get this place under control” usually go to the opposite extreme: the pendulum swings, and they turn what was chaos into what employees feel is a virtual prison. The assumption is not just that things need to be tightened—of course, they do—but that workers somehow enjoy chaos and must therefore be managed with an iron fist. So, the frustration of employees formerly working under laissez-faire management turns into resentment because of the severity of the controls that have been imposed and the view that employees are untrustworthy. The resistance of employees to the new management style is usually characterized as “resistance to change,” which is highly misleading: it is resistance to needlessly autocratic management and the assumptions about employees that underlie autocracy.

The alternative to laissez-faire and autocratic management is participative management, whose key characteristic is mutual influence. Figure 8-1 shows the three management types depicted in terms of influence patterns.

Autocratic management is top-down, laissez-faire is bottom-up (“the inmates running the asylum,” as the joke goes), and in participative management, influence goes both up and down. The point of two-way influence is not that there is no boss or that everyone is boss. That is a laissez-faire environment, and it is not what we mean or what workers want.

In Figure 8-1, the arrow pointing down in participative management symbolizes the importance of certain traditional, top-down management principles. These principles are important to both the organization and its workers because the effectiveness of organizations and worker satisfaction require that, to the extent possible, there be clear and decisive direction from leadership; clarity of responsibilities, authorities, and accountabilities; authority that is commensurate with responsibility and accountability; unified command; and a clear approval process and rules governing acceptable employee behavior.

These principles are familiar and uncomplicated, and they encompass key aspects of what is normally termed bureaucracy. Although they are familiar, the principles deserve to be repeated because they are fundamental and, as we have said, they are seen by some influential modern theorists as largely out-of-date and dysfunctional, especially in the “new economy” or “post-industrial age” and with so-called Generation X, Y, and Millennial workers. These theorists talk about recasting traditional hierarchical organizations into all kinds of new forms, such as “spider’s webs,” “starbursts,” “wagon wheels,” and “shamrocks.”

Advocating seriously for the destruction of any semblance of hierarchy shows a lack of experience with the debilitating consequences of working in a directionless organization, getting conflicting instructions from different bosses, being unable to decipher who is responsible for what, or not having the authority to carry out one’s responsibilities. These severe obstacles hinder the performance of workers, whether they work in the “new” or “old” economy and whatever their “generation.”

However, the fundamental top-down principles can be taken to the opposite extreme, and that is the nub of the problem created by the bureaucracy and the bureaucrats that we abhor. A leader being decisive can sometimes come to mean rejecting all the subordinates’ input into decisions. Providing direction to an organization can turn into micro-management: instructing trained and experienced subordinates on how to do their jobs in every detail and requiring them to seek approvals for even the most minor deviations and decisions. Making responsibilities and accountabilities clear can result in rigid boundaries between departments, which makes collaboration impossible (the familiar problem of organization “silos”).

These examples depict the slippage of common-sense organization principles into a rigid machine model of bureaucracy. A machine cannot function without “a place for everything and everything in its place” and without external initiation and control. That’s the nature of an inanimate machine. But people are not machines or parts of machines: they can exercise judgment, have more than one job responsibility, and initiate activity. And they have emotions, such as feeling disrespected and angry when they’re treated as if they cannot exercise judgment, have more than one job responsibility, or initiate activity.

Workers want, and organizations require, just as much order as is appropriate to the need, and no more. Workers in a machine shop do not pretend that they can set corporate or divisional strategies, so they want leaders who know how to do that and do it well. But they can run the machines, and they are a rich source of ideas for how to make those machines run better and how to improve many other aspects of their work environments and work processes to increase performance. Managers who obsess about how their employees do their work and about minutiae such as the exact amount of time they take for rest breaks are not only doing what they shouldn’t be doing (meddling), but not doing what they should be doing: the planning, expediting, counseling, and coordinating that truly help employees get their jobs done.

The consequences of autocratic management—by an individual autocratic supervisor or a system that is excessively bureaucratic—are twofold in terms of worker performance. On the one hand, spurts in performance can be obtained by such top-down methods, but unless the pressure is continually applied and employees are supervised closely (and the supervisors are supervised closely), performance will soon dissipate. In other words, achieving an adequate level of performance becomes completely dependent on outside forces applied to resistant employees instead of on their internal motivation to do well and be proud of their work.

A second major consequence of autocratic management is a loss of brainpower: the ideas and ingenuity that the people who know the jobs well (the workers) can apply to improving performance. Autocratic management—whether by an individual manager or by an oppressive bureaucracy—makes the very costly mistake of assuming that wisdom is related directly and almost entirely to hierarchical level.

A Management Style That Works

Although autocratic and laissez-faire managing are different styles, both demotivate the great majority of workers, and both place severe obstacles in the way of their getting their jobs done. The research in this area strongly supports a third approach, which is participative. This approach is not simply a middle ground between the other two styles of management (a little less of this, a little more of that); it is really a fundamentally different method.

When moving away from autocratic management, some people adopt a laissez-faire approach, but this is not really leadership—it is an abandonment of leadership. Participative management is an active style that stimulates involvement, not a passive style that forfeits leadership. In an effective participative organization, no one is in doubt as to who is in charge. But that person expects employees to think, to exercise judgment, and not just do. Judgment is expected from workers in performing their specific tasks and in identifying and implementing ways to improve the organization’s performance as a whole. That is the environment in which impediments to performance can be removed and in which employee enthusiasm can flourish.

Our advocacy of participative management is based on more than academic theory or a democratic ethic. A great deal of research evidence demonstrates the superiority of participative management for performance. The evidence comes both from laboratory experiments and from field studies in real organizations. It has been collected in systematic ways since the 1940s. Also, contrary to what is commonly assumed, its value is not limited to America or other societies with a long history of democratic traditions.2

Over the past two or three decades, participative management has found widespread acceptance in industry, so our arguments, which were perhaps once considered radical, might now strike some readers as unsurprising, almost truisms. Unfortunately, much of the acceptance of this management style has been superficial: we find in our studies significant gaps between what organizations and managers say—and even believe—and what they actually do, as their employees report it. Yet, some managers are consistent: they not only practice an autocratic management style, they advocate it! They reject all arguments or evidence that participative management is anything more than a naive wish or fad. These are “old school,” command-and-control managers who believe that work is inherently distasteful to most people and that getting people to work and work hard requires a tough, autocratic approach.

Other skeptics employ a more sophisticated argument, asserting that the effectiveness of any approach to management depends on the conditions in which it used. Their contentions range from the obvious (for example, in case of a fire, does a manager engage his employees in a discussion of what to do?) to the less obvious, such as arguing that entire categories of work are best handled with autocratic methods.

Of course, there are specific conditions, such as many emergencies, where people don’t want to be asked for their opinions; they just want to be told what to do. It is ludicrous to think otherwise, and nobody does. And, who would suggest that new and untrained employees be given latitude as to how to do their work? The workers themselves don’t want that latitude—they want training and direction. Being left on their own at that time greatly frustrates them, and it is an example of laissez-faire, not participative, management. Finally, there are those few employees who simply don’t want to exercise judgment or give opinions under any condition; they are most comfortable taking and following orders, and that is how they need to be managed.

These are exceptions to the usual circumstance, which is trained and experienced employees working under normal, nonemergency conditions with a strong desire to exercise judgment while performing their jobs and to be asked for their views on how to improve performance. The exceptions do not negate the validity of the assertion about the overall superiority of participative management; they simply point to the need to avoid unthinking, mechanical application of this—or any—principle.

More serious and sweeping than the obvious exceptions to the rule (such as emergencies) is the argument that entire categories of work suffer if the management style and structure are participative. It is argued that autocratic management and hierarchical bureaucracy are better suited than participation to work that is simple and stable. “If the work is relatively simple and there is little need for coordination and problem-solving, it is possible that the control-oriented approach [what we are calling autocratic] will produce better results.... The control-oriented approach also works well if the type of work is highly stable so that it can be programmed to be done in the same way for a long period.”3

In other words, when there is no apparent need to think, don’t ask workers to do it.

The reasoning, if correct, would make participative management inapplicable to most blue-collar manufacturing jobs and routine white-collar work. In the most widely quoted paper employing this reasoning, “Beyond Theory Y,” the authors compare the effectiveness of authoritarian and participative styles in two manufacturing and two research laboratory settings. They conclude that:

Enterprises with highly predictable tasks [the manufacturing plants] perform better with organizations characterized by the highly formalized procedures and management hierarchies of the classical approach. With highly uncertain tasks that require more extensive problem solving [the two research laboratories], on the other hand, organizations that are less formalized and emphasize self-control and member participation in decision making are more effective.

They term this reasoning contingency theory, which is that the effectiveness of a management practice is contingent on other factors, such as the nature of the task.4

Contingency theory certainly makes intuitive sense, but it has a serious problem: it is contradicted by the legion of extraordinarily successful participatory initiatives in manufacturing plants throughout the world. For example, what is one to make of the extensive use by Japanese manufacturing companies of worker participation in shop-floor decision-making and the extraordinarily positive productivity and quality results that have thereby been achieved? The best-known of these applications have been with assembly-line workers in Japan’s automotive industry—hardly a condition of “highly uncertain tasks.”

Because of their success, the Japanese have been emulated in many countries, most frequently in manufacturing settings. That is where a change in the direction of participation has been most needed because manufacturing workers have been traditionally among the most autocratically managed. We don’t pretend that manufacturing workers can ever approach the kind of autonomy that, say, research scientists or sales representatives enjoy. The nature of manufacturing work—the need for standardization and precise coordination, for example—doesn’t allow for it, and workers don’t expect it. But that doesn’t mean that participation by workers is irrelevant or even harmful in manufacturing, as the contingency theorists appear to argue. For one, no matter how routine a job might appear, there is almost always room for worker judgment.

Second, although work may be highly standardized—to the point where a company wouldn’t want individual workers to deviate from the prescribed method—improvement opportunities invariably abound that workers can spot. These potential improvements can be fully discussed and carefully planned before they’re implemented. The results are encouraging and sometimes astounding.

One of this book’s authors, consulting with a plastics manufacturer, heard workers in a focus group comment on the enormous amount of “trim waste” in the plant. A participant said that he had long had an idea for a device to be attached to the cutting machine that would reduce the waste by at least half. The consultant reported this to the engineering department, and after innumerable meetings, the engineering department decided to try out the idea; it was made and installed on one cutting machine, and the trim waste was reduced by 82 percent! The device was installed throughout the plant. When asked why he hadn’t mentioned the idea before, the worker said, simply, “Nobody asked me.”

Jeffrey Pfeffer writes of a department in the Eaton Corporation where “...workers tired of fixing equipment that broke down and suggested that they build two new automated machines themselves. They did it for less than a third of what outside vendors would have charged and doubled the output of the department in the first year.”5

Tom Peters reports on an experience in the Tennant Company where the engineers devised a system to increase the efficiency of a welding department. The system, designed to reduce the need to store units during the welding process, would cost $100,000, which the company deemed too expensive. “A small group of welders tackled the problem. They designed an overhead monorail that could carry welded parts from one station to another so a frame could be welded together from start to finish without leaving the department... They discovered a supply of I-beams in a local junkyard and bought them for less than $2,000. In two days, they installed the monorail. In the first year of its use, the new system saved...more than $29,000 in time and storage space.”6

Anyone who has worked with manufacturing employees and kept his eyes open would not be surprised by these and the innumerable other examples of the contributions these people can make—if only they are asked! One of the morals of our story, for the theory and practice of management, is that there is often too much emphasis on human differences and not enough on human similarities. We hear of the differences between occupations, between generations, and between nations. (We used to hear much about differences between the sexes and the races, but those views are no longer acceptable to express, at least not publicly.) Many of the presumed differences make intuitive sense because they confirm long-held prejudices. But, they usually cannot withstand empirical tests. For example, Japan and Germany were historically highly authoritarian societies, yet industrial democracy has been flourishing in both countries for decades. Isn’t it so, the prejudice goes, that most blue-collar workers don’t have the will or the ability to use their minds to improve work operations? We know that assumption is dead wrong, and outstanding managers have known that for a long time.

With the few exceptions we have cited, participative management to our knowledge works under all conditions and for all segments of the workforce.

We will, in Chapter 12, “The Culture of Partnership,” show how participative management is an integral part of what we term, more broadly, a “partnership” culture.

Layers of Management

Central to a discussion of authoritarian and participative management is the matter of “steep” or “flat” organizations. Organizations that workers feel to be excessively bureaucratic are typically steep: there are many layers in the management hierarchy, with each level supervising relatively few employees. A flat organization is, of course, the opposite: there are few layers in the management hierarchy and, generally, a larger number of employees report to each level.

In steep organizations, workers are notably caustic and cynical about the number of management levels. The criticism does not indicate that workers don’t want to be managed—they do. They simply see no added value—they see value diminished—by the many management layers. In addition to problems of over-supervision (because the boss supervises only a small number of employees, what else does the boss have to do but supervise?), their major gripes concern the large costs to the organization of so many managers (salary, expensive office space, and so on), the way these steep hierarchies inhibit timely decision making, and the way they inhibit clear communications up and down the organization. Here are some representative employee comments about management layers. They are in response to the question, “What do you like least about working here?”

All these levels of management and their cost! What are their jobs but to be messenger boys and work like crazy to keep their jobs? They have very few people to supervise so they’re all over their employees.

The unneeded multiple levels of management and the politics that exists. Managers that only care about themselves and not the process or the people are useless. I see very little value add of all these levels. If you asked me who my real manager was, I would say two levels above the one they call my immediate manager. Essentially, I don’t know why they need him and his manager.

There is a lack of clear communication between all these multiple levels of management, creating confusion about goals and achievements. It’s like the telephone game. By the time the message gets to us, it’s garbled.

A question we often see asked, in answers to open-ended survey questions, is, simply, “What do all these people do?” It is actually a good question, and one that is occasionally asked by the people who occupy those many layers of management!

The two major reasons given by companies for their steep organization structures are control and functional specialization. It’s interesting that the number of employees reporting to a supervisor is referred to as his span of control. The more control that is desired (in other words, the less people are trusted to control themselves), the fewer the number of people that report to managers at each level, and thus the greater the number of management levels that are required. In that sense, the steep organization consists of checkers upon checkers.

In addition, the role of managers in each layer of the hierarchy is to coordinate with other managers of interdependent departments. The finer the division of labor (specialization or “functionalization”) in an organization—the more each individual or department performs just one function rather than being responsible for the “whole thing” (for example, a whole product or a whole customer)—the greater is the interdependence, and, consequently, the greater the need for coordination among the parts and for layers of management to do the coordination. In a completely functionalized organization, no one is responsible for the “whole thing” except the very top, to which all the functions report through their individual, and usually multilayered, hierarchies. We return to this matter in detail in the section “The Benefits of Self-Managed Teams,” where we show how a team can within itself perform a variety of functions and thus make possible much flatter organizations.

Not much research has been done that systematically and directly tests the relationship between the number of management layers and the performance of organizations. One study, performed by A. T. Kearny in 1985 that covered 41 large companies, found a strong negative relationship between the number of management layers and long-term financial performance. The organizations with outstanding performance had an average of 7.2 layers, versus 11.1 for the others. They also had 500 fewer staff specialists per $1 billion in sales.7 In another study, researchers found that companies with average spans of three (necessitating a steep hierarchy) spend almost four times as much to manage each payroll dollar as do firms that have average spans of eight.8

Many case studies reinforce the quantitative research findings: companies with records of outstanding long-term performance have extraordinarily flat structures. Nucor Corporation is a leading example of this. As F. Kenneth Iverson, the chairman of Nucor, has said, “The most important thing American industry needs to do is reduce the number of management layers....[It’s] one thing we’re really fanatical about. We have four management layers. We have a foreman, and the foreman goes directly to the department head, and the department head goes directly to the general manager, and he goes directly to this office.”9 Another example is the Dana Corporation, which went from 15 management layers (and barely profitable) to five layers (with greater profit).

Our discussion in the preceding chapter is relevant here, too, since many organizations with flat structures, such as Nucor, are characterized by a strong sense of purpose and principles. A powerful company culture built on a belief in the importance and value of what it does and shared norms as to what is acceptable behavior is in itself a control mechanism that lessens the need for external controls such as layer upon layer of management. And with fewer controls comes greater employee commitment and enthusiasm which, in turn and in the manner of a virtuous circle, requires fewer controls to operate effectively.

Perhaps a major reason companies with enthusiastic workforces are more successful is simply that it is so much less costly to manage them. Steep structures are especially costly, but not only because of the compensation and expenses of the occupants of the many hierarchical layers. Time and manpower spent responding to the checking and meddling of managers and their staff groups, directly or through endless report requests, is another expense source. Yet another is the inherent delays in the flow of needed information through the hierarchy and in decision making; these delays reduce the timeliness and quality of response to problems and to a changing business environment. Last, but by no means least, as we have said, is employee frustration and demotivation. There is no such thing as an enthusiastic workforce in an excessively layered organization.

The Benefits of Self-Managed Teams

A goal of every organization should be to flatten the structure as much as possible, probably to somewhere between five and seven levels for the total organization, and just three levels in any single facility.9 Flat organizations lend themselves to decentralized decision making because managers have less time to get involved in the minutiae of day-to-day decision making. Organizations that don’t take advantage of this—that simply cut managers and management levels without consciously and deliberately moving authority down the line—find that the workload of the remaining managers has increased enormously, the quality of their work has likely decreased, and their work lives have become correspondingly miserable. These organizations eventually add back managerial staff, which causes costs to balloon once again. They accomplish worse than nothing because reorganizations and re-reorganizations are expensive, and pendulum swings in structure foster (or reinforce) a cynicism in employees about their management’s competence.

The decentralization that allows for effective flattening of an organization (not just head-chopping) is, by far, best accomplished by establishing self-managed teams, or SMTs. SMTs are teams of workers who, with their supervisors, have delegated to them various functions and the authority and resources needed to carry them out. Ideally, the team does the “whole thing”—builds a whole product or provides all the services for a defined customer or set of customers.

SMTs of one kind or another are required for effective flat organizations, if for no other reason than that some of the work performed by the eliminated management layers actually does need to be done!

Increasing control by, not of, employees is the essence of the SMT approach to management. This self-control is a product of less need to obtain management’s approval for many decisions because these have been delegated to the team (“vertical” autonomy). There’s also less need for the group to interact with other units to obtain their assent to decisions because so many functions—traditionally distributed among a number of departments—are performed within the team and, therefore, are under control of the team (“horizontal” autonomy).

Performance is further enhanced in well-run SMTs by the emergence of “group norms,” in which members exert a strong influence on each other’s behavior. This is especially pronounced in the case of nonproductive employees who are subjected to internal group pressure to perform, thus reducing the need for management’s intervention. (Here’s a reminder for those interested in improvement in the nation’s schools: We referred previously—in Chapter 4, “Compensation”—to the advisability of gainsharing for the compensation of teachers and mentioned how teachers within a well-designed gainsharing system—such as one with participative teams—would be much more likely to both assist, and, if needed, put pressure on, their low-performing colleagues to improve.)

There is considerable variability in the number and kinds of management tasks delegated to the teams. Any SMT worthy of its name will have a great deal of say over work methods, work scheduling, production goals, quality assurance, and relationships with the team’s customers (external or internal). But some organizations have gone considerably further and have delegated human-resources decisions, such as hiring employees, to the teams.

And there are large differences in the degree to which teams perform the “whole thing.” At one end of the continuum are organizations such as Volvo, which experimented with workers building an entire car. At the other end are organizations such as Toyota, which has given teams a lot of authority, but the actual work done has remained highly fractionated.

In reviewing the research on the effectiveness of SMTs, it appears that the ideal SMT is one that:

• Produces the whole thing for an identified customer or set of customers with whom the team interacts.

• Has clear goals for which it is accountable.

• Contains within it all the skills needed to get the job done.

• Has access to the information and has control over the resources it needs to complete the job.

• Receives rewards based on team performance.

In other words, under ideal circumstances, the team operates like a small business whose members are highly involved in its management and in the sharing of its rewards.10

Of course, all of this can be taken to an illogical extreme. Should each small team in a company have its own computer specialists for programming, computer repair, and so on? That would be quite a luxury and only rarely appropriate. For the sake of efficiency and depth of resources, some degree of centralization (sharing) of IT services is required. Should a team of employees in an automobile-assembly plant assemble an entire car, rather than use the traditional mass-production method? The idea sounds enticing, and it has been tried in a few places, such as in the Uddevalla, Volvo, plant in Sweden. The research on this manufacturing model, such as that done by Dr. Paul Adler of USC, concludes that it can never achieve the levels of efficiency of well-run mass-production automobile-assembly plants.11

The Toyota paradigm is instructive because it does have teams, and it strongly encourages—in fact, is renowned for—employee participation: employees are encouraged to suggest ways to improve the manufacturing process to increase quality and reduce waste and inefficiency. Furthermore, the teams have responsibility and authority for various duties, such as quality control, scheduling shifts, maintaining and repairing equipment, record keeping, measuring performance, and ordering supplies. Workers have the authority to stop the line when they see a defect or problem. One of the principles of the Toyota production system is that people are intelligent and motivated to do a good job, and they will do that and more if they’re given the right tools and adequate authority.

Nevertheless, Toyota’s assembly lines are still highly fractionated and standardized. The teams in that company are responsible for a few stations on the assembly line, not the “whole thing.” Volvo represents a rejection of the scientific management principles that govern the structure of the traditional mass-production assembly line. Toyota, for the sake of efficiency, accepts those principles but puts workers as a team largely in charge of the line.

Manufacturing the “whole car” is an example of taking the SMT concept too far. But the number of organizations in which the concept doesn’t go far enough greatly outweighs such examples. These are the instances where SMTs and other participative mechanisms are largely antithetical to the organization’s real culture and outside the mainstream of its business.

Many companies claim they have participative efforts underway but, unfortunately, those programs too often are little more than ornaments—worn by organizations to enhance their image (and even self-image), but bearing little relationship to the organization’s reality. Office or plant walls display signs and slogans that preach participation and the importance of people, but the treatment of workers daytoday, even when there are SMTs, makes these signs appear to be just company propaganda. In a 1997 study of the General Motors plant in Linden, New Jersey, for example, Ruth Milkman found that the company had introduced a number of participative philosophies and methods. However, despite company slogans calling for involvement and empowerment, workers at Linden “...were told they could pull a cord and stop the line to prevent defective products from proceeding, but those who did so were criticized by foremen and eventually stopped trying.”12

The situation in Linden is reminiscent of other participative efforts, such as many formal suggestion programs that fail or just limp along because of the gap between their promise and what employees experience in practice. It has been said that suggestion programs raise morale at two times: when you put them in, and when you take them out. Who can dispute the worthiness of soliciting improvement ideas from workers and paying them for the ideas that the company adopts? Despite the promise, suggestion programs often frustrate employees.

By contrast, Toyota’s suggestion system has been fabulously successful. Toyota employees, on the average, are reported to contribute 50 or more ideas per person per year, and 80 percent of those ideas are implemented. Essentially, all employees participate. In U.S. companies, however, the participation rate in suggestion programs is about 8 percent (2.4 ideas per person per year), and only about one-third of the suggestions are implemented. The difference is that Toyota has a highly participative overall culture, and its suggestion system is integral to its continuous improvement efforts.13

The lesson from Toyota, therefore, lies not just in the mechanics of its suggestion programs or the way it structures teams. It is that, for this company, the programs are not add-ons or symbols of the way Toyota wants the world to believe that it manages people. It is not public relations. It is the way Toyota actually treats its workers, day in and day out.

It is critical, furthermore, that participative mechanisms be at the heart of the business as well as the culture. Self-managing teams do best when management provides them with clear direction, high performance goals, and clear accountabilities.14 You might recall that participative management—as contrasted with laissez-faire—contains an “arrow down,” which is direction from above. That arrow ties the team to the goals and strategies of the business.

We, therefore, prefer the term “self-managed” to “self-led” teams. We have never observed an effective SMT with a weak leader or one whose top priorities did not include the priorities of the business as a business. In other words, it’s not all fun and games. In fact, what is really not fun for workers is to work on things that are of little importance. In some applications of SMTs, one gets the feeling that the team, with its endless team-building exercises, becomes almost an end in itself rather than a means for the achievement of business ends. “I’ve seen too many groups go off on wilderness excursions or use ‘structured team-building experiences’ to try to turn a group into a team,” says consultant Jim Clemmer. These approaches don’t work because they’re not focused on business and performance issues or the broader organization context and focus. They don’t get any real work done.”15

To summarize, self-managed teams and other participative mechanisms can achieve more than brief bursts of enthusiasm and performance only if they do not stand alone: they must be exemplars of—not exceptions to—the broad organization culture, and they must clearly and directly support the achievement of business objectives. Failing those, they will shrivel and, to all intents and purposes, die. But when they are integral part of the organization—not something tacked on for show—they are, by far, the most effective way to organize.

Telecommuting: Yahoo Bans Work-From-Home

In late February 2013, as we were completing the manuscript for this book, Melissa Mayer, the recently appointed CEO of Yahoo, issued an edict banning the practice of allowing Yahoo’s employees to work from home. Employees would have to start showing up at their offices beginning in June. We stopped the presses on this book so that we could comment on this action in the context of the findings and point of view of the book. It is especially relevant to the arguments we presented in this chapter regarding the organization’s impact on employees’ ability to get the job done and work autonomously.

The announcement banning work from home, or “telecommuting,” was, of course, controversial, eliciting a few supportive, but mostly negative, reactions in the blogosphere and other media. The most critical comments portrayed the edict as a huge step backward in the management of employees, with particular reference to the better work-life balance that working at home made possible for everyone who took advantage of it, but particularly for women with small children. Many of the critics spoke of their shock that a woman would take this step. There was also no shortage of reference to a new and different “generation” of worker for whom Ms. Mayer’s action would be infuriating because that generation placed great emphasis on the job autonomy that working at home helped provide.

Supporters of the action tended to stress that Ms. Mayer is smart and experienced and is a CEO exercising her prerogatives, and that this was an important step in her major task: making Yahoo—universally considered to have become a laggard in a fast-moving industry—a leader again with substantial revenue and profit growth. The company had had five CEOs in the past five years, both a sign and a source of its problems.

We are by no means experts on Yahoo, but we know something about management and the steps they often take to deal with performance problems and the consequences of those steps. We mentioned a number of times in this book that cracking down on malingerers is one of the most common actions executives take—especially new executives—when they feel they have to whip an organization into shape. We will argue that that was likely one of Ms. Mayer’s major reasons for her action, although that was not the reason given. Companies frequently clothe in more acceptable language policies and practices they fear will not be received well. A consultant convinced one large corporation we studied that its factory workers were doing much less work than was possible or standard. Using time-study, the corporation introduced significantly increased productivity requirements but called it a Methods Improvement Program. It had little to do with improving methods and everything to do with getting workers to work harder.

In the announcement sent to Yahoo employees, the reason given for stopping telecommuting was to increase face-to-face interaction among employees to boost innovativeness and improve worker morale:

To become the absolute best place to work, communication and collaboration will be important, so we need to be working side-by-side. That is why it is critical that we are all present in our offices. Some of the best decisions and insights come from hallway and cafeteria discussions, meeting new people, and impromptu team meetings.

Interaction and Innovativeness

The research over the years on interaction has been quite clear: when people are working on interdependent tasks, interaction significantly improves innovativeness, and face-to-face interaction, despite all the improvements in communications technology, remains the gold standard. It’s not that technology can’t be used well for facilitating interaction in more formal, planned settings. It’s that a whole lot of innovativeness is a result of unplanned, accidental encounters and discussions. Furthermore, communications are significantly improved when verbal communications are supplemented by body language, so there is no substitute for being able to size up one’s colleagues face-to-face. And then there is learning, much of which is done on the job and, for almost all jobs we can think of, requires good role models—both colleagues and bosses—from whom one learns in the course of face-to-face observation and interaction.

Modern technology, of course, supplements informal interaction in very important ways, such as continuing the exchange when the participants are separated geographically. But it cannot fully replace it. Although we might like to think that technology is especially beneficial for people at a distance from each other and might otherwise not communicate, the finding, not surprisingly, is that people are much less likely to phone or email or IM for a discussion with people they haven’t met face to face.16

Ms. Mayer, therefore, has a strong case in her argument that, for promoting innovativeness, getting her employees onsite should be of considerable help. How about the case for raising morale? Here, her position is considerably weaker.

Employee Morale, Employee Work Ethic

While some significant morale benefits can be found for onsite work—we’ll get to those shortly—they are overwhelmed by the tremendous advantage to quite a few people of having the flexibility that at-home work provides. Keep in mind that when in this book we speak of the three goals of people at work, we are careful to stress that these are work-related goals—that is, we are not referring to the many and extremely important personal needs and desires of people. There are, for example, the needs of parents of small children; the desire to avoid the frustration and the cost of long commutes; and the possibility, because of the availability of telecommuting, of living distant from the office, in a city of one’s choice.

Because these personal needs and desires are so important and can so much more easily be satisfied by working at home, they overwhelm the advantages to morale of working with one’s colleagues face to face. Those morale advantages are not at all trivial; they’re just of a lesser magnitude when faced with the requirement to be at the office every day. Among the other morale advantages of being onsite—in addition to the increased innovativeness that comes from such interaction (important to employees, not just the company)—are a decreased sense of isolation; quite a few people become lonely working day after day alone, missing the camaraderie that comes from the interaction with colleagues. And the isolation can be compounded by a sense of being out-of-sight-out-of-mind when it comes to selection for advancement and other desirable assignment opportunities.

Ms. Mayer’s claim that her new policy would raise morale is likely broader and deeper and more transformative than portrayed by the preceding examples, and it relates to our comment about executives “cracking-down.” Former and current Yahoo employees, reports the New York Times, portrayed a culture “...where employees were aimless and morale was low...[a company] out of competition with its more nimble rivals.” In the tech world, it seemed almost an embarrassment to say you worked for Yahoo. “I’ve heard she wants to make Yahoo young and cool,” commented one former employee.17

But it was clearly not simply an old and stodgy culture that Ms. Mayer wanted to change. She noticed that Yahoo parking lots and many offices were nearly empty during the work day. People were either not coming into work at all or were leaving early. Approximately 200 employees worked at home full time, and some of these were suspected of running their own-start-up businesses on the side.18 According to media reports, Mayer, upon reviewing employees’ Virtual Private Network logs, concluded that employees were connecting to the office much less frequently than they should be.19

So, in addition to her other reasons for the edict, Ms. Mayer’s actions almost certainly reflect a distrust of the work ethic and dedication of some—perhaps many—Yahoo employees and the need, therefore, to bring them to the office where, in addition to promoting the interaction she speaks of, they could be supervised more closely. Or they will quit, which, in some cases, might not be an undesirable result. She wants, in other words, to bring discipline, as she sees it, to the organization, and this may be one of a series of steps in that direction that she is taking or contemplating.

As of this writing, we have had no direct access to the employees of Yahoo and therefore don’t know firsthand what their reactions have been. Our best guess is that the reactions have been strong and mixed. Some will no doubt feel, “It’s about time!” The employees seriously inconvenienced by the move—such as those who will now have to commute long distances every day and parents who will have to make other arrangements for their children—are not going to be happy. They’ll probably be quite angry considering the apparent suddenness of the action, the blanket nature of the edict, and the fact that it is something being taken away and therefore seen as a promise broken.

As we have said, a major mistake managers often make is to generalize from the few to everybody. They don’t see the shirkers as a small minority and may even believe that it is the genuinely committed who are few in number; therefore, they deem it important that just about everyone be watched closely. Another source of negative reaction to the edict, then, should be the resentment of hard-working employees who believe they are being treated as untrustworthy.

Telecommuting and Performance

What have we learned from research about the performance of people who work from home? We don’t know what a study would reveal at Yahoo, but systematic studies of the performance of telecommuters show quite consistently that they are more productive—they produce a larger amount—than their counterparts in the office. Although the reverse is likely true when it comes to innovativeness, we can say with certainty that there is no evidence that allowing employees to work from home is a recipe for wholesale shirking. A major reason for the higher productivity at home appears to be that at-home workers work more hours as the boundary between their home lives and work lives blurs. A University of Texas at Austin study found that those who work from home “add five to seven hours to their workweek compared with those who work exclusively at the office.”20 Some of the additional hours are also a result of the reduction in commuting time.

A meta-analysis—a systematic “study of studies”—of 46 pieces of research on telecommuting21 finds that “telecommuting had modest but mainly beneficial effects on employees’ job satisfaction, autonomy, stress levels, manager-rated job performance, and (lower) work-family conflict. Although a number of scholars and managers have expressed fears that employee careers might suffer and workplace relationships damaged because of telecommuting, the meta-analysis finds that there are no generally detrimental effects on the quality of workplace relationships and career outcomes. Only high-intensity telecommuting—where employees work from home for more than 2.5 days a week—harmed employee relationships with coworkers, even though it did reduce work-family conflict.”

Conclusions and Recommendation

On the basis of the evidence, can there be any question as to what the right answer is for companies wrestling with the issue of telecommuting? Unlike many management decisions involving people, the answer is, at least for us, clear.

Let’s begin by restating a fundamental proposition of this book: there is little real conflict between the goals of the overwhelming majority of workers and those of their employers. It is in the nature of people to want to work and to do well for their companies. Very few people are inherently lazy, greedy, or dishonest. It is primarily management that, by it practices, dampens or destroys motivation, especially when those practices derive from the assumption that most people don’t want to work—certainly not hard—and have little concern for their companies. Unless there has been some awful incompetence in the way people have been hired at Yahoo, it is certain that the overwhelming majority of its employees would be eager to work not only hard but probably in excess of what would normally be expected of them.

If our reasoning is accepted, we conclude that telecommuting in Yahoo will be a problem only to the extent that management makes it a problem. Otherwise, it can be a boon to both the company and its employees. Among other reasons, the company will gain because:

• It will be able to attract and keep employees for whom the ability to work at home is a major plus. And, in that respect, the company’s overall reputation as a good employer will be enhanced.

• Employee morale will increase, and with it the overall performance that we have demonstrated comes from higher morale.

• Employees will work more hours, and employee productivity—the amount they do—will improve.

• The company will save on real estate and related costs.

Employees will gain in the ways we have described, which are primarily flexibility, for those who need or want it, and avoiding the frustrations and costs of commuting.

What are the downsides? Frankly, we can’t think of any of any significance if telecommuting is managed properly. From what we read about Yahoo, it appears that, in quite a few instances, it just wasn’t managed. Hence, the too-common company reaction: a swing from what appeared to senior management to be a laissez-faire environment—“Do what you like”—to the opposite extreme: a ban on all telecommuting.

What do we mean by proper management? It is, of course, neither extreme, but rather an approach that recognizes the legitimate needs and wants of employees and seeks to satisfy them in a way that not only will not damage the company but will be profitable to it. We have called this a “partnership” approach—or culture—and it will be described fully in Chapter 12. The position that Ms. Mayer has adopted on the telecommuting issue is characteristic of another approach, also to be described in that chapter, which we call “adversarial.”

The policy we recommend is, essentially, a variant of “flextime.” Under traditional flextime, there is typically a core period when employees are required to be at work—say, 50 percent of the working day—but they can choose which hours of the rest of the day they will be at work, as long as the total number of hours adds up to a full working day. The practice is very well received by employees because of the flexibility it gives them in their starting and stopping times. Although it’s usually applied to working hours in a day and does not include working at home, the basic flextime concept can be applied to telecommuting. First, as regards core time, the application would be days in the week rather than hours in the day. And the flexible days could be worked at home. The approach would therefore provide for both workplace interaction and telecommuting for those who want it. And it would not be laissez-faire—come in whenever you want—because there would be a core set of days in the week that employees would be expected to be at work. Keep in mind that the Gajendran and Harrison (2007) study found that working relationships do suffer when employees worked from home more than 2.5 days per week. The core would be not just a number of days, but specific days, to ensure the opportunity for interaction.

How would our proposal be received by employees? With a great big hooray! Keep in mind that employees want their company to succeed. There must be no small number of Yahoo employees who believe that the previous policy—to the extent and in the places where it was laissez-faire—was nutty and they would want it changed. Further, the evidence is that it is just a very small number of employees who would choose to work from home full-time. The great majority want to interact with their colleagues, and they don’t want to be forgotten for promotions and choice assignments by the powers-that-be. Even those who have to commute long distances to work consider it a blessing to be able to spend 1–2 days a week at home.

There are exceptions, of course, and these should be handled on a case-by-case basis. Among the exceptions are those who are truly lazy or who are exploiting Yahoo’s beneficence to pay them while, say, they get a startup going. We’ll get to these—the shirkers—in a moment. There are those for whom working at home fulltime (or nearly so) is seen as a necessity, such as some parents of young children or people who will have to move their residence. The best rule for managers in these cases is this: use your best judgment. We are personally unaware of any such situation in which a competent manager was not able to make a sound decision, such as permitting an exception, but also, in some cases, the employee having to leave the job.

What we are proposing cannot be administered in a centralized way, other than in very small companies. The policy should be handled by individual managers and their teams—hopefully SMTs as we have described them in this chapter. Tasks, individuals, and the dynamics among individuals are different across areas of a business, and specifics have to be tailored to those conditions. The tailoring is best done by people familiar with the conditions. The role of higher-level management, including the very top, is to provide ground rules and guidance to the managers and teams, such as the stipulation that core days at the office are expected. Because there are no doubt jobs and departments in which employees must be onsite, every day, and for all normal business hours, there should obviously not be a requirement that the opportunity to telecommute be made available to everybody.

What about the shirkers? Part of the guidance from top management involves how those people are to be dealt with. In a word, as we said earlier in this book, firmly. But, as we also said, the team itself will help management deal with the issue. In a self-managed team in a partnership culture, the pressures that colleagues place on each other shift from “don’t do any more than you have to” to “let’s do as much and as well as possible.” It’s hard for individuals to resist those pressures, and for those individuals who do, the company’s disciplinary procedures are brought into play.

We speak of partnership as the culture where what we propose will operate best because it is congruent with, and reinforces, that culture. There is another respect in which context is extremely important: the extent to which the organization, as a whole, has a clear sense of direction with challenging goals that can be translated into clear, challenging, and credible goals for each of its subparts. We don’t know that Yahoo can be described in that way, but, if not, or not in certain parts of the company, the idea of people being required to show up at the office doesn’t make too much sense. If they don’t have much to do at home, is it better to not have much to do in the office and fake it? We’re stating the case somewhat facetiously to make this point: changes in practices, such as telecommuting, won’t by themselves solve fundamental problems and may distract from them. Telecommuting, as we have proposed it be implemented, can be a terrific way to serve the company and its employees. But it also has to be seen in the context of the culture of the organization and the overall effectiveness with which the business is being run.