Chapter 4. Give me a Reason Not To

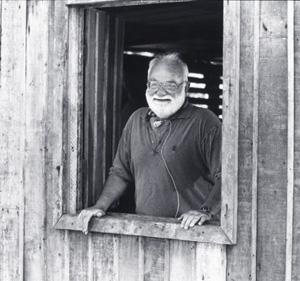

Walter Murch’s office, upstairs in a converted barn.

From: Walter Murch

Subject: Final Cut Pro

Date: 6/2/02 10:44 PM

To: Steve Jobs

Dear Steve Jobs:

Greetings, and thanks for all you have done for the world through Apple and Pixar, and most likely many other things I don’t know about, but from which we all have reaped an indirect benefit.

My name is Walter Murch, and I am a film editor and sound mixer, working mostly in the Bay Area for the last thirty-three years. I started out with Francis Coppola and George Lucas in the early days of American Zoetrope, back in 1969 when we all moved up to SF from LA.

I am going to be editing “Cold Mountain” for Anthony Minghella, for whom I edited “The English Patient” and “The Talented Mr. Ripley.” The studio is Miramax. The film is based on the best-selling book by Charles Frazier about the closing days of the American Civil War. We start shooting in the middle of July. The film stars Jude Law, Nicole Kidman, Renée Zelwegger, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Donald Sutherland, and will be an expensive, high profile project.

We intend to use Final Cut as our editing program, and we have had conversations with a company in LA, DigitalFilm Tree, about advising us. They have personal links to people at Apple who were instrumental in the development and promotion of Final Cut, and when initial approaches were made in March of this year, the attitude at Apple was very receptive to the idea of our collaboration, to say the least.

But last week there was a follow-up phone conference between Ramy Katrib at DFT and Apple. This time around, Apple declined to give us the logistical support that they were enthusiastic about offering a couple of months ago.

I am still optimistic that this will work out. I have been using Macintoshes in the cutting room since 1986, and “English Patient” was the first digitally-edited film to win an Oscar for editing. My assistant Sean Cullen is very much for it, and extremely knowledgeable about how to make sometimes difficult situations flow easily. Ramy Katrib at DFT is also still enthusiastic. Is there anything that you can do to help us?

Anthony Minghella is a good friend of Steve Soderbergh’s, and in private conversations (notwithstanding the Soderbergh/Final Cut ads that Apple is currently running) not only was Soderbergh’s advice to Anthony not encouraging, it turns out that he (Soderbergh) will not be using Final Cut on his next film. If we now find that Apple itself won’t offer us support, even in token, it makes it more difficult for me, politically and technically, to move forward with Final Cut Pro on “Cold Mountain.”

I hope that you will see the advantage to everyone in somehow making this work.

My sincere good wishes, and thanks for taking the time to read this email, Walter Murch

The following morning, less than eight hours later, Steve Jobs sends a brief email reply to Murch. He writes that someone from the Final Cut Pro team will contact Murch. Jobs then asks Murch why director Steven Soderbergh no longer feels favorable to Final Cut Pro.

Murch tries to find his own answer to that question. He contacts Sarah Flack and Susan Littenberg, editor and assistant editor, respectively, of Soderbergh’s Full Frontal.

June 3, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Talked to Susan Littenberg who assisted Sarah, even though she is an editor herself, and is working on Solaris. They have reservations about FCP, don’t think it is ready for working on features.

Later that same day, as Steve Jobs promised, an email exchange ensues between Murch and Apple’s top Final Cut Pro product managers, Bill Hudson and Brian Meaney.

Date: Mon, 03 Jun 2002 17:12

Subject: Final Cut Pro

From: Bill Hudson

To: Walter Murch

CC: Brian Meaney

Dear Mr. Murch,

Our friends at Digital Film Tree tell us you are exploring the use of Final Cut Pro for your next movie, “Cold Mountain.” We are flattered that you would consider using our product for this important film and we’d like the opportunity to speak with you so we can fully discuss Final Cut Pro’s capabilities and limitations.

Let us know how best to reach you.

Regards,

Bill

------

Bill Hudson Strategic Accounts Manager

Professional Applications

Apple

From: Walter Murch

Subject: FCPro

Date: 6/4/02 3:40 PM

To: Bill Hudson

Dear Bill:

Good talking to you today. I have passed your email and phone number on to my assistant, Sean Cullen, and he will be contacting you in the next day or so to discuss in more depth the issues that you raised.

I am excited about the prospect of using Final Cut Pro on Cold Mountain, and particularly excited by the prospect of helping the program evolve to a point where it becomes the standard in the film industry.

All best wishes,

Walter Murch

A meeting is set up for June 18 in Berkeley among Murch, Cullen, Hudson, and Meaney to discuss Final Cut Pro and how a working relationship between Cold Mountain and Apple might be structured. A few hours later Murch gets a discouraging follow-up email from Full Frontal assistant editor, Susan Littenberg:

Date: Tue, 04 Jun 2002 18:33

Subject: Re: Thanks

From: Susan Littenberg

To: Walter Murch

Walter,

It was an honor to converse with you. A few more points have come to mind that I’d like to share, and possibly coerce you to seriously consider trying FCP on a small project before putting it to the test on a big feature...

Littenberg warns Murch about “real time” rendering of effects in Final Cut Pro, such as dissolves between shots. FCP can easily preview such an effect on a computer screen, but to see it on a TV monitor, or on tape, requires “rendering,” or being saved permanently, which is time-consuming. Since Full Frontal originated on digital video, not film, Littenberg expresses doubt whether FCP can even work in 24 frame-per-second film mode.

The following day Murch makes a foray to the shop Steve Jobs built. No, not Apple, but his other company—Pixar Animation Studios in Emeryville, California. Jobs bought Pixar from George Lucas in 1986 when it was the computer graphics division of Lucasfilm, Ltd. The success of Toy Story in 1995 put Pixar on the map. Over the following eight years Pixar released A Bug’s Life, Toy Story 2, Monsters, Inc. and Finding Nemo—five blockbusters with an accumulated worldwide box office gross of more than $2.5 billion. And that figure doesn’t include revenue from home video, DVD, or merchandise sales. Pixar combines original storytelling, its highly advanced RenderMan software, smart filmmaking, and voices of the stars to mine an ever-deepening, gold-veined niche in animation. The company is a child of two first cousins: the adventurous, tradition-breaking Bay Area spirit that brought Lucas, Coppola, Murch, and others from Los Angeles to San Francisco in the 1960s, and the entrepreneurial high-tech inventiveness of Silicon Valley, only an hour or so to the south, personified by Apple CEO Steve Jobs.

The entrance to Pixar Animation Studios, where Murch went to learn more about Final Cut Pro.

Like a perfectly constructed haiku, it’s as inevitable as the seasons that Murch should go to Emeryville so he can run his idea of using Final Cut Pro past two Pixar editors he has known for many years: Torbin Bullock and Robert Grahamjones. After a few email exchanges they invite Murch for lunch and show-and-tell.

Emeryville had always been a small but puissant blip on the Bay Area map. Even before Pixar arrived, Emeryville was a host for entertainment services, just of a different sort: gambling, card clubs, the Chinese lottery, and the first dog races in the U.S. Its mayors and district attorneys traded places with each other, often with a jail stint in between for extortion, rackets, and other underworld activities.

Emeryville cleaned up in the 1970s and went straight, using its well-developed political muscle for broader economic benefits. First it courted high-tech companies needing to stretch out beyond the Santa Clara/San Jose area. Then the town sought out biotechnology and software companies such as Chiron and Sybase to locate here. When Pixar outgrew its home in nearby Point Richmond, a similar post-industrial bayside town, Emeryville made Jobs a tax-incentive, development offer he couldn’t refuse. In 1998 Pixar broke ground on a 225,000-square-foot facility, built from scratch on the site of an old Del Monte cannery right across the street from Emeryville’s 1903 Deco-style, copper-domed City Hall.

Pixar’s two-story building is surrounded by well-kept lawns, and its masonry commingles 515,000 specially made ruby, mojave, coral, brown, and black bricks. The pattern of shapes and colors seems to be random, selected by some imaginative, free-associating bricklayer. One row is set ends out; the next five rows are placed the long-way. But there is a visual code embedded in those walls. Horizontally set bricks are the rectangular shape of digital video pixels, the ones laid square the shape of computer graphics pixels. Squint and you can discern Pixar’s story—computer-generated imagery transfigured into video for all the world to behold.

The patterns of the exterior walls at Pixar represent pixel shapes.

Pixar’s lobby rivals the atrium of any Hyatt Hotel. It’s a vast open area, its south wall made almost entirely of glass. A commissary, the Luxo Café, is tucked into one side and the tables spill out onto the main floor. The Pixar receptionist calls Torbin Bullock. “He’ll be right out,” she tells Murch.

Murch and his wife, Aggie, first met Bullock as an embryo. While they were living on their houseboat in Sausalito, Aggie was one of the first Lamaze natural birth teachers in the area. Torbin’s mother was in her class. Coincidentally, Torbin’s father, Tom Bullock, was a film editor. Over the years the Bullocks and the Murches, along with their kids, crossed paths at social functions and film events. Torbin and Walter’s daughter, Beatrice, are good friends.

Torbin Bullock, an editor at Pixar.

Murch and Bullock collect their pasta from the Luxo Café and go sit at an outside table. Torbin, in his early 30s, is husky and Nordic-looking, with short, cropped blond hair.

“You want to cut Cold Mountain in Final Cut Pro?” asks Torbin, incredulously. “In Romania?” He pauses, dramatically. “Are you out of your mind?”

Before this get-together Murch reached out to Bullock by phone. “Walter told me, ‘We’re thinking about using Final Cut Pro on Anthony’s next picture. What can you tell me about it—good things, bad things.’ I thought he was crazy—or should I say, a braver man than I am. Especially since Final Cut Pro 3 had only just come out and hadn’t really been put through the wringer.”

After having worked on a number of studio and independent films in the Bay Area, Bullock started working at Pixar in 1995 as second assistant editor on Toy Story. By 2003 he was promoted to associate editor on Cars. In high school Torbin worked in his father’s studio, synching up dailies and conforming sound tracks. He tried to imagine another path, spent a few years in college at San Francisco City College and at SUNY Purchase, but just couldn’t shake his genealogically stamped future. He was a “film kid,” as he puts it, like an Army offspring who refers to himself as an Army brat. And like other Bay Area film kids, Torbin attended “the Droid Olympics,” annual film parties at Murch’s Blackberry Farm. There Murch, Lucas, Tom Bullock, and dozens of other editors, directors, and film crew got together for a day of fun, frolic, and competitive post-production contests, such as the 1,000 foot picture and sound rewind event.

Over lunch, Torbin tells Walter what he’d be concerned about if he, Torbin, were Murch’s assistant. “Make sure you buy the most hot-shit computer you can, make sure you have two of them, load them up with as much RAM as you can, and bring backups of your secondary monitor boards and stuff like that.” He speaks to the issue of networking the computers so they can share media files: “Put together a RAID (redundant array of independent disks) system so if you lose any of your data, or if one of your drives goes bad, and you’re in the middle of fucking nowhere, at least you can yank that drive out, hot-swap it, and shove in a new one that rebuilds the system on the fly. That’s the way you want to be in feature-land.” A feature film in post production should never grind to a halt because the equipment goes down.

The Droid Olympics were held for many years at Murch’s house.

The “Stacking Film Boxes In Order” event.

Murch celebrates on winning film box stacking.

Art Repola competes in the “1000 Foot Rewind Race.”

Not having actually worked for Murch but knowing him outside the film world his whole life, Bullock is in a good position to make observations. “Walter does his research, but once he makes up his mind, he goes for it. I think he made up his mind when he first spoke to me. He just wanted to see if I could talk him out of it. Walter wanted someone to come up with a reason not to use Final Cut Pro. And really the only reason not to was a question of courage and a question of making sure everyone knew it was going to be a work-in-progress.”

Murch and Bullock talk mostly about Final Cut’s problems from an assistant’s point of view. There are four big concerns, as Torbin describes them to Murch:

1. Rendering time for effects—the length of time it will take the machine to permanently digest an effect, like a dissolve or fade, and save it into a cut.

2. Media management for large amounts of digitized material: how to organize it and have it be easily and quickly accessible. His understated, prescient observation: “To get into these issues with third-party cards can be messy.”

3. Having multiple users on multiple computers. Bullock says that up to now “sneaker net” has been the only reliable networking solution for FCP—that is, walking external hard drives around from one station to another.

4. In general things are “a little flaky in Final Cut Pro 3,” as Torbin puts it. “Sometimes footage just disappears”—which Ramy Katrib had also told Murch.

But the biggest concern for Torbin is Final Cut Pro’s change list functions. “The rest of it,” he says, “like the hardware issues, we can get around. Give it enough money and you can set up your infrastructure so risk is at a manageable level—down to 10 percent, which is just as good as anything else, including Avid. But the change list is a serious issue.”

Murch is fully aware from his discussions with DigitalFilm Tree that the edit decision list (or “cut list”) function in Final Cut Pro 3 is untested for a film with the volume of footage he expects in Cold Mountain. And there is no change list function at all. “I warned him about the cut list factor,” Bullock says later. “No one had really run that much footage through. There was no way to know when it would fall apart. In theory it could handle any number of files, but even Avid has its upper limit. But Walter continually invites trouble. It isn’t that after 20 years he’ll just decide to try something different. It’s like his move to use flatbed editing tables from the old upright Moviola. He’s tried all the new editing systems that came along, because they were better or worse, not because they were simply different. He’s interested in new ways of technology. He gets bored. I’m convinced he gets bored. That’s why he willingly puts himself into positions of challenge.”

As their lunch at Pixar wound down, Robert Grahamjones comes outside to join Murch and Bullock. Murch warmly greets his former assistant on The English Patient and The Unbearable Lightness of Being. Like many others in this field, Robert, a sturdy, bantam-sized man with a ready laugh, gravitated to film from photography. One of his first film jobs was working as a driver on the locally produced animated feature, The Plague Dogs. In addition to shuttling animation cells from studio to lab and back, Robert took director Martin Rosen to and from the sound mix at the Zaentz Film Center in Berkeley.

It wasn’t long before Grahamjones made contacts that led to apprentice editing on two of director Rob Nilsson’s locally made independent films, On The Edge and Signal 7. Soon Bay Area film editors were keeping Grahamjones busy working as an assistant. His first contact with Murch occurred in 1985 on George Lucas’s $20 million Michael Jackson video, Captain Eo, directed by Francis Coppola, that was installed at Disneyland. Grahamjones was already on the project when Murch came in to help Lucas finish the project, which stretched out well beyond its original budget and schedule. From there Murch hired Robert to be a film assistant on his next feature, The Unbearable Lightness of Being, directed by another Bay Area director, Philip Kaufman.

Robert Grahamjones, an editor at Pixar and Murch’s former assistant on Unbearable Lightness of Being and The English Patient.

After lunch Robert leads Walter down the dimly lit halls at Pixar to his windowless edit room. The former assistant, now host to his mentor, will give Murch his first demonstration of Final Cut Pro. It’s as if the master bricklayer on that Pixar building turned to his hod carrier for a better method of laying bricks.

“I was surprised when we started going through things,” Robert says later. “He hadn’t touched Final Cut before—he really didn’t know how to move this thing to there, how to make a cut. He hadn’t messed with the machine. He was about to embark on Cold Mountain and he hadn’t really used it!”

Murch heard about Final Cut Pro systems issues from Torbin Bullock. Now he was interested in learning interface and editing gestalt from Grahamjones, who straddles the film/video/digital worlds and knows Walter’s way of working. They share a special relationship, not unlike firemen in an engine company. The intense experience of working together on a major film is deep and mutually dependent. Robert could talk Walter’s language, using the kind of shorthand an assistant and an editor come to rely on.

Each editor uses an identical system differently, just as novelists will use word processing software in their own ways. A good tool is adaptable. The Final Cut Pro system is flexible, allowing the same task to be performed in a multitude of ways. This is one of its attractions to Murch, who is all about customizing his tools and work environment to fit his style.

“He’s had an Apple computer forever,” Grahamjones says later, “and he loves doing things on it. The prospect of being able to cut a film on his own desktop computer just really kind of tipped it. He was willing to go into unknown territory just for that fact alone. As far back as 1986, on Unbearable, we did lots of database things on FileMaker using Mac SEs. If Final Cut had been, say, a program only available on the PC platform, it wouldn’t have got his attention.”

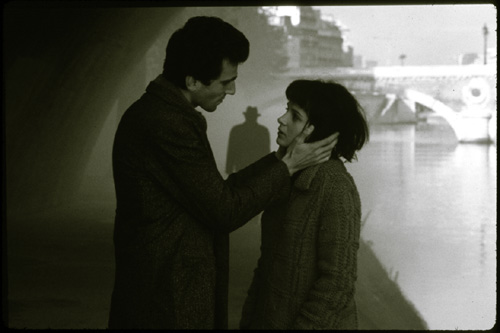

Going to work for Murch on The Unbearable Lightness of Being meant Grahamjones was pulled into all sorts of experiments with editing equipment and work flow. Unbearable was the first time Murch used his custom-made picture boards, for example; an alternate way of seeing the film in progress through still photos pasted onto large black foamcore boards. It’s a system he’s used on every film since, including Cold Mountain. Murch selects from one to eight representative frames from every set-up—“defining moments,” he calls them—that best represent the “story” of that particular shot, emotionally or visually. On Unbearable Grahamjones used a copy stand mounted with a 35mm single lens reflex camera to photograph each frame of film that Walter marked. Mounted side by side, in story order (or, as the story was written in the screenplay) these postcards from the movie create an imagistic, dream-like pattern. Walter uses the picture boards because it lets his eyes dance through the film and discover hidden patterns and rhythms, new ways of relating to the material. For Unbearable there were 4,000 stills and 40 boards to hold them. With computer-based digital editing Walter’s picture board images are captured with a keystroke—a screen shot.

Grahamjones recalls that day at Pixar. “A lot of what he was coming to me for wasn’t the specifics of how to press button A, B, C, or D—mainly what he was looking for was to make sure it was flexible enough for him because he doesn’t want to get into a situation where there’s only one way to do certain things.”

Grahamjones shows Murch how Final Cut allows editors to cut sound in “sub-frames,” or fractions of film frames. A 35mm film frame equals 1/24 of a second running at normal projection speed. On an Avid system at that time, soundtracks could only be cut right on the frame line. So, an editor gets stuck working in 1/24 second chunks. (When sound editors work in their native software programs, such as ProTools, they have much more latitude.) This may seem adequate, but a frame is a large block of time in the film continuum. For a breath, a beat of music, or a sound effect to be heard exactly where the Avid editor feels it belongs, he must build in tiny fades or dissolves to create the equivalent of sub-frame edits—again, a time-consuming process. “That was one of the exciting things to him,” Grahamjones reports later. “He said, ‘Oh, sub-frames! I like that!’”

After three hours, Murch finishes his session with Grahamjones. “It was fairly inconclusive,” as Grahamjones describes it. But Murch didn’t come to Pixar to decide whether to sign on for Final Cut Pro. He was looking for reasons not to go forward. Murch saw the system’s ergonomics, the way it cuts footage, and that seems to work well for him. “The big unknown,” according to Grahamjones, “was how it was going to mesh into a system overall because the way I’m using it, I told him, I can’t help with that. That’s going to be the make or break thing. But he left feeling very Walter-like, I think. Mission accomplished.”

From The Unbearable Lightness of Being with Juliette Binoche and Daniel Day-Lewis.

Indeed there was still much to be figured out—issues Grahamjones didn’t have to manage in his own work, since he was cutting projects that were shorter than full-length features, without a huge volume of film dailies. Also, the end product for most of what Grahamjones worked on was videotape, not 35mm film. Final Cut was designed to work properly in video and had already been used extensively on commercials, documentaries, and major television shows. Could the application be nudged into the spotlight of big-time feature films before Apple’s design team believed it to be ready? Murch first considered using Final Cut Pro instead of Avid on Cold Mountain because the Apple system offered him economies of scale—more workstations at less cost. Some consequences of that choice appear to promise more elegant ways of working, like editing sound in sub-frames. But choosing Final Cut for such a big project may also cause difficulties and lead to troubling work-arounds to handle so much media, get reliable cut lists, and transfer sound editing information.

Nearly six hours after finishing their lunch together, Murch walks into Torbin Bullock’s edit room. “What are you still doing here, Walter?”

Mix Magazine’s 20th Anniversary’s edition with an excerpt of the article written by Walter Murch.

“Is there any way we can look up something on the Internet and also check my email?” Walter asks.

“Sure,” Bullock says, “but I’ve got to go then, Walter. You kinda came in on my ticket, and I can’t just leave you here by yourself if I’m not here!”

Murch quickly checks his email and researches an item for the Mix magazine article. Then he and Bullock walk out to the Pixar parking lot and say their good-byes.

June 6, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Finish the article for Mix at 2am, send it off to Tom. It is a couple hundred words too long.

After visiting Bullock and Grahamjones at Pixar, Walter spends time the following week reading the Cold Mountain script and making his notes for Minghella.

June 8, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Finishing Cold Mountain. Whole middle section very moving. Harder at the beginning, like the book but in a different way. Tear sting a couple of times, around the murder of Esco, Maddy, etc. I wonder how it will end. A swallow: trapped (how?) in the east part of the office, flying around, chirping. I raise the blind, open the window, and it circles seven times and then, lowering its spiral, flies out to freedom. My heart leaps. Thank you.

This won’t be the only time Murch deals with a trapped bird in the course of Cold Mountain. It’s one of those synchronicities that seem to insinuate themselves in and around Walter—one month hence Anthony Minghella will deliver a final version of the Cold Mountain screenplay, this one dated July 9, 2002, and marked, Shooting Script *Revised.* It contains a new scene, number 18, which is entirely without dialogue:

INT. CHAPEL, COLD MOUNTAIN TOWN. DAY. SPRING 1861

A BIRD IS CAUGHT INSIDE THE NEWLY COMPLETED CHAPEL.

It flies in short, terrified bursts, hitting windows.

Ada is there, then Inman enters. Gradually she and

Inman close in one the bird; Inman removing his coat

to use as a net.

There is still a lot Murch must do in terms of making the decision to use Final Cut Pro as his editing system. And he hasn’t even tried the system yet with his own hands. Although Steve Jobs indicated support for Murch in that earlier email, Murch’s working relationship with Apple and its Final Cut Pro development and support teams is still up in the air. At this time the Cold Mountain producers and studio people handling budgeting and logistics are not even aware Murch is thinking of alternatives to the Avid system they assume he will use. Murch does not want to broach the subject until he is sure he himself wants to make that change. And then he will do so only when he has answers about cost savings, creative benefits, and workflow effects on the other film departments. Meanwhile, Ramy and DigitalFilm Tree are feeding Murch results of their ongoing research and investigation of FCP. They’re also preparing a list of help items Murch and Cullen will ask from Apple at the upcoming meeting in Berkeley.

What did Minghella think about Murch using Final Cut Pro as his new editing system? Many months later Minghella summarizes his attitude: “I have such trust in Walter that if he’d said he was going to cut the film on an adapted bicycle, I would say, well, okay. Because I would just rely on him to understand the implications.”

June 10, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Talked to Ramy K: Things are boiling. Some at Apple are with us, some are not—they are working on FCP 4, and this would take effort away. Ramy working on a short list of fundamental issues, drawbacks, which are keeping FCP from being all it could be. Foot draggers at Apple are people facing immediate reality, but this (CM) is bigger than all of them, says Ramy. OMF is a moving target right now, Brooks one of the designers, could fix everything in a week if the API [application programming interface] is there. If it isn’t, it could take three months. He was very happy to hear about Brad and Iron Giant pushing Steve J. from the Pixar angle. “That’s it then, it’s a done deal,” said Ramy. I had the idea of bringing TC and LS to the meeting on the 18th if they are available, God willing.

Ramy and Sean continue talking nearly every day about systems and technical concerns even while Sean is on vacation with his family in Germany and Italy. The drive toward making the technical decision about using FCP continues at full speed but Walter needs to spend more time with mouse in hand to be comfortable with it creatively. For that he goes to the “home office”—the Saul Zaentz Film Center in West Berkeley, where Murch spent much of the previous 15 years film editing and sound mixing. This is where he just finished mixing sound for K-19: The Widowmaker, where he edited and mixed The Talented Mr. Ripley, The English Patient, and The Unbearable Lightness of Being, and prepared the re-cut of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil.

When Saul Zaentz took over Fantasy Records in 1967, it was a small, quirky San Francisco jazz label with artists such as Dave Brubeck, Cal Tjader, Mongo Santamaria, and satirist Lenny Bruce. The company’s catalogue grew to be one of the world’s largest for jazz, rhythm and blues, gospel, and soul after Zaentz and his partners acquired record companies such as Riverside, Contemporary, Prestige, Stax, and Specialty.

The company had a rock-and-roll label, Scorpio, that recorded local bands, including The Golliwogs, four guys with a distinctly down-home sound. Before Fantasy released their first album, the group and its lead singer, John Fogerty, came up with a new name for the band, Creedence Clearwater Revival. They blew the roof off the place. Zaentz soon got involved with motion pictures, helping to produce Payday (as executive producer without screen credit). Released in 1972, starring Rip Torn, it didn’t go too far. But a few years later, with Michael Douglas, Zaentz produced One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and he had a hit the second time out.

Being committed now to producing more films, and also being a good businessman, Zaentz expanded his post-production editing and sound-mixing facility. The two-story offices grew into a seven-story building, still the tallest in that part of Berkeley. Its preformed concrete walls embedded with river rocks house the Zaentz Film Center, the record company, and state-of-the-art recording studios. When the Film Center isn’t being used for Zaentz’s own films, like The Unbearable Lightness of Being, The Mosquito Coast, or The English Patient, clients from Hollywood make the trip north to work in the center and use its talented band of sound editors, engineers, and mixers.

The Fantasy Building in Berkeley, California, location of the Saul Zaentz Film Center.

Saul Zaentz, film producer and winner of Best Picture Oscar awards for The English Patient, Amadeus, and One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.

It is appropriate for Murch to come back to the Film Center for his first test drive on Final Cut. Not only had he edited and mixed some great pictures here, he likes the people and the place. And the feelings are mutual. The staff, house editors, mixers, and engineers appreciate Murch and his approach to filmmaking. Michael Kelly, director of special projects at the Film Center, says having Murch working on a project in the Film Center means doing things “way different” from when other film personnel come in to use the place.

“If he decides he wants to figure out problems or a process, you’re in for it, because he’s going to ultimately figure it out at philosophical and subatomic levels. With Walter, if you can’t answer his questions, you’ll end up questioning your own assumptions—discover the limits of your own understanding. He doesn’t do this to get at you but to find the boundaries of logic around systems. It’s Socratic. In small or large ways the Film Center changes the way we do our work because Walter finds better ways to do things. New functions are discovered. They get adapted permanently—or at least temporarily, to appease him.”

Actor Rip Torn in Payday, the first motion picture Saul Zaentz produced.

Jack Nicholsen in One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, produced by Saul Zaentz and Michael Douglas.

The third floor at the Saul Zaentz Film Center, where Walter Murch frequently works.

One week after visiting Grahamjones and Bullock at Pixar, Murch goes to Berkeley to see Tom Christopher, a sandy-haired film editor in his late 40s with the agile bearing of a shortstop. Christopher began in post production as an MRO—machine room operator—at Coppola’s Zoetrope facility in San Francisco. He first worked there in 1980, on Dragonslayer, the film co-written and directed by Murch’s college friend, Matthew Robbins. Murch also mixed Dragonslayer. Being comfortable with computers and high technology, Christopher found himself in more demand as editing and mixing began to move toward digitally based systems. “Walter and I have been talking about non-linear editing—forever.” Indeed, Christopher gave Murch his first introduction to EditDroid, the laser disc-based non-linear editing system that George Lucas developed in 1984.

“Walter was here in the Film Center in the spring of 2002,” recounts Christopher. “It was in the kitchen on the third floor, during a mix break on K-19. I mentioned I was looking into this new Final Cut Pro software. I had already used Adobe Premiere on a few projects. I told him I was very impressed with Final Cut Pro, and he went, ‘Ahhh.’ That registered with him.” Murch asked Christopher for his contact information. Not long afterward an acquaintance of Murch’s was looking for someone to edit a PBS special on local restaurant owner and celebrity chef Alice Waters. Murch referred Tom Christopher, he got the job, and the program became the first American Masters show edited on Apple’s Final Cut Pro.

Murch later called Christopher about the FCP lab of sorts he had going at the Film Center. “We were very hot on it at that point,” Christopher says later, “and we were hearing from other editors, ‘Yeah, yeah it’s an interesting toy.’ But we were seeing it differently; it wasn’t a toy. I had a think tank up here, had the Apple people up here, along with other editors, and had roundtable discussions and talked with the Apple Development Team about what our needs were and how we wanted to use this new technology.”

“I received a call in June 2002 from Walter saying he was very interested in using FCP as his next platform. He had worked out a plan and he had contacted Apple and he wanted to have a meeting up here with me and go over what I was doing. I set up the room so we could have a little platform for him to get warmed up on. What was evident that day Walter came in by himself was he hadn’t really mastered the software at all. But the fact it was new to him didn’t matter.”

“You sit down in front of one of these machines and you’re clueless for the first few minutes, an hour, even days, because you’ve just come off something else, a different editing system. You have to get in the zone. I had Final Cut set up the way I liked to work: the video monitor in the center, and two computer monitors flanking left and right. Walter took charge, as he is wont to do, starting to sculpt the digital environment so it was the way he wanted it to be. Walter got into the zone pretty quick. He started to adjust things. For example, he reset the parameters of the trim window—changing the default parameters.”

“It was a couple of hours and then he wanted to just work on his own. I left him alone, backed off, checked in with him every once in a while. He was fine. He got as far as he wanted and then he took off.”

June 13, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Good session with TC on FCP. Made me nervous about changing “instruments” but... flushed out some questions but some answers too.

Got windshield fixed on Subaru.

Walter later described the anxiety he felt that day in Room 305 at the Film Center, his old editing room during The English Patient, trying Tom Christopher’s Final Cut Pro edit system. “I had the tiniest whiff of ‘uh-oh.’ I was confronted with the fact that I was going to do it—here it is. I was metabolizing that information. If I were a pianist, it’d be as if I were changing instruments and found the pedals were in a different position on this piano. In the middle of the third movement would I have a wrong reflex—go for the pedal here but find it was now over there?”

So far so good. None of the editors he met with—Bullock, Grahamjones, and Christopher—are giving him a make-or-break reason not to use Final Cut Pro on Cold Mountain. While Sean and DFT are finding handholds for systems and workflow issues such as change lists and EDLs, networking workstations, integrating audio files with ProTools, and managing the high volume of film material, Walter is getting more accustomed to the interface, keyboard, and functionality of Final Cut Pro. In ten days Murch will leave for Europe.

June 15, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Timing the script: It took me three hours to get to 1/5th—so it will take fifteen hours total. At any rate, I timed the first fifth, and the mpp [minutes per page] is 1.66, which makes for a total over three hours: 3.06 fast, 3.20 slow. I wonder what it will work out to be in the end?

[WM’s later insert here: It was 2.52 fast, 3.10 slow.]

Didn’t finish timing today—takes about 12 hours to do it (timing each scene twice)—will finish tomorrow

Dan Fort helped create the Cinema Tools application used with Final Cut Pro for film editing.

The meeting in Berkeley with Hudson and Meaney of Apple is three days away. Sean Cullen returns from vacation, giving him and Murch just enough time to make a one-day trip to Los Angeles on Monday, June 17, for their final visit to DigitalFilm Tree. Cullen prepares a background document for the session at DFT—a two-page description of the workflow he plans to use on Cold Mountain to prepare dailies every morning during production. Based on how he works using the Avid editing system, it’s a step-by-step process that begins with receiving just-printed film rolls from the lab and ends with digitized media on Walter’s desktop ready to edit. In his introduction to the document Sean writes, “There are a number of workarounds that I have to use to trick the Avid into behaving...” which are so extensive he leaves them out, for brevity’s sake.

John Taylor, film editor and one of the DigitalFilm Tree’s stable of experts.

When Sean and Walter sit down in DFT’s training room the following day, they learn more perhaps than they ever wanted to know about the kinds of workarounds Final Cut Pro would soon be demanding from them. They each sit at one of the ten Final Cut Pro stations outfitted with Cinema Display monitors normally occupied by pupils of DFT’s Final Cut Pro training classes. Beside Ramy Katrib, the others are chief technology officer, Tim Serda, who will be responsible for integrating and testing the Cold Mountain editing systems; managers Henry Santos and Edvin Mehrabyan; trainer and then DFT president, Walt Shires, FCP and Cinema Tools editor/consultant Dan Fort; and DFT editor John Taylor, who is especially versed in the differences and similarities between the Avid and FCP systems. Serda and Shires are from the original Final Cut team when it was being developed at Macromedia, before the program was sold to Apple. So for Murch and Cullen, sitting in this room with some of the editing system’s original planners and designers is an opportunity to range freely through Final Cut’s nervous system. Similarly, Dan Fort was influential in the development of Cinema Tools—the additional application that allowed FCP to be used for film editing.

The initial discussion is about logging footage in Final Cut Pro: film measurement (feet and frames) versus video measurement (timecode). Timecode is the electronic indexing system used in video that encodes unique time stamps on every frame using a system of hours, minutes, seconds, and frames (30 per second). It is video’s equivalent of key code numbers used on film. Cold Mountain will live in both video and film worlds, so they want to have an easy way to convert between the two logging systems. And while Cinema Tools is the basis for translating the film numbering database to video timecode, and back again, there are process issues about when to convert timecode material into feet and frames, and how to track both. This is Sean’s primary area of responsibility, so Walter stays quiet for the most part, injecting questions occasionally. The conversation is brisk, focused, and serious.

Apropos the topic at hand, Ramy mentions that Star Trek, the television show, had just sent its entire post-production team, including all the editors, to DFT to learn Final Cut Pro. “Walt was training all nine of them,” Ramy says, “until this ‘bug’ came up about 24 frame film versus 30 frame video.” Star Trek uses many short bits of visual effects that originate in film, so conversion from feet/frames into timecode requires a labor-intensive, cumbersome, manual data-entry process for the assistant editors. “Because of this ‘bug,’ Star Trek didn’t go with FCP,” Ramy says, “and we reported to Apple because they wanted to know why it didn’t happen.”

Walter breaks in to ask if Apple’s Final Cut Pro managers are up to date on the problem—a window into the computer company’s sensitivities to entertainment industry needs.

“To the extent they understand anything about 24 frame,” Ramy says sardonically. “They’ve never worked on a film project. See, 99 percent of FCP users aren’t affected by something like this. It’s such an infinitesimal thing. But it could be addressed in an afternoon if they [Apple] have the will to do it.”

Murch is all too familiar with the film business being a tiny drop of economic demand as far as major manufacturers and suppliers are concerned. “We have needs for very fine tolerances in equipment and gear, but the capital base is tiny compared to medical products or ski equipment,” he says.

Walt Shires believes Murch’s involvement will trigger changes to Final Cut Pro, based simply on his status in the movie business. Murch tells the group about his emails to and from Steve Jobs—that his friend Brad Bird, a film director at Pixar, is also contacting Jobs. “I think there is some heat on solving some of these problems,” Walter tells the group.

The discussion continues. Sean is informed that when he first opens a newly digitized clip from film dailies, he should expect to find the timecode numbers to always be wrong.

“Always?” Murch asks. “Good. A reliable bug—that’s much better.”

“This is a rock-solid bug!” Ramy says, to much laughter.

The discussion continues about another sticking point: there is no counter built into Final Cut Pro for keeping track of elapsed time in feet and frames. In Avid it’s a simple toggle to reset the counter from feet and frames, to timecode. “But Final Cut will only count timecode,” John Taylor says. “Sean will have to maintain two separate databases in his log book: one for negative key codes and the other for workprint ink numbers.”

Dan Fort volunteers he could write a filter, or mini-program that would do that conversion for Sean.

“It would be easy for Apple to write something and decode feet and frames,” Walt says, “but it is a matter of this being a very niche-y toolset for someone like Apple.”

Fort also points out such a workaround would have to operate on OS 9.

“Then you’re going to run into the fact that Steve [Jobs] officially pronounced OS 9 dead,” Shires says. “No work or budgets will be spent on OS 9.”

Later, after lunch, the group reconvenes in one of DFT’s small edit rooms where Sean starts putting Final Cut Pro through its paces. He asks if the font size on the interface can be enlarged since Murch edits standing up, is farther from the screen, and needs larger type.

“No!” someone says, mockingly, a dig at intransigent software designers. But of course it can.

“I suppose you want to remap the keys, too?” John asks rhetorically, referring to editors who like to customize their keyboards for frequent shortcuts. This joke isn’t so funny.

“Yeah, I know,” Sean says dejectedly, without prompting. He’s already aware keyboard remapping, a function native to Avid, is unavailable in FCP 3.

Finally Walter sits down at the keyboard. With everyone quietly observing, like an expectant audience awaiting the first chord at a piano recital, Murch tries out some basic functions and edits on Final Cut Pro. This is not a trivial moment. The group, which is quickly becoming the FCP/Cold Mountain support team, feels the gravity.

At the end of their day together, Ramy sets up a conference call for Sean and Walter with Brooks Harris to talk about the thorny problem of getting sound files from Final Cut into ProTools. At the heart of this is FCP’s inability to provide OMF compositions (edited audio information) that can be emailed to the sound department and then re-linked to their raw audio files. FCP can only provide OMF export with audio embedded—that is, carrying the sound media with it. Normally that may seem convenient, but sound editors need to work with raw audio files of the highest quality. For Cold Mountain Murch wants the sound to be delivered at 24 bits. The higher the number, the more precisely the original audio signal will be reproduced. (Standard CDs use a bit rate of 16.) However, Final Cut Pro can only handle sound files with 16-bit sound information. Using embedded sound exported from FCP will compromise the quality of sound that was originally recorded at 24 bits.

The other problem with embedded sound information is that Murch wants to be able to send the sound editors his blueprints for the building (edits points where his cuts occur, levels, equalization, etc.), not the bricks, mortar, lumber, and drywall—all the building materials—which is clumsy, inefficient, and unnecessary. So, if Brooks Harris, one of the original developers of OMF who helped develop OMF Tool Kit, an application used by the post-production community, can circumvent these hurdles, all the better for Murch, Cullen, and the sound editors on Cold Mountain. Everyone stands around the speakerphone in Ramy’s smallish office. On the wall is a full-size Bebe fashion poster featuring a model in her underwear. Two years later, it will be replaced by a one-sheet of Cold Mountain.

“Walter and Sean are meeting with Apple tomorrow,” Ramy tells Harris, “so everything’s coming to a head. This sound problem—not being able to transfer composition-only sound from FCP—is one of the top three issues that’s on the table right now.”

“If they just gave me access to the API,” Harris responds, “I could do it through OMF.” There is more discussion about details and options. But in the end, a solution seems possible, and from a top programmer that DigitalFilm Tree knows and trusts.

“That was encouraging,” Ramy says after the call is finished.

“Yeah,” Sean says cheerfully, “and Brooks seems to be a pretty pessimistic individual.”

JUNE 18, 2002—BERKELEY

Walter and Sean arrive at the Fantasy building in West Berkeley for their meeting with Apple Final Cut Pro managers, Brian Meaney and Bill Hudson. They convene in Murch’s old editing room, No. 305, with Tom Christopher—who is hosting the get-together—and his assistant editor, Tim Fox. Sound editor and sound supervisor Larry Schalit, with whom Murch had worked on The Talented Mr. Ripley and K-19 is also there. Schalit will contribute to the issue of sound file transferability between Final Cut Pro and the ProTools application. Christopher has spent considerable time with both Meaney and Hudson on previous occasions as a beta tester for FCP.

“Coming into the Apple meeting,” as Sean later described it, “all of the momentum was towards Final Cut Pro. I had essentially decided that Final Cut Pro was the way to go. The only question was the best way to approach it. My sense at the time was that Walter hadn’t decided—that he was still kind of like, ‘Hmm.’ But I certainly had decided, and DigitalFilm Tree had decided, that they really wanted this to happen.”

As Tom Christopher points out, the meeting is a natural outgrowth of Apple’s aggressive marketing campaign of Final Cut Pro to the film industry: “A two-page, full-color spread on FCP in film trade magazines? That little flip of a page sent out a message. And this meeting between Walter and the Final Cut development team is the culmination. When you advertise in Variety you’re not attracting the high school drama market, you’re not going for industrial clients, you’re going after movie people. And here you have a movie person, and he wants to do it now.”

Two years later, also looking back on that Berkeley meeting, Bill Hudson, Apple’s senior manager of Market Development and Strategic Accounts for Professional Applications, says, “We wanted to make sure someone of Murch’s experience understood what the workflow was going to be—making sure there were no blind spots. If you go into something with your eyes wide open and you know what to expect, you can address things as they come up.”

In the corner room on the third floor of the Zaentz Film Center, Sean Cullen presents his Cold Mountain game plan to Hudson and Meaney, what systems he plans to use, and how he will put together the edit room. Cullen presents several unresolved issues based on his research during the last several weeks. He proposes that Apple help solve them.

“They were basically giving a brain dump of post-production needs for this project,” Christopher recalls. “The wants, the wish list. It was the most elaborate Final Cut Pro scheme probably ever devised.” Hudson and Meaney listen quietly. Cullen does not get much of a response.

In essence, Murch and Cullen are asking Apple for Final Cut Pro functions and attributes that are not likely to be available until the next version release. Christopher, having been in many development sessions like this with Apple, knows this is a line that cannot be crossed. Christopher tells Cullen that Apple is being non-responsive because neither Cullen nor Murch have a non-disclosure agreement with Apple.

“Hudson turned to me,” Christopher recalls, “and said, ‘Thank you.’ Because these are the rules they run by. You have to talk about what things are important for your workflow. You’re not allowed to come around and say, ‘When can I have it? Will it be part of the next release?’ You can’t buttonhole these guys, because they’re not allowed to talk like that. But they do take the information you give them; they take that home.”

First off, Hudson and Meaney feel Sean will have problems getting the FileMaker database program to work with FCP. Cullen says, “Everything I’ve seen shows me that it’s just the same as using it to work on an Avid, so that’s not a problem. I’m expecting to have to do that kind of work.”

Sean is warned that FCP might crash.

“I’m expecting to have crashes. Crashes happen all the time. That’s not a problem.”

“Media might get corrupted.”

“Media gets corrupted all the time. I’ve got videotapes.”

Apple does not seem to understand the amount of strategic thinking Sean, Walter, and DigitalFilm Tree have already done on their own. Sean also senses they hold Avid in too much regard. “I think they had an impression that the Avid was much more turnkey than it was. Their impression of Avid was the sort of big brother—that it can’t do anything wrong, that Avid’s perfect.”

Brian Meaney, part of Apple’s Final Cut Pro team.

“Up until that point,” Brian Meaney explains later, “many of the people we had met in the higher end of the film community, with studio productions, didn’t understand Final Cut Pro and its nuances—didn’t understand its differences from the Avid or other systems that they may be used to working on—at a tech level as well as the editing itself, to some degree.”

Then the issue of systems versions that Walt Shires alluded to at DFT the day before in Los Angeles comes up. Bill Hudson says the Final Cut Pro team has been instructed from the highest levels at Apple that all advancements, all software development must be in OS X. According to Tom Christopher, “He was basically saying, ‘None of this can happen for you, Walter, Sean. You’re in 9.2.2. You can’t have any of this. We can’t do this for you. We are doing things that you will like, but those things will only be usable in OS X.’ That was a sobering moment. I wouldn’t call it chilling, because it didn’t chill these guys. But it basically set the stage for this being a space walk with no leash. If you’re on the Shuttle and you go out to fix something, you have a leash. The astronauts have a leash. Bill basically said you’re going to be a space walk with no leash, no net, walking out with no net.”

While understanding the partnering relationship Sean and Walter would like to have with Apple, Meaney implies that FCP is still fundamentally a consumer application, not intended—not yet, anyway—to withstand the demands of a full-length feature film of Cold Mountain’s magnitude. He intimates there are reasons, technical things, that Walter and Sean don’t know about that could hurt them.

“Brian Meaney is a really good technical Apple product manager kind of guy,” Tom Christopher says later. “I’ve been at trade shows with him. He has this rocket delivery of stuff. Very confident. Here, the nervousness level was quite high. He was getting more intense at this meeting. I could just see he was nervous.”

“We knew for a fact that OS X wouldn’t work,” Sean recalls, “because DigitalFilm Tree identified a number of problems with it.” Cold Mountain would be using a SAN (shared area network) because Sean and Walter will network together four or more computer stations that share audio and video from one central storage data bank via a fiber channel. No SAN solutions run on OS X, either from Apple or any third-party company. Another problem with OS X is that Aurora, a third-party hardware developer for Apple, has not completed a capture card driver to use with OS X. Aurora’s Igniter card, which DFT will include in Murch’s system, is the most reliable and proven method to capture 29.97 frame per second (fps) video dailies to 24 fps video in FCP and provide 29.97 output and viewing, all in real time. Finally, at this time OS X is an unknown quantity in general.

For Cullen, System 9 versus OS X was a red herring: “We said to Apple, ‘We’re going to do it on Final Cut Pro, and that’s what matters. We don’t care about System 9 or X. We can switch over to OS X later in post production.’” The push for OS X, which Meaney and Hudson admit comes from “top management,” has to do with Apple’s mission to eliminate OS 9 from the scene. When a major computer maker like Apple introduces a new system version, it wants it to become the gold standard as quickly as possible. But software upgrades are not like launching the Euro and simultaneously taking all the old European currencies out of circulation. To this day in fact, OS 9 is still used to run most advanced Final Cut Pro systems because of the lack of third-party software and hardware development for OS X.

“We hadn’t come across anyone yet,” Brian Meaney says later, “who has spent the time to understand these things. What we don’t want, and what we worked very hard to do, was to not have false expectations out there in the industry. Many times that means not going in to make lots and lots of sales, and we’re fine with that and always have been. We had reservations that this might not be a good idea.”

“They were very much between a rock and a hard place,” Sean recalls, speaking of Hudson and Meaney. “I can certainly understand their concern and their trepidation. Myself and DigitalFilm Tree, we had already decided we would be able to make it work. It was a question now of how much would Apple help. How much easier will they make it? Before the Apple meeting I said to DigitalFilm Tree, ‘It’s important that we have a solution that gets us all the way through post production to the delivery of the film that will be successful if Apple goes out of business tomorrow, because we can’t tie the fate of this film to the fate of a software company. Apple came a little too late to block the flood.”

“They really were saying, ‘We don’t want you to do it, because we’re not ready,’” Cullen recalls later. “I could hear a little corporate doublespeak. There was a little bit of, ‘We know what’s going on, but we can’t tell you. We don’t want to share information with you directly. We’ll only share information with you in an indirect manner.’”

The session in Room 305 ends in a stalemate of sorts. Sean and Walter shared their plans to use Final Cut Pro on Cold Mountain and their requests for how Apple might smooth the road. Apple had a punch list of needs and wants to take back to Cupertino from a top feature film editing team that would soon be pushing the limits of its editing software. The atmosphere was cool but not unfriendly. They adjourned for lunch to the Westside Bakery, a light and airy café across the street from the Fantasy building.

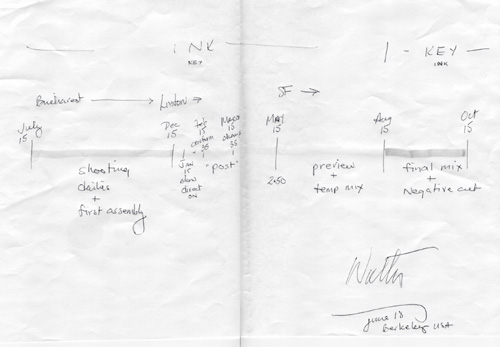

Murch’s sketch of the workflow he planned for Cold Mountain, as drawn during his meeting with Apple in Berkeley.

At lunch the conversation continues about film editing and Final Cut, though less intensely than earlier. Murch excuses himself for the rest room. Tom Christopher turns to Hudson and Meaney, who sit across the table from him. “Walter is very determined and he will figure it out. His crew will make it work. They’re tired of doing it the way everyone else is doing it. You’re not dealing with some guy in a garage on Cahuenga Boulevard in North Hollywood. And you’re not going to dissuade him by saying ‘It’s a scary tunnel you’re going into, Walter.’”

Larry Schalit was also at the lunch and later recalled: “I sensed Walter was very disappointed by the end of the lunch at the Westside. He was disappointed Apple wasn’t going to help him out. Apple could have been enthused, like DFT. They were nice guys, but it seemed they never really got what an opportunity this was and who Walter really is. And they didn’t really give him the respect. Here they were, sitting across from the one guy who could take FCP to the big leagues, to big features. I don’t think they realized that.”

Bill Hudson remembers it differently. “When we were driving back to Cupertino,” he says later, “Brian and I were going like, ‘Okay, wow, he is totally getting it, and he’s seeing the benefit in working a different way.’ Not a lot of people are willing to set aside the tools that they’ve honed their craft on and have the confidence in their craft, and he does. Walter is a great exception. And that was really exciting and invigorating for us.”

But Hudson and Meaney also realized that with OS X eclipsing OS 9, they could not do all they might want to assist Cold Mountain. “We could make improvements,” Meaney continued later, “but any improvements were going to be on System X. And he [Murch] wasn’t going to benefit from those. We don’t do special builds, special fixes, to try and help out individual clients. We do a lot of software for a lot of people. We needed to make that clear. In addition to that, if he hit any particular problem, we weren’t going to be able to help.”

Hudson sighs. “Yeah,” he says, ruefully agreeing with Meaney.

June 18, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Meeting with Apple Bill Hudson and Brian... Larry Schalit, Tom Christopher, Sean, Me, and Tim Fox. All seems good or tending that way. They were greatly relieved to meet us (i.e. Sean) and feel our competency and enthusiasm. We told them about our reservations and they listened to us attentively. Tired... Nice evening with Bea and Kragen and Hana sitting on the sofa.

Soon thereafter Walter asks Ramy to send him a budget comparison between Avid and Final Cut Pro. He will use that information to prepare his final pitch for using Final Cut Pro. Interestingly, Murch puts a positive spin on the meeting with Apple in his email to Minghella and producers Bill Horberg and Iain Smith.

June 20, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Avid system vs. FCP: Avid would cost $62,000 to purchase (edit point). We would need two of them for $124,000. We get four [FCP] stations for $54,000 = $13,500 each. Not much more than what I paid for the Pro Tools stations back in 1998. Wrote FCP letter and list to Ant and Bill and Iain. Godspeed!

Then, on Sunday morning, June 23, after a few days spent wrapping up his affairs, including getting a bad tooth pulled, Walter departs for the San Francisco airport to catch his plane to London where Aggie arrived a few weeks earlier, to care for her ailing mother.

June 24, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Arrive at London, no one from the film to meet me as planned. I took the train in, too much luggage to handle myself, but I did it. Didn’t have any pound coins for the trolley, but the ticket lady gave me change. Then the first trolley I got at Paddington had a wonky front wheel, so I switched to another one which worked fine, then got a cab to Kingstown Street, and there was Aggie!