Chapter 2. Running on the Fault Line

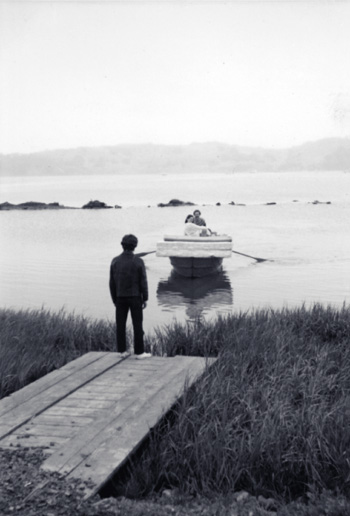

The lagoon near Blackberry Farm.

To this day, if you go to the San Francisco Bay Area and want to find the town where Murch lives, don’t look for a sign. It disappears whenever the Department of Transportation puts one up. Over the last 34 years, 22 signs have been pulled down; the people who live here would rather no one else found it. The community, located north of San Francisco on the coast, is a magical village of Victorian farmhouses and clapboard homes, surrounded by green pastures and redwood forests overlooking the Pacific Ocean. The adjacent lagoon that empties into the ocean forms a moat to the south and east; there is ocean to the west and wild forest to the north. From the beach you can see pale apartment buildings on the hills of San Francisco, only seven miles away as the crow flies. Driving to The City, however, is no easy task—the first half of the trip is over convoluted mountain roads and then, as a bracing contrast to the bucolic drive, you run the gauntlet of a commuter-jammed Golden Gate Bridge. It’s over an hour, one way, on a good day.

The town’s basic mix of farmers, fishermen, and working professionals is peppered with artists, musicians, writers, second-homers, and drop-outs. A few are poor and homeless, and some quite wealthy. With residents bicycling into town to run errands and catch up at the community bulletin board, even a big-city attorney can’t help but want to work at home amid the eucalyptus and clean, salty air. It’s just too idyllic not to.

In 1987, when Director Philip Kaufman needed a closing American locale for The Unbearable Lightness of Being, he chose Blackberry Farm, one of the 19th century farm houses just outside the town. It wasn’t merely a good-luck find by an astute location manager; it happened to be the home of the film’s editor, Walter Murch. He and his wife, Aggie, and their two children, Walter (then 4) and newborn Beatrice, moved here in 1973 from the Sausalito houseboat where they had been living since 1969. With two children, life on the water in relatively cramped conditions no longer seemed like such a good idea. Sisters Connie and Carrie Angland (then aged 10 and 11) came to live permanently with the Murches in 1975.

Walter and Aggie moved from their houseboat to Blackberry Farm in 1973. George Lucas waits on the shore to help.

It just wasn’t in the cards for Walter to move back to Los Angeles where he had gone to graduate film school at the University of Southern California. Other budding sound editors and mixers might find steady work there, at the center of the American film industry, but Murch and his college friends all had something else in mind besides getting good jobs in Hollywood. The group included Francis Ford Coppola (for whom Murch had already done sound work on The Rain People), Carroll Ballard (director of The Black Stallion, Never Cry Wolf, and Fly Away Home), Matthew Robbins and Hal Barwood (Robbins directed and Barwood produced the film Dragonslayer; they were uncredited writers of Close Encounters of the Third Kind); Robert Dalva (film editor on The Black Stallion, Jumanji, Jurassic Park III, and director of The Black Stallion Returns), and George Lucas.

Coppola, Lucas, and Murch and their families moved to the San Francisco Bay Area in the spring of 1969 to complete The Rain People, launch Zoetrope Studios, begin work on THX-1138, and establish an approach to filmmaking independent of Hollywood that was more in keeping with the low-cost, collaborative way they had made films at USC and UCLA. This was well before Lucas’s success with American Graffiti and Star Wars, and with what became Lucasfilm, Skywalker Sound, Industrial Light & Magic, and Pixar. It was prior to Coppola directing The Godfather. And it was six years before Saul Zaentz, the Berkeley-based producer, would win Best Picture and four other major Oscars for One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975). By the late 1970s, Coppola’s vision of a Bay Area network of artists and craftspeople had become reality: a critical mass of filmmaking talent and financing that could flourish outside of Southern California.

Lena Olin as Sabina, at Blackberry Farm, as seen in the motion picture, The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

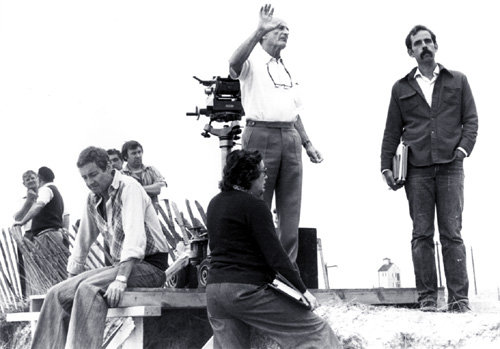

Director Philip Kaufman, left, and Daniel Day-Lewis, center, on the set of The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

Beatrice Murch.

Connie and Carrie Angland.

Walter Slater Murch.

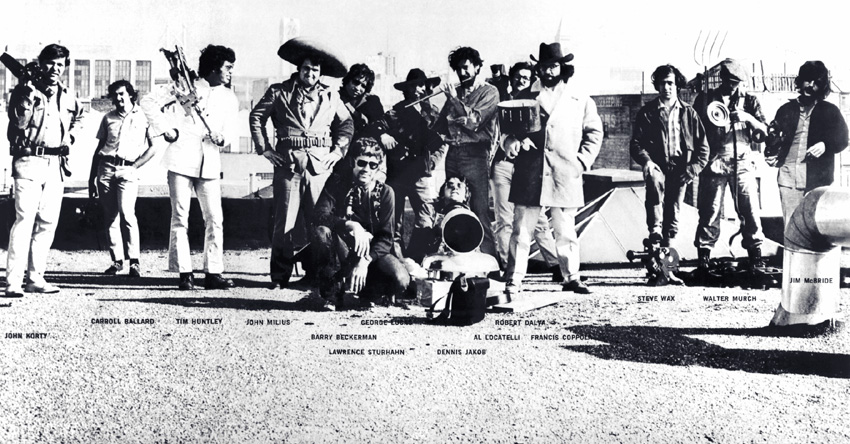

The gang from American Zoetrope in 1969. Walter Murch is second from right. Coppola (fourth from right) holds a zoetrope, invented in 1834. When sequenced photographs are viewed through slits in this device they produce the equivalent of a motion picture. The word “zoetrope” is a combination of Greek words meaning roughly “wheel of Life.”

JUNE 1, 2002—BLACKBERRY FARM

It’s a windy and sunny Saturday. Murch has lived here now for nearly 30 years. To a casual observer, it is another day for pleasant diversions in this Northern California Shangri-la. Surfers in wetsuits find the curl that breaks off the point. Daytrippers drop into the local café for cappuccino. Honeymooners in rental cars drive up Highway 1, not realizing (since there is no sign) they’ve just passed the real deal—a more authentic Mendocino than the town up the coast they’ll sleep in that night.

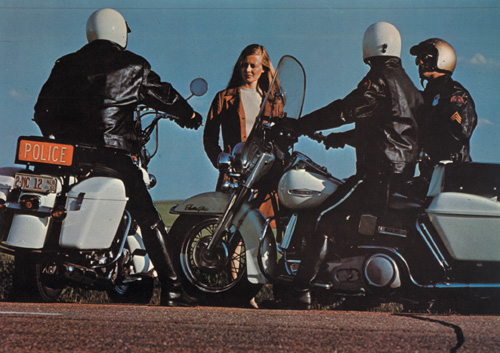

From The Rain People, directed by Francis Ford Coppola, on which Murch did the sound montage and was the rerecording mixer.

Only 27 days ago Murch was in Berkeley at the Zaentz Film Center on the last day of editing and mixing K-19: The Widowmaker, directed by Kathryn Bigelow, starring Harrison Ford and Liam Neeson. As usual, he spent over a year on this single project, and worked consecutive 16- to 18-hour days for the last several weeks to make the release date. So now, with his work done, Walter is prone to what he calls “parade syndrome;” not simply a letdown, it’s a physical sensation. Imagine sitting in the bleachers on Manhattan’s Central Park West, as Walter used to do when he was five, and watch the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade go by. “After the last float, I’d look down at the asphalt,” he says. “It seemed to be oozing in the other direction, left to right. I knew it couldn’t be so, and yet there it was, the result of a reflex motion of my eyeballs. The effect wears off in about five minutes, but while it lasts it is totally fascinating and disorienting to a child. The same kind of thing happens at the end of a film. For a year, I’m used to seeing the film grow, change, evolve, organize, and get more coherent. And then suddenly—very suddenly—it’s done and the film stops changing. But instead of just stopping, there is some mental reflex and the film seems to be disintegrating each time I look at it, leaving me slightly seasick. The film is done, how can it be coming apart? It will take at least six weeks to get my land legs back.”

Despite any queasiness, there is too much to do today to lie low. Walter reviews galley proofs of The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film, the book novelist Michael Ondaatje has written based on discussions about film and film editing he and Murch had over the last year and a half. Murch is also on a deadline to finish an article for Mix magazine on the history of sound in film over the last 25 years.

In three weeks Murch will depart for London and Bucharest to start work on Cold Mountain. For logistical, technical, and artistic reasons, he gets involved right from the start of shooting. Technically, film needs to be processed and printed; oversight and troubleshooting at the lab are the responsibility of the editing team. If things go wrong at this stage—improper processing of exposed film, sound incorrectly synched up with picture, or footage printed and organized incorrectly, for example—it could mean expensive reshooting or losing precious time in the editing schedule for delivering the finished film. Most studio pictures begin shooting with an established release date—for Cold Mountain it’s Christmas 2003—and the studio organizes its marketing and exhibition plans based on that date.

While on location, the editor supervises the preparation of film dailies so the director, director of photography, and other crew members can view the results of their work. Each department head will be given the opportunity to check his or her own work as it appears on film. Sometimes cast members are invited to see “rushes,” as dailies are also called (from being “rushed” through the lab for urgent viewing). The purpose of seeing footage immediately is partly technical: to make sure everything “is there,” in case material needs to be reshot while actors are available and sets are still in place. Also, the director needs to evaluate his own staging and the subtleties of the actors’ performances after the momentary thrill of the take is passed. The cinematographer wants to review his work artistically and confirm that choices of lenses, camera moves, and film stock are appropriate.

The editor begins reviewing footage as soon as it becomes available, logging notes that get incorporated into a massive database in preparation for editing. As soon as enough film has been accumulated—usually after a week or so of shooting—the editor starts to cut the material into scenes and sequences, beginning the lengthy process of assembling film. “The first compilation helps flush out subtle continuity problems that may have snuck under everyone’s radar,” Murch says, “and begins to give the director a sense of how the finished film will look and feel.” Also there is simply a logistical issue of using available time efficiently: if the editor were to begin assembling the material only after shooting was completed—with a backlog of 40 or more hours of film, in the case of a major studio film—it could add months to the editing schedule.

Like all members of a film crew, Murch must be willing to go where the work is. In 1976, this meant editing Julia in London for director Fred Zinneman. Directing Return to Oz involved another two-year stint in London in the mid-1980s. K-19 was shot in Toronto and finished in Los Angeles.

The Cinecittà Studios outside Rome, Italy, where Murch edited The Talented Mr. Ripley.

Murch situates his editing rooms within easy striking distance of the set—but not too close. For example, on The Talented Mr. Ripley, his base was the Cinecittà film studios near Rome, while filming took place at various locations around Rome and Italy. Murch may meet actors on the set, or socially, but he intentionally keeps a certain distance. He will be living with the performers and their characters in his edit room for over a year, and will wind up knowing their onscreen tics and habits perhaps better than they do. Being outside the typhoon of film production not only safeguards Murch from its gale-force winds of emotion, physical exertion, and stress, but it gives him a degree of much-valued objectivity. However, getting ready for a project still means preparing physically, as well as creatively and logistically. Going 8,000 miles from home to work in a former Soviet-controlled state will make it more of a challenge for Murch to do things the way he likes, and put him far from the support systems of familiar film labs and edit facilities. It also means being away from family and friends. The journey to Romania will be an expedition to an unfamiliar world where unknown tests and adventures await.

Walter Murch with the director of Julia, Fred Zinneman.

Even in the edit, far from the set, there will be long nights, missed meals, and tensions, so Walter uses the time leading up to a film’s start date to get in good physical condition. This being the week of the summer solstice, there is ample daylight to schedule four- or eight-mile runs every day. Sometimes he’ll go out along the open ridge tops bordering the seashore, where on days like this, you can see the Farallon Islands 30 miles out into the Pacific; other runs are through shadowy coastal glens where bay trees give the redwood forests a tangy scent.

June 7, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Run Arroyo Hondo, which is exactly 2.5 miles. On the trail, I suddenly come across a woman taking a piss by the side of the road. “Hello” I say. She says nothing. Later on, I meet two guys coming back toward me—they were probably all camping together, and the guys had taken a hike so she could do her business. Maybe.

Thirty years earlier, in the fall of 1973, when Cold Mountain was a just another peak in North Carolina, Murch took a noteworthy eight-mile run that began, as they all do, down the dirt driveway through his front field. Murch had The Conversation on his mind—his first film as a film editor. He made a right at the street and headed west. Four miles down the road, the aging asphalt gives way to dusty dirt. It’s an ideal run, since few cars travel here. Walter had been working for almost a year on The Conversation, written and directed by Francis Ford Coppola, starring Gene Hackman as Harry Caul, the idiosyncratic eavesdropper, and expert in sound bugging whose anti-hero point of view lies at the heart of the story. At the moment, thought Murch, things weren’t going well.

Arroyo Hondo trail.

Up until The Conversation, Walter had created sound effects and edited them to fit the picture. He’d also been a re-recording mixer—the artist/engineer sitting at a mixing board who, at the very end of the filmmaking process, brings dialogue, music, and sound effects together at proper volume levels and equalization. By 1973 Murch’s feature film credits included Coppola’s The Rain People, (sound montage and re-recording mixer), George Lucas’s THX-1138 (co-writer, sound montage, and mixer), The Godfather (supervising sound editor), and Lucas’s American Graffiti (sound montage and mixer). He’d also edited picture on some documentaries, commercials, and educational films.

It is unusual for sound editors to cross over into picture editing. The film business is traditional and hierarchical; craft boundaries are strict and were even stricter in 1973. In part this is because each skill—be it lighting, cinematography, wardrobe, or editing—requires years of apprenticing and experience before you achieve proficiency. Then too, it can take longer to solidify your reputation in the business, becoming well enough known among producers and directors who make hiring decisions.

So it was a creative risk for both men when Coppola brought Murch on to edit picture as well as design sound and do the mix for The Conversation. Coppola wrote the screenplay in the mid-1960s, then put it away for several years. When he formed Zoetrope Studios in 1969, The Conversation was part of Zoetrope’s proposal of future projects to Warner Brothers. The package included Apocalypse Now, and American Graffiti, among others. As Walter dryly puts it years later, the executives at Warner Brothers felt these “weren’t interesting films,” and turned the package down. This devastating rejection led indirectly to Coppola’s signing with Paramount to direct The Godfather—a script that Elia Kazan, Fred Zinnemann, and Sergio Leone had already turned down.

But when The Godfather was released and became an instant critical and commercial success—at that time the highest grossing film ever—Hollywood became very interested in Coppola. Paramount wanted him to get started immediately on a sequel, The Godfather: Part II, but Coppola would only agree if the studio would first let him make The Conversation.

The problem was how to squeeze in The Conversation between the end of The Godfather and the start of production on The Godfather: Part II. The solution was for Coppola to be less involved with editing The Conversation on a daily basis, and that was a precondition when he asked Murch to edit the film. Coppola would plunge into development on The Godfather: Part II as soon as he was finished shooting The Conversation—casting, choosing locations, rewriting the script, and all the thousands of overwhelming tasks that occupy a writer/director/producer. The plan on The Conversation was that Coppola would show up every month or so, once Murch and associate editor Richard Chew (it was his first feature, too) had the film assembled. The three of them would screen it, spend a couple of days together going over ideas and making lists of things to try out. Then Coppola would disappear for another month into the maelstrom of The Godfather: Part II preproduction.

“The first assembly of The Conversation was long,” Murch continues, “just under five hours, so one overriding issue was how to get the film down to a releasable length. Needless to say, this wasn’t the usual kind of editor-director relationship. But it was my first feature editing job, and since I had nothing to compare it to, it seemed normal. Richard and I were working on Zoetrope’s new KEM 8-plate editing machines and relished the technical challenges and the freedom. Francis told us that if we thought of anything that wasn’t on the list we had, we should just go ahead and try it out without bothering him; he would see it when he next came back to town. The first assembly was completed at the beginning of May 1973—about six weeks after the end of shooting—and we went along like this for the rest of the summer: screening every month, then revising and shortening the film.”

Gene Hackman as Harry Caul in The Conversation, directed by Frances Ford Coppola. The first film edited by Walter Murch.

From The Godfather, directed by Francis Ford Coppola. Its success made it possible for him to then direct The Conversation.

Adding to the uncertainty of making a comprehensible motion picture was the fact that ten days of shooting never took place. Because the picture had gone over budget and was behind schedule, 15 pages of the original screenplay—10 percent of the needed material—was never shot.

“There were three areas of struggle,” Murch said later. “Trying to reduce the overall length while keeping things coherent; finding some way to re-knit the story line to compensate for the missing days of shooting; and a more fundamental issue of balancing the story’s two thematic elements—character study and thriller—since Francis had conceived the film as an unlikely fusion of Herman Hesse and Alfred Hitchcock.”

Murch and Chew made progress in finding solutions to the first two problems, but the third—balancing the two themes—proved to be more difficult. Coppola’s monthly screenings in the projection room at his home in San Francisco would always include several “civilians” who knew nothing about the film or indeed nothing about the film industry. These audiences admired the work-in-progress but were unclear about what had really happened at the end of the movie. More crucially, they also found it hard to identify with the introspective, socially uncomfortable central character of Harry Caul, and felt the thriller parts of the story did not integrate with the character study, or vice-versa. The editors tried different solutions, but audience reactions remained the same. By September, five months after finishing the first assembly, Coppola was getting worried. He was about to start shooting The Godfather: Part II, and The Conversation remained unfinished and problematical.

Murch and Chew flew to Lake Tahoe with the latest version of the film. Coppola was shooting the spectacular, party scene for The Godfather: Part II. They screened The Conversation in the evening and developed a new series of notes, but everyone could see that Coppola was consumed by the logistical and creative demands of The Godfather: Part II. At the beginning of October, Coppola called Murch with a bombshell: he had decided to suspend work on The Conversation until after The Godfather: Part II was finished.

On the outbound leg of that run in 1973, Murch passed a Coast Guard facility. There, overlooking the ocean, what look to be conceptual sculptures support webs of antenna wires. This array uses great power and coherence for ship-to-shore communications, and it would fascinate someone caught up by all things audio, like Harry Caul—or Walter Murch. But on that day Walter was focused on what to do about The Conversation. Should he go along with Coppola—his mentor, the first director to give him a shot at picture editing—and halt the edit?

Richard Chew, who co-edited The Conversation with Walter Murch, went on to win an Oscar for editing Star Wars, along with Paul Hirsch and Marcia Lucas.

The dirt road soon comes to a dead end and the coast trail begins. Four miles to the east lies the San Andreas Fault. This is where the Pacific plate, moving northwest, meets the North American tectonic plate traveling southeast. Their grinding together caused the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Ground zero was not far away. In a single violent moment, the earth now under Walter’s running shoes had leapt 20 feet to the north. Many violent temblors like the one in 1906 have been bringing most of Northern California and Southern California closer together for millions of years. This geologic activity, an excruciatingly slow conveyor belt, keeps nudging Hollywood (on the Pacific plate) inexorably closer to the Northern California film community (on the North American plate) at an average rate of 35 millimeters (the width of motion picture film!) every year. In a little over 16 million years, Sunset Strip will lie just offshore of San Francisco.

By now, Murch was running back the way he’d come. And he had made his decision. He describes the moment 30 years later, still fresh as highland water: “I decided to kick against the idea of postponement, convince Francis that I could fix what was wrong with the film—somehow find the right balance between the thriller and the character study—and come up with a plan to finish it on time.”

The Coast Guard radio antenna array along the route of Walter’s run.

Coppola agreed to let Murch have one final crack at the film, and when they screened it a couple of weeks later the new version seemed to have done the trick. The Conversation was released in the spring of 1974 at the height of the controversy over Nixon’s Watergate tapes; it went on to win the Palme d’Or at the Cannes Film Festival. The Godfather: Part II was released in December of the same year, and both films received Academy nominations for Best Picture of 1974. The Conversation was also nominated for Best Original Screenplay and Best Sound. The Godfather: Part II was nominated for eleven Oscars and won six, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay, boosting Coppola’s career to an even higher level than it had reached with The Godfather. Murch later won two British Academy Awards for his editing and sound work on The Conversation.

“If we had postponed,” Walter says now, “The Conversation would have probably come out in late 1975, but with a cloud over it which would have been blamed on me—a re-recording mixer who had never edited a feature before. And the crucial topicality of Watergate would have been lost. Both Francis and I had a lot invested in the film coming out on time.” Murch couldn’t know it then, but the challenges he faced in The Conversation as a rookie editor—solving major structural, storytelling problems, often working autonomously of the writer/director—would soon become as familiar to him as his favorite running trails.

The Conversation begins with a young couple, Ann and Mark (played by Cindy Williams and Frederic Forrest) walking through San Francisco’s Union Square at lunchtime, having a conversation they don’t want overheard. Harry Caul, the “private ear,” has been hired by the young woman’s husband (the “Director,” played by Robert Duvall) to record the couple with several hidden long-range microphones. Back in his workshop, Harry Caul uses his sophisticated technology to uncover a key line from the partially garbled conversation, as spoken by Mark: “He’d kill us if he had the chance.” Harry becomes more and more convinced that the Director might be planning to have the young couple killed because they are having an illicit affair. This weighs on Caul’s guilty conscience: it won’t be the first time his snooping resulted in someone’s murder.

Work-in-progress audiences were having problems understanding the intricacies of the plot because Harry himself doesn’t fully understand what he has gotten involved in, and the story is told strictly from his point of view. Given the structure of the screenplay, there was no easy way to swing outside events and show them in wide shot, so to speak.

During production, while Frederic Forrest and Cindy Williams were still easily available, Murch took them to Alta Vista Park, a quiet square in a residential neighborhood of San Francisco, to record a complete take of their conversation, audio only, in case he needed “clean” dialogue to augment the original production sound which was being spoiled by microwave interference. In that “wild sound” recording with Murch, Forrest did one reading of the “kill us” line with an unintentionally different emphasis. Instead of saying, “He’d kill us if he had the chance,” implying that the couple is in danger, Forrest accidentally read it as, “He’d kill us if he had the chance.” Says Murch: “That makes you imagine three dots at the end of the line, and in parentheses at the end of the line, the implied conclusion: ‘So we have to kill him.’”

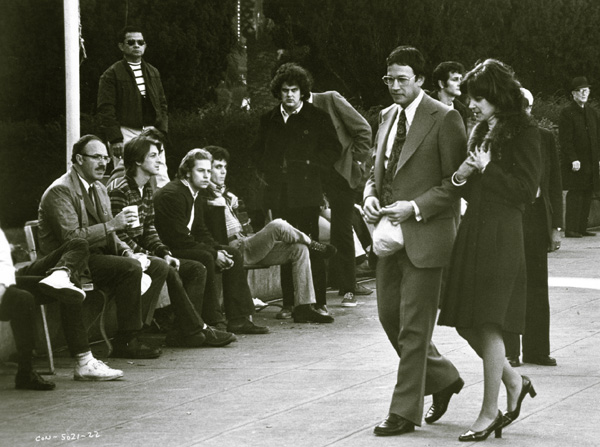

Frederic Forrest as Mark and Cindy Williams as Ann in The Conversation. Notice Gene Hackman (Harry Caul) on the park bench.

Murch re-recorded dialogue for this scene, and by chance got a line reading he later used in editing to clarify the story.

“I noted that reading at the time,” Murch continues, “and filed it away as being inappropriate. But a year later during the mixing of the film I suddenly thought, let’s see what happens if we substitute that ‘inappropriate’ reading with its different inflection into the final reel. It might help tip audiences into understanding what had happened: that the ‘victims’ were really the ‘plotters.’ So I mixed it into the soundtrack in place of the original reading and took the finished film to New York where Francis was halfway through shooting The Godfather: Part II. I prepared him for the change and wondered what his reaction would be when he heard it. It was a risky idea because it challenged one of the fundamental premises of the film, which is that the conversation itself remains the same, but your interpretation of it changes. I was prepared to go back to the original version. But he liked it, and that’s the way it remains in the finished film.”

“Harry Caul is sophisticated technically but stunted emotionally,” Murch says, “and he used all of his sophisticated technical filters to uncover that one critical line of dialogue. But the significant distortion he didn’t remove was the one in his mind. He was falling in love with Ann (the Williams character) at a distance, and he so needed to believe she was a victim that he subconsciously placed the emphasis on kill rather than us. At the end, after the Duvall character is discovered to have been murdered in the hotel room, the mental distortion falls away and Harry hears the line the way it really must have been all along.”

Another example of Murch’s active participation in constructing The Conversation was seizing an opportunity to add intrigue, and coincidentally help fill the hole created by unshot footage. Just past the halfway point in the film, after attending a surveillance trade show, Harry Caul invites his colleagues and acquaintances to come back to his loft office for an informal party. There’s drinking and continued confrontation between Harry and Bernie Moran, his rival, played by Allen Garfield. Moran’s assistant Meredith (Elizabeth MacRae) seems to be intent on seducing Harry. The tape of Ann and Mark’s Union Square conversation is still up on Harry’s tape recorder.

“One of the things that emerged in the editing of the film was the idea of making Meredith steal the tapes,” Murch says. “In the film as it was shot, she stayed with Harry, slept with him in his office, and was gone when he woke up, having stolen some electronic diagrams that Moran had coveted. But I found if we could insinuate that she had stolen the tapes, then several lines of the story would come together—implying that her boss Moran was in cahoots with the Director’s assistant Martin Stett (Harrison Ford) to get the tapes which Harry was holding on to. But all of that was constructed in the editing. In the end we found we had to shoot just one extra shot—Harry’s hand on an empty reel—to tie it all together.”

Something of Murch is in the Harry Caul character. They’re both fascinated by sound, recording equipment, and how audio can be manipulated and its meaning redefined. They don’t mind—maybe they prefer—working alone. Harry plays the saxophone, which seems to be his only form of relaxation. Walter considers editing a musical form—visual music. This superimposition of character and film editor became evident during the edit of The Conversation. One late night, on the edge of exhaustion and deep inside movie space, Murch was working on a scene in which Harry Caul stops his tape recorder. Murch couldn’t understand why his KEM editing machine didn’t also come to a stop on Harry’s command. Who was controlling whom? It’s an obvious question: did Coppola model Harry Caul on his freshman editor when he wrote the screenplay for The Conversation?

The party scene in The Conversation. Murch reconstructed the end of the scene to imply that Meredith, played by Elizabeth MacRae, steals Harry Caul’s tapes.

The experience of working so independently on The Conversation gave Murch the methods, approach, sensibilities, and confidence that would define his editing work for the next three decades. In Murch, directors like Coppola, Zinnemann, Minghella, and others know they’ll be working with a skilled film editor, no question. But more than that, they will be bringing a creative partner aboard: a co-pilot capable of flying the plane when the director needs to focus attention elsewhere; a flight engineer who can respond to mechanical problems with elegant solutions to keep the machine airborne; and a navigator finding added meaning and poetry that were never fully spelled out in the flight plan.

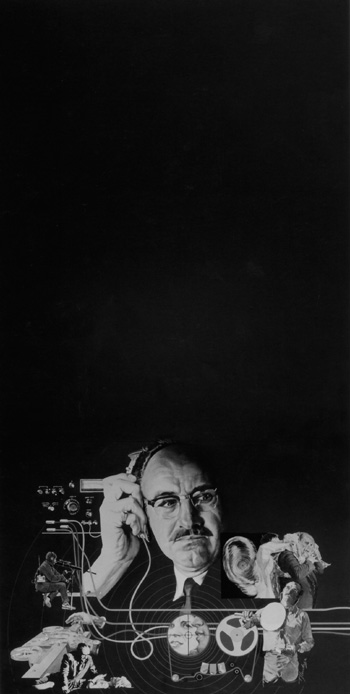

Artwork for The Conversation poster.

From: Walter Murch

Date: 6/8/02

To: Anthony Minghella

Dear Ant:

Have received and am reading the new CM - wonderful work! - and will finish it today, have a timing for you hopefully Monday - Tuesday. I like the longer opening in CM before we go to war. Have an idea about that transition, but will wait to think more about it until I finish.

Have a great time location scouting!

And congratulations again on the new version!!

Love,

Walter

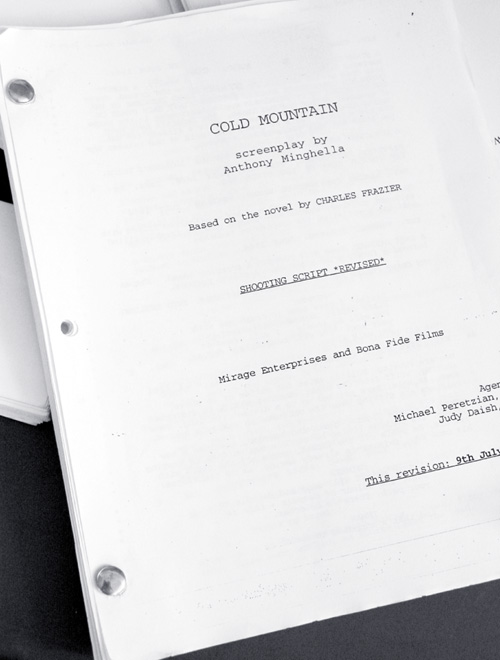

The screenplay of Cold Mountain.

Now, 30 years and 27 films later, Murch is preparing for another plunge into the bracing waters of a high-budget, high-profile, studio-backed motion picture: Cold Mountain. For this he needs to reread the screenplay, write up his notes for director Anthony Minghella, and perform a ritual “script timing.” This involves reading the screenplay to himself in “film time,” measuring each scene’s duration with a stopwatch as it plays in his head. He’ll do this exercise three separate times to see if the film “runs” consistently. If it does, fine; he’s found the bedrock of the film’s tempo and length. If the timings do not agree, that may indicate a fault line running under the film’s surface—a fissure that could cause rumblings later in the editing. This is certainly not the last window of opportunity to raise concerns with a director about structure, tone, and comprehensibility. Walter and Anthony will sit with these issues every day, like family at the dinner table, throughout the filmmaking process. But this is the only chance for Murch to share his thoughts and worries about story and character before the tornado of production moves in and sucks up most of the oxygen. And since they still exist only on paper, for the moment these issues remain theoretical problems, snugly confined to the upstairs office in Murch’s barn.

Cold Mountain has a story structure that is the antithesis of the one in The Conversation. Instead of being locked into a single protagonist’s point of view, the award-winning, best-selling novel by Charles Frazier uses a parallel, multiple point-of-view construction. Inman (played by Jude Law), is a Confederate soldier injured in the Battle of Petersburg who deserts from the army and travels as an outlaw for many months over hundreds of miles to return to the woman he loves, Ada Monroe (Nicole Kidman). Ada is an aristocratic minister’s spinster daughter who waits for Inman in Cold Mountain, North Carolina. There she struggles against Home Guard vigilantes, hard winters, and her own inadequacies to hold onto her farm, Black Cove, after her father has died. Inman and Ada have had a brief taste of romance before secession leads to war and forces them apart, but the film tells of their respective travails separately. Only at the end are they reunited.

June 9, 2002, Murch’s Journal

Eight Miles. Last three up the hill and then another mile on ridge trail south, and back. Lovely weather, the triptych smell of pine, eucalyptus, and bay laurel in hot sun, three braids intertwined. Town lovely and mysterious 1000 feet below. Why mysterious?

I went for a swim in the channel—cold—but not crampingly so. I told myself that this is the ritual baptism, allowing me to be reborn from K-19 onto Cold Mountain. I went in three times, each time a little longer, and by the end of the third, floating out to sea, I could not feel the cold. In fact, it felt in some metaphysical way warm. Lovely day, blue sky, warm inland wind, the town putting on its finest for me, who is about to leave it.

Among Murch’s many working methods is “The Memo”: a set of notes, usually six to eight pages long, that he gives a director before principal photography begins. Sometimes, as Murch describes it, The Memo is the first and last thing he does on a film. A few directors have changed their minds about having Murch edit their film, once they read the extent of his critique and grasped how intimately involved he would be in the project. Either way, these first notes serve Murch well.

From: Walter Murch

Date: 6/10/02 2:06 AM

To: Anthony Minghella

Dear Ant:

Congratulations on the new draft—a couple of tear-stinging moments for me, even though this is the third read.

I am going to be timing it tomorrow and Tuesday, if I can keep the rest of my life at bay and find that lovely stopwatch.

Structurally, of course, lots (50+) transitions back and forth in space and time. Presents its own challenge, as we know from EP [The English Patient], which had 40 transitions. But it will be wonderful.

However, how to articulate the moment when back and forth in time becomes back and forth in space? It is a little confusing to track it now, if I put on my audience hat.

When Inman nods to Mrs. Morgan (page 26), a clock starts ticking faster, faster, and the sooner he gets out on the road the better.

Once Veasey and Ruby enter the film, it rockets along.

I have put so many check marks (good!) on almost every page from 35-100 it is stunning. Lines and moments that any film would be happy to have a half dozen of, here there are scores and scores.

I wonder, that the interlude with Sara, and the fact (debatable, but still...) that Inman and Sara sleep together, undercuts his meeting with and sleeping with Ada. The two scenes are in such close proximity. And then the fight with the Northerners, and Inman’s actions to save Sara and her baby, are similar in tone to his actions against Teague and Co. to save Ada and Ruby. There is a kind of musical reiteration, thinking of it symphonically, that may undercut the most important moments, which are those with Ada and the shootout with Teague & co. Perhaps I am missing something...

Is there a way to hint at the ambiguity of Inman’s death, the way the book did? If we know he is dead, then the coda feels more... coda-like, and a little too sweet, somehow.

Relationship between Ada and Inman:

More tension, and more class distinction. Make it more IMPOSSIBLE, UNTHINKABLE for these two to get together, so that when it does, it is the more rewarding. What she goes through on Black Cove Farm causes her to grow in stature, and understand and love Inman. The early scenes are all pretty easy now, except for Inman’s taciturn nature. Everyone (Sally, Monroe) is kind of nudging them together. And Ada is very willing. Make her less so, more complex, and paradoxically less self-aware: a dose more Scarlett O’Hara, not as completely accepting of Cold Mountain’s charms and people.

All of this is present, latent, in the structure now, but I am suggesting finding a way to draw the bow a bit further back at the beginning so the arrow has more force.

=========

Excuses, as always, for the lack of “perhaps” and “maybe” and “it seems to me” which are hovering invisibly around every phrase of these comments.

It is and will be a fantastic film.

Love,

Walter

Minghella, who is having production meetings and scouting filming locations in North Carolina, answers Murch two hours later:

From: Anthony Minghella

Date: Mon, 10 Jun 2002 07:16:24 EDT

To: Walter Murch

brilliant brilliant notes, and I’m intrigued by each of them. I don’t know how to address them all, but I am already contemplating new moments and improvements. I’m particularly keen to make the return of Inman to Ada sing more. And I understand what you mean about Ada and Sara. It’s one of the things which prompted me to cast Natalie, who is so young, and finally not a real threat to Ada, but but but. I also know what you mean about Ada and the absence of thistle between her and Inman. I know I can make it better. I know that the budget battles, continuing today with a big meeting on our one rest day of the technical survey (on which I’m also scouting) means that my brain is more occupied by numbers, by cuts, by the indifference to content, than it is with issues of content.

Jude Law as W.P. Inman in Cold Mountain.

I am so happy to get your mind patrolling this material. Keep scratching away. I’m thrilled that you see what we have here; I’m thrilled that you’ll push me to make it better. Did you look at the storyboards? They’re already simplifying and simplifying, and I’m very conscious of the sequence in terms of length, but I’d love your scouring of their implications and their narrative transparencies.

off to battle myself

ant

According to time-honored Hollywood tradition, film school graduates who want to become movie executives break into the system by taking a job in a studio mail room. In fact, many entertainment industry agents-to-be still begin their climb to the top by wheeling mail carts through the decorous halls of such big talent agencies as Creative Artists Agency (CAA), William Morris, and International Creative Management (ICM). Similarly, Walter Murch’s first paying film job was nowhere near an editing room or film set, though it did involve legendary Hollywood director George Cukor (Dinner at Eight, The Philadelphia Story, My Fair Lady).

When they were all students at USC, Murch’s friends George Lucas and Matthew Robbins saw a bulletin board posting for a temporary job over winter break. It turned out that George Cukor needed people to help wrap and deliver his annual bounty of Christmas gifts. Lucas quit after one day, so Robbins recruited Walter as his replacement. In Cukor’s attic they found a pyramid of gifts—at least 250 of them—for the director’s closest friends, actors, actresses, and film business cronies. Robbins and Murch soon became expert in wrapping techniques, as well as navigating their way around Beverly Hills, Brentwood, and Bel-Air. They tootled around in Robbins’s VW van, ringing doorbells, with Walter going up to imposing front doors and announcing to the butler or maid, “A gift from Mr. Cukor.” Occasionally Cukor would appear at the door of his attic to monitor progress. Murch still remembers Cukor’s advice (borrowed from Benjamin Disraeli): “Never complain. Never explain.” It became a saying the film student would retain and rely on: work hard, get the job done, and don’t bother explaining why something didn’t get finished. No one cares about excuses.

(Walter later figured out that Cukor was using the holiday seasons to recruit Christmas helpers for his own extra-curricular entertainment: “the elves in the attic,” as Walter calls them. “That year he struck out. But he was very good-natured about it.”)

After leaving USC in 1967, Murch first went to work in the film business—for real this time—at Encyclopedia Britannica Educational Films (replacing Robbins, who was moving on to something else), and he soon got his chance to edit picture. Later he went to Dove Films, a commercial production company run by two cinematographers, Haskell Wexler and Cal Bernstein. At both places, Murch was working with the Moviola editing machine.

Forty years earlier, before the invention of the Moviola, the edit room was a quiet place outfitted simply with a set of rewinds, scissors, and editor’s intuition. Stitching together a film was analogous to sewing, and many editors in those days were women. After seeing new footage projected once, editors went over the film with a magnifying glass, choosing where to make cuts based on their recollection from that one screening. Their only rule of thumb: a length of film held from the tip of the nose to the end of an outstretched hand would run for about three seconds. Strips of film were put together with paper clips and sent off to another room to be hot-spliced together with acetone film cement. After this new assembly was screened for the director and producer, the editing process continued, with adjustments made as necessary until the final version was approved.

Editing department, Triangle Pictures Corporation, 1917.

So things remained until Iwan Serrurier, who was neither an editor nor a film worker, invented the Moviola, the world’s first editing machine. A Dutchman, he came to the U.S. at the turn of the 20th century, made a fortune in real estate, and became intrigued by the technical advances taking place here. Serrurier’s initial idea was to invent a film-viewing machine for the home, (comparable to the Victrola for playing records)—the first home entertainment system. He built a model with beautiful cabinet work, and got it patented; one of his five children named it in a family contest. Priced at $600 in 1920 (about $5,600 in today’s dollars) his machines were beyond the reach of a normal household. So who could afford them? Serrurier thought studio executives might use the Moviola to view dailies in the comfort of their own offices.

Serrurier went to the movie studios but succeeded in selling just three machines. Only after going to the Douglas Fairbanks Studios (the same facility where Walter worked on K-19 some 75 years later) did Serrurier finally see how movies were being put together. He watched an editor trying to move the film back and forth by hand to get the equivalent of a moving picture. The man told Serrurier he might be interested in the machine if it were modified for use on an editing bench. Over a weekend, Serrurier retooled the Moviola for professional use, stripping it of its varnished wood cabinet, and on Monday brought the revamped prototype back to the editor. The Moviola was a hit, and in 1924 Serrurier sold his first editing machine to Fairbanks Studios for $125 (about $1,370 today—not much more than the cost of Apple’s Final Cut Pro edit system).

Demand for Moviolas took off during the 1930s, then boomed during World War II, when hundreds of military and propaganda films were being produced each year. All the newsreels shown in theaters to keep Americans abreast of the latest war developments were cut on Moviolas. Serrurier’s company added a small editing bench and splicer and shipped these self-contained post-production units overseas. The first “broadcast journalists” shot, processed, and edited short films on location, then sent the newsreels home. They were the precursors of today’s field reporters, who use satellite-linked cameras to send TV and Web-delivered news clips of events as they occur.

An upright Moviola editing machine, the type Murch first used when he began working in the film industry.

By the time Walter Murch first encountered the Moviola, it had been in use with few changes for over four decades. It still had its beefed-up sewing machine motor, forward and reverse foot pedals, exposed flywheel, and a hand-brake. The editor, working standing up or perched on a stool, watched a smallish image flicker on a viewfinder no bigger than a postcard. With the help of an assistant who stood behind hanging up “trims” (small clips of film), the editor slowly built up a reel of good takes. Each reel had a maximum capacity of 1,000 feet, or just over 11 minutes. For sound, the Moviola could handle one separate reel of audio that had been transferred from ¼-inch tape to 35mm magnetic film—essentially audiotape in 35mm gauge.

The frustrations of editing on a Moviola are legendary. The machine loves to eat film, scratching or chewing up workprint inside its uncompromising steel mechanism. The intermittent motion of the film clatters noisily. The viewing image is small. And by only being able to run one audio track at a time, it gives the editor little control over sound, aside from dialogue.

The first flatbed film editing system, an alternative to the Moviola, was introduced in Germany by Wilhelm Steenbeck in 1931. The Steenbeck, like the later model made by KEM, provided a larger image viewing area, virtually silent operation, a rotating-prism lens, three tracks of sound, and a generally more comfortable working environment. The editor could now work sitting down as if at an office desk, instead of standing up at the Moviola like a lathe operator. When Coppola began planning his edit for The Rain People on a trip to Europe in 1967 and brought back a Steenbeck editing machine, it was the first flatbed to be used, by editor Barry Malkin, on a motion picture in the U.S.

So in 1972, another challenge for Murch on The Conversation, in addition to editing his first feature and dealing with seemingly intractable story problems, was the new editing machine he was using—this one a huge, gray, ultramodern KEM Universal “8-plate” flatbed, similar to the one that Thelma Schoonmaker had used to edit Woodstock in 1970. Until The Conversation, all of Murch’s picture editing experience had been on the traditional upright American Moviola. The sleek German KEM had two rotating-prism screens, was push-button operated and capable of playing three tracks of sound at the same time. But it required film workprint to be strung together in large 1000-foot (11-minute) rolls of consecutive shots, rather than spooled into cupcake-sized individual takes a minute or two long, as used on a Moviola. The two machines require working in different modes, which Murch likens to a sculptor using different materials: instead of building up the “sculpture” of the film from small bits of “clay,” as would have been the case with a Moviola, editing with a KEM involves chiseling away chunks of “marble” from large blocks of film, ultimately revealing the movie hidden inside.

A KEM Universal flatbed editing machine.

Although it is a mechanical device, the Moviola is in fact a non-linear system with more organizational similarities to random-access computerized editing than to the linear KEM system. Consequently Murch’s change to the linear KEM from the non-linear Moviola actually required more of a wrenching conceptual shift than the shift he would eventually make from film-based editing to digital editing. After The Conversation, Murch would switch back and forth between KEM and Moviola over the following 20 years, depending on the director he was working for and the editorial style of the film.

From Apocalypse Now, directed by Francis Ford Coppola. Murch used an Avid to edit Apocalypse Now Redux, the director’s cut, released in 2001.

Thus began, on his first feature film, Murch’s participation in the search for the filmmaker’s Holy Grail: a technique for assembling motion pictures that would be fast, cheap, and transparent; immediately responsive to creative ideas without the process itself getting in the way; and a method of reproducing film image and sound as near as possible to what audiences experience.

As early as 1968, Coppola, Lucas, and Murch had been investigating a precocious attempt at computer-controlled editing. The CMX film-editing computer, like mainframes of the day, was expensive and bulky, filling an entire room with hardware, but it gave Murch a glimpse of the future. A few years later, Coppola and Murch proposed using a more developed CMX system to edit parts of The Godfather, but the studio turned them down, citing unreliable data storage and exorbitant costs.

By the late 1970s and early ’80s, as the personal computer came of age and began to revolutionize home and work, many different computer-based film editing systems came along: E-Pix, EMC, D-Vision, Lucasfilm’s EditDroid, and others. As Murch points out in his 1995 book, In the Blink of an Eye, “A tremendous amount of research and development was invested in these systems, particularly when you consider that, although professional film is an expensive medium, there is not a lot of professional film equipment in the world (compared, for instance, to medical equipment).” Of course, television offered more business opportunities, and digital post-production took off worldwide in the broadcast industry. In all of these early systems, the computer was used simply to control the movement of analogue media (VHS tapes, laserdiscs, etc.) stored on transport devices that were umbilically linked to the computer.

By the late 1980s, speedier processors and better data storage capabilities made it possible to digitize film images directly to a computer’s hard drive. After getting its inauguration on commercials and high-end documentaries, the Avid editing system for film began to appear in feature-film editing rooms. Murch’s initial experience with Avid was on a music video for Linda Ronstadt in 1994, and for a short, layered sequence in the 1994 film, I Love Trouble. The first feature film he edited entirely on the Avid was The English Patient. The Avid was his system of choice on the next several films: The Talented Mr. Ripley, the recut of Orson Welles’s Touch of Evil, Apocalypse Now Redux, and K-19.

But the Avid had certain limitations and difficulties. For one thing it is relatively expensive. The Avid Film Composer, which simulates film editing and contains the necessary film-to-video conversion protocols, cost $80,000 to $100,000 when Murch first used it in the 1990s, so feature-film budgets would normally allow for only two machines, at most. (Some films limped along with only one.) Even with two machines, one of them is usually dedicated to doing all the “housekeeping,” such as file management and making tapes for other crew members—sound editors, music composers, producers. The Avid is a “closed” system, meaning its architecture is designed to run only proprietary software, and its way of digitizing and replaying the image is unique. Expensive new versions and upgrades have to be purchased, and only from Avid. Finally, for a long time the company was infamous for providing spotty technical support and resisting innovation and input from filmmakers.

As he worked on Avid systems, Murch kept his eye on other developments in the digital editing world. Premiere, by Adobe Systems, came out in 1991. The software was suitable for commercials, documentaries, and other projects originating on video, but it couldn’t translate 24-frame-per-second film into 30-frame-per-second video.

Meanwhile, the San Francisco-based media software developer Macromedia was having great success with programs for multimedia and Web development, such as Director, Dreamweaver, and Flash. It had been working on a digital editing system called Key Grip, that could operate on Apple’s Macintosh, but the company was concentrating on Web tools and didn’t see much future for its new editing application, and so sold it to Apple in 1998 before ever releasing a finished product. In 1999 Apple released a revamped version of Macromedia’s application as Final Cut Pro, a digital editing system designed to compete with Premiere for consumers, students, and low-end professionals. This caught Murch’s eye, as it caught the attention of other film editors on the lookout for technological advances. He had been using a Macintosh since 1986 and has always been a fan of Apple. He liked the company’s belief in supporting professionals in the creative arts with tools that were innovative and responsive to users’ needs.

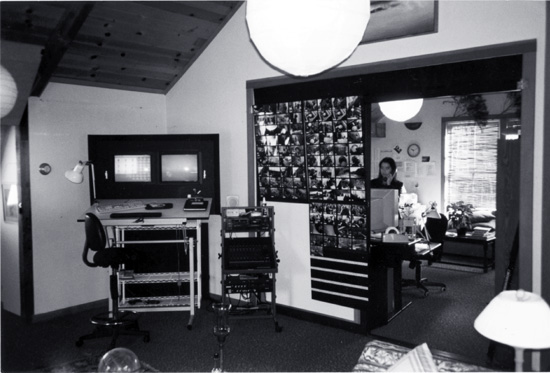

Murch first used the Avid Film Composer on The English Patient when he had it set up in his office at home. Assistant editor Edie Ichioka, seen above, describes it as, “a surreal setting for editing, with a wood-burning stove, and chicken clucks in the morning that aren’t coming out of your edit machine, but are actually coming out of chickens in the barn below.”

In June 2002, Walter was preparing to leave for Romania to start work on Cold Mountain. The project meant being out of the country for a year and a half. He’d barely had time to catch his breath, having finished sound mixing on K-19 only four weeks earlier. This would be his third picture with director Anthony Minghella, so Walter knew how Minghella liked to work: shooting an abundance of material for later review and editing; constantly re-examining assumptions about story, structure, and character; and revising picture and sound right up to delivery of the final mix and cut negative. As with their two previous films, Murch would be both picture editor and re-recording mixer. Now, as if he didn’t already have enough challenges ahead of him, Walter was thinking about making another dramatic jump-shift in editing methodology: editing Cold Mountain with Final Cut Pro—Apple’s $995 off-the-shelf software. Had his desire to find the Holy Grail of film editing become an obsession? Was Murch getting too far ahead of the pack, becoming an errant knight? He may intrepid, but Murch isn’t reckless. His longtime assistant editor, Sean Cullen, helped Murch weigh the risks and locate the most qualified sherpas available to guide their journey—but they were not in Cupertino. People at Apple reacted variously to the news about Murch’s intention to use Final Cut Pro, ranging from euphoria and excitement to caution and deep misgivings. So for help, Murch and Cullen instead went to a 1920s Tudor-style building on Sunset Boulevard in West Hollywood, halfway between the Whisky a Go Go and the Roxy nightclubs.