7. Rebuilding Your Score After a Credit Disaster

So you’ve weathered the financial storm. Now what do you do about the mess that was left behind?

Your credit file might be littered with delinquencies, collection actions, repossessions, or even bankruptcy. You might worry that these mistakes will haunt you forever, or at least make getting credit terribly difficult and expensive.

Some people are so frustrated with their bad credit that they simply give up. Maureen in Cleveland wrote me about her daughter and son-in-law, who were turned down for several loans after filing bankruptcy. Humiliated, they vowed never to approach another lender:

“They’ve given up on their dream of owning their own house someday,” Maureen wrote. “I know they could do something about their credit if they would just try.”

Contrast their attitude with that of Chance, an Indiana loan officer who filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy five years earlier at age 27:

“Today I have a 697 middle score, and I can get a loan for anything I want to,” Chance wrote. “I own a home and two rental properties, have a brand new auto and motorcycle.... Being in the mortgage industry, I knew I could overcome the bankruptcy, because I knew how the credit system worked.”

Lenders’ willingness to give people a second chance waxes and wanes along with the economy. In bad economic times, those with bad credit usually find it harder to get the accounts and loans they need to rebuild their credit. But there will still be ways to get started.

Credit-scoring formulas care more about what you’ve done recently than what you’ve done in the past, so making the right moves now can set you on the path to good credit.

You won’t be able to erase your mistakes overnight. However, most people with past credit problems can achieve a substantial boost in their credit scores within a couple years. By the time the last negative item drops off your credit report—after seven years for most black marks, or up to ten for a Chapter 7 bankruptcy—you could have a credit score that’s actually better than average.

Part I: Credit Report Repair

Many people who have credit problems are terrified at the prospect of looking at their credit report. It’s the same dread they might have felt as children about a bad report card, only amplified by their adult knowledge of how destructive poor credit can be.

In actuality, your report might be better than you think. Some of the problems you are worried about might never have been reported to the credit bureaus, or they might have less of an effect than you fear.

However, your credit file might be a bit of a nightmare, with every slip-up documented in black and white. Your report might even make your problems look worse than they actually were. It’s not uncommon to have two or more collections reported for the same debt, for example, or for other errors to creep in that can hammer your credit score.

You might, for example, be the victim of an unscrupulous collection agency that has illegally “re-aged” a debt—in other words, reported the account to the credit bureaus in a way that makes your mistake look more recent than it actually is. Beth in Los Angeles wrote about just such a scofflaw:

“My husband and I had a dispute with a cable company over a box that they never gave us, but that they claimed we owed $200 for when we closed the account before we moved. To make a long story short, the item ended up on our credit report as a collection account.

“We waited anxiously for that to roll off of our report. At the six-year, two-month mark, another collection agency called us. They said they had bought the account, and that the seven-year ‘clock’ started again when they bought it. They said unless we paid them, they would report it as a new debt and it would remain on our credit report for seven more years.”

The good news is that you’re not helpless. There are steps you can take to clean up your credit, chase off mistakes, fight back against illegal tactics, and even—perhaps—scoot some of those bad marks off your report without having to wait for the usual seven- or ten-year period to expire.

Scrutinize Your Report for Serious Errors

Your first move is to get copies of your credit reports from all three bureaus, using the addresses or Web sites listed in Chapter 4, “Improving Your Score—The Right Way.” Make sure you get three separate reports, rather than a “3-in-1” or “tri-merged” report that combines information from the three bureaus. Although these merged reports are helpful to lenders, they might not include all the information that’s included in each bureau’s files.

Follow the steps listed in Chapter 4 for reviewing your report, noting any problems for dispute with the respective credit bureaus. Look especially for the following:

• Delinquencies that are older than seven years, or accounts listed as delinquent that don’t include the date of delinquency

• Bankruptcies that are older than ten years or that aren’t listed by the specific chapter

• Judgments or paid liens older than seven years

• Paid-off debts listed as unpaid

• Accounts that were wiped out by a bankruptcy filing still listed as “past due” instead of as “included in bankruptcy”

• More than one collection account for the same debt

• Collection accounts that don’t show the date that the original account went delinquent

• Any accounts, delinquencies, collections, and so on that aren’t yours

When it’s time to actually dispute the errors you find, you have a choice about whether to make your beefs online or by snail mail. Some credit repair veterans prefer to use the online dispute process that’s available when you get your reports via the Web; they believe there’s less likelihood of their disputes getting “lost” because the electronic process typically dumps their complaints directly into the bureaus’ computer systems. If you do opt for online disputes, make printouts of every form you fill out and every response you get. Doing so establishes the kind of paper trail that can be incredibly helpful if you run into problems.

The need for a paper trail is why others insist that all communication with bureaus, creditors, and especially collection agencies should be in writing and sent certified mail, return receipt requested. Keep the little green cards you get back, along with copies of the letters and any documentation you might submit. Because you’re probably new to the credit repair process, you might want to start out doing things the old-fashioned way and switch to the electronic process only when you become more comfortable with the system.

Know Your Rights

Before you dispute anything, though, you need to know your rights under the Fair Credit Reporting Act. They are as follows:

• The right to have your dispute investigated—The bureaus must investigate your dispute, usually within 30 days, by contacting the creditor, collection agency, or other “information provider” that supplied the data in question. Any information provider contacted in this way must launch its own investigation and report its results back to the bureau. The term “investigation” is a bit of a misnomer, though. Most of the process is highly automated, with the bureaus’ computers querying the creditors’ computers. Consumer advocates have long complained that the system bears little resemblance to a meaningful review of questionable data. The bureaus’ recent settlements with regulators offer hope that this will change, and that you’ll get a human being involved to help you resolve disputes. You still should expect a fight to get your record cleared, though. Also, there’s a major exception to the 30-day rule. If the credit bureaus decide your dispute is “frivolous,” they might tell you so and refuse to investigate. This tends to happen if you repeatedly demand investigations of information that’s already been verified. Although this can prevent scam artists from taking advantage of the system, it can be frustrating for people who are dealing with a creditor that refuses to correct its errors.

• The right to have erroneous information corrected—If the provider says the information is indeed inaccurate, it is required to notify not just the bureau that originally contacted it, but all the other major credit bureaus, too, so that the error can be fixed or the item deleted. If the provider can’t verify the information, the information must be deleted from your credit report.

The bureaus can, however, reinsert the deleted information or undo the correction later if the provider verifies that the original item was in fact complete and correct. This exception can frustrate the heck out of consumers who think they have their reports cleaned up, only to see the bad information pop up again after a few months.

• The right to a written response—After completing its investigation, the bureau must give you a written report of its findings and a free copy of your credit report if the investigation changed anything on your file. Furthermore, if the bureau later restores the information that was deleted or changed, it must notify you in writing and provide you with the name, address, and phone number of the information provider.

• The right to have a statement included in your file—If the dispute doesn’t resolve the way you want, you are entitled to a 100-word statement inserted into your credit report explaining your side of the story. As you read earlier in this book, though, these statements have no effect on a credit score. Therefore, even though you have this right, you’re much better off pursuing other avenues that can actually make a difference if you’re being stymied by a recalcitrant creditor.

• The right to sue—If a creditor or collection agency violates these rights—by continuing to report inaccurate, unsubstantiated information, for example, or failing to respond to your dispute—you can sue the creditor or agency in state or federal court. Some people have even pursued these claims successfully in small claims court. Hopefully, your problems can be resolved without a judge’s involvement. But you might need the threat of a lawsuit, and perhaps legal representation to back it up, if you’re dealing with a particularly troublesome creditor or unresponsive credit bureau.

Organize Your Attack

At this point, you should divide the errors you’ve discovered into two groups. The first group includes unpaid debts that actually belong to you (as opposed to debts that you didn’t incur or that belong to someone else), including any debt you suspect was illegally re-aged, and any collection accounts (whether they’re legitimately yours or not). All the other errors you discover—accounts that aren’t yours, old delinquencies on paid-up accounts, debts that were included in bankruptcy but aren’t listed that way, and so on—should be included in the second group.

You can get started disputing the items in that second group right away. Include copies of any documentation you have that supports your assertion with your letters to the credit bureaus. (Never send originals.) After you’ve notified the credit bureaus, follow up by sending a letter (certified, return receipt requested) to the creditor that supplied the erroneous information. Now all the creditors and the bureaus are on notice that there’s a problem. Failure to act on their part would be a violation of federal fair credit reporting rules and grounds enough for a lawsuit—again, if it comes to that.

In many cases, the creditors and bureaus will correct legitimate errors. However, you’ll still need to monitor your credit reports to make sure the bad information doesn’t pop up again in the future. If that happens, the paperwork you’ve kept—including notification that the bureaus give you about the changes they’ve made—might help you get the errors removed more quickly.

If the creditor or other information provider insists that its information is accurate, however, you might need to dispute the information with them again—or you might just want to head straight to a lawyer. Sometimes a firmly worded missive on an attorney’s letterhead is all it takes to get a creditor to see the error of its ways. If not, there’s always a lawsuit. The National Association of Consumer Advocates at www.naca.net can provide referrals to attorneys.

What You Need to Know About Unpaid Debts and Collections

Now let’s return to that first group of errors you identified—the ones dealing with collection accounts and valid, unpaid debts. These were segregated, because different rules apply.

When it comes to collections, you have another important right as outlined in the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act:

• The right to have a collection account “validated”—This process, as outlined in the FDCPA, is quite different from the “verification” process referred to previously. When a credit bureau asks a creditor to “verify” information, the investigation that follows can be pretty cursory. With verification, the creditor reviews its records and any information supplied by the consumer and then decides whether it (the creditor) was right or wrong.

When a collection agency is asked to validate a debt, by contrast, the process can get pretty involved. The collector must prove that the debt is your responsibility and that it has the legal right to collect it from you. Furthermore, the collector has to cease all collection activity until it provides this evidence to you. If the agency can’t validate the debt, it must end its attempts to collect on the debt and stop reporting the collections account to the credit bureaus.

Note that your right to validation applies specifically to collection agencies, not to the original creditor. Collection agency records are presumed to be less reliable than those kept by the original creditors. Collectors are often guilty of going after the wrong people or misstating the amounts owed; the validation process is meant to protect consumers from those practices.

To validate a debt, the collector needs to present documentation—obtained from the original creditor—proving that you do indeed owe the money.

Validation can be a powerful weapon in your fight to clean up collection actions on your credit report. Many times collectors don’t have the documentation required, especially if the debt has been passed around from one collection agency to another, as often happens. Frequently, they have little more than a computer printout to back up their claims, and the Federal Trade Commission has made it clear that such a “mere itemization” isn’t sufficient proof to constitute a validation of a debt.

The validation process can not only help you eliminate collection accounts that don’t belong to you, but it might also help you get rid of some that actually do.

That last statement might surprise you, particularly if you’ve heard the credit bureau company line that you can’t legally remove true, negative information from your credit report. I admit that I used to parrot that line myself, usually when trying to warn people away from the many scam artists who promise to erase all the bad information on your credit report in exchange for a fat fee.

I’ve since learned that sometimes—not always, but sometimes—you can get accurate information removed from your file, especially if it has to do with an old collection account.

Now, the bureaus and Fair Isaac will tell you that this isn’t “playing fair”—that the integrity of the credit system depends on credit reports reflecting the most complete picture possible, including all available negative and positive information.

Unfortunately, the bureaus are still allowing far too much erroneous data to seep into their system, and that’s hurting consumers. The credit-reporting process is still weighted heavily in favor of lenders and collectors.

That steams Jim Stephenson, a realtor in Branson, Missouri, who has watched several of his clients struggle with inaccurate credit information:

“If I’m a subscriber [to the credit bureaus], all I need is your Social Security number and I can tell them anything derogatory about you I want. Without question or hesitation, this info goes onto your credit file. It can be extremely difficult to prove a negative. How do you prove that you don’t owe me money?” Jim wrote. “Time and again I have witnessed firsthand the inability of a client to have misinformation that is irrefutably not my client’s debt removed without a protracted and costly fight. Why is this? It’s because the burden of proof is on the accused, not the accuser.”

The issue of re-aging can be particularly troublesome. The seven-year limit on reporting most negative items was designed to give consumers some protection against relentless creditors. In effect, lawmakers were trying to prevent collection agencies from creating a sort of perpetual debtors’ prison for people who had made mistakes. Congress even strengthened the law in the mid-1990s to prevent collectors from endlessly extending the seven-year time period just by passing an account from one agency to the next (as Beth’s collection agency was threatening to do). Instead of using the “date of last activity,” as was common before 1997, the seven-year clock now starts 180 days after the account first became delinquent.

To get around the limit, some collection agencies are now simply flouting the law and pretending an old debt is a new one. I’ve received numerous letters from consumers who had long-forgotten delinquent accounts suddenly pop back up on their credit reports with a new and phony date. One of the largest collection agencies, NCO Financial Systems, agreed in early 2004 to settle a lawsuit with a group of borrowers over this issue.

Unfortunately, the type of collector that would actually post false information to a credit bureau file might not be the type that will back down in the face of a validation demand or a credit bureau investigation. You’ll still need to make the validation demand, of course, and follow up with a credit bureau dispute if you don’t get the response you want. But it might take a lawsuit to get the falsely incriminating information out of your file.

There’s another issue. Plenty of consumers are like Beth and Dave in Chapter 6, “Coping with a Credit Crisis,” in that they let spats with merchants get out of hand and wind up with collections on their reports. These collections—even for relatively small amounts—can have an outsized effect on a credit score. The thinner or younger your credit file, the worse a collection can hurt. Although mortgage lenders tend to ignore these small accounts, credit-scoring formulas might not. Getting rid of collections can create a more accurate picture of your credit habits.

It’s also not uncommon to have two, three, or even more collection accounts reported for the same debt. That amplifies the damage to your credit score and reflects the collection industry’s practice of selling and reselling the same debt to different companies. Weeding out some of these extraneous collection accounts provides a more accurate picture of your credit situation.

Besides, I’m going to assume that if you care enough about your credit to read this book and spend the time necessary to clean up your credit report, you’re demonstrating the kind of dedication and responsibility that should make you a good credit risk in the future.

You shouldn’t assume, however, that you can get every piece of negative information removed—far from it. The more recent the negative mark, the less likely you’ll get it to budge. Your chances of success will improve as the “sin” gets older.

You also have no guarantee that getting rid of a collection action will help your score much, if at all. The scoring formula generally weighs what the original creditor had to say about you more heavily than what any subsequent collector reports. In other words, delinquencies and charge-offs reported by the original creditor can still hurt your score even if the subsequent collections disappear.

Okay, that’s enough background. If you’re trying to get rid of a collection action, credit repair veterans suggest first disputing it as “not mine,” rather than starting off with a validation demand.

Sometimes, the collection agency simply won’t bother to verify the account, particularly if it’s old or small. If that’s the case, the collection will be dropped from your report—no muss, no fuss.

If the credit bureau verifies the account, go directly to the collection agency and demand validation. You can find sample letters at Web sites such as CreditBoards.com or CreditInfoCenter.com. Essentially, you need to tell the collection agency that under the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, it must prove that you owe this debt. Demand copies of documents such as the signed account agreement that created the debt and the agreement with the original creditor that gives the agency the right to try to collect the debt.

If the collector fails to respond or can’t provide sufficient evidence that you owe the debt, it’s supposed to remove the collection from your report. If that doesn’t happen, you can bring the matter to the attention of the credit bureaus and ask for an investigation. Make sure you make it clear to the bureaus that this is not a repeat of your earlier request; provide the evidence that you asked for validation, and let them know that the collector didn’t comply.

If the account doesn’t disappear at this point, you have both the bureaus and the collection agency on the hook for credit-reporting violations and potentially could pursue a lawsuit.

What You Need to Know About Statutes of Limitations

Before we go any further down this path, however, you need to know about one more factor that will affect your credit repair efforts: statutes of limitations.

You already know that credit bureaus have a limited time (seven to ten years) in which they can report negative information. The statutes of limitations I’m talking about, however, curb the amount of time that a creditor can sue you over a debt.

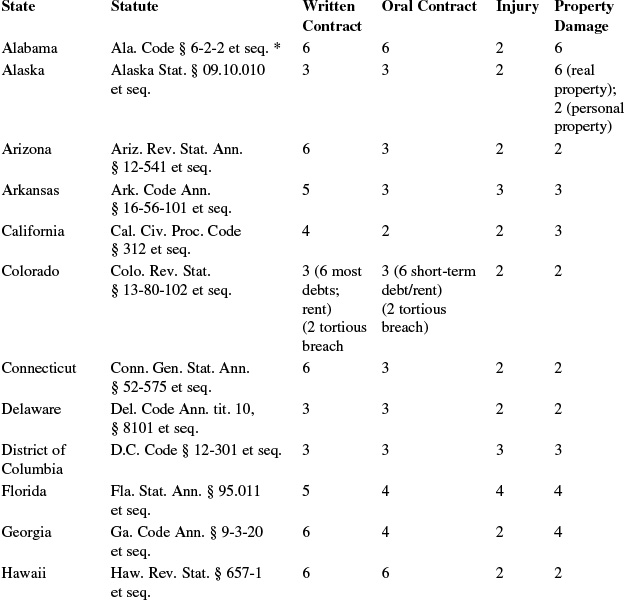

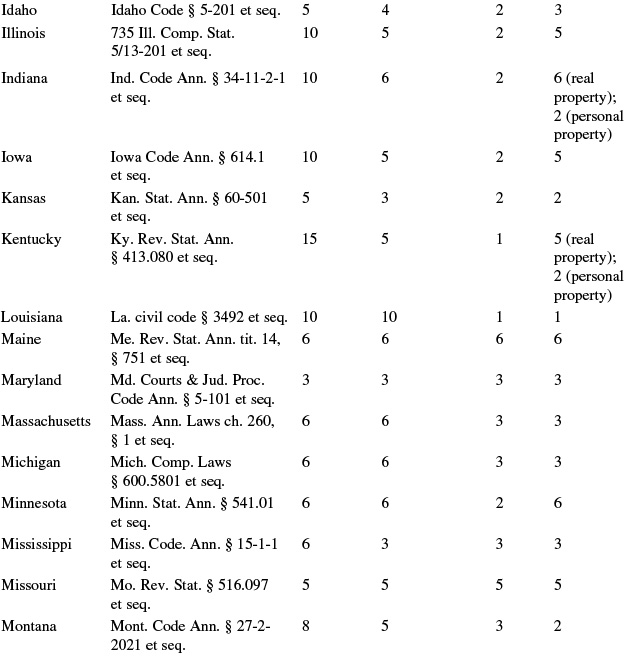

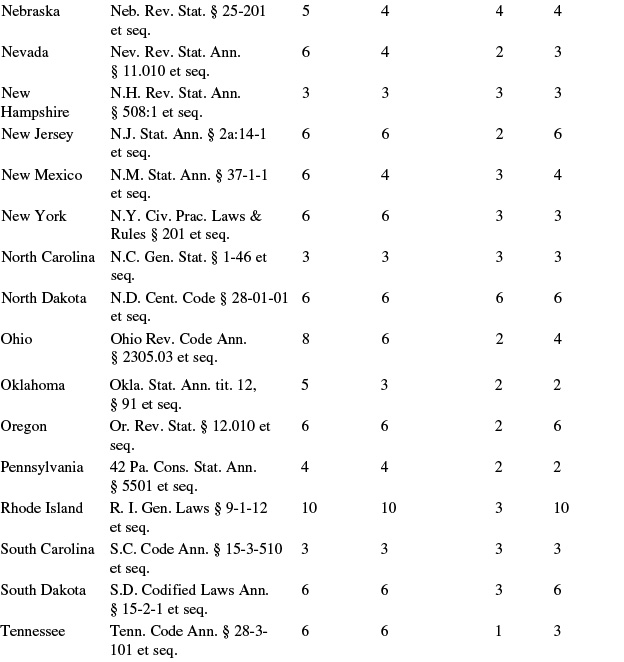

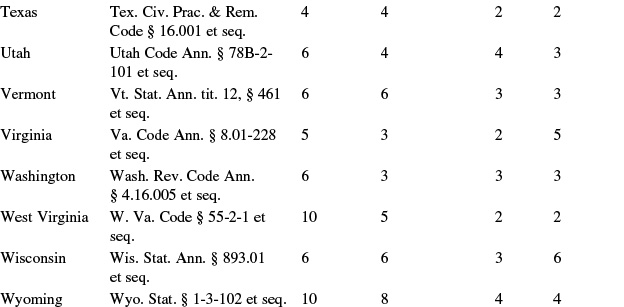

Statutes of limitations vary widely by state and might depend on the type of debt involved. In Alaska, for example, creditors can’t sue you after 3 years have passed since the delinquency. In Kentucky, the statute is 15 years for written contracts, and 5 for oral contracts. Depending on the state, open-ended contracts—such as credit cards—might be considered a written contract, an oral contract, or have a different statute of limitations altogether.

Statutes of Limitations for the 50 States (and the District of Columbia)

Source: Nolo.com.

That’s not the end of the complexities and vagaries. What if you incurred the debt in one state but now live in another? Typically, the creditor or collector can choose to use the state with the longer statute.

Also, you can restart an expired statute of limitations in some states by making a payment on an old debt, or just by acknowledging that you owe the money.

Now, you don’t have to worry about any of this if the item you’re trying to get deleted is a paid collection and is listed that way on your credit report. If it’s an unpaid collection, or any unpaid account for that matter, you’ll want to do some legal research to make sure that you understand the statutes that apply in your situation:

• If a debt is still within the statute of limitations and it’s actually your debt, you want to be careful about disputing the information with the credit bureaus. Remember the phrase, “Let sleeping dogs lie?” You could reawaken interest in collecting the debt by drawing it to the creditor’s attention. If you’re not prepared to pay the debt or get sued and suffer the potential ding to your credit score that either action could evoke, the better course might be to leave the debt alone and hope it slides silently off your credit report in a few years. (See the next section “Should You Pay Old Debts?” for more details.)

• If the statute of limitations is well past, you can be more aggressive in trying to get an old debt off your report. If you choose this course, though, make sure you don’t do anything that could start the statute of limitations all over again.

If you’re unwilling to handle all this yourself—and it is a lot to expect a layperson to do—a few good law firms handle cases like this. Use the National Association of Consumer Advocates to get a referral, though, and steer clear of any law firm or other outfit that guarantees results or demands enormous fees in advance.

Should You Pay Old Debts?

Legally, you owe a debt until it’s paid, settled, or wiped out in bankruptcy.

Some people erroneously believe that their obligation ends when a creditor charges off the debt. But a charge-off is essentially just an accounting term. The creditor can continue trying to collect or sell the debt to a collection agency, which can try to get you to pay.

Your obligation to pay doesn’t end when an unpaid debt falls off your credit report after seven years. The creditor might not be allowed to report the account, but collection actions can continue.

Similarly, your state’s statutes of limitations define how long a creditor or collection agency can take you to court over a debt. But even if you can’t be sued, a creditor or collector can still ask you to pay.

Given all that, shouldn’t you just pay what you owe if you possibly can?

Many people would say yes, pointing out that we have a moral obligation to pay the debts we incur. But the answer to this question is actually trickier than it might appear, for several reasons.

Paying Old Debts Might or Might Not Hurt Your Credit Score

For years, a quirk in the credit-reporting process meant that paying old debts could actually hurt your credit. When the creditor or collection agency updated your credit report to reflect the payment, the FICO formula was often fooled into thinking the old, troubled account was newer than it actually was. Because the formula is designed to weigh recent behavior—good and bad—more heavily than past behavior, anything that looked like you had incurred recent problems could really hurt.

Fair Isaac worked with the credit bureaus to fix this problem. The issue can still pop up, though, if your lender is using an old version of the FICO formula to compute scores. Fair Isaac spokesman Craig Watts said the company doesn’t know how many lenders use the old versions, but he thinks it’s a “very small percentage” of the total. Still, it’s possible that paying old debts could hurt you in the eyes of some creditors.

Just Contacting an Old Creditor Can Leave You Vulnerable to a Lawsuit

Each state has different guidelines on how long a creditor can sue you over a debt, but some states have provisions that allow this statute of limitations to be extended if you make a payment on an old debt or even acknowledge that you owe it. You could be making a good-faith effort to pay your bill or be talked into making a “token” payment as part of negotiations with a collection agency, and the creditor could use that as an excuse to haul you into court and get a judgment against you—an action that might not have been permitted if you had just left the debt unacknowledged and unpaid. The judgment would be a new and serious black mark on your file that could be reported for another seven years.

You’re Often Not Dealing with the Original Creditor

The company that you owe the money to might have long since cleared the debt off its books, taken a tax write-off for the loss, and sold the debt—usually for pennies on the dollar—to a collection agency. The original creditor might not accept money if you tried to offer it but would instead direct you to the collector. Many people understandably feel less obligated to a collection agency that bought their debts for a tiny fraction of face value than they do to the company that originally extended the credit.

You Might Be Exposing Yourself to Some Pretty Nasty Characters

Despite laws designed to curb them, some collection agencies employ people who lie to, harass, and abuse borrowers. They might scream at you, use obscene language, or threaten you with jail time. (All these actions are, of course, illegal, but if you don’t believe they happen, you need to take a look at my mailbag.)

Even if collectors are polite to your face, they might do things behind your back to further endanger your financial life. Collectors might promise to drop a harmful remark from your credit file and then not follow through—or make the black mark even worse. They might arrange a deal that they say will settle your debt, and then sell the unpaid portion to another agency that renews collection activity. Or they might report any debt you didn’t pay to the IRS, which can tax the so-called forgiven debt as income.

More than a few collectors feel that anything they do is justified because—don’t you know?—debtors are bad people. Collectors have written me insisting that debtors are actually thieves and deserve what they get. The fact that owing money is usually not illegal—but that violating fair credit-reporting and collecting laws is—remains a distinction that completely escapes them.

Problems with collection agencies are so rampant that the FTC typically has more complaints about that industry than any other. The only category that generates more complaints is identity theft. Debt collection accounts for more than one out of ten grievances filed with the agency.

You might still decide to brave all this and try to pay off an old debt. You might feel a strong moral obligation to do so, regardless of the potential consequences. Or you might need to settle a debt because you want to get a mortgage sometime soon. (Lenders typically won’t give you a home loan with an open collection on your report.)

If you decide to proceed, make sure you’ve done your research on the statutes of limitations that apply. (It’s tricky, but you can conduct an entire settlement negotiation with a collector without ever acknowledging that you owe the debt—and most attorneys would recommend that’s exactly what you should try to do.)

If you can possibly deal with the original creditor, rather than a collection agency, try to do so. Try to get the original creditor to report your account as positively as possible in exchange for your payment. Having the account reported “paid as agreed” would be good. Having the account reported as “settled,” however, could leave your score worse off than if you’d left the account open and unpaid. Some credit-repair veterans have had luck getting the creditor to stop reporting the troubled account altogether in exchange for payment, which could be great for your score, although the bureaus strongly discourage this.

If you’re dealing with a collection agency, though, push hard to have the entire account deleted. You will have the most leverage if you can make a lump-sum payment, rather than having to make payments. Remember: Any updating that the collection agency does—even if it’s to report that you’ve paid your debt—can make the black mark appear more recent than it is and hurt your score.

If, however, you decide that the cost of paying old bills is greater than the payoff—well, you wouldn’t be the first. Some people just decide to donate to their favorite charity an amount equal to the unpaid debt and call it a day.

“But You’ve Got the Wrong Guy!”

It’s not uncommon for debts that you don’t owe to pop up on your credit report. Thanks to identity theft, credit bureau mistakes, and greedy collection firms, this happens way too often for comfort.

And you might find yourself truly on the hook for a debt you didn’t personally incur.

How can that happen? Here are two of the most common ways:

• You cosigned a loan for someone else—If that person doesn’t pay, you’re legally obligated to foot the bill, and any delinquencies, charge-offs, or collection actions related to the debt will be reported on your credit file. The creditor isn’t even required to notify you if the other borrower defaults. The first time you find out about it might well be when it pops up on your credit report.

• It’s a joint account, even if you have since divorced the other account holder—This one gets people all the time. It doesn’t matter what your divorce decree says about who was supposed to pay what. If it’s a joint account, it’s a joint debt. Your ex can easily trash your report by not paying a joint credit card or mortgage. That’s why it’s so important to close joint accounts and refinance mortgages and other loans before a divorce is final. I go into more detail in Chapter 12, “Keeping Your Score Healthy.”

What if you’re just an authorized—rather than a joint—user on someone else’s account, and that person’s negative information is showing up on your report? If the person added you to the account after opening it and didn’t use your income and credit information in the original application, you should dispute the information with the credit bureaus, pointing out that you’re not responsible for the debt. You also should ask the original account holder to have your name removed from the account.

If the person used your information and forged your signature to qualify, however, you might need to file a police report to get the creditors to eliminate the information. See Chapter 8, “Identity Theft and Your Credit,” for more details.

Part II: Adding Positive Information to Your File

There’s more to credit repair than just getting rid of the negative information. You need to ensure that any positive information that can be included in your file actually is.

Try to Get Positive Accounts Reported

You know that the credit bureaus typically don’t share information, but it can be frustrating if one of your good, paid-on-time accounts doesn’t show up on all your credit reports.

What’s worse is when a credit account isn’t reported at all. Some creditors simply don’t bother to use credit bureau services, and others—usually subprime lenders—deliberately hide the histories of their best customers for fear that their competitors will swoop in.

Although you can’t force a creditor to report an account to a bureau or report more frequently, you can always ask.

Sometimes it’s all but impossible to get your on-time payments recorded. Most landlords, utility companies, and phone companies will report you to the credit bureaus only if you screw up. (So be sure you don’t screw up.)

Borrow Someone Else’s History

No, I’m not suggesting that you commit identity theft. Being added to someone else’s credit card account as an authorized user can instantly improve your credit report if that person’s credit is in good shape. (The opposite can also happen, so make sure you pick the right person.) A cooperative credit issuer exports the card user’s account history into your report so that you can benefit from the other person’s good financial habits. Not all credit issuers do this export, though, so it’s important to call first and ask.

There’s another plus to being an authorized, rather than a joint, user: You’re not liable for any debt the original account holder runs up.

Get Some Credit or Charge Cards if You Don’t Have Any

You need to actively use some plastic to rebuild your score. Although it’s anybody’s guess how many cards are optimal, it’s a safe bet that you’ll eventually need more than one.

If you still have accounts you can use, that’s great. If your accounts have been closed, you’ll need to start from scratch. The plan is outlined in the following sections.

Apply for a Secured Card

Secured cards give you a credit limit that’s generally equal to the deposit that you make. You want a card that reports to all three credit bureaus, doesn’t charge an application fee or outrageous annual fees, and converts to a regular, unsecured card after 12 months or so of on-time payments. Bankrate.com, CardRatings.com, CreditCards.com, LowCards.com, and NerdWallet, among others, have whole sections on secured cards, including current information about which bank is offering what.

Get Department Store and Gas Cards

These cards tend to be the easiest unsecured plastic you can obtain. After you’ve had your secured card for a few months, apply for one of these—and perhaps a second one about six months later. Don’t rush this process, because applying for too much credit in too short a time period can hurt your score.

Get an Installment Loan

You might take out a small, personal loan from your bank or credit bureau and pay it back over time. Or you might, as our friend Chance did, simply “suck it up” and go for a high-rate auto loan:

“My first vehicle loan out of BK was at 21 percent interest. After paying this for about two years, I traded it in and purchased another,” Chance wrote. “The next [loan rate was] at 13.99 percent. [I paid] this for a year [and] then refinanced online for 7.95 percent. Then [I] traded it in, and now I have a 6 percent auto loan.”

I can’t advise buying three cars in five years like Chance did. But you should try to make sure you’re not tying yourself to a long-term loan at usurious rates. Get a shorter loan, if you possibly can, and make a decent down payment to make sure you have some equity in the vehicle so that you can refinance it when your credit improves.

Consider a Cosigner

If you can’t get a loan on your own, you can try to find a cosigner to facilitate the deal. But realize that person is putting his credit history on the line for you. If you mess up, your cosigner pays the price because he’s just as legally obligated to pay the debt as you are.

Make Sure Your Credit Limits Are Correct

This is a point that many credit rebuilders unfortunately overlook. A big chunk of your credit score has to do with how much of your available credit you’re using. If the credit limits are showing up on your report as lower than they actually are, your debt utilization ratio will be higher than it needs to be. You can use the dispute process, but it might be just as expeditious to call your creditors and ask them to update your credit bureau files.

Part III: Use Your Credit Well

You might want to review the information in Chapter 4 on improving your score the right way. When you’re rebuilding after a disaster, you need to be particularly careful about what’s discussed in this section.

Pay Bills on Time

Remember: The biggest chunk of your credit score is likely to be your payment history, and even one late payment can be devastating. Become religious about making sure all your bills are paid on time, all the time.

If you get an installment loan, set up an automatic payment system—either direct withdrawals from your checking account or automatic, recurring payments through an online bill paying system. Leave nothing to chance.

Use the Credit You Have

Make a few small purchases every month with your plastic—but no more than you can pay off each month. If you worry that you’ll give in to temptation if you carry your card with you, arrange to have some small monthly bill, such as an online game subscription or health club dues, charged to the card each month. Then set up an automatic payment from your checking account. That way the card is being used and the bill is being paid without your having to think about it.

Keep Your Balances Low

Somebody who has good credit can occasionally afford to run up a big balance on a credit card. That’s not you. It doesn’t matter if your credit limits on your new cards are ridiculously low. You never want to use more than about 30 percent of the limits you have; 20 percent or less is better, and 10 percent or less is best. If you go over 30 percent, try to make a payment before the statement closes to reduce the balance that’s reported to the credit bureaus.

You can keep track of your purchases in a checkbook register, or just check your balances frequently at the card’s Web site. Quicken or Mint personal finance software can also help you monitor your balances.

Remember: These cards are not for your convenience—and they certainly shouldn’t be an excuse for you to carry debt. The plastic you have now is meant to help rehabilitate your beaten-up credit.

Pace Yourself

It’s never a good idea to apply for a bunch of new credit in a short period of time. That’s particularly true when you’re trying to rebuild a score. It’s not a bad idea to wait at least six months between applications for credit. Don’t apply for cards just to see whether you’ll be accepted, and do try to target your applications to lenders that are likely to want your business. A recently bankrupted person who applies for a low-rate card from a major issuer is just asking to get turned down—and have another ding added to her file.

Don’t Commit the Biggest Credit-Repair Mistakes

You can see from the information in this chapter that fixing your credit can be a long and involved process, with many opportunities for the novice to make a mistake. Three of the biggest mistakes you should avoid are spelled out here.

Hiring a Fly-by-Night Firm

The Federal Trade Commission is constantly trying to stamp out scam artists promising instant credit repair, but like cockroaches, they always return. You can pretty much assume a scam if the company guarantees its results in advance, wants to charge you a big, upfront fee, or suggests you create a “new” credit report by using a different Social Security or taxpayer identification number.

Most people can handle their own credit repair without paying big fees or committing fraud. If you run into problems, look for a legitimate law firm through the National Association of Consumer Advocates at www.naca.net for help.

Failing to Get It All in Writing

The phone is not your friend. Although you can and should take copious notes if you ever have to have a phone conversation with a creditor, collector, or credit bureau, you’re much better off conducting credit repair in writing.

Reviving the Statute of Limitations

States have differing rules about how long a creditor can sue you over a debt, with most limiting the period to three to six years. Making a payment on an old debt, or even acknowledging that you owe it, can revive that statute and leave you vulnerable to a lawsuit. Make sure you know the rules for your state when dealing with old debts.