4

Broadcast Programming

This chapter treats the programming of radio and television stations and examines the

• role of the program department and the responsibilities of the program manager and other departmental staff

• types and sources of broadcast programs, and the strategies employed to air them with maximum effect

• major differences between programming a television station affiliated with one of the three original networks and programming an affiliate of another network or an independent station

Commercial radio and television stations air thousands of hours of programs each year. Individual programs may be produced by the station itself or obtained from another source. They may be designed chiefly to entertain, inform, or educate. They may be sponsored or sustaining. They may attract audiences numbering a few hundred or many thousands.

Despite the differences, the programming of all stations is determined by four influences:

• The audience, which seeks out a station for its programs. Listeners or viewers may be exposed to other content, such as commercials and public service and promotional announcements, but their principal goal is to hear or view program content that satisfies their need at a particular time. Programs that fail to attract listeners or viewers, or fail to satisfy their needs, are imperiled. So are the financial fortunes of the station.

• The broadcaster, who is responsible for operating the station profitably for its owners. The greater the audience, the greater the likelihood that a profit can be realized. Accordingly, the broadcaster selects and schedules programs to attract as many people as possible among the targeted audience.

• The advertiser, whose principal interest in using a radio or television station is to bring a product or service to the attention of those most likely to use it. Programs that attract potential customers stand the best chance of attracting advertising dollars, especially if the number of people is large and the cost of delivering the commercial to them is competitive.

• The regulator, or government and several of its agencies, notably the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). Its goal is to ensure that the station is operated in a way that serves the public interest. Since passage of the Radio Act of 1927, the regulator has taken actions aimed at compelling or encouraging broadcasters to engage in certain programming practices to satisfy that goal.

Much is said and written about broadcast programming. However, it would be unwise to identify any one influence for praise or condemnation. The programming we hear and see results from the interaction of all four forces. In this chapter, we shall consider the audience and the broadcaster. The advertiser and the regulator will be treated later.

THE AUDIENCE

More than 98 percent of U.S. households have radio and television receivers. The programs they carry attract males and females of all ages and from all socioeconomic categories and ethnic groups.

The pervasiveness and appeal of radio are indicated by the following facts:

• radio reaches more than 94 percent of persons aged 12 and over each week1

• four out of five adults are reached by car radio each week2

• the average listener spends almost 20 hours per week listening to radio3

The reach of television and the extent of its use are no less significant:

• 79 percent of U.S. households own two or more receivers

• television is the main news source for more than 75 percent of the U.S. public

• the average household views about eight hours daily4

The size and composition of the audience for the two media fluctuate. The weekday radio listenership peaks at 7:00 A.M. It holds fairly steady from 9:00 A.M. to 4:00 P.M., then begins to drop. On weekends, listenership is at its highest between 9:00 A.M. and 3:00 P.M.5 Men listen more than women, with men aged 35 to 44 listening most. They are followed by men 45 to 49 and 50 to 54.6

The television audience grows throughout the day and reaches a peak between 9:00 and 9:30 P.M. (ET). People spend more time viewing during the winter than the summer. Sunday evening attracts the largest number of viewers, and Friday evening the smallest.7 Women watch TV more than men, and older men and women more than younger adults. Teenagers and children aged 2 to 11 watch least.8 Larger households and those with children view more than smaller households and those without children. There is more use of television in pay-cable households than in those with basic cable or no cable at all. Differences among income classifications are not great, but households with an annual income of less than $30,000 view more than those with income exceeding that amount.9

THE PROGRAM DEPARTMENT

Of all the factors that determine the financial success of a radio or television station, none is more important than programming. It is programming that brings listeners or viewers to the station. If the number of listeners or viewers is large, and if they possess the characteristics sought by advertisers, the station will attract advertising dollars. Accordingly, the station’s revenues and potential profits are influenced largely by its programming. Responsibility for programming is entrusted to a program department.

Functions

The major functions of the program department are

• the planning and selection of program content that will appeal to targeted audiences

• the acquisition or, for non-news content, the production of programs

• the scheduling of programs

• the monitoring of programs to ensure compliance with the station’s standards and regulatory and legal requirements

Organization

The program department is headed by a program manager or program director, who reports directly to the general manager. In some stations, programming and production are combined in one department under an operations manager.

The number of people who report to the program manager, their titles, and their responsibilities vary. In addition, the titles and responsibilities of the program personnel in a radio station differ from those in a television station. We shall examine the two media separately.

Radio

The program department staff in a radio station with a music format generally includes the following:

Music Director

The music director is responsible for

• additions to, and deletions from, the station’s playlist of music

• preparation of the playlist and supervision of its execution

• auditioning of new recordings

• consultation with the program manager on music rotation

• liaison with representatives of recording companies to obtain new releases

• contact with music stores on sales of compact discs

• cataloguing and filing of compact discs (in large markets, this responsibility may be handled by a music librarian)

• in small markets, an air shift and some local production

Announcers

Announcers frequently are called disc jockeys or deejays. Their major responsibility is an air shift, which includes

• introduction of recordings and programs

• reading of live commercials and promotional, public service, and station identification announcements

• delivery of time and weather checks and traffic reports

• operation of control room equipment

In addition, announcers may

• produce commercials and other announcements

• serve as talent for commercials and other announcements

• double as music director or production director

In many stations, continuity or creative services and traffic staff report to the sales manager. In others, their activities are supervised jointly by the program manager and the head of the sales department. Continuity writers often are responsible for a variety of copy, including commercials and public service and promotional announcements. They also check copy for compliance with the station’s program and advertising standards. Traffic personnel place on the schedule details of all program and commercial content to be aired.

At news-format stations, the program manager is, in essence, a news director. The staff consists of editors, anchors, reporters, writers, and desk assistants.

The staff of news/talk stations comprises personnel responsible for news, such as anchors and reporters, and for talk, including producers, hosts, and telephone screeners.

Television

In many television stations, the program “department” may consist of only a program director (PD), whose major responsibility is the development of program schedules. As noted later, the PD also works with the general manager and others on the acquisition of syndicated programs.

THE PROGRAM MANAGER

Responsibilities

Program managers in small and medium markets are involved in a broader range of activities than their counterparts in large markets. Obviously, there are differences between programming a radio station and a television station. In addition, in television, the amount of time spent on programming responsibilities is influenced greatly by the station’s status as a network affiliate or independent. However, all program managers engage in four basic tasks: the planning, acquisition, execution, and control of programs.

Program Planning

Program planning involves the development of short-, medium-, and long-range plans to permit the station to attain its programming and financial objectives.

As we shall see later in the chapter, the principal focus in radio is on the selection of a format and other program content to attract and satisfy the needs of particular demographics. Planning also includes the hiring of announcers or hosts whose personality and style are compatible with the station’s format.

In television, planning is directed toward the selection and scheduling of programs to appeal to the largest number of people among the available audience. Affiliated stations also must consider which network programs they will broadcast and which they will reject or delay.

Since programming is the essential ingredient in attracting audiences, and since some audiences are sought more than others by advertisers, planning usually is done by the program manager in consultation with the head of the sales department and the general manager.

Program Acquisition

The program manager implements program plans by having programs produced by the station itself or by obtaining them from other sources. The major sources of radio and television programs are described later in the chapter. Again, the head of the sales department and the general manager are involved.

Program Execution

Execution involves the airing of programs in accordance with the plans. The strategies of both radio and television program execution are described later.

The program manager coordinates the scheduling of content with traffic personnel, and its promotion with the promotion and marketing director.

Program Control

The program manager often is called the “protector” of the station’s license because of the responsibility for ensuring that the station’s programming complies with the terms of its license.

As protector, the program manager

• develops the station’s program standards

• supervises all program content for adherence to the station’s standards, the FCC’s Rules and Regulations, and other applicable regulations and laws

• maintains records of programs broadcasted

The program manager also controls

• the direction and supervision of departmental staff and their activities

• the station’s compliance with certain contracts, such as those with a network, program suppliers, and music licensing organizations

• program costs, to ensure that they do not exceed budgeted amounts

Qualities

The program manager should be knowledgeable and should possess administrative and professional skills and certain personal qualities.

Knowledge

The program manager should have knowledge of

• Station ownership and management: Their goals and the role of programming in achieving them.

• The station and staff: Programming strengths and shortcomings, the relationship of the program department to other station departments, and the skills and limitations of departmental employees.

• The market: Its size, demographic composition, economy, and the work and leisure patterns of the population as a whole and its various demographic groups; the community’s problems and needs; for radio, the music and information tastes of the community and, for television, program preferences.

• The competition: Current programming of competing stations, their successes and failures, and their program plans.

• Program management: The duties of the program manager and how to discharge them. This includes knowledge of the sources and availability of program content; production process and costs; salability of programming and methods of projecting revenues and expenses; sources and uses of program and audience research; programming trends and developments in broadcast technology; laws and regulations pertaining to programming.

• Content and audiences: Formats, programs, and other content; their demographic appeal; and the listening or viewing practices of the audience.

Skills

The program manager must possess administrative and professional skills, among them the ability to

• develop program plans through consideration of need, alternative strategies, and budget

• evaluate ideas for local programming and coordinate the activities of staff responsible for program production

• analyze and interpret ratings and other audience research, and assess the potential for the success of locally produced programs and those available from other sources

• select and schedule content to maximize availability and appeal to targeted demographics

• negotiate contracts with program suppliers, freelance talent, music licensing organizations, and others

Personal Qualities

Audiences and station staff have strong feelings about the programming of radio and television stations and are not hesitant to express them. Accordingly, the program manager must be

• patient in listening to various, often contradictory, viewpoints offered by telephone, letter, fax, or E-mail from listeners or viewers and community groups, and in meetings with colleagues

• understanding of the needs and interests of audience members and of the motivations of fellow employees

• flexible in adapting to changing public tastes and programming and technological trends

• creative in developing and executing program and promotion ideas

• ethical in dealings with others in and outside the station and in programming practices

Influences

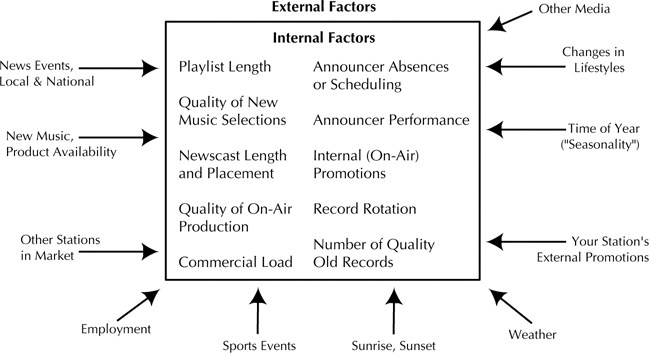

The program manager’s decisions and actions are influenced by many factors. A model developed by The Arbitron Company (Figure 4.1) identifies 21 factors that comprise the decision-making environment in a radio station with a music format. Obviously, the station can control all the internal factors listed, such as the performance of announcers, the quality of on-air production, and the music rotation. However, only one of the external factors—external station promotions—is within the station’s control. The station has no control over such influences as the availability of new music in its format, the activities of competing stations or other media, and changing lifestyles that may affect audience habits and tastes.

Figure 4.1 Music-format decision-making environment.

(Source: The Arbitron Company. Reprinted with permission.)

J. David Lewis used responses from 301 stations in the United States to determine influences in television station programming. He developed eight categories, in no particular order of priority:

• direct feedback from the audience, including letters, telephone calls, and conversations

• regulatory, or rules and standards of practice, such as commitments to the FCC, its rules and regulations, and the station’s own policy statement

• inferential feedback, or ratings

• conditional, a mix of factors including comments of critics and opinions of friends outside the station

• production staff, the opinions of station personnel with production responsibilities

• personal or subjective judgment, including instinct, common sense, and knowledge of the community

• financial, or factors related to the station’s income and expenditures, such as sales potential, sales manager’s opinion, and cost

• tactical, that is, methods of program planning, the arrangement of the schedule, and viewing trends10

RADIO STATION PROGRAMMING

The programming of most radio stations is dominated by one principal content element or sound, known as a format. It is designed to appeal to a particular subgroup of the population, usually identified by age, socioeconomic characteristics, or ethnicity.

In reality, few listeners probably know or care what name is used to describe the format of their favorite station. However, the selection of a name is important to management and the sales staff in projecting the station’s image and in positioning the station for advertisers.

Formats

There are dozens of formats, but all can be placed in one of the following categories: music, information, and specialty.

Music

The music format is the most common among commercial radio stations. Describing the format of a particular station in one or two words has become increasingly difficult with the fragmentation of formats and the appeal of some artists in more than one format. In addition, stations use different names to characterize similar sounds. Arbitron identifies the following as America’s favorite music formats:11

Adult Contemporary (AC)

AC and its variants—soft/light AC, hot AC, mainstream AC, full-service AC, and adult rock—have a basic format that consists of well-known rock hits and pop standards. Women constitute about two-thirds of the formats’ audience. More than half of all listeners are aged 25 to 49.

Adult Standards

Characterized by pre-rock era music, this classification includes easy listening, middle-of-the-road, nostalgia, and variety. Half the listeners are 65 and older. No other format has such a large share of its audience in a single age group.

Alternative

The format includes stations identifying themselves as album alternative and new rock. Men account for almost two-thirds of the audience, nearly 85 percent of which is made up of persons aged 44 or younger.

Classical

This format consists chiefly of recorded classical music and live performances of symphonies, opera, and chamber music. Many stations program short music selections during the day and concerts in the evening. Its greatest appeal is to middle-aged (35–54) and older (55+) listeners, who constitute 90 percent of the audience. It attracts more college graduates (64 percent) than any other format. Listeners are relatively affluent, also, with 40 percent earning more than $75,000 a year.

Contemporary Hit Radio (CHR)

This format includes stations specializing in pop CHR and rhythmic CHR. Basically, the format is characterized by a tightly controlled playlist of top-selling rock singles, selected new recordings that are on their way up, and occasional oldies. It attracts the largest share of teens (26 percent) of all formats. About three-quarters of the audience are 34 or younger.

Country

This format embraces both traditional and modern country music. The format has broad appeal to men and women in all age ranges. However, those aged 35 to 44 are the most frequent listeners.

New AC/Smooth Jazz

This format includes jazz, new age, and new adult contemporary formats. The format consists of instrumentals, with some compatible vocals. Adults aged 35 and over make up the core audience.

Oldies

The focus is on rock-era oldies and includes 1970s hits and rhythmic oldies. The format appeals equally to men and women and draws more than half its audience from those aged 35 to 54.

Rock

This format is rock-based music from the mid-1970s to the present, including album rock and classic rock. The music has huge appeal to men. They constitute more than 70 percent of the audience, the largest adult male share of any format. Adults aged 25 to 44 make up more than half the listenership.

Urban

This format includes urban AC and urban oldies. The basic format specializes in contemporary rhythm and blues music. African Americans make up more than 80 percent of the audience. Listeners tend to be young—about one-third are aged 12 to 24.

While music is the dominant element in music-format stations, a variety of other program content is aired. The kind, amount, and frequency of such content are determined by a number of factors, such as format, the composition of the audience, and the size and location of the community. Examples of nonmusic content include

• Community bulletin board: Information on community events.

• Editorials: The opinions of the station’s ownership on local or national issues and events.

• Features: Stories on a wide range of topics of interest to the station’s listeners.

• Market reports: Both agricultural and business reports.

• News: Local, regional, national, and international news.

• Public affairs: Generally interview programs on local or national issues and events.

• Public service announcements: Announcements for government and nonprofit organizations.

• Religion: Services of various religious denominations or discussions on religion.

• Sports: Scores, reports, and play-by-play.

• Traffic reports: Local traffic conditions, especially in large communities and most frequently in drive times.

• Weather reports: Local and regional conditions and forecasts, but more extensive in times of weather emergencies.

Information

There are two basic information formats, all news and all talk. A third consists of a combination of the two, and is called news/talk. Some stations restrict their news and talk content to sports and combine it with live coverage of sporting events in an all-sports format.

All News

The all-news format consists of news (local, regional, national, and international), information and service features, analysis, commentary, and editorials. It appeals mostly to adults aged 35+, especially bettereducated males.

Stations assume that the audience will tune in only for short periods of time to catch up on the latest developments. Accordingly, they program the format in cycles of 20 or 30 minutes, with frequent repetition of the top stories. This characteristic often is used in promotion, with slogans such as “Give us 20 minutes and we’ll give you the world.”

The format requires a large staff of anchors, writers, reporters, editors, desk assistants, and stringers, as well as mobile units and numerous news services. As a result, it is expensive and tends to be successful financially only in large markets.

All Talk

Interviews and audience call-ins form the basis of the all-talk format. The subject matter varies greatly. Interview guests may generate discussion of their personal or professional lives. A call-in may focus on a timely or controversial topic. Many stations have hosts with expertise as psychologists, marriage counselors, and sex therapists, and callers use the program to expound on their personal problems.

Adults aged 35 to 65+ are the most consistent listeners. Most often, they are persons in search of companionship or a forum for their views.12

Each hour or daypart is programmed to appeal to key available demographics. Success is tied closely to the skills of the host, who must be knowledgeable on a wide range of topics, easy in conversation, and perceptive. Good judgment and the ability to maintain control of the conversation are other desirable attributes.

The format also requires producers who have a keen awareness of local and national issues, and the ability to schedule guests who are informed, eloquent, and provocative. Screeners are used to rank incoming calls for relevance and to screen out crank calls.

News/Talk

This combination of the all-news and all-talk formats takes different forms. Typically, it consists of news in morning and afternoon drive times, with talk during the remainder of the broadcast day. Some stations air play-by-play sports on evenings and weekends. The format’s chief demographic appeal is to persons aged 35 to 65+.

Specialty

There are many specialty formats. However, the following are the most common:

Ethnic

Ethnic formats are targeted toward ethnic groups or people united by a language other than English. African Americans constitute a major ethnic group in many large markets and in towns of various sizes in the South. Stations targeting this group often combine disco and hip-hop music with information of interest to the African-American community.

Spanish-language stations program music and information for Cuban Americans, Mexican Americans, Puerto Ricans, and others whose primary language is Spanish. In addition, many stations broadcast a variety of content in one or more foreign languages, including French, Polish, Japanese, and Greek.

Religion

This format is characterized by hymns and other religious music, sermons, religious services, talks, interviews, and discussions. The particular program makeup is influenced heavily by the type of licensee. Some stations are licensed to churches and religious organizations that are more interested in spreading their message than in the size or composition of the audience. However, ratings and demographics are of major concern to a second type of licensee, the conventional entrepreneur, who sells blocks of time to churches and religious organizations and spots to advertisers.

Variety

The variety format exists chiefly in one-station markets or where other formats do not meet the music or information needs of several desirable demographics. In a one-station market, for example, the format may include music for all age groups, news, weather, sports, and public affairs. Features would be selected for their appeal to the makeup of the community.

The format is programmed to satisfy the available audience. During the morning hours, music may be suited to adults at home. In the afternoon and evening, the sound may become more contemporary for teenagers and young adults.

Program Sources

Radio stations use three major sources of programs: local, syndicated, and network.

Local

Local programming is the principal source for most stations. For stations with a music format, it includes both music and information content.

Recording companies are anxious to have their product played on radio stations, since air play is an important determinant of sales. Accordingly, they provide most stations with free, promotional copies. To ensure good service, the station must nurture close relationships with the companies. That can be done by maintaining regular contact, sending them copies of the playlist, and keeping them informed of success in reaching those demographics to which the recordings appeal.

Some stations obtain recordings from local stores under a trade-out arrangement. Stations in many small markets do not receive promotional copies and subscribe to a recording service for current releases.

Examples of locally produced information content on a music-format station include news, sports, and public affairs. Stations with an information format rely heavily on local production for news, talk, features, sports, and public affairs.

Radio stations also engage in remotes from retail stores, malls, and other business locations. Such broadcasts can be a useful promotional tool. Indeed, some stations have bought fiberglass or inflatable studios in the shape of giant radio receivers to increase their visibility on such occasions. However, remotes must be selected with care, since they may interrupt the regular flow of programming. They must also be planned in close cooperation with the sales department.

Syndicated

Syndicators provide stations with programs and with complete music formats.

Programs

Syndicated offerings range from 60- or 90-second features on health, finance, politics, and assorted other subjects, to programs of several hours’ duration.

Long-form programming featuring nationally known talk personalities like Rush Limbaugh and Sean Hannity offers stations quality and cost-efficient content. Such is the appeal of syndicated product that it has even taken over the traditionally locally produced morning drive period on many stations and replaced station hosts with the likes of Don Imus and Howard Stern. Regional morning team programs are also available, especially in the South.

Barter is the primary method of syndicated program acquisition. Other programs are offered on a cash basis, the price determined by factors such as market size, the appeal of the program, and competition for it. Still other programs are available to the station without charge.

Formats

The entire music programming of some stations is provided by format syndicators.

Stations receive from the syndicator, typically via satellite, music in the desired format and then insert commercials, promotional, public service, and ID announcements, and other nonmusic content.

Syndicated formats are found mostly in fully automated stations. However, many formats may be used in semi-automated and live-operated stations.

Some formats are sold to stations and others are leased. Cost is determined mostly by the type of format and size of the market.

In addition to providing music, many format syndicators offer their services to stations as consultants on programming, promotion, and research.

Network

The programming of most national networks is designed for specific demographics or formats. The staples are music, news, and talk. Other programs vary according to the interests of the targeted audiences.

Many stations also receive news and other informational programming from regional or state networks. Ad-hoc networks are organized in many parts of the country for the coverage of special events and sports.

Strategies

Selection of a format is the first and most important step in the development of a station’s programming strategy. It is also the most difficult. In most markets, music formats with the greatest appeal to the most-sought demographics (persons aged 25 to 54) already have been taken. AM stations experience particular problems, as evidenced by their movement away from music formats and toward news, talk, or a combination. With the increasing fragmentation of formats, FM stations also face difficulties in trying to position themselves in a way that sets them apart from stations with similar formats. “Niche programming” has become the key.

Among the factors that influence the format selection are

Generally, the larger the market, the more specialized the format must be to attract an audience.

Demographic characteristics and trends are important in predicting the appeal of particular formats since, as we have seen, music and other program preferences are linked closely to age, gender, income level, and ethnicity. The makeup of the workforce and the proportion of professional, industrial, and agricultural employees also provide useful pointers. The region of the country in which the station is located and the extent to which it serves chiefly urban, suburban, or rural residents, or some combination, give additional clues to content appeal.

Consideration of the degree to which competing stations have targeted all desirable demographics will indicate if there is a void in the marketplace. Persons deemed most desirable by advertisers are, in order, adults aged 25 to 54, 18 to 49, and 18 to 34. If there is a void, the station may select a format that meets the needs of the unserved or underserved audience. On the other hand, it may be determined that one or more stations are vulnerable to direct format competition, and that audience may be taken from them by better format execution and promotion.

The size and demographic composition of the audience are key factors in generating advertising dollars. For that reason, projections of the potential audience and of advertising revenues are major criteria in the formatdecision process.

The size of the potential audience is determined by the number of people who can receive the station’s programs. Accordingly, the power at which a station is authorized to broadcast is important. The greater the power, the greater the coverage. Coverage also is influenced by the frequency of an AM station and the antenna height of an FM station. The lower the frequency and the higher the antenna, the greater the range of the station’s signal.

Format selection may take into account another technical consideration. The superiority of FM over AM sound fidelity has attracted a majority of music listeners to FM stations and posed programming dilemmas for AM stations in many markets.

The financial cost of the format and of promoting the station to capture enough listeners to appeal to advertisers must be considered.

Stations that opt for a music format also must decide on other content elements to include in their programming.

Next, the station decides how to execute the programming to attract and retain the target audience. The decision must take into account the needs and expectations of the listeners.

People turn to a music-format station chiefly for entertainment or relaxation, to an all-news station for information, and to an all-talk station for a variety of reasons, including information, opinion, and companionship. They expect to hear a familiar sound, one with which they feel comfortable. The format, therefore, must be executed with consistency.

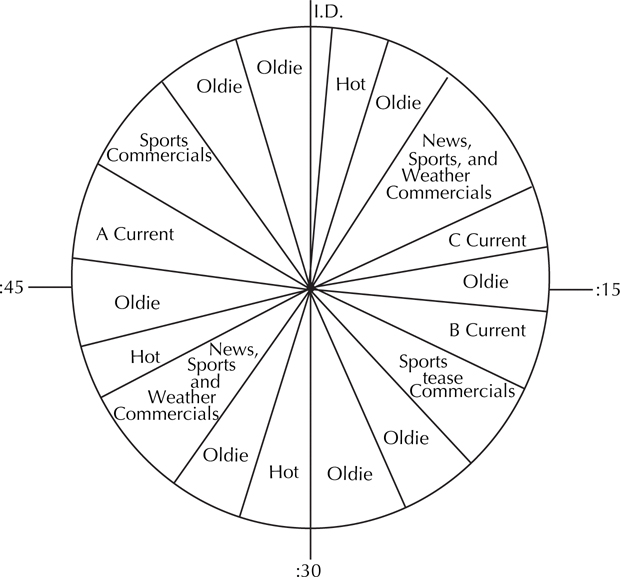

The most common tool to obtain consistency is the format wheel or format clock, which identifies the mix and sequence of program elements in a onehour period. Figure 4.2 shows a format wheel for a contemporary hit station in morning drive time.

Figure 4.2 Morning drive format wheel: contemporary hit radio station. Hot: chart position 1–10; A Current: 11–20; B Current: 21–30; C Current: 31–40.

The particular composition of an audience, its needs, moods, and the activities in which it engages change during the day. Stations attempt to respond to those changes through dayparting. On weekdays, the dayparts are

• Morning drive time (6:00 A.M. to 10:00 A.M.): Most listeners want to be brought up-to-date with news and with weather and traffic conditions.

• Midday (10:00 A.M. to 3:00 P.M.): The majority of listeners are homemakers and office workers, and both music and information programming are tailored to their needs.

• Afternoon drive time (3:00 P.M. to 7:00 P.M.): Teenagers return from school and adults drive home from work. For the most part, the former seek entertainment and the latter a mix of entertainment and information.

• Evening (7:00 P.M. to midnight): The audience of most stations is composed chiefly of people desiring entertainment or relaxation.

• Overnight (midnight to 6:00 A.M.): Shift workers, college students seeking entertainment, and persons seeking companionship constitute the bulk of the audience.

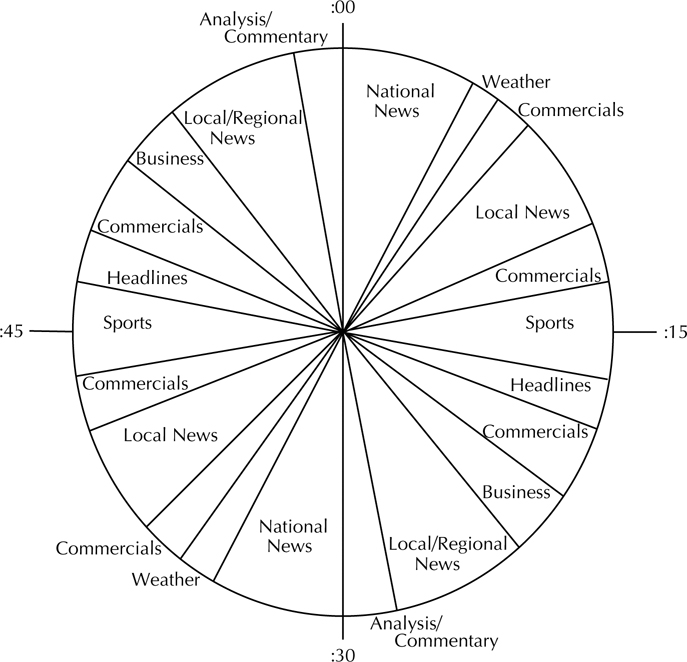

All-news stations broadcast their content in cycles, with a certain time elapsing before each element is repeated. Figure 4.3 shows a format wheel for such a station.

Figure 4.3 Format wheel: all-news station.

Audience size is computed by quarter hour, and so stations strive to attract the maximum possible audience in each quarter-hour period. However, audience members do not have to listen continuously for 15 minutes to be counted. Audience measurement companies credit a station with a listener if a person is tuned in for five or more minutes in any quarter hour. One technique to retain listeners from one quarter hour to the next is to schedule a music sweep (i.e., uninterrupted music) over each quarter-hour mark. Nonmusic content, which often prompts dial-switching, is placed within the quarter hour. Another is a tease or bumper. Here, the disc jockey or talk host previews what is coming up in the next segment.

A station’s success in maintaining audience may be judged by the amount of time a person listens during a specific daypart. This is known as time spent listening, or TSL. It is calculated by multiplying the number of quarter hours in a daypart by the average quarter-hour audience and dividing the result by the cumulative audience. For example, a station has an average audience of 5,700 and a cumulative audience of 25,500 among persons aged 25 to 49 during morning drive Monday through Friday. The TSL is 80 (number of quarter hours) times 5,700 (average audience) divided by 25,500 (cumulative audience), or 17.9 quarter hours. To determine audience turnover, or the number of times an audience changes during a time period, the cumulative audience is divided by the average audience. In this example, it is 4.5.

Essentially the same music is available to all stations in a market with a particular format. An important strategic consideration, therefore, is the selection of recordings for the playlist and their rotation. The playlist is the listing of recordings played over the course of a period of time, usually a week. Rotation refers to the frequency with which each is played.

Stations rely on several sources in deciding what to keep on the playlist and what to add and delete. Among those used most often are trade magazines, such as Billboard and R&R (Radio & Records), tip sheets, and newsletters. They reflect the popularity of recordings in different formats across the nation. To determine local appeal, stations check on sales with area music stores.

To increase their information base, many stations engage in continuing efforts to obtain listener feedback to the music being played or contemplated for addition to the playlist. The most common method is call-out research. The station plays over the telephone short excerpts (called “hooks”) of music selections and asks respondents for their reactions. The results are tabulated and assist in tracking the popularity of recordings and making decisions on playlist content. Such research is relatively inexpensive, but only a limited number of hooks can be played before participants grow tired.

Another method is auditorium testing. Several dozen people are invited to a large room or auditorium and asked to rate as many as 400 hooks. They are paid and, generally, are chosen from the age group targeted by the station. They may be regular listeners, those who favor a competing station, or a combination. Auditorium testing is more expensive than call-out research and usually is attempted only periodically. That prevents close monitoring of changing music preferences and regular refinement of the playlist.

In an attempt to ensure that programming is tuned to the needs of the target audience, stations are paying increased attention to nonmusic research. Many are building databases to develop listener profiles. Income, lifestyle, product usage, and leisure activity are examples of information that is collected and stored. Images of the station, its programming, personalities, and other elements are obtained through focus groups, which bring together 10 to 12 people for a controlled discussion led by a moderator. Often, the results provide ideas for more extensive research. Market perceptual studies are conducted by telephone interview or mail survey among targeted listeners to identify perceptions of a station’s position in the market and its various characteristics. Telephone interviews also are used in format searches, attempts to ascertain if there is a need or place for various formats or elements within a format.

In some formats and on some stations, primary emphasis is given to the music or information content. The personality of the announcer is secondary. However, since the announcer is the link between the station and the audience, many stations encourage announcers to project their personality with the expectation that it will provide another competitive weapon. In either situation, announcers are important in the creation of a station’s image and are chosen to reflect that image. If personality is emphasized, announcers are scheduled during those dayparts when their personality suits the mood of the audience.

Strategy considerations also may involve the possible use of automation. The station must decide whether its benefits outweigh its shortcomings and whether it may be used advantageously over the entire broadcast day or in certain dayparts. Automation offers the advantages of a consistent, professional sound, eliminates personnel problems, and may result in cost savings. However, it removes the element of personality and deprives the station of spontaneity and flexibility.

Programming must be promoted constantly to retain the existing audience and to attract new listeners. The role of promotion is discussed in Chapter 6, “Broadcast Promotion and Marketing.” It should be noted here that stations seek to gain competitive advantage through on-air and off-air promotion of image, programming, and personalities. They hope that the result will be a clear public perception of what the station does and how it can satisfy audience needs.

A final and most important strategic consideration is the station’s commercial policy. Most listeners to music-format stations have little tolerance for interruptions in music and may seek out another station when commercials air. Commercial policy usually sets forth the commercial load (i.e., the number of commercials allowed per hour) and the frequency of breaks for com-mercials and other nonmusic content. Commercial policy is discussed further in Chapter 5, “Broadcast Sales.”

TELEVISION STATION PROGRAMMING

Programming a commercial television station differs markedly from programming a radio station. While the radio programmer identifies a specific audience and broadcasts to it throughout the day, the television programmer targets a general audience and attempts to respond to the preferences of those persons who are available to view.

A radio station competes for audience primarily against the other radio stations in the market that seek to attract similar demographics. A television station is in competition against all other television stations in the market and against cable and direct broadcast satellite. Additional competition for the viewers’ time comes from videocassette recorders, DVD players, and the Internet.

Network programming occupies only a minor place in the schedule of most radio stations. It is a dominant force in television, providing a major part of the schedule for stations affiliated with the three original networks—ABC, CBS, and NBC. It plays a lesser, though still very important, role in the offerings of affiliates of Fox, The WB, and UPN. (At the time of writing, the future of PAX TV was uncertain. Accordingly, it will not be considered here.)

Programming success in television rests heavily on the ability to produce or buy programs with audience appeal, air them at times when they can be seen by the audience to which they appeal, and build individual programs into a schedule that encourages viewers to tune to the station and remain with it from one program to another.

Program Sources

Television stations affiliated with a network rely on three principal sources of programs: the network, program syndicators, and local production. Independent stations (i.e., those not affiliated with a permanent network) use syndicated and local production and receive sports and specials from ad-hoc networks.

Network

ABC, CBS, and NBC provide affiliates with the bulk of their programming. Weekday daytime hours consist of news magazines, soap operas, a game show, and network news. In prime time, entertainment, news magazines, and some sports are broadcast. Talk-variety, news interviews, and news characterize the late night and overnight periods.

On weekends, they schedule news magazines and programs for children and teenagers on Saturday mornings, sports in the afternoon, and entertainment in prime time. Daytime on Sundays includes news-magazine and newsinterview programs and sports, followed by prime-time entertainment.

The networks produce their news and sports broadcasts and a growing number of their prime-time entertainment programs. However, they continue to purchase a significant amount of entertainment from independent production companies.

Fox, The WB, and UPN supply fewer hours for their affiliates than the original networks. Weekdays, Fox programs two hours of entertainment in prime time. On Saturday, children’s programs are aired in the morning, sports in the afternoon, and entertainment in prime time, followed by more entertainment. A morning news-interview program, afternoon sports, and three hours of prime-time entertainment make up the Sunday schedule.

The WB airs a two-hour, young-adult entertainment block weekday afternoons and two hours of entertainment in prime time. Five hours of morning children’s programming are the network’s only offerings on Saturday. The network’s Sunday schedule consists of two hours of primetime entertainment.

UPN programs two hours of entertainment in prime time Monday through Friday and a movie on Saturday afternoons.

Program Syndicators

Syndicated programs are used by networkaffiliated stations to fill many of the periods during which the network does not provide programming. Independent stations rely heavily on such programs during all dayparts.

There are two major categories of syndicated programs:13

• Off-network, which denotes that the programs have been broadcast on a network and now are available for purchase by stations and other outlets. They include a large number of situation comedy and dramatic programs that attracted large and loyal audiences during their network runs.

• First-run, which describes programs produced for sale directly to stations. The kind of content available varies from year to year. In the early years of the twenty-first century, among the most plentiful and popular offerings, were talk, game, and court shows.

Feature films and cartoons also are distributed by syndicators. Decisions on syndicated program acquisitions are based on program availability, cost, and audience appeal.

As noted later in the chapter, the station rep company is an important source of information on available programs. Many stations use additional sources, such as the annual Television Programming Source Books, published by BiB Channels. This three-volume series contains information on films and film packages, and lists short-and long-form TV film and tape series, with details of program length, number of episodes, story line, distributor, and distribution terms. Product is available to a station only if it has not already been obtained by another station in the market.

Even though stations often announce that they have bought a syndicated program, what they have bought, in fact, are the exclusive rights to broadcast a program over a specific period of time. The rights are contained in a license agreement between the syndicator and the station. It details, among other items, the series title, license term, number of programs, license fee, method of delivery, and payment terms. The fee is based on a number of factors, including the size of the market, competition for the program from stations in the market, the age of the program, and the time period during which it will be broadcast. The negotiating skills of the person representing the station also may be influential. In the case of feature films, market size, competition, and the age of the films are taken into account, as well as the success they achieved during their showing in movie theaters or on a network.

The dramatic increase in the cost of syndicated product, combined with the emergence and growth of barter programming (discussed below), have led to an important change in the program manager’s traditional role in syndicated program purchasing. Today, because of the increased emphasis on the bottom line, the programmer is likely to be only one of several key station personnel involved in purchasing decisions. Others include the general manager, sales manager, and business manager. In many stations, the general manager has primary responsibility, while the program manager merely administers decisions.

In determining what to buy and how much to pay, the station should give particular attention to the ratings potential and projected revenues of syndicated programs. Their appeal may be ascertained by studying their performance in other markets, particularly those with a similar population makeup. Nielsen’s Report on Syndicated Programs provides detailed information on the size and demographic composition of the audiences for syndicated programs in all markets, in different dayparts, and against different program competition. Clues to the appeal of off-network programs may be gleaned from their performance in the market when they aired on a network.

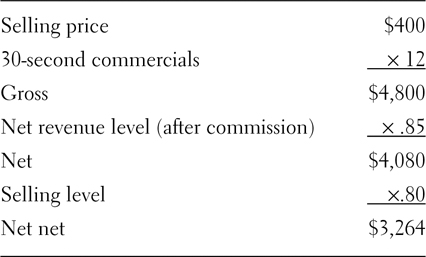

Calculating revenue potential requires consideration of (1) spot inventory, or the number of 30-second spots available in each program; (2) the average selling price in the daypart in which the program will be broadcast; and (3) the selling level, that is, the percentage of spots likely to be sold. Multiplying the selling price by the number of spots available produces the gross revenue. The gross is reduced by 15 percent to allow for commissions paid by the station to account executives, reps, and advertising agencies, producing the net. That figure is reduced further by the projected selling level (most stations use 80 percent) to give what is known as the net net.

Assume that a network-affiliated station is contemplating the purchase of a half-hour, off-network series. Six commercial minutes are available and the average selling price in the daypart for a 30-second spot is $400. The calculation would be as follows:

The projected revenue of $3,264 for each episode applies only to the first year. Projections for subsequent years will take into account possible changes in the spot rate. For example, rates in the daypart may increase to keep pace with inflation. A decrease might result if the program were moved to a less costly daypart.

Having calculated the net net revenue potential of each episode over the life of the contract, the station must then consider how much it can afford to pay per episode. The actual price will be determined through negotiations between the syndicator and the station.14

When the contract is signed, the station usually makes a down payment and pays the balance in installments. As noted in Chapter 2, “Financial Management,” costs are assigned according to an amortization schedule for accounting purposes. The station may select the straight line method, which means that an equal value is placed on each broadcast of each episode. Alternatively, it may opt for accelerated amortization or the declining value method, which assumes that the value of each episode decreases with each broadcast. Accordingly, the station assigns to each broadcast a declining percentage of total cost. A program with six runs may be expensed as follows: run 1—40 percent; 2—30 percent; 3—15 percent; 4—10 percent; 5—5 percent; 6—0 percent.

It is becoming increasingly difficult for stations to buy attractive syndicated programs for cash. Some are available only through barter.

In a barter transaction, the syndicator provides the program at no cost but, in return, retains for sale some of the commercial inventory. In a 30-minute program, for example, two minutes may be retained, leaving four minutes for sale by the station. More common is the cash + barter arrangement, whereby the station pays a fee for the program and also surrenders time to the syndicator.

At its inception, barter was viewed as a means whereby stations could control soaring program costs. Syndicators emphasized that the value of the commercial time surrendered would represent a much lower cost to the station than if the program were bought on a straight cash basis. Furthermore, the small amount of inventory retained by the syndicator probably would not hurt profits, since 10 to 15 percent of commercial time generally remains unsold.

Barter does permit stations to obtain competitive product without putting out large amounts of cash, and to exchange time that might not be used for lower overall program costs. However, it has become such a dominant force that stations that would be willing to pay cash do not have that option. In addition, program costs have continued to escalate and stations have been left with less inventory to recoup their programming investment. Furthermore, barter now places stations in direct competition with syndicators for the sale of time to national advertisers in the same program.

Local Production

The focus of local production is on local newscasts and public affairs programs, chiefly face-to-face interviews. Other local productions may include magazine, music video, exercise, sports, and children’s programs, and occasional documentaries.

Programming Factors

The TV program manager weighs many factors in making program acquisition and scheduling decisions. Among the more important are these:

Since the size of the television audience is predictable in each daypart, a station attracts viewers at the expense of its competitors. Noting the strength or weakness of the competition, both among total viewers and particular demographics, the station can schedule appropriate programs. In a single time period, there are two basic options. One is to try to draw viewers from competing stations with a program of similar audience appeal. The second is to schedule a program with a different appeal to attract those whose interests are not being addressed.

It is advantageous to a station to air programs that attract large audiences. It is much more advantageous if audiences can be inherited from preceding programs and retained for those that follow. In scheduling, consideration is given to both possibilities.

A challenge in scheduling programs to capitalize on this so-called audience flow has grown out of the spread in ownership of remote-control pads. Viewers use them to switch from channel to channel within and between programs to explore their options. This practice is known as flipping.15

Series programs scheduled in the same time period each weekday can become part of the audience’s daily television viewing routine. Encouraging such habit formation usually is an important goal.

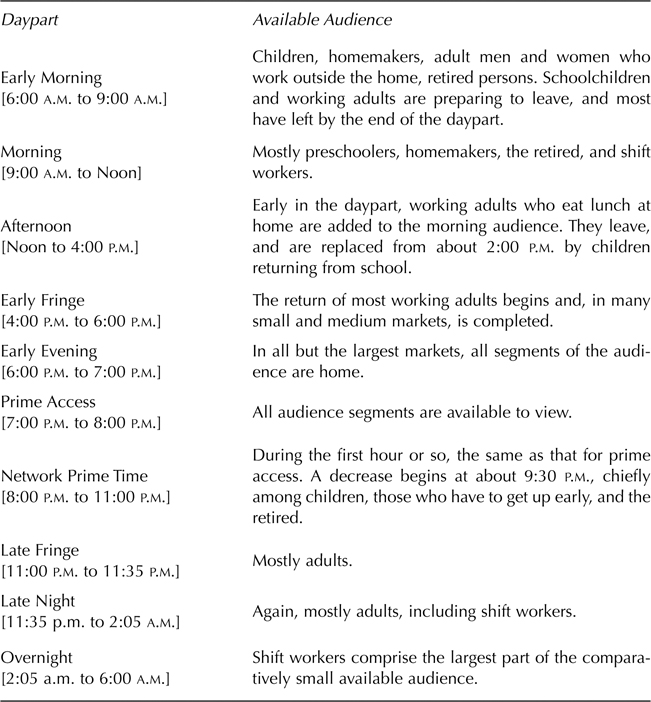

The audience of a market, and the availability of different parts of the audience in various dayparts, are major determinants of program selection and scheduling. Figure 4.4 shows the dayparts on weekdays and the audience available in each.

Figure 4.4 Television dayparts and available audience (all times are ET).

Weekends present a different picture. In theory, all children and many adults are potential viewers. However, shopping, social, and sporting activities influence the number and kind of people who are free to watch television on Saturdays. The nature of the local economy is important, too. More adults usually are available in white-collar than in blue-collar communities, where Saturday work is not uncommon. On Sundays, religious pursuits may be added to shopping, social, and sporting activities as alternatives to television viewing.

Audiences are attracted in large numbers to many entertainment programs. If audience interest in other kinds of content is high in a particular market, or if the station believes that interest can be stimulated, it may wish to produce or buy programs that respond to such interest.

To be successful, programs must attract advertisers as well as audiences. The principal target of most local TV advertisers is adults aged 25 to 54. Selecting programs with low audience appeal, or with appeal chiefly to demographics in which advertisers are not interested, leads to financial problems.

The amount of money available for program production and purchases is an important determinant of what can be programmed. Costs of many popular off-network programs have been driven up significantly in recent years, making it difficult for a station to use large numbers of such programs as a stepping-stone to success.

Many syndicated program and feature film contracts permit multiple broadcasts over a period of years. In addition to recently purchased product, such content still may be available for airing.

It has been noted that most stations produce few programs, except news and public affairs. However, a station with an adequate budget, equipment, and technical facilities, competent production personnel, and sources of appropriate talent may contemplate producing other kinds of programs, especially if audience and advertiser interest are strong.

Scheduling Strategies

Consideration of the above factors will suggest program scheduling strategies suited to the competitive situation in which the station finds itself. The following strategies are among those used most commonly:

• Head-to-head: A program that appeals to an audience similar to that being sought by a competing station or stations. Early- and late-night newscasts usually are scheduled against each other on stations affiliated with the original networks and provide an example of this strategy.

• Counter: A program that appeals to a different audience from that targeted by the competition. A program with principal appeal to adults at the same time as a children’s program on another station is an example of counterprogramming.

• Strip: Scheduling a program series at the same time each day, usually Monday through Friday. This practice, also known as horizontal programming, encourages habit formation by the audience. However, if the program does not attract a sizable audience, the strategy may backfire, since failure will be experienced every day. With syndicated series, the strategy is desirable only if there are enough episodes to schedule over several months, at least.

• Checkerboard: Airing a different program series in the same time period daily. This strategy has several drawbacks. It is expensive, since the station may have to buy as many as five different series. It is difficult to promote. Finally, it does not permit the station to capitalize on the element of audience habit.

• Block: Scheduling several programs with similar audience appeal back-toback, usually for two hours or more. This strategy also is called vertical programming and seeks to encourage audience flow.

Feature films pose a special scheduling challenge. Film packages contain both good and not-so-good movies, and not all have similar audience appeal. Many stations try to surmount the problem by airing films under an umbrella series title and identifying an element for promotional emphasis. If the movie has won awards, for example, the award-winning elements lend themselves to such an approach.

Three decades ago, Philip F. von Ladau, vice president and general manager of Marketron, Inc., set forth ten basic programming principles. Despite changes in audience habits resulting from the massive growth in the number of viewing options and the impact of the remote-control pad, judicious application of the principles can still lead to successful scheduling. They are

1. Attack where shares of audience are equally divided. It’s a lot easier to take a little audience from each of several stations than a lot of audience from a dominant program.

2. Build both ways from a strong program. Take advantage of early tune-in to a strong program creating “free” sampling of a good preceding show; late tune-outs to accomplish the same for the following. This falls under the principle that it’s easier to sustain an audience than to build one.

3. Sequence programs demographically. Don’t force unnecessary audience turnover.

4. When a change in appeal is called for, accomplish it in easy stages. When the available audience dictates a change, do so with a program type that will hold as large a share of the preceding audience as possible, rather than attempting to completely change the demographic appeal.

5. Place “new” programs at time periods of greatest tune-in. This amounts to free advertising through happenstance sampling. People turning on their sets generally leave them at the station last used; thus, at times of building (increasing) set usage, a significant number of people may inadvertently be exposed to your new show.

6. Keep a “winning” program in its current position. Changing competition must, of course, be taken into consideration. But when people are in the habit of finding a popular program in a particular time period, moving it risks an audience loss.

7. Counter-program to present viewers with a reasonable alternative to the other fare. It’s generally better to offer something different than just another version of the types of programs already being aired by the competition.

8. Program to those people who are available. A lot of errors are made here by considering the age/sex makeup of all the audiences using TV. What is really available to most programs, particularly independent and/or individual-station-placed programs, is just the audience that remains after the dominant show has commanded its share.

9. In buying, always consider how it would be to have the offered program opposite you. It may be worth a small going-in monetary loss as opposed to the big one that might be created with the subject program opposite your existing properties.

10. Don’t place an expensive program in a time period where there is insufficient audience or revenue potential, enough at least to break even in combination with its preceding and following properties.16

PROGRAMMING THE NETWORK AFFILIATE

Even though stations affiliated with the Fox, The WB, and UPN networks are “network affiliates,” their networks’ schedules are much more limited than those of ABC, CBS, and NBC. As a result, they operate like independent stations much of the time. For that reason, they will be considered with the independents later in the chapter.

Affiliation with one of the three original networks offers many advantages. It has been noted that the network fills a significant part of an affiliate’s program schedule, mostly at no direct cost.

Many network programs attract large audiences, thus increasing the value of the time the station sells in and around them. Skillful scheduling and promotion also permit the station to attract audiences to locally scheduled programs before, between, and after network offerings. Similar assistance in boosting audiences is afforded through the network’s publicity and promotion.

However, the affiliate programmer’s job is not without challenge. Cable and DBS allow viewers to select from dozens of channels, which offer stiff competition and which have cut deeply into the affiliates’ audiences.

Network-Affiliate Relations

The relationship between a network and an affiliated station is governed by an affiliation contract. Specific contracts differ from network to network and are undergoing some changes, particularly on the terms of compensation that networks traditionally have paid to their affiliates. Generally, however, they contain the following clauses:

1. The network agrees to provide, and deliver to the station, a variety of programs.

2. The station has the right of first refusal. In other words, the network must offer programs first to its affiliated station in the market.

3. The station may reject any network program it believes to be unsatisfactory, unsuitable, or contrary to the public interest. In such cases, the network may offer the program to another station or program transmission service in the market. In practice, affiliated stations clear (i.e., carry) most of their network’s programs. When they refuse, it is generally because they consider the program too controversial or because they wish to broadcast a program of special local interest.

4. The station may broadcast a network program on a delayed basis, but only with network approval. When the delayed broadcast occurs, the station must announce that the program was presented earlier on the network.

5. The station may not add or delete material from a network program without prior written authorization from the network.

6. Within a network program period, the station may not delete any network identification, program promotion, or production credit announcement, except promotional announcements for a program the station will not carry. In such cases, only a network or station promotional announcement or public service announcement may be substituted.

7. The network may cancel a previously announced program and substitute another program.

8. The station may broadcast locally originated announcements in station break periods between and during network programs. However, the placement and duration of such periods are determined by the network.

9. When an affiliated station is sold, the network has the right to determine whether to accept the change.

Network Programming

The original networks provide their affiliates with programs in most dayparts.

Weekday early-morning network programming consists of news magazines. A woman’s magazine program (ABC) and game show (CBS) fill part of the morning, followed by an afternoon block of soap operas and news in early evening on all three networks. Network prime time comprises a variety of programs: reality, situation comedies, dramas, feature films and made-for-TV movies, news magazines, specials, and sports. Late night is made up of newsinterview and talk-variety programs. ABC and CBS air news during all or part of the overnight daypart.

The networks’ weekend lineup varies, chiefly as a result of sports coverage on Saturday and Sunday afternoons. News magazines, cartoons, and other child- and teen-appeal programs are aired on Saturday mornings. Sports characterize Saturday afternoons, usually followed by the network news. Network prime time consists of entertainment. NBC is the only network that programs the late-night slot, with “Saturday Night Live.”

News magazines and news interviews are aired on Sunday mornings, and sports during the afternoons. Network news precedes prime-time programming, which starts at 7:00 P.M.

Scheduling

Since a network fills the major part of an affiliated station’s broadcast day, the program manager’s chief scheduling responsibility is for those periods during which the network is not feeding programs. Of course, if the station determines that it will not clear or will delay broadcast of a network program, additional scheduling decisions must be made. Programming possibilities on weekdays include the following:

Early Morning (6:00 A.M. to 9:00 A.M.)

Many affiliates start the daypart with local news and/or news-magazine programs, and most join the networks at 7:00 A.M. for their respective news magazines. Children and teenagers are not being served. Locally produced children’s programs, syndicated cartoons, and off-network sitcoms or drama-adventure series offer alternatives for part or all of the period.

Morning (9:00 A.M. to Noon)

Homemakers are a principal target in this daypart. During the first two hours, the networks are not providing programs. Options include local or syndicated talk, discussion, or magazine programs oriented toward women, and game shows. Off-network situation comedies starring children or with slapstick elements may bring children as well as adults to the set. ABC and CBS return at 11:00 A.M. and most affiliates clear network programming through the end of the period. Syndicated talk is the choice of many NBC affiliates.

Afternoon (Noon to 4:00 P.M.)

Between noon and 12:30, many affiliates opt for local news or a news magazine, both of which provide an opportunity to promote later newscasts. Syndicated entertainment, such as quiz or game shows and situation comedies, is an alternative. From 12:30 P.M. (CBS) or 1:00 P.M. (ABC and NBC), affiliates generally carry the network soap opera block. It runs until 4:00 P.M. on ABC and CBS. NBC affiliates have an opportunity to counter-program starting at 3:00 P.M. The alternatives include syndicated talk with strong appeal to women, or cartoons and situation comedies with teenage and child appeal to target returning schoolchildren and teenagers.

Early Fringe (4:00 P.M. to 6:00 P.M.)

This is the start of the longest period for which an affiliate has programming responsibility. At the same time, it offers a station the opportunity to generate significant advertising revenues and build the adult audience for its local news.

The growth in audience size and diversity allows stations to engage successfully in counter-programming. Thirty-minute and one-hour off-network and first-run syndicated content fit easily into the period, and many stations have discovered that audiences respond well to blocks of programs of the same genre.

Placement of local news is a major strategic factor. Airing it at 5:00 P.M. or 5:30 P.M. rules out the possibility of back-to-back hour-long programs. However, a succession of two or three off-network situation comedies with increasingly older appeal can bring youngsters to the set first, followed by teenagers and adults. An hour-long syndicated talk program attracts the adult demographics desired for news at 5:00 P.M. Movies may be considered by stations that do not air local news until 6:00 P.M., but their appeal varies. They also pose some scheduling problems because of their varying lengths. Made-for-television movies are consistent in length, but have proven less appealing than feature films.

Early Evening (6:00 P.M. to 7:00 P.M.)

The length of the local newscast and the periods selected both for local and network news influence the schedule in this daypart. The 30-minute network newscast may be preceded or followed by a 30-minute local newscast. An hour-long local news program may be followed by network news in the first half hour of prime access, or a 90-minute news block may start with 30 minutes of local news, followed by network news, and a final 30 minutes of local news. In most major markets, longer news blocks are common.

Prime Access (7:00 P.M. to 8:00 P.M.)

The Prime-Time Access Rule restricting what could be shown by some network affiliates formerly influenced program choices in this daypart. With the rule’s termination in 1996, stations in all markets are free to air whatever they please. Most stations have filled the time slot with syndicated programs. Quiz and game shows, as well as offnetwork situation comedies, have proved very strong in this period. News magazine programs enable stations to inherit adults from the preceding newscasts.

Network Prime Time (8:00 P.M. to 11:00 P.M.)

Most affiliates carry network programming during this entire daypart. If a network program is not competitive, or if most of the network’s schedule on a given night is faring poorly, the station may consider preempting and substituting its own programming. Syndicated entertainment programs can fill a 30- or 60-minute period, while movies may produce the desired audience for periods of 90 minutes or two hours.

Late Fringe (11:00 P.M. to 11:35 P.M.)

Affiliated stations usually air their late local news in this time slot.

Late Night (11:35 P.M. to 2:05 A.M.)

NBC provides affiliates with programming for the entire period, and CBS programs all but 30 minutes. ABC fills only the 11:35 P.M. to 1:05 A.M. slot. Options for CBS and ABC affiliates include off-network situation comedies and, for ABC affiliates, syndicated talk or entertainment-based programs and off-network dramatic series.

Overnight (2:05 A.M. to 6:00 A.M.)

Affiliates that remain on the air usually carry news fed by the network during part or all of the period.

Weekend scheduling is influenced by network sports programming, which varies from season to season. On Saturday afternoons, the station may have to program a period of two or more hours. Syndicated entertainment and feature films are among the most popular options. Many stations air a 30-minute local newscast at 6:00 P.M. and follow network news with a one-hour or two 30-minute syndicated entertainment programs from 7:00 to 8:00 P.M. Local late news follows network prime time on many affiliated stations. ABC and CBS affiliates do not receive network programming during late night and often run movies, syndicated talk, off-network drama series, or situation comedies in the time periods.

Many affiliates carry religion, public affairs, or children’s programs on Sunday mornings before joining the network for news-magazine and newsinterview broadcasts. Depending on the season, the station may have to schedule afternoon programs before or after network sports. Again, syndicated entertainment and feature films are common choices, with local and network news between 6:00 and 7:00 P.M. After network prime time, most affiliates air a 30-minute local newscast. Movies, syndicated entertainment, and religion are among the alternatives for the late-night period.

PROGRAMMING THE INDEPENDENT STATION

Programming an independent television station is a most challenging job. The challenge is less difficult for stations affiliated with Fox, The WB, and UPN, which receive varying amounts of programming from their networks. However, programmers still are left with many hours to fill each day, and independents cannot rely to the same degree as competing affiliates on network programs to encourage the flow of viewers into locally scheduled time periods, thus enhancing not only audience size but also the value of time the station sells to advertisers.

By definition, the true independent does not have access to programs on any permanent network, many of which attract large audiences to the affiliates with which it competes. It does not benefit from network promotion and publicity, which draw viewers to the affiliates. Unlike the affiliate, the true independent must provide all the programs it airs, a task that has been aggravated by the increased competition for attractive off-network syndicated programs and by their growing cost.

The independent does not enjoy the comparatively high rates that affiliates can charge advertisers for time in and around network programs. Further, the independent often has to contend with a negative attitude on the part of time buyers.

The challenge is difficult but not impossible. In large measure, independents’ achievements have been based on the wisdom of their program selection, the imagination of their promotion efforts and, above all, on the effectiveness of their program scheduling.

For the most part, the programming weapons of independents have been movies, syndicated talk, off-network entertainment programs—especially situation comedies and action-drama series—syndicated or local children’s programs, and live sports. Many independents also carry specials and, occasionally, programs rejected by affiliates.

Network promotion has aided Fox affiliates in positioning themselves, while station promotion has enabled true independents to benefit from their image as a source of alternative programming or as the station to watch for movies or sports. However, positioning the independent is becoming more difficult with the increase in both alternative and specialized program offerings on cable and DBS.

At the heart of the strategy of many independents is the realization that it is unrealistic to try to beat affiliates in all time periods. Rather, they have identified dayparts in which they can compete and have programmed accordingly. Generally, the dayparts have been those in which all affiliates seek similar audiences or in which parts of the available audience have been unserved or underserved. Their strategy has been based chiefly on counter-programming.

The success of their counter-programming points to one of the few programming advantages enjoyed by true independent stations: flexibility in scheduling. Affiliates are expected to carry most of the programming of their networks. The network schedule also determines the amount and times of locally programmed periods. The independent, on the other hand, is free to develop its own schedule and to take advantage of the opportunities to attract audiences whose interests are not being satisfied. Among the best opportunities for counter-programming on weekdays are the following:

Early Morning

While most affiliates are carrying adult-appeal network or local news-magazine shows or local news programs, the independent can capture children with syndicated cartoons or locally produced children’s programs.

Afternoon

With affiliates of ABC, CBS, and NBC airing network soap operas, the independent has taken advantage of the abundance of syndicated talk programs to offer an alternative. Off-network situation comedies and male-oriented action dramas also have proved effective options. As the daypart progresses, cartoons and other child- and teenage-appeal content is favored by many stations. WB affiliates receive young-adult programming from the network during the last hour of the period.

Early Fringe

The WB fills the first hour of the daypart for their affiliates with more young-adult programs. Many stations move to a block of off-network situation comedies with appeal to both adults and children. The strategy also serves as a counter to local news, which usually starts before the end of the period, and as a bridge to the adult-appeal programming that follows. True independents also look to situation comedies or counter with off-network reality shows and hour-long dramas.

Early Evening

An excellent opportunity to counter-program with off-network entertainment is offered during this traditional news block on affiliated stations.

Prime Access

The independent can benefit from audience flow in the 7:00 to 8:00 P.M. period by airing additional entertainment. An alternative for true independents would be to start a two-hour movie at 7:00 P.M. in an attempt to attract adults and hold them during the first hour of network prime time.

Late Fringe