Building Story

Concept Art for Defective Detective by Avner Geller and Stevie Lewis, Ringling College of Art and Design

Basic story structure seems pretty simple:

- It is an ordinary day

- Something happens that moves the character to action

- A character wants something badly

- He meets with conflict

- The conflict intensifies until

- He makes a discovery, learns a lesson, or makes a choice

- In order to succeed.

But storytelling is hard. Each story is unique and has its own puzzles to solve. What gets tricky is figuring out how to raise the conflict, or in what order to place the events of your story to engage and entertain an audience. In this chapter we are going to discuss some strategies that will help you do that.

An audience trusts you to take it on a journey and bring it back safely. What this means is that the audience is expecting an experience. It wants a certain amount of intrigue, engagement, difficulty, problem solving, heartbreak, hope—and even pain with a payoff that makes it all worth the time they spent watching your film.

What happens to the character, the events of the story, is what happens to the audience. The character is really a stand-in for the audience.

As a storyteller you are in service to the audience. Everything you do is for the good of the story to deliver an experience for the audience, move it emotionally and bring it back transformed through the theme, the life lesson.

It’s the hardest thing to remember when you are building a story—that it isn’t about you and what you want—it is about the audience and if what you deliver is a satisfying experience. Will they want to watch your film again?

Pitfalls in the Process

When creating a short some of the biggest pitfalls have to do with two things:

The terminology we use. When we start talking about things like “life lessons” or “delivering an experience that transforms the audience” the tendency is to go to something that is “big” or “important.” Shorts are small. They are single situations, a single conflict, a memorable moment or a slice of life. Sometimes they are just jokes. And a good joke has everything we ask for above.

When a story isn’t working, instead of identifying what is wrong with the story, new shorts producers tend to add more: another character, another event, more props, more dialogue. It usually doesn’t fix the story. It is just more, not better.

Premise and Theme

With most ideas you will start with your premise and your theme. Remember that the premise is one or two sentences that introduce your character and the conflict. The theme is the life lesson that your character and audience learn as it watches your film.

Let’s use Defective Detective as an example:

Theme: Don’t jump to conclusions

Premise: An inept detective wrongly assumes a notorious killer is harming his neighbor.

Defective Detective by Avner Geller and Stevie Lewis, Ringling College of Art and Design

The premise is the first step to see if we have anything interesting to pursue. It is really just a sketch of an idea. It provides the basic framework but lacks details on how that situation will play out.

Who, What and Why? Where, When and How?

If you look at the premise above, all you really have is a situation. It sounds like fun, but we need a little more clarity to really know what we are working with and before we can start.

Usually there is something more than the premise already in the back of your brain. You may have even begun to envision what happens—what the character does. But it will make it easier to build a successful story if you take the time to make sure you know more about the toys you’ve brought to your sandbox and how you think they function. These are the story elements you’re going to be playing with for a while. Let’s get to know them before we use them.

- Who is your character? What does he want? Why can’t he get it? What is at stake?

- Where are we? When does it take place?

- Who are the other characters? What do they want? Why can’t they get it? What’s at stake for them?

- Who is the story about? How does that character arc? What else do you need to know?

In Defective Detective we know that the detective tends to jump to conclusions—that comes from our theme. We know there is a notorious killer who he thinks is harming his neighbor. We know that, since the lesson is “don’t jump to conclusions,” the neighbor is probably not being harmed—or not in the way that he thinks. This is about all we can muster from the premise.

Here are where your questions come in—and it might take a lot of brainstorming to find the answers.

If you have done your initial character profile, you probably know that what is at stake is the detective’s reputation, he acts more out of emotion than logic and that he has some self doubt about his capabilities. We know he wants to save his neighbor. He can’t do that because no harm really exists.

Where and when does the story take place? The characters are neighbors. How do you determine that they live in an apartment and that her apartment is above his? How does he know something is wrong? What does he see or hear? If she screams: what is she really screaming at, what’s the situation and problem in her apartment?

In this story, the detective imagines the absolute worst. And we know that we have to teach him how his assumptions are wrong. So whatever is going on above him needs to be rather mundane. What is something simple that could make an old woman scream? Geller and Lewis came up with a brilliant solution with the mouse. A mouse might also help define the time period, condition or age of the apartments. Wait—how do know his neighbor is an old woman? What type of neighbor would be the most vulnerable and in need of his help?

The scream is probably enough to move the detective into action, but then what? You can’t just scream all the way through your piece. You could, but put that against the experience of the audience—is that building the suspense, or the humor, that you want? If the detective imagines the worst, and we know he thinks the threat is a killer, then the best evidence of physical harm and possible death is blood. What could the old woman be doing that would also give the impression of this type of physical harm? This is how you might begin to think through the questions that will lead you to tomato soup.

Remember that you need to do a character profile for the old woman, too. What kind of personality do we need to teach the life lesson we want to deliver? Using an old woman is great because the detective (and the audience) can jump to conclusions (or stereotypes or generalizations) about her needing help. But if the life lesson is to not jump to conclusions, then you need a character that can take care of herself.

You want to identify as many of your assets as you can before you start building your story, but as you get to know the story better, these may swap out and change.

We still don’t know how the story unfolds but by taking the time to define a few details we have a better understanding of what we are trying to do and how we might do it.

When you have gathered all your toys you can start building your story. The place that you begin—is at the end.

Endings and Beginnings

If you are taking your audience on a journey, you have to know the destination.

How important is this? Did you ever tell a joke and forget the punch line? The whole thing falls apart. In storytelling the ending is everything. If the ending doesn’t work, the story doesn’t work.

This is so important that James Mercurio, screenwriter and teacher, believes that until you know the ending, you can’t really understand how to write the beginning. In order to know your ending you must understand what your piece means—the theme.

This is because the theme or meaning of the piece directs the resolution. In story structure, the theme is realized in the crisis of the story. This is where your character makes a discovery, learns a lesson and/or makes a choice. Whatever your character learns or discovers communicates the theme of the film. The decision he makes, how he chooses to act against the opposition, determines the ending.1

The ending that you are looking for is the transformation of the character, the audience, or both. In the very best endings, you give the audience what it expects, but not in the way it expects.

In feature films the lesson usually happens when the character is at their lowest point. When Shrek sits heartbroken in the swamp, Donkey convinces him to tell Fiona he loves her. Shrek realizes at that moment that he both wants and deserves love (realization of the theme). He goes to defeat Farqaad and win his girl (the act that determines the ending). And quite a bit happens before we get the ending we expect—but not in the way we expect it.

When Fiona finds true love, she is supposed to take true love’s form. Both Fiona and the audience believe that she will assume the beautiful form of the princess—because pure love is beautiful. Instead she turns into an ogre. And she is fine with this because it is the form of her true love. In the film, the audience has known for a long time that Shrek and Fiona will end up together, but this ending does it in such a way that it is both perfectly aligned with the story and unpredictable.

From here we can write the beginning which shows Shrek in his swamp using a fairy tale book with an illustration of Fiona as toilet paper. If you don’t know that Fiona becomes what is highest in Shrek’s esteem you can write this moment that shows when she is at his lowest. It is in these first few moments of the film that you define the arc of the character and begin to lead him to what he needs to learn.

In the short film, as you know by now, we don’t have a lot of time. So when you are defining your ending it is usually a combination of the crisis and the resolution. And in the short, it may not be actually be a crisis—it may just be a pivot that changes the direction of the story or a climax that you have been moving toward. And the character may not have been brought down emotionally—the climax may be a moment of joy that propels them toward the resolution.

Likewise the beginning usually includes both the set up and the inciting moment. The setup is your ordinary day. And the inciting moment is what propels the character into action. These combined begin and define the arc of your character in your piece. Sometimes in a short, you won’t even have an exposition. You get right into the story at the point of action.

At the end of Defective Detective, the detective shuts his eyes and musters the courage to shoot what he believes is the Butcher—the notorious killer—to save his neighbor. What he shoots is a pot of soup that drains onto the floor. And thankfully, he has not shot the old woman. He learns he was mistaken. Because you know this is the ending, in the beginning you have to start with the soup. The detective hears a scream and sees what he thinks is blood—but it is the soup that has been dropped, draining onto the floor above. You can’t set up the inciting moment unless it is tied to the lesson learned at the end. Anton Chekhov says, “If you put in a gun in the first act, you have to use it by the third.” And in this case the “gun” is a pot of soup.

Defective Detective by Avner Geller and Stevie Lewis, Ringling College of Art and Design

So for a story you have to know your ending. Whatever happens at the end has to be set up in the beginning. These parts of the story relate. If your ending isn’t working, the problem is in your beginning.

Building Conflict: The Journey of the Character

We know our beginning, we know our ending, we know how our theme is realized and now we just have to get there. This is where you get to have some fun. Between your inciting moment and your pivot, climax or crisis we have what Brian McDonald calls ritual pain.2 This is where you take your character through enough challenges and pitfalls to allow them to make their discovery and change. And the change makes everything they have gone through worth it. Francis Glebas says during this time the character will toggle emotionally between hope and fear.3 The character will think he can do something (hope) and then he can’t (fear). The emotion is fear because if the character cannot overcome the obstacle, he will fail. The trials that the character endures as the conflict builds is the journey of the character.

Progression of Conflict

Often when beginning storytellers think of conflict, they default to the catastrophic. They think about big problems. Problems don’t have to be very bad to greatly affect us and cause conflict. An itch, the common cold, or a bee sting can all have great effect and be wonderful inspiration for a story. But if you scratch an itch, take medicine, or put ointment on your sting, the story is over. These are single events that cause a problem and can be easily resolved. To build story, the conflict has to get worse. Scratching an itch leads to itching all over that leads to a spreading rash that lands you in the hospital where you meet a pretty nurse who catches your rash …

In story, the progression of the conflict for the character occurs in a pretty predictable way. In the short, most conflicts are what we call compounded conflicts. A compounded conflict is a single problem that builds in layers upon itself through similar or related events.

For example, in Defective Detective, the conflict for the detective is the imagined harm of his neighbor. At the inciting moment he hears a scream and sees what he thinks is a drop of blood. He springs into action (hope) climbing on her balcony when the window is splattered with what he thinks is more blood (fear) but he gets in a side window (hope) and makes it down a hallway where he smells something “dead” (fear) only to choose to turn and shoot (hope) and realize that he just shot a pot of soup (fear). So the compounded conflict is about the perception of increased physical harm—a drop of blood, a large splatter of blood, and finally the smell of death.

Defective Detective by Avner Geller and Stevie Lewis, Ringling College of Art and Design

Increasing the Intensity of the Conflict

One of the common problems in story development is that sometimes multiple events are created for the character to overcome, but the events do not rise in intensity. The story doesn’t really go anywhere.

Increasing intensity has to do with raising the magnitude of a problem in a specific way. Some of these ways to raise the magnitude of the conflict include raising the:

- Physical obstacle

- Physical jeopardy

- Mental jeopardy

- Amount of activity

- Expenditure of energy

- Acquisition or depletion of strength

- Competition

- Degree of completion

- Volume or quantity of the problem or obstacle.

These problems compound as the need for the character to resolve the conflict becomes greater.

The Character in Conflict

The story is the character’s story. The plot is driven not by the action required by the conflict, but by the reaction of the character to the problem. Depending on whom your character is, what their strengths and weaknesses are, their history, moral position and whether they operate primarily from a position of logic or emotion it will cause the character to react to a problem in one of four ways:

The character may react in just one way or in all of these ways as they explore different tactics—ways the character attempts to resolve the conflict. These tactics include:

- Avoiding

- Preventing

- Controlling

- Negotiating

- Attacking.

These tactics are driven by the character’s thoughts and emotions. Thought and emotion drive their action and reaction. Emotion is evoked in the character because there is something at stake for the character. What is at stake for the character usually has to do with loss of status or power:

- Control

- Acceptance

- Reputation

- Freedom

- Self-esteem

- Health.

Emotional changes in the character occur as each event in the story puts what is at stake in jeopardy. These emotional changes are called a character arc. Every character, at every point in the story, is thinking and feeling something. This is called internal monologue. When you understand what the character is thinking and feeling you can determine the most truthful way for the character to react to the conflict. You can also alter the internal monologue by trying tactics to find which are most entertaining to your audience.

If you are having trouble writing conflict events, it is helpful to write out or talk out what the character is thinking. This helps clarify where the story needs to go or identifies when the character or conflict has deviated from the focus of the story.

If you know what your character is thinking or feeling, you also know what they are doing—and the intensity of emotion with which they are doing it. This gives you the weight and force of the action. And when you know this, you can animate the scene.

Narrative Questions and Narrative Structures

By the time you’ve figured out your conflicts, reactions and tactics you probably have your events in some kind of order. This is where you want to see if it is creating the experience for your audience that you want. Sometimes you have all of the elements for a story but it still isn’t entertaining. Often this is because the story is laid out and the audience can see what is coming. It makes it boring. We already know how it will end.

What engages an audience and keeps it engaged is carefully laid out narrative questions. Narrative questions set up curiosity, intrigue or suspense in the mind of your audience. Some questions you will answer immediately—they are setups. For example in Defective Detective the first thing we see is an apartment building when a light in one window is on. Immediately your audience is wondering—who’s in the apartment? And then we can show them. Other times, when answers to the questions are given too quickly the audience loses interest. So the key to good storytelling is to make the audience wait. But it is also important to determine what it is waiting for.

In any story, your audience will be located in one of three places:

- With the character. The audience learns as the character learns. This creates suspense. Neither knows exactly what will happen.

- Ahead of the character. The audience knows more than the character. This creates tension and drama. Think of the classic horror film where the audience is screaming at the character, “Don’t open the door!” This location of the audience can also sometimes create humor—usually when the character is inept or clueless to the real situation that is going on around him.

- Behind the character. The character knows more than the audience. This creates intrigue and curiosity and those lead to surprise.

Where the audience is located in relationship to the character changes the journey for the audience.

For example, when we looked at the rising conflicts in Defective Detective, we only looked at the conflicts that the detective was facing. This could be the story and all that we see. If that were the case, the audience would be located with the detective and completely believe that his neighbor is in peril. The story is a drama.

If we go this route, the audience will be asking if the detective will get there in time and if the neighbor will be saved. After all that suspense, is the ending satisfying or will it fall flat? Will the detective learn his lesson?

Is there more information that the audience needs to know that will make the story more entertaining? When we add the additional story of the neighbor, we now place the audience ahead of the character. The question that engages the audience through the story is: What will happen when the two meet? The audience knows the old woman is safe so each time we raise the conflict we create humor by his reaction instead of drama. And the ending works better because he finally knows what we know. Geller and Lewis take this one step further in an epilogue to the story. While the detective and old woman eat soup, we pull out to discover two things: the old woman is in control, and that her apartment is nearly the only apartment where a crime is not being committed. The detective is not so inept after all. This unexpected epilogue puts the audience behind the character and the story giving it a moment of discovery.

Defective Detective by Avner Geller and Stevie Lewis, Ringling College of Art and Design

The order of the events in your story determines where your audience is located and how it moves through the story.

In feature films, where the audience is located varies through the different events of the story. In the short the audience is usually only in one place. Think about where you want it to be.

The audience will think and feel something at every event in your story. What it is thinking and feeling is called the external monologue. This can be the same—or in opposition to—what the character is thinking and feeling—the internal monologue. By writing exactly what you want your audience to think and feel through the events of your story, you can pinpoint, construct, and evaluate your narrative questions and edit the order of your events to guide (or move) your audience through the story, what you want it to know, where you want it to be and how you want it to feel.

Thankfully, there are a few standard story structures against which you can put your events to help find the most entertaining and engaging journey for your audience. Often—not always—the structure you want relates to the lesson you want your character and audience to learn.

Linear Narrative

This structure is the one that we find at the beginning of the chapter. In the short, this is the closest approximation of the Hero’s Journey commonly used in most feature films. In a linear structure, the arc of the character tends to move from one extreme to another. What the character learns or where he moves to by the end of the film is in contrast to or is the opposite of where he started out. For example, Shrek thinks he likes being alone but finds out he needs and deserves a love and friends.

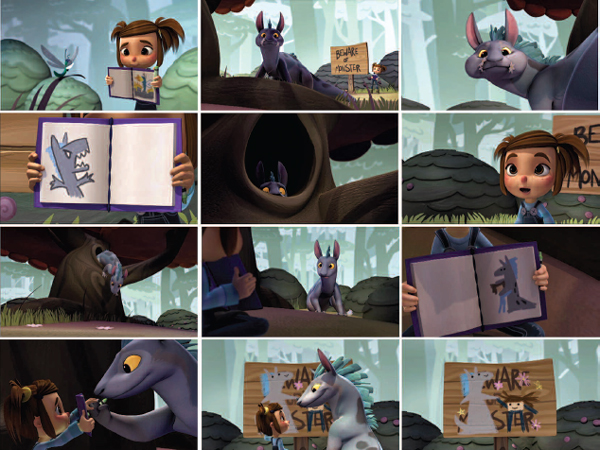

Beware of Monster by Meghan Stockham, Ringling College of Art and Design

The short, Beware of Monster, largely follows this structure:

Theme: Sometimes what you think is a monster is really a friend.

Premise: An adventuresome young tomboy finds a monster and must convince it that she is really a friend.

- It is an ordinary day: A little girl who likes monsters goes out every day and finds something—an insect—and draws a picture of it in her sketchbook looking ferocious, and shows it the picture. It is scared away.

- Something happens that moves the character to action: She comes across a sign that reads, “Beware of Monster” and looks around with great anticipation.

- A character wants something badly: She wants to meet a monster.

- He meets with conflict: She sees one eating flowers, but when she giggles, she scares it into hiding.

- The conflict intensifies until: Because she is standing beside the sign, the creature thinks she is the monster. To clarify matters she draws him as ferocious—and it scares him more.

- He makes a discovery, learns a lesson, or makes a choice: She gets an idea.

- It is at this point that the little girl figures it out. Drawing creatures as ferocious scares them. She has to change her method if she is going to make a friend. Remember however, that storytelling is story delaying, so instead Meghan Stockham has her little girl lure the creature out with his favorite food—flowers. And she even draws him one—but it doesn’t taste very good.

- In order to succeed: When the creature is close enough she shows him a new picture—one of her hugging him.

At this point Stockham could end the story with a hug. But remember what we said about props—if you put a gun in Act One … —so we need to get back to the sign.

As part of the resolution, the little girl shows the monster how to draw so he can respond in kind. The last image is back at the sign. Together they have made a drawing over the words that shows us (not tells us) that there are no monsters, only friends.

In this film, the audience learns as the character(s) learn.

Other films that use linear structure are:

- Dancing Thief: A jewelry thief gives up both his treasure and his freedom in exchange for a dance—and through dance he also finds love.

- Fantasia Taurina: A bull is mad when a girl steals his apples but learns he needs her when he gets in a crisis.

- The Kite: A little creature tries again and again to fly a kite, only to learn that when it flies too well, he has to let it go.

- Noggin: A mutant and outcast in a world of Bellyfaces learns that being different is really a gift.

Parallel Structure

With parallel structure, more than one event is going on at the same time during the story. Usually these events eventually converge at the crisis or the climax. In this structure the audience is ahead of the character. Because it can see both simultaneous events, it knows more than any individual character. The primary narrative questions involve wondering when and how the character(s) will find out what the audience already knows. This structure is often used in horror films or mysteries creating suspense; it is often used in scenes with high action like car chases; and it is sometimes used in comedy—in all of these situations the main character doesn’t know what is really happening, but the audience does.

Defective Detective by Avner Geller and Stevie Lewis, Ringling College of Art and Design

Clearly our primary case study in this chapter, Defective Detective, follows this structure. When we enter the story, the audience is with the detective. We too believe the drop of “red” is blood and something horrible must be happening upstairs. But very quickly, we learn that the old lady saw a mouse and dropped her pot of soup. The questions that drive the story next are:

- When will the detective find out he is wrong?

- Will the old lady kill the mouse?

- When she does and the detective thinks he smells something dead—will he actually harm the old lady in attempts to stop the killer?

- And finally—did he learn his lesson?

The attempts of the old lady to kill the mouse are perfectly timed to propel the detective forward in his quest.

Another short that uses parallel structure is:

- Ritterschlag: A young dragon has been in training to kill knights. While his trainer sleeps, he tries to do this on his own.

In this structure, the character moves back and forth between similar but escalating obstacles and similar attempts at resolution. Often the obstacles are new characters, objects or challenges that arrive as the old ones leave.4 The difference between this structure and a parallel structure is that the events are not happening at the same time but in sequence, like a card game. The events do usually converge at the pivot, climax or crisis. These stories frequently involve competition, cause and effect or conversations. Games of strategy like poker or war where one side delivers and the other responds are also a common use of this structure.

Bottle by Kirsten Lepore

Bottle is one example of this structure.

Theme: Friendship is worth the risk.

Premise: A snowman and a sandman become pen pals and decide to meet.

On the surface you might think that this is a parallel structure but the events in the story are not happening simultaneously. Instead the sandman finds a bottle of snow, and sends one back out with sand. Then the snowman receives it. The snowman sends out a bottle, and the sandman receives it. The events ping-pong back and forth between the characters in conversation. The characters in this piece come from very different environments that neither could ever hope to visit and survive. In the bottle, they send objects from where they live. So the narrative questions have the audience asking, What will be sent next? And how will that strange object be interpreted?

In Gopher Broke, a gopher digs holes in a road, causing a Produce Truck to bounce, and making vegetables fall from the truck. Each time the gopher successfully gets vegetables on the ground, some other creature steals them before he can get to them: first a squirrel; then a mean chicken; and finally a flock of crows. Each event sends him back to try again. He ping-pongs between the same attempt to get vegetables and similar but escalating defeats. The narrative question in this piece is, Will the gopher ever get some vegetables and, once the pattern is set, What will be waiting to eat them at the next stop?

In this structure, the audience usually learns as the character learns. Narrative questions involve what will happen when we try again.

Other shorts that follow this structure are:

- A Great Big Robot from Outer Space Ate My Homework: A boy tries to explain to his teacher that his homework was eaten by an alien robot, but at each explanation the teacher misinterprets what he is describing.

- Poor Bogo: A storybook creature tries to act out what is in the imagination of a child as her father tries to end the story and get her to go to sleep.

Circular Structure

In a circular story structure, the character ends up back where he began. Sometimes he changes and sometimes he doesn’t. This structure is commonly used for serial cartoons where, at the end of the day, the hero must be restored to himself to start another adventure tomorrow. Roadrunner, Scooby Doo, Tom and Jerry, and Ben 10 go through a series of adventures in every episode. These characters may arc within the episode itself, but by the end, they are essentially unchanged.5 Lion King is a feature film that uses this structure—it is even reflected in the main theme of the movie. This is often the case.

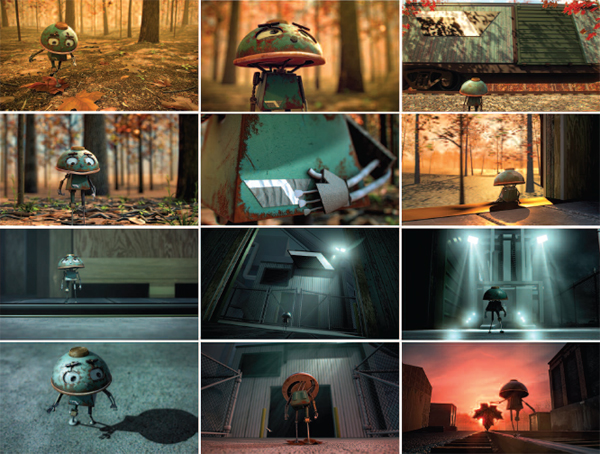

Origin by Robert Showalter, Ringling College of Art and Design

Origin is an example of a short that uses the circular story structure. And look at the theme.

Theme: Where you are is where you need to be.

Premise: A small robot takes a journey to find out where he came from.

In this story a small robot skips happily on leaves in a colorful forest. He’s happy, but has a longing to know where he came from. One day he gets that opportunity and hops on a train to visit that place. What he finds is a place that is monochromatic, mechanical, cold and unfriendly.

Pivot: As the character backs away from the cold environment he steps on a leaf on the ground.

As he turns toward the light of the forest we see him remember. He picks up the leaf and begins his journey back to where he originally started and again, he is happy.

In this structure the audience usually learns as the character learns. Sometimes the audience will be ahead of the character where it knows more than the character knows.

In Our Special Day a little girl is waiting for her father to come and pick her up. She’s all dressed up, her bag is packed and her favorite doll is ready to accompany her on her trip. She waits all day. She sits on the steps, she swings on a tire swing, she pulls petals off flowers—he loves me, he loves me not— when she hears a car coming down the road. It’s not him and she ends up sitting on a fence at sunset waiting. “I don’t know where he is, but I know he’s out there.”

Other shorts that use this structure are:

- Eureka: There is more than one way to solve a problem.

- The Animator and the Seat: There are no breaks at crunch time.

- Catch: Stay a child as long as you can.

Bus Stop Structure

Stan Howard, animation writer, describes this structure as one where an essential secondary character arrives and leaves during various parts in a story. “It is a bit like people getting on and off a bus.” The example he gives is Cinderella’s godmother, who arrives, solves a problem and leaves.6 In addition these characters might also arrive to deliver a message. In Shrek, the mirror on the wall serves this purpose. He introduces Fiona as just one among the classic fairy tale princesses that we already know.

Das Floss, directed by Jan Thuring, Filmakademie Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany

Das Floss is a short where a seagull plays this role but here he creates a problem. Two men have been adrift on a raft at sea for many days. They watch as a seagull catches a fish and lands on their mast to eat. The seagull drops the fish onto the raft causing conflict for food between two hungry men and then flies away. Because they can’t share, the conflict leads to the demise of both men.

In all of these examples, this character is used to move the story forward. You want to be careful about introducing a new character at the end of your story that solves the problem. This is usually not your best ending because the life lesson is—usually—imposed by this character instead of having your other character(s) learn through the trials of the story. This character has not experienced any pain.

If you are doing 3D animation you will want to make sure this character is essential—that there is no other way to propel the story—because you will have to model, rig and animate another character for just a few seconds of screen time.

With bus stop characters the audience is learning or discovering with the main character because it rarely sees these other characters coming. But these characters always create a pivot and change the narrative questions to something like—What now? Which one? Where is that going to take us? Or as simple a reaction as “Uh oh!”

Slice of Life

This story structure is used when the situation doesn’t appear to have a lot of conflict, when the problem seems inherent in the story.

Treasure by Chelsea Bartlett, Ringling College of Art and Design

Chelsea Bartlett’s Treasure is such a story. In this film a homeless woman is living in a junk yard. She is rifling through the refuse looking for items of use or value to her. She seems pretty happy. Other than her inherent situation, there isn’t a lot of conflict. We watch as she searches through items, picking some up and keeping them and putting others back. The story question for the audience becomes, Why is she being so selective, and what is she going to do with what she chooses? At the pivot of the story she finds a diamond ring. We think that that she has finally found a treasure of real value. And from her reaction, so does she. But we find out that in this world, the diamond has no monetary value—at least not to her. It is just the item in her collection that will help transform her tent into a beautiful place. We learn that happiness is not about what you have but what you do with what you’ve got.

In Robin Casey’s Flight of Fancy, again we have a story where the only problem is that a young debutant is getting ready for a dance and refuses an offer for a ride. The only real question here is, How will she get there?—which turns out to be a little bit of magic involving a flock of bluebirds who fly her there, and her gratefulness to them for the ride.

In the slice of life structure the audience is almost always behind the character. The character knows more than the audience. As we enter, they already have a plan. The story is almost always propelled forward because the audience wonders exactly why they are doing what they are doing and the life lesson is learned when we find out.

Flight of Fancy by Robin Casey

There is no magic formula for making a good story. Good story is a combination of a strong character and the appropriate choice of structure, conflict, emotion and reaction for that character. Knowing the options allows the storyteller to experiment, search and find the best way to tell the story.

When building story, remember:

- The goal of storytelling is to create a satisfying experience for an audience.

- Stories begin with a premise and a theme.

- To flesh out your ideas, ask questions: Who, what, why, where, when and how.

- When you begin to build your story, start with your ending.

- Beginnings and endings relate. The beginning is really just the ending in the form of a question. If your ending doesn’t work, the problem will be in the set up.

- Most shorts have compounded conflicts.

- Conflicts in a story need to intensify.

- The character in conflict will try different tactics to resolve the conflict. We watch a character to see how they will react under pressure.

- The reaction of the character to the conflict is driven by thought and emotion. This is called internal monologue.

- The audience is also driven by thought and emotion. This is called external monologue.

- Your audience will be located in one of three places in relationship to your character: ahead of the character, where it knows more than the character knows; with the character, where it learns as the character learns; or behind the character, where the character knows more than the audience.

- The audience is led through the story by a series of narrative questions.

- The location of the audience in relationship to the story determines what questions the audience is asking.

- You don’t want to answer story questions immediately. To engage the audience you have to make it wait.

- There are a few standard story structures that are often determined by the type of story you are trying to tell and the type of life lesson your character learns:

- Linear

- Parallel

- Zigzag or Ping-pong

- Circular

- Bus Stop

- Slice of Life.

- Successful storytelling requires the exploration of possibilities until you find the most entertaining way to tell the story.

Additional Resources: www.ideasfortheanimatedshort.com

- See additional information for story development in the Case Studies.

- See also Designing for a Skill Set, with interviews from the creators of:

- Flight of Fancy

- Treasure

- Bottle

- Origin

- Beware of Monster

- Defective Detective.

Recommended Reading

- Brian McDonald, Invisible Ink

- Francis Glebas, Directing the Story

- Robert McKee, Story

- Jeffrey Scott, How to Write for Animation

- James Mercurio, Killer Endings (DVD)

Notes

1 James Mercurio, Killer Endings, DVD, Screenwriting Expo Seminar Series #027, Creative Screenwriting Publications, Inc., Los Angeles, CA, 2006.

2 Brian McDonald, Invisible Ink, Libertary Edition, Seattle, WA, 2010, p. 55

3 Francis Glebas, Directing the Story, Focal Press, Elsevier Inc., Burlington, MA, 2009, p. 275

4 Stan Howard, MakeMovies: AnimationScriptwriting. http://www.makemovies.co.uk/. This structure is not a new idea, but I have not found the term “zigzag” used in any other source.

5 Stan Howard, MakeMovies: AnimationScriptwriting. http://www.makemovies.co.uk/.

6 Stan Howard, MakeMovies: AnimationScriptwriting. http://www.makemovies.co.uk/. This structure is not a new idea, but I have not found the term “bus stop” used in any other source.

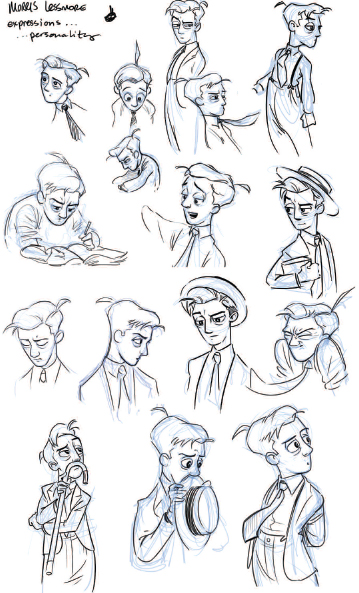

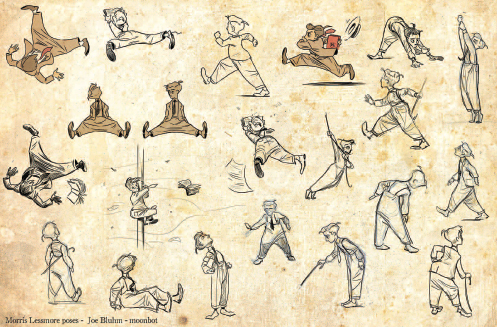

Making It Visual: The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore

An interview with Brandon Oldenburg and Adam Volker, Moonbot Studios (excerpt)

Brandon Oldenburg was a co-founding member of Reel FX Creative Studios (1995), doing a combination of design and special effects for television and film. Serving as Senior Creative Director for 15 years, he worked with such clients as Troublemaker Studios, Pixar, Disney, DreamWorks and Blue Sky Studios. From 1998 to 2009 Mr. Oldenburg oversaw a joint venture with William Joyce and Reel FX. This working relationship led to the creation of Moonbot Studios in Shreveport, Louisiana, which Oldenburg and Joyce co-founded in 2009. Their first animated short, The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore, won a 2012 Oscar for Best Animated Short.

Adam Volker is an illustrator from the Midwest. He studied illustration at the Ringling College of Art and Design and got his start as a concept artist in the video game industry. He has worked on multiple AAA titles for companies such as EA Tiburon, Bioware, and Midway Home Entertainment. In 2009, Volker moved to Shreveport, Louisiana, to work with William Joyce on a series of children’s books. He transitioned into art direction on Moonbot’s first short film, The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore, and has been a story/concept artist for the studio for several years. Volker is now a creative director at Moonbot’s fledgling Moonbot Interactive branch. He still draws in his sketchbook whenever possible.

Q: How much does Buster Keaton influence the character development of Mr. Morris Lessmore and the way that he does things?

Moonbot: A lot! There is almost a one-to-one influence. For instance, there was a rule about his eyelids, that his eyes would always be half-lidded on the top. Like Buster Keaton, Morris is a silent character, so his physicality and emotions have to tell the story. We almost took the mouth out of him totally so that he was emoting only with his eyes, and poses, instead of his mouth.

Q: It seems like that means you would have to become more creative visually. How do you come up with some of the visual things that Morris does?

Brandon: It comes from a lot of thought about each particular interaction or moment in the story. What would that moment mean to Morris? For instance, Jamil [Lahham] went through a lot of paces with his guys about the way Morris would run, or the way Morris would turn a page, or the way Morris would sit, instead of having just somebody sit down and make the pose appealing. It had to be specific.

For example, in the hurricane scene there is a moment when Morris is being swept away and he catches his cane on the light post. He holds onto the cane with his teeth as he watches his book hanging on a wire. The cane in the teeth was one of those moments. We had to make sure that it was Morris’ teeth that were biting on the end of the cane and not just anybody’s teeth … or that even he would do that.

We took the things we liked from Singing in the Rain or The Wizard of Oz and translated those to Morris’ actions. We knew we had a storm, and mostly it was the fun of trying to wedge those moments in. How could we put in a light post in the city and have it blow away? Let’s try this, and let’s try that. We would board and re-board until it read right.

Sometimes the moments weren’t even in the script or the animatic per se. They became the sort of thing that just occurred in reviewing the animation performances.

Adam: Right. Another time is when the storm is over and the house lands upside down, the door opens and Morris tumbles out. Then his cane comes down, his hat floats to his head and then his book drops in front of him. I did the storyboards for that and they were atrocious. Really the reason that moment works is because of the animator—Bevin (Blocker)—did the fall. And that’s why that moment is so appealing to watch. Someone was given the freedom to express whatever they wanted— not what I boarded out—but how they felt it should go. And Bevin made it way better.

Not only that, but the over-the-top fall contrasts really nicely to the quiet moment when Morris realizes that his book is empty. The fall gives you an “up”—a small lift—in the middle of a catastrophe.

Q: There is another scene later in the film when Morris is in the library fixing an older book. In that scene there is a montage where Morris flies through a series of letters. Can you talk about that, and the use of letter gags throughout the film?

Moonbot: Using the text was a thematic decision. We knew we were trying to tell a story about books and about words, so every little idea we had about what would be in a letter-themed world— that would be in a word-centric world—we tried to inject it. So there are letters on some of the clothes of the characters, and the books eat alphabet cereal in the morning. We also toyed briefly with Morris having a letter too but as we thought about it later, that became a bit too contrived and it gave away where he was going too directly.

In the medical scene montage, there was just something appealing to us in the graphical sense of just how beautiful letters are when they are taken out of context. How beautiful is a question mark, right? It’s a beautiful shape. And you can think of letters in terms of objects or actions. An “S” is like a slide.

We were trying to capture what it is like to get sucked into a story. For production reasons, we didn’t have Morris go on a journey between stories, landing on a pirate ship and flying over a castle, only to find him somewhere else. We actually had boarded that a long time ago. It could have been beautiful but also difficult because of all the environments you would have to build. We thought the simplicity of using only words just seemed like the right thing. We were able to create a visceral, adrenaline-rushed flight through the words for Morris. And it was also a very happy accident in that it was very simple to build.

Q: What advice would you give for first-time filmmakers?

Brandon: Your craft needs to be good (that is something you could spend hours and hours learning), but you really have to tell a story that is true. And if you can have at least one true moment in your story, then it’s going to be good. Then you can ride on that for a while. That’s really the most important part I think.

Some people called it heart, some call it character. I think it comes from speaking from something that really resonates inside of you, something that you personally experienced. And that’s what you can latch onto. This particular show was good enough to have so many things that we could latch onto even if we were not all around for the initial nugget of inspiration. The curative power of story was really big.

Additional Resources: www.ideasfortheanimatedshort.com

See a complete case study of this piece under Case Studies on the web:

- Character and Environment Designs

- Scene Clips

- The Making of The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore