Acting: Exploring the Human Condition

The Songs of Jacques Brel, Photo Courtesy of Florida Studio Theatre

The Kite by Gwynne Olson-Wheeler

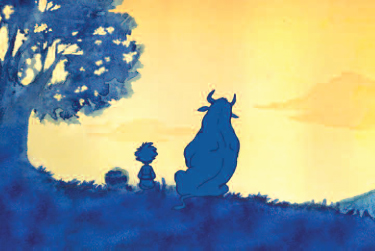

Animators are actors. They create every nuance of a performance and breathe life into each character that they animate. The very essence of their art embodies the root of the word animation—anima, which in Latin means breath of life. Kathy Altieri, Production Designer at DreamWorks Feature Animation, explains it this way:

When you’re an artist, you have to feel and experience what you’re trying to draw.

For example, if I’m drawing a figure, I need to feel the weight of her hip on the chair. I need to feel the pull of her waist as she twists. It has nothing to do with the external shape, it has to do with sympathy for what the model is doing and feeling, and how that affects the line that comes out of my hand. In animation, it’s all about getting the audience to feel a certain way. We do this in every department, through music, lighting, color and line. The animator has us in his powerful grip. If he can feel what his character is feeling, he will communicate that through even the smallest movements his character performs. He quite literally becomes the actor portraying the role. The more fluent he becomes at acting himself, the better his character will communicate to us, the audience, and the more we will feel what we are supposed to feel at any given moment in the film.

Acting is truth. This is an adage in the acting world. It means that every moment in your story must be imbued with the emotional intensity of life itself. Whether you are creating a man, a child, a teapot or a lion, character is created by the pulse of true emotion. Like Geppetto breathing life into Pinocchio, you must bring the vividness of authentic emotion into your work. In this chapter you will learn how to create this truth in your work. You will learn a simple acting technique that will teach you:

- How to develop a character’s inner life:

- How thought creates emotion

- How emotion creates gesture.

- How to develop a character’s outer life:

- How a character is further defined in the scene by specifically identifying the Objectives, Intentions, and Tactics.

Additionally, by studying the art of acting you will learn to:

- Use the tools of Emotional Recall and The Magic If to “get inside” your character and avoid creating cliché expressions and gestures

- Understand and create characters that are different from you, the animator.

Ultimately, by learning and using an acting technique during the animation process, you will be able to create believable characters that will capture and move your audience during every moment of your film.

Acting I: Technique

Prelude to a Kiss, Photo Courtesy of Florida Studio Theatre

The Dancing Thief, by Meng Vue

At the turn of the twentieth century, Russian actor Constantin Stanislavski—the father of modern acting— discovered how an actor could access human emotion and express it onstage to an audience. He found that when preparing to build a character one must first develop the inner life—the emotions, thoughts, and gestures—that makes that specific character become alive and real to the audience. Therefore, Stanislavski developed a method, called the Theory of Psycho-Physical Action, through which an actor could create the inner life, or emotional core, of any character by employing two elements:

- The Psychological Mind: The images in our brains that create emotion

- The Physical Body: The gestures and movements that reflect the images in the psychological mind.

By utilizing these two elements you will be able to think, feel, and move like your character; and eventually, you will be able to make stronger, emotionally active choices that reveal the character’s development in your story.

We will begin the actor training process with exercises that focus on each element separately. We will then put the two elements—Psychological Mind and Physical Body—together, for then you will see why and how both must be present to create authentic characters.

Element 1: Exploring the Psychological Process

Proof, Photo Courtesy of Florida Studio Theatre

Fox Cry, by Gary Schumer

An actor must learn to create authentic emotion. The internal emotions are the underground current in the psyche that informs all the body’s physical action. For example, when you feel good or happy, your body is open, loose, jaunty. You walk with a swing in your step and your voice has more music in it. When you are sad, every movement is heavier, slower and ponderous. You are burdened with your inner life. Psychology and movement are one. They are reflections of each other. A good actor learns how to create authentic emotion.

To create emotion, an actor can use the following techniques:

- Emotional Recall: recalling memories or past experiences

- The Magic If: imagining yourself in the given circumstances.

In this section you will learn which psychological technique you’re comfortable with. Let’s begin.

Images in the mind create emotion. Imagine that at any moment of the day there is a film in your mind that continuously runs and creates pictures. These pictures, in turn, create emotion.

Example #1: You broke up with your girlfriend or boyfriend. You’re at a café having coffee with friends, but the whole time you’re daydreaming about the past—when you first met, a gift they gave you, a special song you share. You begin to miss your ex terribly and can only sit there twirling your coffee spoon. In fact the whole day or week is spent recalling your relationship, the moments you shared with friends, the fear you feel telling people about the break up, the desire to call. Every moment of your life is imbued with these memories moving like a deep current under every action. The simple tasks you do, drinking coffee, doing homework, eating lunch seem to be burdened by the sadness of your inner conflict. This “current” of emotion created by the images of what we are thinking is called our inner life. Every character, every person has this inner life. It is the replaying of these memories, or the reel of film, in your mind that creates the flow of emotion.

The Magic If: imagining yourself in circumstances. The process of imagining an unknown experience is what Stanislavski called The Magic If. What would I do “if” I were in this circumstance? Like Emotional Recall, mental pictures or thoughts bring about the opportunity to explore The Magic If and empathetically experience the character’s situation.

Example #2: Your character is a superhero and is frightened because he must jump off a building to rescue someone for the first time. You personally have never experienced a situation like this; however, you have experienced the emotion of fear. You must imagine everything you would see in this situation and how it would feel. If you stepped to the edge of a ledge and saw the street racing below, would your heart begin to race and your knees go weak? If you leaned forward and saw the great height from which you could fall would you begin to sweat or feel a sense of desperation?

Theater artists use and remember every moment of their lives whether it’s the pride of a friend’s graduation or the fear they have experienced walking down an unknown street at night. They remember every funny look someone gave them at a party, every surprised reaction in their life. They think, “I must remember this and use it!” They also spend time imagining what it’s like to “walk in someone else’s shoes.”

A fantastic illustration of using one’s personal life as the flesh and substance of art can be found in the true experience often humorously relayed in the classroom of Billy Merritt, a Pixar Animator from 1996 to 2006 and current faculty member at Ringling College of Art & Design.

I recall a day earlier in my career, while working on the film Finding Nemo, when I walked into a fellow animator’s office to say hello and something strange struck me. Everywhere I looked, in all directions, there was a picture of his very recent ex-girlfriend. You couldn’t turn your head without seeing her sublime face in a close up or the two of them together in happier times. I cautiously asked how he was, making small talk but the vibe was palpable. I nonchalantly backed out and ran over to another office saying, “Whoa, I think he’s cracking up, we gotta get him outta there or something, there’s pictures everywhere, it’s not good.”

My friend said not to worry, that he was working on that heavy scene when Marlin believes Nemo is dead and he’s walking away from Dory, essentially breaking up their relationship. The scene for Marlon is about solitary grief and for Dory it’s about parting ways and the loss of a person who makes you feel more complete. It’s a truly beautiful scene inspired by honest emotion.

Similarly, actors continuously observe life around them. While in the park, they look at an elderly person sitting on a bench or a child at play and ask, “What would it be like to be them?” Even mischievous squirrels racing through the trees hold a particular fascination for the actor. For an actor, using images derived from Emotional Recall or The Magic If will unlock what a character is feeling in a specific situation.

The Actor’s Toolbox: Generating Emotion

In the next few exercises you will explore both techniques: Emotional Recall and The Magic If. The exercises will help you learn how to generate authentic emotion. Sometimes Emotional Recall will serve you best to express a character. Sometimes it might be a better choice to use The Magic If or empathy. Sometimes both work. Now it’s your turn to explore. You will need a chair and a quiet room. Afterwards, you can record your observations.

(*Special Note: view the companion website to see an example of these exercises in action.)

Exercise A: Generating the Emotion of Love. Sit in a chair and make yourself comfortable. Close your eyes and imagine someone you love. Pick an image of that person. You may use:

- Emotional Recall: the memory of a loved one

- The Magic If: an imagined future love.

Think of them specifically: the color of their hair, the way their lip curves, something they have said to you, and when you last saw them. Let the images get deeper within you. Let them flow. The images should create a flood of feelings for this person that you love. Observe these feelings.

Observe:

- How do these feelings move through your body?

- How does your heart feel?

- Does your pulse quicken?

- How does your face change? (the curve of your mouth, the muscles in your cheeks)

- How does this feeling affect your hands? Your feet?

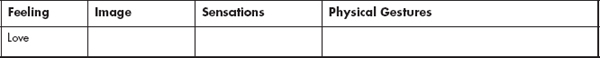

Sample:

Feeling |

Image |

Sensations |

Love |

Grandmother |

Flood of warmth; heart muscles relaxed |

Feeling |

Image |

Sensations |

Love |

Repeat this exercise focusing on the love of a different person—a grandfather, a child, a sister.

How do the feelings change or intensify within your body?

Exercise B: Generating the Emotion of Anger. Sit in a chair and make yourself comfortable. Close your eyes and imagine someone you have a conflict with. Just as in Exercise A, think of them specifically until you have a flood of feelings. Notice whether it’s easier for you to use Emotional Recall, or The Magic If.

Observe:

- How do these feelings move through your body?

- How does your heart feel? (hurt or tight)

- Does your pulse quicken?

- How does your face change? (furrowed brow, muscle tension)

- How does this feeling affect your hands? Your feet?

- Do these feelings make you feel constricted? How do they affect your body?

Record your impressions.

Feeling |

Image |

Sensations |

Anger |

Trying Out Other Emotions. Experiment with different feelings. There are many kinds of loneliness, many kinds of joy. Emotions, like the colors you choose on an artist’s palette, have different shades. In addition, some artists have difficulty “naming” feelings and pinpointing individual emotions that translate to their Psycho-Physical work. For example, someone may say “I’m feeling bummed out” or “I feel low.” But this general feeling has many specific expressions including loneliness, sorrow, or frustration. The good actor, the good artist, is very specific in her choices. Like an accomplished violinist or a painter, she can play an infinite amount of notes or combine an array of colors to achieve a fresh, authentic interpretation. By utilizing this exercise, you will learn to incorporate authentic emotion in your work and also name emotions that might be challenging for you to reach.

Record your impressions and remember to be specific with your images.

ACTING NOTEBOOK FOR ANIMATORS |

||

Feeling |

Image |

Sensations |

Love |

||

Anger |

||

Loneliness |

||

Jealousy |

||

Embarrassment |

||

Fear |

||

The Actor Trap #1: Avoid Cliché!

Cliché Sad, Emotionally Filled Sad, with actress Christianne Greiert, Photos by Maria Lyle

New artists will sometimes show cliché emotions. For example, when asked to portray an emotion, they will smile widely to show happy, or they will frown deeply to show sad. Using oversimplified external expressions that are crudely portrayed will not convey emotion. The result? A generic and empty character who will not impact your audience. Always infuse your character with authentic emotion.

Building a Character: Applying the Psychological Process

Grimmy by Mike Peters

You now know how to access an authentic feeling using Emotional Recall or The Magic If. Now, apply it to a character that you are developing. Whether the character is a vengeful chair, a rambunctious bull, or even Hamlet:

- Find the moment you want to express

- Use your acting technique to feel the corresponding emotion

- Observe how the emotion affects you

- Transpose this emotion to the character.

For example, an actor is studying Hamlet. He knows that Hamlet is consumed by revenge due to the wrongful death of his father. However, the actor has never experienced the death of his own father. How does he emotionally connect to Hamlet? Instead of playing the amateur idea of Hamlet as a crazy madman, the actor looks at each moment in the play and identifies what Hamlet is feeling. Then, by using Emotional Recall and The Magic If, he chooses images from his own life so that he can relate to the character’s specific emotional moments. Thus, he can begin to fathom the depth of Hamlet’s pain.

Remember—be specific to the moment that you want to express.

- Amateurs—project generalized feelings that do not correspond to the moment

- Trained Professionals—convey feelings specific to the moment.

Element 2: Exploring the Physical Gesture

Ethel Waters: His Eye is on the Sparrow, Photo Courtesy of Florida Studio Theatre

A Great Big Robot from Outer Space Ate My Homework, by Mark Shira

The body is the counterpart of the mind. Whether we are gently combing our hair or slamming a door, every physical gesture we express reflects our emotional state. For example, a first-time offender on trial who is trying to appear calm but nervously taps his pencil reveals the truth of how worried and anxious he is, whereas the physical expression of a hardened criminal who methodically taps his pencil, perhaps biding time as he awaits his expected sentence, reveals a different emotional state. In turn, a first-time father who is trying to appear calm while nervously tapping his pencil in a hospital waiting room, is also anxious, but in a completely different way. Yet in all instances, the physical gesture of tapping the pencil is colored by the emotional state of the character. The great Charlie Chaplin knew and embodied this principle whether he was holding out a flower for his love or stepping out of the way from being run over by a car. Emotion and physicality are intertwined. One cannot exist without the other.

Emotion, like a current of electricity, informs every gesture—every movement of the body. Using what we have learned in Element 1, you will now carry out exercises designed to explore how emotion influences the body. You will need a chair and a book.

The Actor’s Toolbox: Exploring Physicality

Exercise A: Exploring the Physicality of Love. Sit in a chair and make yourself comfortable. Hold the book. Using Emotional Recall or empathy, select an image of someone you love. Again, think of them specifically: the color of their hair, the way their lip curves, something they have said to you, and when you last saw them. Let the images get deeper within you. Let them flow. The images should create a flood of feelings for this person. Observe these feelings.

(*Special Note: view the companion website to see an example of these exercises in action.)

Observe yourself while sitting in the chair. How does your body feel in that chair? (languid, relaxed, comfortable).

Pick a gesture:

- Curl your hair.

- Tap your foot.

- Twist a necklace.

Explore the tension in your muscles. Observe the tempo of your tapping.

Now, rise and walk across the room, carrying the book with you.

Explore how these feelings inform how you carry the book. Is the book held closely? Gingerly?

Observe your walk. How do you walk? Long strides or short? Dreamy or slow?

Observe how relaxed or excited you are.

Sample:

Record your impressions.

Exercise B: Exploring the Physicality of Anger. Sit in a chair and make yourself comfortable. Hold the book. Using Emotional Recall or empathy, think of an image that makes you angry. When you have a flood of feelings, begin to observe your physicality.

Observe yourself while sitting in the chair. How tense is your body?

- Curl your hair.

- Tap your foot.

- Read a book.

Explore the tension in your muscles. Observe the tempo of the tapping.

How does it differ from love? Does the tap change into a stomp?

Observe how you hold the book. Do you grip it? What do your fingers feel like?

Now, rise and walk across the room with the book. Observe how the feelings of anger inform how you carry the book. Is the book held closely? Do you throw the book down?

Observe your walk. How do you walk? Long strides or short? What is the tempo?

Observe your posture. Is it tense? Slumped?

Record your impressions.

Trying Out Other Physicalities. Try out other movements and gestures. As we discussed, there are many kinds of feelings and each informs the body in a different way. Observe yourself in your daily life. Observe your mood and how it is reflected in your gestures at the checkout counter, walking to class, or taking a test. By incorporating this exercise you will learn to inform the physical characters you create with the specific emotional reality of their situation.

Try sitting at your desk and writing a letter to someone you are:

- Excited about

- Fearful about

- Hurt by

- Worried for.

Try pacing in the doctor’s office waiting room while feeling:

- Bored

- Anxious

- Frustrated.

Record your impressions and remember to be specific with your images.

Actor Trap #2: Only Using One Element Results in False Acting

Image without a Gesture, Gesture without an Image, Image and Gesture, with actress Christianne Greiert, Photos by Adam D. Martens

Often new actors will mistakenly use only one element, either psychological or physical, which will result in “false” acting. They will solely portray an emotion without any physicality, or only show a physical gesture without emotion. For example, if a director instructs a student to “act scared” and then he or she chooses to act “scared” by shaking their body nervously and bugging out their eyes, the performance will be a cliché of acting—an empty shell. (This should not be confused with comic caricature.) Again, bad actors represent emotion. Good actors know how to incorporate Stanislavski’s Psycho-Physical technique, use both Elements, and recreate authentic characters using emotion and gesture.

A Note about Character

In Chapter 4 you will begin working intensively with character. The character design is a shell that must be informed by many elements including: education, culture, upbringing, personality, age, gender and more. Actors call this the mask. More importantly, remember that the emotional state is filtered through this shell (mask) of character. Therefore, how a character will react in a given situation is determined by their personal traits and emotions. For example, if a character is frightened, it will be expressed differently if the character is:

- A seventeenth-century French Countess who may have “learned emotions” and will not reveal anything that is not acceptable. Even her gestures are prescribed.

- A twentieth-century immigrant in Miami.

- A twenty-first-century teenager who tries to look “cool” and be aloof because she is afraid to show any real feelings.

Building a Character: Applying the Physical Process

Grimmy by Mike Peters

You now know how to access an authentic physicality that is connected to your emotions. Now, apply it to a character that you are developing. Whether the character is a princess, a teapot, or even Ophelia:

- Find the moment you want to express

- Use your acting technique to feel the corresponding emotion

- Apply that emotion to your body

- Transpose the Psycho-Physical knowledge to the character.

For example, an actress is studying Ophelia. She knows that Ophelia is consumed by the deaths of her father and brother, Polonius and Laertes. However, the actress has never experienced death of this magnitude. In one particular scene Ophelia is throwing imaginary flowers on her father’s grave. How does the actress emotionally connect to Ophelia doing this action? Instead of playing the amateur idea of Ophelia as a crazy young girl (running around wide-eyed), the actress looks at each moment in the play and identifies what Ophelia is feeling. In this specific moment, the actress discovers that Ophelia is sad as she remembers her father. She then explores how this specific emotion moves through her body and finds her movement to be languid and deliberate because she is reflecting on this loss. Thus, she throws the flowers slowly and deliberately onto the grave.

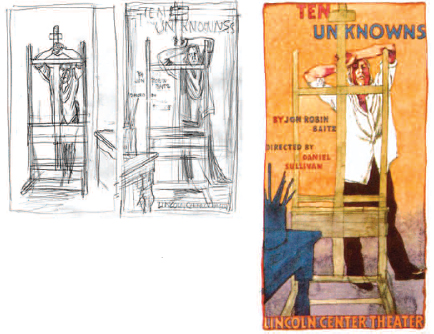

Whether your character is a chipmunk, a boy, or Buzz Lightyear, the emotions and physical manifestation of those emotions through the character’s body must be true to capture the audience’s attention. James McMullen, visual artist, grappled with just these challenges as he was developing the poster art for a new play, Ten Unknowns by Jon Robin Baitz. Using himself as the model to get to the emotion was not satisfying. He could not capture the essence of the play and character he intuitively knew he wanted.

To show how a visual artist moves beyond cliché, we only need to look at an excerpt from McMullan’s biographical blog, The Road to “Ten Unknowns,” where he outlined his creative process. Unsatisfied with crude models and general conceptions, he went straight to the actor, whose presence exploded his imagination.

I took the easel over to the theater and showed Sutherland my sketch. He said that he understood my idea and would give me a couple of variations. His variations were so full of a great actor’s physical imagination and sense of what his face and body could project that I knew, watching his changes through my camera’s viewfinder, that he was giving me the basis for a whole new kind of image. In place of the somewhat generalized melancholy of the figure in my sketch he was giving me a specific man, a heroic figure saddened by circumstance.

Sketches and Final Publicity Poster of Ten Unknowns by James McMullen

Exploring Scene Work

Metamorphosis, Photo Courtesy of Florida Studio Theatre

Catch by Chris Perry

Now that we have explored how to create emotion and gesture in a character, we will begin to place that character in a scene. The essential elements of a scene in acting are as follows: Objectives, Intentions, and Tactics.

- The Objective/Goal is what the character ultimately wants.

- The Intentions are the different ways the character tries to achieve the objective.

- The Tactics are the active choices the character uses in concert with the intentions.

We only need to look at life around us to understand scene work. As Shakespeare said, “All the world’s a stage.” Every day we live in dialogue and action. For example, suppose two sisters, Ashley and Christi, had an argument in their bedroom. Ashley storms out of the room while Christi remains sitting on the bed. Now, Ashley wants to end the argument and heal the relationship with her sister. That is her Objective. Ashley tentatively walks back into the room approaching Christi. Ashley’s Intention is to make up. Her Tactics are the ways she attempts make up. Her first tactic is to stand at the door and look longingly at her sister, hoping for a response. Her second tactic will be to gently cross to her sister and put a hand on her shoulder. Finally, her third is to give Christi a hug and ask, “Will you forgive me?” Ashley has used physical action and language in concert with her intention, to make up. And if Christi turns around and hugs her, we’ve reached a resolution.

Similarly, we can find specific examples of these elements in scenes from animation. In Up, Carl’s objective is to have control of his life and keep the memories of his wife intact. His Intention is to stay in his home, but when it is threatened the Tactic he uses to achieve his objective is to build a balloon.

The Actor Notebook for the scene with Ashley and Christi would read as follows:

Objective/Goal |

To heal relationship |

Intentions |

To make up |

Tactics |

Entreat; move closer; ask |

Actions |

Enter the room; touch sister’s shoulder; hug her sister |

Keep in mind that the tactics you choose are a reflection of the character. For instance, the tactics in the previous scene change if:

- Ashley is a confident, headstrong 19-year-old girl

- Ashley is a quiet, shy, and needy person.

The use of these essential elements gives your scene purpose and heightens the conflict. Occasionally, characters are in accord and struggle for the same goal, just as when Woody and the toys band together to save Buzz. On the other hand, when the Queen seduced Snow White into eating the poisoned apple, each character was struggling for something different and were clearly at odds. Every film, play, or animated short uses scenes just like this to tell a story, and thereby builds the conflict to reach a dynamic conclusion—the resolution.

Developing Intentions and Objectives in the Dialogue and Action

The dialogue of the characters must be imbued with the character’s Objectives and Intentions. As the great acting teacher Sonia Moore said, “The words are like toy boats on the water.” Think of every important moment in your life. Did the words ever convey the depth of your feelings? Think of the final goodbye you said to a friend or your first break up. Underneath the words are the emotional currents— the intentions, needs, goals, and desires, as expressed through the silent actions of the characters. One of the delights of the animated short is the minimal use of language. Yet, while the dialogue of a scene is usually simple, it is important to remember that the words only become powerful when they are forged with authentic emotions.

The objective, intentions, and tactics give the language its meaning and context. To learn about how an intention clarifies the language, let’s look at this sample scene with the assigned characters of A and B. You can view this work on the companion website titled Acting: Exploring the Human Condition, but first, read the scene without any inflection.

A. Hi.

B. Hi.

A. Are you okay?

B. Yeah.

A. Really?

B. Yeah.

A. Well, I’ll call you later.

B. Bye.

A. Bye.

At first glance this is a “nonsense” scene. It doesn’t really make sense, yet it feels slightly familiar because of the usage of common conversational words such as “Hi” and “Bye.” However, we don’t have any context for the scene so we don’t really know what the characters are talking about.

Impose an objective/goal on the scene to create meaning. Let’s say that Partner A’s objective is to make up with Partner B. Partner A is in love with Partner B. They had a fight. Partner A wants to make up and Partner B does too. Now, using what you learned about emotional recall or empathy read the scene out loud or with a partner.

Objective #1: To make up

Result: You can probably feel how emotionally connected the two characters are. We have all felt this. The two characters are in agreement and a resolution is reached.

Write Down Your Result:

Read the scene again and change the objectives.

- Partner A will choose to make up.

- Partner B will choose to reject.

Notice how the change in Partner B’s objective will affect the whole tenor of the script. Let’s call this scene “The Break-Up.”

Objective #2: Partner A’s objective is to make up. Partner B’s objective is to reject the offer.

Result: You will hear a completely different reading of the same scene as the objectives and intentions infuse the text with the emotional truth of the relationships. (See website.)

Write Down Your Result:

Improvisation

Mark Shira and his character from A Great Big Robot from Outer Space Ate My Homework

I can’t stress enough how acting out the scenes and filming myself on a web cam helped … it is so helpful in getting both the broad strokes as well as subtleties of performance.

—Mark Shira

The creation of something new is not accomplished by the intellect but by the play instinct.

—Carl Jung

Improvisation is unscripted, uninhibited play to discover something “new.” When actors need to find the reality of a scene, explore a character’s motivation, work out an ending, or even when they are stuck, they rely on Improvisation. Improvising a scene helps you get at its heart, for it can move you beyond the current limits of your imagination into new territory. Also, by freeing themselves from restrictions in the script and playing with the intentions and actions, the actor will discover unique gestures and movement choices that are particular to their character. Steve Smith, Director of the Big Apple Circus, author and lecturer says, “I use improvisation all the time. It gives adults permission to play; to get into the sandbox and discover and uncover the six-year-old inside of them—the innocence and naiveté that is the fountainhead of creativity. It is the truth.”

- When Improvising, remember to use your Objectives, Intentions, and Actions.

- Let yourself be unedited as you explore the story. Kick. Stomp the floor. Giggle too loud. Cry. Experience rage. You can only discover something new if you move past your limits.

- Remember that self-consciousness is antithetical to the creative process. If you get embarrassed (like Mark Shira), stop for a moment and record that process as an emotional recall memory in your Actor Notebook.

The Iconic Moment

Study of Degas’ Absinthe by Gary Schumer

Fantasia Taurina by Alejandra Pérez Gonzalez

The Iconic Moments are the important storytelling images in the scene. They are emotionally heightened because they are at once natural and familiar to the audience. They are moments that lift the audience out of the ordinary and say, “Life is important. Each moment is important. Look.” We participate in these moments every day of our lives. We only have to look around us. It is:

- The mother brushing her child’s hair

- A young son glancing back at his father before he leaves home for the first time

- Lovers parting and couples waving hello

- The greeting of long-lost brothers

- A mother carrying her dead child in war

- The teen behind the wheel of his first car.

We also see Iconic Moments in film, animation, and art. The opening moments of Up when Carl is looking through his photo albums is a powerful example because he is viewing the iconic moments of his life. Other familiar images include:

- A woman alone at a table in Degas’ Absinthe

- Rafiki holding up a newborn babe

- Bambi screaming for his mother

- Shrek and Donkey sitting under the moon

- Rodin’s sculpture The Thinker.

The Iconic Moments in the following scene can be viewed on the website, titled Acting: Exploring the Human Condition. The actors have improvised the scene that we called “The Break-Up.” Look closely at the scene and find their iconic moments. We have chosen seven. They are as follows:

1. The Anticipation

2. Seeking Comfort

3. The Look

4. The Rejection

5. The Reach (Entreaty)

6. The Crisis

7. The Disconnect (Resolution) with actors Brooke Wagstaff and Adam Ratner

Choosing the Iconic Moments is important to your story because:

- You identify what is necessary and important to the scene

- You condense the story to a feasible time period

- You identify the must-have images for the audience.

Improvise your scene and choose your Iconic Moments. When you complete your scene concept, improvise it fully and freely many times over. Remember:

- Use Objectives/Goals, Tactics, and Actions that are forged with the emotional reality of the scene

- The scene will most likely be long and formless

- Step back and look at the scene as an observer

- Identify the iconic moments: the important storytelling images.

Soon you will find the shape of your animated short and be able to move it from a generic, free-form story to the artfulness of a universal tale.

The Kite by Gwynne Olson-Wheeler

Acting is truth. It calls upon the artist to create the specific emotions of a character in the moment that are honest and true. Whether your character is a penguin, a rat, a tomato, or a Prince, they are imbued with anima—the breath of life of the human condition. Through the study of acting, the animator can access important tools to breathe a vital emotional and physical dimension into their characters.

First, by employing the Stanislavski technique of Psycho-Physical Action we learned that:

- Images create emotion

- The physical body—its movement and gesture—are a reflection of one’s inner feelings and emotion.

Moreover, in order to build an authentic character we must use the acting technique to discover:

- How a character truly feels moment to moment

- How a character moves moment to moment.

Thus, we come to the realization that both the mind and body must be employed to make a character come alive. And remember, a cliché gesture does not really express the character’s feelings and does not generate empathy from the audience.

Second, the essential elements for Scenes are as follows:

- Objectives/Goals

- Intentions

- Tactics/Actions

- Resolution.

The characters must want something with their heart and soul. They then work to get it by using their tactics until there is a resolution.

Finally, Improvisation will help you get on your feet, think outside of the box, and discover new ways that a character might behave. And, as a finishing touch, the Iconic Moments will shape the piece so that it is accessible and familiar to the audience.

Acting is truth. It is the exploration of the human condition in all its authentic joys and sorrows. Your characters will become vivid and unforgettable when infused with this concept at every given moment in your script. By learning the art of acting, your characters will be able to better communicate to us, the audience, and the more we will feel what we are supposed to feel at any given moment in the film.

- Capture “true” emotion that is authentic and specific to the moment.

- Use the Psycho-Physical technique.

- Psychological Process: Images in the mind create emotion. Use Emotional Recall and Empathy to remember a personal experience or find an emotional connection to others by asking: “What if ...”

- Physical Gestures inform the audience of the character’s emotional state.

- Avoid Cliché: generalized emotion that is not specific to the moment robs your characters of emotional truth.

- Mask/Shell: decisions regarding culture, upbringing, or personality that will determine how much of a character’s emotional core is revealed.

- Scene work involves three essential elements: Objectives, Intentions, and Tactics.

- Emotion infuses gesture, which infuses your Intentions and Tactics.

- Dialogue must be imbued with the character’s Objectives and Intentions.

- Improvisation is unscripted, uninhibited play to discover something “new.”

- Iconic Moments are the important story telling images in the scene.

- Acting is truth: the portrayal of a character that is true to the depth of the emotional reality they are trying to express.

Recommended Reading

- Ed Hooks, Acting for Animators, Revised Edition: A Complete Guide to Performance in Animation

- Keith Johnstone, Impro for Storytellers

- Charles McGaw, Acting is Believing: A Basic Method

- Sonia Moore, Training an Actor: The Stanislavski System in Class

- Viola Spolin, Improvisation for the Theatre

- Constantin Stanislavski, An Actor Prepares

The Importance of Play: An Interview with Jack Canfora, Playwright

“Play” is essential in idea and story development. It is never too soon to begin to improv your initial script, talk out your story, generate options, try things on and throw things out—allow for happy accidents to occur. In the interview below, Jack Canfora shares some of his ideas about the importance of play.

Jack Canfora is a playwright whose award-winning and critically acclaimed plays have been read and performed throughout the United States and England since 2001. Place Setting was named one of the best plays of 2007 by the New Jersey Star-Ledger. Poetic License recently finished an acclaimed run Off-Broadway at 59E59 Theaters. Jericho was named a winner of the 2010 National New Play Network. In addition to his plays his comedy writing has been seen in Greenwich Village and on the main stage of the world famous comedy club “Caroline’s.”

Q: What role does “play” have in the development of your ideas?

Jack: When you’re playing, if you’re doing it well, you’re hopefully open to things. Ideas that leap into your head, and actions and words from other people. Play is our way of understanding ourselves and the world, which is of course why children do it so often and are so good at it. It’s our point of entry to understanding the world and ourselves in the world. So how could play not be the central factor in developing ideas?

Q: When should “play” start? When does it begin with you?

Jack: I think it is the start. I was trained in improvisational acting, and a lot of its tenets are excellent guides for creative endeavors in general. There’s a rule in improv, for example, that you can’t say “no” while you’re doing a scene. That’s not to say you can never abandon an idea that isn’t playing out, but you have to follow each impulse, without reservation and judgment, until it’s been given a chance to grow and assert itself. Self-consciousness has no place in the creative act—it has a vital role, of course, in redrafting and editing, which are essential components of the finished product, but in the moment of creating, you need to be open to anything and everything as long as it feels natural and fun. Which is kind of the heart of “playing.”

Q: When you are building a narrative, how does play help in the investigation of that story?

Jack: It’s actually how I discover the narrative. For me, I think it’s essential to be incredibly kind to yourself and non-judgmental when you’re writing.

Don’t second guess. There’ll be plenty of time for that later, when you’re editing, when I would argue you need to be nothing short of ruthless with yourself. But when building the narrative, discovering what shape it wants to take, what its textures are, that’s hard to do unless you’re committed to the idea of playing around it with it.

Playing is another way of saying being open to possibilities, and that’s the only I way I can find out what I’m writing about.

Q: What is the role of an “accident” in your play?

Jack: Huge. There’s a sharp difference between creating and editing; the two together equal writing, but they’re in many ways antithetical on their own. Accidents are what you hope for; there’s no other way to discover what’s interesting and memorable without it in my experience. The crafting/editing is essential, but that’s later. It’s important not to let that contaminate the fertile period which is the creating part. You (hopefully) are always open for bringing creativity into all you do, but it’s important to keep the self-conscious, self-editing process out while you’re creating. Because then you are prone not to make mistakes, which is the same as saying you’re prone to staying predictable and uninteresting.

Q: Anything else you would like to say?

Jack: Be a magpie. Take as much as you can in from everywhere and everything. And don’t be afraid to cross-pollinate ideas/genres/techniques.

Illustration by Karen Sullivan, Ringling College of Art and Design