Finding Ideas

Eureka!, by Parrish Ley, Sheridan College

For every project, whether it is a 15-second exercise or a feature film, you will need a good idea. And if it is a good idea, is it good for the animated short?

Defining the Animated Short

The short film is defined as 24 minutes or fewer. In animation, commercial shorts usually run 6 to 11 minutes and are created by teams with big budgets and resources. We are defining the short as what is feasible for the individual, beginning animator. This is a running time of approximately one to three minutes, about the length of one scene in a feature film.

The story ultimately determines the size of the short. It depends on whether you are working alone or in a group, the time you have and the amount of time you are willing to spend on the project. It depends on your resources. And it depends on how much information and complexity you can handle, both conceptually and technically, and still move an audience emotionally.

Before You Start

Before you start, it is good to know a few rules of the playground.

The Rules of the Playground

Rule #1: Story is King

Story will infuse all the work that you do. As a shorts producer, you may wear all the hats of production: writer, director, concept artist, storyboard artist, modeler, rigger, animator, lighting and texturing artist, sound director and editor. What ties all these positions together is the story. Without a story, all you have is technique.

Technique and skill are crucial, but there are times when an audience (not an employer) will forgive poor technique. However, it will never forgive a poor story.

Rule #2: Keep It Simple

A good idea for a short is simple. It isn’t too complicated and it isn’t too big. It has a set up, makes a point and ends.

Remember: one theme, one conflict, two characters, two locations and only the props necessary to tell the story. If you can’t define how something in the story supports the theme, get rid of it.

What types of ideas work for the short?

- Simple, single situations

- Someone wants a bite of your food

- One conflict that intensifies

- I give him one bite. Now he wants more. I give him all but one bite—which I eat. Now he wants me … uh oh.

- A single, memorable moment

- Ed Hooks, author of Acting for Animators, calls a memorable moment an adrenaline moment.1 Something that happens to the character that is of such great emotional significance that he will remember it when he is 90. I remember the day a bull chased me for an apple.

- Slices of life

- I once shared an apple with a bull by a pond.

- Demonstrations of personality

- Let me show you what a bull looks like when he’s mad.

- Jokes

- Did you hear the one about a bull and a bee? I tried to rescue it—but it rescued me!

Fantasia Taurina by Alejandra Perez, Vancouver Film School

Of these, the hardest is a slice of life because the conflict is usually inherent. For instance, in Chelsea Bartlett’s Treasure, the conflict is that a woman lives in a junk yard. We watch her go through her day, wondering why she selects certain objects and discards others—when we discover she is making the junk yard a beautiful place.

Treasure by Chelsea Bartlett, Ringling College of Art and Design

What types of stories don’t work for the short?

- Hero’s Journeys

- Epic Tales

- Uncharted Territories or Complicated Concepts

- You will spend all your time explaining where we are or how it works.

- Little-Known Facts

- You may know that penguins use oil from a gland to make their feathers waterproof, but if your story is that a penguin is out of oil, most people won’t get it.

Rule #3: Know the Theme

Remember that stories have meaning and themes are life lessons. The theme is not the premise or the plot. For any theme, there could be many narratives that communicate it.

For the short, there should be one theme and you should be able to state it in one sentence. Keep it simple, clear and direct. It should have a viewpoint. There is little time to present an unbiased and balanced commentary.

Fantasia Taurina

Concept: Sharing is better than selfishness

Premise: A bull is angry when a young child steals its apples, but is soon in need of her help.

The theme is the one non-negotiable element of your story. Everything else is swappable—characters, locations, plots. But what you want to say, your theme, is the backbone of your story. When you’re not sure what is necessary in your film, put it against your theme.

A cliché is a concept, character, symbol or plot device that has been so overused that it has lost its originality.

Cliché Concepts:

- Love conquers all

- Technology is bad

- Nature is good.

Characters:

- Robots

- Aliens

- Mimes

- Ninjas

- Fairies

- Dragons

- Pirates

- Superheroes

- Big-breasted women with guns.

Symbols:

- Butterflies

- Open windows

- Chess boards

- Sunsets

- Gravestones.

Plots:

- It was all a dream.

- Country mouse (or woodland animals) in the city or vice versa.

- Child’s imagination (usually with monsters or imaginary friends) takes him on an adventure.

- Little kid learns something that makes them grow up.

- A lonely kid makes a robot friend.

- A character must choose between two pathways or doorways.

In an effort to be clear, it is easy to default to cliché. If you have heard it before, stop and rethink it. If you choose to use something that is cliché, you have to find a way to make it fresh and original.

Nilah Magruder uses zombies (which are a cliché) in her animatic, Teddy, about a young girl running from them in a destroyed suburb. When a zombie girl surprises her, she drops her teddy bear, they struggle, and she pulls off the zombie’s arm. The zombie girl grabs her arm back, sits and cries. Key point: Who knew zombies had feelings? The girl offers her the bear, and in turn, the zombie girl offers her the arm—which although dismembered is still alive and gives the girl a hug. The story does not work because of the zombies—it works because it is about empathy and understanding someone different.

Preproduction Animatic: Teddy by Nilah Magruder, Ringling College of Art and Design

When you are working with a cliché, go to the theme, the life lesson, to make it fresh.

Rule # 5: Create a Memorable Character

Shrek, Hogarth, Nemo, Woody, Howl, Rango, Hiccup—we remember them all. Why?

A memorable character is ordinary enough for the audience to relate to with flaws that make them unique and accessible.

There is “something” (extraordinary) about their design and personality that makes us empathize with their plight.

The test of a good character is that he cannot be replaced with someone or something else. Replaceable characters are flat. You can swap them out (a boy for a girl for a squirrel for a squid) and it doesn’t affect the story. But when you find the right character, it is difficult to remove them from the story because it is their story. And through their story, they teach us something.

Poor Bogo by Thelvin Cabezas, Ringling College of Art and Design

Rule #6: Emotion Drives Action

A story is defined by the character. More specifically, it is defined by how the character reacts to a situation.

Action never just happens. Action is the result of thought and emotion.

Too often the beginning storyteller will create the events—what the character does, the action he takes— instead of looking at the emotional changes in the character as he meets the rising conflicts. If story is king, emotion is ruler of the universe. It is how the character feels and then how he reacts to how he feels that retains your audience.

“My Tomato!” Gopher Broke crow, Illustration by Sean McNally, Blur Studios

Rule #7: Show Don’t Tell

This is the golden rule of film. “Telling” means the use of exposition or description without engaging the emotional or sensory experiences of the character or the audience. Usually this involves bad dialogue that hits you over the head, explanatory narration or the use of signs (not symbols and semiotics here, but actual written signs like “This Way to the Death Chamber”).

Showing means to make clearly evident, by the appearance, behavior, action or reaction, the character’s emotional experience too. It is the epitome of the adage, “Actions speak louder than words.” Through gesture or props, showing creates a visual that communicates the theme, feeling or content. Showing involves communicating the emotional and visceral experience of the content.

In the animated short, where there is little or no dialogue, the question of what we see becomes critical.

You need to consider, from the initial idea, what we are going to see. It is never too soon to begin to make your piece visual. It is often the visual that sells the idea. And in animation, it is not only what a character does, but how he does it that makes it poignant or entertaining.

Rule #8: Create Conflict

This may seem obvious given our base definition of story. However, an initial pitch will often include wonderful characters moving through events, but it is all exposition. There is no conflict and consequently, there is no ending because there is nothing to resolve.

In Respire, Mon Ami there is a lonely boy, but this conflict is resolved in the inciting moment when he finds a severed head at a guillotine. From that moment until the boy believes his friend has “died” we have nothing but exposition as we build the relationship. If the head did not expire, we would never have a conflict.

Respire, Mon Ami by Chris Nabholz, Ringling College of Art and Design

Conflict = drama.

Remember that there are three, and only three, kinds of conflict:

- Character vs. Character: Characters need opposing goals. If both characters want the same thing, there is either: a) no conflict or b) you can tell the story with one character.

- Character vs. Environment: The character struggles against the environment. “Environment” can be an interior, or exterior.

- Character vs. Self: This is the hardest to animate because the conflict is internal. Eureka! does a good job of making an internal conflict (the need to think of an idea, to solve a problem) externalized in the light bulb above the professor’s head. When the normal process or pathway to creativity is broken, the professor flails wildly in frustration, unaware the source of his ideas is still there. Order is restored only when a new pathway found.

When discussing conflict, it is also necessary to discuss what conflict is not. Conflict is not a sword fight, war, car chase or competition. These are the results of the character in opposition.

Rule #9: Know Your Ending

You can’t really tell your story until you know the ending. Sometimes the idea you find will be the ending—the punch line or the payoff. Endings must transform the character, the audience, or both.

Rule #10: Entertain Your Audience

Audiences are entertained when they are visually, intellectually and emotionally engaged.

When audiences watch a film, they are looking for an experience. They will suspend disbelief and travel with you as long as you maintain the rules of your world and keep the story truthful and the characters believable.

The best shorts are the ones that have some adventure, sorrow and laughter. They are the ones that hold a few surprises and the ones you continue to think about after you see them. How will your audience feel, and what will they remember from yours?

Rule #11: Make Me Laugh

Most people, when they think of humor and animation, think of Tex Avery, Chuck Jones, sight gags and visual puns. Humor can also be parody, satire or pathos.

The best humor in a short is the type that grows out of the situation, reinforces the conflict or emotion of the characters or subtly reveals more about the character. It is sometimes funny, sometimes nervous, and sometimes empathetic.

In Respire, Mon Ami, the young boy tries to revive his friend with mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. The humor comes from three sources: 1) from the fact the head is dead and cannot be revived, 2) from the gross factor of the act itself, and 3) from the breath of the boy escaping out the neck to rustle the leaves on the ground.

Respire, Mon Ami by Chris Nabholz, Ringling College of Art and Design

Humor can come from empathy and failure as we watch a character attempt to fly a kite.

Kite by Glynn Olson-Wheeler, Ringling College of Art and Design

It can come from the burp of a Cap who has drunk the magic potion. Burps, farts and body jokes are popular forms of humor. We can point to numerous feature films that include them. However, if you analyze these carefully, these kinds of jokes are usually secondary humor. They are not the primary content that drives the scene. If they are, they are related to the situation in which they occur and what is poignant is not the burp or fart, but the reaction to it. Note the reaction of the green Cap’s friends. And note the result of him drinking the potion.

Caps, directed by Moritz Mayerhofer and Jan Locher, Filmakademie Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany

Rule #12: Answer the Question: Why Animation?

How are you going to employ the unique characteristics of animation? When someone asks you why you are using animation to create a film there needs to be a good reason. There needs to be something in the design and the storyline of your piece that requires animation.

This could be exaggeration, caricature, or process. Sometimes animation is a better medium to use because of your proposed content. Using anthropomorphic animals allows us to look at our human characteristics, our failings and shortcomings that otherwise would be difficult to watch.

Why? Much of this has to do with time and cost. If it is a piece that you could produce easier, cheaper, faster and better in live action, why are you doing it with animated media?

The Cardinal Rule: Do Something You Like

If you don’t like what you are doing, it will show in the work and no one else will like it. Choose something that you like, that can sustain you for the months it will take to produce it.

Finally, for every rule, there is an exception to the rule. Learn the rules, and then break them.

Getting Ideas

Now that we know the rules of the playground, where do good ideas come from?

Kevin Andrus, Ringling College of Art and Design

The Ideal

The most linear path for getting and developing ideas comes from first knowing your theme. If you know what your piece is about, it is easy to determine early on which elements you need to tell your story: the situation that will best convey your message; the characters that will be in conflict; your genre; time period; lighting, costuming; etc.

This is the most straightforward approach because your theme is what drives everything else. It is the sounding board against which you place your possibilities and if your possibilities do not support your concept, you eliminate them.

Chris Perry’s piece Catch is an example of a piece that started with a concept:

Catch by Chris Perry, University of Massachusetts at Amherst

Catch really grew out of a statistic I heard a while back. I think it was something like “50 percent of all middle school girls are on a diet.” This came up in the context of a conversation about how advertising succeeds at making people, especially girls, feel unhappy with themselves. At the time, my wife and I were expecting a girl and I pictured her wandering through fields of giant billboards which were coming to life, reaching down and trying to snare her. But she was trying to chase this ball as it rolled underneath the billboards, and she was so small they couldn’t grab her.

The simplicity of Catch is deliberate: I wanted the advertisement image to stand out as striking and unusual because such images don’t stand out in our everyday existence (and they should). The models used in advertisements represent the smallest sample of what women’s bodies really look like, and the money spent to craft the perfect image defies the final result’s impromptu, casual appearance.

The story was basically intact from the storyboard phase on, though I did have her try to throw the ball up at the tree while lying on her back (something I used to do). But that was hard to stage clearly so I switched it for the throwing game. The little gag about the sagging breast was an exception: it came up between storyboarding and animation when I was acting out that key moment of the film and trying to figure out how to visually show that this new breast wasn’t doing anything for her. It was also always part of the film that gaining the adult-like chest required the removal of the ball game (putting those two desires completely against each other, so she couldn’t have both).

The primary theme of Catch to me is about being yourself. If the film works, it works because when she is standing still with a big chest and doing nothing, it is a complete and absurd contrast to her activeness and creativity at the start of the film. “Is this what being like that person in the picture is like? How dull!”

The Real

More often than not, we start with a seed or inspiration from somewhere or something else. It could be a character design we have drawn, a location we have seen or a situation we have experienced. All of these are harder, but more visual places to start. It just takes a little more work to find the essence of your piece.

When starting with a character, you will need to figure out who that character is and then fabricate a situation that will put him in conflict.

When starting with a location, you need to discover why you are attracted to it and what potential it has for story. Populate it with characters. Who would be in that space? What do they do? What would disrupt what they usually do? If the location is generally familiar, what has changed or what is out of place that creates implications or questions in your audience’s mind? What is the atmosphere of the place and what does that mean?

In Triplets of Belleville, three great cities—New York, Montreal, and Paris—were combined to create a place that felt familiar and communicated wealth, materialism and scale, in contrast to the poverty of Mme. Souza and her dog.

Evgeni Tomov, art director on Belleville, explains:

The direction Sylvain Chomet gave me, he told me it should be a very interesting city, where there is an abundance cult for consumerism and food is a typical thing. And that’s why you see so many obese people—and the characters in Belleville—you can see it for yourself—they represent this over consumerism.2

The Triplets of Belleville, directed by Sylvain Chomet

Sometimes, the location can tell the whole story. Ray Bradbury wrote the short story, “There Will Come Soft Rains,” that follows the functions of a “smart house” long after the residents have died. Through the house itself, the lives of the people who lived there are revealed and the purpose of the house to protect them is jeopardized.3 There are a lot of mechanical devices and effects to watch that could make this good for animation.

When starting with a situation, you have to create conflict. Two people at a table having a conversation is a situation. Two people at a table fighting over the check is a conflict. To make this stronger, there has to be something at stake. What does it mean to each of these characters if they do not pay the bill? What could make this better for animation than live action? What are the extremes that the characters go to in order to win the conflict? What other situations are similar that could tell the story better?

When You Have Nothing …

1. Start with Yourself.

There is no better source of story than you: likes, dislikes, what you know. Story is driven by emotion, so start with that. What makes you happy, mad, sad, frustrated, surprised, or hopeful? What makes you laugh? What is the one thing you would like to change about the world? What’s your perfect day? What is your biggest ambition? What is something you’ve always wanted to do but haven’t? Be your own character.

2. Ask Why?

Look at the assumptions in your life. Why are things the way they are? Turn them over. Look at them from another viewpoint. Monsters have hidden under children’s beds and in children’s closets forever. Everyone knows they are there to scare children. But no one until Pixar, with Monsters, Inc., asked why. What’s in it for the monster? It’s their job. But what is the payoff for doing this? Ah … it is their source of power. Brilliant.

3. Go into the World and Watch.

Observation is one of an animator’s greatest tools. The world is full of people in conflict—from the simple choice of paper or plastic, to climbing Mount Everest. And people do the craziest things for the silliest reasons. The human race is full of emotions, logic, faults, quirks, fallacies which all make great fodder for animation. They have great movements, expressions, walks and weight shifts. Sometimes something as simple as an interesting walk can reveal a character and launch a story.

Educator and Animator Jamie DeRuyter tells this story:

I was in a bar. The bartender is telling a story to a couple of guys sitting at the bar. He begins to wash some glasses while he’s yappin’. He picks up two glasses, plunges them into the swirling washer in the sink, splashes them into the rinse sink #1, then rinse sink #2 (the one with the sanitizer that is required by law), then sets them down to dry. I’m not sure how many people have tended bar or sat at a lot of bars, but that is a standard bar glass wash: scrub, rinse, sanitize, stack.

So, he’s getting further along in his story, washing glasses (lots of them), when I notice he skipped the second rinse (sanitize) on one set of glasses. He’s really getting into telling this story. The dudes he’s telling it to are totally on the edge of their seats waiting to hear how this comes out. They can’t see the wash sinks and what he’s doing under the bar in front of them. As the bartender continues to wash and talk, he skips the sanitize a couple more times. Then, on one set of glasses he skipped both rinses. Hahahaha, the story is really getting funny now. All three of the guys are laughing out loud. Then he grabs four glasses, gestures with them once or twice as he lays down the climax of his tale, waves them past all three sinks … Then the guys order another round for the bar and he fills the glasses … those glasses … my glass has lipstick. I’m sure my reactions were priceless. Uh, bartender, check please?

4. Create Some Innocent Trouble.

When we are in negotiation, we are emotionally involved and rarely have the opportunity to observe the reactions and emotions of ourselves and other people. At the grocery store, when the cashier asks if you want paper or plastic, reply “Both.” And then be specific about which items you want in paper and which you want in plastic. Watch how they react. See if they will do it. Be careful not to push too far. You are doing a study, not getting in trouble.4

My student, Ryan, went to McDonalds. He ordered a Big Mac but asked that everything be wrapped in a separate piece of paper or put in a separate container—the beef patty, special sauce, lettuce, cheese, pickles, onions and sesame seed bun. They did it. Then he sat at the table closest to the cashier, put it back together, and ate it. The reactions were perfect for animation.

5. Read the News.

The news is full of stories. Sometimes you just get handed one that would make a good film.

Look at this headline: “Thief Makes Getaway on Pedal Go-cart.” Apparently a thief was caught while loading his car with stolen merchandise. Taking off on foot, he lost a shoe and sock in the mud. Thinking it would be a faster getaway, he jumped into a pedal go-cart that he later abandoned for faster transportation—a bicycle. Dumping the bicycle he ran through a cemetery where the police were able to track his one-shoed footprints to where he was hiding behind a tombstone.5

The only thing that would make this better is if he had stolen a pair of shoes.

6. Look at Art.

What attracts you? Why? Is it color, composition, light, subject matter? Cezanne told story through light. Brancusi created flight out of stone. Each piece of art tells a story. If you lay that story over time, what is it?

Meghan Stockham’s animation, Beware of Monster, was inspired by a piece of art that illustrated a little girl blowing bubbles on a dock. Below her in the water was a creature. Meghan asked, what if the monster really wanted the bubbles? The bubbles were eventually swapped out for flowers.

7. Make an Adaptation of Another Story.

You don’t want to illustrate another story, but use it as inspiration or reference. What is the essence or concept of the story? What are parallel situations and conflicts? How can you translate it into your own form? What if you tell the same story from another viewpoint? Tell “Little Red Riding Hood” as the wolf or the basket or the path. Don’t be afraid to steal the essence of another story. Remember that there are a limited number of stories recreated in new forms. Without “Cinderella” we wouldn’t have Pretty Woman. The advantage of revising a known story is that instead of spending time telling a new story, you can reinvent it or up the visuals to make us see it in a new way.

8. Parody a Current Story or Event.

A parody is a humorous imitation that makes fun of or mocks someone, or something. It plays in the world of irony, sarcasm and sometimes ridicule. Politics, current events, songs and popular culture are frequently the subject of parody and satire. Think of South Park, Family Guy or old Warner cartoons like Bugs Bunny.

9. Create a Competition, Play with Status.

In conflict, we talked about characters that have opposing goals. Sometimes, in stories of competition, characters have the same goal and are pitted against each other. These stories often use status relationships (who has power) and status often transfers from character to character as they meet with conflict. In Kung Fu Panda, Po competes with Master Shifu for a dumpling. Dueling chopsticks and kung fu moves bring Po to the level of kung fu master—and he can eat.

10. Combine Unlike Things Together.

What if you had enough balloons to lift a house? What if food rained from the sky? What if fish had hands? What if’s and unusual combinations can result in unique ideas. In Toy Story, think of all Sid’s combined toys. They each have a weird little story. Or in Coraline, think about the transformation of the “other mother” into a spider.

“There’s no use trying,” [Alice] said. “One can’t believe impossible things.”

“I daresay you haven’t much practice,” said the Queen. “When I was your age, I always did it for half-an-hour a day. Why, sometimes I’ve believed as many as six impossible things before breakfast.”

—Lewis Carroll, Through the Looking Glass

Getting ideas takes practice. Can you get six ideas today?

Pursuing Ideas

Trust yourself. If it moves you, give it a chance. Don’t hold back. Monty Python had a great working principle. They went with any idea one of them had, even if others didn’t like it. They gave anything a chance to live on. Sometimes this resulted in a failed skit, but other times the results were completely unexpected and fantastic. If they had held back during early conceptualizing, they wouldn’t have reached the unusual peaks they reached.

—Larry Weinberg6

In the short, you are searching for the best way to tell your story. Planning your animation takes as much time, rigor and engagement (fun and frustration) as it will take to animate it. Try to defer judgment until you play out your ideas.

Because we are people, and stories are about people, we draw from our own experiences, dreams, and observations. Frequently our first ideas have characters that are people and situations that initially are better for live action than animation. You have to play with these ideas and find exaggeration, metaphor and analogies that push the idea outside the boundaries of live action or communicate what you want to say in another form.

There are some tools we use to do this: Research, Brainstorming, Condensation and Displacement. These are not isolated tools, but you move back and forth between them as you develop a story.

Research

There are three forms of research that you can employ to learn more about the content you need.

1. Factual Research.

Once you have your characters, conflict and location, there will be a lot of things that you don’t know. What do you know about medieval dragons or being lost at sea? This kind of research includes the mechanics of how something works, the architecture, costuming or products of a particular era (what did a Coke bottle look like in 1962?); cultural influences on your character or even what film, photography, advertising and art look like in the time period of your film. When Brad Bird made Iron Giant he filmed it in Cinemascope because that was the film ratio that was used in the 1950s, the time period of the story. He believed that using a film ratio from the time period of the story helped support the story itself.7 Factual research can be an incredibly inspiring tool that can lead you to all types of potential for conflict and change. Change may lead to more research. Understanding the parameters of your content is important because in your audience, someone knows your topic better than you. And if you pass this off as “just animation” you will break the suspension of disbelief for someone in your audience.

Ritterschlag directed by Sven Martin, Filmakademie Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany

2. Observational Research.

We have already covered the fact that observation is one of an animator’s greatest tools. You can learn a lot by watching. If you need to animate a lizard, get one. Time the pacing of its movements. Record how it shifts weight when it walks, climbs, or twitches its tail. What else can you learn about it? How does it eat, sleep and socialize? Observation can help you discover the essence of your character, location or situation.

3. Experiential Research.

This type of research is the most fun because you get to do things. When Pixar was making Finding Nemo, John Lasseter had the animators go scuba diving. He thought they could not accurately animate an underwater movie unless they had experienced it. It is an entirely different thing to feel the resistance of the water, see the diffusion of the light, and swim with fish than to read about them or look at pictures.8

Experiential research is also where you act out what your character has to do. It is not enough to think about or observe an action. You need to get on your feet and do that action. Feel the force, weight and pacing of the movement. Sometimes you will have to animate a character or creature who moves very differently than you do, that has a very different weight, force and attitude than yours. A great exercise is to follow someone with a very different build and attitude from your own. Try to walk in their shoes— literally. Mirror their gait, the tilt of their head, the angle of their shoulders, the turn of their feet, the swing of their arms, and the angle of their hips. You will learn a lot about them from how they move as opposed to how you move.

Flight of Fancy by Casey Robin, Video Reference and Drawn Frame from Animatic

Brainstorming

Most creativity texts will direct you to be uninhibited when you brainstorm. Anything goes. Play “what if” extensively. To some degree, this is true. But when developing story, you may get there faster if you work within parameters:

- Define the time period and genre of your piece. Is it a horror, mystery, comedy, action-adventure, Western, sci-fi, film noir, etc. and when does it take place?

- Cast and recast your characters until you find the right personality.

- List the attributes of your character, what they do and where they do it. Attributes are all of the details you need to include your visuals. Look at this sentence: “The owner chased his dog through the crowded street.” Clear enough. Until you draw it. What does the owner look like? How does exactly does he “chase”? Does he run, hobble, limp? What is the breed of dog? And who or what is around the street? Is it a parade? Marketplace? Wall Street traders?

- Finding metaphors. A metaphor is something that takes the place of something else. A child at play becomes a monkey. A methodical engineer becomes a robot. And they become something else because that “something” is closer to the actual essence of the character than the default package (human) in which you find it.

Brainstorm and share your ideas with others. Your piece will make sense to you because you made it. That doesn’t mean it makes sense to others—and remember, stories are meant to be told to other people. Kick around your ideas. More minds make for more ideas.

Condensation

What if your idea has too many characters, events or locations? Do you automatically abandon it? No. It may be that when you understand the essence of the story, it is possible to condense armies into a single soldier, or a journey around the world into a walk around the block.

Let’s play what if and condense one of our bigger stories, Noggin. Let’s say that this was your idea but you either didn’t have, or didn’t want to work with anyone else. Could you tell this story with two characters?

First, we need to determine what Noggin is about. What is the concept of the piece?

Possible concepts that are within a standard deviation might be:

- Mutations save the species.

- Sometimes your differences are your strongest asset.

- Survival of the fittest.

Premise: Noggin, a caveman, lives in conflict with the Bellyfaces who don’t appreciate how his differences complicate their lives. Noggin’s differences are what save him.

Without the introduction, we assume that Noggin is the first man, a mutation, living with Bellyfaces who ostracize him for being different—a head on the shoulders. He scares prey because his head sticks above their hiding place, and his head smothers fire, which they worship, when he bows before it. The Bellyfaces decide his head must go. But it is storming. And when a great flood comes, Noggin is the only creature who has his head above the water.

Noggin, directed by Alex Cannon, Brigham Young University

The Bellyfaces are essentially all the same, so we could condense them into one character. Then populate the environment with symbols or images of the Bellyfaces, so your audience knows that Bellyfaces dominate the region. And we could probably do it all in and around the camp.

Noggin, directed by Alex Cannon, Brigham Young University

So we have two characters and one location. But in this piece, we still have a long traditional intro, a quadruped deer and a flood. Cut the intro. The flood, the way it is staged and handled, is OK. The deer is a problem. You have to model, rig and animate a deer for just a few seconds of movement. Maybe it could be a gopher that pops his head out of a hole. Simpler, better. The “prey” is swappable for feasibility without hurting the idea or action.

Displacement means to change or displace to another viewpoint or context of a piece while maintaining the same story. When beginning to work ideas, look at all of the characters and toys at your disposal. Try telling the story through each of them individually and see what happens.

Poor Bogo is a story about a conflict between a father and his small daughter. The father wants his daughter to go to sleep and she wants to continue telling a favorite bedtime story. Initially, this is an idea that would seem better for live action. You could caricature the players and stylize the room, and exaggerate the antics of the child and the sheer exhaustion of the father and this might suffice. But Thelvin Cabezas did a brilliant thing. He displaced the story to the object that was between the father and the child—the bedtime story.

Poor Bogo, by Thelvin Cabezas, Ringling College of Art and Design

This makes Poor Bogo more complex. The conflict is character against character. The child wants to stay awake and expand on the story of Bogo. This conflict is negotiated as the audience watches the child’s imagination and the continuing story of Bogo. We have a story within a story.

Bogo, the hero of the child’s story, pursues candy. His conflict is twofold. He is in conflict with his environment, which poses physical obstacles to the candy: treasure chests, ice cubes and falling stars. He is also in conflict with the father, who uses logic to dispel the obstacles, just before Bogo can get the candy. And when the obstacles disappear, so does the candy. This has an emotional effect on Bogo and he relies on the child to infuse his goal with situations and hope.

By displacing the conflict between the father and child to the imaginary story, the artist allows the audience an insight into the much richer world of the child. Each time the father dispels the illusion with logic, Bogo is disappointed and we, too, are afraid that the story is over.

The main characters, father and child, do not have an arc, learn or experience an adrenaline moment. However, Bogo does. Remember the time I found a treasure chest? Remember the time there was an ice cube in the desert and when candy fell from the sky? Remember that there won’t be any more adventures until another night (and remember I never got to eat my candy!). Poor Bogo.

There will be times when you have an idea but you need to make dramatic changes to make it appealing, entertaining or executable in animation. So many short ideas start in a contemporary time period and setting with characters. This is because stories are about us—and we have been repeatedly told to write (or draw) what we know. Often this results in a story that stems from personal experience but not in a form that is entertaining. Remember: one of the challenges of constructing a story is that we are trying to communicate with a mass audience. When working on your idea, you want to make sure it is the most entertaining way to reach them.

Example:

Theme: Some of us grow faster than others, but it is going to happen to everyone.

Premise: On a playground, Sarah Jenkins, a blossoming adolescent, is taunted by her slightly younger friends.

This premise has some problems:

- It has multiple human characters—Sarah and her peers.

- The location, a playground, has multiple props to model.

- The conflict—taunting—seems to require using dialogue.

- The basis for the story is blossoming adolescence or puberty. This is a time of life that is hard to talk about as you are going through it and after you’ve been through it—you never want to go there again. It includes the visual attributes of pimples, greasy hair and budding bodies. Yuck. How do you make the physicality of adolescence appealing?

However, it has a strong life lesson for both Sarah and her peers and since this is a premise you want to develop, and you’re passionate about it, the question becomes, how do we improve it?

Stories have essentials that must be kept. In this story the essentials include Sarah, something that develops, taunting and Sarah’s desire to belong. Everything else is “swappable.” Swappables are things we can “trade out” to try to find better toys with which to tell the story.

Swappables include:

- The character’s physicality. What is something more palatable and interesting that develops, transforms or mutates? What about a caterpillar, Spider-Man or a transformer?

- Genre. Right now this is a coming of age story, but what if you change the genre? What if it is a sci-fi story, an action adventure or a Western? What if Sarah is just a stranger in town that needs to learn who she really is?

- Time and place. What if the story takes place during prehistoric time and Sarah becomes Noggin, taunted by Bellyfaces because she has a head?

- Point of view. Whose story is it? Right now it is Sarah’s. Would it be a better story, or would we learn a better lesson, if it were told through the eyes of the friend?

Early Bloomer, directed by Sande Scoredos, Sony Pictures Imageworks

There are many stories that, if you look close enough, are the same story.

Sony Pictures Imageworks told this story through the eyes of a tadpole that begins its transformation just ahead of its peers. It works well because:

- It displaces a common and overused theme to something fresh and new.

- It is told from the point of view of a tadpole.

- It takes us to a new place, underwater, where we are not sure exactly what we will find.

- Tadpole metamorphosis follows a visual pattern over a relatively short time. The development involves the growth of feet and arms. Hands and feet are something we don’t mind watching develop. The feet and arms can “pop” from the body adding surprise and entertainment.

- All tadpoles look the same to us so, aside from color, all the models are the same. There is still a lot to animate but suddenly we have something feasible for the individual animator.

- Underwater is a hard place to be for an animator, but thinking carefully about style choices often make this feasible as well.

- It allows us to look at a time that was awkward for many of us with empathy and humor. It turns teenage angst into a comedy.

- It maintains the essentials of the premise while adding appeal and entertainment value.

- It works as an animation because the characters are stylized and the medium provides imaginative possibilities.

New premise: A green tadpole is taunted by her slightly smaller friends as she begins her transformation into a frog.

Theme or concept: Some of us grow faster than others, but it is going to happen to everyone.

Bottle

Another piece where swappables turn something mundane into an extraordinary film is Kirsten Lepore’s Bottle. The initial concept is pretty boring. This piece is about penpals who decide to meet. It isn’t very interesting to watch people write to each other. But Kirsten did an amazing job of incorporating swappables that make this piece an award winner. Penpals become a sandman and a snowman—polar opposites environmentally. What separates them is an ocean. And how they communicate is through a message in a bottle (using objects not words) … something that holds intrigue for us as they discover more about each other and finally decide to meet. And to meet they must venture into the ocean …

Bottle by Kirsten Lepore

Before you start looking for ideas, know the rules of the animation playground:

- Story is King

- Keep It Simple

- Know Your Concept or Theme

- Avoid Cliché

- Create a Memorable Character

- Emotion Drives Action

- Show Don’t Tell

- Create Conflict

- Know Your Ending

- Entertain Your Audience

- Make Me Laugh

- Answer the Question “Why Animation?”

- Do Something You Like

- There Are No Rules.

Getting ideas takes practice and hard work. Ideas come from:

- Everywhere

- Concepts

- Characters

- Location

- Situation

- Experience

- Questions

- Observation

- Negotiation

- Newspapers

- Art

- Other Stories

- Competition

- Combination

- Thinking Impossible Things.

Giving ideas form involves thinking through the possibilities. Tools for pursuing ideas include:

- Research

- Brainstorming

- Condensation

- Displacement

- Swappables.

Additional Resources: www.ideasfortheanimatedshort.com

- Industry Interviews: The Ideas Behind Gopher Broke: An Interview with Jeff Fowler, Blur Studios

- All the films are located on the web in one of the following three places:

- Case Studies

− The Fantastic Flying Books of Mr. Morris Lessmore: An Interview with Brandon Oldenburg and Adam Volker. Find out where the idea for this film came from.

− A Good Deed, Indeed documents a initial brainstorming session on the beginning of a film.

- Designing for a Skill Set

− Make sure to check out Robert Showalter’s interview in Designing for a Lighting Project. It has a wonderful story on how his idea developed.

- More Films

- Case Studies

Recommended Reading

- Don Hahn, Dancing Corndogs in the Night

- Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas, Too Funny for Words: Disney’s Greatest Sight Gags

- Michael Rabiger, Developing Story Ideas

- James L. Adams, Conceptual Blockbusting

- Jack Ricchiuto, Collaborative Creativity

Notes

1 Ed Hooks, Acting For Animators, Heinemann Press, Portsmouth, N.H., 2003, p. 116.

2 Sylvain Chomet, The Triplets of Belleville DVD: The Cartoon According to Director Sylvain Chomet featurette, by Michel Robin, Beatrice Bonifassi, Jean-Claude Donda and Mari-Lou Gauthier, released by Sony Pictures, 2004.

3 Ray Bradbury, The Martian Chronicles: There Will Come Soft Rains, Spectra; Grand Master edition, 1984, p. 166.

4 Katherine Tanner, Florida Studio Theatre, Acting Workshops for Animators Homework Assignment.

5 http://www.spiegel.de/international/zeitgeist/0,1518,543275,00.html

6 Angie Jones and Jamie Oliff, Thinking Animation: Bridging the Gap between 2D and CG, Course Technology PTR; 1 edition, 2006, p. 116.

7 Salon.com, Arts and Entertainment Column: Iron without Irony, August 1999. http://www.salon.com/ent/col/srag/1999/08/05/bird/index.html

8 Eric Bana, Nicholas Bird (II), Albert Brooks, and Willem Dafoe, Finding Nemo DVD, Collector’s Edition: Making Nemo, Pixar Animation Studios, released by Walt Disney Pictures, 2003.

The Ideas Behind Technological Threat: An Interview with Bill and Sue Kroyer

William “Bill” Kroyer has been an award-winning director of animation, commercials, short films, movie titles and theatrical films for over 30 years. He was one of the main animators for the CGI sequences in Tron, and worked on Disney’s The Black Cauldron. He was Senior Animation Director at Rhythm and Hues on Garfield, Scooby Doo, and Cats & Dogs. Bill is currently the head of the Digital Arts Department at the Lawrence and Kristina Dodge College of Film and Media Arts at Chapman University.

Sue Kroyer is an animator and producer who has worked in the animation industry for over 30 years. She has worked for Disney, Warner Brothers, Brad Bird, The Simpsons, Richard Williams and Bob Kurtz.

Bill and Sue Kroyer also owned their own studio, Kroyer Films, where they produced the feature film FernGully: The Last Rainforest. Their studio also produced numerous theatrical film titles such as Honey, I Shrunk the Kids and National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation. Their short film, Technological Threat, was nominated for an Academy Award.

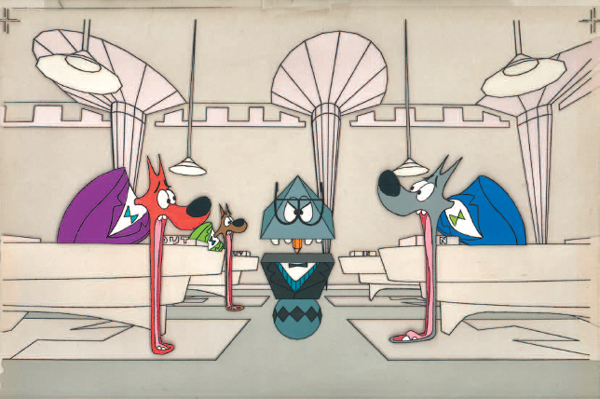

Technological Threat is a five-minute animated film made in 1988. It was the first example of early computer animation, integrated with traditional animation. It is a story about robots that are taking over humans (in this case they are dogs) in the workplace. The robots and backgrounds were a combination of drawings and computer-generated 3D models, while the dogs were drawn by hand. The film is an allegory for the threat that computer animation represented to traditional animators at the time.

Image from Technological Threat, courtesy of Bill and Sue Kroyer, all rights reserved

Q: What advice would you give to a student on how to make a short film?

Bill: Have a good idea and have something to say. An image or gag is not enough. It’s difficult to create something totally original. As long as you don’t directly copy something that has been done, it doesn’t mean you can’t be influenced. At the end of the day you want to try and make something that’s wholly your statement. If you do that it will be unique and hopefully it will be something that people respond to. You also want to try and pick something that’s within your skill sets so that you can do a good job and get it done. Hopefully it will represent you from a skill point of view as well as being a strong film in itself. You should also keep it short enough so that you can do a good job.

Q: If a student came to you and said “I want to start my own business” what would you tell them?

Sue: I would tell them “GO FOR IT! Go down to the state board and take out a business license.” It is incredibly easy to start a business and you should. The hardest part is finding people to pay you for your work but it allows you to be unique when you have your own thing going.

I would also tell them that the industry is changing all the time. You should never look at the prevailing reality. Your “now” is the creative vision you have within you. Although I try to avoid saying “you are the future,” … you really are the future. Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain. I really believe that.

Q: What was it like for you coming from Disney and transitioning to your own studio?

Sue: When I was at Disney, some of the Nine Old Men were still working there. They were incredibly friendly and welcoming. They loved the new artists coming in and were always supportive.

But, then there was the political structure at Disney at the time, which was not as supportive. Many people that went through that studio were laid off or fired because of that political structure. I saw a lot of people who were laid off from Disney at the time just because they had strong ideas. So many people came and went that they used to call Disney a “clearinghouse for talent.” It’s like this quote I once read, “Reasonable men expect to adjust to the world, unreasonable men expect the world to adjust to them, therefore all progress is made by unreasonable men.” Every one of those people that left or got fired created the “new reality” because it was impossible for them to do so in the studio system.

Q: So you were two people who left and started your own studio where you made Technological Threat. How did Technological Threat come about?

Bill: I’ll never forget the day. We had just paid for this software to develop a TV show called Ultracross when it got cancelled. All of a sudden this show—that was supposed to be paying all of our bills—was gone.

Steven J. Campbell Productions was generous enough to let us use the offices for a few months. Since no one had ever combined 2D and 3D animation before we figured we should at least create a demo since we had the equipment.

So we decided to do a short film. We had three employees and we quickly boarded an idea. Brad Bird (director of The Incredibles) came in and gave us really great notes. So we revised the boards and we started cranking out this movie. We had a lot of friends in the business and we asked them all to animate a scene. Most of them worked for free.

With a loan from Sue’s father, we were able to buy our very first computer. This computer had 4 MB of RAM, a 700 MB hard drive and it cost $57K. This ONE computer was going to do the entire short. It was the only computer at the time that could do this kind of work.

Then we bought these HP machines called “plotters” that would model an image on the computer, turn it into a line drawing and then print it out on paper. Then we could seamlessly combine these with hand-drawn animation.

Q: Did you have a sense that this film was groundbreaking?

Bill: Well, we would bring people in to look at the plotter. And I remember it was like they were looking into the abyss. It was like they were seeing their own death. The computer was drawing pictures and we couldn’t draw as fast as it could.

Q: And this was the analogy of your film?

Bill: Well that’s the irony of it. That’s where I got the idea. People that saw the plotter starting thinking, “wait a minute, I’m going to be replaced!” I said, “If all of our friends are worried about being replaced by the plotter why don’t we do a film about hand-drawn characters being replaced by computer characters. And we will create the hand-drawn characters by doing hand-drawn animation and computer characters by computer animation.”

Image from Technological Threat, courtesy of Bill and Sue Kroyer, all rights reserved

Q: There was obviously a Tex Avery influence in Tech Threat?

Sue: Yes definitely. Rich Moore designed the wolves and Eric Pigors designed the robot. It was our philosophy that if you have great design that is everything. You can have wonderful animation but if the design is not great it won’t work.

Bill: The Tex Avery/Warner Bros. influence was to depict the quintessential hand-drawn animation. What could be more symbolically organic than Tex Avery’s wolves vs. the Computer Animation— which was stiff and generic like the Robots.

I wanted to model the environment after Frank Lloyd Wright’s Johnson Wax Building in Wisconsin (where Sue was from). It had a cool design with a big open office space with desks. I saw it and I said, “That’s the scene in our movie.” Since this was a movie about workers being replaced by robots it fit well.

Image from Technological Threat, courtesy of Bill and Sue Kroyer, all rights reserved

Q: How did your traditional animation training help?

Bill: Since we were trained as Disney animators, we understood the sensitivity of the 2D world. Our traditional training helped with timing and motion. The computer tools were very primitive and difficult to use. Since I had the ability to visualize the motion, I had the patience to comprehend how to use these tools to get the end result I wanted.

When we finished, Terry Thoren asked to use the film in an animation compilation called “The Tournée of Animation.” Then Technological Threat started winning at film festivals (Monte Carlo, Annecy). Based on those wins we were able to submit for the Oscar. I remember Terry called me up and said, “I think you’re going to get a nomination,” and I said “Are you serious?” Sure enough, our very first film gets an Oscar nomination.

Q: So, in retrospect … was the threat of tech good or bad? What do you think of the impact of computers on animation? Has it been a good thing or a bad thing or just something different?

Bill: Technology is totally a good thing because it has given rise to a totally new art form. Animation has been pushed into a world where it’s never been before. Technology is never a bad thing; it’s how you use it that makes it good or bad. In the hands of good artists it can do wonders.

Q: Technological Threat is about computers taking over pencils. If you did Tech Threat today what would it be about?

Bill: It would probably be about Stereoscopic. I was actually thinking of doing a sequel called Stereoscopical Threat.

We will be looking for the sequel.

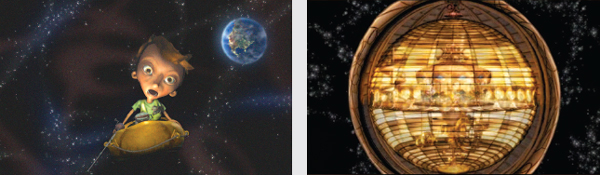

The Ideas Behind Moongirl: An Interview with Mike Cachuela

Mike Cachuela is a director and artist who has contributed visual design and story development to some of the best-loved animated films of the last twenty years. His credits include Coraline, Toy Story, The Incredibles, Ratatouille, FernGully: The Last Rainforest and The Life Aquatic with Steve Zissou. Mike was also part of the effects team nominated for an Academy Award for The Nightmare Before Christmas. He joined Laika in 2005 as a Director of Story for features. In collaboration with Henry Selick, he served as Head of Story on the award-winning short Moongirl. Mike has made several short films for the festival circuit and he is currently developing a feature film based on his own original idea.

Q: What is the basic premise for Moongirl?

Mike: Moongirl is a story that answers the question, why does the moon light up? How does that work? And it’s not what you think. It’s not scientific. It’s just a kid with fireflies … and candles.

Q: What was the inspiration for the story?

Mike: When Henry Selick and I came to the studio there was a young animator, Mike Berger, who had come up with the basic concept about a girl who lives on the moon. I believe that the studio had already completed an iteration of the idea in storyboards. In the original version the little girl fished for stars.

Q: So when you came on board, was the story written?

Mike: The inspiration was there, but Henry re-imagined it. Henry had the idea that the girl lived inside the moon and she regulated some kind of clock that lit the moon. And she had to battle creatures from the dark side of the moon. No one has ever seen the dark side of the moon so that gave us the opportunity to create some curiosity there. What lives there? What do they want? And Henry’s idea was that there were these shadow creatures, the Gargaloons, who wanted to extinguish the light of the moon.

Q: So how do the fireflies come into the story?

Mike: Henry wanted this kid, Leon from the bayou, to bring fireflies to the moon. Fireflies are this magical source of light and they are the primary element needed to create moonlight.

Coincidently, I had never seen fireflies until about a year after we did the film. We don’t have them on the West Coast. I was in Virginia when I saw them. At first I thought they were sparks in the air. I had no idea. I was blown away. The Virginians were just laughing at me.

So anyway, Leon likes to fish at night. He catches fireflies to use as bait. The fireflies catch the attention of this starry “delivery” catfish that brings Leon and his fireflies up to the moon where he discovers Moongirl and helps her fight the Gargaloons.

Q: How did you come up with the ending?

Mike: The ending of the story? Well, as we developed the story, we never really had an answer for what happens after the kids light the moon. How do they get along? Do they stay forever, happily ever after? What happens? I think it was during a brainstorming session that I came up with the “changing of the guard” idea where Moongirl’s stint is done and Leon is left on the moon.

This could have been going on since the beginning of time. Select a kid with a light source and recruit them. This idea has a little bit of that fear element to it—which I think every good story should have— that you never know when it is your time to go to the moon. I don’t think we thought about how distressing it would be for Leon’s parents! I’m hoping he returned in good shape after a month or so.

Q: Either that, or all these kids across the Midwest are catching fireflies, just waiting to be taken to the moon.

Mike: Oh, yeah! You know after I saw Close Encounters I would sit out at night and flash flashlights at the stars to see if I could get aliens to come down and pick me up. It had to be better than elementary school on Earth. If the story has that effect on a kid, that is great.

Q: How much time was spent on the development of the story?

Mike: About six months.

Q: What was the preproduction pipeline like for this piece?

Mike: There was a small art department and they also ended up illustrating the book. There were two story artists, besides myself and we had a team that did the pre-viz, the sets, the test modeling and the rigging, once the character designs were finalized.

Q: How did you come up with the style for the piece?

Mike: Henry wanted the moon to be like a paper lantern, with a lighted carousel inside—like a lighthouse. He was obsessed with Fresnel lenses, which are these beautiful exquisitely crafted lenses that have all these facets and grooves. It is a bit of a nightmare for a lighting guy, but those objects dictated a lot of the look.

We also wanted the look to be illustrative. We looked at a lot of storybook illustrations to see if we could make it look like this, or look like that. It was one of the goals to make the film look a little more analog and less of what CG looked like at that point in time.

Q: What, if anything, changed in the story?

Mike: We tried a couple different approaches with the story. At one point, Moongirl was raising star babies in a star nursery inside the moon. Leon had to babysit. Both Henry and I had toddlers, and so we thought this would be funny, with it being very awkward for Leon, you know, for a young guy. But it skewed too juvenile and it became annoying with all these screaming star babies. So we went back to the drawing board.

You know a good story person will want to argue their point of view about a story. And those discussions can get pretty heated. I think a good director will listen to those opposing voices even if he doesn’t like the idea. The discussion is sometimes an indication that something isn’t working in the story. Most people don’t realize that you’re going to go through ten ideas to find the one good idea. And you’re going to have to be willing to let those other nine go.

Q: How did this story get chosen for production at Laika? What was the value in producing a short for the studio?

Mike: The short was basically a move to see if Henry and the studio could work together on something short that wasn’t too involved. And for me, I thought Portland was pretty awesome. The studio had all this stop-motion equipment and they were very eclectic with lots of really talented artists. I was curious what it would be like to work at this studio that had a little bit more artistic integrity than most.

And of course for the studio the short would be a calling card as well. They had done a lot of CG commercials at the time and wanted to set their sights a little higher, do something more theatrical and test their CG pipeline.

Q: What advice would you give someone who was planning their first film?

Mike: Test your story as many ways as you can to get it working. Use storyboards, pre-viz and just tell the story verbally. It will keep you and your team invested in the project.

Keep your ideas simple and the number of your locations and characters down to a minimum. You can always get bigger with your next effort!

The film Moongirl can be viewed on the Laika website at www.laika.com.