Story Background and Theory

We live in story all of the time. We all have stories to tell every day. But telling our personal stories to each other and constructing a story from scratch are two very different things. Usually when we tell stories on a daily basis, we are relating events to one or two other people. When constructing story, we are trying to communicate with a mass audience. When we tell stories to a friend it is because it is important to us or to them. When we construct story, we are moving not just an individual, but an audience. The goal then becomes to make the personal universal.

Before we can begin, we need to understand the background of story and how that background lays the foundation for what we want to make: a story for an animated short film.

What is a Story?

Screenwriter Karl Iglesias has a very simple definition of story: “A story has someone who wants something badly and is having trouble getting it.”1

This definition determines the three base elements necessary for a story: character, character goal, and conflict. Without these elements, story cannot exist.

- Character. This is whom the story is about and through whose eyes the story is told.

- Goal. This is what the character wants to obtain: the princess, the treasure, the recognition, and so on.

Conflict. Conflict is what is between the character and his goal. There are three forms of conflict:

Character vs. Character

Character vs. Character Character vs. Environment

Character vs. Environment Character vs. Self

Character vs. SelfConflicts create problems, obstacles, and dilemmas that place the character in some form of jeopardy, either physically, mentally, or spiritually. This means that there will be something at stake for the character if they do not overcome the conflict.

The other elements of story include:

- Location. This is the place, time period, or atmosphere that supports the story.

- Inciting Moment. In every story, the world of the character is normal until something unexpected happens to start the story.

- Story Question. The inciting moment will set up questions in the mind of the audience that must be answered by the end of the story.

- Theme. Themes are life lessons. Stories have meanings. A theme is the deeper meaning that a story communicates. Common themes include: be true to yourself; never leave a friend behind; man prevails against nature; and love conquers all.

- Need. In story there will be what a character wants—his goal. Then there will be what the character needs to learn or discover to achieve his goal.

- Arc. When a character learns there will be what is called an emotional arc or change in the character as the character moves from what he wants to what he needs.

- Ending/Resolution. The ending is what must be given to the viewer to bring emotional relief and answer all of the questions of the story. The ending must transform the audience or the character.

Why Do All Stories Seem the Same?

With so many different story elements and seemingly infinite ways to combine them, why do all stories seem familiar? Nearly every story told follows the same structure and formula with similar characters, themes, and conflicts.

The Universal Story

From the turn of the nineteenth century on, there are documented discussions between writers and theorists who noticed that the similarities in story went beyond specific regions, cultures and time periods.2 Some of them theorized that this was because mankind had similar natural phenomena that needed to be explained. This might be the reason for similarities in theme, but didn’t explain the similarities in story and plot.

All of these stories followed a three-act structure that Aristotle, nearly 2,300 years ago, called plot. Plot is the sequence of events and the emotions necessary to move the audience through the story. In the first act, pity and empathy must be established for the hero so that the audience cares about him and will engage in his pursuit. The second act is the scene of suffering and challenge, creating fear and tension surrounding the hero and his challenges. In the final act, fear and tension are released by catharsis, the emotional release that allows for closure to end the story.3

In the twentieth century, Joseph Campbell, an American mythology professor, writer and orator, found that there were universal images and characters in one story shared by all cultures over time. Because this story occurred again and again, he called it the monomyth—the one story, the universal story.

The monomyth is appropriately called the Hero’s Journey. Campbell’s theory has many stages, but they can be summarized as follows:4

- Introduce the Hero. The hero is the character through whom the story is told. The hero is having an ordinary day.

- The Hero has a Flaw. The audience needs to empathize with the hero and engage in his pursuit of success. So the hero is not perfect. He suffers from pride or passion, or an error or impediment that will eventually lead to his downfall or success.

- Unexpected Event. Something happens to change the hero’s ordinary world.

- Call to Adventure. The hero needs to accomplish a goal (save a princess, retrieve a treasure, and so forth). Often the hero is reluctant to answer the call. It is here that he meets with mentors, friends, and allies who encourage him.

- The Quest. The hero leaves his world in pursuit of the goal. He faces tests, trials, temptations, enemies, and challenges until he achieves his goal.

- The Return. The hero returns expecting rewards.

- The Crisis. Something is wrong. The hero is at his lowest moment.

- The Showdown. The hero must face one last challenge, usually of life and death against his greatest foe. He must use all that he has learned on his quest to succeed.

- The Resolution. In movies this is usually a happy ending. The hero succeeds and we all celebrate.

Example:

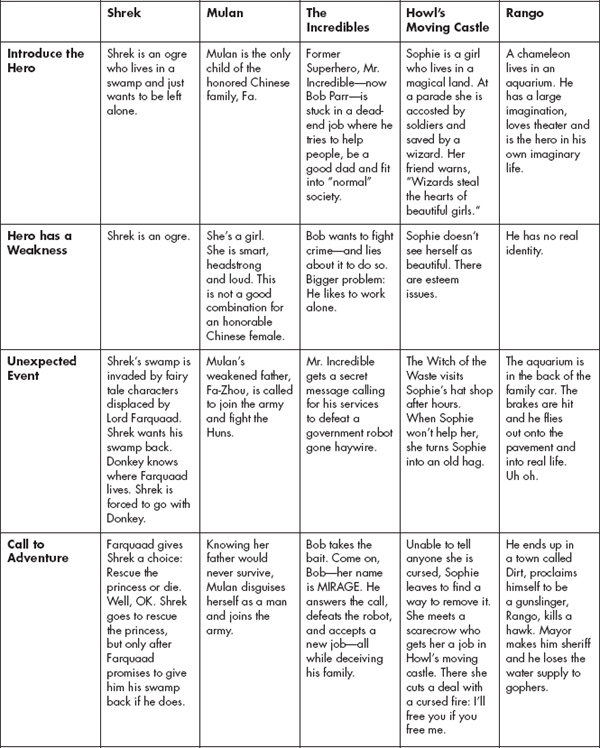

Table 1.1 Feature Film Plots Against the Hero’s Journey

Disney films have driven home the opportunity of the individual to succeed, and above all, it is personal success that we celebrate. In Disney films there is a clear hero who fights a clear villain. Nearly all of the classic Disney movies are excellent case studies of the hero’s Journey.

On the other hand, Pixar films follow every aspect of the structure except that of the hero. If we define a hero simply as the eyes through which the story is told, then Pixar, too, more or less fits the formula. If we define the hero as the one who succeeds and whose success we celebrate then this changes the dynamics when we look at a Pixar film.

In Pixar films, from A Bug’s Life on, the role of hero is more often played as if it were a baton passed among characters.5 For example, in Finding Nemo, it is Marlin’s quest to find Nemo. But Marlin fails. He begins to return home without his son. It is Nemo who brings himself home and it is Dory’s role to reunite Nemo with his dad. At different times, Gill is the hero and Dory is the hero.

Miyazaki also orders the events in a classic structure. However, in most of his stories, the identification of good and evil is not clear. For Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli, evil, if it can be called that, is that which dwells within us. His stories have conflict that is often more internalized. Success comes through personal resurrection. Through the character’s personal transformation, the peace in society is restored.

Character Archetypes

In movies there are definite character roles that appear repeatedly in all of the stories. These roles come from character archetypes. An archetype is a pervasive idea or image that serves as an original model from which copies are made. For our purposes, this means that there are baseline character traits that any surface or costuming can be placed upon. The hero is a baseline that can be an obvious superhero (Mr. Incredible); or a more subtle hero (an ogre, Shrek; a girl, Mulan; a woolly mammoth, Manfred); or a character that grows into a hero (an iron giant; a boy, Hiccup; a lizard, Rango, and so on).

The term first comes from Carl Jung, a twentieth-century psychoanalyst who studied dreams and the unconscious. Jung found that there were recurring images and themes running through the dreams of his patients that were so similar that they could not come from individual conflicts. He believed that these images originated in the collective unconscious of all men. And he called these images archetypes.

Jung’s four archetypes, attributes common in everyone, are: the female, the great mother; the male, the eternal child; the self, a hero, wise old man; and the shadow, which might be a trickster, and so forth. They were the different ways in which the individual would see themselves. And these formed the basis for the stories that his patients would tell.

In the stories of feature films we find the same thing. There are archetypes that form the basis of nearly all characters we watch. Chris Vogler, in his book The Writer’s Journey, identifies seven archetypal characters found in most feature films:

- The Hero—the character through which the story is told.

- The Mentor—the ally that helps the hero.

- The Herald—this character announces the “Call to Adventure” and delivers other important information. This role sometimes shifts from character to character.

- The Shadow—this is the villain or major protagonist. Sometimes, as in Miyazaki’s films, the shadow resides in the character himself.

- The Threshold Guardian—this is a character, passageway or guardian that the hero must get past to proceed on the quest, or to retrieve the object of the quest.

- The Trickster—this character is usually the comic relief. He sometimes leads the hero off track or away from the goal.

- The Shapeshifter—this character is not who he appears or who he presents himself to be.6

Archetype Silhouettes by Gary Schumer, Ringling College of Art and Design

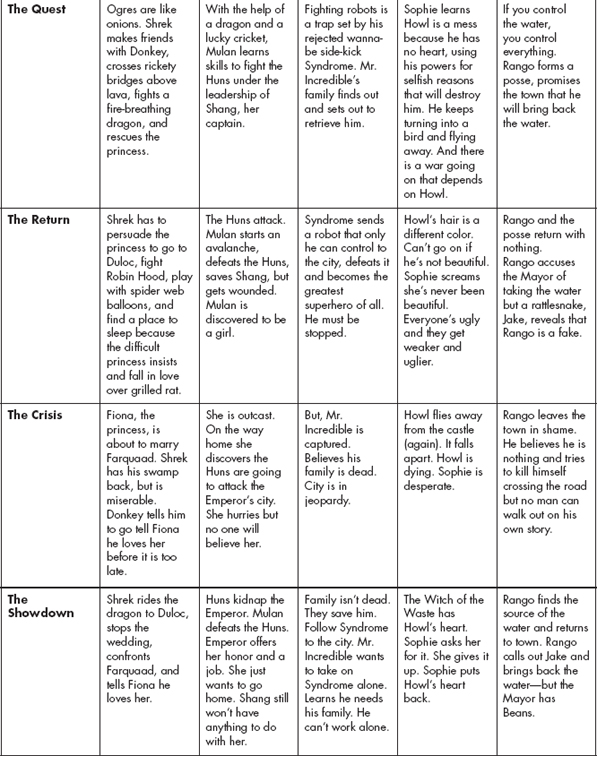

In Table 1.2 we can see how these characters manifest themselves in selected movies. Sometimes more than one role is fulfilled by the same character.

Table 1.2 Character Archetypes in Feature Films

It is important to note that an archetype is not a stereotype. A stereotype is a simplified generalization about a specific group. For example: All elderly people are forgetful; all Asians have high IQs; all French are romantic; all African-Americans can dance; etc.

An archetype, on the other hand, is a character attribute that can manifest itself in any human (or in animation, nonhuman) body and that is a recognizable icon by the audience. For example, in Iron Giant, the giant is the child that has to be taught. In Ice Age, Manfred becomes the great mother—of both the Indian child and the “herd.”

Universal Conflicts

Conflict is the situation or problem in the way of the character’s goal. It is a dilemma that creates tension for the character. It is something that puts the character in jeopardy.

With all the infinite problems and predicaments that face mankind, you would think that the expressions of conflict would be infinite. But again, we find recurring motifs of conflict. In fact, these motifs occur so often that instead of recognizing these as forms of conflict, we categorize them into types of stories:

- Brains vs. Brawn. Pitting intelligence against strength.

- Rags to Riches. Personal struggle for achievement.

- Good vs. Evil. Equal forces against each other.

- Role Reversals. Allow us to see through the eyes of the “other” and experience how others live.

- Courage and Survival. This conflict is usually environmental. There is a disaster or disease that must be overcome.

- Peacemakers. Underdog stories where the “good” are those who protect the weak or stand up for what is right.

- Tempting Fate. The conflict arises when the hero goes against the established order (the law, God, nature), sometimes for the greater good, but more often for personal gain.

- Fish Out of Water. A character/characters are transported to a different time or place where they must learn how to survive.

- Ship of Fools. Several well-defined, but different characters must navigate an adventure together.

- Buddy Stories. Focus on the strengths and contrasts of the characters to overcome adversity and become friends.

- Love Stories. Study of romantic relationships that focuses on the trials that bring two people together or tear them apart.

- Quests and Journeys. In these stories, a hero traverses space and/or time to retrieve an object or person only to find themself changed.7

Often, in feature films, there will be one conflict motif that is the main conflict or problem. Then there may be secondary motifs that emerge in the subplots.

Universal Themes

Conflicts are not themes. Stories have meanings. They are not just a series of events. They communicate something to us that is larger than the story itself. The meaning or dominant idea of the story is called the theme.

For example, DreamWorks’s How to Train Your Dragon is a story about Hiccup, the scrawny but brainy son of Stoick, a strong but not brainy Viking chief. Hiccup ends a 300-year-old feud with fire-breathing dragons, taking on assumptions about dragons and what it means to be a Viking. It is basically a David and Goliath/Brains vs. Brawn/Underdog story, but these are the conflicts, not the themes. Throughout the film, Hiccup’s father references Hiccup’s lack of Viking qualities and Hiccup says, “You just gestured to all of me.” The Vikings are in battle with dragons, considering them pests until Hiccup discovers that a Night Fury—the most mysterious and powerful dragon of all—is as afraid of him as he is of it.

Hiccup learns that real strength is on the inside and “all of this” is enough. These are themes. Themes are life lessons.

Because themes are life lessons, they are often based on human needs. These needs fall into three categories:

- Physical needs

- Mental needs

- Spiritual needs.

Within these three categories we find basic needs:

- Food

- Shelter

- Security

- Acceptance

- Stimulus

- Love

- Order.

This limited number of needs forms nearly all of the themes of our stories.

At the end of Mulan, the Chinese Emperor admonishes Mulan: “I have heard a great deal about you, Fa Mulan. You stole your father’s armor, ran away from home, impersonated a soldier, deceived your commanding officer, dishonored the Chinese army, destroyed my palace! … and you have saved us all.” As Mulan heads home, the Emperor tells Shang (Mulan’s commanding officer and love interest), “A flower that blooms in adversity is the rarest and most beautiful of all.”

In Pixar’s UP, Carl is an elderly gentleman adjusting to life without his wife, Ellie. He is lamenting that “life” got in the way of fulfilling Ellie’s dream of adventure, when Russell, a young wilderness scout, tells him about getting ice cream and counting cars with his father. He says, “The boring stuff is what we remember most.” And Carl finds that in Ellie’s adventure book about the stuff she was going to do in her life turns out to be about the life they had together.

For other movies, theme is not so obvious. Sometimes, if you look at what the main character wants and what he needs to learn it often points you to the theme. It is not the objective of a movie to have the audience leave the theater spouting themes. It is the job of the film to move them unconsciously toward the theme through their emotions. As a creator of films, however, it is necessary to know what you are trying to say in your film.

Brian McDonald, in his book Invisible Ink, makes a distinction between plot and theme. He compares the movies E.T. and Iron Giant. Both are timeless stories of friendship that seem to have similar plots. In both there is a lonely boy who befriends a being from outer space. As the boy bonds with the being, it learns to speak English and the boy in turn tries to teach it what it means to be human. The government wants to capture the potential threat and that pursuit results in life and death possibilities for both the boy and the being. So what is the difference?

In the beginning of E.T., Elliott says something hurtful to his mom and his brother declares, “When are you going to grow up and learn how other people feel for a change?” This is the story question and theme of the movie. The entire film is about Elliott learning to empathize with others. When Elliott finds E.T., he declares “I’m keeping him,” without any regard to the feelings or needs of the alien. But as the movie progresses, he feels what E.T. is feeling until eventually he is able to send E.T. home.8

In Iron Giant, however, Brad Bird raised the question, “What if a gun had a conscious and didn’t want to be a gun anymore?” We learn that “You are what you choose to be.” This is what Dean, the scrap-metal artist, tells Hogarth Hughes as he rants about his classmates. Hogarth then teaches it to the Giant who repeats it to himself. At the climax of the film, the Giant has transformed into a very large, defensive weapon when Hogarth reminds him that he doesn’t have to be a weapon. The Giant chooses to be a hero—like Superman.

The two stories are amazingly similar in plot, but what we learn from the theme is distinctly different.

Likewise, movies can be very different in plot but teach us the same lessons.

Rango is similar in theme to Iron Giant. Rango is a chameleon who has no identity. He lives a solitary life in an aquarium where he has an active imagination and is the hero of his own life. One day he is propelled into the real world and wanders into a desert Western town with a water problem. He is asked repeatedly, “Who are you?” to which he responds, “I could be anybody.” Then he takes on a persona of a hero until he is discovered to be a fake to which he responds, “I am nobody.” He rallies at the end, deciding to return and help the town declaring, “I’m going back because this is who I am.” You are who you choose to be. He finds his true path.

A theme is what your audience learns from watching your film.

Originality in Story

If there are limited themes, conflicts, structures, and character types, what makes each story unique?

Robert McKee states that story is about form, not formula.9 While the themes, conflict, structures and archetypes may be the same, what is unique is a compelling character and emotionally driven sequence of events. Each character will react to events in a different way. Observing how someone else reacts is compelling. It is why we watch.

The other thing that makes a unique story is character desire. In theme, we talked about basic character needs. But often what we want or desire is not what we need. Therefore, conflict in story can be about desire vs. need. Desire is often unrealistic. It is complicated by greed, pride, ambition, fear, laziness, apathy, and so forth. To be successful, characters must overcome desire and learn what they need.

Example: Shrek wants (desire) to be left alone, but what he needs to learn is that not only does he need others, but he deserves others. Manfred just wants to be left alone, but he finds he needs a herd. Mr. Incredible works alone, but learns he needs his family and friends.

What makes a story interesting for an audience is the ability to engage with a character and either vicariously, voyeuristically or viscerally, watch the unique ways that that character reacts to the problems and obstacles they confront.

Making the Long Story Short: The Difference between Features and Shorts

Beyond the obvious differences in running time, scope, complexity, and resources, the animated short requires a directness, clarity, simplicity, and economy of plot and assets not found in feature films.

Initial ideas for a short are often too big, too complicated and cover too much territory because most of our references are based on the Hero’s Journey.

In the Hero’s Journey, the characters (many of them) meet with conflict (several events in several locations), until they reach a crisis (of monumental spiritual or physical proportions) where they learn a lesson (the many themes and subtexts converge), make a decision (which calls for more action) and succeed (usually in celebration with the many other characters).

For the individual filmmaker, the short should have one theme, concept or idea that the piece communicates and one conflict that intensifies or gets worse. It should have one or two characters, one or two locations, and only the props necessary to populate the scene appropriately or drive the story.

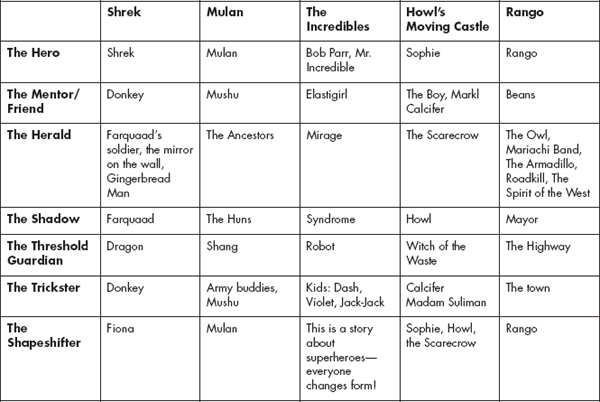

The inciting moment, the moment when something unexpected happens for the character, usually occurs within the first 10 to 15 seconds. In A Great Big Robot from Outer Space Ate My Homework, we enter the film after the alien has eaten the homework and when the boy is rushing to tell his teacher.

A Great Big Robot from Outer Space Ate My Homework, by Mark Shirra, Vancouver Film School

In the short, the character will arc, which means he will change emotionally from the beginning to the end. But he doesn’t always learn, make big decisions or even succeed. Sometimes it is enough to retrieve an object, understand an environment, solve a problem, reveal a secret, or discover something. Shorts can be as small as a one-liner or a single event as in Caps.

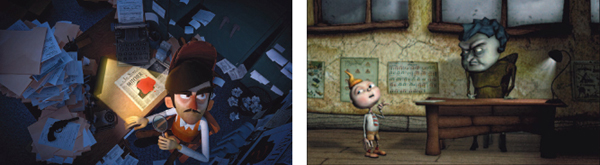

Caps, directed by Moritz Mayerhofer and Jan Locher, Filmakademie Baden-Wuerttemberg, Germany

In Caps, four hooded and colored figures have offerings for an Altar. There is a green one who is clearly behind. He has a different character and tempo. Red, Blue and Yellow all offer their gifts to the Altar, but when Green arrives he has drunk most of his offering. Yet he can pull out a scooter and color the world.

Remember our most basic definition of a story: a character who wants something badly and is having trouble getting it. When you are looking for ideas, this is still the basis of what you are looking for, only smaller.

Let’s work this definition a little bit further: The short story has ONE character that wants something badly and is having trouble getting it. That “trouble” is, at most, ONE other character or environment that causes conflict. The resolution to the conflict communicates ONE specific theme.

This will translate into the following structure:

- It is an ordinary day

- Something happens that moves the character to action

- A character wants something badly

- He meets with conflict

- The conflict intensifies until

- He makes a discovery, learns a lesson, or makes a choice

- In order to succeed

That sounds a lot like the Hero’s Journey. The difference is in the singularity of the conflict.

The Disney short Chalk is a great example of this.

© Disney. For Training Purposes Only—Property of WDAS 2010 Talent Development

First, viewers are dropped into a girl’s 3D “real” life. Her street is a line of monochromatic row houses. It is hot outside. That is the first major conflict. It is here that she is creating her fantasy world of color, and more importantly, a place where she can get some relief from the heat. She draws a kiddie pool with sidewalk chalk, and slips into a daydream as she visits a place that is cool.

In this 2D fantasy water world, a youngster’s imagination can run wild, and she interacts with colorful fish, far from her other world where there were no other living things.

Then she meets a whale, a potential threat and the second major conflict, which surprises her by singing, “Din-ner!” This shocks her into returning to the real world and the realization that what she heard was her mother.

Stories need rising conflict. In this piece, the drama builds gradually toward the supreme conflict, without the audience really seeing what is happening. First, she has a surprising encounter with a jellyfish, and then she is spun around by a whoosh of a school of fish, and then the slow looming arrival of a very large whale.

More importantly, the encounter with this huge mammal is the intellectual pivot point of the piece. The whale’s size, stealthy movement and teeth combine to give the audience some sinister clues about its relationship to the girl, and when it says, “Din-ner,” the worst is feared. But there are contradictory clues. The whale’s voice is high and feminine, some teeth are missing, its mouth hangs open lazily. Not what you would expect from a killer whale.

In the end she heads back to her real world having taken us along to her fantasy world.

So let’s look at this in terms of our structure:

- A little girl is playing outside

- The sun glares on her and she wants to get out of the heat, so she draws a pool and slips inside

- She swims with fishes until a jellyfish bounces on her stomach

- She gets knocked around by a school of fish

- A huge whale arrives that seems to want to eat her for dinner

- She discovers it is her mother calling her

- And she runs home leaving a colorful world of chalk friends behind.

When reading the following chapters, keep this kind of simplicity in mind. One good, simple idea is the key to making a solid short. The simpler the better because you don’t have much time to say what you want to say, but more importantly, the viewer does not have much time to grasp what you are trying to say.

Summary

Why do we tell stories?

- To entertain

- To teach

- To compare our existence to others

- To communicate with others

- To see the world through the eyes of others

- To learn how to be human.

Many stories seem to be the same as other stories because:

- There is an archetypal story structure

- There are a limited number of archetypal characters

- There are a limited number of conflicts

- There are a limited number of themes.

Original stories are created through the audience’s engagement with unique characters and the way that they react to and solve the conflicts they encounter.

As filmmakers, we deliver emotion. It is through emotional engagement that we move an audience.

When making the animated short, the story needs to have limited characters, limited locations, one conflict, and one theme.

Additional Resources: www.ideasfortheanimatedshort.com

- Working in Collaboration: The Disney Summer Associates Program: An Interview with Terry Moews

- Industry Interview: Story and Humor: An Interview with Chris Renaud and Mike Thurmeier, Blue Sky Animation Studios

Recommended Reading

- Joseph Campbell, Hero with a Thousand Faces

- Chris Vogel, A Writer’s Journey

Notes

1 Karl Iglesias, Writing for Emotional Impact, WingSpan Press, Livermore, CA.

2 Christopher Booker, The Seven Basic Plots, Continuum, New York, NY, 2004, pp. 8–10.

3 http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/poetics.1.1.html. In addition to Plot, Aristotle defined four other elements of story. These are 2) Thought, which is dialogue; 3) Diction, the way the dialogue is said; 4) Sound, the soundtrack; and 5) Spectacle which is the equivalent to special effects. Of these elements Spectacle was the least important. It seems that even Aristotle realized that effects are only good if the audience is not distracted by them.

4 This is a modified version of the Hero’s Journey as defined by Chris Vogler in his book, The Writer’s Journey. In his book is an excellent chart that compares Vogler’s Map of the Hero’s Journey and Campbell’s. See Chris Vogler, The Writer’s Journey, Michael Wiese Productions, Studio City, CA, 1992, p. 16.

5 Ed Hooks, Newsletter, Acting Notes, CA.

6 Chris Vogler, The Writer’s Journey.

7 John Douglas, Glenn P. Harnden, The Art of Technique; An Aesthetic Approach to Film and Video Production, Allyn and Bacon, A Simon & Schuster Company, Needham, MA, 1996, pp. 16–20.

8 Brian McDonald, Invisible Ink, Libertary Editions, Seattle, WA, 2003–2005, p. 22.

9 The original quote is: “Story is about eternal, universal forms, not formulas.” Robert McKee, Story: Substance, Structure, Style, and the Principles of Screenwriting, Regan Books, 1997, p. 3.

Making the Animated Short: An Interview with Andrew Jimenez, Pixar Animation Studios

Andrew Jimenez went to San Diego State University. His first big break was on Iron Giant after which he moved to Sony Pictures to work on the first Spider-Man movie as a story reel editor and storyboard artist. That job led to a move to Pixar with Brad Bird to be a co-director of photography on The Incredibles. Most recently, Andrew worked on the animated short, One Man Band.

One Man Band, directed by Andrew Jimenez and Mark Andrews, Pixar Animation Studios

Q: How do you recognize a good idea for an animated short?

Andrew: Feature films and shorts are two completely different types of stories. When Mark Andrews and I were trying to come up with the idea for One Man Band, even when we were considering very un-fleshed-out ideas, it was clear that, OK, this idea belongs in a feature film and then this idea belongs in a short film.

It’s a strange analogy to make, but a good short film is like a good joke. It has a great setup, gets to the point, and pays off right away. And it doesn’t demand too much in terms of where the story has to go. It gets to the idea right away. You get it. Even if it takes you somewhere different than what you expected, it gets there right away too. It’s just very simple. And it’s about one idea. It can have multiple characters, but it has to be very clear, because in three or five minutes you don’t have time to really develop all these side stories and other plot lines.

To use the “joke” analogy again, if my timing isn’t perfect and I go on a little bit too long, I can ruin it. I also think it’s almost a little bit harder to tell a short film story because you don’t have the luxury to develop anything deeply, but yet it should be as meaningful.

It’s funny because so many short films aren’t short anymore. I think the biggest pitfall is that they are always the first act of a feature film, or they seem to be used as a vehicle for: “I’m just making this part of my bigger idea, but I’m using this to sell it.” I’m always disappointed when I find out a short film has done that, because it ignores what is so wonderful about making short films.

Q: When you’re building the story, how do you stay focused on one idea?

Andrew: One of the most important parts is the pitch. When your students or any new storyteller tells somebody else the idea, whoever is listening and/or the person pitching should really pay attention to how they are pitching.

I’ll use One Man Band as an example:

There’s a guy on a corner, and he’s playing music. He’s pretty good, but not really that good, and there is another musician that he is going to battle. That’s the story. That’s it. The second I start pitching and telling, or describing events to the story that sort of breaks out of that little quad that this movie takes place in, that’s the point where I start to get a little worried. The entire pitch should never break from that initial setup.

I think you should be able to pitch your idea in really 15 seconds. Even in One Man Band the film never really breaks out away from what’s presented in the first 15 seconds of the movie.

And it gets back to the joke analogy, which is a silly analogy, but I think it really makes the point well.

If I’m telling a joke, every beat of the story has to be right on the spot. In the feature film I can wander a little bit, lose you a little bit, I have time to get you back, but in the short film, if I lose you, there is no time to get you back. In the short film, if I go one beat too long, I can ruin it.

For example, if I start setting up giving too much background and explaining too much, then you, as an audience, start getting bored, and by the time I get to the punch line, it’s like, uh, OK, that wasn’t funny, because you gave me way too much information.

I keep using the analogy of telling a joke. That is not to say a good short film has to be funny. It’s just a way of illustrating how important timing is in the short film format.

Q: Is it hard to be funny?

Andrew: Yes, absolutely. I know if I’m trying to be funny, then I should stop right there. Stories are just like people. The funniest people never really try to be funny, they’re just really funny. And in story, the funniest stories come out of the situations.

The only thing with One Man Band that we started with before we created the story was that we knew we wanted to tell a story about music. There was a theme about what people do with talent and how people view other people that may have more talent than they do. Humor came out of story development but we never tried to do humor before we even knew what our characters were doing in the story. It is what the characters do—the acting—that makes it funny. Of course their designs played a big part of that too.

Everything comes out of story. Whether you try to be depressing or sad, or funny, humorous, or make a statement, I think the second you try to do that without arriving at that through your story, then it’s kind of like telling your punch line before your joke.

Q: What was the hardest part of making One Man Band?

Andrew: For One Man Band the hardest thing—it’s true for the features, too—was that after Mark and I got the green light just to come up with ideas (and we were so ecstatic about that) was to actually come up with the ideas.

There’s no science to coming up with a story. You can’t say, “All right, go—come up with a story.” So, Mark and I started having lunch every day. We started talking about things we had in common, things we liked, things we didn’t like in other movies.

I had this book I called “The Idea Book,” and I wrote down all the ideas we came up with, about 50. One of the common themes in all these little ideas was music—and competition. I have been an avid film score collector since I was a child and have always wanted to tell a story where music was our characters’ voices.

So we started developing and working around that theme. That time was the hardest part of the entire production of One Man Band—really getting that theme through the progression of the story. Because if you don’t have that locked down and perfect, no matter how good the CG is or the acting is, you’re never going to save it.

Don’t worry about your perfectly rendered sunset, and shading and modeling of the set. It’s the characters and their story. People will forgive so much if they really believe and love your characters and your story. When André and Wally B. was shown at SIGGRAPH for the first time many years ago, most people in the audience didn’t realize it wasn’t finished because they were so involved with the characters.

Q: What advice do you give to an animator making their first short?

Andrew: My advice would be: don’t overcomplicate it. Just find one idea that you want to tell, stick with that and trust it. If it’s not working ask yourself why. Don’t think you have to pile a bunch of other stuff on top of it to make it work and make it longer. Students, especially, will pack so much stuff into the film to try to show what they can do and to make the amazing film. I know I learned so much more by making several shorter films in the span of a year instead of making only one gigantic opus.

I know at Pixar, when we look at other short films, the thing we respond to the most is a short simple idea that grabs us, that we get to react to, and then it lets us go.