Chapter 2. Behavior and Individuals

During her first week, Lydia decided to sit back and simply observe communication between members of the team. She first attended a meeting where the team was discussing the design of the system.

Lydia noticed that Sean was dominating most of the conversations. As a result, most of his ideas were the ones that defined the design. Carl and Lisa contributed to the discussion and seemed to be having fun. David, who was the most experienced developer in the group, was overpowered by the conversations and could not seem to get a word in edgewise. So he did not offer too much assistance to the meeting. Eric seemed quite uncomfortable when Sean put him on the spot asking his opinion on the maintainability of the design. Ravi wanted to get into some of the details behind design decisions to feel comfortable that they would work, but Sean seemed to want to drive things fairly quickly.

By the end of the meeting, you could sense a bit of tension among members of the team, and although they walked away with a design, Lydia could tell not everyone felt comfortable with the approach. The bigger issue was not the design, however, but that the team was not acting like a team. Some key opinions were never spoken. And individuals were getting frustrated with one another.

Lydia knew her first step to increasing the team’s performance was to get the team to start understanding each other’s behaviors and to modify their communication styles to work more effectively as a team.

Communication Framework

If you ask people to define agile, you will probably get as many different answers as the number of people you ask. To make it simpler, what if you ask them to abstract the top three definitions in just one or two words? Most would include the words “communication” or “teamwork” in their definitions.

The Agile Manifesto indicates, “Individuals and Interactions over Process and Tools,” and one of the Agile principles states, “The most efficient and effective method of conveying information to and within a development team is face-to-face conversation.” So, if agile is, to a large degree, about increasing communication effectiveness and the way teams work together, why would anyone begin an agile project without first establishing a communication framework that fosters better communication and teamwork?

Have you ever heard of project teams that successfully start an agile endeavor with much excitement and enthusiasm, but over time, the project falls apart? It is similar to building a house on a sink hole. It appears great at the onset. But after a period of time and when you apply some pressure and stress, the house sinks. To help prevent sink holes on your projects, this chapter discusses a valuable framework for enabling better communication: the history, definition, and importance of this framework are covered.

DISC History

The framework discussed in this chapter is called DISC. You may have already heard of DISC because it has been around much longer than agile and even longer than Lean whose roots date back to the 1930s when Toyota moved from a spinning and weaving company to a car company. You could tie the history of DISC all the way back to 400 B.C. when Hippocrates observed humans and classified four different behaviors.

In 1928, Dr. William Moulton Marston published a book titled, The Emotions of Normal People, in which he described the DISC theory. Over the years, several companies have provided statistical validation and continuous improvements to DISC.

So DISC has been around for a while. But it is only a relatively recent development that it is being applied to achieve greater communication on agile teams. Even though I had been using DISC on my software project teams for many years prior, I had initially heard of the association of DISC with enabling success on agile projects during my Certified ScrumMaster training by Craig Larman in 2006.

DISC Definition

You can think of DISC as a behavioral fingerprint. Everyone’s behavior contains a blend of four elements, but no two people’s blends are exactly alike. It is this blend that drives how individuals behave. To begin to gain an understanding of DISC, it is easiest to simplify it in terms of one’s dominant behavior. That is, if someone’s dominant behavior is a D (with secondary I), you may simply refer to that person’s behavior as a DI. This dominant behavior explains how people will behave and communicate. So what do these letters mean?

The D—Dominator

D’s have a need to accomplish. They are decisive, thrive on challenges, exercise authority, and hold themselves in high regard. D’s have a tendency to deal straightforwardly with people and may interrupt you in mid-sentence. They may be perceived by others as being arrogant, opinionated, or rude. The higher the D, the more intense these behaviors. It should come as no surprise that many CEOs of companies are D’s.

The I—Influencer

I’s have a need to trust and talk. They trust, accept, and like others. I’s enjoy talking and are animated (for example, they tend to talk with their hands or full facial expressions), persuasive, and optimistic. I’s may have a tendency to become emotional or excitable and may be a poor judge of character because they give people the benefit of the doubt. I’s usually see the glass as half full. I’s typically make the best communicators.

The S—Supporter

S’s have a need to support others. They are good team players, avoid attention, have good listening skills, and are deliberate or self-sacrificing. S’s typically build close relationships with a relatively small group of friends. High S’s may not make the smallest decisions. You might walk all over high S’s as long as they feel appreciated. S’s tend to make the best team players.

The C—Critical Thinker

C’s have a need for perfection and quality. They aim for accuracy—and have a capacity for and enjoy concentrating on details. C’s think systematically and are problem solvers. They are typically serious, intense, thorough, and cautious at decision making. C’s tend to set high standards for themselves that are above the norm. They may become critical of others if they do not meet their high standards. C’s typically see the glass as half empty because they want things to be perfect. Our industry is dominated by high C’s who are computer “scientists” or software “engineers.” Coding, testing, designing, and capturing requirements all take analytic skills and close attention to details.

So Why Is This Important?

The next few sections answer this question, including understanding and accepting others, the need to communicate in your own language, and the language of DISC. There is also a section regarding strategies for communicating with others depending on your behavioral profile.

Understanding and Accepting Others

Individuals that understand DISC can perform better on teams by understanding and accepting other team member’s behaviors.

The following story is a real-world example of an event that occurred at a consulting company several years ago. Marcia, the recruiter, was a high D, and John, one of the principal consultants in the company, was a high C. Marcia was frustrated. “I just want a simple answer whether we should hire a candidate that John just finished interviewing, and John said he would need to think about it overnight and get back with me tomorrow,” she said. “I do not understand why I can’t get a simple answer right away. We are under the gun to move quickly.” At the same time, John was equally annoyed at Marcia for being so “pushy,” wanting an immediate answer.

The next day, John provided a long, involved, and detailed write-up describing the candidate interview. John described the elevator simulation problem he had given the candidate. He went on to describe the candidate’s answers in great detail, including the candidate’s ability to use abstraction and design patterns. The detailed write-up went on to describe John’s analysis of these answers and depicted the pros/cons of the candidate’s solution. Finally, John recommended hiring the candidate. Although frustrated that it took so long, Marcia was happy to get a bottom-line answer. She did not actually care about the detailed response but was happy to see a conclusive and positive answer and made an offer to the candidate.

Several months later, both Marcia and John took the DISC assessments and were in a room discussing the results. Both laughed out loud as they immediately reflected on this event. Both Marcia and John understood why they behaved the way they did and realized they could better accept and communicate with one another now that they realized why. From that point forward, Marcia tried to be a little less pushy and give John time to do his analysis to make a decision. And John tried his best to provide a quicker answer. But most important, they understood and more readily accepted one another.

Communicate in Your Own Language

Another reason DISC is so important is because people have a need to communicate in their own language. Although you cannot permanently change your behavioral profile, you can adapt your behavior and communication style to not induce stress on a person with whom you are communicating.

Say, for example, that you were giving a presentation to a leader of a company regarding how much a particular project will cost. How would you modify your presentation if you were presenting to a high D? To a high C?

If you are presenting to a high D, you should give an executive summary first indicating the bottom line of how much the project will cost. Then get into the facts—and be open to skipping some of the details. Otherwise the person will flip to the end of his hardcopy version of your slides (if he has a hardcopy version and may become frustrated if he does not), wanting to know the bottom line.

When presenting to a high C, you should do the opposite. Present all the facts first, followed by the price, perhaps with some type of a traceability matrix back to all the details. Otherwise, the person will feel uncomfortable being hit with numbers without first knowing the supporting data that led you to your conclusion.

The following is another example of a real-world situation. A group had just finished DISC training and were checking into a hotel. There were two clerks at the hotel front desk. One checked in with the first clerk who smiled and asked, “Where are you from? How was your trip?” Another checked in with the second clerk who did not smile, got straight down to business, and asked, “What type of credit card will you be using?”

To an I traveler, the first clerk would appear to be warm, and the second clerk would be a bit of a “jerk.” To a D traveler, the first clerk would be quite annoying and would be wasting time especially considering he is tired and just trying to check into his room. The second clerk would be perceived by the D as being efficient. If the hotel owner knew about DISC, think about how she could potentially increase her guest satisfaction by teaching her clerks how to greet guests based on their body language and communication when walking into the lobby?

The Language of DISC

The final reason that DISC is important is because it enables people to leverage “the language of DISC.”

If everyone has been trained on DISC, it makes for a great and sometimes necessary ice breaker. The following is a real-world example depicting the language of the DISC. This story is about a company in which the CEO was, you guessed it, a high D. The CEO was actually a high DI. When a high D is also an equally high I, that person tends to be seen as charismatic.

There would periodically be times where a group would get together to brainstorm ideas. The CEO would naturally dominate the conversation. He was smart and had a lot of good ideas. But so did others. When the group could not get a word in edgewise, one of them could say to the CEO something like, “Your D is acting up right now.” He knew he was a high D, so he would laugh, and others would get a chance to talk. Without the “language of DISC,” it would be difficult to essentially ask him to kindly shut up. When using the language of DISC, people generally laugh and get the point.

The following is yet another true story. A new project was kicked off with about 20 people in a room—a mix of business stakeholders and project team members. In typical fashion, one of the lead business stakeholders was an extremely high D, whereas one of the senior developers was an extremely high C.

The senior developer made a suggestion to which the main business stakeholder said, “Do you know what your specific role is going to be on the project?” The senior developer did not know how to respond and simply said, “No not exactly.” Of course, on an agile project, there are only three roles (that is, Product Owner, ScrumMaster, and team member), but the business stakeholder did not know that. The business stakeholder actually replied, “Then I do not want to listen to your suggestions.” It was an awkward moment, and the room was silent for what appeared to be 10 minutes. (Although it was only about 10 seconds.) It ruined their relationship, and it was a shame the team was not trained in DISC prior to this initial meeting. Anyone could have easily broken the ice with the language of DISC. It would have taken care of an awkward moment by breaking the silence, and most likely the business stakeholder would have apologized, salvaging that relationship. You can see how the cost of not executing a DISC group session can be costly to a project because relationships can be permanently severed.

Strategies for Communicating

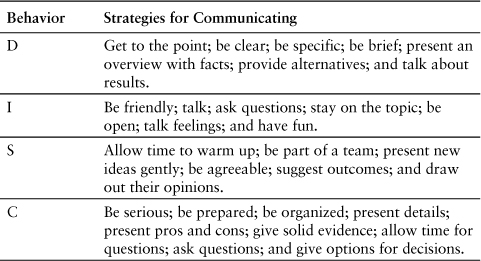

Table 2.1 provides a brief overview of strategies for communicating with others depending on their behavioral profiles.

Table 2.1 Strategies for Communicating

How Do You Take a DISC Assessment?

One of the beauties of DISC is its simplicity. If you get good at it, you can often tell a person’s behavioral profile just by observing body language combined with the way the person communicates. Masters of DISC will often not need assessments at all. However, certain elements of a good DISC provider’s product are not known just by observing and communicating.

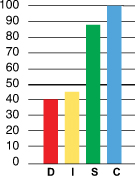

Notice the words, “A good DISC provider’s product.” There are plenty of DISC providers if you Google it. However, they are not all equal. First, you should select one that analyzes and provides information using all behavioral elements and not one that simply provides a DISC graph (see Figure 2.1). To interpret the graph, an individual’s dominant behaviors are depicted by the elements above the bolded midline. For example, in this graph, the individual’s behavioral profile would be a CS. Many companies provide powerful and amazingly accurate reports full of useful information regarding an individual’s behavioral characteristics including sections describing the person, how to or not to communicate with them, and how they will behave under stress.

Finally, it is highly recommended to choose a DISC provider that provides a “wheel,” which is discussed in Chapter 6, “Behavior and Teams.” This is critical because it applies to the dynamics of a team and not just the behaviors of an individual. If you obtain a DISC report without getting a wheel, you are getting only partial benefit.

The Appendix in this book contains a free DISC assessment. Although the free assessment does not produce detailed reports or a wheel, it can get you started by providing your DISC graphs.

Closing

Many would agree that the greatest challenge on software projects is not technology, not the schedule, not requirements, but is people-related. The larger the team, the more potential for conflict. It is well worth the effort at the onset of every project to establish a framework for communication and to provide insight into the behavioral aspects of each of the team members.

It is easy to fall into the trap of organizing a big DISC event where everybody takes their DISC assessment, discusses it, and then puts it on the shelf to gather dust. The true benefit of doing DISC individually and as a team is to incorporate the awareness of DISC into your daily interactions. Accepting others, modifying your communication style, and using the language of DISC are all important. Because teams evolve and some individuals will adapt their behaviors to changing work environments, many teams find it helpful to periodically revisit the DISC.