Chapter 4. Communication

After focusing on team dynamics, the team was behaving a little bit more like an agile team. They were self-managing and respectful of one another’s behavioral styles. Lydia noticed, however, that some of the individuals were better at communicating than others. For example, she noticed that whenever a new idea was brought to Sean, he always initially responded with the words, “Yes, but...” This promoted a negative atmosphere. So Lydia decided to take a step back and discuss some general communication protocols with the team to foster a more productive environment.

Imagine a world without communication. On a typical day, consider how much communication is involved. In just the first few hours of a typical day, think about how many times you either send or receive some form of communication. Did you say “Good morning!” to the people you live with? Did you turn on the TV, open junk mail, read the newspaper, or send an email? We participate in most forms of communication without conscious awareness that we are communicating.

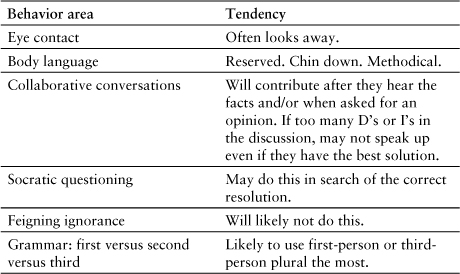

Figure 4.1 depicts Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. According to Maslow, when core physiological needs in the base level are met (food, water, sleep, and so on), most of the remaining needs are fulfilled through some interaction with other people. In other words, communication is a seminal human need. Recall in the fictional movie Castaway, Tom Hank’s character used a volleyball to create an artificial companion to fulfill his insatiable need to communicate.

Figure 4.1 Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Because communication is a core need of healthy people, you’d expect most people to work hard at becoming skillful communicators. In actuality, most people’s communication skills could use significant improvement.

While reading this chapter, keep a conscious eye on your own communication skills and seek out areas for improvement. Adopting just a few of the tips here may help you significantly enhance the interactions you engage in on your project.

Lingo

When speaking or writing, you have many choices regarding language. Consider the following variations of the same statement:

• I want to talk to you about your business requirements.

• I need to talk to you about your business requirements.

• I’d like to talk to you about your business requirements.

• Let’s talk about your business requirements.

• Let’s talk about the business requirements.

• Can I talk to you about your business requirements?

• May I talk to you about your business requirements?

• We need to talk about your business requirements.

• You need to tell me about your business requirements.

Each of these nine statements seeks the same thing, but notice how each makes you feel as you read it. As you read them, imagine yourself as the speaker and then as the listener. Consider which of these puts you more at ease from both sides of the conversation.

As the old adage goes, “It’s not necessarily what you say, but how you say it.” Refined communication skills are the best tools you can have in your tool chest. There are many, many resources on effective communication skills. Most probably offer useful advice, and this book won’t attempt to cover all the best practices of effective communication. Instead, we cover a collection of heavy hitters—those communication practices that tend to be redundantly emphasized in the pop psychology texts.

Whenever an adjective is clunked in front of the word communication, such as good, effective, high impact, and so on, the descriptor is always subjective. The polished presentation by the Cutko knife salesperson to a married couple may dazzle one member of the couple, yet annoy the other.

Therefore, when trying out the communication tips offered in this chapter, try experiencing them from both sides of the table. For example, as with the variations on a theme on the previous page, imagine yourself as the sender and as the receiver of each statement.

Empathy

In the spirit of seeing things from both sides, start with empathy. Empathy is identifying with another’s perspective. Empathy is NOT, however, sympathy.

In the following scenario, Jane, an accountant, is discussing her job with Ron from the software development team:

Jane: My job is stressful at the end of each month. I am required to put in a lot of overtime to close the books. My boss is high strung and is all over me to get my work done. It is annoying—I hate the last week of every month!

Sympathetic Ron: I’m so sorry to hear that. I hate bosses like that—some bosses can be real jerks! What can I do to help reduce your workload and get your boss off your back?

versus

Empathetic Ron: I can imagine what it would be like to work under that type of pressure. A few years ago I had a job with similar circumstances, and I remember what it felt like.

Notice that sympathetic Ron is problem-solving Ron—the fixer. He is like the Mom kissing the child’s boo-boo to make the pain go away.

Empathetic Ron is also understanding and may communicate that he “gets it.” However, he may actually choose not to take sides. He expresses that he can see Jane’s perspective but doesn’t immediately pounce on the problem to fix it, sugar coat it, or pretend it isn’t there.

On a project team, empathy can be a powerful tool. When empathy is genuine, a connection can exist between individuals that enhance their communication with each other. The wall that can exist between people often breaks away when an empathetic connection is made.

During requirements sessions on software projects, there is often an elephant in the room that nobody will discuss: We cannot build everything you have asked us to build. Some of the best-written user stories may never become software because they will be continuously overlooked during sprint planning meetings.

When a feature desired by one or a few is pushed down the priority list, emotions may enter the scene. At times like this, it’s important not to back down and allow emotions to cause low-priority requirements to bloat the scope of a project. At the same time, understanding the perspective of the requirements’ owner can help avoid the loss of commitment from those whose requirements were eliminated. An empathetic viewpoint can do two things:

• It can help validate that the decision to lower the priority of the feature was prudent.

• It can avoid sending mixed signals to those who are disappointed that they won’t get their desired features.

Eye Contact

Many books have been written on body language, and in particular, eye contact. Generally in the Americas and in much of Europe, making eye contact with another indicates that you are listening and interested in what the other person has to say. When you look away, it implies that you are not paying attention, are uninterested, or disagree with what the other person has to say.

Your DISC tendencies may play a role in how you use eye contact. When a disagreeable comment is made to a D (dominator), the D may look at the speaker with a stern, forceful look. The look says, “I hear you, and I do not agree with what you are saying.”

When a C (critical thinker) hears a disagreeable comment, the C may tend to look down or away from the speaker, hoping it will cause the speaker to stop talking.

In the same scenario with an S (supporter), the S is likely to make eye contact with raised eyebrows, exposing negative feelings regarding the comment.

Although those who have a high degree of I (influencer) tend to use eye contact a lot, when listening to another person speak, the I is most likely thinking, “Why is this person speaking? I want to be speaking. How can I capture control of this conversation?”

A lot can be stated nonverbally through effective use of eye contact. A person who maintains eye contact can maintain control of an interaction, especially when the other person looks away.

Overuse or abuse of eye contact could make others uncomfortable, especially if there are possible relationship implications. In some Muslim cultures, for example, eye contact between males and females is frowned upon. In any culture, there is a tipping point between a gaze that indicates sincere interest and a gaze that indicates, “I’m feigning interest.” Eye contact when combined with variations of other facial expressions—raised eyebrows, smile/frown, and so on can take on completely different meanings.

Ambiguity

Ambiguous communication tends to waste enormous amounts of time on a project. When information is expressed accurately, clearly, and without a trace of ambiguity, individuals are best served to interact and solve a problem or make a decision.

When ambiguity is introduced, however, misinterpretations and assumptions are often made, which slow down the productivity of the interaction.

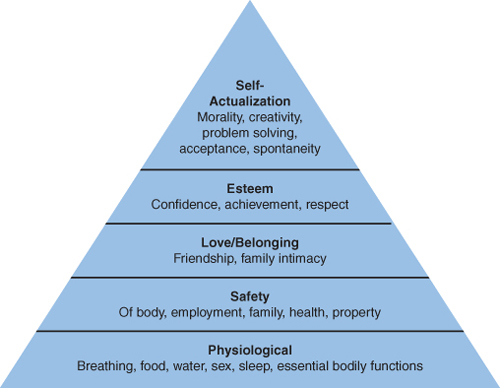

A group of individuals in a meeting room were presented with the following instructions: “Draw a pizza that has eight slices with three lines.” Pen and paper in hand, many of the participants looked puzzled. A couple of folks with inquisitive expressions raised their hands, which caused the facilitator to say, “Let’s see who can solve the puzzle the fastest; then I’ll address your questions.”

This simple puzzle becomes impossible to many who try to solve it because they impose constraints that just aren’t there.

Many will complain that the possible solutions depicted in Figure 4.2 violate the instructions:

Figure 4.2 Pizza Puzzle solutions

Solution A may be disputed by those who imposed an unstated constraint that the pizza can only have three lines. Solution B may be disputed by those required themselves to use only straight lines. In Solution C, each slice has three lines. Most listeners probably inferred that the pizza must have three lines, but the statement could be interpreted as each slice has three lines.

The point of this tricky little exercise isn’t about fooling people; it’s about how even the most straightforward sounding instruction could be interpreted differently by members of a group. When people assume the message was clear, and they impose their own constraints, waste and mistakes can happen.

Body Language

A lot has also been written about body language. Without saying a word, your stance alone can speak volumes. Often, it’s likely that you are not thinking about or feeling what your body is saying that causes others to misread you.

In Shakespeare’s Othello, Othello sensed an uneasiness in the demeanor of his wife Desdemona, which he interpreted as evidence that she had been unfaithful to him. In actuality, Desdemona had been faithful to Othello, and her uneasiness was due to fear that Othello wouldn’t believe her. Othello’s misinterpretation of Desdemona’s nonverbal cues lead to his murdering her.

There is a lot of popular interest in interpretation of nonverbal communication. Television shows such as “Lie to Me” and “Psych” depict characters with acute awareness of nonverbal clues that most people overlook.

Dr. Maureen Sullivan from the University of San Francisco tested 13,000 individuals to assess their ability to detect deception by others. Of the 13,000 people, only 31 could consistently detect deception by others.

Although accurate reading of nonverbal clues is not something everyone can do, most people do tend to interpret nonverbal communication by others, whether it is an accurate interpretation or not. This leads to perceptions that could be wrong.

The focus of this section of the book is therefore not about how to interpret others’ nonverbal cues. Rather, it is how to better manage your own body language to avoid misinterpretation by others. This is called body language self-awareness.

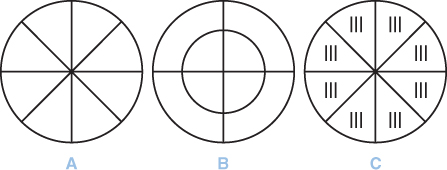

The definitive body language signal is folded arms (as shown in Figure 4.3). When talking to someone whose arms are folded, the popular interpretation is that the arm folder is rejecting or disagreeing with what is being said. In reality, the person could be cold. Perhaps the person is more comfortable with folded arms. It’s not necessarily an indicator of rejection. Unfortunately, actual intent is irrelevant.

Figure 4.3 Body language self-awareness

When Fred is talking to Mary, and Mary’s arms are folded, it’s possible (and even highly probable) that Fred will interpret Mary’s folded arms as rejection of his ideas. The typical observer will look at this situation from Fred’s point of view: “What is Mary telling me?” Let’s try looking at it from the other direction—Mary’s point of view: “Fred is talking to me. I want to fold my arms, but if I do, Fred may think I’m disagreeing with him. It would really be so much more comfortable to fold my arms, but I’m just not going to.”

Mary’s self-awareness of her body language demonstrated empathy toward Fred. Whether or not Mary agreed with what Fred was saying, her conscientious decision to avoid telegraphing negativity offered Fred more freedom to express his thoughts.

The key message here is not that Mary has to agree with Fred. Rather, Mary is empathetic to Fred’s desire to express his ideas freely. The empathetic Mary is more likeable than the (presumed) rejecting Mary, which offers an opportunity for Mary and Fred to have a richer, more engaging interaction on the subject they’re discussing.

Your nonverbal cues may be unconsciously sending a message to others. The characters in Figure 4.4 show an exaggerated expression of nonverbal “shouting.” Without uttering a word, these characters (from left to right) clearly depict arrogance, confidence, and disapproval. See Figure 4.5 for common interpretations of body language.

Figure 4.5 Common interpretations of body language

Cultural Awareness

Nonverbal communication is not necessarily a universal language. The thumbs-up gesture is often used in the United States to indicate agreement and affirmation. The same gesture in Italy means the number one, yet in American Sign Language it means the number 10; and thumbs up in many Middle Eastern countries is considered an obscene, insulting gesture.

Thumbs up is a fairly overt gesture. More subtle is a gentle rocking of the head from side to side, which in many cultures means disagreement. However, the side-to-side gesture in India is seen as a sign of agreement. Misinterpreting this nonverbal cue can often confuse westerners visiting India.

Reflecting Body Language

Echoing the body language of a person you interact with can be interpreted as empathetic. For example, if you talk to someone who leans forward with uncrossed legs and open arms, if you reflect the same pose, you are sending the message: “I am engaged in this interaction, and you have my attention.”

Be prudent when reflecting, though. It could backfire and be interpreted as mocking. It’s also not helpful to reflect a pose that has negative elements. For example, when talking to someone who leans back with arms crossed behind the head, it would be counterproductive to reflect the same negative pose. Instead, you might succeed in drawing the other person more fully into the conversation by leaning forward and engaging eye contact.

Small Talk

Conversations often stray from project-related topics. This is inevitable with even the most focused, driven members of a project team. Discussing the weather, yesterday’s football game, or the price of tea in China may seem to be a waste of time at work. However, this “small talk” can contribute to the communication dynamics of members of the project team.

In the 2009 movie “The Invention of Lying,” characters live in a world in which all thoughts are freely expressed with complete openness and honesty. Nobody tells lies, and nobody withholds information. This leads to unexpected conversations with everyone blurting out what they actually think. These conversations are unlikely in real life, not because all people are liars, but rather because most people tend to withhold thoughts or disguise sensitive and personal interactions with those that are nondescript. This “language” of topics that are mundane and noncontroversial is referred to as small talk.

Most people have a love/hate relationship with small talk. Consider the following interaction. Dave Developer is reluctantly attending the mandatory project kick-off event in the company cafeteria. All members of the project team will be there, along with business executives who will be funding the project (and beneficiaries of the software created by the project).

Barbara Business-Stakeholder had been looking forward to the get-together all week. She was excited about meeting and chatting with all members of the project team. Barbara enjoys things like this—Barbara’s favorite part of her job is talking with people.

Dave, on the other hand, was stressed about the whole thing. What was the point of the social event anyway? A bunch of people standing around jibber-jabbering about meaningless dribble. Dave would go because it was expected, but he was not happy about wasting time talking about things that will not advance the progress of the project.

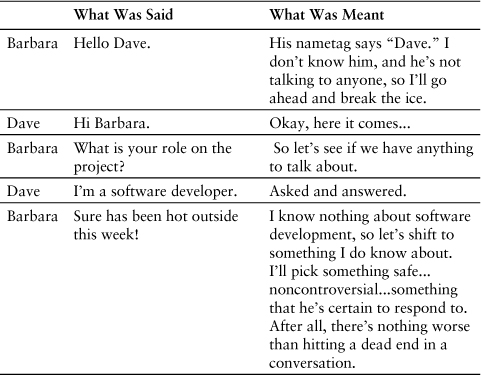

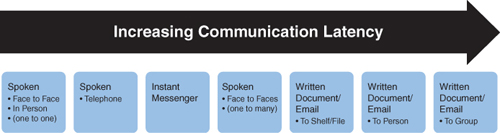

Table 4.1 presents a snippet of a conversation between Dave and Barbara as they meet. The first column indicates what was said (the small talk), and the second column shows what the speaker actually meant (a literal translation of the small talk).

Table 4.1 What Was Said and What Was Meant

Clearly, what had started as a dry small talk session turned into an important meeting for both Dave and Barbara. Agile projects can succeed or fail based on the quality of the communication on the team.

For communication to occur between individuals, some form of a relationship must be formed. If Barbara were to discuss the weather with Frank, the cashier at the grocery store, that relationship may be fleeting. Barbara might have never met Frank before, and she may never see him again. The small talk she strikes up with Frank has no long-term purpose. She is just being friendly in this case.

The small talk that Barbara uses to launch a conversation with Dave Developer, on the other hand, has a more lasting purpose. She is breaking the ice with someone with whom she’ll be working on an important project. It would seem odd to dive directly into rich, intense subject matter. The small talk serves as a warm up that allows a productive working relationship to begin to form.

Collaborative Conversations

If a tree falls in a forest does it make a sound? If something is communicated and nobody hears it or reads it, was it actually communicated? Philosophy aside, from this point forward, assume that at least two parties are required for any form of communication to exist.

The next chapter delves more deeply into collaboration. For now, however, the focus is on collaboration that occurs during a conversation. In oral communication, when speakers and listeners come together, there are increasingly rich levels of collaboration.

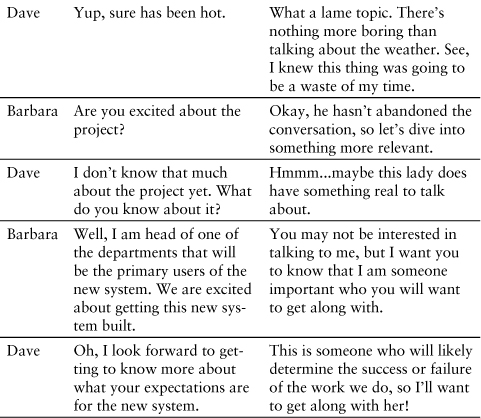

When speakers and listeners are brought together, there must be a match between speaking strategy and listening strategy for a productive interaction to occur. When a mismatch occurs between the level of collaboration desired by speaker and listeners, speakers and listeners tend to get frustrated.

In any given combination of speaker/listeners, the maturity of collaborative communication often aligns with one of the four levels depicted in Figure 4.6:

• Level 1: Speech: A speaker is preaching and/or motivating the listeners, who are often a mixture of passive and active listeners.

• Level 2: Facilitated Discussion: The speaker takes on more of a facilitation role, engaging listeners to contribute to the topic being discussed.

• Level 3: Conversation: At this level, the speaker and listeners engage in a dialogue, where speaker/listener roles are swapped continuously. The originating speaker role may set the tone and direction, after which others involved in the conversation steer its direction.

• Level 4: Collaborative Interaction: At level 4, complete collaboration occurs between members of the group. The speaker/listener roles swap out frequently and swiftly. Members of the group work together toward a common goal (solving a problem, discussing an issue, resolving a need, and so on). At this level, the group takes on its own identity.

Figure 4.6 Collaborative communication levels

Collaborative interaction is a desirable place for a project team to get to and remain at. When a project team reaches this level, members tend to work together to fulfill each other’s communication needs. At this level, communication is leveraged as a tool to advance the progress of a project. When a communication block is reached, other members of the team may step in to ensure that progress is continued.

In improvisational theater, a group of performers work together to create a cohesive (and usually humorous) entertainment piece without a script. Television shows such as Whose Line Is It Anyway? and Curb Your Enthusiasm have showcased improvisational performers. On Curb Your Enthusiasm, a rough sketch of a story idea is presented to the actors, who create the story together in front of rolling cameras rather than reading lines from a script. The pressure of this real-time collaboration draws the best possible work out of each contributor. On Whose Line Is It Anyway? the performers have the added pressure of creating entertaining content in front of a live audience.

One of the greatest challenges of “improv” (as this is commonly called), is the live collaboration that occurs between multiple performers. All members of an improv team know how to capitalize on each other’s strengths and overcome each other’s weaknesses. A goal of an improv troupe is to keep communication flowing with no dead air.

Popular “improv” practices can help foster better communication on teams, such as the following:

• Keep it flowing: Improv masters are skillful at keeping communication flowing, and team members all work together to make the “scene” a success. If one person dominates at the expense of others, the group fails. If one person falters, others will jump in to keep things going.

• Say “Yes, and...”: By responding to a teammate’s contribution with “Yes, and...” you are make a commitment to adding to what has already been offered. This approach maintains cohesion by committing to build upon what was started. It also shifts the burden of enhancing the overall contribution.

Mary I believe customers will want a user interface that is attractive and is easy to use.

Fred Yes, and...

After the “and,” Fred adds new information. The person who says, “Yes, and...” is expected to contribute new content, not just restate or transform what was already said.

Fred Yes, and the screen should be clean with few widgets, options, and displayed content.

Jane Yes, and the system should be fast, too. New windows should pop up within just a second or two from the time they are requested.

David Yes, and... [Continues until the group runs out of steam.]

• Avoid blocking: Blocking is the opposite of “Yes, and...” Expressing a negative reaction to the previous contribution can stop the conversation flow dead in its tracks. It may be simply saying, “No,” or it could be ignoring the conversation and shifting to a completely different subject. A high D (dominator) is likely to block when in disagreement with an idea that is being cultivated.

Mary I believe customers will want a user interface that is attractive and easy to use.

Pat No, actually customers will want a feature-rich application with a lot of information and user-configurable capabilities.

OR

Pat I’m not that concerned about the user interface; it’s the speed of the application that I’m worried about.

• Avoid questions: Asking questions could be perceived as a “punt,” which shifts the burden to someone else. This is a common tactic of a high C (critical thinker), who may believe that critical questions are contributing to the team. Rather, they demonstrate that the questioner doesn’t want to play the game and is quick to shift the “hot potato” to someone else.

Mary I believe customers will want a user interface that is attractive and is easy to use.

Derek Are you familiar with the corporate user interface style guide and the standard UI templates?

OR

Derek How do you define “easy to use?”

Notice how Derek’s questions push the burden immediately back to Mary. This places responsibility on Mary to keep the conversation flowing, and Derek plays a minor role in the overall results of the group, even though Derek probably feels that his inquisitive style is helping.

• Include other team members: Help draw in other team members who are not contributing by providing information they can build on. This requires an awareness of skills and interests of those team members. Notice the collaborative helpful tone of Mary and David’s exchange:

Mary I believe customers will want a user interface that is attractive and is easy to use. David, I remember that the user interfaces you developed on other projects were well accepted by your users. How can we achieve the same success on this project?

David Well, I should conduct a focus group with key target users. Also Derek is a pro at screen layouts. We’ll want to get him involved.

• Be Socratic: The great teacher and philosopher Socrates devised a teaching technique that broke from the conventions of his time. Rather than blurt knowledge, he posed a series of questions to his students. This allowed the students to navigate their own path of understanding and learning. These questions allow a speaker to clarify and qualify what is being said.

Note that asking questions is a “no no” in the improv world because it is seen as deflecting involvement. A Socratic series of questions, however, encourages active involvement by the questioner. As a facilitation technique, it can keep people on task and help them avoid getting off track from the goals of the communication session. With this technique, the facilitator is not questioning what is being said. Rather, the facilitator is asking questions to encourage the speaker to elaborate, enhance, and clarify what is being said.

Examples of helpful Socratic questions:

• What makes you say that?

• Can you describe an example of what you’re talking about?

• How does this align with what others have been saying?

• How does this differ from what others have been saying?

• Are there other ways to ask what you are asking?

And a few metaquestions (questions about the question itself):

• Did the way you worded the question get the response you expected?

• Is that a good question to be asking?

• Why is what you are saying important to the project?

• Be even more Socratic: Another technique often attributed to Socrates is to feign ignorance—to pretend to have no knowledge of something you are fully knowledgeable about. Listen in on the following conversation:

Fred Would you like me to explain the steps involved in underwriting an insurance policy?

Jane [Having spent the past 20 years as an insurance underwriter and holding various certifications as a certified underwriter, bites her tongue, feigns curiosity and interest, and says...] Yes, please tell us about it.

Feigning ignorance can be difficult for those who are knowledgeable on a subject. Their egos entice them to let everyone know how smart they are. By swallowing pride and feigning ignorance, though, there is a great opportunity to augment their knowledge with another’s perspective.

In the preceding scenario, if Jane had not allowed Fred to continue, she might have lost the opportunity to either validate what she knows or add to her knowledge of the subject.

The Power of Shutting Up

When used properly, silence can be a powerful communication tool. Proper use of silence includes appropriate choice of supporting eye contact and other body language.

In this scenario, Fred is undecided about whether to include a certain feature in the scope of the system. Jane (who is likely a high D and/or a high I) feels that it’s necessary to say something:

Fred I can’t quite decide whether that feature is important and should be included in the scope of the system.

Jane I think it’s quite important. I’d include it if I were you.

OR

Okay, what can I do to help you decide?

When will you decide?

If instead Jane had said nothing, she could have urged Fred to come to a decision. If Jane looked Fred in the eyes and leaned forward, she would silently be saying, “Take your time, Fred, I’ll wait for you to think about it and come to a decision.”

If Fred happens to be a high C, he is unlikely to make a snap decision and will want time to think about the implications of his decision before announcing it. By exercising restraint and using silence with appropriate body language, Jane allowed Fred to make a more informed, well-thought-out decision.

Using silence as a tool can be difficult for high D’s and high I’s. Silence can drive these people nutty, and they’ll likely try to fill it with sound.

Communication Latency

In 1860, a message crossed the United States from coast to coast in ten days via Pony Express. Today, it’s possible for an email message to make the same journey in less than a second.

This doesn’t mean, however, that email is the definitive communication speed test benchmark. Email has its place but does not guarantee efficiency or speed. You probably have messages in your email inbox from more than ten days ago that were overlooked or not read. If, however, someone rode up alongside you on a horse and handed you a letter that had been in transit for the past ten days, there’s a good chance that you’d drop whatever you’re doing to read it.

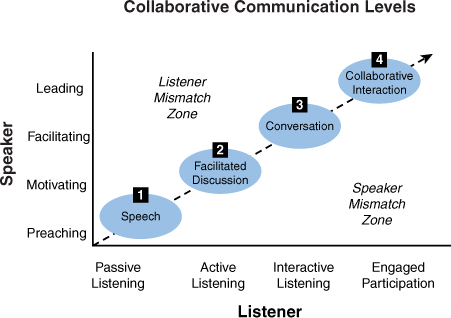

Communication latency refers to the delay that occurs from the time something is communicated until the time it is received and processed. A common goal of an agile project is to reduce communication latency. Real-time interactions can keep a project moving forward, whereas delays can have a compounding detrimental impact to the project. Figure 4.7 depicts commonly used communication tactics, shown with increasing amounts of latency (or delay) from when the sender sends the message and the recipient receives the message.

Figure 4.7 Increasing communication latency

As an example, receiving the message does not mean that it arrived in the recipient’s inbox. The communication transaction is complete when the recipient reads and understands what was communicated. It’s ironic that some of the more popular modern tactics actually introduce the most latency.

The more time that passes from the sending of information and the processing of that information, the greater the risk the information will be misunderstood, ignored, or misused. Notably, the context that was in existence at the time something is communicated will likely have changed as more time passes. This causes information to be processed out of context, which can lead to misinterpretation.

Ideally, all project communication would occur live and in real time. Behaviorally, real-time conversations are fun and desirable for a high I (influencer); at the same time they can be exhausting and undesirable to a high C (critical thinker). When Mary asks Derek to do some research on a certain business requirement and to let her know what he finds out, his follow-up actions will depend on his behavioral tendencies.

Because Derek is a high DI, he may likely do a cursory job of researching (or try to delegate it) and will report what he learns back to Mary in person. Derek is likely to report back to Mary within hours so he can get the to-do item off his list.

When Derek tells Mary what he has learned, he will consider his task complete. If Mary were to ask Derek to write up what he discussed, Derek is likely to be frustrated or annoyed.

If Mary had asked Carl instead, she would have experienced a different response because Carl is a high C. Carl is likely to take his time doing a thorough job of researching the problem. When he has researched to his satisfaction, he will likely write up the information and send it to Mary in an email message. It’s highly unlikely that Carl will call Mary or see her in person to discuss what he learned. After Carl clicked “send” he considered his task complete. If the email server crashed and the message never made it to Mary, Carl would likely have never pursued making sure Mary received and understood the information.

The contrast between Derek’s and Carl’s behavior is important. Carl probably did a much more thorough and accurate job of addressing Mary’s needs. However, the delay in getting the information to Mary could have potentially caused other delays. Additionally, if Mary never received (or noticed) the reply, Carl’s work was pointless.

On the other hand, Derek handled the request in a timely manner, but the quality of his research was probably much poorer than what Carl produced.

In either case, it’s productive for all team members to maintain awareness of communication latency and to work to minimize delays in communication threads.

We the People...

Here’s a quick grammar lesson:

• First-person singular: “I...”

• Second-person singular: “You...” Third-person singular: “He/she...”

• First-person plural: “We...” Second-person plural: “You...”

• Third-person plural: “They...”

Regardless of your intent, when you choose to speak in first-person versus third-person, and singular versus plural, others’ perception of you will likely be affected by what they hear. Generally:

• Those who use first-person singular can be perceived as arrogant and boring. Others’ eyes may glaze over as you continually say, “I this,” and “I that.” That doesn’t mean you mustn’t ever talk about yourself. However, it’s a good idea to monitor your “me” speak and be cognoscente of a lack of empathy for your listeners.

• Those who use second-person can be perceived as nagging or preaching. Listeners tend to get defensive and raise their guard when they hear, “You this,” and “You that.” The “You” speaker may also be seen as arrogant, which is often a turn off to listeners.

• Those who frequently speak in the third-person may be viewed as gossips. When you choose to talk about others, be aware that any hint of judgment or criticism could cause you to be labeled as a critic and a gossip. People may be less inclined to be open with you to avoid being judged or criticized by you.

• The use of first-person plural is a great way to get collective buy-in for whatever you have to say. When you say “we,” others see you as part of the team, a member of the family, someone who has the same skin in the game that they do. Not only can this tactic help you avoid alienation, it can encourage others to be more open with you.

Closing

The following tables summarize key contents of this chapter from the DISC behavioral perspective:

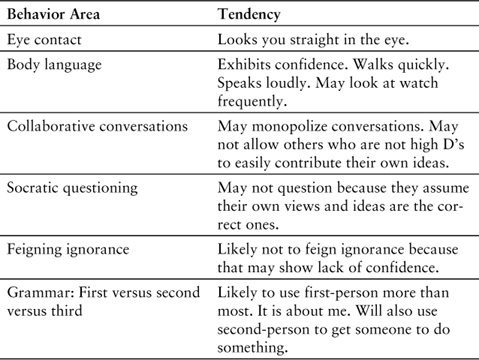

Table 4.2 A High D (Dominator) Likely Exhibits These Tendencies

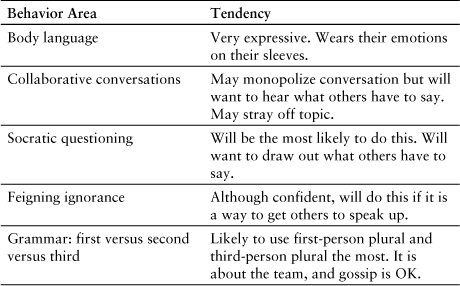

Table 4.3 A High I(Influencer) Likely Exhibits These Tendencies

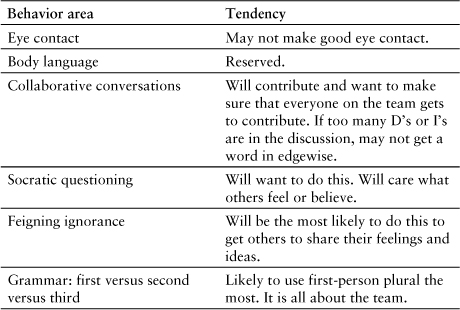

Table 4.4 A High S (Supporter) Likely Exhibits These Tendencies

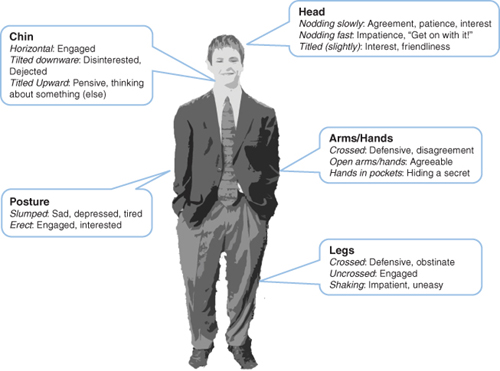

Table 4.5 A High C (Critical Thinker) Likely Exhibits These Tendencies