Chapter 6. Behavior and Teams

Now that Lydia got the team to start understanding each other’s behaviors and to modify communication styles to work more effectively as a team, the group needed a tool to easily visualize and understand the team dynamics as a whole. The team was ready to learn about and apply lessons learned from “the wheel.”

Harmony/Conflict

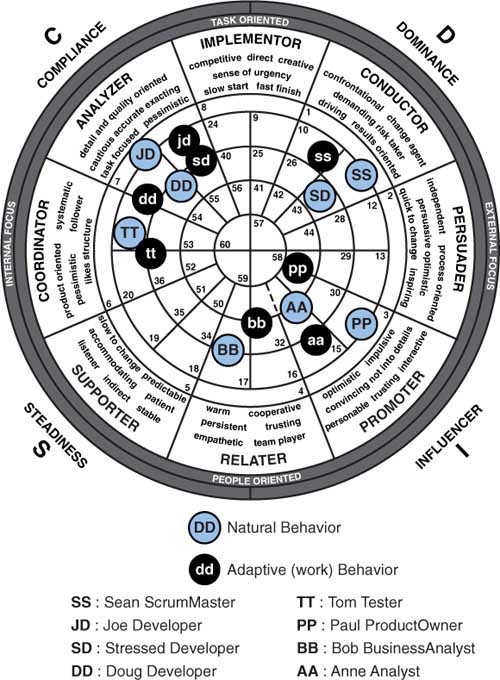

Chapter 2, “Behavior and Individuals,” discussed DISC to understand and accept individuals and to achieve greater communication on a one-on-one basis. This chapter builds on this core understanding and expands it to a team level. The “wheel” plots an entire team on a spatially accurate circle. Although several wheels exist, Figure 6.1 shows an example of a wheel provided by The Abelson Group.

Figure 6.1 Team Wheel (The Abelson DISC Behaviors Wheel is an adaptation of the Target Training International, LTD. Wheel and is a trademark of The Abelson Group™)

The wheel is a simple, yet extremely powerful tool applicable to any agile team. The wheel is a true geometric figure; the closer team members are located to each other spatially, the closer their behaviors. The team can visually see how well team members will get along and where to be prepared for natural conflict. Conflict is magnified if some team members have not been trained in DISC.

Based on the location of Joe Developer and Doug Developer in the wheel depicted in Figure 6.1, they should get along extremely well like two peas in a pod. Paul Product Owner and Joe Developer, however, will have a tendency to conflict.

An exercise that could be conducted in a training class is to have students write down the names of three individuals with whom they enjoy their company. Then list three persons that they might detest or not want to hang out with. The three enjoyable individuals typically have similar DISC profiles, and the three detested ones typically have polar opposite profiles (that is, are furthest away from them in the wheel). Many believe this is because people tend to like people who are like themselves. Two I’s (influencers) will have lots of conversation; two S’s (supporters) may be best friends; two C’s (critical thinkers) will thrive on details within the team; but what about two D’s (dominators)?

The following is another true story regarding a leader of a consulting company in Dallas. The company wanted someone to move out to Denver to help start a new office. Denver, the mountains, skiing, cooler weather...how could anyone pass that up? It was almost a dream come true when three Principal Consultants volunteered to join the leader and move to Denver to help the start-up office. Principal-level consultants were few and far between because they had a unique combination of the strongest technical skills combined with outstanding communication ability and business acumen to lead teams and help land new business. This supposed dream turned out to be a nightmare.

As you probably expected, these three Principal Consultants were extremely high D’s. Because high D’s are tremendously competitive, they all strived to be the top dog and the “right-hand man” of the leader of this small, new office. The leader wound up literally facilitating a discussion to help them try to understand and accept each other. He discussed how each was more than capable and had their unique strengths and weaknesses. And he then went on to explain that none of them had to be the top dog because they were a team. Although he never completely solved the problem, the discussion avoided what would have probably resulted in fist fights.

Why Not Hire a Team with Members That Will All Naturally Get Along?

Wouldn’t it be best to just hire a team of all C’s, all S’s or all I’s so that everyone would just get along. Unfortunately, that seemingly simple solution simply will not work.

What would happen if you hired a team of all C’s? On the positive side, all work would be done with high quality and perfection. On the negative side, however, things would tend to take longer. No one would be naturally driving the project to completion. You may have achieved the prefect product if the project did not get canceled by stakeholders concerned that it was taking too long and costing too much money.

So the best teams comprise a blend of behavioral profiles. You want team members to consist of a combination of D’s who will make quicker decisions and help drive the project; C’s who will focus on the details as they analyze requirements, test, and write code; S’s who will bring harmony to the team; and I’s who will keep the communication going, optimism high, and energy flowing. It is healthy to have some team members optimistically viewing the project in a “glass is half full” perspective while others are continually concerned about the project’s status or level of quality. Therefore the best teams have a mix of behavioral profiles that in turn tends to also result in natural conflict.

Be Prepared for Conflict

The beauty of the wheel is that it immediately visually shows team members where this natural conflict will occur. This is especially important with new teams who have not yet gotten to know one another and who have not gone through the forming, storming, norming, and performing stages as described in Chapter 3, “Team Dynamics.”

The more individuals’ locations on the wheel is to the outside of the wheel, the more intense their behaviors. So a D on the outskirts of the wheel will tend to be extremely outspoken and driven. She could likely appear to someone who is on the opposite side of the wheel as being arrogant, opinionated, or even rude. A D who is closer to the middle of the wheel will have tendencies to speak up and drive the project, but these behaviors will not appear as intense to others.

Team members can understand and accept one another and know how to best communicate with one another by looking at the wheel. Similarly, they can be prepared for conflict. For example, an I and a C will naturally conflict or at a minimum will naturally annoy one another. The C will want data, whereas the I says “trust me.” Similarly, a D will want quick answers, whereas a C will tend to overanalyze (to the D’s perspective anyway).

Stressed Out

Will individuals behave differently under stress? That depends. The wheel shows each individual’s natural behavior (see the initials in the figure that are uppercase) and their adapted behavior (see the lowercase initials).

You can see that in most cases in the preceding example, the team members’ natural and adaptive behaviors are similar. Look closely at Stressed Developer (SD). His natural behavioral profile is a D, but his adaptive behavior is a C. That is, to successfully be a developer in this organization, he has adapted his behavior to that of a C. However, under stress his natural behavior will be revealed.

Team members who naturally seem to get along may all of a sudden become conflicted when the project falls behind schedule and the team feels pressured or when some stakeholder indicates she was not happy with the results of a sprint. Stressed Developer will revert to his natural behavioral tendencies and will start to drive things and be a little more outspoken than he used to be. Without knowledge gained from the wheel, team members may get caught off guard, resulting in clashes and even greater stress on the team.

By viewing the wheel in advance of stressful situations that occur from time to time on projects, the team can be prepared for different behaviors that will surface under stress or pressure.

Fill the Gaps

Another important item that can be gleaned from observing the wheel is gaps on teams. For example, envision a team’s wheel displaying no individuals in the D segment of the circle. The team would most likely lack a drive for closure, take longer to make decisions, and have less of a sense of urgency. In this situation, either someone needs to take the role of a D when working on the project, or the team should hire a D. Either way works; however, a team member acting in a role outside of his normal behavioral style may become overly stressed as he works harder trying to behave in a way that conflicts with his natural style.

Organizational or Team Culture

Teams and sometimes entire organizations share a common culture. For example, a large biotech company employed mostly scientists. Even the leaders of the organization were once hands-on scientists. As you might imagine, most individuals at this company were high C’s. In general, the company made slow decisions, the employees were low-key and detail-oriented and did not like change.

In another example, at a large finance company, the culture was fast-paced, voicing conflicting opinions was encouraged, and there was frequent change. This company’s culture was that of a D.

By observing the wheel of a team or the wheels of many teams within a company, you can depict what the culture will be and gain significant insight on how the team and/or organization will behave.

Closing

The best teams have a blend of behavioral profiles, which also means that the best teams will be up against natural human conflict. Understanding the DISC as a general framework is one step in helping to minimize conflicts. Visually seeing who on the team will likely conflict with whom will best prepare everyone. Doing this at the onset of a project is critical. After conflict occurs and relationships potentially are destroyed, it is too late.