Chapter 15. Change Exercise

This workshop corresponds with Chapter 7, “Change.”

Change can be difficult for some people to talk about or to even think about. Addressing need for change head-on can be fruitful and is an essential prerequisite to making change happen. This exercise is designed to soften the severity of discussions about change through the use of a fun and lively game. The fast-paced nature of the exercise avoids arduous emotionally charged discussions about change. Rather, it facilitates quick brainstorming about things that need to be changed without stewing over the challenges or consequences—almost like pulling off a bandage in one quick swipe.

Overview

The room is split into small groups that will be competing against each other. Each team will sit in front of a flip chart or white board while one member of each team is drawing a picture of a desired change. The facilitator shows a card containing a description of a desired change on it to the designated drawer on each team. Each team should guess what is being drawn by shouting out the answer. Drawing responsibility rotates on each team so that everyone serves as drawer and guesser. The first team to guess correctly earns a point. At the end of the game, the team with the most points wins.

Setup

The materials required are simple:

• Blank 3×5 cards

• Pens

Prior to beginning the game, hand out stacks of 3×5 cards and ask all participants to grab a card and draw a vertical line down the middle of it, dividing it into two sections. Label the left side “Now” and the right side “Goal” (see Figure 15.1). Next, on the left half of the card, write a phrase or a single sentence describing something that is undesirable now. On the right side, write a phrase or single sentence describing a corresponding positive goal. When writing the goal, consider the changes that will need to occur in order to attain the stated goal. Give five minutes to fill out as many cards as possible. Ask the participants to work individually and not share or discuss the information on their cards. Tell them that others will be reading their cards, so be helpful by writing or printing as neatly as possible. Have the participants write their names on the back of their index cards.

Figure 15.1 The card should look like this.

Collect all the cards and mix them up for use during the next part of the exercise.

Examples include the following:

Now: The project requires skills we don’t have on the team.

Goal: Training is provided for everyone needing new skills.

Now: Each team member is expected to juggle multiple projects at once.

Goal: 100% dedicated resources on the project.

Now: Daily standup meetings take too long.

Goal: Everyone follows the Scrum meeting format in the daily meetings.

The Drawing Board

Decide how many teams will compete and designate a space for each team to work. Remember that the facilitator will observe all the teams during the game to listen for a winning answer, so try to position the teams where the facilitator can see and hear each team. The overlapping chaos contributes to the high-energy fun of this game. Because all teams are solving the same “puzzle” simultaneously, some individuals may eavesdrop on what the other teams are doing. In the spirit of the purpose of the game (open communication) there’s no need to be concerned when this happens.

The Teams

Divide up the room with approximately the same number of people on each team. There are no specialized skills required for this game, so there’s no benefit in trying to “even up” the teams in any manner other than head count. If the teams don’t have the same number of people, it will not affect the outcome of the game. The goal is to ensure that everyone has a chance to participate as a drawer and as a guesser.

Facilitation

For each round, the facilitator picks a card off the pile and reads the name on the back of the card. This person comes up to the front of the room and helps the facilitator monitor this round.

Have each team select one person to be the drawer for the round. Make sure the drawer has a pen and is standing in front of the drawing board before the game begins.

Give the following instructions to all participants:

“Shortly I will be showing one of the change cards to each of the drawers. When I say ‘Go!’ the drawer should draw the desired change. After you read the card, focus on the section labeled ‘Goal’ and draw a picture representing that change. You may not use words, letters, or numbers, and you may not speak while drawing.”

Typically, most participants are not going to be skilled artists. If any of the players happen to have artistic talent, the game moves so fast that there is little time to create a masterpiece. Master doodlers, on the other hand, may find the game easier than others. Some things are easier to draw than others, and lack of artistic talent can generate a lot of laughter!

For example, when reading a card containing the goal, “Training is provided for everyone needing new skills,” one drawer might try to show some depiction of a classroom or a teacher. Another might draw a metaphor or even a homonym (such as picture of a train).

“As you draw, your teammates will try to guess the change that you are drawing. Listen closely to the guesses, and when you hear the correct answer, point to the person who made the guess. The facilitator will ask the player to repeat the answer and judge whether it is correct. If the answer is correct, it scores a point for that team, and the round is over.”

Because of the possible complexity of each described change, it’s rare that anyone’s guess precisely matches what’s on the card. The person who wrote the original card will judge whether a team’s guess is close enough to count as correct.

When someone makes a correct guess, a point is earned for that team, and the round ends. The facilitator should determine how to end the game. Often, a time limit or a specified number of rounds is used. When the end of the game has been reached, the team with the most points wins!

Post-Exercise Discussion

After the game concludes, it’s important to have a discussion about the change goals. The facilitator should be prepared to delicately handle changes that cause discomfort for some. Additionally, there may be disagreements that require some mediation.

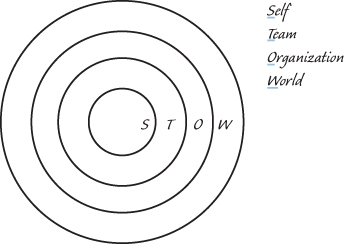

A structured way to facilitate the post-game discussion is to use the S-T-O-W technique. On a white board or flip chart, draw a target with four rings. Mark the center “S”; then mark each subsequent ring with “T,” “O,” and “W.” Write a legend next to the target showing Self, Team, Organization, and World (see Figure 15.2). This target will be used to specify the subject of each change.

Next, retrieve the first change card from the game. Write “1.” followed by the change goal from the card. Ask the participants where this change belongs in the target and write the number in the corresponding ring on the target.

For example, some may feel that “100% dedicated resources assigned to the project” may fall in the “Team” ring, whereas others believe it belongs in the “Organization” ring. This offers an opportunity to discuss where and who can make this change happen. You might discuss that if the team is not empowered to change how individuals are assigned to projects, the change should likely be escalated to the organization level. This approach can center the discussion on how to get to decision makers in the organization that have the authority to make the change happen.

During discussions about changes to the organization, be prepared for statements such as “It’ll never change; it’s been that way forever,” or “Nobody knows why we do things this way; we just do.” Recently, in a presentation about agile software development to 100 executives at a major corporation, one of the executives interrupted the presentation with the comment, “This agile stuff makes sense, but it will never work here. Our organization would never permit such a radical change to the way we run projects.” Another executive in the room piped in, “What are you talking about? We are the organization. We are the reason we do things the way we do. If we are ever going to change, it has to start here, with us.” It’s funny how many people can refer to an organization as an abstraction, as though they are not the organization. Recognition of the presence of individuals in an organization who wield decision-making ability is an important step in accommodating changes in organizations.

For change items assigned to the “Self” ring, the discussion will be quite different—centered on how to encourage individuals on the team to change. Be cautious during these discussions. Talking about how to change an abstraction (the organization) or change other individuals is vastly different than discussing changes to one’s self. Also be cautious to avoid directed criticism. If John says, “Mary needs to avoid discussing irrelevant details during the standup meeting,” Mary may feel cornered, vulnerable, and uncomfortable. Try generalizing “self” changes so that they could potentially apply to any or all individuals on the team.

On an agile team, changes to “Team” offer a great opportunity that could be resolved during the exercise. The lightweight organizational structure of a team on an agile project provides the leverage needed to efficiently introduce change. If the team decides to change the way standup meetings are held or how work is assigned, it shouldn’t require any bureaucracy. It ought to make a decision together and move forward.

Changes to “World” may seem unnecessary because it’s beyond the power of a group to change the world. However, identification and discussion of items that influence us and that we cannot change can be helpful. Working around (and despite) immutable things is a necessary element of how a healthy team works productively together.