6 Café Helena

Not Your Average Cup of Coffee

María Fernanda Trigo

Coffee was Maria Helena Monteiro’s passion. Although she lacked the expertise to run a plantation and market the product, she risked her family’s savings and lived far from her husband and daughters to pursue her dream. She learned the growing and roasting techniques, the best ways to organize and lead her employees, and how to differentiate the product. She is one of a handful of female Brazilian coffee entrepreneurs.

In 1999 Maria Helena Monteiro decided to follow her dream and become an entrepreneur, even though this meant living 4 hours away by car from her husband and daughters. She was committed to cultivating her dream in a traditionally male-dominated industry, coffee growing. Her native Brazil is the world’s largest producer, with a long and proud history of coffee growing, roasting, and exporting.

The coffee business was not new to Maria Helena. She grew up on her grandfather’s country estate during the military dictatorship of the 1960s and early 1970s. She studied at the College of Social Sciences at the State University of São Paulo (UNESP) in the city of Araraquara, where she met her future husband. They moved to São Paulo in 1974, and she embarked on her career as a professor. A year later she joined a multinational human resources firm, where she had a stellar career, starting as a recruiter and work ing her way up to partner. Her tenure included a 9-year-long assignment in Rio de Janeiro. She left the firm in 1998.

Maria Helena remembers wanting to own Monte Alto, her grandfather’s estate, from an early age because of her emotional attachment to the land. Monte Alto had produced coffee until the early 1950s. Growing up there, Maria Helena saw her grandfather become a prominent coffee exporter. In time, Monte Alto stopped producing coffee and switched to growing cotton and other crops. Later, Maria Helena’s grandfather divided the land among his children and grandchildren.

Maria Helena began by buying her father’s share. He gladly sold it to her because he no longer had the financial resources needed to work the land, which had been degraded by continuous cultivation. She then purchased the rest of the land from family members with the savings she and her husband had accumulated during their careers. Today the estate encompasses 242 hectares, most of which are devoted to cultivating coffee, while a small part still functions as a farm.

After acquiring the land, Maria Helena was ready to pursue her dream, “to revive the old and forgotten coffee tradition in the region.”1 While she grew up surrounded by coffee leaves, she was not well versed in agri business. She encountered a general lack of support among the coffee experts she contacted and was derided by those in the industry for being a novice. As she recalls, “Criticism filled the streets of the town with the general belief being that I was wasting my family resources in an industry that formed part of the past of the region, not the future.”2

Monte Alto is in the municipality of Dourado, located in the state of São Paulo, 270 kilometers from the capital, between the cities of São Carlos, Jaú, Araraquara, and Brotas.3 The town was founded around 1880 and became known as the Heart City because of its heightened importance in the coffee industry during the 1890s. By the time it had attained political independence in 1897, electricity, paved roads, potable water, and the railroad had all come to the town.4 When coffee prices plummeted in the wake of the 1929 crash, all the plantations in the region switched from growing coffee to planting more profitable crops such as cotton and corn.5

Early Challenges

Despite her lack of agricultural experience, Maria Helena enthusiastically embraced the tasks of managing the planting, farming, collecting, processing, distribution, and commercialization of coffee. She had few reference points to follow in the region, as it no longer produced this product. She hired technical advisors and struggled to find an administrator who could run the entire operation for her. However, her first lesson, she says, was to recognize that things worked better when she was present. Thus, she decided, with her family’s support, to leave the city and move 4 hours away to administer the business on the estate before her money ran out and her dream vanished. She dismissed the administrator and the agronomist she had hired and spent the next 4 months immersed in reading about coffee and learning when and how to plant and collect and how to grade and sort the beans. She recalls,

With total dedication I began conquering my space and learning more each day. . . . I grew accustomed to being out in the sun, in the rough style of the rural people, to live without my family, my daughters, who many times phoned because they needed something. . . . I would finish the conversation with my heart in my hands.

Ultimately, her venture would not have succeeded without her being on site and involved with everything. She advises, “Be always present, participating in every activity, overseeing everything that has been established. . . . It is necessary to be dedicated, persistent, and committed to your objectives.” She adds that “a key factor is to ensure the buy-in of the professionals and employees involved in the business.”6

Maria Helena’s next challenge was to gain the respect and commitment of the workers. Because the region’s agriculture was focused on other crops, it was difficult for her to hire experienced workers to plant, grow, and collect the coffee grains. The few she could find were startled to see a woman running the business, especially one with little knowledge about growing coffee. Suppliers were also hard to come by because most doubted the sustainability of her coffee plantation. Maria Helena explains that most rural people preferred to work on orange farms, the new predominant crop in the region.

To overcome these challenges and to become more attuned to her laborers’ needs, Maria Helena sought help from the rural workers’ union. Then she personally trained the workers on how to collect the coffee grains as a way of motivating them and gaining their commitment. She remembers using a great deal of dialogue, attention, and care. Over time her efforts paid off, as new workers began showing up on their own. She admits it took at least 3 years before she finally felt more secure and knowledgeable about the coffee industry.

Growing Pains

A turning point for Maria Helena’s aspirations came with her first harvest. Coffee prices had fallen on the world market, causing her to rethink her strategy and seek an alternative way to add value to her product if she were to recover her steep investment in the land. She took her inspiration from the fact that, while Brazil is both the largest coffee producer and one of the largest consumer markets, the majority of Brazilians do not drink high-quality coffee. In fact, the consultancy Euromonitor International found that most coffee drinkers in Brazil consume standard and economy brands because of a widely held belief that all coffee types are essentially the same, a perception that resulted from the popularization of the product.7

According to a report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture, Brazil sometimes accounts for about a third of the world’s coffee output.8 The majority of Brazilian exports are green beans, which are a commodity. Therefore, their large volume generates little value. As Maria Helena explains, green coffee grains are usually sold to international roasting companies, which then process and mix them with other grains and market the final product under their own brands at higher prices. For instance, while traditional green grains sold in 2005 for US$50 for a 60-kilogram sack, gourmet coffee sold for up to US$245 a sack.9

In 1999 the Brazilian Specialty Coffee Association (BSCA), with the support of the Ministry of Agriculture, began to promote the production of high-quality coffee through contests and other types of programs.10 Recently, the Brazilian Coffee Industry Association (ABIC) launched two new initiatives—the Sustainable Coffee in Brazil Program and the Quality Coffee Circle Program—aimed at increasing coffee consumption and promoting the production of fine and gourmet coffees in the country.11 Because gourmet coffees are up to twice as expensive as standard brands, sales of these products are marketed to higher-income consumers.12

There are two major coffee varieties in the global market: arabica and robusta. Arabica beans are used primarily in the production of gourmet coffee. This variety originated in Arabia, as its name suggests. It grows better in mineral-rich dirt at high elevations and produces a full-bodied and full-flavored coffee with a rather low caffeine content.13 Differentiation in taste is achieved through different crop varieties. In contrast, robusta beans grow quickly at low elevations, have double the caffeine content of arabica beans, and, if overproduced, can have a bitter taste.14

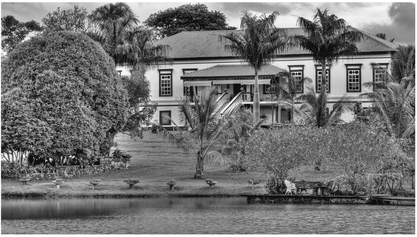

Maria Helena’s Monte Alto estate (Figure 6.1) is well-suited for growing arabica beans. The plantation is at an altitude of 705–732 meters. During the summer, the temperatures range from 18ºC at night to 30ºC during the day (64–86ºF). In winter, they range from 6ºC at night to 20ºC during the day (43–68ºF). The region also enjoys plentiful rain, which eliminates the need for irrigation systems. In addition, four lakes surround the estate, providing even more natural sources of water that form into streams. Finally, the terrain is rich in red dirt.

Deciding to focus on gourmet coffee because she did not want to simply produce a commodity without any added value, Maria Helena opted to produce four varieties of high-quality coffee from 100 percent arabica beans: Red Catuaí, Yellow Catuaí, Acaiá, and Obatã. She makes three blends with arabica beans and two blends with coffee cherry exclusively.

Coffee cherry refers to the coffee seed that forms the pit of a coffee cherry. The cherries are collected when they are ripe and bright red in color.15 The pulp and mucus are removed, and the seeds are either set to dry or sent to a fermentation tank. They are then sorted by density—the greater the density, the better the quality.16

As Maria Helena explains, gourmet coffee is appraised and classified in a way akin to wine, mostly on the basis of body, flavor, bitterness, and sweetness. Good marketing, promotion, and distribution can fetch much higher prices.

Using one of the coffee cherry blends, Maria Helena developed her own brand: Café Helena. She gave it her name and added to the logo the year 1813, when the plantation was originally founded. Thus, Monte Alto plantation first began by just growing and harvesting and then added roasting, grinding, and packaging under Maria Helena’s leadership. She invested close to BRL3 million (US$1.4 million) to equip the plantation for the roasting, grinding, and packaging processes.17 The bulk of her output is exported by a third party. She also sells her branded coffee through distributors around São Paulo. In addition, she has developed a website (www.cafehelena.com.br) with an eye to selling her coffee online.

Maria Helena faces intense competition, as Brazil’s coffee industry is very fragmented and regionalized. According to Euromonitor International, in 2007 there were 1,229 coffee companies and 2,512 brands in Brazil. About half these companies are located in the southeastern states of Minas Gerais and São Paulo.18 According to the Coffee Industry Union of the state of São Paulo, in 2005 the state accounted for 43 percent of ground and roasted coffee—approximately 40 million coffee sacks.19 The three leading multinational players—Sara Lee, Melina, and Nestlé—together had a 28 percent share of the retail volume in the Brazilian market in 2008.20 The Pilão brand, from Sara Lee, leads in retail volume and value according to 2008 data. In addition, a survey conducted by the Qualibest Institute reported that this brand has the highest consumer awareness.21

The Market for Quality Coffee

Maria Helena’s decision to focus on gourmet coffee dovetails with the general trend in the market. Consolidation among the leading players has driven smaller domestic competitors to invest in fine and gourmet coffees to sustain profitability. High value-added coffee has enormous growth potential in Brazil because there is no dominant gourmet brand on the market.22 Maria Helena has organized several meetings to attract more coffee growers to produce gourmet coffee. Her efforts have contributed to an increase in the number of specialty coffee producers in her region— from six to eleven.23 In the future, she would like to see the formation of a “Coffee Club” to recognize the central part of São Paulo as a region that produces high-quality coffee.

Retail sales of coffee are predicted to grow in the Brazilian market by 6 percent annually between 2008 and 2013, with arabica and fresh coffee beans expected to show the fastest growth.24 Specialty coffee shops in Brazil—such as Starbucks, Suplicy Cafés Especiais, Nespresso, and Espressamente Illy—are stimulating the consumption of fine and gourmet coffees in both the on-trade and off-trade channels.25 Thus, consumer preferences are changing, with more people wanting to taste different varieties of coffee and then buying the beans or ground coffee at supermarkets or specialty shops to replicate the experience at home.26 As a result, the appearance of more on-trade outlets will play a key role in stimulating the consumption of gourmet coffee.

Coffee growers and producers have invested in new distribution centers and signed agreements to offer more regionalized products and to expand points of sale by extending their reach in supermarkets.27 As more consumers search for new flavors for home consumption, supermarkets are dedicating more shelf space to gourmet coffee.28 For instance, in Pão de Açúcar, a prominent Brazilian supermarket chain, half the shelf space assigned to coffee is now occupied by fine and gourmet brands; and the supermarket has launched Qualitá, its own private gourmet label.29 The chain is also developing new marketing strategies to support the gourmet coffee sales. For example, it has created an exclusive website dedicated to improving consumers’ knowledge of fine and gourmet coffees.30

Euromonitor International reports that there are two growth opportunities in the Brazilian coffee industry. The increasing demand for espresso coffee machines has prompted manufacturers to offer a wider portfolio of higher-quality products to cater to affluent consumers, the only ones who are in a position to purchase the relatively expensive machines. The rapidly expanding college population also offers new opportunities for specialty coffee.31 According to ABIC, most coffee consumers tend to be adults aged 36 and older. Younger consumers prefer creamy beverages such as cappuccino and mocha.

Looking to the Future

Maria Helena’s efforts received national recognition when, in 2005, she was acknowledged as Brazil Woman Entrepreneur of the Year by SEBRAE, a govern ment agency that provides support to micro- and small enterprises. She remembers crying when, at the time, she wrote the story of her journey to entrepreneurship. She called it, “Past and Future in a Cup of Coffee.”

Maria Helena’s most important challenge continues to be further developing brand recognition. One of her current strategies includes developing partnerships with manufacturers of espresso machines as a way of encouraging coffee-shop and restaurant owners to carry Café Helena. In the meantime, she sells the unroasted and unbranded coffee from Monte Alto to distributors for export to international markets, where it is processed and sold by roasting companies. Ideally, she would like to export her branded coffee to markets such as the U.S., where demand for gourmet coffee is high and growing rapidly.

She has considered different channels, mainly selling through a distributor. However, language barriers and her lack of knowledge of international markets make her wary of embarking on internationalizing her brand at this point. She is not sure if she should pursue foreign markets at all or just focus all her resources and efforts on expanding her share of the Brazilian market.

Maria Helena’s future plans also include entering the field of “rural tourism.” However, she does not envision transforming the plantation into a hotel. Rather, she wants to give visitors to the region the opportunity to experience life on an authentic coffee plantation. She has been careful to preserve the traditions of the plantation while incorporating modern techniques. The high ceilings, century-old walls, and antique balconies, tables, and wooden chairs in the main building make for a warm and inviting environment that recreates the period of the old coffee plantations.

This project is still in its implementation phase. Maria Helena plans to offer a tour around the entire plantation, beginning at the coffee plants, moving to the roasting and sorting areas, stopping in the family’s solar room, and ending in a cafeteria where visitors can taste—and purchase—the different coffee varieties. She envisions offering other regional food products, as well as magazines and books providing information about the culture surrounding coffee. She is seeking partnerships with artisans in the region to promote this type of tourism. While she acknowledges this new endeavor falls outside the realm of her expertise, she believes tourism will provide added support to coffee plantations and hotels in the region.

Notes

1 Interview with Maria Helena Monteiro Alves in São Paulo, Brazil, by María Fernanda Trigo Alegre, May 21, 2009.

2 Ibid.

3 Prefeitura Municipal de Dourado, “Prefeitura de Dourado Responsabilidade de Todos,” April 2010, www.dourado.sp.gov.br (accessed April 10, 2010).

4 Ibid.

5 Ali Ahmad Hassan, “Um Toque Femenino No Agronegocio,” in Historias de Successo. Mulheres Empreendedoras Pequenas Empresas Região Sudeste. Brasilía, Brazil: SEBRAE, 2006, pp. 17–34.

6 Interview with Maria Helena Monteiro Alves.

7 Coffee—Brazil: Country Sector Briefing, Euromonitor International, September 2009.

8 U.S. Department of Agriculture, “Coffee: World Markets and Trade,” Circular Series, June 2009, http://ww2.fas.usda.gov/htp/coffee/2009/June_2009/2009_Coffee_June.pdf (accessed April 18, 2010).

9 Ali Ahmad Hassan, “O Passado e o Futuro na Xícara de Café,” in Batons, Sonhos e Determinação. Jeitos Femeninos de Empreender. São Paulo, Brazil: SEBRAE, 2, 2005–2006, pp. 12–19.

10 Hassan, “Um Toque Femenino No Agronegocio,” pp. 17–34.

11 Coffee—Brazil: Country Sector Briefing.

12 Ibid.

13 Coffee Basics, “Front Porch Coffee and Tea Company,” November 21, 2006, www.elysfrontporch.com/coffeebasics.html (accessed December 11, 2009).

14 Ibid.

15 Reg Coffey, “Coffey’s Coffee—The Dark Side of Coffee,” n.d., www.coffeyscoffee.com/thecoffees.html (accessed December 11, 2009).

16 Coffee Basics, “Front Porch Coffee and Tea Company.”

17 Interview with Maria Helena Monteiro Alves.

18 Coffee—Brazil.

19 Hassan, “Um Toque Femenino No Agronegocio,” pp. 17–34.

20 Coffee—Brazil.

21 Ibid.

22 Ibid.

23 Hassan,”Um Toque Femenino No Agronegocio,” pp. 17–34.

24 Coffee—Brazil.

25 Ibid.

26 Ibid.

27 Ibid.

28 Ibid.

29 Ibid.

30 Ibid.

31 Coffee—Brazil.