9 Maita Barrenechea and Mai10

Building a Travel Business

Gregory Gilbert

Currency devaluations, financial crises, and global recessions did not deter Maita Barrenechea from building her customized tours business in Argentina and other South American countries. She hit upon the idea almost by chance, and soon realized that it enabled her to bring together some of her passion for the outdoors and her desire to help her country develop a competitive industry.

The name Mai10 is intriguing.1 It is associated with the maiten tree in Patagonia, an area of spectacular natural beauty that, for many people, defines their image of Argentina. Mai10 also combines Mai, a nickname for the name Maita, and the number 10, which in Argentina signifies the top or best within any category. This unique combination of meanings and images wrapped into the company name of Mai10 was highly appropriate for the destination management company (DMC) that Maita Barrenechea founded in 1982 and nurtured and developed into the paradigm of tourism in Argentina. DMCs were the face of Argentine tourism for many of the world’s key executives, celebrities, and political leaders and for many ordinary foreigners seeking a customized travel experience within Argentina. The company’s name was appropriate because the business first began in Patagonia, and, while it had expanded to operate trips throughout South America, it remained firmly rooted in Argentina and, specifically, in the country’s areas of great natural beauty.

One of Barrenechea’s major goals in developing her company was to promote Argentina and its tourism industry and to show the country in the best possible light so the industry could grow for the good of all Argentines. Furthermore, the company unequivocally belonged to Barrenechea and was always her project and lifelong passion. She dedicated her life to ensuring that Mai10 offered the absolute premium, personalized travel experience to its clients without exception. As a result, the company began without any true competition in the industry, and the list of its accomplishments and accolades was long and impressive.

Mai10 specialized in tailor-made trips that were highly customized for free and independent travelers (FITs) and groups. Barrenechea stated, “A lot of time is invested in personalization . . . It’s a vacation and you are selling a dream.” During conversations with her, one got the sense that this principle was not only a business philosophy but also something that she personally believed in. She firmly believed that her clients worked very hard for their success in life and that their goal and reward for this effort was to have the free time and ability to truly enjoy the most incredible vacation possible. As a result, Barrenechea and her staff felt personally responsible for ensuring that each client’s interests were catered to and that all of them had the best vacation of their lives while under the care of Mai10. This passion to provide the perfect experience and the willingness to go to any length to satisfy her clients allowed Mai10 to expand its offerings and drove the company’s amazing growth over its long history. With twenty-five full-time employees and dozens of other long-time trusted freelance affiliates, the Mai10 operation grew into a large and smoothly functioning company that generated $3–4 million in annual revenues in 2008.

Early Development

Like most entrepreneurs, Barrenechea never intended to start her own business when she began her career. As a native Porteño (resident of Buenos Aires), she attended university in the Argentine capital and chose to study business administration. As might have been expected in Argentina in the 1970s, Barrenechea said that she was one of only two or three women in her class at the business school. As a result, from a young age she was used to independently following her goals and being something of an anomaly in the male-dominated world of Argentine business. After graduation, she went to work for her father in the family ranching and agriculture business. However, she soon sought greater challenges and moved on to work as a simultaneous translator between English and Spanish, eventually heading Argentina’s leading simultaneous interpretation school. Around this same Barrenechea married her first husband, Carlos Sanchez, who, like her, was very active and an enthusiastic participant in outdoor sports. Together they spent a significant amount of time hiking, fishing, skiing, and visiting the spectacular wild areas of Argentina. This personal interest, combined with her facility for languages, enabled her to establish and expand her business.

The business itself began by pure chance. Knowing her personal interests and knowledge of Argentina’s spectacular natural areas, in May 1982, a friend asked Barrenechea if she could help another individual organize a fishing trip to Argentina. Since her friend did not know of anyone or any organization capable of doing this, Barrenechea offered to organize it herself as a favor. The individual was so impressed that, the following year, he recommended Barrenechea to another friend but insisted that she charge for her services. This pattern of word of mouth marketing continued, and the number of trips Barrenechea organized increased. Initially, the trips were a hobby for Barrenechea and her husband, with their first trips being organized around fishing, primarily in Patagonia. Skiing was also a cornerstone of the early business, as it was a personal passion for Barrenechea and it was easy for her to bring clients to international ski competitions in the area around Bariloche.

Initially, the business was focused on Patagonia, where there was virtually no tourism development. Barrenechea had to be creative in establishing an infrastructure. Although there were no high quality hotels, there were beautiful, private second homes called estancias that wealthy Argentines allowed their friends to use when they were not living in them. Because these homes were expensive to maintain, Barrenechea convinced the owners to allow her and her paying guests to use their homes for a fee. This was challenging at first because the homes were not designed for guests, and the owners were not accustomed to the discriminating clients she was bringing to Patagonia. Barrenechea had to convince the owners that it was worth the money she was paying them to close off entire wings for her guests or to make other accommodations.

Barrenechea also encountered similar challenges in finding fishing and hunting guides. Because there were no professional guides in Patagonia, she had to teach local fishermen how to handle the highly demanding international clients she was accompanying. They needed to learn how to be guides; they were not permitted to fish with clients but rather had to teach the clients how to fish. Eventually, she was able to hire several fulltime fishing guides stationed in Patagonia. At this time, a specialized tourism company in the U.S. that was promoting her fishing tours and supplying her with clients asked if she could also organize bird shooting tours. Although Barrenechea knew nothing about bird shooting and hunting, she assumed she could learn the necessary information through some research. At that time, doves were considered a plague in Argentina, as they ate crops in the area, and the owners of the estancias were killing them by using poison. Since doves had been overhunted in the U.S., Barrenechea recognized an opportunity and was able to convince the estancia owners to stop poisoning the birds and, instead, allow her clients to shoot them, along with ducks and partridges. In 1990 she and her first husband opened her grand hunting lodge in Patagonia. For many years that lodge was considered the best in the country, although Barrenechea’s involvement with the lodge ceased following their separation in 1993.

Just as Barrenechea’s business had expanded from fishing and skiing into hunting, clients asked her to plan other trips, and she branched out into organizing trips for individuals or small groups that were focused around special interest activities. These activities multiplied to include golf, horse riding, polo, tango, photography, bird watching, horticulture, literature, architecture, opera, cattle study tours, grain tours, and art tours. For most of these special interest tours, Barrenechea used her contacts to personally learn about the activity and the location as well as to establish an infrastructure. In many areas, her personal interests and knowledge helped her significantly. She had studied art and architecture, had attended the opera with her grandfather since childhood, and was well versed in the grain and cattle industries through her family’s business. In general, all of her clients’ special interests were of interest to her, and she was therefore willing to invest the time to learn about them, or had appropriate contacts that enabled her to organize a memorable trip.

When organizing the first trip for a new special interest tour, Barrenechea invested a significant amount of time in researching and learning about the subject and determining the ideal itinerary for the trip to meet her clients’ desires and needs. She always visited hotels and facilities, such as golf courses and museums, to ensure that everything would be up to the standards that her clients expected. As her business grew, it was less critical for Barrenechea to accompany her guests because she had cultivated trusted, freelance guides in various parts of Argentina who took on this responsibility for her. As a result, even though she was able to run the business from Buenos Aires, she never stopped participating in business development.

While developing the business for small, special interest groups, Barrenechea began taking on FITs—families or individuals who were not interested in traveling with a larger group. Given the high level of quality and service that Barrenechea provided, these clients tended to be wealthy, although she was always able to offer a range of cost options so that not every tour was at the high end in terms of prices and services offered. Instead of focusing on cost and luxury, the guiding principle behind this business—just as it was for the special interest groups—was to customize each trip according to the needs and interests of the clients. While it might not have seemed worth the effort from a business angle to plan highly personalized trips for a single individual or small group, Barrenechea realized early on that these clients were her best form of publicity through word of mouth advertising. They always brought her new clients and were instrumental in helping develop the group portion of her business. As a result, even as the company grew over time to become a much larger entity, Barrenechea maintained the FIT business as a major component of Mai10.

In 1987 a former Kenyan client requested that Barrenechea organize a trip for a much larger group, the Young Presidents’ Organization (YPO), a global organization of CEOs under the age of 50. These were over-stressed, highly active, demanding individuals who were used to personalized attention, and they easily fit within Barrenechea’s typical clientele. Just as she had done previously with new types of groups, Barrenechea immediately accepted the offer and assumed she could organize a trip for a group of between 900 and 1,000 people. Since the trip was not scheduled to take place until 1989, Barrenechea had 2 years to organize all of the events, which were designed to be distinctive, impressive, and of the highest quality, given her highly discerning audience. Over ninety activities were arranged for the group, including a talk by the Dalai Lama, as well as individualized pre- and post-tour activities for many of the participants.

The YPO trip was a huge success and gave Barrenechea the confidence to cater to large groups. Around the same time, she organized a similarly high-profile event for a summit of vice presidents, finance ministers, and associated staff from every country in Latin America. She took on the challenge with her now well-recognized entrepreneurial approach and organized a successful tour.

Despite the success of these large group trips, in the early 1990s Barrenechea returned to her core business of special interest and FIT groups. She had never wanted to build a large group business and the complexity and intensity of planning these events to her exceedingly high standards would have made it difficult to incorporate these types of trips as a regular part of her business without growing Mai10 significantly and risking a decline in overall quality. Furthermore, the large group business was irregular in timing and group size, making it a risky prospect to focus on this type of business. During this time she marketed her business primarily through word of mouth, augmented by several trips each year to Europe and the U.S. These trips were initiated by individuals who invited her to their clubs or homes to speak with friends and associates who were interested in Argentina and Barrenechea’s services. Barrenechea felt that by promoting Argentina, rather than her tours and her company, her business would grow through highlighting the opportunities to travel in Argentina, rather than through an aggressive sales pitch. As a result, Mai10 grew organically.

Expanding the Business

While Mai10’s growth had been consistent, by 1993 it was still a relatively small company and operating it was time-consuming for Barrenechea. Despite the YPO and the Latin American vice presidential group tours, the business primarily comprised fishing and hunting trips and a small component of special interest and FIT clients. In addition to Barrenechea and her first husband, there were only one or two full-time employees working in Buenos Aires, and the business was seasonal. Ultimately, that year brought dramatic changes for Barrenechea and Mai10. Barrenechea separated from her husband—she later remarried—and chose to remain in Buenos Aires with her three daughters. After dividing up the business with her first husband, Barrenechea continued to run Mai10, while her ex-husband kept the hunting lodge in Patagonia.

At that time, Barrenechea decided it was time to take truly proactive steps to expand and organize her business. She developed a business plan, a marketing plan, and an operations manual detailing business practices for Mai10 employees, formalizing and codifying the company’s principles and procedures. She also invested her own money to create marketing materials to bring to conferences. Part of her marketing plan included the commitment to build a corporate business and market the Argentine tourism industry and Mai10 in more professional and formalized forums. Instead of depending solely on word of mouth marketing, Barrenechea traveled to the U.S. and Europe to actively promote her business.

Despite this focus on building her company, Barrenechea’s marketing philosophy remained the same. She consistently focused more on enhancing global awareness of Argentina as a tourist destination rather than selling her company. She believed that by expanding the Argentine tourism industry in general, she would increase the overall market and Mai10 would benefit as a consequence. This attitude extended to her frequent interactions with foreign media who came to see her when they visited Argentina. When speaking to or meeting with these reporters, Barrenechea always focused first on promoting the country. She viewed reporters’ recommendations of her services as a fortunate by-product.

In marketing Argentina and Mai10, Barrenechea had first begun attending fishing shows and then general travel shows. Initially, she went mainly to Europe to increase awareness. Prior to 1993, approximately 90 percent of her clients came from the U.S., but Barrenechea recognized that she could not focus solely on the American market and needed to target other markets as well. As a result, she began to travel to England, Germany, France, Spain, and other Western European countries to garner business. Her efforts ultimately yielded a pool of clients who were nearly evenly divided between Americans and Europeans. She also had a significant number in Australia and South Africa. Barrenechea continued her intensive marketing abroad, traveling to the U.S. and Europe about five times a year for large travel conferences and other marketing events. These events were typically forums to meet with travel agents or tour organizers in order to enhance Argentina’s image as a tourist destination and to inspire clients to seek out Mai10.

From 1993 onward, Barrenechea’s efforts to enhance the global profile of the Argentine tourism industry and to expand her business paid handsome dividends. Mai10 grew much faster than she had expected, and Argentina itself benefitted from significant tourism booms. The country became a hotspot of global tourism and the subject of countless travel articles, many of which mentioned Barrenechea. The business also expanded beyond Argentina, as demand from previous clients warranted, with Mai10 running trips to every South American country except Colombia and Venezuela. By 2008, Mai10 had twenty-five full-time employees working in the Buenos Aires office, all of whom were managed directly by Barrenechea and her second husband, José García Calvo, whom she married in 1998 (see Figure 9.1). In addition, there were countless part-time and freelance employees who served as guides, greeters, and drivers throughout Argentina and South America. Whenever Barrenechea hosted a

Figure 9.1 Maita Barrenechea

Source: Reproduced with permission from Maita Barrenechea, July 29, 2012.

particularly large group with a complicated itinerary, the company might have as many as 200 different people working simultaneously under the Mai10 name.

In the Buenos Aires office in 2008, employees comprised two divisions: the groups division, which organized trips for groups of twenty or more people, and the FIT division, which organized trips for independent travelers or much smaller groups. Since a larger percentage of Mai10’s business was with smaller groups, there were more people employed in the groups division. Within each division, employees were also divided into two functional groups: planning and operations. The former group worked directly with potential clients to plan and sell trips to fit their needs. Barrenechea and Calvo were very involved in the planning group, with Barrenechea focusing on FIT clients while her husband focused on the larger groups. After a trip was sold, it was passed along to the operations group which then handled all of the bookings and reservations. These employees then also ensured that the trip was successful and problem-free. This was an area in which Barrenechea and Calvo had much less involvement.

Because Barrenechea continued to broaden the spectrum of trips that she offered by adding new locations or developing new types of specialized trips, she had to continue to train new specialized guides. She said, “The most fun part of my job is inventing new, different, and original programs, and this process carries with it the need to train those who will actually run the trips.” Fortunately, the Argentine tourism industry had advanced significantly since the early 1980s, and there was little need to continue to train guides about general tourism and how to interact with guests. Being a tour guide had become an institutionalized career with a range of specialized courses and training programs available, and this development certainly enhanced the process of choosing and training guides to work for Mai10.

Keys to Success and Challenges

Profitability for the business ranged between 8 percent and 15 percent, depending on which groups ultimately decided to travel with Mai10 and which trips they eventually chose. Costs were more or less fixed and different products and services had different profit margins, making overall profitability relatively variable. Not only did Barrenechea invest significant effort and her own money into formalizing and expanding the business in 1993, but, like most entrepreneurs, she was involved in every aspect of her business. At first she performed all tasks, and, although she had a great deal of help in virtually all capacities, she continued to maintain close control over all aspects of the business, along with Calvo. Either one of them personally answered any query that Mai10 received from a potential client, and one of them was often in the office on weekends and always on call to take care of any emergencies that might arise.

Despite the fact that she ran a business that provided people with the most memorable vacations of their lives, Barrenechea and her husband rarely ever had time to take a vacation of their own. Their intense focus on providing their clients with the highest level of personalization and customer service required a significant amount of time, with Barrenechea always wanting to be personally involved in ensuring that the expectations of every client were always exceeded. While she was able to pass along some responsibilities to her employees and Calvo, Barrenechea’s focus on marketing and planning for her growing company also became more time-consuming, and finding a way to balance these demands with her personal life was sometimes challenging.

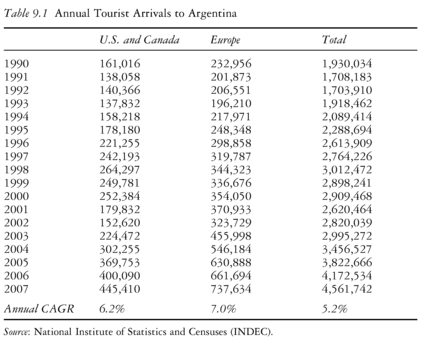

With a larger business and an expanding Argentine tourism industry, Barrenechea and Mai10 had to confront other challenges that arose (see Tables 9.1 and 9.2). Competition grew over the years. As of 2008, there were many other DMCs sending FITs and larger groups to Argentina for a variety of trips. Mai10 maintained its advantage, however, by focusing on the personalization and superior service that its larger competitors such as Abercombie & Kent lacked, while the smaller competitors could not match Barrenechea’s reputation as an expert on Argentine tourism. Her competitive edge was also enhanced by the recommendations of her former clients, with word of mouth advertising consistently bringing Mai10 50 percent of its new clients. Although she wanted to continue to expand her business, she became discriminating about whom she accepted as clients, carefully screening each and every potential new guest. Additional challenges arose from the Internet, as it provided individuals with the ability to plan their own trips and created more transparency regarding pricing, something which negatively impacted profit margins over time. Nonetheless, Mai10’s focus on superior service and attention to detail, as well as Barrenechea’s longstanding relationships with hotels and tour operators, enabled the firm to continue to grow.

Competition from other DMCs and shrinking profit margins were not the only difficulties that Barrenechea encountered over time. Operating a business in Argentina brought other challenges. As Barrenechea stated, “The primary difficulty was the lack of infrastructure that persisted in the country.” When she ran her first trip in 1982, Buenos Aires’s iconic Alvear Palace Hotel was closed and the famous Llao Llao Hotel in Bariloche was in disrepair, leaving the country with no luxury hotels. While the variety and quality of hotels and restaurants multiplied dramatically after 1980s, there was still a notable lack of helicopters and private jets available for charter, and a railroad network did not exist. Furthermore, there was a scarcity of domestic commercial flights, and the domestic airline company, Aerolineas Argentinas S.A., had a terrible reputation, was massively inefficient, and was a target for government takeover.

This threat of nationalization highlighted another major challenge to doing business in Argentina. The country had long been avoided by major

international investors, largely due to its economic and political instability. While this view has long been pervasive in the consciousness of the Argentine public, since 2001 the greatest concern has been over how the govern ment would treat bank deposits. In that year the govern ment prevented Argentines from withdrawing their deposits, an action known as el corralito. At the time, the Argentine peso was fixed at 1-to-1 with the U.S. dollar, and el corralito was followed by a devaluation of the peso. As a result, many Argentines saw their savings cut by two thirds. Fortunately, Calvo anticipated the devaluation and Mai10 took the necessary actions to protect their capital, averting disaster for the company. Nonetheless, the constant fear that the economy might easily collapse again or that the govern ment might take drastic measures that would tremendously damage businesses was a constant and very real threat for Barrenechea and her company. As a result, Mai10 maintained most of its capital in foreign currency.

Another challenge for Mai10 that was unique to operating a business within Argentina was the exposure to inflation risk. Inflation was typically quite high in Argentina and had long posed a problem for local businesses. Since Mai10 often quoted and booked trips over a year in advance, Barrenechea had to manage the risk that her profits would be eroded by inflation in the interim. Fortunately, most hotels and other service providers quoted her fixed rates 6–12 months in advance, assuming the inflation risks themselves. Whenever this was not the case, Mai10 inserted clauses into its contracts indicating that costs and prices in Argentina were often subject to sudden change and that clients needed to be prepared to assume any potential cost increases. While this minimized Mai10’s risk of price hikes in flights or other services, Barrenechea did not want to pass on large increases to her clients indiscriminately. Furthermore, it was difficult to pass on any necessary increases in her employees’ and freelance guides’ salaries that were due to inflation. Mai10 therefore estimated the likely inflation, charged her clients by installment and also paid service providers and other creditors in this way, coordinating the timing and scale of the corresponding inflows and outflows of cash so that the minimum amount of money was held in Argentine bank accounts and exposed to inflation. In addition, Mai10 took great care to draw on foreign currency deposits or payments to pay the costs of trips only when absolutely necessary. These measures served as important hedges against both inflation and potential capital seizure by the government.

In addition to the economic problems that appeared to be endemic in Argentina, Mai10 was also exposed to other risks and challenges that were specific to the tourism industry. As Barrenechea stated, “Tourism is an industry that is very sensitive to the political, economic, security, and health problems that very often afflict countries such as ours and the global or regional issues impacting the countries from where our clients arrive.” Certainly, the great security fears generated by the terrorist attacks on New York City on September 11, 2001, hurt tourism globally and also affected travel to Argentina.

Another example was the global news generated by el corralito in 2001, which resonated with many Europeans and North Americans and damaged the image of Argentina as a tourist destination. As a result, tourism declined and one of Mai10’s groups canceled its trip. However, the devaluation of the peso also had the benefit of making the country less expensive for foreign travelers, and in the end this counterbalanced the fear of traveling to Argentina and helped to encourage and expand the country’s tourism sector.

Gender as a Challenge

Perhaps the greatest potential challenge for a woman running her own company in Latin America was the fact that she was functioning within a male-dominated business society. For Barrenechea, however, this factor was never a major impediment during her impressive trajectory. In speaking with her, one felt that she had never really considered the issue, either because it was never even a minor challenge or because she was so driven in her path that such distractions had never caught her attention. While Argentina was certainly a society where the macho culture was prevalent, the tourism industry was more heavily populated by women. For example, Barrenechea observed that the general manager of the Alvear Palace Hotel, the finest hotel in Buenos Aires, was a woman and that there were many women working in marketing within the industry. Nonetheless, Barrenechea had been working with and dealing with men throughout the development of Mai10, from owners of estancias to fishing guides, hotel owners, and managers. These individuals may at first have been skeptical of such a strong Argentine woman making demands of them, but her natural charisma and talent ultimately won them over. As a result, Barrenechea never felt that being a woman was a challenge in growing her business, and, perhaps, her personal nature was such that the challenge was not as noticeable to her. It was also true that, since the industry was still in its infancy when she started Mai10, Barrenechea was not yet operating within an established system or male-dominated industry. Instead, she helped to develop tourism in Argentina and made Mai10 a major pillar in the industry’s foundation.

Looking Toward the Future

Mai10’s success as a business resulted in increased tourism to Argentina. Over the years Barrenechea has received various awards and repeated recognition by publications such as Travel + Leisure, Conde Nast Traveler, and National Geographic. In 2009 Barrenechea was continuing to strive to refine her business. While the global recession and increased competition within the South American tourism industry continued to present difficulties for Mai10, Barrenechea was considering the different ways she might adapt her business to prepare for the challenges ahead.

Note

1 Most of the information presented in this case is based on interviews with Maita Barrenechea conducted in December 2008.