16 Annette Zamora’s Naz y Rongo

A Scavenger Hunt in Search of the Culture of Rapa Nui

Leeatt Rothschild

Schoolteachers often take to entrepreneurship. They have organized schools, launched educational programs, started publishing houses, and sometimes joined their students in the pursuit of new ventures. Annette Zamora saw a need for classroom materials highlighting the local culture of the Rapa Nui, in the South Pacific. She launched a magazine and fashioned a scavenger hunt that proved popular with tourists as well as schoolchildren.

More than 3,000 nautical miles west of Chile is Rapa Nui, the “navel of the world,” an enchanting volcanic island of 64 square miles that is home to one of the world’s most distinctive cultures and famous for its monumental statues and ceremonial sites. Rapa Nui constitutes the easternmost point of this distinct Polynesian cultural triangle, with Hawaii to the north and New Zealand to the west. Preserving the fragile identity of Rapa Nui (also known as Easter Island) is the ultimate goal of Annette Zamora, a cultural entrepreneur who has enriched the lives of others by ensuring that her island’s unique history and culture are preserved and cultivated by future generations.

Annette frames her dedication to promoting the diffusion of the Rapa Nui culture by saying, “when you believe in something, you will do anything for it”—a credo that has inspired her even in the toughest times. Trained as a teacher, she left the comforts and benefits of a classroom to start a comic book series and foundation to educate the young about the Rapa Nui culture. The daughter of a Rapanui mother and a mainland Chilean father, Annette was raised alone by her grandmother in Santiago. Her return to isolated Easter Island reflected her love for Rapa Nui—the indigenous culture and the people of the island. Her Foundation ECHO captures just a morsel of her passion and dedication to ensuring this culture continues.

Coming of Age in Santiago and the South Pacific

Annette’s early years were filled with hardship, and she developed a striking maturity from those challenging experiences. She recounts memories of carrying heavy items, traveling across Santiago with her grandmother, and living a simple life. “I was raised like a bird: I ate the fruits around me, rose and slept with the sun; total liberty with no rules.” But she always had a sense of uneasiness in not knowing who her father was. Through the difficulties of those years, she developed a precocious sense of appreciation. When her grandmother bought her a cookie, she recalls valuing the gesture more than the actual treat, an action she was quite young to appreciate as a child. “As a youngster I learned how to survive and from that I learned how to be happy despite the hardship of my life.”

Annette’s petite frame, high cheekbones, and charismatic eyes complement the passion and strength of her voice. She is direct in her speech and is aware of who she is. After all, she was pregnant as she pursued her master’s in pedagogy at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile—an institution known for helping women with children succeed academically. Annette promised herself that when she left Santiago to pursue her master’s, she would not return to Easter Island without it. “I am persistent; and once I say I will do something, I do it.” This explains how she successfully completed her degree, despite being a divorced mother of two in a foreign place with no family to support her. Her perseverance encourages her to push her ideas forward and allows her to continue developing Foundation ECHO despite the challenges.

Rapa Nui is unlike any other place in the world. It is an isolated, inhabited gem in the middle of the Pacific Ocean, dotted with over 360 massive moai statues that were built by the Rapanui people to serve as representative figures of sacred chiefs and gods.1 It appears as if the original settlers first came from the Marquesas Islands around 800 CE; and genetic evidence supports a massive prehistoric settlement from Polynesia.2 The first European visitors were the Dutch explorers who came upon the island on Easter Sunday, 1722. Rapa Nui had a turbulent history of conquests and foreign attacks and eventually became a Chilean colony in 1888, when twelve Rapanui chiefs ceded control to the Chilean captain, Policarpo Toro Hurtado.3 Its history has intrigued archaeologists and historians alike, and today attracts over 46,000 tourists annually. Tourism fuels the island and represents 91 percent of its economy, generating over US$20 million annually. The Chilean govern ment estimates that the island’s population was 4,888 in 2010, the vast majority of whom are native Rapanui.4 The island’s three schools, spanning primary through high school, teach approximately 250 students.

The idea of starting Foundation ECHO to promote educational activities related to the Rapa Nui culture did not occur to Annette in one fell swoop. As a teacher, she was asked to travel to Hawaii to join the Annual Polynesian Congress—a meeting involving Micronesian and other Pacific islands with the goal of sharing best practices to preserve the native cultures. This gathering marked a pivotal point in which Annette was introduced to a broader movement whose goal included the very issues she struggled with in the classroom.

In general, Rapa Nui was seen as purely folkloric. Apart from a dance or two, teachers did not feel an obligation to teach the island’s history and culture to their students. Annette was different. She felt a keen obligation to educate her students about the Rapa Nui culture and to teach them the language. After all, she said,

I had a tremendous responsibility—I was working with the future of the island; they are the new generation who will be responsible for the Rapa Nui culture. If they do not understand their own heritage, how will their ancient traditions continue?

This question plagued Annette. Preserving an indigenous culture is generally thought of as a community endeavor. Annette, however, was not content with sitting idle and waiting for others to take charge. She is not wired that way. This was an issue that concerned the future of her island and her people, and she wanted to do something about it. As a teacher, she was tasked with teaching her students the Rapa Nui alphabet and cultural values. She took this educational mandate personally; and the evolution of how she interpreted and internalized this task brings us to her comic book series and Foundation ECHO.

A Cultural Entrepreneur Is Born

What do you do when you find current didactic materials limiting, are passionate about teaching a rare topic, and do not want to wait for others to make things happen? Simple: you start a comic book series featuring two lovable indigenous cartoon characters, find the best artist in town, add a scavenger hunt, and watch your idea snowball into the island’s most coveted monthly publication. At least that is what Annette Zamora did.

Annette should have known her comic book series, Naz y Rongo, would be a hit. When she began teaching the Rapa Nui alphabet to her first-grade students and felt that her teaching materials were lacking, she made an artistic alphabet banner for her classroom. It was such a success that letters disappeared on a daily basis—carried home in someone’s bag for sure. Recounting the story, Annette smiles. Although the alphabet was supposed to stay in the classroom, she knows the banner educated her students as she had intended.

Naz y Rongo not only allows students to learn about their native culture, but also forces them to get out of the classroom and explore their island. Annette is aware of both the big picture and the finer details.

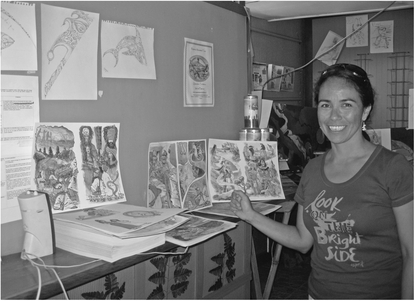

Figure 16.1 Annette Zamora with Drawings for the Comic Naz y Rongo

Source: Leeatt Rothschild, May 2009.

She understands her audience and her ultimate goal and creates the appropriate tools to combine both. She knows how children learn best, decided that fostering Rapa Nui education was critical, and determined that an experiential scavenger hunt was the best way to entwine the two. The result was a comic book that includes a scavenger hunt led by two indigenous characters who engage readers to use clues to seek answers physically.

Naz y Rongo takes readers on a real scavenger hunt. It requires people to explore the island to seek clues that guide them through a multi-episode scavenger hunt. The more you explore, the more clues you gather, and the closer you get to the final answer—revealed at the end of the school year, of course, for full suspense. Children have to interview the island’s elders to learn customs and Rapa Nui phrases, and travel to moai sculptures or other archeological sites to find clues. This ensures that the children are fully captivated by and immersed in the learning process.

Thinking up the comic book series was already a huge feat. Bringing it to life from a mere germ of an idea was yet another. Doing so on an island 2,000 miles from any major city, with absolutely no cash to invest, where photocopying class material was a struggle, added a few more complications. But this was business as usual for Annette; and when she plans to do something, she makes it happen.

With the help of a mother at her school, Annette started the educational magazine/comic book strip. They decided to create two protagonist cartoon characters: Rongo, a messenger in Rapa Nui who is also found on a petroglyph on the northern part of the island, and Naz, who represents the ancient Nazca lines. Consistent with her philosophy of getting students involved in the learning process, Annette organized a contest to have the children select the final figures and colors of the characters. She enlisted a friend, an extraordinary artist on the island, to draw the comic strips and help design the magazine.

In 2005 the collaborators created the first eight pages of the comic book. In 2006 they published the first full Naz y Rongo series: ten monthly magazines. With the help of her American partner, John, Annette was able to raise funds to have enough copies of the series for 1,500 students printed in Kingston, New York, and shipped back to Rapa Nui.

What distinguishes Annette is not only her passion for the Rapa Nui culture, but also her sincere belief that she has a responsibility to educate the future Rapa Nui generations and her drive to make the most fantastic ideas come to life.

Although the magazine targets children and teens between the ages of 5 and 18, Annette soon saw the sweeping success of her work. “Adults would all stop me and say, I went to ‘X’ cultural site to try to figure out the clue.” The idea was to integrate the entire island community into education about its collective heritage. “Kids had to look for clues and ask their siblings, parents and grandparents. . . . [T]he idea behind this was to have people discover the island.” Despite the first edition’s success, Annette has never forgotten the struggles of her efforts; nor does she pretend everyone was behind her work. “It was beautiful [the collective efforts], interesting, but also hard. Hard because people say they support you but then you see that that isn’t so. They wonder where the economic value lies for them.” And if they do not see how they will benefit from supporting her efforts, they ask, “Why should I help you?”

For this reason, all the funding and a tremendous amount of support came from the United States:

Because I had an issue showing my emotions in front of my people, knowing their rejection of my efforts, the [low] level of awareness and interest they had, I sought funding from New York. There was more awareness in New York than from here. And there was much more bureaucracy, ways in which the island just made fun of me.

At the same time she and her colleagues were compiling the first edition of Naz y Rongo, Annette was working on a television program focused on social issues. She interviewed doctors, nurses, and hospital workers for a program designed to teach the people of Easter Island about modern hospital care. She translated all the material into the Rapa Nui language, which was a key element for the show. She also started an exhibition of contemporary Rapa Nui art by local artists. Here she worked with the older generation and imparted to them why she felt the necessity to better understand their culture from within. “Because we are so few, it’s that much more important to know who everyone is—what we do, how we work.”

Building Support

As much as people loved the magazine, they were unwilling to pay for it. Annette could not sell it on the island because people would not buy it. And yet she felt an innate calling to continue the beloved publication, for four years, as a not-for-profit endeavor. The first year each issue was 8 pages; the second year, 12 pages; and the third year, 16 pages. For the fourth year, each issue should have been 20 pages; but Annette and her collaborators lacked the funds and kept it at 16 pages. By the second year, they were able to convince LAN Chile, the country’s national airline, to sponsor the shipment of the magazines.

On Rapa Nui, Annette met with government agencies and the mayor to solicit funding. Upon discovering that the magazine was written in both the Rapa Nui language and Spanish, no one was willing to provide any financial support. Annette’s desire to teach the young generation their native language stems from the fact that every year the population that speaks this language shrinks even more. To her, the need to educate the children was obvious. The government, mayor, and other agencies were stuck on imagining the bilingual nature of the island’s people—“they didn’t understand the linguistic reality of the island.” This is why Annette has been so fervent about teaching the young generation its own heritage’s native language.

Annette saw her connection to Rapa Nui as one of many individuals who connect past to present to future. And although she recognizes she is merely one person, she takes her role in that lineage very seriously.

What I am about to say might sound discriminating, but my work was focused on stimulating the Rapanui to wake up, to sense the importance that we need to leave our mark. We have the moai from our ancestors. What are we going to leave behind?

Sometimes we were up until three or four in the morning. Everyone says it’s good that I am doing this but no one is ready to give me money. Everyone is happy I am doing it . . . but nothing more. It was very hard, a challenge to even find money for printing. Sometimes it’s not that easy to believe in your own dream because you can think that you are crazy.

Up until the third year, all the funding came from the United States— approximately $12,000 from generous philanthropic donations and people’s desires to help. “Not that any of this money came to me. I only paid the painter . . . [W]hen you have a dream you sacrifice more than you imagine.” In 2009, the fourth year of publication, Annette noted,

this year will be the first one within the last four where I will actually earn some money. It is through a project I am doing with UNICEF. I am happy because someone is paying me so I can continue investigating something that I love.

Annette, her assistant Ulla, and painter Po worked in a small office off the main entrance to the town’s most centrally located hotel. Annette was able to guarantee this work space, and they have a small storefront that leads to their office, as well as a back room that serves as the painter’s studio. The studio has colorful drawings of Naz y Rongo pinned all over the wall, as well as various UNICEF project pieces propped up on a table. A large easel stands in the middle of the room, beside a desk that has dozens of paints, oils and crayons—a Mecca of tools for any artist.

Although the front-room office space is equipped with a computer and printer, the remainder of the room is reserved for showcasing items for sale: mugs and t-shirts with the Naz y Rongo theme, other Easter Island paraphernalia, CD-ROMs, batteries, and the like. Annette explains that she spent countless hours running around various agencies, meeting with officials in Santiago just to solicit grants of $1,000 or $5,000. She complained:

So many documents . . . more papers, filling out more papers. You waste more of your time trying to get these funds. We said we had to invent more ways [to raise money], so we made mugs, t-shirts, stickers, which all serve as sources of funding.

By selling some of these items Annette and her colleagues could offset the basic costs of maintaining the office: “I have many dreams but I am a realist.” Annette is a dreamer in that the challenges of launching Naz y Rongo would have prevented most individuals from even attempting such an undertaking. At the same time, she is a realist—once she puts into practice what she has ingeniously imagined, she takes action to make it a successful reality, for example by selling works of art for profit and persuading LAN Chile to sponsor printing shipments. After all, “The mom, my assistant, doesn’t get paid. I can’t ask her to always help me, work with me, if I do not pay her.” Faced with this reality, Annette creatively seeks other ways to generate revenue. Moreover, given the challenges of setting Naz y Rongo into motion, she knows that, in order for Foundation ECHO to survive, she needs to seek self-funded projects. One result of this is her current project with the government group CONADI (the National Corporation of Indigenous Development)—a guidebook in Spanish and the Rapa Nui language about the process of pregnancy and delivery.

The magazine went far beyond what I imagined as a teacher. People wanted to participate. But it was hard because many people don’t read. So it was harder for them to [follow the scavenger hunt]. I go against a concept here that assumes that one needn’t make a magazine or newspaper because people don’t read. But I say, well, at a certain point we’ll need to teach them to read. So I go against that thought. I believe it’s a role I’m assuming—the role of educating everyone, for everyone. Without waiting for anything. Give something for your own culture.

As Annette explains,

the goal of Naz y Rongo, in addition to teaching and stimulating children, is to invite the students to be the next painters, to do the interviews with the elderly to gain information, to contribute pieces to the magazine, etc. . . . under the supervision of the Foundation.

Annette is a big thinker, but she also considers how to make the Foundation sustainable. Given that the children have written back with comments and responses over the past few years, her ultimate goal is not too far-fetched. At the same time, Annette discloses that she has often considered stopping Naz y Rongo, “because I didn’t have any more energy. More than that, it was because I left my own children aside because I was immersed in all this. But I can never leave this aside because I love it.” She describes this vicious cycle by saying simply, “Mother’s guilt.”

Moving Forward

Annette never stops dreaming. When asked about where she sees the Foundation in 5–10 years, she says, “developing new lines of educational activities. New areas such as agriculture, social work. . . . I want to affect even more people.” As a child, Annette loved studying and developing herself intellectually.

I never thought I would start a Foundation, but I recall being a kid and thinking about creating new books. I remember a book that I used in the fourth grade and thinking, “I wonder how they created this,” and wanting to know how I could make it. I looked at each page, drawing.

Pensively, Annette adds, “I thought I would be doing something big, even bigger perhaps, than what I am doing now; the Foundation keeps me awake—it is an intellectual challenge.”

Annette is humble. Her work ethic shows in her actions and the way she views the Foundation. When asked why she thinks she has been successful, she responds,

I don’t know if I have been successful. I have received recognition but I don’t know that I have a clear concept of what successful means. The Foundation—I see it as yet another thing that I should have done; I see it as an accomplishment only in that I achieved something I hoped to do.

Officially, Annette is president of the Foundation. But if you ask her what her role is, she will tell you, “I think. I generate. I seek. I establish. [A]nd when the first steps are made, I develop, stimulate, push at the end, and I deliver. Then I continue all over again.” Annette’s perseverance and dedication will be tested in the coming years. Given that the Foundation’s initiatives require significant support from others, Annette will not enjoy any respite from seeking partnerships to develop her ideas, soliciting funding, or generating support from dissident opinions on the island. These obstacles have not stopped her from realizing her dreams to date. She hopes they never keep her from reaching her goals, because her creativity and passion allow her to go against all the odds to serve and educate her people and preserve her native Rapa Nui culture.

Notes

1 Shawn McLaughlin, The Complete Guide to Easter Island (Los Osos, CA: Easter Island Foundation, 2007), pp. 6–19.

2 Ibid., p. 15.

3 Ibid., p. 24.

4 Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas de Chile, Población y Sociedad Aspectos Demográficos (Santiago de Chile: Departamento de Estadísticas Demográficas y Vitales, 2008), p. 40.