| 3 | Ellis Island, New York Harbor: time closes in on a national cultural treasure |

Introduction

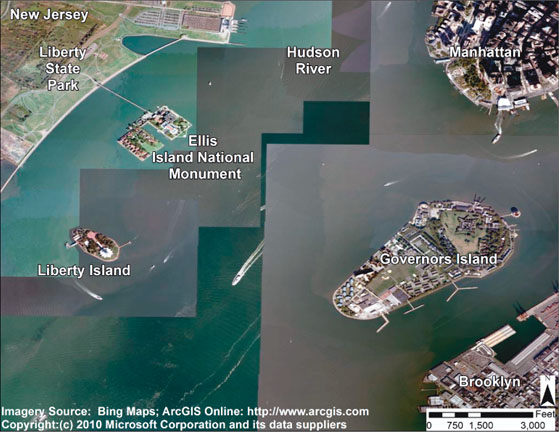

More than a dozen national parks are located in New York Harbor and immediately adjacent areas of New York City and northern New Jersey. These include the Statue of Liberty, its northern neighbor Ellis Island about half a mile away, its southeastern neighbor Governors Island, the Gateway National Recreation area in Jamaica Bay, and the African Burial Ground National Monument in lower Manhattan (Figure 3.1). Ellis Island, the focus of this chapter, is one of the most important cultural sites in the United States, and arguably is the one most in need of attention because of physical deterioration of the physical structures on the South Island. This chapter examines the final EIS documents and management plans for Ellis Island as an illustration of an EIS process that has focused on cultural and historical attributes.

From January 1, 1892 to November 12, 1954, Ellis Island was the major port of entry for migrants. Over 12 million people entered the United States through Ellis Island, the vast majority disembarking from cramped quarters in steamships. Twelve million may not seem like a large number in a population of over 300 million US residents in 2009. Yet about 40% of Americans, including this author, can trace their family history through Ellis Island.

When the Island's immigration function ended, buildings on the 27.5-acre site began to degrade. In 1965, President Lyndon Johnson added Ellis Island

Ellis Island and environs

to the national park system as a part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument. With federal funding, the main building on the north side (see Figure 3.2) was reopened to the public in 1990 as the Ellis Island Immigration Museum, and then two adjacent buildings were rehabilitated as offices. The National Park Service (NPS) maintains and has stabilized the south side, and one of the buildings has been restored. But the remaining twenty-nine buildings, which include the medical facilities for immigrants, probably will need to be demolished in 10–20 years unless there is an intervention (see Figures 3.3 and 3.4 for illustrations of deterioration).

The question before the US government and its elected officials is: Is immigration a sufficiently powerful force in the United States to warrant rehabilitation and reuse of the remainder of Ellis Island in ways that will honor its historic role? The number of immigrants in the United States has been rising, reaching record numbers in some cities and states. Many of these immigrant groups are minorities with relatively high fertility rates. Some suggest that a “browning of America” is occurring and that eventually non-Hispanic Whites will be the ethnic minority (Time Magazine 1990). Padilla (1977) observed that if these trends continue, it is possible that, by the year 2040, one in four US residents will be foreign-born. The US Census Bureau projected that in 2050 only half of the US population will be non-Hispanic Whites (Malone et al. 2003). In August 2008, it changed the estimate to 2042. In other words, the process is moving more quickly than had been anticipated.

New Jersey and New York border Ellis Island, and rank second and third, respectively, in their proportion of foreign-born residents (California ranks first). New Jersey's and New York's foreign-born populations are the most diverse in terms of the number of ethnic groups (Lapham 1993). These states are a forerunner of the changing demographics of the United States.

But assuming that immigrants should be honored by expanding the Ellis Island shrine is an arguable contention. Controversy surrounds the impact of immigrants on the economy, and especially jobs (Stryker 1987; Schneider 2007). Do immigrants take jobs away from Americans born in the country? Or do they work in jobs that other Americans will not? Given that many immigrants are highly successful, as measured by family income and education, do immigrants, on balance, create jobs for all Americans? Public perception of whether or not immigration is “good” or “bad” for the nation clusters in certain locations and within certain groups, and has become a political issue in some locations.

While some criticize immigrants, the image of the United States as a melting pot is rooted in the continual influx of immigrants, their sacrifice and hard work, and eventual assimilation of many into society (Glazer and Moynihan 1970). Indeed, some scholars credit high levels of civic participation among some US populations to immigrants and to intermarriage of immigrants (Hirschman 2005). The New York Daily News holds a Fourth of July essay contest. The winners in 2009 were five 8- to 12-year-olds, and their essays

Ellis Island

Deteriorating structures on South Island

Deteriorating structures on South Island

spoke with reverence about their grandparents or parents who migrated from Italy, the Philippines, and Poland. A 12-year-old summarized their views: “As an immigrant, Ellis Island symbolizes the main gate of entry of liberty and hope” (New York Daily News 2009).

Yet public perception of immigrants is mixed (Allport 1954; Buck et al. 2003). Support for immigrants is positively associated with the strength of the US economy, with greater support in times of economic growth and low unemployment (Espenshade and Hempstead 1996; Citrin et al. 1997; Espenshade 1997; Burns and Gimpel 2000; Haubert and Fussell 2006). On the individual level, those with less income and educational attainment are less likely to favor immigration (Chandler and Yung-mei 2001; Scheve and Slaughter 2001). Historical trends suggest that the public has become increasingly negative towards immigration, with a clear concern about levels of illegal immigration (Lapinski et al. 1997; Pantoja 2006; Schneider 2007).

Blumer posed a theory of symbolic interactionism, which states that social interactions are crucial in forming opinions of others (Stryker 1987). A recent meta-analysis of research using group contact theory to explain prejudice found that 93% of the studies concluded that contact lessens opposition to and prejudice against immigrants (Pettigrew and Tropp 2005). Yet some assert that intergroup contact increases animosity towards minority groups. For example, over 60 years ago, Key (1949) concluded that the concentration of African Americans at the community level was strongly related to Whites’ negative perceptions of that group. Similarly, other quantitative studies have echoed these findings (for a review see Forbes 1997).

There are reasons for a lack of consensus about the impact of intergroup contact. Perhaps there is a threshold beyond which interactions tip toward more understanding, and another threshold that tips toward more hostility. Some kinds of interaction likely are more critical than others. Hewstone et al. (2002) reported that a variety of factors may mitigate or influence contacts, including group size, perceptions of threats, and personality differences. Amin (2002) cautions against making simplistic assumptions and highlights the importance of factors such as social exclusion and ethnic isolation, insensitive policing, and institutional ignorance. Overall, there is a general consensus in the literature that interactions among different races and nationalities increase acceptance, but that consensus is not universally accepted.

In this economic and political environment, does it make sense to highlight the history of immigration that Ellis Island represents? Ellis Island is the rarest of public places, perhaps the most significant shrine to the promise and heartbreak of immigration in the United States. Ellis Island was the place that would turn back some 2% of those who made the voyage. Others became sick and died on Ellis Island. For this less fortunate group, Ellis Island was the “Island of Tears.” For the vast majority, Ellis Island was the place where they disembarked for resettlement and integration into society. Perhaps the United States’ response to the rehabilitation of Ellis Island, especially during a period when budgets are stressed, is a symbolic message about how the United States views immigration. The issue of immigration in today's context is the major reason I chose Ellis Island for a case study of cultural and historical artifacts.

A second reason for choosing this case study is local politics. New York and New Jersey were locked in a dispute about sovereignty over Ellis Island for over 150 years. The two states drew a line in the Hudson River, which gave New York jurisdiction over the original 3 acres that constituted Ellis Island. But more space was needed to receive additional immigrants, and fill was used to increase the island's size to 27.5 acres. With the island as a source of prestige and potential tourism revenue, the two states and their elected officials have exchanged verbal barbs. For example, during the early 1990s, Senator Frank Lautenberg of New Jersey had set aside funds to build a permanent bridge from New Jersey to Ellis Island (MacFarquhar 1995) located a quarter-mile away. His staff had estimated that 115,000 more people could visit the site if a permanent bridge existed. Nita Lowrey, a New York Congresswoman, contended that a permanent bridge would “seriously mar a great monument.” She called for all visits to occur by boat, the way the immigrants did. New Jersey officials responded that the Circle Line Company, stationed in New York City, was behind New York's opposition to the bridge. New York officials criticized New Jersey as a greedy latecomer that wanted the revenue from Ellis Island. New Jersey officials produced evidence that the President of Circle Line donated money to Senator Lautenberg's opponent in the senatorial election.

In 1998, the US Supreme Court settled the geographical turf issue by ruling, in a six-to-three decision, that the 1834 compact between the two states gave New York sovereignty over the original 3 acres, but that the remaining 24+ acres were granted to New Jersey (Shaw 1998). The EIS allows us to see if the New Jersey–New York tension has subsided in light of the threat to the South Island.

The third reason for focusing on Ellis Island is the degradation of the south side. The main building on the north side was restored and opened as a museum in 1990. The challenge of the EIS as a planning tool was to develop alternatives for the thirty buildings that were used for hospitals, quarantine, and similar activities. The planners must try to satisfy the surrounding states and cities as well as pro- and anti immigration groups, and their plans have to be affordable.

Ellis Island Development Program: the plan and EIS

History of the proposal

After the immigration function was discontinued in 1954, thirty vacant buildings (approximately 375,000 square feet) began to deteriorate. Federal, state, and private stakeholders pressed the NPS to at least temporarily stabilize the buildings and develop a plan that would rehabilitate the structures, expand tourist experiences, and provide sufficient economic resources to maintain the structures. The NPS responded with a short-term rehabilitation and stabilization program and a long-range plan captured in the Development Concept Plan (National Park Service 2005). The document drew heavily on earlier work that includes both the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. The NPS's general objectives were to protect Liberty Island's and Ellis Island's cultural, historical, and natural resources. Protecting these resources are the generic objectives of many cultural–historical rehabilitation site projects. The more detailed site-specific objectives for Ellis Island were to rehabilitate and reuse the island's award-winning Beaux Arts campus of integrated brick, stucco, and tile structures with connecting corridors of masonry and glass. As part of that effort, the NPS was to design a landscape of mature trees, grass, and other landscaping that would complement Ellis Island's historic themes. These structural and landscape designs were to reflect the island's special history and yet relate directly to contemporary migration, public health, and education. This combination of themes hopefully would garner public interest beyond the current museum and thereby attract financial and political support to limit reliance on governmental revenues.

To complicate this challenging assignment, in light of the terrorist attacks of 2001 at the World Trade Center a little over a mile away from Ellis Island, the NPS must control access to the island as a potential target and provide security for visitors, staff, and resources of the island. The NPS has to respond immediately to emergencies, which, in turn, required reconsideration of access and egress options.

In essence, the 2005 EIS analyzes three options.

No-action alternative

Option 1, the no-action alternative, would stabilize the vacant buildings and the temporary bridge to New Jersey. In essence, the no-action plan is a band-aid solution that the NPS has been implementing. The NPS would fully stabilize abandoned and unused buildings on the south side. In fact, much of this work had been completed when the EIS was published. The NPS uses temporary ventilated wood and plexiglass window panels to reduce water infiltration and increase air flow through the buildings. The original clay tiles are removed and temporarily replaced by asphalt shingle roofs. Stone and brick masonry is repaired, as are failing exterior or interior walls and weight-bearing structures. The corridors are cleared and repaired and the utilities are fixed to support minimal use. Gutters, leaders, and other repairs are made to control rain and snow melt. Vegetation damaging the structures is removed, and inside the buildings, debris and hazardous materials are hauled away.

This package of band-aid solutions, costing more than $50 million, is buying 10–15 years for a sustainable plan to be developed and implemented before the building deterioration becomes irreversible, requiring demolition. The general public would not be allowed in these no-action alternative stabilized structures. The no-action alternative solution requires maintenance of a security program, including the existing temporary construction bridge to New Jersey. When the temporary bridge is no longer functional, access will have to be by ferry or barge. In short, in 10–20 years the no-action option means the complete or almost complete loss of these thirty buildings. Should this occur, presumably the NPS or another organization at least will take photos to document the nations’ immigration history on these two islands.

Before summarizing alternatives 2 (day-only option) and 3 (day/night option), to avoid repetition, I summarize some elements common to both alternatives. Both preserve key south-side Ellis Island buildings and their surrounding environment, and provide options for economically sustainable adaptive reuse proposals. Both continue to rely on ferry boats by both day and overnight visitors. Given that the ferry trips are more expensive than a bridge from New Jersey, the EIS calls for subsidized ferry fares for low-income visitors and schoolchildren, reduced-fare days, and special passes. A third common element is construction of a permanent bridge from New Jersey that would be used for emergency response and evacuation; and for construction, maintenance, deliveries, and other operations. In the case of the preferred option (day/night), the bridge could be used to pick up and drop off conference center guests. Another commonality is infrastructure improvements to support the use of the thirty buildings and surrounding lands. Also, both alternatives require screening of visitors, packages, and vehicles, as well as capacity for emergency evacuations. The two alternatives also preclude several actions: deliberate demolition of any structures; construction of major new structures; reuse of buildings for dominant retail and/or commercial purposes; and pedestrian use of the service bridge. Lastly, both alternatives assume increases in the NPS budget for the island and from not-for-profit partners.

Preferred alternative: day and night use

The EIS preferred alternative is one that the NPS believes is most likely to be economically sustainable. The key element is an “Ellis Island Institute” that would be developed and managed by a nonprofit partner. The Institute would offer cultural and educational programs and activities. It would also include a policy research center.

Notably, a conference facility and overnight accommodations would be developed, financed, and managed by a professional hospitality business partner working with the nonprofit partner. The facility would host meetings, retreats, and workshops focusing on US immigration, world migration, public health, cultural and ethnic diversity, and family history.

A signature add-on of the preferred day/night alternative is the increased use of the site for overnight lodging and related facilities for conference participants. This option includes conferencing, internet and other communications, and other technological systems essential to make a such a facility competitive. The NPS has been working with Save Ellis Island, Inc. (SEI) to have this organization be the nonprofit partner for the implementation of the preferred alternative. Over $6 million was raised and used to restore the Ferry Building on the south island, which was reopened in April 2007. This preferred option would rehabilitate and reuse the twenty-nine other buildings over a 5-to 7-year period through a combination of government appropriations, private financing, and philanthropy. The preferred option rests on the assumption that a high-level facility focusing on migration, public health, and related topics located minutes away from lower Manhattan and northern New Jersey, and with a truly remarkable view of the entire New York harbor area, would attract visitors for day trips and conferences.

Second alternative: day use

This option does not provide for overnight accommodations or commercial office space. Yet office space for nonprofit organizations is part of this design. The plan calls for restoration of Ellis Island's historic buildings and landscape over a longer, 10–15-year period, using private fundraising efforts and federal appropriations. The NPS proposes a combination of partnerships, cooperators, and traditional concession operations to provide visitor services, programs, and maintenance of buildings. Building exteriors would be restored and interiors completed to “core and shell” condition. Tenants would provide interior finishes. NPS calls for preservation of one or more selected interior spaces left in “ruin-like” condition for future research and interpretation. Outdoor areas would be tied to the island's history. Visitor services would be provided through concession agreements.

EIS Elements

Table 3.1 (p. 64) lists the impact topics addressed in the final EIS.

The EIS did not consider the following impact topics because no impacts from the actions were expected: wetlands (none exist at the park); the 35,000-item museum collections; and environmental justice. The last of these three exclusions seems odd in light of the fact that access to the site via a bridge versus a ferry has been debated, and part of that debate is about poor people; the vast majority in this region are African American and Latino. Indeed, the topic is not ignored, but rather covered under access to Ellis Island.

Table 3.1 EIS elements in the Ellis Island study

Transportation |

Natural environment |

Built environment |

Indirect and cumulative |

Access to ferry terminals |

Marine sediments |

Historic architectural resources |

Hazardous materials |

Circulation |

Geologic resources and soil |

Archaeological resources |

Noise |

Access to Ellis Island |

Floodplainsa |

Cultural landscape |

Visitor experience |

Parking |

Fish |

|

Tourism |

|

Vegetation/threatened and endangered plants |

|

Administration |

|

Wildlife/threatened and endangered wildlife |

|

Ellis Island infrastructure |

|

Surface water |

|

|

|

Groundwater |

|

|

|

Air quality |

|

|

Preservation of historical architectural, cultural, and

associated marine resources

The no-action alternative clearly is different from the other two alternatives because it does not provide a plan to preserve Ellis Island's historical treasures. Many of the buildings on the National Register of Historic Places (National Register) would not be salvageable in 10–20 years. Options 2 and 3 preserve the historic properties.

In addition, the no-action alternative eventually results in the loss of the bridge connecting Ellis Island with New Jersey. Should there be a fire, older historic properties on Ellis Island surely would be at higher risk of fire damage before fire-fighting equipment could reach the island, unless a boat was used for fire fighting. The bridge proposed under the alternatives arguably limits the water use of the small water body between the island and the mainland (about a quarter mile).

The two preferred alternatives require digging into the terrestrial and marine environments, and could discover buried artifacts. Under the worst-case scenario, some of these would be destroyed or damaged.

Natural resources

Natural resource impacts are minor. The three alternatives require removing the bridge and closing the gap in the existing floodwall linking Liberty State Park to New Jersey. Marine sediments would be disturbed by removing the pilings in the current bridge, and the two preferred alternatives would disturb sediments when new pilings were added for a permanent bridge. The existing bridge – indeed, any new bridge under the two alternatives – could be flooded, and a bridge slightly increases the likelihood of flooding on the island.

On-site construction and adding a permanent bridge and access roads would disturb vegetation and add impervious cover. The island has several state-protected plant species that the analysts argue can be protected by avoiding them and replanting, if required. With regard to fish, removal of the bridge and building a new bridge would temporarily impede fish navigation, increase turbidity, and probably resuspend toxins now residing at the bottom of the channel. The construction would also temporarily impact wildlife, including a bird species protected by the State of New Jersey.

During construction, emissions and noise from construction equipment would increase, for longer under the two alternatives than for the no-action plan. If either of alternatives 2 or 3 is built, the analysts expect air emissions to increase 5%, a negligible change. Noise impacts are predicted to follow the same patterns, in other words, increases during construction and little impact thereafter. Overall, environmental resource impacts do not appear to be a major issue.

Social and economic resources

The expectation is that, under the no-action alternative, tourism at Ellis Island would increase slightly. Alternatives 2 and 3 are predicted to result in a benefit to tourism from more visitors to and around Ellis Island, as well as increased demand for lodging in northern New Jersey and Manhattan.

The report estimates that removing the current bridge could increase emergency response times up to tenfold, which could be a serious problem for someone requiring emergency services. A permanent bridge also would help site workers to cross from New Jersey. Without a bridge, ferry traffic would have to compensate, leading to more automobile traffic and parking at the ferry sites. Liberty State Park, where a permanent bridge would connect to the island, would experience more traffic and parking.

The analysts assert that the day/night alternative would substantially increase social benefits by increasing visitor access to more of the island's historical legacy, as well as the expansion of interpretive programming. The proposed conference facility with overnight lodging likely would result in a major benefit to some visitor experiences at Ellis Island. With the exception of overnight lodging accommodations, similar benefits to the visitor experience are predicted for the day-only option. In the short-run, visitors would notice more noise and traffic at the rehabilitated areas. Lastly, either of options 2 or 3 would require upgrading the utilities and infrastructure.

Overall, more than a half century after the immigration function ended, key parts of the Ellis Island legacy are essentially awaiting their fate. The NPS argues that “a window of opportunity exists – interim stabilization measures, combined with the determination of highly motivated nonprofit and governmental partners, have created the opportunity for what may be the last best chance to save these historic treasures” (National Park Service 2005, p. xiii). The authors of the EIS assert that their “plan honors the legacy of Ellis Island and sets the stage for the restoration and adaptive reuse of the entire historic immigration station complex” (ibid., p. xiii). The NPS considered reuse options that would stop deterioration of the thirty buildings and allow activities that are economically sustainable, and would not be perceived as turning over this unique part of US history to business interests for exploitation.

Doubtless, restoring the thirty buildings and landscaping would provide visitors with a snapshot of what this tiny city within its largest city did to welcome, screen, and care for millions of immigrants. The plan allows the reader to envision a place that would be more than another museum; stepping on Ellis Island immediately causes an emotional reaction for many Americans, creating a credible place to explore immigration in all its facets – racial and ethnic tolerance, civic responsibility, and provision of public health.

I have spent decades on projects to manage and destroy bombs and their wastes (Chapters 5 and 6). Hence my first reaction to the tables estimating the costs required to reuse Ellis Island was to discount the cost issue as trivial. I assumed the EIS controversy, if any, would be about how to reuse the site. But, after I read the EIS, I left persuaded that so much coalition building had already been done on the value of the legacy that dollars were the key issue. The $100 million plus are modest compared with government investments in support of every other project studied in this book. Yet the NPS is not the Department of Defense or Department of Energy, nor even the Department of Transportation, so the costs involved are high for the responsible government parties.

I characterize the presentation of costs of the three alternatives in this document as underwhelming. If the intent of the authors was only to provide general descriptions of the two options and the costs involved, then the document succeeded. The economic analyses in this “final” EIS are general sketches to accompany the concept plan. If option 2 or 3 materializes, the next supplemental EIS documents should be accompanied by clearer description of the conference center and proposed institute, including a substantial needs assessment, along with, I assume, a much deeper economic analysis. With about 310,000 square feet to redevelop, the EIS calls for about 85,000 square feet for education and interpretation. Option 2 (day only) calls for 225,000 square feet for non-for-profit institutional issues. Option 3 (day/night) discusses a 250-room and 225,000 square foot, high-end retreat and conference center, with 25,000 square feet of meeting space. The preferred day/night option is estimated to cost $169.5 million and the day option $178.1 million. The capital cost shortfall is $159 million for option 2 and $104 million for option 3. The shortfall for the preferred option is less because the hotel/conference center contributes almost $38 million in capital to the project.

The cost estimates are in year-2000 dollars, and the estimates of profit margin and borrowing rate assume practices and rates of that period, not the current period of much more constrained private dollars. It would be difficult to imagine building these projects for those dollars in the year 2010. Furthermore, the economic growth of northern New Jersey and New York City that began during the 1990s has ended. New Jersey and New York have lost hundreds of thousands of jobs as part of the loss of 3 million jobs in the United States in the year 2008. And losses have continued. Furthermore, there is a considerable excess of hotel and conference center space in the area. Current economic realities challenge the EIS options, especially the preferred one, as there are now fewer dollars and more competition for them.

While there is little evidence of New Jersey versus New York tension in the document, it could resurface. Competition for limited resources is part of my concern. More than a dozen projects are under way to rehabilitate and reuse sites that drain into New York Harbor. I cannot precisely estimate the costs of all of these because their plans are at various stages. The Statue of Liberty avoided this frenzy of competitive redevelopment by being redeveloped and reopened in 1986 for its bicentennial. When 9/11 occurred, the Statue of Liberty was closed, and the crown was not reopened for visits until July 4, 2009.

In addition to harbor-related projects, private and government capital has been used to help build new stadiums and/or infrastructure for the Yankees and Mets (baseball), Giants and Jets (football), and Devils (hockey), and one is being considered for the Nets (basketball) – this is in addition to stadiums for minor league teams and college arenas. None of these projects may be in direct competition for capital with Ellis Island. But in the current economic climate, I suspect that some are, at least indirectly.

Governors Island might be the most obvious competition. In 2008, the NPS released a 691-page final general management plan and EIS for Governors Island (National Park Service 2008). For over two centuries, Governors Island played a vital role in the defense of New York and New Jersey. During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Army placed artillery on the island to block the British from winning the war. After independence was achieved, Fort Jay, Castle William, and South Battery were built on Governors Island. These historical fortresses are what the NPS wants to preserve and feature. After the War of 1812, Governors Island was used to hold prisoners, by the military for recruitment, and as a prison (the northeast version of Fort Leavenworth and Alcatraz). The site was enlarged to 172 acres and became the largest US Coast Guard base.

In 2001 and 2003, Presidents Clinton and Bush certified the island as a National Monument. The EIS presents Governors Island as a place to feature coastal defense and ecology of the harbor. The capital and annual operating cost of the preferred project are, respectively, $50–60 million and $11–13 million. Are there financial resources for Ellis Island and Governors Island, as well as the other projects in the harbor? Will compromises be required that satisfy no-one? Will all or some of these projects be sacrificed in the current economic climate? Will this cause the New Jersey–New York rivalry to be rekindled?

Stakeholder reactions

The organization that will manage and sustain the Ellis Island dream will need internal cohesion. Accordingly, I read every written comment that was submitted to the NPS to attempt to assess support and concerns. The NPS created an interdisciplinary group to list and prioritize the issues, contact stakeholders, organize and conduct meetings, and obtain feedback. They relied on previous, 1995, EIS documents for the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island. Much of the information from the older EISs is directly applicable; the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks have required additional discussions about security and the need for a permanent bridge.

The NPS held three open meetings to scope out an EIS for the deteriorating areas. These were held in December 2000 on Ellis Island (sixteen attended), and in Trenton, New Jersey (thirteen attended) and Manhattan (fifteen attended). More than a dozen organizations expressed support for the preservation and reuse of Ellis Island during the December 2000 scoping sessions, including the New Jersey General Assembly, City of Jersey City, Liberty Science Center, New Jersey State Historic Preservation Officer, Governors Advisory Committee on the Preservation and Use of Ellis Island, Preservation New Jersey, New York Landmarks Conservancy, Liberty State Park Development Corporation, and the New Jersey Department of Health. On February 28, 2002, the NPS hosted a workshop on an Ellis Island Development Concept in New York City.

These meetings assisted in the preparation of the concept land-environmental impact statement of June 2003. Prior to the preparation of the document, the NPS followed routine EIS public notification protocols. The NPS and the EPA published a Notice of Intent in the Federal Register to prepare the environmental impact statement. Upon completion of the draft EIS, they published a Notice of Availability when the draft document was released for public review in May 2003. Letters were sent to the New York and New Jersey State Historic Preservation Officers, as well as the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation. Press releases or articles were published in local and regional newspapers. These publications include The New York Times, The Star-Ledger (Newark), and the Jersey Journal (primarily Hudson County). The executive summaries for the Development Concept Plan/Draft and Final Environmental Impact Statements were posted on the NPS website, and the draft and final documents were made available in their entirety on the NPS planning website.

During the 60-day review period of the draft document, the NPS held two open meetings to provide additional opportunities to comment on the document. The first of these was held on July 24, 2003 at Federal Hall in Manhattan, and was attended by fourteen people. The second meeting was held on July 28, 2003, at Jersey City University in Jersey City, New Jersey; it was attended by thirty-eight people. During the period of public comment on the draft EIS, letters, cards, and emails were submitted, in addition to written and verbal statements submitted at the public meetings. I found a list of organizations that participated during the scoping process and in response to the draft EIS. These included state government and their representatives, as would be expected. However, they also included individuals representing not-for-profits and for-profits, such as the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation, Advocates for New Jersey History, Circle Line Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Ferry, Inc., Guides Association of New York, Jersey City Office of Economic Development Liberty Science Center, Save Ellis Island Inc., National Trust for Historic Preservation, US Army Corps of Engineers, New York District, US Coast Guard, EPA, US Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, US Department of Transportation, and the Federal Highway Administration Historic Preservation Office. Overall, it appears to me that the NPS tried to obtain feedback from the two states directly involved, and from the surrounding local community in New Jersey. Not to have done so would probably have killed this project because of the political rivalry described above.

I briefly summarize some of comments to provide a flavor of what clearly was an extremely positive response to the EIS. The tone of the letters was positive, and most of the suggestions called for fine-tuning the ideas and coordinating with other responsible parties in the region. I saw no evidence of opposition to the two alternatives, and there was no support for the no-action alternative. Beginning at federal level, the Region II office of the EPA indicated that the EPA saw no significant adverse environmental impact. However, they would review site-specific documents for specific projects, such as the proposed permanent bridge.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation supported the opposition to a pedestrian bridge. The New York State historic preservation officer opposed public access via the proposed permanent bridge, and reiterated that New York State supported public access via ferries. New York's Landmarks Conservancy strongly supported the preferred alternative, and was very pleased to see that the idea of demolishing some of the buildings for new commercial use was not included. The Mayor of Jersey City supported the preferred alternative, and called for the NPS to reconsider the idea of a permanent bridge that would be accessible by pedestrians. Across the river in lower Manhattan, the Battery Park City Authority supported the two alternatives and called for following environmentally sustainable building practices.

The National Ethnic Coalition of Organizations Foundation (with headquarters in Manhattan) praised the document and requested a meeting to discuss how the rehabilitative facilities could be used to enhance ethnic harmony.

New Jersey's Commissioner of Environmental Protection supported the proposed alternative or other alternatives that would be economically feasible and sustainable. Representing New Jersey's Environmental Review group within the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection, a staff member provided a lengthy set of comments that, in essence, called for greater clarity about the proposals and interactions with the Department's permitting function and with the staff of adjacent Liberty State Park. For context, Liberty State Park is approximately 800 acres and over 2 million people visit it each year (see Figure 3.1).

The Liberty Science Center is a 200,000-square-foot museum located in Liberty State park in New Jersey. It offers educational programs for children. The President of the Liberty Science Center strongly supported the EIS concepts, and emphasized the need to coordinate closely with planning at Liberty State Park and Liberty Science Center (see Figure 3.1).

A group called “Friends of Liberty State Park” was extremely concerned about the continued presence of the road to the temporary bridge, calling it a “visual and physical intrusion” (National Park Service 2005, p. 230), and regarding it as in conflict with the Park's normal activities. They recommended limiting access to the bridge and tearing it down as soon as possible. The group is not opposed to a permanent bridge, as long as it doesn't cut through the park; in fact, they made a suggestion for a less intrusive location, and they do reiterate that a permanent bridge should allow pedestrians to walk to Ellis Island.

The Jersey City Department of Housing and Economic Development praised the plan and called for public access to Ellis Island via a permanent bridge. New Jersey's historic trust group called for carefully balancing public/private partnerships with public access and public use of the island. It commended the document for calling for discounted fares and special programs to bring low-income populations to the island.

Save Ellis Island, a not-for-profit organization, supported the concepts and emphasized the need to develop a transportation plan with Liberty State Park officials, as well as infrastructure plan for Ellis Island. Among the eighteen-member Board of Directors were five local elected officials and other prominent individuals from the surrounding areas of New Jersey. They expressed some concern about the accuracy of the cost estimates presented in the EIS. A faculty member from Jersey City State University, located a short distance from Ellis Island, strongly supported the idea of an Ellis Island Institute that would remind Americans of the importance of immigration. In his comments, Senator Robert Menendez of New Jersey supported the preferred alternative and characterized the no-action alternative as “a travesty. It would be the complete loss of thousands of stories of immigration” (National Park Service 2005, p. 254).

Interviews

John Hnedak is the Deputy Superintendent, Business Management, Planning and Development at the Statue of Liberty National Monument and Ellis Island. John was extraordinarily helpful, providing me with documents and suggestions. On July 27, 2009, I asked him questions about the project. He indicated that the EIS process was critical, and that the project as currently moving forward would not have been possible without the EIS process. The context for that statement is that, prior to the process that culminated in the year-2005 EIS, the NPS had tried to lease property on Ellis Island to a private developer under NPS-legislated authority to do so. The developer's proposal included extensive demolition of some of the historic structures as well as significant new construction. John noted that, as a result, the historic preservation communities of both New York and New Jersey voiced strong opposition to the project. Necessary compliance with national historic preservation requirements could not be achieved, and the project did not move forward. Members of Congress expressed concern over this result, and directed the NPS to continue planning for a project that benefited the public without demolitions or extensive new construction. The EIS represented the planning and environmental management tool that allowed planning to proceed. John Hnedak: “A project of this magnitude and importance is, by its nature, controversial enough to warrant the use of an EIS process to guide it. It allows us to systematically obtain input and support from the public and numerous communities of interest.”

John noted that plan is moving forward, although at a slower pace because of the recession. The Laundry Hospital Outbuilding is under rehabilitation by SEI. A great deal of progress has been made on the planning for seven of the buildings to be used primarily for historic interpretation. Most of these have been stabilized. All of the programming is designed for the public. He commended the Ellis Island Institute for their high-quality designs and educational programs. The Baggage and Dormitory Building, the largest, will be stabilized by the NPS with an $8.8 million grant from the American Recovery and Rehabilitation Act. The conference center is still part of the plan. The State of New Jersey has been very supportive with dollars and political efforts. The City and State of New York have been less active. John hopes for stronger movement on fundraising in a year or two.

Elizabeth Jeffery is Vice President, Planning and Capital Projects for the Ellis Island Institute and Save Ellis Island, Inc. Trained in design and urban development, Ms Jeffery had extensive experience in physical and business planning, and in housing and urban redevelopment, before assuming her role with the private arm of this government–private partnership to restore and adaptively reuse the historic buildings on the south side of Ellis Island. I spoke with her on September 2, 2009. Ms Jeffery described Save Ellis Island as the official partner for the rehabilitation and adaptive reuse of the twenty-nine unrestored buildings on Ellis Island. She pointed to two legal documents. On January 18, 2007, Save Ellis Island and the NPS entered into an agreement to provide for SEI's fundraising, planning, construction, and programming for the currently vacant and deteriorated buildings on Ellis Island's south side, comprised primarily of the Immigrant Hospital and the Baggage and Dormitory Building. Then, on June 19, 2009, they signed a Memorandum of Intent that described progress and decisions on the steps to fully establish the Ellis Island Institute as envisioned in the EIS described in this chapter. Ms Jeffery notes that the MOI also affirms the current federal commitments to the project.

Ms Jeffery characterized the EIS as a master and land-use plan, zoning document, and an assessment of environmental effects of implementing the plan. The document, she noted, does provide details because it was already dated when written and needed to be flexible. However, it was critical because the preferred alternative described by the EIS is the Ellis Island Institute and Conference Center. Also, the EIS decided upon a permanent operations bridge, new utilities, and no significant demolition or new construction – all of which were fundamental to the reuse plan.

She traced the founding of Save Ellis Island to the 1998 Supreme Court decision granting sovereignty to New Jersey of 22.5 acres of Ellis Island. Following the court decision, former New Jersey Governor Christine Todd Whitman established a commission to study the issue and make recommendations. The Report of the New Jersey commission was formally submitted to the NPS during the EIS public process. The Commission evolved into the 501(c)(3) nonprofit organization Save Ellis Island in 1999.

Ms Jeffery was very clear about the role of the EIS. The EIS represents a “snapshot in time,” she noted, and as such should not be overly proscriptive, because a great deal of analysis is required to design the best combination of land uses and activities. The EIS finished its public process in 2002 with very few objections or comments. Nevertheless, it took 5 years for it to be approved and published in the Federal Register. That delay was costly. Save Ellis Island was not able to obtain federal approval for the project, so fundraising was nearly impossible. In addition, several strong markets and an overall active philanthropic climate were missed. Apprehension and overly cautious attitudes at the NPS also delayed implementation. The EIS helped bring together interested parties, increased awareness, established the basic parameters for the project, and helped establish inter-governmental and inter-agency communication at the beginning. Due to its iconic stature, having public input on the planning for this site is important.

She concluded that establishing the basic plan and approving the fundamental elements of that plan were critical. For example, a major reduction of available space or a significant new requirement could have made that complex and challenging project unfeasible. Also, an EIS proactively addressed and took conclusive actions regarding the bridge and other contentious issues, which was important because, if a project were subject to constant revision and inconsistent requirements, it would be impossible to finish.

Ms Jeffery suggested that the EIS was a legal foundation for Save Ellis Island and the NPS to develop and begin implementing their ambitious plan (Save Ellis Island 2006, 2007, 2009; see www.saveellisisland.org for updates). The Mission, Goals and Vision document begins with Emma Lazarus's (1883) often-read, moving poem:

. . . “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

(Save Ellis Island 2006, p. 1)

The document points out that almost 10% of immigrants who came through Ellis Island arrived sick:

When 2 million people each year visit the Ellis Island Immigration Museum in the restored Registry Building to pay tribute to this immigration story, they miss the story of the other Ellis Island – an evocative complex of hospital buildings where the sick were treated with compassion and America's public health was protected. This is the story of the “other” Ellis Island – a story that powerfully resonates today as once again we confront global health issues and the massive migrations of people around the world. This is the story that “Save Ellis Island” is mandated to communicate and preserve, through the rehabilitation and re-use of 30 historic buildings that sit nestled in a park-like setting on the south side of Ellis Island, with a dramatic view of the Statue of Liberty and Manhattan – so near and yet so far for the immigrants who were too sick to enter the country.

(ibid., p. 2)

The document describes this partnership with the NPS as “one of the largest historic preservation projects in America” (ibid., p. 2), and adds that the project will “further public understanding of the global migrations of peoples and the importance of health and well-being for the human community” and “demonstrates the economic and social benefit of historic preservation for civil society, and the relevance of historic places in the twenty-first century.”

In light of the criticism of EISs as not collaborative, Ms Jeffery pointed to the objectives of this partnership. Save Ellis Island expects the two partners to build relationships with government agencies such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the US Public Health Service, the US Citizenship and Immigration Services, and state and local departments of public health, to raise the profile and reputation of the Institute and enable it to reach broader audiences, as will partnerships with NGOs and policy institutes such as Doctors Without Borders, the Pan American Health Organization, the Urban Institute, and the Migration Policy Institute. Partnerships with health corporations, including those in the pharmaceutical field and other medical-related businesses, will increase the Institute's visibility in the corporate world, both as a source of support and as an audience for Institute conferences and programs. Ethnic organizations will be solid partners for the Institute, including those that represent current immigrant groups and those representing smaller and lesser-known immigrant populations.

The Institute will be an educational institution in the broadest sense, and its partnerships with formal educational institutions will be paramount. The Institute has already established a robust program for school teachers in grades K–12, and will expand this partnership to engage community colleges, universities, schools of public health, graduate programs in historic preservation, and scholarly professional organizations with compatible missions. Through these strategic partnerships, the Ellis Island Institute will construct a local, regional, national and international presence and reputation for sound, quality programs, known and respected in the fields of migration and public health.

(ibid., p. 12)

Perhaps because of her background in planning and design, Elizabeth Jeffery has a clear concept of the role of the EIS in a public–private partnership. The EIS is the flexible conceptual master plan that provides legal authority for action. The EIS allows the partners to move forward with a program that requires modifications that cannot be captured in a single EIS. She views partnership with the NPS as an effective way of overcoming the tendency of government bureaucracy to be overly cautious and afraid to make mistakes, and to drag its feet. Save Ellis Island has been able to raise over $40 million for restoration work and development of educational programs. Elizabeth noted that Save Ellis Island was moving more slowly than a private company might, but the EIS and government partnership provide fundamental principles and certainty on what can be done and allow the not-for-profit partner to be proactive.

My third interview was not a single conversation, but rather the summation of a number of contacts during the past five years and media reports. Senator Robert Menendez of New Jersey has been an outspoken proponent of redeveloping Ellis Island. The fact that the EIS was strongly supported provided Senator Menendez with an opportunity to attract the attention of Ken Salazar, who had been nominated as Secretary of the Interior by President Obama. The Department of the Interior has 60,000 assets and a $9 billion backlog in deferred maintenance (Hennelly 2009). Even a good, widely supported project could get lost in this backlog. At Salazar's confirmation hearing, Senator Menendez raised the issues of the Statute of Liberty and Ellis Island, and the nominee promised that he would visit. The first formal visit of the new Secretary was to the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island.

Senator Menendez remarked:

Secretary Salazar showed that he is a man of his word by visiting the national treasures a week after he committed to me during his confirmation hearing that he would do so. It's one thing to listen to the arguments for why we should reopen these national treasures from afar, but it's another thing to be here in person, where you can fully appreciate what an unrestricted visit to these landmarks means to all of us Americans. It really has an impact on you and your sense of country. We climbed to the top of Lady Liberty's crown, where I helped make the case that it should be reopened – it's a very moving and powerful setting in which to have that discussion. On Ellis Island it was clear that the Secretary was moved by our visit to the dilapidated buildings which remain closed and the history that they hold within their walls. The Secretary must now make sure he does a thorough examination into the reopening and restoration process, and he has some further information to gather. I am optimistic that he will look for a management solution that allows Lady Liberty's crown to reopen while ensuring the safety of its visitors. I am also optimistic that he will look for the ability within his upcoming budgets to help complete the full restoration of Ellis Island.

(Save Ellis Island 2009, p. 1)

When interviewed by a radio reporter, the Secretary remarked: “As we look at the economic recovery effort for the nation President Obama and the members of Congress are looking at, certainly places like this ought to be primary candidates to be able to fund to get those jobs going” (Hennelly 2009).

Evaluation of the five questions

Information

I am familiar with the waters of the New Harbor from water quality studies, and have visited and studied the land forms on and surrounding Ellis Island. There are no major holes in the environmental resources database. Some of the descriptions (such as noise impacts) are thin, but the estimates seem reasonable. In fact, these are not major issues. The most serious shortcoming I found is the limited economic analyses. As someone who has worked on and critiqued economic impact and life-cycle studies, it is not unusual for me to conclude that I want more information. This economic presentation is so limited that it lacks credibility – it truly fits the expression “back-of-the-envelope calculations.”

Another gap is the non-monetary values of the historical structures and artifacts on the island. The descriptions of the structures might as well have been taken from an encyclopedia. With all due respect to the NPS and the writers of this report, the descriptions are boring and the photos too limited. I understand and teach the value of scientific objectivity. However, the emotions that Ellis Island stirs for many of us are not conveyed. I would argue that scientific objectivity would have survived several well-placed quotations or stories told by people who landed on the island. These could have been woven into the presentation as side bars.

Another shortcoming is evacuation and emergency response. The two preferred options include a permanent bridge. Part of the justification is emergency response. The data offered to justify this addition are limited. Could people not be evacuated by fast-moving ferries, police boats, or other fast-moving vehicles? Could terrorists not attack via a permanent bridge, which they could then demolish? There may be good answers to these questions. But the questions were not raised in the document, which seems a surprising omission for this location – a short distance from the former World Trade Center towers.

The tone and writing are appropriate for a general audience. The evidence presented favors the preferred option. However, none of the options is dismissed out of hand, including the no-action option.

Comprehensiveness

The document includes cultural, environmental, economic, historical, and social considerations, emphasizing the cultural/historical legacy of the site. It certainly is comprehensive in evaluating individual categories of potential impacts. I would have liked to have seen an analysis of the cumulative impacts of the Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island, and Governors Island, and of the combination of Ellis Island, Liberty State Park, and the Liberty Science Center. In general, I believe that the cumulative social and economic effects of these sites as combined packages are greater than those of any one individual project. In particular, the combination of Ellis Island, Liberty State Park, and the Liberty Science Center would likely provide greater justification for a permanent bridge than just Ellis Island.

Coordination

The NPS contacted other federal agencies, and state and local governments. If there is a missing ingredient, it is the NPS expressing its big picture. I do not understand why the NPS plans for all the sites in the area are not provided in sufficient detail to help the reader understand how Ellis Island fits in with Governors Island and others. If there is no overall design, then that should be stated. If there is one that is detailed elsewhere, it should be described. Notably, the Governors Island EIS is more forthcoming about all the projects in the region, but not much more. This shortcoming left me to infer that this is part of the history of lack of cooperation between New York and New Jersey.

Accessibility to other stakeholders

The NEPA process provided multiple venues to input values and suggestions at locations in Trenton, Ellis Island, and lower Manhattan, as well as through the mail. The responses were from senior elected officials, government staff, and representatives of not-for-profit organizations. Few individual citizens submitted testimony. This result has to be a slight disappointment to the NPS. A large number of letters from residents of Jersey City, teachers, and other potential visitors would have made a stronger statement to the elected officials who control the dollars.

Fate without an EIS

There is so much support for this project from immigrant groups, Save Ellis Island and the State of New Jersey that a program would be under way without an EIS. But what kind of a program? And what kind of final objectives? It is hard to be certain that, absent the EIS process, the final land-use decisions would have benefited the public. That is, I have too often seen historically notable land uses across the United States demolished or retrofitted for profit-making endeavors such as gambling casinos, sports arenas, parking lots, and a host of others. The EIS functioned as a planning and organizing tool that gave stakeholders access to the process, and the decision-makers the legal authority to control land uses. The EIS requirement was the security blanket for the south side of the island, protecting it from profit-making abuse. The downside of this EIS is that it has taken a long time to implement the process. Arguably, without a formal EIS process, elected officials could have been persuaded to set aside the resources for the project and to worry about the impacts later. Certainly, the timing of the project has hurt fundraising. However, I suspect that the project would have run into legal challenges without the EIS process, and, as noted above, the preferred alternative could have been set aside without the process. I conclude that the NPS successfully adapted the EIS process to the needs of this widely supported, public-oriented, historical–cultural project.