| 2 | Metropolitan New Jersey: transportation, sprawl and urban revitalization |

Introduction

The end of the Second World War released pent-up demand for new housing in the United States. Fishman (2000) describes how government housing programs, new highways, and other government programs promoted suburban development. Deindustrialization and then civil unrest of the 1960s increased middle-class suburbanization. Post-war transportation increasingly became automobile-oriented. Rates of car ownership doubled, or more, in major American cities such as Boston, Denver, Detroit, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and even mass-transit-oriented New York City. Automobile use increased even more in the newly formed auto-dependent suburbs (Roberts 1999).

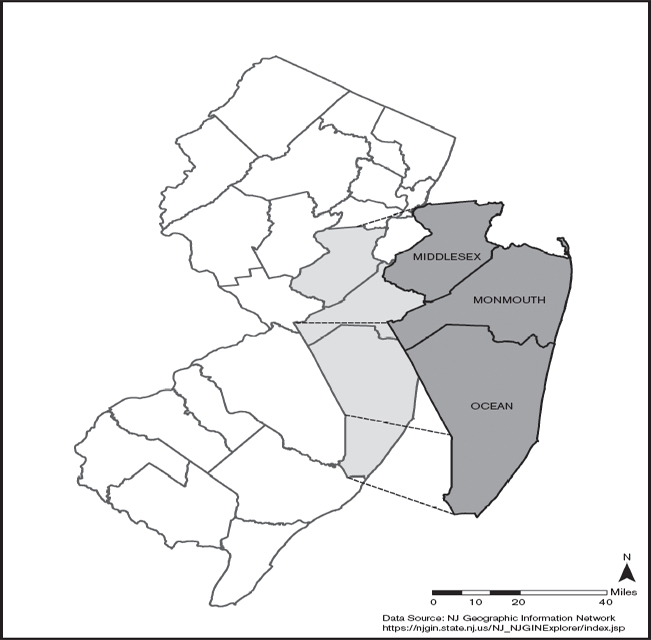

Between 1950 and 1970, California, Florida, and New York experienced the largest relative population increases, and some of their older industrial neighborhoods declined. Yet the author believes that New Jersey was the poster child for the negative impacts of auto-oriented suburbanization and industrial erosion. With a population of 1200 people per square mile, New Jersey has the highest population density. Indeed, it is the only state in the United States with a population density exceeding 1000 per square mile. Between 1950 and 1970, the “Garden State's” population increased by 2.3 million people, the sixth largest proportional increase of any state in the United States. Suburban Burlington (Philadelphia suburb) and Middlesex, Monmouth, and Ocean counties (New York City suburbs) grew by more than 40%. Ocean County's population (see Figure 2.1) increased 93% between 1960 and 1970, the largest increase of any metropolitan county in the United States during that decade.

Locations of Middlesex, Monmouth, and Ocean Counties, New Jersey

Compounding the increase of commuter automobile traffic in this densely populated region, many residents of New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania have taken their summer vacations along the New Jersey Atlantic Ocean shore (see Figure 2.1). Driving to the New Jersey shore from New York City, Philadelphia, their suburbs, and northern New Jersey became a time-consuming and grinding experience.

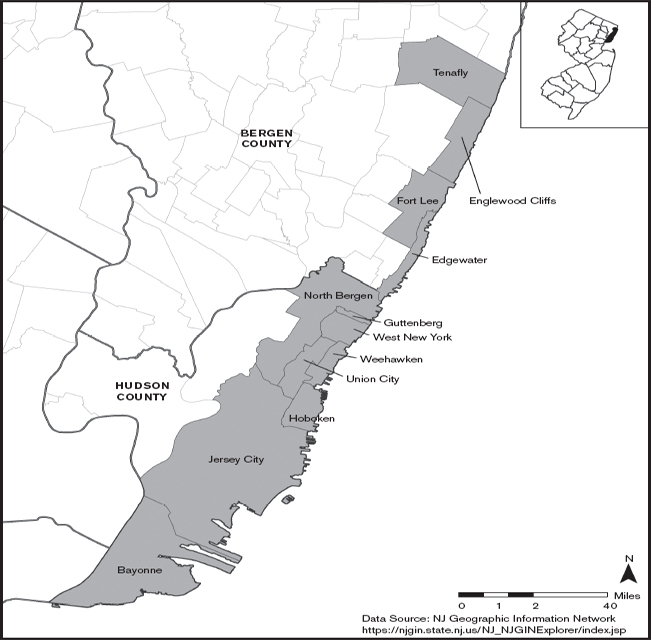

After the Second World War, New Jersey had the highest proportion of its labor force in manufacturing jobs. But as these jobs gradually disappeared from cities, Hudson and Essex counties (see Figure 2.2, Essex is located directly west of the Hudson), two densely developed, industrial-oriented counties lost population, industrial, and commercial jobs. Many new roads were proposed as essential to revitalizing these cities.

In short, during the late 1950s and 1960s, building more roads and widening existing ones seemed like a straightforward solution to managing increasing traffic congestion and revitalizing cities. Yet, by the 1970s, the undesirable environmental consequences of the road building remedy became obvious. Oxides of nitrogen and photochemical smog, produced by automobile engines, increased. The national ambient air-quality standard for ozone was exceeded in many places in the United States, more so in New Jersey than other states; nineteen of the twenty-one New Jersey counties exceeded the standard. During the summer, a brown haze formed and drifted hundreds of miles from the Philadelphia suburbs through New Jersey and New York State into Massachusetts, Vermont, and elsewhere in New England. The smog hung over farms, forests, and other rural areas, frustrating many people and violating the newly promulgated national air-quality standards.

Highway-associated site and sound problems became increasingly obvious. New highways brought disruptive noise to formerly quiet neighborhoods. Some viable communities were destroyed by new roads and widening of roads. People accustomed to walking to visit their friends a few blocks away were separated by six-lane roads. Open space in cities, as well as in suburbs, was lost, and the toll on animals, plants, and ecosystems grew. Most distressing to transportation planners was that new highways did not seem to reduce traffic. Instead, more highways seemed to generate even more traffic.

In a study for the state of New Jersey, Burchell et al. (2002) have documented the economic and psychosocial costs of unmanaged sprawl experienced by California, Florida, and many other states, including and perhaps especially New Jersey. One cost was that more investment was required in new suburban areas for schools, police, fire, water and sewer systems, and other services. While new schools were being built in suburbs, schools in many cities and older suburbs deteriorated and were closed when their population declined. Hence the second part of the economic penalty of unmanaged suburbanization was the increasing abandonment of sunken investments in cities and older suburbs. Burchell et al. (2000) estimated that a continuation of the suburban-oriented recent land-use trends in the state would require additional annual infrastructure and service costs of approximately $418 million (about $55 per capita). By instituting moderate efforts to control suburbanization, the additional annual deficit would be reduced to $257 million, or $160 million less.

New Jersey's “Gold Coast”

Focusing on two New Jersey transportation projects, this chapter considers the impacts of rapid post-Second World War suburbanization and urban decline, especially the environmental impacts. More specifically, I examine how the environmental impact process intersected with policies, first to defeat more highways, and then to choose among mass transit proposals. The two EIS processes presented here represent uses of the EIS process to manage transportation-related environmental decisions; and, secondarily and strikingly, the adaptation of the EIS process to the realities of the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. The reader will see two documents that are remarkably different, especially with regard to public participation.

New Jersey offers numerous illustrations of the rejection of highway proposals. I found forty-six highway projects in New Jersey that were canceled or modified between the early 1970s and the early twenty-first century. Nearly all of these rejections occurred before 1980. They were located in every county, and a number crossed into New York and Pennsylvania. They ranged from small, unfinished segments of existing highways to new 50-plus-mile four- and six-lane roads. The three major reasons I could find for their defeat were increasing costs, local public opposition, and environmental requirements. From among these failed proposals, I selected the Alfred E. Driscoll Expressway, which was bitterly contested, with environmental concerns at the forefront of the debate. With regard to mass transit, proposals for light rail systems, monorails, and other mass transit people-movers have blossomed. Three light rail systems were constructed in New Jersey: Hudson–Bergen, Newark, and the River line. While each offered interesting environmental and political challenges, I picked the Hudson–Bergen Light Rail, which involved lengthy debates.

I believe that the EIA process highlighted the problems associated with highway projects and the advantages of mass transit. The New Jersey Department of Transportation stopped at least six of the forty-six failed projects because of the need to prepare an EIS. State officials concluded that serious environmental impacts could not be avoided. For example, some proposed routes would have passed through the environmentally sensitive Pine Barrens in southern New Jersey, now a large protected ecological preserve with dwarf pine trees and other uncommon ecosystems. Other projects would have passed through the New Jersey Meadowlands, another unusual ecological system, a part of which contains the football stadium of the Giants and Jets. Other highway proposals would have encroached on the Passaic Falls, where Alexander Hamilton planned the first American manufacturing center. And still other projects would have required building a new bridge across the Hudson River on the majestic Palisades scarp that is visible from the George Washington Bridge.

I am not saying that no new highways were built after NEPA was passed; rather that there clearly was a major scaling back of highway projects after the passage of NEPA. Increasing public concern about the environment made highway projects politically vulnerable when their EISs were scrutinized. Elected officials and citizen groups quickly recognized that they could use the NEPA requirement to make their case for preserving open space and historical facilities, and for pressing both anti-sprawl and highway agendas.

It was feasible to design engineering solutions to some of these environmental problems, but the engineered solutions made some highway projects too expensive. Also, some of the proposed projects defeated in New Jersey would have been blatant examples of environmental injustice, destroying city neighborhoods occupied largely by poor, minority populations. Although the expression “environmental injustice” did not become part of the common lexicon until the late 1980s, critiques of highway proposals showed how they disproportionately impacted poor neighborhoods. In short, the EIS process clearly helped inform decision-making, providing information to support arguments against many highway proposals.

A good deal of the public, and many powerful elected officials, turned against building more roads and increasingly toward mass transit. In 1972, New Jersey's voters defeated a $650 million transportation bond issue that emphasized highway construction. And again, in 1974 and 1975, a combination of commuter groups and environmental organizations worked actively to defeat highway-oriented transportation bond issues in New Jersey (Sullivan 1979). When Brendan Byrne became Governor of New Jersey in 1974, his platform emphasized improvements in mass transportation and opposition to highways.

Among the numerous road and rail projects in New Jersey, I have picked two that illustrate the role of the EIS in highlighting the abrupt change in public perception of new highways, and the interesting role of the EIS in the process of underscoring this change.

The Alfred E. Driscoll Expressway: proposal and decision

History of the proposal

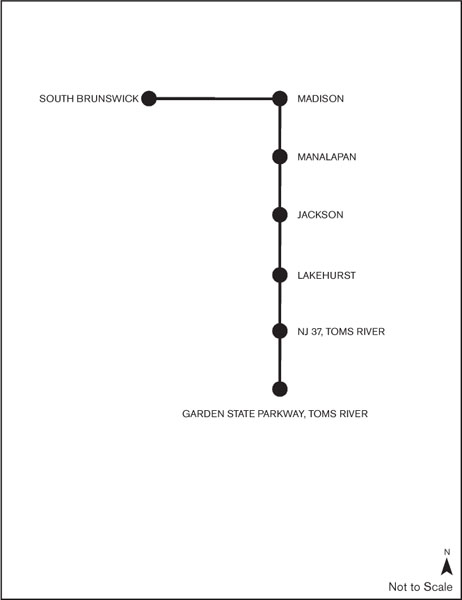

In 1964, the New Jersey Highway Authority, the then operators of the Garden State Parkway, proposed a 45-mile-long expressway, the Garden State Thruway, linking Woodbridge in Middlesex County, New Jersey with Toms River in Ocean County (see Figure 2.1). This thruway, to be open to all vehicles, including trucks, was to provide a bypass of the Garden State Parkway (no trucks allowed on the northern part of the highway) and US9 (slow traffic with many traffic lights) through the interior of the state. Along with an east– west highway, this northwest-to-southeast toll road was part of the so-called “Central Jersey Expressway System” between New York City and Philadelphia. The New Jersey Highway Authority already had purchased 253 acres along the proposed route. Plans for the Garden State Thruway were on official maps through much of the 1970s. However, noting financial cost concerns, the New Jersey Highway Authority decided against building the Garden State Thruway.

In October 1970, the New Jersey Turnpike Authority took over the project and changed it in several important respects. In 1971, the Authority proposed a 36-mile-long, four-lane toll expressway from the New Jersey Turnpike in South Brunswick (Middlesex County) to the Garden State Parkway in Toms River. The name was to be the Alfred E. Driscoll Expressway, after the governor who opened the New Jersey Turnpike.

The Driscoll Expressway was to provide a high-speed corridor for central and southern New Jersey, and notably was to provide access to trucks. The $1.2 billion expressway (dollars inflated to the year 2010 by author) was to be financed by New Jersey Turnpike Authority bonds. The Driscoll Expressway was to open in 1976 and to carry approximately 40,000 vehicles per day (annual average daily traffic, AADT). While its construction would have required the displacement of eighty-four homes and six businesses (see EIS discussion below for details), the expressway (in conjunction with appropriate planning and land-use controls) was expected to accommodate residential, commercial, and light industrial growth more effectively than the existing set of highways. Lapolla and Suszka's (2005) book about the New Jersey Turnpike characterized the road as “an extension of the Turnpike's beautification program” (p. 99). Readers who have driven along the New Jersey Turnpike would be hard pressed to describe it as “beautiful.” Hence characterizing the new road as an effort to extend beautification, frankly, lacks credibility. I will try to put this observation in perspective in the following section.

Design concepts

Architects and engineers had learned from negative reactions to the New Jersey Turnpike's long and straight lanes and lack of any semblance of aesthetic values that the public wanted something more visually appealing. Hence, while the plan had some of the corridor-like efficiency of the Turnpike, the Alfred E. Driscoll Expressway was designed to include aesthetic values that were consistent with the increasing interest in environmental protection of the early 1970s. For example, the Driscoll Expressway was to have a median that preserved existing vegetation. Landscaping along rights-of-way and center medians was to reduce noise from the road and make it appear greener and less gray. A greenbelt along the Expressway's 450-foot-wide right-of-way to enhance the environment reinforced this objective. In addition, the road was to have controlled access at interchanges spaced miles apart. Interchanges were to be constructed at seven locations along the 36-mile road (Figure 2.3).

The highway was to have 12-foot-wide traffic lanes, 12-foot-wide shoulders, and 1200-foot-long acceleration and deceleration lanes. All grades were to be kept to a maximum of 3% to increase safety and improve appearance, and all curves were to have a minimum radius of 3000 feet. The expressway was designed for 70 mph, yet the legal speed limit of 60 mph was established to allow for a margin of safety. In addition to these design standards for the roadway, there were also specifications established for all turnpike structures, including bridges and storm-drainage facilities. In other words, compared with the exceeding linear, undecorated, and dreary-looking New Jersey Turnpike, the Driscoll Expressway was to be less visually offensive.

Exits on proposed highway

The environmental impact statement

In May 1972, the New Jersey Turnpike Authority hired a team of four expert consulting groups to evaluate the potential environmental impacts of the proposed Driscoll Expressway. New Jersey's guidelines for EISs called for the experts to “provide the information needed to evaluate the effects of a proposed project on the environment” (State of New Jersey 1972; New York Times 1973a). In September 1972, the team submitted a 250+ page report (New Jersey Turnpike Authority 1972). That EIS, consistent with that period, is relatively short and not equivocal about issues.

Before highlighting some of the details, note that the document's conclusion is that the “completed expressway will provide a pleasing, functional and economically sound addition to the southeastern part of New Jersey” (ibid., p. i.) The authors add:

The need for additional access to serve commercial, passenger and mass transit traffic has been apparent for many years. Intolerable congestion, stop-and-go traffic and unconscionable delays have been too typical of May–October travel. This situation now extends to virtually an all-year travel pattern.

(ibid., p. ii)

The firm of Howard, Needles, Tammen & Bergendoff described the project and reviewed alternatives, including the no-action alternative, any probable adverse environmental effects that could not be avoided, and steps to minimize environmental effects. They noted some visual aesthetic impacts of the proposed road, especially during construction. They also mentioned rights-of-way and fences, but that these would be obscured by landscaping. They lauded the idea of a green central median. They pointed to no major positive or negative impacts on man-made resources, nor did they identify negative impacts on the health, safety, or well-being of the public. They pointed out that seventy-three homes and eleven mobile homes would be displaced, along with six active businesses. With regard to health and safety, they noted that the Expressway was designed to minimize long, straight stretches of the roadway, and that rest areas would be provided for driving breaks, as well as emergency services to assist injured people and disabled cars. The consultant concluded that accident rate would be much lower than for the roads currently carrying the traffic to that part of New Jersey, in fact, about a quarter of the rate for traffic headed in the same direction on existing roads.

Bolt, Beranek and Newman, Inc. evaluated noise impacts. They estimated that a total of twenty-five residences, including ten mobile homes and fifteen scattered houses, would be impacted, and that 15% of three parks and recreation areas would be affected by the road traffic. The company pointed to schools, including Manalapan High School, which would be affected, but noted that noise barriers would be built to eliminate the impacts. Notably, they emphasized that noise levels in the area as a whole would be reduced by, on average, 4–5 decibels (dBA) by transferring traffic, especially trucks, from existing roads to the Driscoll Expressway. In my opinion, this was the best known noise-impact consulting firm in the nation at this time.

Coverdale & Colpitts, Inc. reviewed socioeconomic impacts. Their review is remarkable for its long list of positive impacts and no negative ones. For example, the proposed road would relieve summer peak-hour congestion, provide access to trucks, improve highway safety by diverting vehicles from existing roads, decrease vehicle-operating costs, improve prospects for better commuter-bus services, increase land values and thereby tax bases, and attract new light industry and commercial facilities as well as new residential growth. Their evaluations suggest that more land would be committed to permanent open green space and that, while a small portion of viable farms might be affected, many other farms would be converted to higher-value end uses. Any negative impacts, they concluded, could be managed by applying local zoning and other ordinances and by proper enforcement of regulations.

Environmental Research & Technology, assisted by other firms, examined air quality, water resources, other natural resources, and social and physical resource impacts. No adverse environmental impacts on air quality were noted, nor any on water resources. The authors point out that the route requires several rivers to be crossed and that some parks would be crossed, but that these crossings, and wetland fillings, would be done without damage by following proper practices. Invoking a “two wrongs make a right” argument, they noted that the processes used for the highway would be less destructive than those for other developments in the area. They did identify potential impacts on cranberry bogs in the state, and once again emphasized that these problems could be prevented by proper design and construction.

With regard to social and physical resources, their report shows no major adverse environmental impacts; rather, they stated that impacts could be addressed by design and construction. They pointed to positive impacts on some public facilities that would become more accessible and defined. They also described why some route alternatives were not recommended, almost always citing incompatibility with local plans.

The no-project plan was described as follows:

A decision not to build the Governor Alfred E. Driscoll Expressway would mean a continuance of the existing inconvenience to local highway users, an increased . . . inconvenience to vacationers traveling to south shore towns, an intensification of traffic congestion and the ignoring of master plans prepared by affected municipalities and counties.

. . . A decision not to construct the Alfred E. Driscoll Expressway would waste the efforts of the affected municipalities and counties to shape desirable future regional development patterns, protect existing and potential county parks, road and correctional facilities and protect local patterns of development.

(ibid., pp. 17–18)

As noted above, this document in particular, like many of that early period, did not devote a great deal of space to equivocation.

Conflict and rejection

The Driscoll Expressway was approved by the New Jersey State Legislature in 1972, and the EIS was prepared and submitted in September 1972 (see below). Public hearings began shortly thereafter along the proposed route, and sixteen alternatives were considered.

Local community groups raised major objections during these hearings. Their concerns were about noise, added traffic, possible air pollution, and harm to the New Jersey Pine Barrens, a unique ecological system in central and southern parts of the state. For example, on November 26, 1972, residents of suburban Manalapan Township criticized the proposal, focusing on the design that indicated it would pass within 200 feet of an elementary school and would require removing twenty-three homes (Cheslow 1972). On December 15, a meeting in Toms River brought out some proponents but many more opponents (New York Times 1972). Again, this kind of public reaction to early EISs was common.

Yet the Turnpike Authority did not yield. It countered the opposition, and Wall Street immediately purchased $210 million of the bonds within a few days to fund the highway (Dawson 1973). In September 1973, the Turnpike Authority met with mayors of four municipalities who pressed for modifications in the alignment (New York Times 1973a). In November, the Turnpike Authority awarded the first contract for the expressway (New York Times 1973b).

But less than a month later, Governor Brendan Byrne opposed the highway as a “danger to the environment and [because] the fuel shortage had reduced the need for the road” (Sullivan 1973). Yet, having spent $20 million in design and engineering, a day later the Turnpike Authority contested the Governor elect's opposition (Waggoner 1973a). Former governor Alfred E. Driscoll, chair of the New Jersey Turnpike Authority, asserted that former Governor William T. Cahill had approved the highway and that his successor did not have the authority to reverse that decision. But, on December 28, 1973, plans to award any additional contracts were postponed (Waggoner 1973b).

Six months later, a three-judge appeals panel supported the opposition, criticizing the authority for misleading the public about the route (Sullivan 1974). Governor Byrne was criticized by construction workers (Janson 1974) and investors (Phalon 1975), and was asked not to attend the funeral of former governor Driscoll (Sullivan 1975). A week after governor Driscoll died in March 1975, the New Jersey Turnpike Authority officially dropped its plans for the Driscoll Expressway. During the late 1980s, the Expressway rights-of-way were sold.

Interview with former governor Brendan Byrne

Brendan Byrne was Governor of New Jersey from 1974 to 1982. I had spoken to him about various environmental and public health issues during the years. Consequently, when I called him on July 17, 2009, he immediately understood the purpose of my book and got right to the point. He made two major points. The former governor recognized the legal and political significance of NEPA, especially in the 1970s, when the Driscoll Expressway was proposed, and he supported the idea of comprehensively analyzing environmental and social impacts. Yet his reaction to this proposal, which I quote below, illustrates that asking the right questions does not necessarily lead to answers that decision-makers support, especially when the EIS, frankly, does not seem to consider the full range of viewpoints and data. Governor Byrne said:

I made a political decision based on gut feeling and advice. A lot of what a governor does is based on a gut feeling. I concluded that the Expressway would've led to the [New Jersey] shore being swamped by developers and tourists. One local official, who was against, said that the Expressway would have led to the paving over of Ocean County. State Senator John Russo, who has strong environmental credentials, supported my position at the time. The Expressway was not a major political issue. The EIS did not convince any of us to support the Expressway. I just was against it, and I had good reasons for my opposition. I never regretted the decision.

Governor Brendan Byrne, I believe, because of his political sophistication and understanding of the entire state, had a more nuanced and I would say accurate understanding of the cumulative impacts of this proposed express-way than the supporters of the highway and those who prepared the EIS. If a different person had been Governor of New Jersey at that time, there was a good chance that the Driscoll Expressway would have been built. Governor Byrne did what most elected officials will not do, which is to overrule a high-priority project of a cabinet-level agency (see Chapter 7 for another example).

Evaluation of the five questions

Information

The information presented in the document appears to this author to be based on appropriate science and engineering. For example, the noise experts were arguably from the best noise-pollution company in the United States, and they identified places where decibel levels would cause public reaction. From reading the EIS, I cannot see a single location where the noise analysis was improperly done. Yet there are several inexplicable holes in the information, most notably the impact on open space. Although I admit I have not surveyed the area, the open space analysis seems perfunctory, but I may be wrong. Unfortunately, given the period when this document was prepared, I cannot locate any documents or people who can testify to the thoroughness of the open space analysis.

The most serious problem is the judgmental tone of the document, which must have offended anyone who might legitimately have a different opinion. Indeed, I imagine that the tone of this document inflamed the passions of opponents and swayed people who might be neutral toward opposition. For example, the experts who worked on the EIS concluded that regional traffic congestion, noise, and air pollution would be reduced by the Driscoll Expressway, and that local problems would be controlled by engineering. Residents did not assume that noise barriers would be built, many did not want noise barriers, and many, perhaps most, simply did not want any latent intrusive sounds. They attacked the interpretations of the data on the quality of their lives, not the science per se.

Comprehensiveness

The document includes environmental, economic, and social considerations, emphasizing the importance of land-use and transportation planning. It looks at cumulative local effects and even regional effects, and asserts that all of these will benefit as a result of the Driscoll Expressway. What is missing is any sensibility towards personal and neighborhood effects, that is, how individuals living along the proposed route would react. Residents and many of their local elected officials did not accept the premise that the objective of the Expressway should be evaluated as an overall regional utility function; that is, it was not acceptable to increase noise, air contaminants, and other environmental consequences in their neighborhoods in order to improve traffic in other neighborhoods. They cared about the impact on them, their families, their friends, and their neighbors, not people who lived 5–15 miles away or people who traveled to the New Jersey shore during the summer months. This Driscoll Expressway EIS is an early example of the reductionist perspective that too often characterizes the position of agencies that badly want their project. With sufficient time, project opponents are able to craft arguments that expose the narrow viewpoint and broaden the issues that they argue should be considered.

Coordination

My efforts to explore this path were not very productive. People's memories have faded. By speaking informally to several officials, consulting media reports, and examining Governor Byrnes's memoirs, I found that the advocates of this project were quite certain of success, and did not take every opportunity to seek out individuals and groups that were likely opponents in order to reach a compromise. They did apparently, however, reach out to local planning staff in some of the municipalities. Indeed, they were, I think, misled into believing that support from technical staff meant support from local elected officials and the local public.

I cannot fault the Driscoll Expressway EIS for failing to understand the impacts of the short-lived oil shortage in 1973 and how it would impact the views of the new Governor Brendan Byrne. Governor Cahill, the previous governor, had approved the proposal, and the proponents assumed, perhaps naively, that his decision was final. The oil crisis clearly impacted Governor Brendan Byrne's decision (personal conversations and media coverage of his formal remarks, as noted above), but there was no oil shortage when this document was prepared.

I am less able to understand why so little consideration was given to the impact on open space, when the public has been extremely interested in preservation and has funded purchases of large tracts of open space with taxpayer and bond monies. The authors of the EIS indicated acreage that would be lost to the highway, and that there would be impacts on plants and animals, but did not give much credence to it. Thirty years later, the debate over Route 92 in New Jersey brought back the same issue with the same result, that is, the proposal was defeated on environmental grounds.

Accessibility to other stakeholders

Ultimately, the NEPA process exposed the details of the plan to scrutiny by the public and adamantly opposed environmental advocate groups, and to the skeptical eye of a new governor. The new governor understood the bigger picture of sprawl, the population of cities, energy dependence, and others. Overall, my review of the technical elements of the Driscoll Expressway EIS is that, like many projects of that era, it ignored lessons learned from the civil rights movement and later applied to the environmental justice movement, which is to say that satisfactory biological, chemical, and laboratory science, even with good engineering support, will not necessarily overcome broad ethical/moral, political, and social concerns.

Fate without an EIS

I cannot be certain. However, I believe that this project would have moved forward and ultimately been built without the EIS requirement and the presence of Governor Byrne. These two, in fact, worked in concert. Governor Byrne did not like the idea of this highway, as well as many other proposed highways. He was disposed to oppose it. The presentation of the EIS went badly for project proponents, which provided him with more than sufficient political ammunition to adamantly oppose the proposal. Had Governor William Cahill still been in office, I suspect that the highway would have been built. Governor Cahill had already agreed to support it, and the EIS, despite strong public outcry against the project along part of the route, and environmental group opposition, was remarkably supportive. Unfortunately, Governor Cahill passed away in 1996, so I have not been able to ask him any hindsight questions.

This EIS was a satisfactory planning document for a different era. The agency failed to adjust to the shifting political power realities that were taking place in New Jersey and in many other states. From a technical perspective, the document is satisfactory in almost all parts; but from a communication perspective, it is painful to read and must have infuriated many readers.

Hudson–Bergen Light Rail system

History of the proposal

On December 19, 1999, The Star-Ledger (the largest-circulation newspaper in New Jersey and sixteenth in the United States) released a public opinion poll of 804 residents that asked the public to reflect on the past twenty-five years of the twentieth century and identify the state's major failures and successes (Zukin 1999). By a margin of two to one, New Jersey residents identified the failure to stop suburban sprawl and to get commuters from automobiles to mass transit as the two major failures. In contrast, by a margin of more than five to one, the five major successes and achievements were: construction of the performing arts center in Newark, the Meadowlands sports complex, development of the Hudson waterfront, renewal of Hoboken, and efforts to clean up the New Jersey shore. Three of these five successes are directly tied to the Hudson–Bergen Light Rail system.

The Hudson–Bergen Light Rail system was a product of public, business, and government growing frustration with congestion and deterioration in older cities and suburbs. The signal political message was the founding of NJ Transit (NJT) in 1979. This progeny of the New Jersey Department of Transportation began by taking over and managing a variety of bus routes, some of which had been successful while others were floundering. In 1983, NJT began operating all of the commuter rail service in New Jersey, with a few exceptions. NJT is the largest public transit system in the nation and the third largest single provider of bus, rail, and light rail transit. The system's weekday daily ridership is now approaching a million. NJT has almost 2500 buses and 1100 commuter rail trains, including double-deckers (NJ Transit 2007). It operates a monorail to Newark Liberty International Airport, and in other ways is extremely active in providing multi-modal transit options.

In an announcement highlighting “record ridership,” NJ Transit (2007) underscored its light rail program. “Growth in rail was up 5.4% over the first quarter of FY07, . . . the Hudson–Bergen Light Rail ridership shot up 18.4% over the same period last year.” The Hudson–Bergen has had a long and complex political history, and environmental impact has played a major role.

In 1983, Governor Thomas Kean, who this author would characterize as a moderate Republican with a strong interest in cities, suburbs, and rural areas, reflecting on the issues of sprawl and distressed older cities, issued Executive Order 53, which created a Hudson River Waterfront Development Committee to assess ways of reducing traffic congestion, upgrading infrastructure, and redeveloping the waterfront. Governor Kean, along with Governor Byrne and the governors who followed, recognized the strategic location of the area.

The waterfront stretches approximately 18 miles from Fort Lee in Bergen County to Bayonne at the tip of Hudson County (see Figures 2.2 and 2.4); it includes a residential population of close to half a million in eight municipalities. Directly across from Manhattan West side (hence its nickname, the “Gold Coast”), this area was part of the industrial–port complex of the New York–New Jersey region. But, beginning in the 1950s and accelerating into the 1960s, a good deal of the industrial activity closed and railroads that ran along the Hudson River were underutilized or abandoned, which left thousands of abandoned contaminated brownfield properties.

Governor Kean's committee included senior state, county, and local officials, and regional representatives, as well as community representatives. In 1984, Governor Kean directed the New Jersey Department of Transportation to assess transportation options for the Hudson River waterfront. The Department reported that uncoordinated and unplanned decisions were being made that would hinder future redevelopment. Yet, not surprisingly, analysts stumbled over who should control the transportation rights-of-way and who should pay for the upgrades.

The committee also struggled with a decision about whether the Hudson River transportation projects should not start until there was an agreed-upon plan for all of northeast New Jersey. Governor Kean's administration prepared a plan to link the Hudson waterfront, the New Jersey Turnpike, and the New Jersey Meadowlands – the so-called “circle of mobility” concept. The plan, in essence, integrated a variety of already existing proposals for rail links, road extensions, bus ramps, a monorail or trolley, and a new tunnel to New York City. This multipronged effort detracted, temporarily at least, from the focus on the Hudson River waterfront, and brought some agencies and community groups into conflict with one another because they recognized that funds were limited. Debate over the circle of mobility proposal lasted for well over a decade, and other elements of it, in fact, have been built. But threatened with a loss of federal funds because of an inability to reach consensus, the state chose initially to concentrate on the Hudson–Bergen opportunities.

Some of the difficult negotiations were with Conrail, which owned the right-of-way. After lengthy negotiations, an agreement was reached with Conrail. The state purchased Conrail's right-of-way along the Hudson and provided it with an alternative route for its commercial traffic. In 1989, Governor Kean noted that he recognized the importance of the waterfront to the economic development of the area, but that transportation access was essential (Baehr 1989a). Yet part of the argument against the circle of mobility concept was caused by environmental sensitivity toward widening roads and building tunnels through sensitive wetlands areas. Many of those arguments have not been resolved.

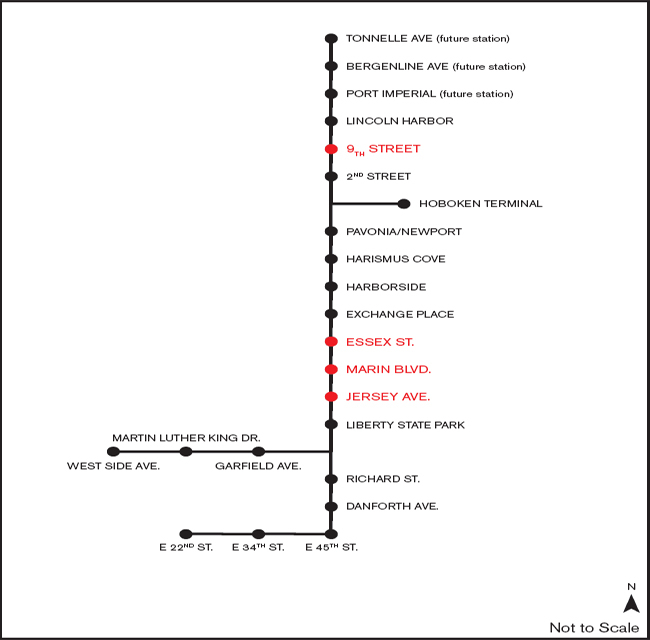

Light rail stations

Design concepts

In May 1989, the NJT Board agreed to spend $2 million on a federally required study to assess buses, trolleys, monorails, or automobile options. The draft EIS (NJ Transit 1992) was based on the idea of a thorough review before the investment of federal funds in large public works projects; that is, the analysis was expected to allow local officials, developers, and private citizens to participate (in Hudson and Bergen Counties).

Given the national and state competition for mass transit funding, the no-build alternative and low-cost options were real options, if the interest groups could not agree on a plan. Governor Kean and his advisers recognized that the state did not know with certainty what single option or combination of options would be most effective in garnering support. Indeed, it was not clear that any of the options could improve access for area residents and workers; engender economic development of the Hudson waterfront; preserve wetlands and protect the environment; and lead to a consensus for a transportation plan. The study focused on seven alternative plans for the corridor. These included a no-build scenario that maintained existing transit and roadway services; modest adjustments of transit and traffic (a band-aid approach); adding busways, park-and-ride lots, and a few trolley lines; constructing monorails; building new roadways; and a hybrid of all of the above.

NJ Transit organized a Hudson River Waterfront Advisory Committee to comment via an alternatives analysis/draft EIS (Baehr 1989b). The Advisory Committee was to help NJ Transit identify a “locally preferred alternative (LPA) for which federal and state funding would be sought.” After the study began, Martin Robins, project director (see below for interview), noted that he thought light rail might be advantageous, so it was added to the options (Baehr 1991).

This design was to rely on existing right-of-way from Conrail's River Line, and would run from downtown Jersey City west to a park-and-ride lot on Route 440 in Jersey City; next it would go north along the Hudson River waterfront through Hoboken and Weehawken, and under the Palisades through the Weehawken Tunnel to another park-and-ride lot to be located near the junction of Routes 3, 1&9, and 495 (see Figures 2.2 and 2.4 for regional and location diagrams). A little over a month later, Robins unveiled his staff's complete idea, which included a 15-mile light rail system, an express busway from the NJ Turnpike to the Lincoln Tunnel that crosses into New York City, and four large park-and-ride lots with 12,000 parking spaces. A major addition to previous plans was an extension of the light rail north to the Vince Lombardi rest area on the NJ Turnpike in Ridgefield Park. The justification was the opportunity to attract many thousand more additional riders.

Robins expected to finish the plan and hold public hearings by either March or April 1992. Following those hearings, local officials and the NJ Transit Board would agree to a locally preferred alternative and apply to the federal government for a grant to produce a final environmental impact statement (FEIS) and begin final design of the system. Robins hoped to obtain the grant for the FEIS by mid- to late 1992 and begin construction a few years later (Baehr 1991). The FTA approved NJ Transit's draft environmental impact statement (DEIS) in November 1992. The approval came two years after the study was first begun by NJ Transit. However, by that date, the NJ Transit Board had still not adopted the LPA. In February 1993, after 43 months of planning and negotiations, NJ Transit's Board of Directors adopted the LPA for the Hudson River waterfront.

Conflict and resolution

Interest groups offered dozens of suggestions. For example, a group of north Hudson County municipal officials and a coalition of community, environmental, and transportation advocates criticized the busway proposals as polluting and inefficient, and likely to conflict with light rail (Baehr 1990, 1993). In February 1993, when the NJ Transit Board adopted the LPA for the light rail, a set of four contentious issues remained, that I will summarize.

An extension to Bayonne had strong political support; the issue was cost. Yet the supplemental draft environmental impact statement (SDEIS) found the proposed extension to be much more cost-effective than initially expected, which temporarily solved the problem (see below for interview).

The Jersey City supplemental environmental impact statement (SEIS) highlighted a split in the city between two historical political districts, in which the SEIS became ammunition for both sides. The “City Center” option would have divided the historic Van Vorst neighborhood, whereas the proposed “City South” route would have affected the historic residential Paulus Hook community. Local commercial interests tended to favor the City Center route because it would serve their customers. Transit planners, developers, and many local officials supported the City South path because it would allow access to developable waterfront property. By offering detailed results, the EIS provided the basis of arguments for both positions.

In March 1995, NJ Transit Board member Amy Rosen, who chaired the agency's Engineering and Operations Committee, offered the following comment about the process: “Finding a way through 20 miles of the most densely populated county in the most densely populated state in the nation is not easy,” she said. “I am overwhelmed by the leadership of the public officials who had to deal with this” (Baehr 1995). In November 1995, NJ Transit published the SDEIS evaluations for the Bayonne extension and another for the Jersey City alignment. It is fair to say that the details and findings in these documents engendered considerable debate. However, because the EIS process that produced the facts was satisfactory to the parties, they focused their attention on information rather than arguing about a process to create facts. Fewer site-specific noises, dirt, construction-related, and other neighborhood impacts were found to be associated with the City South route, and this route was also less expensive and could be completed more rapidly. These factors were key elements in building a political consensus for the choice of City South.

The third unresolved issue was the construction of a station below Union City in the rail tunnel. This analysis was an environmental assessment because it was not expected to produce notable impacts (see Chapter 7 for an example). The station would be connected to the surface by large elevators. Cost was the key issue (see interview below).

In January 1996, the NJ Transit Board voted 5–0 to accept the supplemental EIS studies for Bayonne, Jersey City, and Union City, thereby amending the original LPA to include the Bayonne extension, Jersey City south alignment, and the Union City station. The amended plans were sent to the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) for review. In August 1996, the FTA published a “Record of Decision” in the Federal Register, and gave 30 days for public comment. Assuming no consequential disagreements, the FDA's record of decision meant that it had approved the final EIS.

The fourth unresolved issue was a route through Hoboken. The options were building in the densely developed eastern side of the city, or along a railroad spur on the western side of the city, which was far less developed, indeed clearly in need of redevelopment. What was interesting about this option was that elected officials and community representatives changed their mind as more information became available. Eventually, drawing upon neighborhood environmental activism, the western side of town was chosen (Jersey Journal 1997).

Environmental controversies regarding the Bayonne, Jersey City, Union City, and Hoboken project did not end with the EIS and record of decisions. In a densely developed area with centuries of industrial development, excavation and construction found historical settlement, uncovered rodents, and unwanted debris, and produced a considerable number of complaints about construction noise and dust (Torres 1997a,b, 1998a,b, 1999).

Nevertheless, the light rail system opened on April 22, 2000 from Bayonne (34th Street) and Jersey City (Exchange Place) with a spur. Then service was extended to Pavonia–Newport. In 2002, the light rail service continued to Hoboken Terminal, and 2003 it was extended to 22nd Street and Bayonne. It reached Lincoln Harbor In 2004, Port Imperial in 2005, and Union City and North Bergen in 2006 (see Figure 2.4). The current system has forty-eight electrically powered vehicles, each 90 feet long, air-conditioned, with a capacity of sixty-eight seated passengers and standing room for 120 more. Trains operate about every 10 minutes, with lower frequency during off-peak hours and weekends/holidays. Researchers have found that the light rail system has led directly to substantial expansion of residential and commercial development. In each case, the light rail system was linked to bus, ferry, and other rail systems. Daily ridership is about 40,000, which ranks this system below light rail systems in Boston, Los Angeles, Philadelphia, and seven others opened before 2000. Among those opened since 2000, only Houston has more riders.

The Hudson–Bergen line has not reached Bergen County, and original plans suggested this system would have 100,000 riders when completed in 2010 (see Wikipedia: “List of United States light rail systems by ridership,” http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_United_States_light_rail_systems_by_ridership). Some of this added demand was to come from real estate development, and that has been proceeding (although impacted by the economic slowdown). Other users were to come from finishing the line, which brings us to the last unresolved issue, the extension of the Hudson–Bergen Light Rail system into Bergen County, and how this should be done. The current length is less than 10 miles; if extended to Tenafly, it would be almost 21 miles.

Scoping Document for the Northern Branch Corridor DEIS

Nearly all the case studies in this book are final or draft EIS documents for large, complicated engineering projects. Here I have made a deliberate choice to examine a scoping document for an EIS. I summarize the twenty-two-page scoping document not because it speaks to environmental protection, but rather because it underscores that the EIS process has become a written exercise in diplomacy in many cases where the proposed project is in a densely developed area (US Department of Transportation 2007). Unlike the Driscoll Expressway EIS, which frankly dismisses public concerns as misplaced and even harmful to the environment and public, this scoping document reads like a diplomatic exercise. It begins by succinctly describing the project and its historical context. The second page is a legible map of the study area. Then the purpose of the scoping document is described. Notable are the last two sentences of the first paragraph:

The purpose of the scoping document is to provide information to the public and agencies regarding the Northern Branch DEIS process, issues, alternatives and methodologies. The broader purpose of the scoping process is to provide an opportunity for the public and agencies to comment on and provide input to the Northern branch DEIS as it is initiated.

(ibid., p. 3)

In contrast, as noted above, the Driscoll Expressway EIS pays virtually no attention to the public: the first sentence of the cover letter from the consultants sets the tone with respect to the public: “In May 1972 the citizens of New Jersey, by formal action of their elected representatives, instructed the New Jersey Turnpike Authority to proceed with the planning, design and construction of a limited access highway through Ocean, Monmouth and Middlesex Counties” (New Jersey Turnpike Authority 1972, page not numbered). The last line in the penultimate paragraph of the transmittal letter leaves very little space for public objections:

Based on this evaluation, we have not identified any significant damage that might occur to the environment as a result of the proposed Expressway. Further, appropriate safeguards and controls can be included in the design and implemented during construction so that the Governor Alfred E. Driscoll Expressway will actually enhance and improve many areas through which it traverses.

(New Jersey Turnpike Authority 1972, transmittal letter)

Rather than providing no alternatives, the options presented in the Northern Branch Corridor DEIS are labeled as “preliminary alternatives.” On page 6, the document uses the words “rethink,” “new perspective,” and “rethought” to discuss the process.

Readers of this book realize that assertions of “public” input need not correspond with decisions. But in this case, appearance seems to be equal to intention, which means that elected officials and agency representatives realize that this project has very little chance of success without a strong public mandate. The scoping document invites the public to consult the project website and post questions, register for testimony, and sign up for the website mailing list. Contact people are provided by name, with phone and fax numbers.

Six goals and objectives are stated. The first goal is to “meet the needs of travelers in the project area” (US Department of Transportation 2007, p. 13). The specific objectives for this goal are “attract riders to transit, improved travel time, improved convenience, provide more options for travelers, and improve services for low income/minority/transit dependent travelers.” This list of objectives is remarkably attuned to the complaints of the New Jersey public noted in the 1999 survey discussed above, and in following surveys, and is consistent with the concept of new urbanism and environmental justice.

The remaining five goals include advanced cost-effective transit solutions; encourage economic growth; improve regional access; reduce roadway congestion; and enhance the transit network. While the labels are not obviously directed precisely at securing public support, the tone of the language is clearly an attempt to be candid, an attitude that risk-communication studies show that the public appreciates. For example, the following is stated about advancing cost-effective transit solutions:

The Northern Branch project should allow for future transit expansion while at the same time provides a solution that is affordable to construct. With limited capital funds, the ability to advance projects in phases helps to keep the project affordable. Project scalability allows projects to be constructed without precluding future expansion projects. One of the criteria on which the Northern Branch project will be evaluated is the degree to which one phase of the project integrates into a more global planning effort for transportation improvement in the region.

(US Department of Transportation 2007, p. 14)

With regard to roadway congestion, there are several statements that neither promise the public a perfect solution, nor abandon them.

Major regional highways in the project area are heavily congested. There are a limited number of major highways, each serving intra-county and regional travel needs. Congestion in Bergen County is a growing problem, is likely to become more serious in the future. Transit strategies are unlikely to substantially reduce congestion, but can provide useful new travel alternatives for travelers trying to avoid congestion.

(ibid., p. 14)

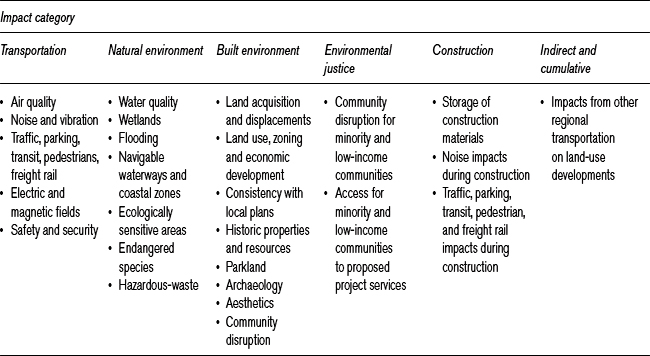

The project alternatives are not discussed until page 16 of this twenty-one-page document. They include a no-build alternative, diesel–multiple-vehicle alternatives, and electric light rail vehicle alternatives. While there had been considerable discussion of these alternatives, there is no evidence that the EIS had a predetermined outcome. Table 2.1 lists the general and more specific impacts, which look remarkably like those for almost every other urban transportation project I have seen.

Following the same theme, the reader will not be surprised by the content of the last two pages. They describe the “public involvement program.” Included are newsletters, a study website, a citizen's liaison committee, breakout sessions, agency coordination, small town meetings, and scoping meetings/public hearings. In fact, many of the communities have begun their own evaluations of this extension (Borough of Tenafly 2009).

Conversations with Martin Robins

Martin Robins was a colleague for many years, and I know of no-one who better understands the reality of creating, building, and managing a rail system in a complex political environment. His career has involved numerous challenging efforts. Martin Robins's career in transportation planning and policy extends more than three decades. He has the capacity to cut through details and get to the key issues.

An attorney, Robins was Director of the Alan M. Voorhees Transportation Center at Rutgers University, and now advises several Rutgers transportation research centers. Prior to that, he was project director of Access to the Region's Core, a three-agency partnership focused on the need for a new rail transit tunnel between midtown Manhattan and northern New Jersey. Robins had been director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey Planning and Development Department, as well as deputy executive director of NJT. Most important from the perspective of this EIS, he was director of NJT Waterfront Transportation Office, which planned the Hudson–Bergen Light Rail line.

Table 2.1 EIS elements in the Hudson–Bergen Light Rail study

Robins had no difficulty recalling the issues, facts, scientific debates, and politics of the Hudson–Bergen Light Rail project. I spoke to him about this project on various occasions, and we had a longer meeting on April 20, 2009. He agreed with my belief that local elected officials, their staff, and community groups pressed experts to make choices that were, in the long run, better for the environment and the public. When Robins began working on options for the Hudson–Bergen corridor, light rail was one possibility and bus lanes was another. The NJ Transit unit he headed met about a half dozen times with a citizens’ advisory committee. Public sentiment was for light rail and strongly against the noise, dirt, and smells of more cars and buses.

With regard to light rail routes, he has explained on several occasions that local officials strongly influenced the routes. For example, Bayonne's mayor and elected state representatives pressed for a location along the less densely inhabited eastern border of the long, narrow city of approximately 70,000 people. Robins's planning staff advocated a route through the populous, developed core of the city in order to generate more ridership and reduce automobile traffic. Local political pressure led to the selection of the eastern route, which, in the long run, he acknowledges turned out to be a better choice because the US military closed the vast Military Ocean Terminal facility in Bayonne. The location of the light rail has helped spur redevelopment of that spacious area for housing, commercial activities, and tourism. The location preferred by his staff would have provided less of a spark.

Robins and this author both enjoyed recounting a selection of the Jersey City route. Western and Eastern routes were proposed. It is not unkind to label the Western route as passing through an area that was a mess. The population was impoverished and redevelopment was hindered by massive hexavalent chromium contamination, a residual of deposition from PPG Industries, Occidental Petroleum, and Honeywell International Corporation. Honeywell has spent an estimated $400 million to remediate the area. Robins reiterated that he wanted to extend west from the route that was ultimately chosen, over Route 440, Roosevelt Stadium, and Society Hill in Jersey City. But the line was not extended because the course of the chromium clean-up had not been legally resolved.

The West Side alignment in Jersey City presented an interesting case of citizen preference affecting the profile of the route. The early design for the West Side alignment would have placed the light rail in an abandoned railroad cut 20 feet below the surface. The activist local population, mainly female, beset by poverty, underinvestment, and crime, argued that a sub-surface design would engender criminal activity; their arguments were accepted by the Robins team and the line's profile was lifted to street level at the site of their key neighborhood station.

The route in downtown Jersey City was strongly influenced by the development arm of Colgate-Palmolive and middle-class residents of the Van Vorst neighborhood. The light rail line now passes directly through property owned by Colgate, which strongly influenced city officials to locate the rail line on their property and avoided the hostile Van Vorst brownstone neighborhood. The Robins team had favored a different route, which served an old merchant street, passed by the edge of the Van Vorst neighborhood, and connected well with the Port Authority Trans-Hudson (PATH) Grove Street station, served by trains destined for both midtown and lower Manhattan. Nevertheless, the routing selected through the Colgate property and other vacant land has attracted a prodigious amount of residential and office development.

The alignment in Hoboken was controversial, with the Robins Team favoring an easterly alignment along the waterfront, serving newly emerging developments. Citizen groups favored a westerly alignment along a railroad right-of-way that was surrounded by junk yards and the Palisades cliffs. The resulting westerly alignment, the choice of which was influenced by environ-mentalists and political considerations, has attracted far more economic development than had been anticipated. Hoboken has been the city in this area with the strongest environmental protection advocates. The environmental community opposed the easterly light rail alignment because it would cut somewhat into a historic rock formation (Castle Rock) and would have occupied the occasional recreational resource of Frank Sinatra Drive. They wanted light rail, opposed any more bus lanes, and called for a western route through Hoboken. The choice they argued for, in fact, has worked well, as this formerly dormant west side of Hoboken has sprung to life and the area has been developing rapidly.

The construction of the West New York (New Jersey) station was a challenge for technically oriented planners. State legislator Robert Menendez (now US Senator from New Jersey) wanted a station in the Palisades tunnel under Union City and West New York. This meant drilling vertically 150 feet from the densely populated street atop the Palisades through hard rock to a station in the tunnel. The cost was high, and the experts initially were concerned about the station elevators’ capacity to process users quickly enough. Once pressed by Menendez, the engineers found that the station was feasible, and this Bergenline Avenue station has been one of the most successful in the entire line. Large numbers of people use it for work, and the local population uses the station on weekends to visit otherwise inaccessible shopping areas along the light rail line. The estimated actual use has more than doubled initial ridership estimates.

Robins, an attorney, planner, and transportation expert, sees the EIS process in this case as a regional planning mechanism. Without it, the project very likely would have failed. The EIS required gathering and evaluating a diverse set of data, and those data were used to craft a design that fits local needs.

An excellent communicator and writer, Robins worked hard to make the document readable, specifically to deliver a clear story in the executive summary and throughout the text. He recalled spending hours editing and re-editing until the message was clear.

Reacting to my question about “cumulative effects,” Robins indicated that his team spent a great deal of time considering these, especially when the community would propose a change in the design. While they emphasized each segment of the line, the entire project had to offer a clear net benefit in terms of reducing air pollution and noise from cars, increasing ridership, and economic development in the region as a whole.

By now, the reader may conclude that this evaluation seems a little too good to be true; that the author, supported by Martin Robins, must surely have exaggerated the political and public input that influenced this light rail system. Hence we also discussed the generalizability of the Hudson part of the Hudson–Bergen line to other locations. Hudson County has had a history of powerful political leaders that cannot be ignored by federal agencies. This history means that citizen groups and elected officials can make a persuasive case, and federal and state officials would be foolish to ignore them. The step-by-step planning process required by the EIS fitted the political environment of this area like a glove. The Bergen part of the project has not moved ahead, and Bergen County elected officials are perhaps less powerfully placed and less reliant on their political leadership than their Hudson counterparts. Is this the reason why that part of the project has not been completed? I doubt if it is the major one – but it is a reason.

A second important point is that, compared with many other projects with which the author is familiar, water and air pollution and solid waste management were not such powerful factors in this case as they often are. Social and economic impacts were consistently important, whereas traditional environmental factors were of greatest importance only in Jersey City and Hoboken.

Evaluation of the five questions

Information

There have been more than two dozen EIS documents, primarily because of the proposed extensions of the light rail system. I have not read every page of every one of these documents. Some of the information, such as concern about chromium contamination, is provided in substantial detail, supported by a good deal of scientific information. Other information is treated more lightly. My sense is that the agency focused much of its attention on the issues that concerned local elected officials and community groups. In other words, the scoping process helped define the focus of the environmental assessments. Clearly, the staff attempted to explain the information without unduly steering it, although it is hard not to be directive in some of these cases.

Comprehensiveness

The document includes a broad spectrum of environmental, economic, and social considerations, perhaps more than I have ever seen in a single project. The emphasis is on land use and transportation planning. The documents consider cumulative effects, especially on land use and economic redevelopment. If there is any shortcoming, it is perhaps that environmental issues were less developed than were economic and social ones, which concurs with Martin Robins's statements. However, that reality may relate directly to the on-the-ground reality of the area. A great deal has been expected of the approximately $2 billion investment in mass transit. Proponents created some ambitious goals (over 100,000 daily commuters, 33 million square feet of commercial development, 58,000 new jobs, 40,000 new housing units, and cleaner air). It is too early to measure the full impacts. However, initial evidence suggests that, notwithstanding the international economic slide, the Hudson–Bergen project has been successful. For example, Goldman Sachs has built a forty-two-story tower on the former Colgate-Palmolive site, and thousands of new rental sites and some for-sale housing has been constructed within half a mile of the Jersey City rail stations. A major hospital in Jersey City relocated to be along the line. Surveys show that residents living within half a mile of the stations are far less dependent on automobiles than their counterparts elsewhere (Wells and Robins 2006).

Coordination

There was a major effort to provide information, formally and informally, to other federal, state, and local agencies. I have never seen an EIS process that had more meetings, documents, and opportunities for access to the process, albeit elected officials’ access was the most important.

Accessibility to other stakeholders

Looking back at the building of the Hudson–Bergen Light Rail system, I would not deny the usual political influence in the process. Key elected officials, such as Governors Byrne, Kean, Florio, and Whitman, local members of the US Congress such as Congressmen Roe and Menendez, as well as the Commissioners of the New Jersey Department of Transportation, had the power – which they used – to influence this set of projects. They could and did exercise vetoes and strongly influence options. If you ride the Hudson–Bergen line, you will find some unusual changes of direction that would not have emerged without political influence. Yet, looking back at decades of scoping, draft, final, and supplementary EISs regarding the Hudson–Bergen Light Rail system, the author concludes that the EIS process helped New Jersey officials form a consensus that otherwise might not have materialized in a densely developed and highly politicized environment. The EIS process constituted the evidence to undermine many of the projects that were part of the initial highway elements of the redevelopment plan for the Gold Coast. The process also allowed technical experts to prepare the environmental impact estimates, which were critiqued by proponents of one or another option. The EISs served as fodder for the political process. The EIS process forced local interest groups to bring their concerns to the table in a timely and controlled fashion. It allowed decision-makers to stand back and watch the survival of the politically fittest ideas emerge. I think that less credible scientific information would have been used were it not for the EIS process; and, despite the charge that the EIS has been abused by interest groups to obstruct projects, in this case it is hard to believe that these projects would have been built with relatively strong public and political support without the EIS process.

Fate without an EIS

I believe this project would have not have moved forward without the EIS requirement. The process forced to the table people who otherwise might have sabotaged the project behind the scenes. It was molded to fit local needs, and it illustrates the idea of a federal government planning process (see Chapter 8).