| 7 | Animas-La Plata, Four Corners: water rights and the Ute legacy |

Introduction

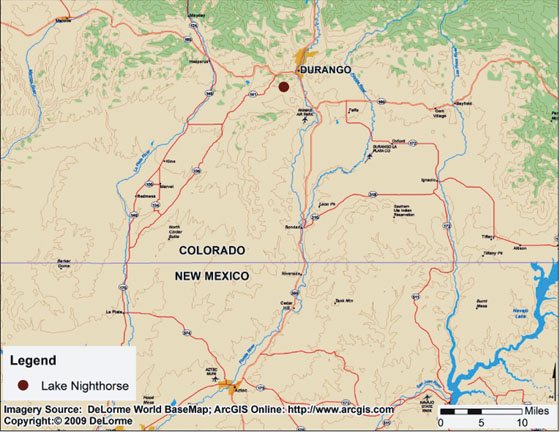

In 1868, after wars and skirmishes with the rapidly spreading Anglo-American population, the Ute Indian tribes moved to southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, the so-called Four Corners area, where Utah, Colorado, Arizona, and New Mexico meet (Figure 7.1). The Utes expected the new reservation to provide sufficient land and water. Their lands, however, were reduced and water was anything but plentiful. One hundred and fifty years after relocating to the Four Corners area, the Utes will receive a water supply from the Animas and La Plata rivers, the two major surface water sources, which settled their water claims.

This chapter has two objectives. The first is to illustrate an environmental assessment (EA) and Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) declaration, which were briefly described in Chapter 1. The reader will recall that an EA is a preliminary analysis. After completion of an EA, the federal agency must decide whether a full-blown EIS is required or whether it can declare a FONSI and move ahead with the project.

The second goal of the chapter is to describe one of the longest-standing political, moral, environmental, and social debates about a single project that has ever occurred in the United States; the debate involves multiple Congresses, Presidents of the United States and federal courts. The Animas-La Plata (ALP) project has had multiple EISs, supplementary EISs, and supplements to supplemental EISs. This chapter will attempt to tell the story of what has to be one of the most interesting applications of the NEPA process in US history.

General Animas-La Plata project area showing location of Ridges Basin dam and reservoir

Context

The history of the ALP water project begins with its geography. The Four Corners region is the only place in the United States where four states meet. Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah share a common border demarcated by a brass plaque (Figure 7.1). The region is remarkably beautiful, with wooded mountain peaks reaching 10,000 feet and valleys of 4000 feet; and multiple national parks, such the Grand Canyon National Park (about 180 miles west of Four Corners in Arizona), Arches National Park (170 miles north in Utah), Bryce's Canyon Park (about 330 miles west in Utah), and Mesa Verde Park (63 miles east of Four Corners). In places, mineral deposits have been found, including gold.

While scenery and minerals are positive attributes, water on this high Colorado Plateau has been a major constraint. Average annual precipitation in the region is 12–15 inches, which means that the region is semi-arid. There is insufficient water for all the uses desired by residents, and water has proven to be an ongoing challenge.

After the 1848 US–Mexican war, the Four Corners area became part of the United States, and in 1868, after many skirmishes from Montana to the Mexican border, the Navajo and Ute tribes were relocated to reservations in the Four Corners area. As the value of the land became more obvious to Anglo settlers, the Indian tribes’ territories were reduced and their limited water supply further constrained. With the main stems of the Colorado River to the west and the Arkansas River to the east, the two major surface water supplies in the area are the La Plata and Animas that flow through La Plata County in Colorado and San Juan County in New Mexico (Figure 7.1). In a region where there are four state governments, the Federal Bureau of Reclamation as a major landholder, county and local governments, and the Ute and Navajo nations, it is not surprising that the water rights have been a flash point for over a century.

In 2009, the population of the seven counties in the Four Corners area was 340,000, an increase of 6% since the year 2000 (US Bureau of the Census undated). The 35,000-square-mile area is sparsely populated with a gross population density of fewer than ten people per square mile, which is about the same as the states of North and South Dakota. A good part of the area has no population, and there are only two clusters: one in Farmington, New Mexico with a population of about 45,000; the second in Durango, Colorado with a population of about 14,000. Almost 120,000 of the people, about one-third of the total, self-identified as American Indian in the US Census.

The populations: Utes, Americans, and environmentalists

The Utes

The Utes were the first recorded population in the area we now call Colorado and Utah. They first met Anglos in the late sixteenth century, when they established relationships with the Spanish (Simmons 2000; Decker 2004; Rockwell 2006). After the 1848 war with Mexico, more Anglo-Americans moved west and decades of strife ensued, especially with the arrival of the Mormons. The tension grew rapidly after gold was discovered in the Pikes Peak area.

On March 2, 1868, the Utes signed a treaty that moved them to the Western Colorado territory. Notably, Abraham Lincoln had first asked the Mormons if they wanted some of the land; Brigham Young declined (McCool 1994). A series of treaty revisions took back most of the land the Utes received. Conflict, treaty revisions, and givebacks were the common pattern.

The Utes have had a difficult time trusting US leaders, with good reason. The Anglo-Americans wanted to convert these nomads to farmers, and at the same time were competing with them for resources, notably water. The Utes have a broader view of the significance of water than their Anglo counterparts, which persists in the twenty-first century. Dinar et al. (1995) report on a survey of Utes and Mormons, which asked about more than a dozen dimensions associated with water. Values exceeding 100 imply agreement between the Utes and the Mormons; values between 90 and 100 represent no relationship; and values less than 90 imply divergent views. With regard to practical uses of water, the number was 146, indicating strong agreement. But with regard to spiritual or religious significance attached to water, the number was only 10, and it was only 30 for the questions about the meaning of water.

In 1988, the Colorado Ute Indian Water Rights Settlement Act was signed by President Reagan. The act required that the ALP project water be provided to the tribes by January 1, 2000. If the water was not available, the Utes have the right to renegotiate. The Utes learned the hard way that good lawyers were essential to getting a fair shake of the resources. An article in the High Country News, which focused on ongoing litigation with the state of Utah over land and water, offers insight about Ute feelings:

Elderly Ute woman: “you're like a rattlesnake on a hot rock. You've got the forked tongue.”

Luke Duncan, member of tribal council: “We feel like we just can't trust white people. The jurisdiction case is far from over; it's going to affect everything we do for a long time.”

Jonas Grant, tribal director of natural resources: “The people feel a lack of trust about the state; they keep trying to control what we have.”

While tribal council member Ron Wopsock added that there “will never be trust between the Indians and whites,” a local Anglo was quoted as follows: “my biggest concern is being able to work together with the Indians. If we can't we're wasting our time.”

(McCool 1994, pp. 2–4)

The Anglo-Americans

In 2006, when she was interviewed for an oral history, Stella Montoya lived on a cattle ranch in La Plata County, Colorado (Montoya 2006). Her family had raised sheep and cattle in Colorado and New Mexico longer than she could remember. Her father had been a sheep rancher, as was her husband for much of his life. She was one of five children and was the mother of six children. Yet only one of her children was a rancher, which she saw as an indication of the increasingly precarious position of ranching in this area with so little water.

At the time of this interview, she was chair of the water conservancy organization in the region, and her husband, who had passed away, had been chair for 30 years. Stella Montoya represents an extraordinarily well informed perspective on the importance of water in the region and relationships with the Utes and environmentalists, although her views are very personal.

Shortly after the interview began, she offered her first remarks about water:

Where my dad's farm was, we had plenty of water. But when we moved into La Plata, at first it wasn't so bad, but as time went on it got drier. They've . . . been working on that [La Plata] project for years, [the] early 1900s when they started working on that project. One time my husband came home and he was so happy because they were going to have it pumped through the mountains and come down. But then they took that project away from us. And every time, . . . they kept changing it. Every time they'd decide on something, then they'd move it because for some reason they couldn't have it there you know, the environmentalists kept moving it down, and so that's where it is now.

(ibid., p. 4).

She described how her husband went to Washington, DC, and each time he returned they expected the project to get the final go-ahead, only to be disappointed. Studies would continue, but a final decision was not forthcoming. She noted that perhaps all they were doing was providing job security for Bureau of Reclamation employees: “I kept telling him [her husband], I said, that's just job security, that's all” (ibid., p. 6).

She emphasized that the major hydrological problem is that when it rains, and when the snow melts, the water rushes down the mountains and is gone before it can be used. The dam is needed to capture and manage the flow. Rather than quitting the political endeavor to capture and store the water, she noted that they would get some water for irrigation because some of the water held back by the dam would leak into the ground and that water would be captured by the ranchers.

A key section describes her views of the Utes:

If it hadn't been for the Utes, I can tell you, we wouldn't have a project. Environmentalists tried their very best to separate the two of us, to make us enemies. (p. 8). The Utes said: We're partners and we're going to stay partners. (p. 9) We've worked as a team, Colorado people and our people and the Indians (p. 20).

Ms Montoya's opinions of the environmentalists reflected considerable frustration and anger.

Well some of the things they brought up, they were ridiculous (p. 16). They don't care about us. In fact, I think the squaw fish have more benefits. They talk about the endangered species, and we always figured out that we're the endangered species (p. 17).

Stella Montoya voices the all-too-familiar viewpoint that environmentalists are outsiders who try to impose their values on local people:

And see most of those people, they're not involved with ranching. And some, they would come from all over . . . would come to testify on these hearings and I don't think that's right. I think a person should be where they are because they know the locality and they know more about the country than somebody from Washington or California or anywhere else (p. 22). You know, people from back east, they don't understand our problems. Why would you want to build, spend so much money to build the dam to hold water? No it doesn't make sense to them (p. 24).

Among her final statement there was reference to the signing of agreements to build five projects on September 30, 1968. Her husband was at the ceremony, and while he got his picture taken with President Lyndon Johnson, she notes that their project (ALP) was the only one not built. “We're still waiting, hoping, working” (p. 25).

The “environmentalists”

I admit to disliking the term “environmentalist” because it assumes values not always held. In the ALP case, the environmentalists were powerful opponents of the dam and lake, and they were remarkably effective in changing this project. Every impact element in Table 7.1 (see p. 184) was questioned over many years, and in multiple EISs and EAs. In essence, the environmental groups could not prevent the dam from being constructed. However, their arguments fundamentally changed the project. I cannot possibly do justice to the sophistication and breadth of their assertions. Hence I will focus on only one of their arguments.

Robert Wiygul, attorney for the Sierra Club, on behalf of the Earth Justice Legal Defense Fund, Sierra Club, Four Corners Action Coalition, and Taxpayers for the Animas River, submitted a set of arguments on about project economics (letter to Pat Schumacher, Bureau of Reclamation. April 17, 2000, www.angelfire.com/al/alpcentral/mycommentss.html). He began by asserting that the EIS failed to provide a benefit–cost analysis. Noting that the 1980 EIS contained a benefit–cost analysis, the Bureau, he asserted, had gone on record as acknowledging the relevance of such analysis to this project. In 1995, the Bureau updated the analysis. Having twice included benefit–cost analyses, he concluded that, in concurrence with NEPA requirements, a new update of the benefit–cost analysis should have been in this document. It was inappropriate to not update the benefit–cost analysis simply because the project is now being built to settle Indian water rights and claims.

Wiygul advanced the argument that NEPA requires consideration of factors beyond environmental quality, especially if those factors are relevant to decisions. This EIS, he argued, should have spelled out who will pay for the project, because the project had become more expensive. Next, he noted that the discount rate (interest rate charged for borrowing) had changed since the agreement was signed, and the higher cost meant that the benefits were only about half compared with what had been anticipated in the initial analysis.

An updated benefit–cost analysis, he concluded, would show that the project should not be built. Environmental groups offered alternative nonstructural options, such as redistributing water rights to the Utes and relying on diversion from other storage facilities in the region.

Wiygul continued by criticizing that the EIS did not specify what the water was going to be used for. Quoting directly from the purpose of the project in the supplemental EIS (SEIS; see immediately below), he asserted that the EIS was not legally acceptable because, without a specified use for the water, there was no possibility of developing competing alternative actions to compare with the preferred option. (This is grounds for rejecting an EIS for not meeting the NEPA no-action alternative requirement.)

Attorney Wiygul concluded that the only logical use for the water was that the tribes will market it. He argued that the tribes will not be able to easily market water because they will encounter jurisdictional issues with state governments and they will be responsible for operation and maintenance costs, which would be a serious problem for them. He concluded: “no private sector investor – whether for-profit or not-for-profit – would direct resources into such a fanciful scheme, regardless of beneficiaries” (letter, op. cit., p. 3).

The economic arguments continued for many more pages. This sample is sufficient to demonstrate the sophistication and flavor of the environmental groups’ arguments against a project that many of them believed was an environmentally degrading economic boondoggle.

The Animas-La Plata saga

The purpose of the ALP project was summarized in the Final Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (FSEIS):

Implement the Settlement act by providing the Ute Tribes an assured long-term water supply and water acquisition fund in order to satisfy the Tribe's senior water rights claims as quantified in the Settlement Act, and to provide for identified M&I [municipal and industrial] water needs in the Project area.

(Federal Register, January 4, 1999, section 1.3, p. 1.9)

The project certainly did not begin with those objectives. The official authorization was in 1968 as part of the Colorado River Basin Project Act (P.L. 90-537). The initial idea was for 191,200 acre-feet of water to be stored and used for irrigation, municipal, and industrial water uses in Colorado and New Mexico.

The law was passed prior to NEPA. The first sets of EISs were written in the 1970s and the FEIS published in 1980. However, President Carter ordered that no new water projects be started.

The abrupt stoppage likely would have ended this project without the Utes. In 1988, they reached a settlement with the federal government. The Colorado Ute Indian Water Rights Settlement Act (PL 100-585 as amended in 2000, PL 106-554) was passed, and it redirected the water project from primarily providing irrigation water for Anglo-Americans to the Utes and local users. However, additional changes were required when the Colorado pikeminnow, an endangered species, was found in the area.

In 1999, the Bureau of Reclamation examined not only structural alternatives, most notably the dam, but also so-called nonstructural options such as reservoir storage in different places, a cash outlay to buy water and bring it to the region – a total of ten alternative projects. Ultimately, the structural option prevailed. An agreement was reached in the year 2000 to scale it back to 120,000 acre-feet and to limit the flow out of the reservoir to 57,100 acre-feet (Draper 2006). Overall, 62% of the water is allocated to the tribes and 38% to nontribal bodies (Rodenbaugh 2009).

While the so-called ALP-Lite project moved ahead at a slow pace, the cost escalated to an estimated $500 million, prompting a year 2003 meeting by the Bureau of Reclamation to discuss the escalation of costs from $337.9 million to $500 million. The approved ALP plan included a pumping plant on the Animas River, and a 2.1-mile-long, 76-inch pipeline between the pumping station and a 276-feet high dam and reservoir (Lake Nighthorse, see Figure 7.2), which was named after retired US Senator Ben Nighthorse Campbell, a long-time advocate. The project also includes an outlet tunnel used to release water when required, and a pipeline for the Navajo nation from Farmington, New Mexico to Shiprock (about 22 miles, see Figure 7.1).

The construction of the pumping plant began in April 2003 and was completed in April 2004. In July 2006, the Denver Post (Draper 2006) reported that the project was 40% complete. Preliminary work for the dam construction also began in 2003, and a great deal of the work on the dam was completed in 2004. On October 17, 2008, The Durango Herald reported that the ALP project was 97% completed (Rodenbaugh 2008). The lake eventually was to cover about 1500 surface acres. The pumping station went online during the spring of 2009 (US Bureau of Reclamation 2009). Also in 2009, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (2009) noted that a fish hatchery located in western Colorado was going to introduce 100,000 rainbow trout into the Animas River at Durango in late June 2009. This was partly to address any losses from the dam project and from a disease that was affecting these fish.

Lake Nighthorse

In June 2009, $12.1 million of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act was appropriated to ALP to be used to build a Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED)-certified building for the project and for part of the pipeline from Farmington to the Navajo Nation (US Bureau of Reclamation 2009). The US Department of the Interior (2010) annual report for the year 2009 discusses the project, requesting $27.4 million to build a pipeline from Farmington, New Mexico to Shiprock for municipal and industrial uses.

In June 2010, Robert Waldman, the Bureau's environmental specialist for the project, indicated that the reservoir was 63% filled (phone conversation with the author, June 30, 2010). The schedule for complete filling would be determined by snow melts and rainfall, and the area had been receiving below-normal rainfall. Nevertheless, he expected the reservoir to be filled by the end of 2011.

The 2002 Final Environmental Assessment

On July 14, 2000, the US Bureau of Reclamation (2000a,b), in cooperation with the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Colorado Ute Indian Tribes, released an FSEIS for the ALP Project. This FSEIS added to those of 1980, 1992, and 1996 (US Bureau of Reclamation (1980, 1992, 1996). Secretary of the Department of Interior Bruce Babbitt executed a Record of Decision on September 25, 2000 (US Bureau of Reclamation 2000b), which adopted an ALP project that would involve construction and operation of the system described above.

The year-2002 FEA (US Bureau of Reclamation 2002) in many ways was an afterthought, or perhaps better labeled a residual action required by the larger project. By the time it was written, the tough, multi-decade-long political decisions had been made. Nevertheless, three pipeline relocations had to be completed before the dam could be built and operated. Like other EAs, this one follows the form of an EIS, but with less detail. For example, the FEA has two technical appendices. However the main text is only fifty-seven pages. The EISs in this book were over 250 pages long and some were much longer. In order to present the flavor of the document, I have followed its sequence, which I have not necessarily done in the other chapters of this book.

The stated purpose is to relocate three pipelines so that the Ridges Basin Dam and Reservoir could be constructed. The report also includes a brief discussion of the modifications of a natural gas distribution pipeline, a county road, and electric transmission lines. However, these were not described in detail because the plans were not completed.

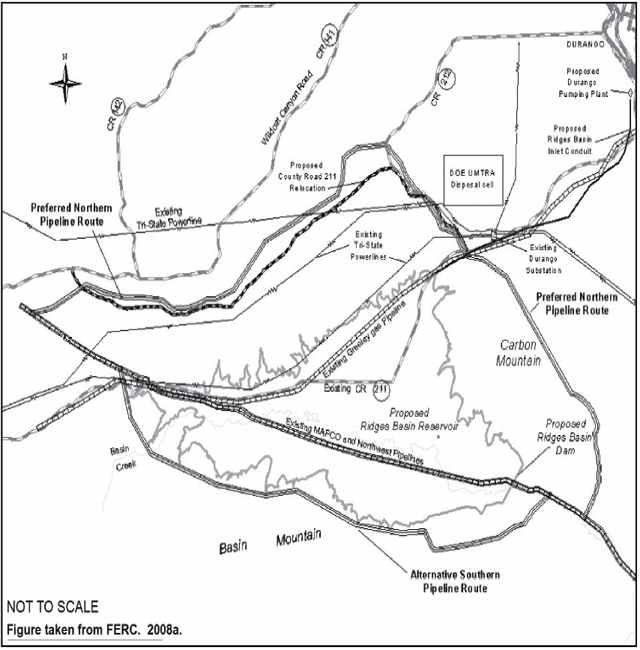

The three pipelines were as follows (see Figure 7.3):

- a 26-inch-diameter natural gas pipeline, owned by Northwest Pipeline Corporation

- a 16-inch-diameter natural gas liquids pipeline, owned by Mid-American Pipeline Corporation (MAPCO)

- a 10-inch-diameter natural gas pipeline, owned by MAPCO.

Proposed Northwest Pipeline relocation in relation to other Ridges Basin features

The project background section summarizes the entire ALP project, but quickly jumps to the pipeline relocations. What this means is that the reader who is interested in the history would need to do additional searching to learn more about the context for the pipeline relocations (US Bureau of Reclamation 1980, 1992, 1996, 2000a,b). Only one person complained in a letter about this inconvenience, and the Bureau argued back that it was not necessary to reproduce all the comments that already were published and available to interested parties.

Page 3 of the FEA identifies the need to relocate the pipelines, and mentions thirteen government agencies that had been contacted, including the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC), the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS), the Bureau of Indian Affairs and each Indian nation, and state and local governments. A full-blown EIS would have provided more details about the roles of each of these federal, tribal, state, and county agencies.

FERC is important as a cooperating agency because it is responsible for determining if natural gas facilities are in the public interest. FERC must issue a “Certificate of Public Convenience and Necessity” before a pipeline can be relocated (see Chapter 5). Northwest Pipeline Corporation, the pipeline owner, is responsible for obtaining the certificate from FERC. The FWS was pivotal because of concern about endangered species, especially golden eagle nests and elk calving areas, as well as other species described above, which led to a biological assessment. Consulting with the Bureau of Indian Affairs and individual Indian tribes was essential to avoid conflicts over disturbing culturally significant historical grounds (Winter et al. 1986). This reader infers that the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms issued a permit to use explosives, that the US Army Corps of Engineers issued stream-crossing permits, and that the US Department of Energy was consulted about the proximity of part of the pipeline to the DOE's uranium mill tailings waste storage cell near Durango, Colorado (the author has visited that site). However, an EA rarely goes into the same detail about organizational relationships as an EIS.

Alternative actions

A no-action alternative is always required. In this case, however, the no-action alternative was not acceptable to the Bureau because the dam could not be built. Figure 7.3 shows that there are two basic options: one goes around the north side of the reservoir and the second around the south side. The Bureau examined seventeen alternative north and south options, finally settling on the two that are discussed in this FEA. Northwest and MAPCO proposed to build somewhere between 12.9 and 20.7 miles of new pipeline. They would abandon some of the old pipeline, and would not enlarge the pipeline capacity. MAPCO was considering changing its 10-inch line from gas to oil, which engendered considerable concern about a potential oil leak, leading to an oil risk report attached to the FEA. Except for a 0.6-mile segment, the design was to build all three pipelines in the adjacent 75-foot rights-of-way.

The report notes that, in addition to the 150-foot pipeline right-of-way, approximately 40–85 feet more would be required during construction. And small additional spaces would be needed for a metering station and other ancillary facilities. After contaminants were removed, some of the abandoned pipeline would be removed, and other parts excavated and left in place. Figure 7.3 shows the two major options.

The northern route is 6.9 miles long, in La Plata County, Colorado. The document points out that much of it is outside the Ridges Basin drainage area, and about half is owned by the Bureau of Reclamation, with the remainder owned by La Plata County. Much of the terrain is characterized as “low ridges with minimal visibility” (US Bureau of Reclamation 2002, p. 2-7). Unlike many other EISs and EAs, this one provides a feel for the terrain. For example:

The last mile or so of the alignment at its west end skirts along the edge of an alluvial valley of Wildcat Creek before it crosses several ridges to reach the west tie-in point . . . In general, grades in or near valley bottoms and on ridge tops are relatively flat . . . One cross slope of about 26° occurs to the north of the HDD exit point, where potentially deep and/or unstable colluviums may exist.

(ibid., p. 2-8)

The southern route is 4.3 miles long and most of it is located within the Ridges Basin. The description foretells the decision against the shorter southern route: “The west end of the Basin Mountain is an identified landslide area” (ibid., p. 2-9).

Regarding access to build the pipeline, the FEA describes the northern route as follows: “access to the proposed construction area is generally very good along most of the northern route alternative” (p. 2-10). In contrast, access to the southern route “is limited, with only two access points located along the alignment” (p. 2-12). Then the report once again identifies the southern route as steep, requiring “unconventional construction practices leading to a massive construction scar” (p. 2-12). The word “landslide” was used to describe the southern route in multiple places. The FEA continues that part of the southern route would require up to 275 feet of right-of-way in order to stabilize the construction in this difficult terrain.

The tabular data show that the northern route actually requires more land than its southern counterpart. However, this is because the northern route is longer. Before even describing the environmental impacts, the site descriptions clearly are making a case to reject the southern route.

The environmental impact section of the report examines a set of potential impacts, in essence concluding that the overwhelming majority are not significant and/or are temporary. Table 7.1 lists the impacts that were considered.

The disadvantages of the southern route continued to be emphasized. For example, “landslides are of concern for pipeline construction, primarily along the southern route” (ibid., p. 3-2). The document points out that the northern route lies within 750 feet of the DOE Durango Uranium Mine Tailings Remedial Action (UMTRA) disposal cells for uranium mill tailing. However, the text adds that field inspections showed that the pipeline would not affect the “integrity of the UMTRA disposal cells site” (p. 3-3).

The very next paragraph once again sends a clear message about where this decision is heading. “Several geologically hazardous conditions were identified during review of the southern route, including landslides, construction on steep slopes, and rockfall hazards” (p. 3-3).

Table 7.1 Environmental impacts considered for Animas-La Plata, Four Corners

Physical environment |

Air quality |

Biological resources |

Aquatic resources |

Social and economic environment |

Cultural resources |

The discussion of water resources examines potential impacts on local groundwater as a result of converting the 10-inch natural gas pipeline to oil. For a project that was only proposed, a great deal of attention was devoted to this hypothetical. Frankly, the author was surprised to find a fourteen-page presentation about a petroleum products spill for a hypothetical project. I surmise that the Bureau of Reclamation would have been criticized for not addressing this possibility. But the Bureau, I believe, could have asserted that it would assess the risk and impact of a spill upon receiving a final proposal for a conversion of the gas line to oil. I was unable to determine why they chose to add this report to the document. However, after reading the document, I concluded that the Bureau was under pressure to avoid anything that could stop a project that had achieved enormous political support after decades of political and legal debate. Hence I speculate that the Bureau chose to be proactive about a hypothetical risk, rather than ignore it, which is not what the vast majority of EAs I have read have chosen to do; that is, they do not assess hypothetical impacts of hypothetical projects.

The oil spill analysis discusses why pipelines are used, the potential toxicity of a spill, and what the Bureau would do to minimize the risk. The document notes that pipelines are the safest way of transporting oil, much safer than tankers, ships, trucks, and railroads. That is, deaths, injuries, and spills are much more frequent with other transportation modes, which may also be much more expensive. Yet the report acknowledges that pipelines can fail and that the result can be injuries, ecological damage, and water pollution.

The oil spill analysis summarized US Department of Transportation data about the frequency and impact of oil spills. It describes various kinds of petroleum products, including crude oil, blended stocks, diesel fuel, fuel oil and gasoline, jet fuel, kerosene, toluene, xylene, benzene, and others. Benzene, which is about 2% of gasoline, is the fraction of greatest concern because of its toxicity at low concentrations, and the report uses rainbow trout as a sentinel at-risk organism.

The authors describe the worst-case scenario for the northern and southern alternatives:

The worst possible case scenario for petroleum leak or spill in Ridges River Basin Reservoir would be during winter when low air temperatures slow evaporation of petroleum product components, such as benzene . . . Under this scenario, toxicity levels of benzene during a large spill (1677 gallons) would be the same as with the full volume of 120,000 acre-feet [0.002 mg/l in the first hour] . . . the lower volume of Ridges Basin Reservoir would still provide sufficient dilution to eliminate toxic affects of benzene.

(ibid., p. A-1)

The report then goes on to note that evaporation would occur, but that some heavy hydrocarbons would persist in the new reservoir and get into the food chain. The key observation is that only a small portion of the northern route drains into the reservoir, whereas almost all of the southern route drains into the reservoir:

Although the northern route has a slightly greater risk associated with a pipeline leak, because of the greater length of pipeline, the risk of reaching Ridges Basin Reservoir is not as great as the southern route because of the more gentle terrain associated with the northern route . . . Because the southern route is located on steep slopes, the likelihood of a leak reaching Ridges Basin Reservoir is considered to be greater because of the steep gradient toward the reservoir. We expect [a leak] to move quickly, both below ground and above, if a leak occurred from a pipeline on the southern route.

(ibid., p. A-2)

If the oil pipeline change was made, the report notes that the Bureau would install block valves at either end of the pipeline to control the flow. The key conclusion, consistent with the FEA message, is that the northern route is preferred. The report then describes other steps to be taken to prevent a spill, and to reduce it should one occur.

The message about the northern versus southern route continues with wildlife. The FEA focuses on the golden eagle, elk and mule deer, again emphasizing the advantages of the northern route. Golden eagle nests are identified as sufficiently far away from the proposed northern route to not be a problem. The major concern is noise caused by blasting and visibility. The authors expect attenuation of noise impact by steep ridges. They noted that the closest wintering eagles were found along the river, 1–2 miles east of the northern route. The Bureau pledges to avoid construction within a quarter mile of an eagle's nest from December–June in the three areas along the northern route where they were identified.

With respect to elk, the report is clear about the preference for the northern route:

Construction and operation along the southern route would significantly impact both elk calving areas at the base of Basin Mountain and elk migration over Basin Mountain. Impacts to elk calving areas from construction and operation along the northern route are not considered to be significant.

(ibid., p. 3-11)

In remote areas, endangered and threatened species are always a consideration. The Bureau of Reclamation prepared a biological assessment, which was attached. Their conclusion, arrived at jointly with the FWS, was that each of the federally listed species was unlikely to be adversely impacted. The biological assessment examines the potential impact on Colorado pikeminnow, razorback sucker, bald eagle, and southwestern willow flycatcher, as well as two federal candidate species. The two fish species of concern could potentially be impacted. Accordingly, two minor adjustments were made in the construction plan. One was not to use local water to test the pipeline; the second was to routinely monitor the pipeline with on-site inspections and remotely by technology. The bigger decision had already been made, which was to limit the average annual withdrawal to not more than 57,100 acre-feet of water and also to operate the reservoir to meet the needs of the endangered species (see above).

Unlike the oil spill analysis, the twenty-page biological assessment was not surprising, because there is nothing hypothetical about these potential impacts. The key point made in the biological assessment is that consultations were held between the Bureau of Reclamation and the FWS. Notably, this section ends with six bullet points that are aimed specifically at reducing the risk of a spill from the pipeline, and responding should a spill occur. In short, while the bulk of the appendix provides considerable detail about endangered species in the region, mostly in tabular form, the message is that the Bureau of Reclamation has a plan to reduce any risk. This appendix, along with the oil spill appendix, demonstrates that the Bureau is proactive and not afraid to deal with sensitive environmental issues.

Cultural resources of this area had already been surveyed extensively during the EIS processes for that dam. The pipeline relocation project studied a 500-foot-wide corridor along the pipeline route. The FEA commits to following an agreed-upon research protocol planned in consultation with the tribal nations, avoiding sites and recovering artifacts as required.

The visual impact again clearly distinguishes between the northern and southern routes. Construction of the northern route, the report notes, could result in “significant” visual impact during construction. The impact, however, is characterized as temporary, that is, for 3–5 years before revegetating occurs. Furthermore, the report stipulates that a landscaping plan will be developed that tries to minimize the visual impact. Several of these actions are identified. For example, “a directional drilling construction technique would be used to bore through Carbon Mountain, thereby reducing the potential for visual scarring to occur on Carbon Mountain as a result of the new pipeline alignment” (ibid., p. 3-21) The analogous description for the southern route is less charitable: “Construction of the southern route alternative would result in temporary and permanent significant visual impact” (p. 3-21).

Other potential impact areas listed in Table 7.1 are summarized in a sentence or two as not significant or not new impacts; in other words, they had been in one of the earlier EISs. This includes even socioeconomic impacts. Clearly, some construction employment would be required, but it is not discussed as it is in many other EISs and EAs.

In addition to the three pipelines, the FEA briefly touched on three other projects because the Bureau of Reclamation interpreted them as having a common geography and timing, that is, related to the larger dam project. These are relocation of a county road, an electrical transmission line, and an 8-inch gas pipeline. The descriptions are brief, and the Bureau of Reclamation notes that it will use NEPA processes to undertake additional studies as required to conclude that the cumulative impact of these projects, and the three pipelines that are the focus of the FEA, have not changed from what already has been considered in the larger ALP project.

Environmental justice and Indian trust assets are addressed in two sentences, which in essence indicate that the Bureau of Reclamation has an agreement with the tribes that it will adhere to.

By the time the reader arrives at the fifth section, which is called “Recommended Action and Lists of Commitment”, the recommendation is obvious. The northern route is preferred because of its access and less dangerous geological conditions, as well as the potentially important ecology, visual impact and potential erosion associated with the southern route. The cultural impact along the northern route is described as avoidable or capable of being mitigated by following the agreement signed with the tribal nations.

FONSI declaration

The eight-page FONSI closely resemble dozens that I have read. I use it to illustrate the form of the declaration, as well as the substance of this specific case. It begins with a one-page letter from Carol DeAngelis, the area manager for the Bureau of Reclamation's Upper Colorado region to “interested agencies, Indian tribes, organizations and individuals” (FEA cover letter before FONSI). The letter mentions the three pipelines that were to be relocated and, the preferred northern alternative, and concludes that the “northern alternative will not result in any significant impact on the environment other than those previously identified in the Final Environmental Impact Statement . . .” (FEA cover letter before FONSI). A phone number is provided for anyone with questions about the environmental assessment or the entire project.

The FONSI declaration itself introduces the project as a whole and the need to relocate three pipelines, once again mentioning the choice of the northern route. It mentions the history of the project, beginning with 1980 and the Colorado Ute Settlement Act Amendments. The background also includes two paragraphs about the need to relocate the pipelines, and the Bureau of Reclamation's role as the lead, and then mentions the cooperating federal agencies such as FERC.

The next one and a half pages summarize the alternatives. The no-action alternative is presented in two sentences as a choice that would stop the entire project. After mentioning the consideration of seventeen alternatives, the declaration summarizes the southern and northern routes. The reasons for choosing the northern route are presented, including a potential oil spill from the hypothetical oil pipeline, easier access to the site, and space for temporary work along the northern route, as well as much more severe slopes and geological hazards along the southern route. The FONSI also expresses concern about possible impacts on calving grounds, erosion, and visual impacts along the southern route. The declaration notes potentially greater cultural impacts along the northern route, but asserts that they will be avoided or mitigated.

The next three pages present a snapshot of environmental impacts, including air quality, geology, soils, water resources, noise, vegetation, wildlife, endangered and threatened species, cultural resources, land use, transportation, visual resources, and recreation. The presentation consists of simple declarative statements with citations back to the FEA and a variety of EISs. Most of the statements are three or four sentences. The longest is about visual resources, and I quote it here as an illustration of the kind of messages being transmitted, I believe, to persuade readers to go along with the FONSI declaration:

The FSEIS outlined several measures to be implemented by Reclamation to help reduce impacts associated with the construction and presence of the physical component of the ALP Project. The FEA analysis indicated that no new effects that previously identified with the FSEIS would occur. As indicated on page 3-283 and page 5-20 of the FSEIS, Reclamation would employ the services of a qualified landscape architect to develop and supervise implementation of a landscaping plan that specifically focuses on minimizing the visual impact of the pipeline relocation project. Measures specific to the pipeline construction include:

- Areas graded and entrenched along the right-of-way would be restored to original grades.

- A directional drilling construction technique would be used to bore through Carbon Mountain.

- Contour slopes following backfilling pipeline trench to blend with existing terrain.

- A visual mitigation plan would be developed for the corridor and would include measures to reduce the long-term visual impact of the right-ofway (requirement for the FERC approval process).

(FEA FONSI, p. 6)

The final two pages of the declaration describe coordination, beginning with a statement about the distribution of the draft FEA to 197 government and nongovernment parties – in essence, anyone who is interested. The fact that eleven comments were received is noted, as is their origin. The declaration points out that several commentators have called for a full-blown EIS, but the FONSI concluded that “it was determined within the FEA that since no new significant environmental impacts are associated with the abandonment and relocation activities, that the FEA would fully meet all the NEPA to compliance requirement for this action” (FEA, FONSI, p. 7).

The final section of the declaration describes consultation with twenty-six Native American tribes and the FWS. The conclusion is that no new concerns were identified. Hence the recommendation follows that “Reclamation, within the FEA, selected the Northern Route as the preferred alternative for relocation of the three gas pipelines. This Finding of No Significant Impact [underlined in FONSI] has determined that implementation of the preferred alternative will not have any significant effect to the human environment and that relocation construction activities should proceed” (FEA FONSI, p. 8).

This FONSI, like others I have read, is terse and reassuring. It is an effort to simply demonstrate that decision is justified by the facts and that the process followed regulations.

Public reactions

By the time this FEA was written, the project was well under way and the vitriolic public and political debates were over. Nevertheless, following regulations, the Bureau of Reclamation held public hearings. A scoping meeting was held in Durango, Colorado in November 2001. Seven people commented on the pipeline relocation project. The public comment period was closed in January 2002, and the Bureau received fourteen letters, e-mails, and notes, which, according to the Bureau, were considered before the draft EA was prepared. The draft EA was released in April 2002: eleven comments were received from the public and from federal agencies.

Several members of the public testified or submitted notes. One, for example, thanked the Bureau for a chance to review the project and stated that she was in “full support of the northern route”(FEA, Appendix C, comment 1). A second was troubled by what he stated was plagiarism of parts of the oil spill analysis from another EIS. This writer added that the EIS was in the public domain, and hence the quotation was not illegal. However, not to cite the authors “borders upon unethical” (FEA, Appendix C, comment 6). The Bureau responded that this oversight would be corrected.

One writer was concerned about impacts on golden eagles, and urged the Bureau to work with the FWS to protect endangered species. The Bureau agreed. This writer was also concerned about the potential impact of an oil spill from the rebuilt MAPCO pipeline. The Bureau responded that if MAPCO does follow through, then further analysis will be undertaken.

FERC provided several comments. One was a concern that the analysis of the relocation of County Road 211, the Greeley Gas company facility, and the Tri State electrical transmission facilities were not presented in sufficient detail in the document. The Bureau's answer was that none of these facilities had sufficiently detailed plans to warrant action at that time.

A local county representative pointed out that they were considering options for realigning Route 211 and would notify the Bureau of Reclamation when final decisions were made. A staff member of the FWS indicated he had spoken with a Bureau staff member and had nothing else to add. A regional manager of the DOE offered three comments that required minor revisions of the text. A representative of the State of Colorado indicated that the issues they had previously raised had been addressed, with two exceptions, which were relatively minor.

The remaining comments were more interesting. Representing a not-for-profit organization, Steve Cone and Vena Forbes Wilson argued that a full-blown EIS was necessary to address a possible pipeline rupture, and that the cumulative effects presented in the study had not been sufficiently addressed. The Bureau responded that the oil spill analysis presented in the FEA would be updated if MAPCO decided to move forward with converting their gas line to oil, as would the cumulative effects analysis. In June 2002, MAPCO sold the line in question to another company, and there has been no proposal to convert the line to oil (Waldman, phone conversation, 2010, op. cit.).

Douglas Grew, a local resident who lives near and drives by the northern half, opposed the choice of the northern route. He feared bisecting the animal migration path. The agency responded that this had been extensively studied and that it believed the impact would be limited, even during active construction. Grew added that more cultural resources would be disturbed by the pipeline on the northern route than on the southern side. The Bureau disagreed, asserting that the sites would be avoided if at all possible, and if they could not be avoided, then the cultural artifacts would be removed. Grew asserted that more recreational sites and forest land would be disturbed, and more would have to be spent, than on the southern option, and that access would be difficult on the northern slope route. The Bureau commented that access was even more difficult on the southern side and that overall the greater potential impacts were clearly on the southern route.

Grew continued that the scar created during construction was intolerable to many, and that it was “clear that those of us who both live along Wildcat Canyon Road and drive on it on a daily basis do not count much in this analysis” (FEA, Appendix C, comment 4). The Bureau's response was that visual impact would be reduced by locating the pipeline in less visible and less prominent areas, and that a scar on the south side would be even more visible.

Representing the Cedar Hill Clean Water Coalition, Jacob Hottell argued that all bald eagles might be harmed by the proposed relocation, and that the project would reduce the flow of the Animas River. The Bureau did not agree with the second point, and responded that the biological assessment in this FEA report, along with the FWS, agreed that bald eagles would not be threatened.

Perhaps the most interesting comment was from an attorney representing the Pueblo of Laguna. The letter did not object to the proposed action. Rather, it was a statement of the Pueblo's understanding of their agreement with the Bureau of Reclamation about the project. The Bureau did not contest any of the assertions. As noted earlier, the tribal nations had learned the need to be represented by attorneys in their dealings with the Anglos.

Interview

Dr Frank Popper is Professor of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University, and also teaches at Princeton. Frank is well known for originating the acronym LULU to describe locally unwanted land uses, such as landfills, incinerators, and factories. In 1987, Frank and his wife Deborah wrote a short paper, “The Great Plains: from dust to dust” (Popper and Popper 1987), which asserted that the semi-arid Great Plains of the United States, Canada, and Mexico were losing population and jobs, and that it made sense for the region to become a “Buffalo Commons” of perennial grasslands where the buffalo and other native species could roam. The Poppers received considerable hate mail from the region accusing them of being easterners with little knowledge or stake in their words. Yet the Poppers’ ideas have become increasingly accepted and embraced in the Great Plains.

I asked Frank Popper some questions about the ALP project because I felt that he could place ALP in the context of changes that have been occurring in the west. I interviewed him on June 30, 2010. He noted that Animas-LaPlata is:

actually a hangover from a generation ago. In 1986 the Bureau of Reclamation decided that it would no longer be a dam-building agency, but instead a water-conservation one. In practice this meant that it would start no new projects, and it hasn't. But it would try to complete ones existing in 1986, like ALP. As a result the Bureau is often blamed for practices it no longer endorses, as HUD [Housing and Urban Development] is blamed for high-rise low-income housing, which it has been legally prohibited from building since 1968. Animas-La Plata, whatever its fate, will be the last such large project in western Colorado.

Dr Popper noted that the Buffalo Commons idea was partly a reaction to these massive building projects, such as the 1944 Pick–Sloan Plan that created six large artificial lakes just east of and in the Great Plains by damming the Missouri River. The lakes, known as the Great Lakes of the Missouri, represented a compromise between the Bureau of Reclamation and the US Army Corps of Engineers.

He noted that Buffalo Commons, in contrast to these mega-scale projects, is a land-use vision for a sustainable environmental end-state. Frank Popper: “It is Plan B taking over from a Plan A that has been failing for over a century.” He continued that the ALP project would not recur today for good reasons. Agriculture there is not competitive with agriculture elsewhere in the country and Canada, especially after the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA). Raising cattle is the last choice, not a particularly good one. AnimasLa Plata is an economic boondoggle that may or may not help local Indians. He noted that other similar projects are often not used as anticipated. Many dam projects, for instance, end up being used by weekend boat enthusiasts rather than for their ostensible agricultural purposes.

Popper sided with environmentalists in most cases because projects hurt ecosystems, and/or were economically inefficient. He admits frustration when politics trumps good EIS and other science-based analyses. He suspects that the BP Gulf of Mexico oil spill will change people's minds about large-scale projects in difficult environments. At a minimum, the disaster will lead to better analyses in EISs and risk analysis that decision-makers will take into account. He points to difficulties of dealing with methane in places like Wyoming, where natural gas and oil exploitation are taking place, as another current example of large-scale projects with poorly understood impacts. He said “too many games have been played with [environmental impact and cost–benefit] analyses over the years” by decision-makers who use these tools to get the decisions they want, rather than to understand their decisions’ implications.

Evaluation of the five questions

Information

There is a limited amount of information in this FEA, and it is pretty clear how it was to be used to support the northern route. There is no plausible no-action alternative, and the southern route is portrayed as a bad choice because of the risk of landslides, impacts on elk calving grounds, a visible permanent scar, and a potential oil spill from a non-existent oil line into the Nighthorse reservoir. The limitations of the northern route are not avoided. But they are characterized as avoidable or capable of being mitigated, buttressed by some thinking about mitigation and resilience options. The pro-north route message is blatant and helped by writing that is above average for an EA and EIS. I could be mistaken; however, this EA feels slanted toward the northern route. Some language is devoted to mitigating problems that would be encountered; but not much.

My routine complaint is the lack of economic analysis. I do not understand why we are not told how many workers would be employed to build the pipeline, unless none of them were being hired locally, or the numbers are trivial compared with the numbers brought in to build the dam, reservoir, pumping station, and long pipelines to carry the water. Of course, had this information been included, I would not have needed to speculate.

Comprehensiveness

The EA lists and briefly summarizes the impacts, with a few exceptions. The main focus is on landslides, access to the sites, visual impact, and others just noted. In other chapters, I have critiqued the economic analyses for being superficial. Here, there are none. Surely the longer northern route would, I assume, create more construction jobs and more injuries to construction workers. Perhaps I am wrong. But without the data, I was forced to guess.

Coordination

The Bureau of Reclamation tried very hard to coordinate with the FWS because of the endangered species issues, and in general it methodically listed its outreach efforts with cooperating agencies. With the exceptions of FWS and FERC, these were not emphasized in the FEA. However, as noted earlier, I speculated that the oil spill and biological opinion were the product of the agencies trying to avoid any charges of insensitivity to environmental and cultural issues.

Accessibility to other stakeholders

Powerful local and national stakeholders played key roles in this project. The EA does not do justice to the struggle between the Anglo-Americans, Indian Americans, and environmentalists, who had fundamental differences about the value and meaning of this project. For the Anglo-Americans, it started out as a chance to continue ranching as a well as to add more urban development. For the Utes and Navajos, it was an opportunity to get back part of what they thought had been promised to them in 1868. For the environmentalists, it was a chance to take an ethical position against large-scale projects with high cost–benefit ratios that also radically alter ecosystems. Each had multiple opportunities to argue in this EIS venue, before Congress, and in the courts. And for the Bureau of Reclamation, it was a project that they were carrying for all three groups, but especially the tribal nations. This project, more so than any other in this book, had the elements of a soap opera played out in multiple venues among parties with a lot at stake.

Technically, the accessibility of this EA could have been improved by using mapping technologies that would have allowed a simulated flight over the north and south routes to show the locations of landslide-prone areas, areas that would have been scarred by laying the pipeline, and many of the most visually oriented impacts discussed in this EA.

Fate without an EIS

The EISs and EAs testify to a markedly changed project over two decades. The 1980 and 2000 EISs are different. Did the EIS contribute to this change, or were they the places to record the changes? I think more of the latter than the former. In the end, regional and national politics won out over science. However, having the EIS requirement and later other major pieces of action forcing environmental legislation made it possible for the Utes and environ-mentalists to press home their views and arguments. The tribal nations and the environmental groups smartly used NEPA and other tools to challenge the original idea, which primarily was water for Anglo-Americans.

Even the EA in this chapter, I speculate, was so carefully composed because the Bureau knew the opponents of the dam were looking for a legally actionable gap in the document to challenge the project. The well-conceived arguments by Wiygul demonstrate that in the year 2000, the environmentalists were still trying to defeat the dam, and in 2002, the tribes, in their comments about the EA, were trying to make sure that what they had agreed to was the Bureau's policy. Furthermore, a more practical reality was that the pipelines were buried beneath the dam location. They had to be removed because, as Waldman (phone conversation, 2010, op. cit.) noted, the Bureau's experience with removing pipelines underneath dams after the fact shows that risk and cost would be substantially increased. This was a project that was too far along to stop. It would have been larger and more destructive without the EIS process.