CASE STUDY 6

Death of the Dividend?

Adrian Wood

AIMS, OBJECTIVES AND THEORETICAL SETTING

Our aim was to investigate whether or not European companies are changing the way they return cash to their shareholders. Traditionally, European firms have distributed cash via the payment of a stream of dividends. We wanted to see if that was changing and, specifically, if dividends were losing ground in favour of share repurchase programmes.

The survey didn't aim to investigate when companies distribute cash to shareholders – which should only happen if they have truly excess capital and no positive net-present-value (NPV) projects to invest in. We were only interested in the distribution technique, i.e., dividends versus share buy-backs.

Of course, classic corporate finance theory maintains that, when a company does decide to return cash to shareholders, how it does so is irrelevant (under assumptions of efficient capital markets and the absence of transaction costs). Investors are no better or worse off if the company pays a dividend or carries out a share buyback. For evidence of this, consider the following:

A company has 100 m shares, each worth E1, giving a market capitalisation of E100 m. The company also has E10 m of excess cash to give back to shareholders. The company can either pay a dividend or carry out a share buy-back:

a) If it pays the E10 m of cash as a dividend – equal to a dividend of E0.1 per share – then after the distribution has taken place, the market capitalisation of the firm drops to E90 m. The company still has 100 m shares outstanding, but each share is now only worth E0.9. Investors are left holding E0.1 of cash and a share worth E0.9, giving a total of E1. (Investors are no better or worse off after the cash distribution has taken place.)

b) If a firm instead chooses to buy back shares, then it pays no cash dividend. Instead, it uses the E10 m to repurchase 10 m shares and cancels them, causing its market capitalisation to drop to E90 m. There are now only 90 m shares, each still worth E1. (Investors are no better or worse off after the cash distribution has taken place.)

We hoped our survey would show whether or not such theory tells the whole picture behind corporate dividend and distribution policy.

METHODOLOGY

The study period for the survey ran from 1993 to 2000. We chose this period for one reason in particular: in 1993, share buy-back programmes were unfeasible in many European countries thanks to onerous tax regulations and corporate laws that banned them outright. However, by 2000, almost all countries in Europe had changed their taxes and their laws so that share repurchases were possible. For example, in Finland, it wasn't until September 1997 that share repurchases became legal. We thus hoped to capture how such changes would impact on corporate dividend and distribution policy.

In all, our survey included 127 companies taken from among Europe's 500 largest firms (by market capitalisation). By choosing such large companies, we aimed to avoid young, fast growing companies (with plenty of positive NPV projects) which tend to pay out less cash to their shareholders than mature companies do.

We also wanted a broad geographic spread in order to be sure to include companies from different tax regimes and with diverse investor bases. In the end we included companies from ten countries, with the biggest constituents being the UK (23%), Germany (21%), and France (20%). The smallest exposure was Austria, with just three companies included.

Additional considerations for inclusion in the sample were that the company must have kept the same dates for its financial year over the course of the study period, it must have published earnings figures dating back to 1992 and it must have been floated since then too.

Thomson Financial provided much of the data for the survey. However, share buy-back data was gathered directly from corporate investor relations departments.

RESULTS: DIMINISHING DIVIDEND SIGNALLING POWER

Traditionally, one of the main functions of dividends has been their “signaling power”, whereby investors can gauge the health of a company by its ability to continue to pay out a constant stream of cash. As such, in the past, companies have been reluctant to cut their dividend, even if they wanted to reinvest the profits within the business, for fear that the stockmarkets will read the dividend cut as a sign of weakness.

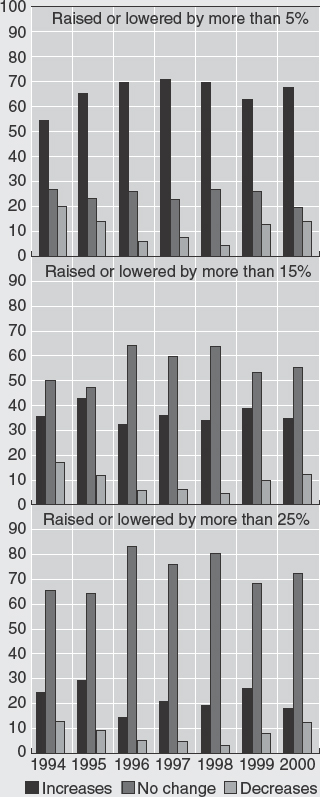

Our research confirms that such behaviour is still very much in evidence today. Figure C6.1 shows how very few companies ever cut their dividend, and when they do it is usually a drastic cut.

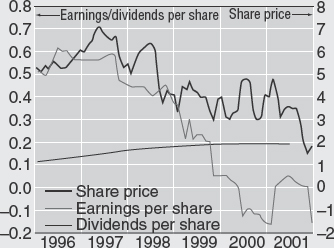

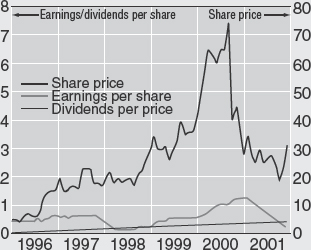

Nonetheless, while companies appear to cling religiously to the belief that they must maintain a steady dividend, investors, on the other hand, seem to be focusing less on dividends – perhaps because standards of financial disclosure and corporate governance have improved so much in recent years. Instead, shareholders appear to take much more notice of a company's earnings than its dividends. Indeed, earnings often appear to lag share price as investors respond to earnings announcements even before a company's actual figures are quantified or broadcast to the market. Consider the case of British Airways, as shown in Figure C6.2, where the company's share price clearly tracks its earnings, and not its dividends.

Figure C6.1 All or nothing? The percentage of European firms that raised, lowered or maintained dividends each year, 1994–2000

Source: CFO Europe and Thomson Financial

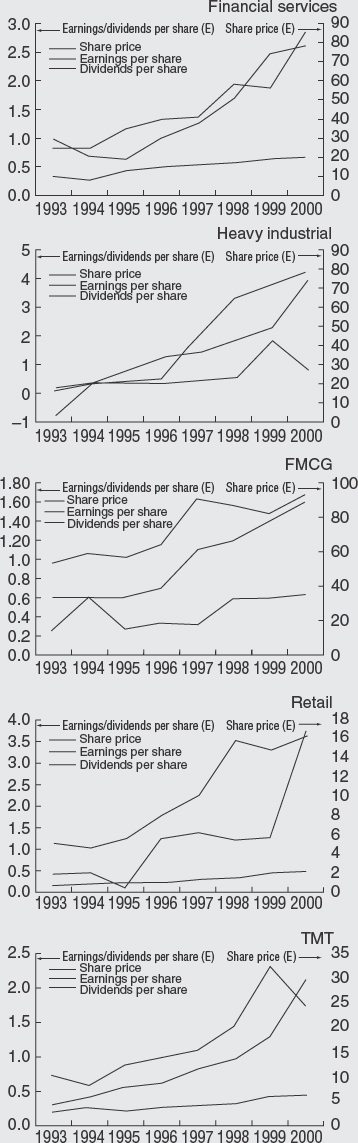

It all suggests that dividends may slowly be losing their significance as a barometer of future corporate performance. And British Airways is by no means alone. If you plot similar graphs for the five biggest sectors in our survey, then similar patterns emerge, as Figure C6.3 shows.

Figure C6.2 Crash Landing. At British Airways, share price has tracked earnings, not dividends.

Source: corporateinformation.com

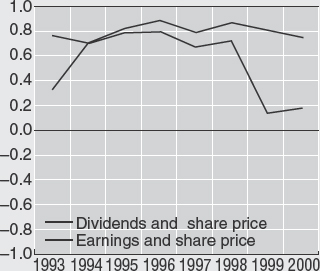

And the trend is further repeated when analysed for the entire 127 companies in our survey. As Figure C6.4 indicates, in 1993, the correlation between changes in share price and changes in dividends was extremely strong, supporting the notion that dividends did indeed possess signaling power. By 2000, however, stock prices were more highly correlated to reported earnings than to dividends.

It appears earnings become particularly significant in determining share prices when earnings fall significantly. Under these conditions some corporations attempt to create the illusion of “business as usual” by sustaining last period's nominal dividend per share. This established dividend obligation can potentially amount to a figure larger than the current earnings per share. Under these circumstances investors are no longer fooled and punish the share price accordingly, suggesting dividends no longer offer such a smokescreen to corporate performance.

RESULTS: GREATER RELIANCE ON BUYBACK SCHEMES

Despite the fact that most companies in Europe stick steadfastly to paying dividends, our survey shows that they are also starting to use share buybacks too. In fact, buybacks are growing in importance at the expense of traditional dividends.

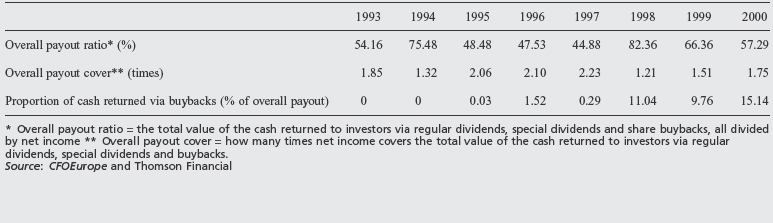

As Table C6.1 shows, while the percentage of net earnings returned to shareholders each year has barely changed between 1993 and 2000 – at around 55% – the amount of cash returned via buybacks has grown significantly. In 1993, no cash was returned through stock repurchases, while in 2000, 15% of all cash returned to investors came via buybacks.

Why are share buybacks becoming a more important part of distribution policy in corporate Europe? There are several possible explanations:

Figure C6.3 Earnings rule. Dividends are losing their significance as a barometer of corporate performance.

Source: CFO Europe and Thomson Financial

Figure C6.4 Is “dividend signalling” dead? The correlation between earnings and share price, and between dividends and share price.*

* Correlation: a score of +1 means the variables are perfectly positively correlated. A score of –1 implies that the variables move in opposite directions.

Source: CFO Europe and Thomson Financial

a) Flexibility for companies: When a company starts paying a regular dividend, it becomes like a contract and it's hard to persuade investors to let a company reduce it. Buybacks are more flexible and give a company more scope to decide when is the best time to return cash to shareholders. With share buybacks, a highly cash-generative company can return cash to investors whenever it is excess, but decide to retain it whenever it identifies good investment opportunities.

b) Flexibility for investors: Whereas dividends force all shareholders to participate in a cash distribution – and so also force them to incur tax – buybacks let investors choose when to take part. Those who want cash now, or to take a tax hit today, can sell some of their shares to create “home-made” dividends. Those who don't can hang on to their stock.

c) Tax: Dividends give investors an income, whereas share repurchases give them capital gains. In many countries, capital gains tax is lower than income tax, which makes repurchases more efficient than dividends as a way of returning cash. In Germany, for example, investors who hold a share for longer than one year are exempt from capital gains tax, whereas all dividend payments incur income tax. If the majority of a company's investors incur lower capital gains tax than income tax then it makes sense for a company to reduce its dividend and return more cash via buybacks.

d) Transaction costs: In addition to the increased managerial and investor flexibility, buy backs can also lead to a reduction in transaction costs – both for the company and its shareholders. As a repurchase equates to little more than a “buy” order for a broker, many of the costs of a dividend payment are not incurred. And investors aren't forced to incur the costs of handling their dividend payments.

e) Signalling Power: For those CFOs who still believe traditional dividends can serve a valuable signaling role, why shouldn't buybacks carry an equally potent message? This idea is intuitive as an announcement of a buy back scheme inevitably increases latent demand and signals management's confidence in the future performance of the stock or that the stock is currently selling at or near the lower end of its trading range.

Table C6.1 Buyback bonanza. While there are no clear trends in the proportion of earnings returned to investors, buybacks have increased in significance as a means of distribution

The results of CFO Europe's survey suggest that CFOs are increasingly taking these factors into consideration. Not that any companies in the survey have abandoned their dividend entirely in favour of buybacks. That could be for historical reasons – it's difficult to get rid of a dividend that investors have come to rely on. It could also be that the tax preferences of investors are very varied, with some preferring income, and others preferring capital gains, leading CFOs to set a distribution policy that is made up of both income (dividends) and capital gains (share buybacks).

RESULTS: THE CASE OF INTEL

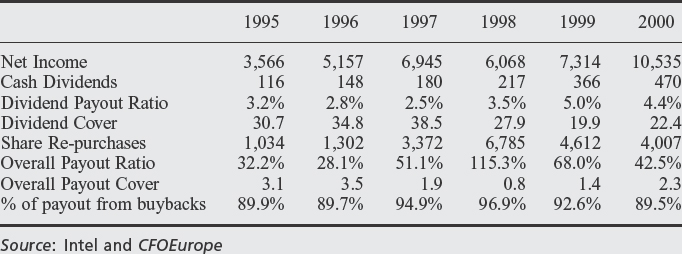

Intel, the $33.7 billion (E38.4 billion) US-based computer chip manufacturer, is an example of a large corporation that has moved a long way towards distributing cash via buybacks rather than dividends. Between the start of 1994 and the end of 2000, Intel paid out $1.6 billion in dividends. But over the same period, it returned almost 14 times as much cash ($21.8 billion) by repurchasing its shares and cancelling them, as Table C6.2 shows.

Intel has adopted a policy of continually paying only a token dividend, possibly because the US Inland Revenue Service wouldn't stand for a company disguising its dividend entirely as buybacks in an attempt to enable investors to circumvent income tax.

This low annual dividend aids both managers and investors. Managers, by paying such a low dividend, are furnished with flexibility to adjust the overall payout ratio in light of current earnings and future growth potential without wild swings in share price. This is demonstrated by the fact that Intel's payout ratios have oscillated wildly – between 28% and 115% – over the past six years during a period of steadily increasing earnings and almost constant dividends. Investors also receive greater flexibility as they can choose when to receive their payoff to best suit their particular circumstances. Figure C6.5 further depicts Intel's circumstances and the market's reaction to them, again reinforcing the reduced effect of dividends on share price.

Table C6.2 Intelligent distribution? How Intel has returned cash to its shareholders ($m)

RESULTS: GREATER PRESSURE FROM SHAREHOLDERS TO CONDUCT BUYBACKS

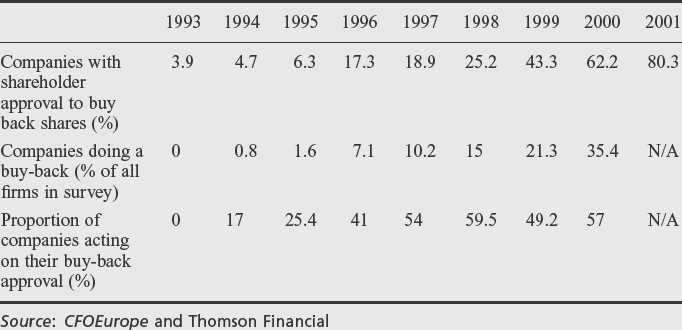

The benefits of buyback schemes have not gone unnoticed by investors who have increasingly voted to let company managers undertake share repurchases. (See Table C6.3.) It would appear also that this sentiment has been heeded by Europe's largest companies as the percentage of companies acting on their buy back approval has risen consistently over recent years.

Figure C6.5 In the chips. Intel's share price bears no relation to its dividend payments.

Source: corporateinformation.com

Table C6.3 The greenlight. The number of companies with shareholder approval to buy back shares, and the number that have completed a repurchase (%)

In light of such dependable shareholder approval of buyback schemes, it appears management may often have sought approval with little or no intention of acting on it. Instead managerial motivation may have been driven by the luxury of having an additional distribution avenue should market conditions alter significantly, investment opportunities run dry or merely because competitors had similar approvals in place.

Today however, either due to shareholder weariness of such managerial procrastination or due to greater corporate acceptance of the benefits of buyback schemes, companies are more likely than not to act on their buyback approval. Indeed the proportion of companies implementing repurchase programmes once approval is in place has been steadily growing.

CAVEATS

Several legimate arguments could be made to water down some of our conclusions

a) The changes in legislation enabling buybacks have only been implemented recently. It is feasible, therefore, that the rapid acceptance – and completion – of buybacks has been fuelled more by one off restructuring of corporate balance sheets than by the desire to fundamentally alter the way in which companies return cash to their shareholders.

b) The study period for this research was a period of significant economic growth and healthy corporate profits. Under such conditions managers may have a greater requirement for the flexibility offered by share repurchase schemes. Under this proposition, the trend towards greater buyback activity depicted in this survey may not continue uniformly into the future but instead adopt a cyclical pattern. It is then possible that, as the current economic uncertainty lingers and a potential recession sets in, our findings are reversed and traditional dividends make a resurgence at the expense of the newly implemented re-purchase programmes.

c) As suggested in this paper, one of the most attractive attributes of buybacks is flexibility. This flexibility, however, may not last forever. If the current trend for buybacks to grow in importance does indeed continue, investors may begin to expect buybacks in the same way that their predecessors expected dividends. Such an eventuality would suggest that eventually buybacks may adopt a similar signaling power to that previously enjoyed by traditional dividends. This implies that any buyback reduction would signal poor recent corporate performance and reduced future potential, leading to a lower share price.

A CFO Europe Research Report (2001).