13

Learning to Live with Fixed Rate Mortgages

An Evolutionary Approach to Risk Management

Martin Upton

BACKGROUND

Until the late 1980s fixed rate mortgages were a rarity in the United Kingdom. In the current world of personal financial services, though, they have now become a commonplace offering from the mortgage lending industry. In recent years they have accounted for a third of new mortgage lending with the bulk of the business being in shorter term products with rates fixed for one to five years.

In a highly competitive market the rates offered have afforded the lenders narrow margins over the cost of borrowing. Yet despite this competitive environment the fixed rate mortgage market has attracted interest and criticism from politicians and other observers culminating in the Miles Report on “The UK Mortgage Market: Taking a Longer-Term View” published in April 2004.

This article explains the development of the fixed rate mortgage market in the UK, the risk management and margin implications for the lenders, the potential future development of the market in the wake of the introduction of CAT standards for mortgages and the publication of the Miles Report, and the issues for mortgage lenders arising from the application from 2005 of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS).

THE MORTGAGE WORLD BEFORE FIXED RATES

Until the late 1990s the vast majority of mortgage lending was undertaken by the building societies – mutual organisations owned by their savers and mortgagors. Until 1984 a cartel led by the major building societies and operated through their trade association, the Building Societies Association (BSA), set the levels for mortgage and savings rates, effectively guaranteeing their net interest margin. These rates were known as “administered” rates – meaning that the rates were set by the societies themselves rather than in accordance with an official or reference rate. Changes to rate levels were agreed by the cartel, normally only after changes to UK official rates. Whilst some variability around the cartel rates was applied by societies – for example to adjust the rate charged for larger loans – the business environment was essentially non-competitive in price terms. In so far as there was competition it was confined to fighting for market share via advertising and through the presence of branches in the high streets. The liberalisation of financial services in the 1980s ended these practices and heralded a competitive multi-product mortgage market in the UK.

Virtually all mortgage lending until the late 1980s was on an (“administered”) variable rate basis. Fixed and capped rate lending was conspicuous by its absence. Why was this?

The answer is that, with the majority of building society funding coming in the form of variable rate retail deposits, there was also little structural incentive to offer fixed rate mortgages. Until the mid-1980s there was also no wide scale availability of hedging products like interest rate swaps for institutions to manage the risks of offering fixed rate mortgages. Indeed, until the Building Societies Act of 1986 came into effect societies had, in any case, very limited powers to enter into derivative transactions. Societies additionally had to await the publication of Statutory Instrument (SI 1988 No. 1344), which advised on the hedging contracts they were permitted to use, and the Building Societies Commission's Prudential Note (1988/5) on “Balance Sheet Mismatch and Hedging” prior to developing their use of derivatives. In such circumstances it was hardly surprising that fixed rate offerings were not a feature of the mortgage market.

THE EMERGENCE OF FIXED RATE MORTGAGES

The development of the fixed rate mortgage market from the late 1980s can be ascribed to a number of concurrent developments.

Firstly, and most importantly, the 1986 Building Societies Act together with SI 1988 1344 gave the sector the power to use derivatives for hedging purposes. The wording, in Section 23 of the Act, was not the most helpful since it required each new transaction in derivatives by a society to be:

… for the purpose of reducing the risk of loss arising from changes in interest rates, currency rates or other factors of a prescribed description which affect its business. (Building Societies Act 1986 23(1))

At the very least societies had to initiate audit trails to prove compliance with this rule. Failure to provide such a link to “loss reduction” would have meant that the use of the derivative was “ultra vires” – outside the powers of a building society.

With fixed rate mortgages, it was in any case relatively easy for societies to prove (with or without legal opinions) that entering into an interest rate swap to convert the fixed rate flows from a fixed rate mortgage asset to variable rate flows to match the variable rate funding that supported the mortgage loan was a manifest process of risk reduction. Consequently the terms of the 1986 Act did not inhibit the emergence of fixed rate products in the late 1980s.

Section 23 was, in any case, amended by Section 9A of the 1997 Building Societies Act. Derivatives could still only be used for risk management purposes (and not for trading) but a “safe harbour” was allowed whereby failure to achieve risk reduction did not make the contract entered into ultra vires. This amendment was designed to give comfort to the financial counterparties to derivatives transactions with building societies. Societies were no longer at risk of entering into unenforceable derivatives contracts through failure to comply with Section 23 of the 1986 Act. The comfort this provided to the industry and financial counterparts was material particularly in the wake of the House of Lords' judgement in 1991 on the use of derivatives by UK local authorities which declared such contracts entered into by the authorities ultra vires and, hence, unenforceable.

Secondly, the growth of commercial banks' activity in the mortgage market impacted on the scale of fixed rate lending. With no legal restrictions on their use of derivatives and with more fixed rate liabilities on their balance sheets, the banks had greater flexibility to engage in fixed rate lending than building societies. This meant that the building society industry had to follow or lose market share.

The growth in the banks' fixed rate mortgage market share was, in any case, subsequently inflated in the mid-1990s by the decision of five major building societies (Halifax, Alliance & Leicester, Woolwich, Bradford & Bingley and Northern Rock) to follow the lead of Abbey National in 1989 and convert to banking status. This led to a sharp reduction in the size of the building society sector and its share of the mortgage market. The shift in sectoral share was accentuated by Halifax's merger with Leeds Permanent Building Society in 1995, two years prior to conversion to banking status; by the acquisition of Cheltenham & Gloucester Building Society by Lloyds TSB in 1995; by the acquisition of National & Provincial Building Society by Abbey National in 1995; and by the acquisition of Bristol & West Building Society by the Bank of Ireland in 1997.

Thirdly, the particular interest rate characteristics of late 1980s and early 1990s – high nominal (and real) interest rates and an inverted yield curve – provided an opportunity to market fixed rate mortgages successfully. With the standard variable rate for mortgages rising above 15% per annum, borrowers were keen to seek out products which mitigated this punitive rate for borrowing. The inverted yield curve meant that fixed rate products, priced by reference to the interest rate swap rates for the same fixed rate term, could be offered at a lower rate than variable rate mortgages. In 1990, some five-year fixed rate mortgages were offered at rates 3% per annum lower than standard variable rate alternatives. Unsurprisingly mortgagors were keen for fixed rate products which immediately offered a material reduction in their borrowing costs.

Witnessing this development, it certainly appeared that the key driver of the emergence of the fixed rate market was the consumer. The preceding fifteen years had seen significant volatility in UK rates and three periods when variable mortgage rates were higher than 14% per annum. Consequently products which provided cost certainty were easy to sell – particularly for those whose mortgage costs represented a high proportion of household expenditure. If you could also secure (at least temporarily) a cut in cost by switching from variable to fixed rate – as indeed you could in the early 1990s – then the appetite for fixed rate mortgage products was reinforced. Once the lenders had seen the market potential, the product offerings became – and have since remained – profuse. The extent of the competition has placed downward pressure on the pricing of fixed rate mortgages, thereby further helping to sustain the attractions of the product to borrowers.

The margins secured on fixed rate mortgages have normally been lower than on standard variable rate business. The lenders have, though, been reluctant to step back from fixed rate lending, partly because of a fear of reducing their share of new lending – always an important performance indicator for lenders. Primarily, though, lenders see the tight margins on fixed rate lending as a price that has to be paid to get customers through the door, at which point other products can be sold to them – including further mortgage products when the initial fixed rate deal matures.

Table 13.1 Interest rates 1988–1992

| Year | Average base rates (%) |

| 1988 | 10.3 |

| 1989 | 13.9 |

| 1990 | 14.8 |

| 1991 | 11.5 |

| 1992 | 9.4 |

| Source: www.houseweb.co.uk/house/market/irfig.html (accessed 20 July 2005) | |

Table 13.2 Fixed rate lending 1993–2004

| Year | Fixed rate lending as % of total lending |

| 1993 | 45 |

| 1994 | 42 |

| 1995 | 23 |

| 1996 | 17 |

| 1997 | 35 |

| 1998 | 50 |

| 1999 | 36 |

| 2000 | 29 |

| 2001 | 27 |

| 2002 | 23 |

| 2003 | 36 |

| 2004 | 29 |

| Source: www.cml.org.uk/servlet/dycon/zt-cml/cml/live/en/cml/xls_sml_Table-PR3.xls (accessed 20 July 2005) | |

Since 1992 the volume of fixed rate lending has ranged between 17% and a peak of 50% of new lending, the share being largely driven by the relative levels of fixed rate and variable rate mortgages – the lower the fixed rates relative to variable, the higher the fixed rate share of the total market.

RISK MANAGEMENT ISSUES

Selling fixed rate mortgages gives rise to a number of risk management issues for lenders.

An important initial point to make, though, is that in the UK market the fixed rate period normally only applies to the first few years of the full term of the mortgage. For example, mortgagors may enter into a mortgage repayable over twenty-five years with the mortgage rate fixed initially usually for a term of up to five years. At the end of this fixed rate term, the mortgage typically reverts to a variable rate unless the mortgagor opts for a new fixed rate term (or indeed another mortgage product, e.g. a capped rate mortgage). The hedging requirement for the lender therefore relates to the initial term only and not the full potential term of the mortgage.

Interest Rate Risk: Hedging to Variable Rate

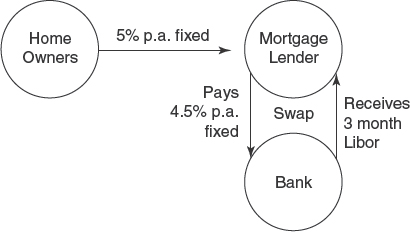

When it is necessary to hedge fixed rate mortgages, the basic mechanism is to use a simple interest rate swap, with the lender paying fixed rate for the term of the fixed rate mortgage and receiving the variable rate – typically three month libor (see Figure 13.1). The net result is that lenders end up with an asset yielding a fixed margin (the difference between the swap and mortgage rates) over Libor. Standard practice is to hedge the entire tranche size which is being offered although some providers have used an amortisation schedule reflecting the fact that, subject to interest rate movements, some prepayment of fixed rate mortgages occurs prior to the end of the fixed rate term.

Figure 13.1 Typical fixed rate mortgage swap

To reflect the time at which a customer draws down on a mortgage commitment (particularly if a house move is involved) it is sound practice to arrange for a forward start for the swap (typically three months forward). Whilst this makes for sound risk management, it does mean that the mortgage lender is signaling to the swap market makers which way round they are at the point of quotation and indeed the exact structure may identify the name of the mortgage lender to the swap market. In mitigation of the risk this poses to obtaining a fair price is the huge liquidity in the sterling interest rate swap market and the large number of banks prepared to quote on tight bid-to-offer spreads.

One observation which may be made is why mortgage lenders do not make more use of the “internal” hedges available to them by the simultaneous offering of fixed rate savings bonds to their customers. Clearly putting a, say, two-year bond against a two-year fixed rate mortgage product eliminates the need to use the derivatives market to hedge either. The reality is, though, that the market for fixed rate mortgages is, and always has been, huge relative to that for fixed rate bond products. There is a particularly limited appetite for fixed rate bonds with a term of more than two years, reducing further the scope for internal hedges of longer term fixed rate mortgage products. The reasons for the lack of appetite for fixed rate bonds are unclear but may be related to the requirement with most products for the investor to pay a financial penalty for access to the funds invested ahead of the maturity term.

One alternative “set off” against the fixed rate mortgage applied by several lenders in the 1990s was to reduce the holdings of gilt-edged stocks in their liquidity investment portfolios, switching the funds realised into variable rate products. This eliminated the need to swap fixed rate mortgages since the lenders effectively had one set of fixed rate assets (gilts) replaced by another (fixed rate mortgages), leaving the balance sheet interest rate risk position largely unchanged. The sheer scale of fixed rate mortgage business during the early 1990s meant, however, that this hedging option became exhausted for many lenders.

The one-sidedness of the use of the swap market to hedge mortgages results in another problem – that of the credit exposure. Mortgage lenders find that their swap portfolios are dominated by swaps where the fixed rate is being paid. If interest rates fall, these exposures grow in market value (or replacement cost) to the swap provider and on this “marked to market” basis the swap provider's exposure to the mortgage lender rises. This has created situations where swap providers have declared themselves full on their credit limit to mortgage lenders.

The extent of the impact on exposure can be shown as follows: suppose a bank has £1bn (notional) of five-year swaps outstanding with a mortgage lender. If the contracted rates match market rates, the NPV of this exposure is zero. The bank would, however, mark some exposure against the credit line for the mortgage lender to allow for risk of future rate movements – perhaps of the order of 5% of the notional principal (£50m). If rates fall by 2% per annum, however, the value of the contracts to the bank rises by the NPV of 2% per annum for five years on £1bn (notional). This amounts to £87m if yields are 5% per annum, raising the total exposure against the mortgage lender to £137m – since £50m would still be added to allow for further rate movements. At such exposure levels the bank's credit division may stop further new business being written with that mortgage lender.

Scope to mitigate this position does now exist through the growth in swap collateralisation arrangements whereby the swap provider is provided with either cash or bond collateral from the mortgage lender to reduce the outstanding net credit exposure and open up the credit line again for further derivatives business. The continued development of the credit derivatives market could also provide a further avenue for swap providers to reduce their exposure to counterparties.

Basis Risk and Impact on the Net Interest Margin

The usual hedge for fixed rate mortgages does leave lenders with a basis risk issue. Variable rate flows are linked to Libor and not (usually) base rates. Three-month Libor rates can be higher or lower than base rates particularly during periods when movements in base rates are anticipated by the markets. It is not uncommon to see Libor circa 20–25 bps above or below base rates under such circumstances. Why does this matter?

The hedge of a fixed rate mortgage converts the fixed rate asset to variable rate to match to variable rate funding. For many mortgage lenders – particularly the building societies – funding is in the form of retail flows where rate movements are largely related in timing and size to base rate movements. Few lenders have an appetite to alter these “administered” rates without the “cover” of a base rate move given the fear of adverse coverage in the media. The upshot is that in times of falling rates Libor falls below base rate often for a sustained period and the synthetic earnings from a swapped fixed rate mortgage asset fall. This reduction in earnings cannot be recouped since the cost of funding cannot be reduced until the expected base rate rise materialises.

Whilst the issue may appear to be a minor risk to the mortgage lender the reality is that the cost can sometimes be material. If 30% of all mortgage assets are on fixed rate the full year impact of Libor consistently 25 bps below base rate is a reduction in the net interest margin of 8 bps. This represents a circa 6% drop in net interest income for an average building society (given that the interest margin for societies ranges between 120 bps and 160 bps). The percentage reduction is, however, less for the banking sector where margins are significantly wider. This is due to the fact that banks, unlike the mutual building societies, need additional profits to fund their dividend payments to shareholders.

Mitigation of this basis risk can be achieved by using the market for base rate swaps – either by swapping to base rate instead of Libor in the first instance or arranging Libor to base rate swaps. There are, though, two problems with this: firstly the base rate swap market is not huge and has limited liquidity since swap providers have difficulty covering the positions that arise through putting such swaps onto their books. Secondly, if Libor rates are, or are expected to fall, below base rates the market will reflect this in the swap price (e.g. 3 month Libor received against base rate less 10 bps paid) with the result that the loss arising from the basis risk is, at least in part, crystallised through this swap arrangement.

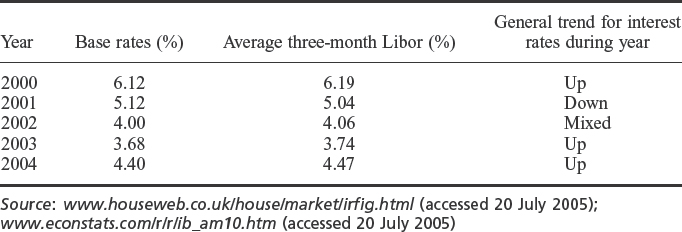

Table 13.3 Base rates and average three-month Libor 2001–2004

The consequence is that in most cases lenders carry this basis risk and accept (or hope) that in complete interest cycles the losses when rates are falling (and Libor rates are below base rates) are offset – as Table 13.3 implies – when rates start their upward path (with Libor rates rising above the prevailing base rates).

Sales and Hedging Mismatches: “Attrition Rates” and “Balloons”

Lenders are exposed to interest rate risk whilst fixed rate mortgage products are being sold if, as is usually the case, the swap is arranged ahead of product sales. This risk materialises particularly if rates move sharply higher or lower immediately after the swap is arranged.

If rates move lower, the risk is that the mortgage products do not sell in sufficient quantities to match the swap size, with potential customers either holding back in anticipation of lower fixed rate products or defecting to those lenders who are offering a lower fixed rate (hedged by a lower swap rate). Lenders have two options if this happens: they can either lower the price of the mortgage product or withdraw the product and cancel the unwanted element of the swap. Both measures though effectively incur a cost either through a reduction in mortgage earnings or through the cancellation fee on a swap which has moved into loss in market value. Mitigation of this risk can be achieved through a number of techniques. Firstly, during times of volatile rates (particularly when they are falling) swap sizes can be kept lower than normal to ensure that there is less risk of large unsold tranches of fixed rate products. This approach is often unwelcome in the marketing departments and amongst sales staff who prefer to have some longevity in the sales period of products. Frequent repricing of products also incurs higher marketing costs. A second alternative requires the detailed analysis of sales records by the risk management divisions of lenders. By looking at past experiences of sales volumes and “attrition rates” (where commitments to borrow do not turn into actual mortgage assets as customers do not take up their mortgage option), the likely mortgage sales and drawdowns for a particular product can be estimated. Although not an exact science it can mitigate the worst of the risks arising from selling fixed rate products during a period of volatile market rates. A third hedging option is to buy the swaption (an option on a swap) rather than entering into the swap itself. The maximum downside to this transaction would be the cost of the swaption – potentially significantly lower than the write-off costs of a cancelled swap. If product sales materialise and the strike price is “in the money”, the swaption can be exercised in whole or part to match the actual mortgage assets taken onto the balance sheet. The downside of this hedging technique is, though, the cost of the option which will also become more expensive during those volatile periods for market rates (which is just when such protection from potential losses may be needed). The fixed rate mortgage market is, as noted earlier, very competitive and any additional risk protection costs may make a product unattractive to potential customers. Finally, attrition rates can be reduced if a commitment fee is paid by customers on securing (but before drawing down) the fixed rate mortgage. Although discouraged by the introduction of CAT standards for mortgages (see below), the payment of such an upfront fee can help prevent mortgage sales from failing to turn into mortgage assets.

A reverse set of problems arises if rates rise sharply after a product has been launched and prior to when it is withdrawn. In such circumstances customers advised by the media or their financial intermediary or even branch staff move in great numbers into fixed rate products with the risk that a “balloon” in sales occurs in the period immediately before a product is withdrawn (to be replaced by higher priced alternatives). The result can be that the swap size is exceeded by the product sales and the excess can now only be hedged at the prevailing market rate for the swap. This risk is reinforced by the fact that the attrition rate typically moves close to zero during an upward rate cycle. Containment of this risk can again be helped by good record keeping and risk management systems which can estimate just how large the “balloon” might be under these market conditions. The better alternative is to have effective reporting systems (to provide an up-to-date record of actual sales) and fast closedown procedures to withdraw products at short notice. The problem with the latter approach is that it may expose a culture conflict within the mortgage lender: the treasury division will want to see sales stop before a “balloon” gets oversized whilst the sales-driven branches (and intermediaries) who inevitably will want to be seen to be doing the best for their customers will be anxious to carry on selling even whilst the shutters are coming down on a product. Sales of products after their closing date are certainly not unheard of! Such issues represent excellent examples of the operational risks that exist within financial services firms.

Prepayment Risks

In the aftermath of sterling's suspension from the membership of the ERM in September 1992, UK interest rates fell sharply. Given that monetary policy no longer had to be set to ensure sterling's compliance with the designated exchange rate band (DM2.78 “floor” to DM3.12 “cap” around the DM2.95 mid-point) interest rates were able to fall to stimulate what was, in 1992, an economy in recession with the housing market experiencing falling prices in many areas of the country.

This sharp reduction in long and short term rates gave lenders of fixed rate mortgages their first material experience of prepayment risk. Borrowers who had taken out fixed rate mortgages – particularly the longer term fixes of five years and beyond – found that it was financially attractive to prepay the mortgage, even if this incurred prepayment costs, and refinance at the prevailing lower rates. Growing encouragement to take the refinancing route came from the financial intermediaries in the mortgage market who clearly saw increasing turnover on the mortgage market as enhancing their fee income. The intermediaries were able to advise the less sophisticated mortgagors how to add the prepayment penalties on redemption of the original mortgage to the new mortgage at the prevailing lower rate. Given how far rates had fallen the mortgagors still achieved a financial saving – which by implication meant that the lenders were losing money through this refinancing activity.

The standard protection to this interest rate risk applied by mortgage lenders was typically a flat rate prepayment charge of three or six months' interest (based on the original fixed rate). This clearly made prepayments unattractive if rates only moved slightly lower over the term of the mortgage but was insufficient to provide a defence against the quantum fall in rates that occurred both between 1991 and 1994 and between 1999 and 2003.

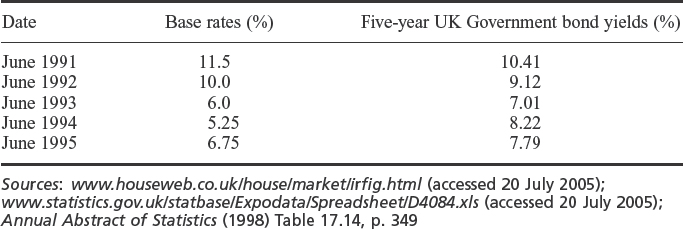

Table 13.4 Base rates and five-year gilt-edged stock yields 1991–1995

For example a 12.5% per annum five-year fixed rate mortgage taken out 1991 and then refinanced at 8% per annum in 1993, with a penalty of six months' interest paid by the mortgagor, would have resulted in the lender losing (in undiscounted terms): 3 years × 4.5% of interest less the 0.5 years × 12.5% penalty payment received: a total (pre-tax) loss of 7.25% of the principal sum.

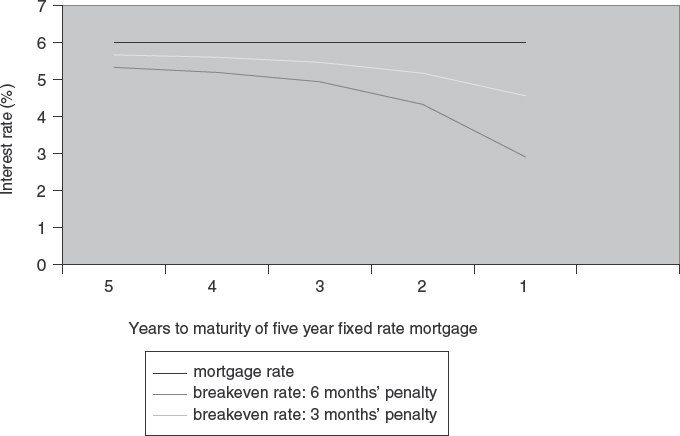

Figure 13.2 depicts the degree of protection provided by repayment penalties of six months and three months on a five-year fixed rate mortgage at 6% per annum. In both cases, the breakeven line for the mortgagor to pay the penalty and refinance for the residual period of the five years is depicted. The breakeven points assume there are no other costs incurred on refinancing: since in reality some costs are likely to be incurred, the actual “breakeven” interest rate may be a little lower than those shown. The figure demonstrates that the greatest vulnerability to prepayment risk occurs if rates fall sharply soon after a fixed rate mortgage has been drawn down by the mortgagor.

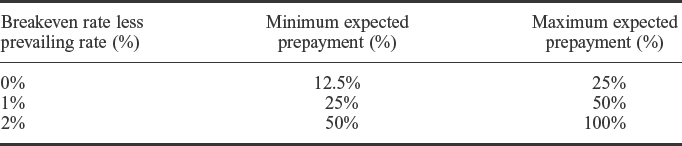

Realisation of the risks arising from prepayment made some mortgage lenders review their risk assessments and policy. Aided by growing dossiers on prepayment activity under different interest conditions, risk managers were able to forecast with some accuracy the volumes of fixed rate mortgages that would be prepaid. The assessment was not a simple economic matter as most borrowers would need to see sufficient financial daylight between prepaying/refinancing and staying with their existing mortgage deal before taking action. This reflects a mixture of customer inertia and the peripheral financial costs of moving a mortgage (legal fees, etc.). Elsewhere, though, prepayments do result from personal as opposed to financial circumstances (e.g. marriage breakdown) and these factors have to be factored into the analysis. Building on the assumptions of the potential cost under differing economic conditions it is possible to consider the policy alternatives for covering the exposure to prepayment risk not hedged by prepayment penalties. Table 13.5 provides an example of prepayment propensity rates applied by one mortgage lender in the UK.

Figure 13.2 Refinancing a five-year fixed rate mortgage

Where exposure is deemed to be material and potential, the policy that can be adopted is to buy options cover. This can take various forms. “Bermudan” options give the mortgage lender the right to receive the fixed rate originally paid to hedge the relevant mortgage tranche for the residual term of the fixed rate period. To exercise this option the lender pays an exercise fee amounting to the value of the prepayment penalties due from the borrower on prepayment of the fixed rate mortgage. Clearly it only makes financial sense for the lender to exercise these options if rates had fallen to the point beyond that amount covered by the prepayment penalty. To reflect the fact that prepayment activity occurs at a rate over a period of time (i.e. it is not instantaneous for all cases where it makes sense for the borrower to refinance) the options should ideally be exercisable regularly (e.g. each month) enabling this hedging cover to track the actual pace of prepayment. These options do have some particular issues: firstly, such tailored options are only offered by a handful of market makers and consequently tend to be expensive – thereby pushing up the overall cost of hedging. Additionally, their esoteric nature makes them difficult to value (a matter compounded by their illiquidity). An alternative is to buy standard interest rate floors (which pay out to the buyer automatically if market rates fall below the strike rate of the contract) to hedge the “tail” of prepayment risk. Whilst such options do not provide an exact hedge for the risk – particularly as the returns from the contract are linked to money market rates and not to the levels of swap rates which would primarily influence prepayment activity – they are sufficiently effective to cover most of the residual interest rate risks on prepayment.

For some lenders protection against prepayment is achieved simply by requiring borrowers to pay a penalty linked to market rates. This “marking to market” of penalties extinguishes the interest rate risks arising from prepayment. Its downside is the impact on the company's profile with the public, with some customers finding that this approach either leaves them locked in to a high fixed rate deal or forced to pay a large penalty to exit from it.

Table 13.5 Example of forecast prepayment propensity rate

Policy towards prepayments in the UK varies starkly with that overseas – and particularly with the United States. Here mortgages are placed into pools, securitised and sold to investment funds. The mortgagors normally pay no penalties if they prepay one loan and move to another – which clearly invites them to do just that in a falling rate environment. The costs of prepayment are also not borne by the mortgage lenders as can be the case in the UK. The costs fall instead on the investment funds which find that the mortgage-backed securities they have bought “pay down” more quickly than expected (due to the prepayment of the underlying mortgages) leaving them to reinvest in new securities. These new investments, will, of course, be at lower yields in the falling rate environment which has generated the prepayment activity!

CAT Standards

In 2000, as part of the move by the Government and the FSA to move towards the regulation of the mortgage market, CAT (“Cost”, “Access”, “Terms”) standards were introduced to the mortgage market.

For fixed rate mortgages the CAT standard includes:

- A maximum reservation fee of £150.

- A maximum prepayment penalty of 1% for each remaining year of the fixed rate mortgage, reducing monthly.

- No prepayment penalties after the end of the fixed rate period.

- No prepayment penalty if the mortgagor moves house and stays with the same lender.

Potentially these restrictions on the size of the reservation fee and on prepayment charges expose lenders to more interest rate risk by increasing the risk of mortgage commitments not turning into mortgage drawdowns and by increasing the likelihood of prepayment activity at the lenders' expense.

The alternative would be to hedge the enlarged risks by the increased use of options, although this would either impact on the headline rate of the mortgage or on the net margin achieved by the lender.

The outcome, though, has been softened by the decision to make the standards for mortgages voluntary. Consequently, even customer-orientated lenders like the Nationwide Building Society have felt able, after a period, to dispense with the CAT standards. Future mortgage regulation could, however, revisit these issues and make standards mandatory.

The Miles Report

A further recent development to the fixed rate market came with the report by Professor David Miles on “The UK Mortgage Market: Taking a Longer-Term View”. This report had been commissioned by the Treasury and was published in April 2004.

One of the particular areas of focus was why long term fixed rate mortgages were largely nonexistent in the UK market compared with their prevalence in the USA and their existence in certain parts of Europe (e.g. Denmark).

The reality of the fixed rate market, as the report highlighted, is that it is dominated by one-, two- and three-year fixed rate deals. These can be priced lower than longer term deals for two reasons: firstly the UK yield curve since 1992 has predominantly been positive so the swap rate to hedge a 10-year or 25-year fixed rate deal is higher than for a shorter term product. Secondly the risks associated with selling longer term fixed rate products are enhanced both in circumstances where products do not sell and in the case of prepayment. A hedge on an unsold tranche of a 25-year mortgage product is much more costly to unwind than, say, an equivalent two-year product for the same adverse move in the yield curve. Hedging these risks inevitably puts upward pressure on the rate sought by lenders on long term fixes and, thereby, discourages customer appetite. The situation is not the same where lenders securitise the mortgages sold and sell the resultant mortgage backed securities to investors – a practice, as noted above, which is the norm in the United States. Here the bond investors take the prepayment risk and so there is no need for the lenders to hedge it. The result is that the rates on the long term fixed rate mortgages are therefore not inflated by hedging costs thus making the products more attractive to the public.

One further factor skews demand to the short term products. Lenders make assumptions when setting the fixed rate about the likelihood both of cross sales of insurance and other products to the mortgagor and of the chance that at the end of the fixed rate period borrowers will move to the lenders' standard variable rate product.

The earnings coming from these two sources can then be considered when deciding how keenly to price the rate on the fixed rate mortgage. For longer term products these enhanced earnings will be further away (in the case of conversion to the standard variable rate) or the subsidisation effect of the cross sales will have to be spread over a higher number of years when setting the fixed rate on the mortgage.

The upshot is that the ability to price very keenly to attract demand is magnified for short term fixtures with the inevitability that this is where the customers gravitate to. The reality of the past decade is that the key driver when it comes to choosing first fixed over variable rate, and then between the alternative fixed rate products, is the “headline” rate – and the lowest rates have normally been seen in the very short term fixed rate mortgages. Indeed this pattern of behaviour by borrowers was commented on in the Miles Report which noted that borrowers attach enormous weight to the level of initial monthly payments when choosing between mortgage products.

IFRS and Fixed Rate Mortgages

From 1 January 2005, International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) were adopted by the member states of the European Union and a number of other countries globally. With common accounting standards being applied, the intended results include both greater transparency of company activities and an improved capability to make comparisons between companies.

This has impacted upon the mortgage lenders through one of the new standards – International Accounting Standard 39 (IAS) 39. This requires all derivatives contracts to be “marked to market” and for them to be reported at fair value on the balance sheet. This clearly has implications for mortgage lenders who, as has been explained, use interest rate swaps in huge volumes to hedge their fixed rate products.

The original proposals raised the prospect of the swaps and other derivatives that support fixed rate lending being revalued without a similar treatment for the mortgages they were hedging. This could have resulted in large movements in profitability being recorded since changes to interest rates would have caused the consequent profits or losses on the derivatives portfolio being taken to the profit & loss account without the offsetting movement in the valuation of the underlying fixed rate mortgages.

In recognition of the issues which this would cause, the finalised treatment of hedged items under IAS 39 allows for the application of “hedge accounting” where assets and liabilities are linked to derivatives contracts. The mortgage lenders must either demonstrate a clear and specific link between a mortgage asset and the derivative hedging it (“mini-hedge”) or must demonstrate, to a satisfactory degree of proximity, the general linkage of derivatives positions hedging a portfolio of assets (“maxi-hedge”). With the latter there may not be an exact, product-by-product, linkage between fixed rate mortgages and the derivatives hedging them. There needs, however, to be a close degree of relatedness (i.e. in the size and maturity of the mortgages and the linked derivatives) to obtain approval for hedge accounting treatment by the auditors.

The application of hedge accounting eliminates the risk of large swings in profitability arising from the revaluation of hedging transactions. It also reflects the true position that if the derivatives positions have fallen in value it is because the fixed rate mortgages they are hedging have risen in value and vice versa. Whilst providing a solution, the realities of hedge accounting have proved challenging for the mortgage lenders, particularly as a large volume of hedged products were sold well before the notion of “hedge accounting” for them was proposed. The larger lenders, who have typically hedged fixed rate products on a portfolio, rather than a product-by-product basis, have found the requirement to link derivatives to the underlying assets challenging – a problem that has been reinforced by the fact that the outstanding balances on fixed rate products do move lower during the fixed rate period due to capital repayments and prepayments.

The use of hedge accounting for fixed rate products does provide a rational assessment of the fair value of hedged mortgage assets. It does, however, place an onus on the mortgage lenders to maintain rigorous standards of documentation about the ongoing linkage of fixed rate mortgages to their supporting derivatives positions.

CONCLUSIONS

Analysing the development and growth of the fixed rate mortgage market leads to a number of observations about the risk management issues they generate for lenders.

Firstly, fixed rate mortgages reveal the potential for a culture clash within lending institutions. Customer-facing staff, particularly if business volumes are a key performance measure, will be motivated to sell products beyond the amount hedged by the treasury department. The consequence is that such “excess” sales volumes may result in financial losses being incurred.

Secondly, the structuring of products and the sales process risk ignoring (and thereby not pricing in properly) the embedded optionality effectively sold to the customer.

Where a customer commits to a mortgage for the payment of a small upfront fee, the lender has in effect sold them a cut price option. If interest rates move lower, the customer will be incentivised not to take up the option to drawdown that mortgage but to shift to a new, lower priced alternative.

Thirdly, the hedging of prepayment risk by the use of fixed penalty payments on redemption (e.g. six-months' interest) provides sufficient cover to lenders during periods of low interest volatility. These cannot provide sufficient protection to the lender when there are quantum moves in rates of the sort experienced by the UK in the 1990s. The exposed “tail” of prepayment risk is indeed an excellent example of the consequences of an embedded option sold (usually without charge) to the customer.

Fourthly, the impact on the profitability of lenders is likely to be adverse and the lower is likely to be the net interest margin, the greater the proportion of fixed rate products in the mortgage portfolio. Fixed rate mortgages are priced keenly and the growth of the market has diminished the size of the “back books” of the mortgage lenders – the stable holdings of mortgages on standard variable rates which normally generate the highest interest margins for lenders. Aided by the mortgage intermediaries becoming increasingly attuned to methods for maximising the turnover of mortgage deals – to their advantage in terms of fee generation from new sales – customers have slowly become more financially sophisticated and less loyal to a particular lender. The result is that increasingly customers move from one keenly priced product to another and the impact over time is to deflate the average margin of a mortgage portfolio.

But although customer behaviour has become more financially astute of late, the reality is that many borrowers still have a less than full appreciation of interest rate risk. The take-up of the products with the lowest rate, regardless of the term of the fixture and seemingly without any assessment of future rates, has been a feature of customer behaviour. The evidence of prepayment activity falling well short of that justified by the economics (to the relief of lenders!) has further supported the view that a significant proportion of customers are still not financially adept.

THE FUTURE

Fixed rate mortgages are here to stay. The likelihood is that, despite any market developments which emanate from the final Miles Report, the focus of demand for fixed rate mortgages will remain in shorter term products. Indeed this product area has in recent years become the battleground where lenders have fought most aggressively for market share.

When mortgage lenders first offered fixed rate products it was seen by some as simply adding a product line to their mortgage offerings. Fifteen years on from the birth of the fixed rate era, the proliferation of products and the keenly priced terms on which they are written are threatening to reduce the profitability of the UK mortgage lenders whilst continuing to present challenging risk management issues to their treasury teams.

REFERENCES

Building Societies Act 1986 (Chapter 53). HMSO.

Building Societies Act 1997 (Chapter 32). The Stationary Office.

“Balance Sheet Mismatch and Hedging” Prudential Note 1988/5: Building Societies Commission.

CAT Standards for Mortgages

http://www.hmtreasury.gov.uk/documents/financial_services/mortgages/fin_mort_catstand.cfm (accessed 8 December 2005).

Miles, D. 2004. “The UK Mortgage Market: Taking a Longer-term View: Final Report and Recommendations.” The Stationary Office.