Every project is different. Different schedules, different products, and different people are involved. And, on any given project, the various stakeholders may have differing ideas about what the project is about. Your job, as project manager, is to make sure that everyone involved understands the project and agrees on what success will look like. The term project rules is not in any project management text or glossary. But clarifying the rules of the game for a new project is exactly what skilled managers need to do. And before they can communicate these rules to the players, they must be absolutely sure of them themselves. As in any new game, a project manager might ask: Who is on my side? How will we keep score? What is the reward? Seasoned project managers know that a new project can be as different from its predecessor as ice hockey is from gymnastics.

The need for project rules is part of the challenge of each new project. Since each one is different, you have to re-create the basic roles and processes of management every time a project begins. A close parallel is what happens in a reorganization of a company. After a reorg, the typical questions are: Who is responsible for what? How will we communicate? Who has authority? If these questions are not answered, the organization will fall apart; the same holds true for projects.

Remember the five project success factors? These were defined in Chapter 1 and include agreement on goals, a plan, good communication, scope control, and management support. No less than three of these crucial factors are dependent on a careful writing of the project rules:

Agreement on the goals of the project among all parties involved

Control over the scope of the project

Management support

This chapter looks at how to create project rules that will address these three factors. All project management activities flow from and depend on these rules, which is why there must be general acceptance of the project rules before the project begins. All the stakeholders—project team, management, and customer—must agree on the goals and guidelines of the project. Without these documented agreements, project goals and constraints might change every day. They are the guidelines that orchestrate all aspects of the project. Let's take a closer look at how a careful writing of the project rules can influence our three success factors:

Agreement on the goals. Getting agreement on project rules is rarely easy. This is because the views of all the stakeholders must be heard and considered. This give-and-take may be so time-consuming that some may push for moving on and "getting to the real work." This haste would be counterproductive, however. If the stakeholders can't come to agreement on the basic parameters of the project before the work begins, there is even less chance they will agree after the money begins to be spent. The time to resolve different assumptions and expectations is during this initial period before the pressure is turned up. One of the definitions of a successful project is that it meets stakeholder expectations. It's the job of the project manager to manage these expectations, and this job begins by writing them down and getting agreement. Project rules document stakeholders' expectations.

Project rules also set up a means by which the project may be changed in midstream, if necessary. This change management stipulates that the same stakeholders who agreed to the original rules must approve any change in the rules. (For more on change management, see Chapter 11.) The possibility of change emphasizes once again the necessity of having everything down on paper before the project begins. With this material in hand, the project manager will be well equipped to detail any effects that the changes might have on cost, quality, or schedule in an ongoing project.

Controlled scope. Because each project is different, each is an unknown quantity when it is started. This uniqueness adds to the challenge and fun of projects, but it can also lead to dramatic overruns in budgets and schedules. Later in the chapter, we'll look at several ways of avoiding these overruns by keeping the scope of a project clearly defined. A careful writing of the project rules is key in keeping the project team focused and productive.

Management support. It is a rare project manager who has sufficient authority to impose his or her will on other stakeholders. This is why a sponsor from senior management (as defined in Chapter 3) is a crucial factor in the success of a project. We will discuss how this management support may be written into the project rules. There are four methods to ensure that everyone understands, and agrees to, the project rules. The first, the project charter, is an announcement that the project exists. The following three, the statement of work, the responsibility matrix, and the communication plan, are developed concurrently and constitute the actual written documents containing the project rules.

Note

Note: As you read this chapter it will be helpful to refer to the downloadable forms found at the end of the chapter.

In the early 1970s a television show began each episode with Jim Phelps, ably played by Peter Graves, accepting a dangerous, secret assignment for his team of espionage agents. Sometimes on an airplane, other times in a restaurant or at a newspaper stand, Phelps received a plain manila envelope containing photographs and a cassette tape. After describing the mission, the voice on the cassette always ended with the famous line, "This tape will self-destruct in five seconds." We knew the extent of their risk because week after week the message was consistent: Phelps and his agents were working alone and, if caught, would not be assisted or recognized by the government of the United States. Dangerous, mysterious, and always successful, Mission: Impossible brought a new cold war victory every week.

With his committed team and detailed plans, Jim Phelps is a study in successful project management, with one exception—the Mission: Impossible team required complete secrecy and anonymity. No one could know who they were or what they were doing. Most corporate and government projects are exactly the opposite. Project managers don't need secrecy, they need recognition.

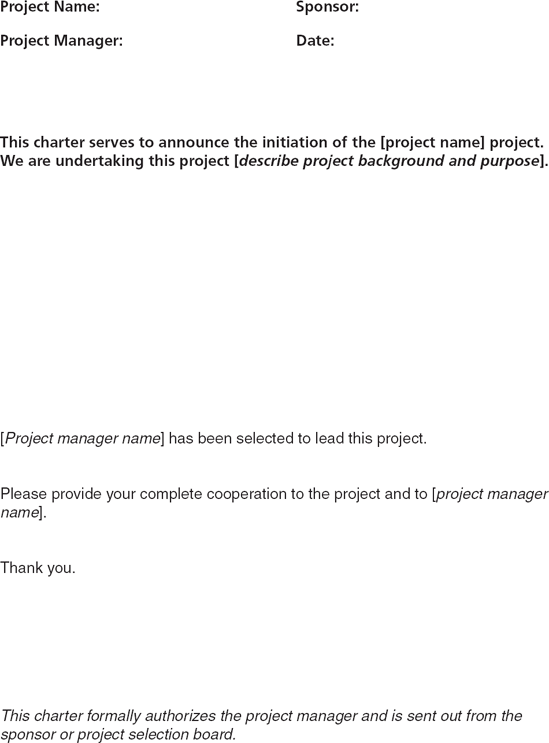

Because projects are unique and temporary, a project manager's position and authority are temporary. When a project begins, most of the people and organizations necessary for its success don't even know it exists. Without formal recognition, the project manager operates much like Jim Phelps, mysteriously and without supervision, but with far less spectacular results. That's why a project charter is so important; it brings the key players out into the open where everyone can see them.

A project charter announces that a new project has begun. The purpose of the charter is to demonstrate management support for the project and the project manager. It is a simple, powerful tool. Consider the following example.

During a major software product release, Sam, the project manager responsible for training over 1, 000 help desk workers, selected a printer to produce the custom training materials required for the project. This large printing order was worth more than $500, 000. After authorizing the printing, he was challenged by a functional manager who asked, "Who are you to authorize these kinds of expenditures?" (Sam is not a functional manager.) Sam responded by simply producing a charter and the statement of work for his project, signed by the program manager responsible for the entire release of the new product. "Any other questions?" he asked. "No. Sorry to have bothered you, Sam."

The charter clearly establishes the project manager's right to make decisions and lead the project.

A charter is powerful, but it is not necessarily complex. As an announcement, it can take the form of an e-mail or a physical, signed document. It contains the name and purpose of the project, the project manager's name, and a statement of support from the issuer. The charter is sent to everyone who may be associated with the project, reaching as wide an audience as practical because its intent is to give notice of the new project and new project manager. The simplicity of the charter can be seen in the downloadable charter form found at the end of this chapter.

Establishing Authority

From their positions of temporary authority, project managers rely on both expert authority and legitimate authority. Expert authority stems from their performance on the job; the better they perform their job and the more knowledge and ability they display, the greater authority they will be granted by the other stakeholders. Legitimate authority is the authority conferred by the organization. The project charter establishes legitimate authority for the project manager by referencing the legitimate authority of the sponsor. In the second of the preceding examples, Sam received authority from the program manager for his specific project. The charter said, in effect, "If you challenge Sam within the scope of this project, you are also challenging a powerful program manager."

Tip

Project Managers Need Expert Authority

Don't be misled by the power of the charter. Legitimate authority is important, but it is not sufficient. Project managers, like all leaders, lead best when they have established expert authority.

Tip

Getting the Right People to Sign the Charter

The charter establishes legitimate authority, so the more authority the signature has, the better, right? Not necessarily. If every project charter had the signature of the company president, it would soon become meaningless. The sponsor is the best person to sign the charter, because he or she is the one who will be actively supporting the project. The customer is another good choice for signing the charter. Every project manager would benefit greatly by a show of confidence from the sponsor and the customer.

Warning

Project Charter Can Have Two Meanings

There are two ways most firms use the term project charter. One is the way it is described here: as a formal recognition of authority. This is the way the Project Management Institute recognizes the term.[5] The other refers to the project definition document described in this chapter as a statement of work. Both uses will probably continue to be widespread.

The Charter Comes First

This chapter describes three techniques that document the project rules: the statement of work, the responsibility matrix, and the communication plan. All of these are agreements among the stakeholders. The charter, on the other hand, is an announcement, which makes it different in two ways. First, it should precede the other documents, because formal recognition of the project manager is necessary to get the agreements written. Second, it is not meant to manage changes that occur later in the project. The charter is a one-time announcement. If a change occurs that is significant enough to make the charter out of date, a new charter should be issued rather than amending the original.

Clearly documented and accepted expectations begin with the statement of work (SOW). It lists the goals, constraints, and success criteria for the project—the rules of the game. The statement of work, once written, is then subject to negotiation and modification by the various stakeholders. Once they formally agree to its content, it becomes the rules for the project.

Warning

The Statement of Work May Be Called by Different Names

This is one project management technique that, though widely used, is called by many names. At least half the firms using the term statement of work use it as it is defined in this book. Watch for these different terminologies:

The Project Management Institute favors project scope statement.

Contracts between separate legal entities will contain a separate statement of work for each project or subproject.

Some firms use the term charter instead of statement of work. This can be confusing because, as we have seen, this term has another common use in the project management vocabulary.

The term that an organization may use to describe the statement of work is ultimately unimportant. It is the content that matters, and this content must establish clear expectations among all stakeholders.

Audience

The statement of work is similar to a contract in that each is a tool that clarifies responsibilities and actions in a relationship. The difference is in the audience each one is aimed at. While a contract is a formal agreement between two legal entities, an SOW is directed solely at stakeholders from the same legal entity. To clarify:

When the customer and the project team belong to the same business, the SOW is the only project agreement required.

When the project team and the customer are different legal entities, there will be a formal contract between the two. If this contract is very large and is broken into several subprojects, the project manager may use an SOW for breaking the project into even smaller pieces and assigning them within the firm.

Warning

The Statement of Work Is Not a Contract

Although it is used to manage expectations and establish agreements, much like a contract, the statement of work as it is described here is not meant as a substitute for a contract.

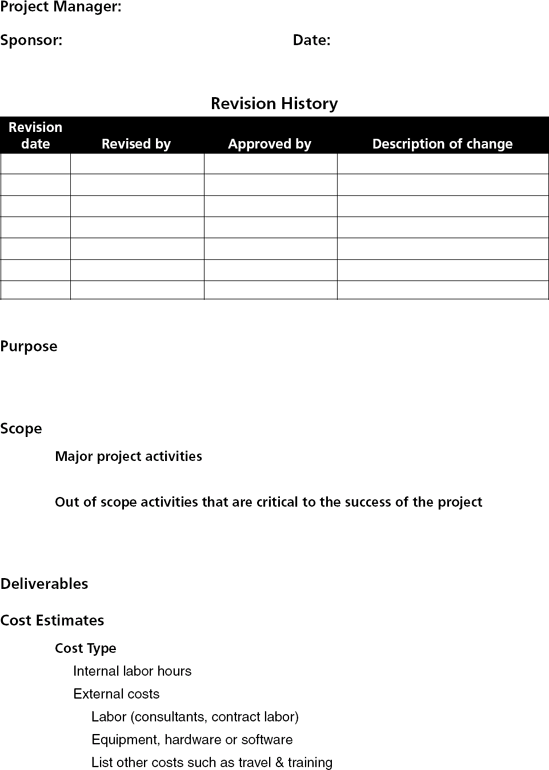

Many different topics may be included in a statement of work, but certain contents must be included. The downloadable form at the end of this chapter will help you create your own SOW.

1. Purpose Statement

Why are we doing this project? This is the question that the purpose statement attempts to answer. Why is always a useful question, particularly when significant amounts of time and money are involved. Knowing the answers will allow the project team to make more informed decisions throughout the project—and will clarify the purpose for the customer.

There may be many whys involved here, but the purpose statement doesn't attempt to answer them all. Neither the purpose statement nor the statement of work builds a complete business case for a project. That should be contained in a different document, typically called either a proposal, a business case, or a cost-benefit analysis. If there is a business case, reference it or even copy its summary into the SOW. The basic content of the business case proposal is addressed at the end of this chapter.

Tip

Purpose Statements Need to Be Clear

Avoid purpose statements like the following: "The purpose is to build the product as described in the specification document XYZ." "The purpose is to deliver the product that the client has requested." Neither of these statements explains why the project is being done, so they are useless as guides for decision making.

Here is an example of a good purpose statement from an information systems project:

The purpose of this project is to gather revenue data about our subsidiary. During the spin-off of the subsidiary, the finance group needs this information about the subsidiary's business in order to make projections about its future revenue. This data will come from the four months beginning June 1 and ending September 30. The finance group will be finished analyzing the data October 31, and won't need it afterward.

Notice that this purpose statement doesn't describe in detail what data is needed. That belongs in another document called the analysis document. Because the purpose statement was so clear, the team was able to make other decisions, such as producing minimal system documentation. The project team knew that the life of the product was so limited that it wouldn't require lengthy documentation meant for future maintenance programmers.

2. Scope Statement

Project scope is all of the work required to meet project objectives. Scope creep is one of the most common project afflictions. It means adding work, little by little, until all original cost and schedule estimates are completely unachievable. The scope statement should describe the major activities of the project in such a way that it will be absolutely clear if extra work is added later on. Consider the scope statement for a training project in Table 4.1. It's not as detailed as a project plan, but the major activities are named clearly enough to define what the project will and won't do.

Clarifying scope is more than just a fancy way of saying, "It isn't my job." All the cost, schedule, and resource projections are based on assumptions about scope. In fact, defining the limits of a project is so important that you will find boundaries being set in several different places besides the scope statement. The deliverables section of the statement of work and the work breakdown structure also set boundaries that can be used later to determine if more work is being added to the project. Even a product description such as a blueprint can be a source for defining scope and setting limits on scope creep.

Use the scope statement to define a project's place in a larger scenario. For instance, a project to design a new part for an aircraft will be a subset of the life cycle of the total product (i.e., the entire aircraft; see the discussion of projects versus products in Chapter 2). The scope statement is the correct place to emphasize the relationship of this project to other projects and to the total product development effort.

Tip

Specify What Is Beyond the Project's Scope

Be sure to specify what the project will not deliver, particularly when it is something that might be assumed into the project. Some activities may be out of the scope of the project but nonetheless important to successful completion. For example, in Table 4.1, 'Recruit trainers with subject-matter expertise" is obviously a necessary part of training development and delivery, but it is specifically excluded from the project by placing it in the list of activities "beyond the scope of the project."

Table 4.1. SAMPLE SCOPE STATEMENT

Project Management Training Rollout |

|---|

This scope statement is only one section within the project's statement of work. |

This project is responsible for all training development and delivery. Specifically, this project will: |

|

The following activities are critical to the success of the project, but beyond the scope of the project: |

|

Product scope can remain constant at the same time that project scope expands. If that sounds confusing remember that product scope consists of the features and performance specifications described in product design specifications. Project scope is all the work necessary to meet project objectives. For example, if an electrical contractor estimates the work on a job with the assumption that he or she will be installing a special type of wiring, the contractor would do well to clarify who is responsible for ordering and delivering the materials. Taking on that responsibility doesn't change the product scope, but it adds work for the contractor, so the project scope is expanded.

3. Deliverables

What is the project supposed to produce? A new service? A new design? Will it fix a product defect? Tell a team what it's supposed to produce. This helps to define the boundaries of the project and focuses the team's efforts on producing an outcome. Deliverable is a frequently used term in project management because it focuses on output. When naming deliverables, refer to any product descriptions that apply—a blueprint, for instance. Once again, don't try to put the product description in the statement of work; just reference it.

Realize that there can be both intermediate and end deliverables. Most homeowners don't have a blueprint for their house, but they get along fine without it. At the same time, no home buyers would want their contractor to build without a blueprint. The distinction lies in whether the deliverable is the final product that fulfills the purpose of the project—in this case, the house—or whether it is used to manage the project or development process, like a blueprint. Here are some other examples:

A document specifying the requirements of a new piece of software is an intermediate deliverable, while the finished software product is an end deliverable.

A description of a target market is an intermediate deliverable, while an advertising campaign using magazine ads and television commercials is an end deliverable.

A study of a new emergency room admissions policy is an intermediate deliverable. The actual new emergency room admissions process is an end deliverable.

It's important to note that project management itself has deliverables (as in the deliverables associated with each phase of a project life cycle, as discussed in Chapter 2). The statement of work can call for deliverables such as status reports and change logs, specifying frequency and audience.

Warning

Always Start with a Detailed Product Description

If there is no detailed product description, then creating one should be the only deliverable for a project. Trying to nail down all the important parameters, such as cost, schedule, resource projections, and material requirements, is futile if the product specification isn't complete, because the project team doesn't really know what they are building. Software product and information system projects are famous for committing this crime against common sense. It is premature to give an estimate for building a house before the design is complete, and it doesn't work any better in other disciplines. (For more on this problem see "Phased Estimating" in Chapter 8, and "Product Life Cycle versus Project Life Cycle" in Chapter 2.)

4. Cost and Schedule Estimates

Every project has a budget and a deadline. But the rules should state more than just a dollar amount and a date. They should also answer questions like: How fixed is the budget? How was the deadline arrived at? How far over budget or how late can we be and still be successful? Do we really know enough to produce reliable estimates? In addition, because cost and schedule goals have to be practical, it makes sense to ask other questions, such as: Why is the budget set at $2.5 million? Why does the project need to be finished December 31? Since one of the goals of making the rules is to set realistic expectations for project stakeholders, these figures must be realistic and accurate. (Any reasonable cost or schedule estimate requires using the techniques laid out in Part 3, "The Planning Process.")

Warning

Write It All Down!

Someone once observed that, when given a range of possible dates and costs, the customer remembers only the lowest cost and the earliest date. (How nice that the customer is such an optimist and has such great confidence in the project manager and his or her team!) That is exactly why it is so important to get all assumptions and agreements written down and formally accepted. The written statement of work is a much better tool for managing stakeholders than is memory.

What are the measures for success? If we produce the deliverables on time and on budget, what else does it take to be successful? Often, some important additional objectives are included in a statement of work. For example, on a project to replace a section of an oil pipeline, a stated objective was "No measurable oil spills," because the pipeline was in an environmentally sensitive area. When a department store chain installed a major upgrade to its nationwide inventory system, the stated objective was "Installation will not interrupt any customer interactions at the retail stores."

Objectives should be specific and measurable, so that they can provide the basis for agreement on the project. If the oil pipeline project had simply said, "The project will be executed in an environmentally sensitive manner," a project team would have no measurable guidelines. Instead it stated clearly, "No measurable oil spills," thus providing guidance for important decisions during the project.

Objectives can also measure outcomes. Measuring the success of an advertising campaign is not based solely on cost and schedule performance in developing it, but on the impact it makes on the target market. A stated objective might read:

Retail sales of our product will increase by 5 percent among 25- to 40-year-old females living in the San Francisco Bay area within three months of the beginning of the campaign, and by 10 percent after one year.

This objective won't be measured by the ad agency when the magazine ads and television spots are completed, but the customer will certainly be aware of it for the year after the campaign is initiated.

6. Stakeholders

In any statement of work, the project manager should identify anyone who will influence the project—that is, all the stakeholders. Stakeholders are described in Chapter 3. List the major stakeholders, what role they'll play, and how they'll contribute to the project.

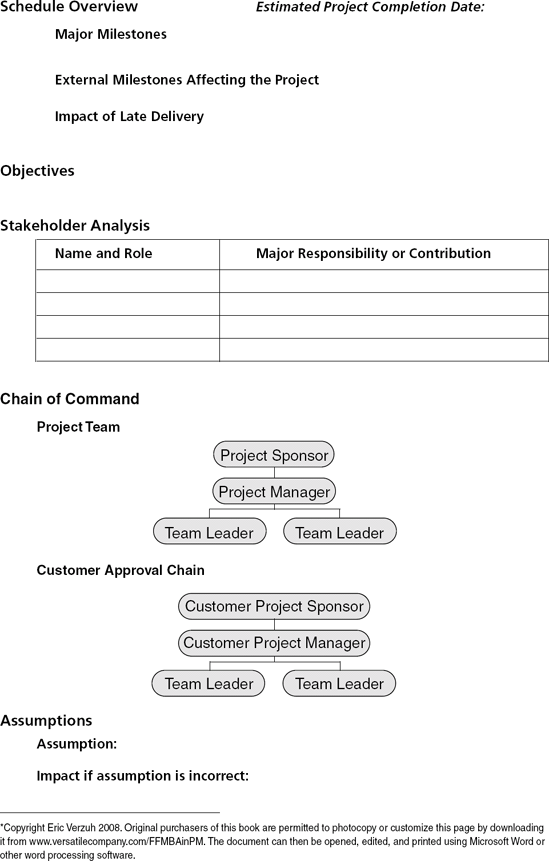

7. Chain of Command

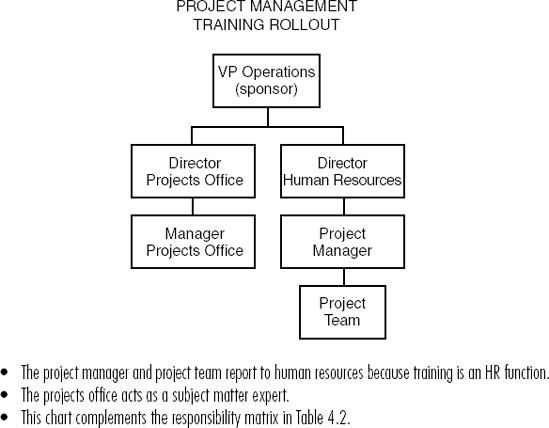

Who reports to whom on this project? A statement of work must make this clear. A common way to illustrate the chain of command is with an organization chart. The need for a defined chain of command becomes increasingly important as the project crosses organizational boundaries. Figure 4.1 is an organization chart for an internal project in which all the stakeholders report to the same person. It spells out who will make decisions and which superior to refer a problem to. Since customers also make decisions, it is often useful to include their reporting structure in the SOW as well.

Tip

Go Beyond the Minimum

After including all the necessary content listed here, be sure to add any other assumptions or agreements that are unique to this project. But be careful. Putting "everything you can think of" into the SOW will make it unmanageable. Remember that its purpose is as a tool to manage stakeholders.

Tip

Write the Statement of Work First

You, as project manager, need to write out the statement of work and then present it to the stakeholders. Even though you may not know all the answers, it is easier for a group to work with an existing document than to formulate it by committee. The stakeholders will have plenty of chances to give their input and make changes once the SOW is presented to them. (Experience has shown that after all the storm and fury of group discussion is over, you may find that as much as 80 percent of your document remains as you wrote it.)

Dealing with Change

The statement of work is a tool for managing expectations and dealing with change. Should there be disagreements once the project has started, these can often be solved by simply reviewing the original agreement. It is also true that the original agreements and assumptions may change during the course of a project. In this case, all stakeholders must understand and agree to these changes, and the project manager must write them into the SOW. The SOW that remains at the end of the project may be very different from the original document. The amount of this difference is not important; what is important is that everyone has been kept up-to-date and has agreed to the changes.

A statement of work answers many questions about a project, including the purpose, scope, deliverables, and chain of command.

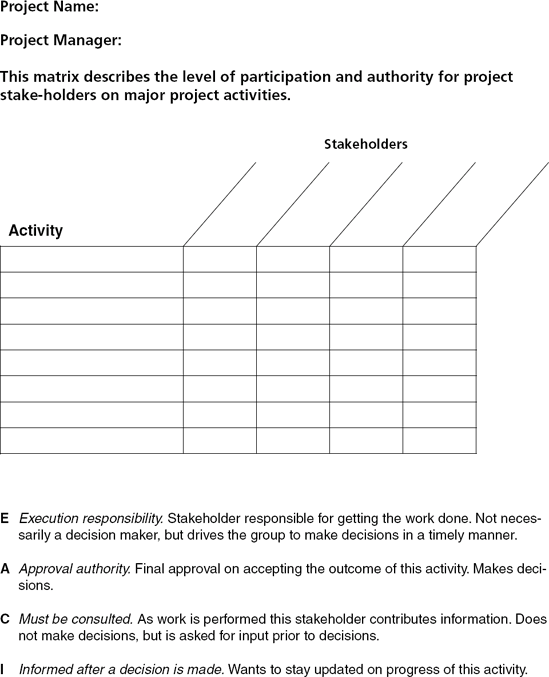

There is, however, a need for another document that precisely details the responsibilities of each group involved in a project. It is known variously as a responsibility assignment matrix (RAM), RACI chart, or simply responsibility matrix. The importance of this document is growing as corporations reengineer themselves and form partnerships and virtual companies. In these kinds of environments, many groups that otherwise might have nothing to do with each other are brought together to work on projects.

A responsibility matrix is ideal for showing cross-organizational interaction. For example, when a truck manufacturer creates a new cab style, it requires changes in tooling for the supplier as well as on the assembly line. The inevitable questions then arise: Who will make design decisions? Will the supplier have a voice in these decisions? When does each group need to get involved? Who is responsible for each part of the project? The responsibility matrix is designed to answer questions like these.

Setting Up a Responsibility Matrix

A responsibility matrix lays out the major activities in the project and the key stakeholder groups. Using this matrix can help avoid communication breakdowns between departments and organizations because everyone involved can see clearly who to contact for each activity. Let's look at the steps involved in setting up a responsibility matrix:

List the major activities of the project. As shown in Table 4.2, only the major project activities are listed on the vertical axis; detailed task assignments will be made in the project plan. (Table 4.2 is a sample responsibility matrix for the training project described in Table 4.1.) Because the responsibility matrix shows interaction between organizations, it needs to emphasize the different roles required for each task. In highlighting the roles of the various stakeholders involved in the project's major activities, the matrix in Table 4.2 uses the same level of detail as the scope statement in Table 4.1.

On very large projects it can be useful to develop multiple responsibility matrixes with differing levels of detail. These matrixes will define subprojects within the larger project.

List the stakeholder groups. Stakeholder groups are listed on the horizontal axis of the matrix. Notice how groups such as project team and user council are named rather than individual team members; these individual team assignments are documented in the project plan. It is appropriate, however, to put individual names on the matrix whenever a single person will be making decisions or has complete responsibility for a significant part of the project.

Table 4.2. RESPONSIBILITY MATRIX FOR PROJECT MANAGEMENT TRAINING ROLLOUT

Activity

Training Team Project Manager

Project Office

VP Operations (Sponsor)

Site Coordinators

HR Director

Legend: R = responsible for execution; A = final approval authority; C = must be consulted; I = must be informed.

The training team and project manager report to the director of human resources.

The project office is not managing the project; they are the subject matter experts.

Notice how this responsibility matrix defines major tasks in much the same way as the scope statement in Table 4.1.

The task level emphasizes the interaction among these stakeholders during the project.

Develop training objectives

R

C/A

A

A

A

Outfit training rooms

R

A

R

Acquire the rights to use/modify training materials

R

C

A

C

Modify training materials

R

I

Establish materials production process

R

A

C

Recruit qualified trainers

I

C/A

A

R

Train and certify instructors

R

I

Promote training to divisions

R

R

R

R

R

Schedule classes, instructors

R

I

I

R

Administer travel

R

I

I

Standardize project management practices

I

R

A

I

Identify training participants

R

R

Administer site training logistics

I

R

Code the responsibility matrix. The codes indicate the involvement level, authority role, and responsibility of each stakeholder. While there are no limits to the codes that can be used, here are the most common ones:

R—Responsible for execution. This person or group will get the work done.

A—Approval authority (usually an individual). This person has the final word on decisions or on acceptance of the work performed (i.e., has final accountability for this activity).

C—Must be consulted. This group must be consulted as the activity is performed. The group's opinion counts, but it doesn't rule.

I—Must be informed. This group just wants to know what decisions are being made.

Notice how decisions can be controlled using A, C, and I. Specifying clearly these different levels of authority is especially useful when there are different stakeholders who all want to provide requirements to the project. For example, in Table 4.2, the project office has a say in selecting the basic course materials and instructors, but is left out of modifying the training or certifying the instructors. By using the responsibility matrix to specify these responsibilities, the project manager (in the training department) has successfully managed the role of the project office.

Incorporate the responsibility matrix into the project rules. The matrix becomes part of the project rules, which means that once it is accepted, all changes must be approved by those who approved the original version. The advantage to this formal change management process is that the project manager is always left with a written document to refer to in the event of a dispute. There is a downloadable form for creating a responsibility matrix at the end of this chapter.

Tip

Clarify Authority

When writing out the responsibility matrix you need to leave no doubt about who must be consulted and which stakeholder has final authority. This will have the effect of bringing out any disagreements early in the project. It's important to make all these distinctions about authority and responsibilities early, when people are still calm. It's much more difficult to develop a responsibility matrix during the heat of battle, because people have already been acting on their assumptions and won't want to back down. Disagreements on these issues later in the project can escalate into contentious, schedule-eating conflicts.

People make projects happen. They solve problems, make decisions, lay bricks, draw models, and so on. It is the job of the project manager to make other people more productive. Through agreements, plans, recommendations, status reports, and other means, a project manager coordinates and influences all the stakeholders while giving them the information they need to be more productive. He or she also manages customer expectations. But no matter what the task, every action of a project manager includes communication. Careful planning reduces the risk of a communication breakdown.

Let's look at what can happen when such a breakdown occurs. Dirk, a project manager for a consulting firm, tells this story:

We were assisting one of the biggest pharmaceutical companies in the United States with FDA approval for a new production facility they were building. Like most of our projects, the client requested a lot of changes as we proceeded. I followed the normal change management process outlined in our contract, getting the client project manager to sign off on any changes that would cause a cost or schedule variance with the original bid. Although the changes caused a 50 percent increase over the original budget, the client approved each one, and I thought I was doing my job right.

When we finished the project and sent the bill for the changes, our customer's president saw it and went ballistic. He came down to my office and chewed me out. He'd never heard of any changes to the original bid, and he sure didn't expect a 50 percent cost overrun. The president of my company flew out to meet with the customer's president. I spent two weeks putting together all the documentation to support our billing, including the signed change orders. We did get paid, but you can bet I didn't get an apology from their president. And we didn't bill them for the two weeks I spent justifying the bill.

I made the mistake of assuming the client's project manager was passing on the cost overrun information to his superiors. I don't make that mistake any more.

This story illustrates the dangers of letting communication take care of itself. The answers to questions like, "Who needs information?" "What information do they need?" "When and how will they get it?" vary on every project.

A communication plan is the written strategy for getting the right information to the right people at the right time. The stakeholders identified on the statement of work, the organization chart, and the responsibility matrix are the audience for most project communication. But on every project, stakeholders participate in different ways, so each has different requirements for information. Following are the key questions you need to ask, with tips for avoiding common pitfalls:

Who needs information?

- Sponsor.

The sponsor is supposed to be actively involved in the project. There shouldn't be a question about who the sponsor is after writing the statement of work.

- Functional management.

Many people may represent functional management. Their two basic responsibilities of providing resources and representing policy will dictate the information they need. Each functional manager's name or title must appear on the communication plan, though it may be appropriate to list several together as having the same information needs.

- Customers.

Customers make decisions about the business case—what the product should be, when it is required, and how much it can cost. There are likely to be many different levels of customer involvement, so individual names or titles must be listed.

- Project team.

The project team can be a particularly complex communication audience. It will be relatively straightforward to communicate with the core team, because they'll be tightly involved in the project. Other project team members, such as vendors, subcontractors, and staff in other departments, may have a variety of communication barriers to overcome, so each will need to be evaluated separately.

- Project manager.

While the project manager is the source of much information, he or she will often be on the receiving end as well.

What information is needed? In addition to the obvious cost and schedule status reports, several other types of information are distributed during the project. Basically, three categories classify how information is managed:

- Authorizations.

Project plans, the statement of work, budgets, and product specifications must all be authorized. Any document that represents an agreement must have an approval process, including steps for reviewing and modifying the proposal. Be specific about who will make the decision.

- Status changes.

Reports with cost and schedule progress fall into this category. So do problem logs. It is common to issue status reports, but the content of each report should be specific to the audience receiving it.

- Coordination.

The project plan helps to coordinate all the players on a project. It contains the tasks and responsibilities, defines the relationships between groups, and specifies other details necessary to work efficiently. When change occurs during the course of a project, coordination among teams or locations is often required on a daily basis. The communication plan should record the process for keeping everyone up-to-date on the next steps.

Warning

Keep the Status Report Short

A common mistake is to include in the status report everything about the project that anyone might want to know. Instead of having the intended effect of informing everyone, these obese reports are overwhelming for a busy audience. When developing the report content, keep it practical. A department manager responsible for 250 projects made the point this way, "Some of our project leaders have 10 projects. If they have to spend two hours a week writing status updates, there won't be any time left for them to do work. They report to supervisors overseeing up to 80 projects. We need a way to identify and communicate the key information quickly so project leaders and supervisors can spend time solving problems and moving the projects ahead!"

Tip

Set Up an Escalation Procedure

Some problems get out of hand because they must be passed up several layers of authority before they can be resolved. The project manager must set up a procedure for communicating with higher management—called an escalation procedure—when a project begins to run over cost or schedule. This escalation procedure will determine which level of management to contact, depending on the degree of variance from the plan. (See Chapter 12 for further discussion of escalation thresholds.)

Make Information Timely

For information to be useful, it has to be timely. As part of the communication plan, the project manager needs to decide how often to contact each stakeholder and with what information. In fact, stakeholder response to the communication plan is a way of discerning the involvement level of each stakeholder. For example, a sponsor who won't sign up for frequent status meetings or reports is signaling his or her intention to support this project from afar. Table 4.3 uses a matrix to map which information needs to be communicated to each stakeholder and how often. Notice that a time for response is designated in Table 4.3; unless the stakeholder agrees to respond within this required time, his or her commitment to the project remains in question. The downloadable form for building this type of communication plan is included at the end of this chapter.

Table 4.3. COMMUNICATION PLAN

Stakeholder | What Information Do They Need? | Frequency | Medium | Response |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Even a simple plan makes communication more deliberate and represents stakeholder commitment to attending meetings and responding in a timely manner. | ||||

Sponsor |

| Monthly | Written report and meeting | Required in 3 days |

PM's supervising management |

| Weekly | Written report and meeting | |

Customer executive |

| Monthly | Meeting with project sponsor Published meeting minutes | Required in 5 days |

Customer contact |

| Weekly | Written report and meeting Include in project team meeting | Required in 3 days |

Project team |

| Weekly | Project team meeting Published meeting minutes | |

Tip

Include Regular Meetings in the Communication Plan

It's best to have regularly scheduled progress meetings written into the communication plan. While everyone says they would rather be proactive than reactive, many sponsors or supporting managers want to have status meetings only as needed—meaning only when there is a big problem. They are willing to let the project manager handle everything as long as it is going smoothly (they call this type of uninvolvement "empowering the project manager"). In reality, when troubles occur, by the time these higher-level managers get involved, it is often too late for them to help. This is why scheduled meetings are important. If things are going smoothly, the meetings won't take long, but if a problem does arise, these meetings will give management the background information they need to be effective.

How Will Communication Take Place?

There are now myriad ways to stay in constant communication. Internet and intranet technologies allow more people to share information simultaneously. Status reports are now posted on project web sites, and videoconferencing enables project teams to be spread around the world and still meet face to face. But with all these options, the question still remains the same: What is the best way to get the information delivered? One thing is certain: Technology doesn't have all the answers. Putting a project's status on a web site, for instance, doesn't ensure that the right people will see it. You need to consider the audience and its specific communication needs. For example, because high-level executives are usually very busy, trying to meet with them weekly—or sending them a lengthy report—may not be realistic.

Consider the communication breakdown described earlier in this chapter. After Dirk's client contact failed to report budget overruns, he learned the hard way how to manage communication with a customer: "After that project, I always plan for my president to meet with a client executive at least quarterly. It goes into our contract. The client likes to see our president on-site, too, because it shows we take them seriously." In this case, the medium isn't just a meeting—it is a meeting with the president. (This is also an example of the company president being a good sponsor for the project manager.)

Dirk has learned to get his customers to commit to regular project status meetings. He includes this commitment in the contract, and, because the commitment is clear and formal, the customer is likely to pay attention to it.

Not all projects, however, need that level of formality. In the case of small projects with few stakeholders, you might find that discussing communication expectations early in the project is sufficient. A project manager might build a communication plan solely for his or her own benefit and use it as a strategy and a self-assessment checklist during the project without ever publishing it. In either case, whether a communication plan is formally accepted as part of the project rules or is just a guide for the project manager, the important thing is that communication has been thoughtfully planned, not left to chance.

Tip

Take a Tip from Madison Avenue

If you want to communicate effectively, why not take a lesson from the folks on Madison Avenue? Whether they are running ad campaigns for cars or computers, movies, milk, or sunscreen, they use both repetition and multiple media channels. You can mimic this by providing hard-copy reports at status meetings and then following up with minutes of the meeting. In the case of a video- or teleconference, providing hard-copy supporting materials becomes even more important.

Don't Miss Out on Informal Communication

While it is important to plan for communication, it is also true that some of the best communication takes place informally and unexpectedly. You can nurture the opportunities for informal communication. Be available. Get into the places where the work is being done or the team members are eating their lunch. Listen. Watch for the nonverbal, unofficial signs of excitement, confusion, accomplishment, or burnout.

Project managers deliver projects, but do they deliver the right projects? If it is on time, within budget, and has the specified quality, how could it be anything but a success? The activities described previously in this chapter build a strong foundation for successful project execution—whether the project is worthwhile or not! As a project manager, you may not be responsible for deciding which projects to pursue, but you might participate in developing a project proposal, the basis for project selection.

Should we launch a new product? Invest in a new wing at the R&D facility? Implement the latest supply chain management software? These potential projects could provide big payoffs or produce huge disappointment. The sophisticated analysis necessary to make these decisions is beyond the scope of this book, but we can understand the fundamental factors that contribute to any business case and thereby improve our ability to manage the project to achieve the maximum benefit.

The Foundation of the Statement of Work

The basic content of the project proposal overlaps the content found in the statement of work. That makes sense, because both are used to move a project from an inspiration to a tangible, achievable goal. Since the proposal is written first, any overlap with the statement of work represents an opportunity to either verify an earlier assumption or to develop that topic in greater detail.

A Mini-Analysis Phase

As we'll see next, the content of the project proposal covers many topics that will be investigated in greater detail further along in the project. For example, articulating business requirements and predicting the tangible benefits are often performed in detail once a project is approved. It helps to understand the time spent developing the business case as a mini-analysis phase—knowing we won't take the time to thoroughly investigate every option and check up on every assumption, but instead will assemble enough information to make the decision to formally launch the project. We know that we will continue to evaluate the worth of the project as it progresses through subsequent phases. This iterative approach to project selection is consistent with phased estimating, which is presented in Chapter 8.

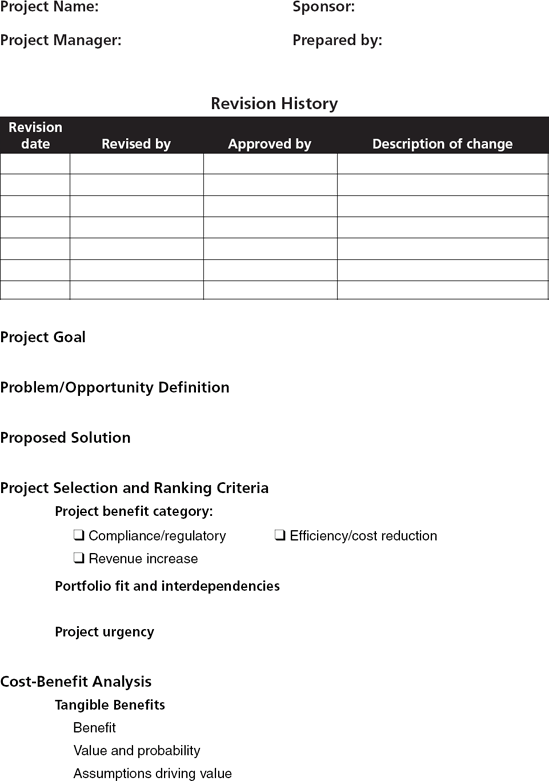

Basic Project Proposal Content

The information and analysis required to select a project will vary dramatically depending on your industry and the size of your projects. The content described here addresses the minimum topics most project selection boards require. You may find it useful to reference the downloadable forms at the end of this chapter as we explore each section of the proposal. The overall project selection and portfolio management process is described in Chapter 15.

1. Project Goal

State the specific desired results from the project over a specified time period. For example, the goal of a training project could be: "This project will improve our ability to plan projects with accuracy and manage them to meet cost, schedule, and quality goals."

2. Problem/Opportunity Definition

Describe the problem/opportunity without suggesting a solution. The people approving the project must understand the fundamental reason the project is being undertaken. This problem/opportunity statement should address these elements:

Describe the problem/opportunity. If possible, supply factual evidence of the problem, taking care to avoid assumptions.

Describe the problem/opportunity in the context of where it appears in the organization and what operations or functions it affects.

List one or more ways to measure the size of the problem. Qualitative as well as quantitative measures can be applied.

3. Proposed Solution

Describe what the project will do to address the problem/opportunity. Be as specific as possible about the boundaries of the solution such as what organizations, business processes, information systems, and so on will be affected. If necessary, also describe the boundaries in terms of related problems, systems, or operations that are beyond the scope of this initiative.

4. Project Selection and Ranking Criteria

Ideally, your firm has specific selection or ranking criteria that is addressed here. The example categories here might assist a selection board in ranking one project against another.

- Project benefit category.

Projects typically fall into one of the following categories:

Compliance/regulatory. Laws or regulations dictate the requirements for the project.

Efficiency/cost reduction. The result of the project will be lower operating costs.

Increased revenue. For example, increased market share, increased customer loyalty, or a new product could all produce increased revenue.

- Portfolio fit and interdependencies.

How does this project align with other projects the organization is pursuing and with the overall organization strategy?

- Project urgency.

How quickly must the organization attempt this project? Why?

5. Cost-Benefit Analysis

This section summarizes the financial reasons for taking on the project. It consists of an analysis of the expected benefits in comparison to the costs with an attempt to quantify the return on investment.

- Tangible benefits.

Tangible benefits are measureable and will correspond to the problem/opportunity described in item 2. For each benefit, describe it and quantify it, including a translation of the benefit into financial terms such as dollars saved or gained. Include any assumptions you used in calculating this benefit. Forecast benefits are usually not certain, so describe the probability of achieving the result.

- Intangible benefits.

Intangible benefits are difficult to measure, but are still important. For example, reducing complexity in a task may increase employee job satisfaction, a worthwhile benefit but a difficult one to measure. Again, describe the benefit, the assumptions used to predict the magnitude of this benefit, and the probability the benefit will be realized.

- Required resources (cost).

What labor and other resources will be required? Include a comment about the accuracy of these figures. Typical cost categories include internal (employee) labor hours, external labor, capital investment, and the ongoing cost to support the result of the project.

- Financial return.

There are many financial methods that compare the tangible up-front cost of the project with the expected tangible benefits achieved over time. These are beyond the scope of this book, but your project selection committee should describe which of these financial measures to use.

6. Business Requirements

Describe the primary success criteria for the project in terms of what the business or customer will be able to do as a result of the project's successful completion. Many completed projects are a disappointment to the customer because they don't really address the core business/functional need that the customer had. It takes skill to uncover and document business requirements, because they usually lurk beneath the surface—below the symptoms of the problem or the customer's perception of what solution should be implemented. Remember that these requirements will be elaborated on during subsequent phases of the project, so the goal in the proposal is to understand the primary results to be achieved at a high level.

Tip

Requirements Record the Customer's View

If you describe a requirement using one of the following phrases, you are more likely to be accurately describing the true end state desired by the customer.

The project will be judged successful when . . .

We know ______________________________________________________

We have _______________________________________________________

We can ________________________________________________________

We are ________________________________________________________

You can substitute the names of specific users or customers in these statements, such as "Project sponsors know the cost and schedule status of all projects for which they have responsibility."

7. Scope

List and describe the major accomplishments required to meet the project goal. These may include process or policy changes, training, information system upgrades, facility changes, and so forth. Clearly an overlap to the statement of work, the scope description in the proposal is likely to be less detailed than the one developed for that document.

8. Obstacles and Risks

Describe the primary obstacles to success and the known risks (threats) that could cause disruption or failure. The difference between obstacles and risks is that risks might occur, but obstacles are certain to occur. Chapter 5 describes how the risk management process works continuously throughout the project to help identify potential threats and either avoid them or reduce their negative impact.

9. Schedule Overview

At a high level, describe the expected duration of the project (planned start and finish), significant milestones, and the major phases. This is an initial schedule estimate that will be refined during project definition and planning, but it is always useful to manage expectations by commenting on the accuracy of this schedule prediction.

Increase Your Value

For the purposes of this book, it is assumed that project managers are typically assigned to projects that have already been selected. In that case, the project manager uses the project proposal as the starting point for writing the project rules and creating a detailed plan. However, a proposal is far more than a starting point: It is the reason the project exists. Understanding every aspect of a project proposal makes a project manager much more valuable to the project's owner, because that means the project manager will make all decisions in the context of the ultimate goals for the project. Further, project managers looking for greater responsibility in the firm should realize that projects achieve goals—and that those who can select the right goals for a firm ultimately make a far larger impact than those who simply carry out orders.

Each project is a new beginning, with new opportunities and new pitfalls. Making the project rules will put it on a firm footing and point it toward three of the five project success factors.

The project team, customer, and management must all agree on the goals of the project. Write down the goals and constraints in the statement of work and let the stakeholders demonstrate their agreement by signing it.

The size (scope) of the project must be controlled. Listing the deliverables and writing the scope statement are the first steps for controlling scope. Once the statement of work is signed, it can be used as a tool to refocus all the stakeholders on the legitimate responsibilities of the project.

Management support. Tangible support from management starts with issuing the project charter and signing the statement of work.

The project definition activities in Chapters 3 and 4 are the foundation of project management. The activities in the next two stages—planning and control—rely on the agreements made in the project rules. The project plan will depend heavily on the responsibilities, scope, and deliverables defined during this stage. Communication strategies will form a structure for project control.

Making the project rules is also the first opportunity for the project manager to exercise leadership. Successfully bringing the stakeholders to an agreement about the fundamental direction of the project will establish your role as the leader.

Start the project with a strong foundation. The templates and checklist you find on the next several pages address the key actions required to initiate the project with clear goals, effective communication, and management support.

The project proposal assembles the information necessary for a sponsor or project selection board.

A project sponsor can use the charter template to formally authorize the project and project manager.

The statement of work represents the formal agreement between project stakeholders about the goals and constraints of the project.

The responsibility matrix clarifies the role and authority of each project stakeholder.

Effective communication is no accident. Use the communication planning matrix to identify who needs what information and how you'll be sure to get it to them. Remember that having more mediums of communication increases the likelihood your message will get through.

As you initiate the project, use the definition checklist to guide the team.

Every one of these templates is available for download at www.versatilecompany.com/FFMBAinPM. Use these documents as the foundation of your own project management standards.

Downloadable Project Proposal[6]

Downloadable Project Proposal[7]

Downloadable Project Charter[8]

Downloadable Statement of Work[9]

Downloadable Responsibility Matrix[10]

Downloadable Communication Plan[11]

Downloadable Definition Checklist[12]

Project Name:

Project Manager:

Stakeholder Analysis

The project sponsor is known and actively involved in supporting the project.

The project sponsor has sufficient authority within the project environment to effectively champion the project team.

Functional managers supplying personnel or other resources to the project have been identified and are ready to supply the required resources.

The people who will approve requirements and specifications, changes to requirements and specifications, and who will accept the final product are identified and have agreed to the process for these approvals.

The people who will approve funding and changes to funding are known and a process exists for approving changes to funding.

Stakeholders inside and outside the firm that will have veto power over any decision in the project are known and are identified in the responsibility matrix and communication plan.

All contributors necessary to complete the project have been identified and understand their role on the project.

The stakeholders that will receive and operate the outcome of the project are included in the responsibility matrix.

Stakeholders who will be affected by the outcomes of the project are known, their stake is understood, and there is a strategy for managing them to benefit the project.

A project charter that clearly identifies and shows management support for the project manager has been published.

Project Proposal

A project proposal has been prepared and approved.

The project manager has received and understands the proposal.

Any future milestones requiring an updated proposal and renewed approval have been identified.

Documenting the Rules

A statement of work has been accepted in writing by the primary stakeholders.

The assumptions used to write the statement of work, particularly the cost and schedule estimates, are identified as assumptions and are realistic.

There is a clear chain of authority for escalating issues and making timely decisions.

A communication plan exists to identify the strategies for keeping all project stakeholders appropriately informed.

A responsibility matrix has documented the roles of the various stakeholders as they relate to the major decisions and activities within the project. The stakeholders represented on the responsibility matrix have agreed that it accurately represents their involvement.

A process has been established for evaluating and approving changes to the statement of work, specifications, requirements, and other control documents.

Answers to these questions are found at www.versatilecompany.com/FFMBAinPM.

[5] Project Management Institute, A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge Third Edition (Newtown Square, PA: PMI, 2004), p. 45.

[6] Copyright Eric Verzuh 2008. Original purchasers of this book are permitted to photocopy or customize this page by downloading it from www.versatilecompany.com/FFMBAinPM. The document can then be opened, edited, and printed using Microsoft Word or other word processing software.

[7] Copyright Eric Verzuh 2008. Original purchasers of this book are permitted to photocopy or customize this page by downloading it from www.versatilecompany.com/FFMBAinPM. The document can then be opened, edited, and printed using Microsoft Word or other word processing software.

[8] Copyright Eric Verzuh 2008. Original purchasers of this book are permitted to photocopy or customize this page by downloading it from www.versatilecompany.com/FFMBAinPM. The document can then be opened, edited, and printed using Microsoft Word or other word processing software.

[9] Copyright Eric Verzuh 2008. Original purchasers of this book are permitted to photocopy or customize this page by downloading it from www.versatilecompany.com/FFMBAinPM. The document can then be opened, edited, and printed using Microsoft Word or other word processing software.

[10] Copyright Eric Verzuh 2008. Original purchasers of this book are permitted to photocopy or customize this page by downloading it from www.versatilecompany.com/FFMBAinPM. The document can then be opened, edited, and printed using Microsoft Word or other word processing software.

[11] Copyright Eric Verzuh 2008. Original purchasers of this book are permitted to photocopy or customize this page by downloading it from www.versatilecompany.com/FFMBAinPM. The document can then be opened, edited, and printed using Microsoft Word or other word processing software.

[12] Copyright Eric Verzuh 2008. Original purchasers of this book are permitted to photocopy or customize this page by downloading it from www.versatilecompany.com/FFMBAinPM. The document can then be opened, edited, and printed using Microsoft Word or other word processing software.