"When the satellite TV truck has pulled into the corporate parking lot, it is too late to discuss crisis management."

Picking up the phone and discovering there's a journalist on the other end of the line can cause your heart to skip a beat, making it potentially easy to say something inappropriate and newsworthy. It's a natural reaction. Unless you've just won a Nobel Prize or an Academy Award, rarely does a journalist call because it's good news. I've personally witnessed the darting eyes, sweat-soaked shirt, and trembling voice of a newsmaker or spokesperson caught off-guard by an unexpected inquiry. But how you manage this initial encounter may very well determine whether the ensuing media interaction will be a success or a failure. It will be your first chance to dispel rumors or address controversy. It will be an opportunity to begin shaping the resulting news story and influencing public perception. In this chapter, you will learn how to manage the initial encounter with a journalist, avoid common interview traps, and align your organizational image with positive values.

Unless you proactively seek media coverage, most interview encounters begin with a phone call from a reporter. From the instant you answer the phone to the instant you get off the phone, everything you say could be on the front page of tomorrow's paper. Therefore, the initial phone call or confrontation requires a basic strategy for managing surprise inquiries, as well as a clear understanding of the rules that govern media interaction with the public. When a journalist calls or confronts you in your company's lobby, follow this simple three-step strategy:

When a reporter asks for an interview, the reporter can sense whether you want to talk or not. If the reporter hears stress, irritation, or anxiety in your voice, it could be an immediate tip-off that you may be less than cooperative and may, in fact, have something to hide. When you're involved in a controversial incident, the reporter invariably expects you to be defensive upon contact. The conversation that follows is almost certain to move in a negative direction based simply on the tense, impatient tone of your voice. To reduce this possibility, try to sound as friendly as possible. By sounding friendly, you will convey a desire to be helpful and forthcoming. In many cases, when a reporter is looking for a villain or "village idiot" to anchor a story, she may be thrown off by a friendly and cooperative demeanor. When I was a reporter, if someone I was hoping to vilify responded in a warm and friendly manner, I immediately considered trying to find someone else to interview.

It's natural to be nervous when speaking with a journalist, but that doesn't mean you need to sound nervous. To sound friendly, use a conversational vocal inflection. This means trying to talk as you do when you are engaged in a relaxed, enjoyable conversation. One very effective way to make your voice sound more conversational is to use your hands when you talk. In Chapter Five, I provide a number of other techniques to help you seem relaxed in stressful situations, so be sure to review those as you practice sounding genial and forthcoming. Once you have presented a friendly, relaxed persona to the reporter, move on to Step Two.

Though the reporter wants you to drop everything and be interviewed right now, you are entitled to a couple of moments to gather your thoughts. Tell the reporter, "I'm just in the middle of something right now"—which you no doubt are, even if it's playing solitaire. Then add, "Please tell me how I can be of service and I will do my best to help." You should never do an interview with the media or provide a reporter with meaningful quotes until you know the proposed content and context of the story.

If the reporter hesitates to provide appropriate information on the story, be very careful. A reporter may not tell you the true or entire purpose of the intended story if he thinks full disclosure would kill the opportunity for an interview. For example, while investigating nursing homes during my reporting days, I told the administrator of one home that the purpose of my interview was to shed light on what life was like for seniors in these facilities. In actual fact, my purpose was to get the administrator's reaction to allegations of resident abuse. If I had told her that, however, I never would have been invited into the home. To be true to my word, the first ten minutes of the interview were dedicated to general questions about life in a nursing home. Then, when the administrator's guard was down, I hit her with questions about residents suffering abuse and malnutrition.

More often than not, though, a reporter will tell you the true purpose of the call. Generally, reporters avoid lying in order to get a story. They know they'll have to answer for it later, either to their editor or a judge. But there is a lot of wiggle room between "tell the truth" and "don't lie." If you are unprepared to be questioned or do not have a complete understanding of what the journalist is looking for, be sure not to answer questions that could be problematic. Instead, move on to Step Three.

Although reporters make their living asking questions, it often benefits you to reverse roles and ask a series of questions of your own. The answers you get to these initial questions will provide insight into the content and context of the proposed interview and the resulting news story. If you sense the reporter is hesitant to answer your questions, it may be because the reporter is holding back and wants to surprise you with a question or issue you aren't expecting. In that initial call or contact, ask the following questions to determine the needs of the journalist and pay careful attention to what she tells you—or doesn't tell you.

When talking to a print or newspaper reporter, ask:

What's the purpose of the interview? (Let the reporter explain why she contacted you.)

When will the article be published? (Provides you with a sense of timing.)

What's the article's overall objective? (Meant to give you insight into the end result the reporter is looking for and ensure the objective is in keeping with the purpose of the interview.)

Who else are you interviewing? (Know who else will be quoted. If the reporter refuses to answer, you should hear alarm bells.)

What section of the paper is the article for? (Know the audience—is it for the news section, the business section, or the style section?)

Are you interested in reporting on ____? (Fill in the blank with a topic that benefits you. It's possible you can help shape the story by providing information the journalist was, up to now, unaware of.)

How much time do you need for the interview and where do you want to do it? (If the reporter says she needs thirty to sixty minutes, then your information will play a prominent role in the story. Doing the interview on your own turf provides an opportunity to influence the setting and tone.)

What's your deadline? (I always told people my deadline was sooner than it actually was to pressure them into responding faster.)

What's your phone number and e-mail address so I can get back to you? (When you are the one to initiate the response or callback, it is easier to influence the flow of conversation and end it at the appropriate time.)

While most of the questions for TV or radio reporters are the same, there are a few critical differences between the broadcast and print mediums. Generally speaking, TV is more intimate and revealing. Seeing a person run away from a TV camera has greater impact than reading about it. If you refuse to talk to a TV reporter, all she has to do is barge into your office or show up on your front step to get visuals of you refusing to talk, covering your face, or trying to push away the camera. All of these images make for compelling TV. Likewise, there is a greater immediacy to TV news. CNN, FOX News, and other all-news outlets are starved for content. As such, they are in constant search of images. And with the popularity of YouTube, any gaffe that is captured on camera lives on the Web in perpetuity. So in a sense, more is at risk when you either participate in or refuse to do a television interview. With that in mind, following is a list of questions to ask a broadcast journalist.

When talking to a TV or radio reporter, ask:

What's the purpose of the interview? (Let the reporter explain why she contacted you.)

When will the story be broadcast? (Provides you with a sense of timing.)

What's the segment's overall objective? (Meant to give you insight into the end result the reporter is looking for and ensure the objective is in keeping with the purpose of the interview.)

Who else are you interviewing? (Know who else will be contacted. If the reporter refuses to answer, you should hear alarm bells.)

Will the interview be "live" or "taped"? (Taped interviews can be edited to fit the reporter's perspective.)

Is the interview for a ninety-second news report or is it for a longer feature? (For shorter segments, you need more focused and quotable messages.)

Are you interested in reporting on ____? (Fill in the blank with a topic that benefits you. It's possible you can begin shaping the story by providing information the journalist was, up to now, unaware of.)

How much time do you need for the interview and where do you want to do it? (Lengthy interviews offer more opportunities for mistakes. Doing the interview on your own turf provides an opportunity to influence the setting and tone.)

What's your deadline? (I always told people my deadline was sooner than it actually was to pressure them into responding faster.)

What's your phone number and e-mail address so I can get back to you? (When you are the one to initiate the response or callback, it is easier to influence the flow of conversation and end it at the appropriate time.)

When you ask reporters to tell you about their story, frame each question from the perspective of wanting to help. If you simply say, "What's the purpose of the interview?" the reporter can write, "'What's the purpose of the interview,' barked an irritated Ansell." Better to say, "I want to appreciate the scope of the story—please help me understand the purpose of the interview." Or, "To help me understand the breadth of the story, please share with me who else you'll be interviewing." That way, your questions will not sound like an interrogation.

If the reporter will not let you off the phone in that initial call and persistently fires questions at you, tell her, "The sooner I wrap up what I'm doing, the sooner I can get back to you with all the information you need." Then, once you have the information needed to answer her questions and highlight your own agenda, get back to the reporter at a designated time. If the designated time passes, call or e-mail the reporter with an update.

When you do call back, "winging it" is not advisable—even if you consider yourself a skilled public speaker. Giving presentations and answering questions from the media are two very different situations. Questions and comments cannot always be predicted, and as helpful as the gift of gab may be it is not nearly enough to succeed during a media interaction. The gift of gab can actually work against you, especially if you aren't extremely careful with what you say or don't completely understand the meaning of journalistic terms like "off the record."

When a reporter is on the phone, every word is fair game for a quote. This means you can count on the reporter combing through what you say very carefully for something, anything, to get his story printed. For example, consider the following fictional telephone exchange:

- Reporter:

I'm working on a story about rumored layoffs at your plants.

- Spokesperson:

So you want to talk about rumors of layoffs.

- Reporter:

I also want to talk about the rumor that you've lost the government funding you were hoping for.

- Spokesperson:

So you also want to talk about a rumor that we have lost our funding.

- Reporter:

I would also like you to comment on the possibility your CEO and CFO may be fired by the board of directors.

- Spokesperson:

And you want to talk about the board possibly firing the CEO and CFO.

In this brief exchange, look at the words the spokesperson used by merely repeating what the reporter asked:

". . . rumors of layoffs"

". . . we have lost our funding"

". . . possibly firing the CEO and CFO"

The reporter now has numerous options for piecing together a dramatic headline to splash across the front page of tomorrow's business section. Here is a better way for a spokesperson to handle this conversation:

- Reporter:

I'm working on a story about rumored layoffs at your plants.

- Spokesperson:

So you want to talk about our workforce.

- Reporter:

I also want to talk about the rumor that you've lost the government funding you were hoping for.

- Spokesperson:

So you also want to talk about funding.

- Reporter:

I would also like you to comment on the possibility your CEO and CFO may be fired by the board of directors.

- Spokesperson:

And you want to talk about our executive team.

In this exchange, the spokesperson has acknowledged the reporter's questions in a responsive and accommodating way, but without providing the reporter with quotable information. Remember, everything you say in that opening conversation can be reported by the journalist. Therefore, always be very careful.

"Off the record" is a journalism term that means a statement is not for publication or attribution. Although there is controversy surrounding the origins of the term, it certainly has been popularized in movies and TV dramas. These fictional depictions have led people to believe that journalists follow a strict set of rules when it comes to sourcing material and dealing with the public. The fact is there are no definitive rules and nothing is ever truly "off the record." Many people have been burned thinking otherwise. If you're not certain whether to share specific information with journalists, follow this simple credo—when in doubt, leave it out.

If you're determined to ignore the above advice, only agree to go off the record with a reporter you absolutely trust to keep your remarks off tonight's newscast or out of tomorrow's newspaper. But unless you're really certain, that's a big chance to take. If you do tell a reporter that your comments are off the record, at least do so before you offer the comments. Off the record is not retroactive. The following is a great example of a savvy and successful businessman who believed the "off-the-record" myth.

Drug company owner Barry Sherman was interviewed by Leslie Stahl of 60 Minutes. Stahl's story was about a medical researcher who claimed to be a victim of a smear campaign by Sherman's company. Here's a partial transcript of Stahl's report:

- Sherman:

She (the researcher) is the one who is conducting the smear campaign.

- Leslie Stahl (voiceover):

But when we changed the tapes, he changed his tune, unaware that the cameras were rolling again.

- Stahl:

Let me finish this and then we'll go back. . . .

- Sherman:

She's nuts. Nuts.

- Stahl:

What did you just say to me? You just said she was nuts. You just said that to me. You looked at me and you said she was nuts.

- Sherman:

I said to you. . . .

- Stahl:

- Sherman:

Hold on a sec. I said I'll say certain things to you off the record. . . .

- Stahl:

Yes, but that wasn't off the record. We were rolling. The cameras were going. The point is that you are still saying these things and I am a reporter.

- Sherman:

I am obviously very upset and given that I'm upset I might well say things that in a private conversation, off the record, that I would not say on. . . .

- Stahl:

Yes, but we're reporters. We're not your pals.

Commenting on Sherman's encounter with Stahl, journalist John Fraser was less than kind to his colleagues: "Journalists can be good and decent people just like any other professionals. They can also be perfect shits."[20]

Corporate image involves how consumers perceive the corporate entity behind the brands it markets or the services it provides. A positive image helps sell product. It boosts share price and influences public trust. A positive corporate image greatly increases brand equity and brand adoption. In short, image matters to a company's bottom line. So much so that, according to a comprehensive eMarketer report compiled by David Hallerman, corporations and organizations in the United States spend in excess of $250 billion per year on advertising to help shape their image.[21] But a corporation's image is not solely created by the company. Other contributors to a company's image include consumers, journalists, bloggers, and advocacy groups. Therefore, when a reporter calls or a crisis occurs, it's important to know what others are saying about your organization and to be aware of how you come across in the court of public opinion.

To help manage your organization's reputation, you should troll the Web to identify what, if anything, is being said about you and who is saying it. Although monitoring the myriad sites that could be talking about you is a monumental task, google.com is a good place to start. Free blog search tools can help, too. They include blogsearch.google.com; technorati.com, which searches for user-generated media (including blogs) by tag or keyword; and blogpulse.com, which analyzes and reports on daily activity in the blogosphere. Other sites helpful to search beyond blogs include search.twitter.com and uservoice.com.

In all searches, look for keywords connected to your business or the names of your products and add words like "sucks," "blows," and "stinks." You may not like what you find. Brian Solis of Future Works discovered two-thousand-plus Web domains that ended with the phrase ". . . stinks.com." Some organizations beat critics to the punch and actually purchase domains with their company name followed by the words "sucks" or "stinks."

Many successful companies see the value in actively following and managing their image. For instance, when consumers posted negative blogs accusing Dell of having poor customer service, the computer company created IdeaStorm, a website where unhappy Dell users could post their problems, share ideas with the company, and even help other customers. The company succeeded in cutting the number of negative blog posts from 49 percent to 22 percent.[22]

With the widespread use of the Web and the emergence of social media, even companies innocent of wrongdoing can become victims of negative publicity. Jamba Juice is a California-based company that advertises its "healthy blended beverages, juices, and good-for-you-snacks." So when a blog known as The Consumerist reported that Jamba Juice used milk in its nondairy smoothies, an outcry was unleashed. The blog posting was linked to twenty other blogs and read twenty-three thousand times. It turned out that the information was incorrect. Jamba Juice called The Consumerist to say the information was wrong but did not post anything on its own website.

The Consumerist did correct the story on its blog, but the accusation against Jamba Juice was viewed by six times as many people as the correction.[23] Had Jamba Juice paid more attention to blog reports about one of its products, it could have minimized the damage to its reputation. "A lie can travel halfway around the world, while the truth is still putting on its shoes," Mark Twain said more than a century ago. Consider the relevance of his statement in today's connected world.

Simply focusing on what to say when there is controversy serves only to distract spokespeople from addressing the larger question of how they want to be seen by the audiences they care about—shareholders, customers, suppliers, bankers, employees, and the public. With these stakeholders, there is little to gain by appearing in the media as defensive, argumentative, or unresponsive. Even Steven Jobs, considered one of the most visionary business leaders of our time, has faltered when pressed by a persistent journalist.

Several years ago, Jobs's company Apple was rudderless without a CEO. CNBC offered Jobs an interview, which provided him with an opportunity to boost investor confidence. Before the live on-air interview began, Jobs told the interviewer he did not want to talk about the search for a new Apple CEO. Did he truly believe that by telling a reporter he didn't want to talk about something, the reporter would stay off the subject? If anything, it makes the question more tempting because it obviously touches a nerve. After a few questions about foreign markets, the interviewer predictably turned to the prohibited topic:

- Interviewer:

Okay, and the other area everyone wants to know about is the CEO search. What's the status there?

- Jobs:

We're going along as planned and we're continuing to look.

- Interviewer:

The perception is the short list has been exhausted, and out of the good choices a couple of good candidates slipped through your fingers. Is the search in disarray right now?

- Jobs:

Well, you see, you should talk to them if you think they know. I . . . it's a very different view.

- Interviewer:

I think a lot of people do think it's not going too well. Is that an incorrect perception?

- Jobs:

It's not my perception.

- Interviewer:

Have you ruled out totally the idea of taking the job?

- Jobs:

We agreed we weren't going to talk about that.

Jobs then whips off his lavaliere microphone, flicks it away, gets up, and leaves the set live, on the air.

- Interviewer:

All right, Steve, thank you very much. Steven Jobs live from San Francisco.

The CNBC encounter with Jobs made for compelling TV. Investors and analysts watched Jobs come across as angry and petulant—not a good way to project himself, especially in front of the international investment community. Apple's stock price dropped almost 30 percent in the following month, closing at a split-adjusted low of $3.23 per share.

Knowing how you want to be perceived is a critical starting point for both answering questions when a controversial situation arises and shaping an overall, long-term media strategy. Clearly, there is much to be gained by projecting an image of openness, honesty, and empathy. Much of your success in conveying these qualities and influencing public perception depends on tone. Following are the stories of two companies caught in a public controversy over offensive advertising campaigns. The first company is Dairy Queen, a leading restaurant chain specializing in ice cream. The second company is Tim Hortons, a coffee and donut chain.

The offending Dairy Queen ad featured a boy flailing on a hook that hung on the back of a door while his older brother laughed and ate ice cream. The ad was not funny to the Neuts family, whose ten-year-old son Miles died after being hung on a hook at school. The family approached the company, demanding the ad be pulled. When Dairy Queen refused, the boy's father called for a North American–wide boycott of the ice cream chain. Finally, Dairy Queen agreed to pull the commercial in the town where the Neuts family lived.[24]

Contrast Dairy Queen's handling of the situation with the response that Tim Hortons offered in a controversy it faced. Free coffee mugs were the giveaway in the "Get Mugged with Tim Hortons" contest, but the play on words did not sit well with the family of Erin Sperrey, who had been beaten to death while on the night shift at the Tim Hortons in Caribou, Maine. Erin's mother sent Tim Hortons an e-mail: "I am appalled that you would dare use a reference to violence in your advertising campaign. If you are going to do that, why don't you go all the way and make it, 'Get Mugged and Murdered with Tim Hortons?'"[25]

A typical or traditional PR response to this kind of controversy may have been, "It wasn't our intention to offend anyone. Our mug contest is simply a fun promotion." Instead, company spokesman Nick Javor recognized the depth of feeling and personally apologized to the family and then publicly apologized. "It was a poor choice of words for a promotion anywhere," said Javor. "We feel awful."

In the first example, Dairy Queen disregarded the Neuts family tragedy and came across as arrogant and indifferent. The company's denial incited a public dispute that nearly resulted in a significant loss of reputation and business. Tim Hortons, in contrast, responded in a way that made the company appear responsive and humane. Its compassionate handling of the controversy led to a swift resolution that drew praise from victim advocacy groups. How did Tim Hortons decide to take this tack? They asked themselves one of the most important questions to consider when managing a public relations crisis.

In counseling clients in crisis, there is one question I always ask: "Money aside and lawyers aside, what's the right thing to do?" This is all the more important when people suffer or experience harm as a result of an action by a company. In such situations, it is vital that corporate figureheads take responsibility for their company's mistakes and fix them. That question and the answer that went with it were front and center in the work I did with PG&E in what has come to be known as the Erin Brockovich case.

In the 1950s, '60s, and '70s, Pacific Gas & Electric, the California utility that is a subsidiary of PG&E Corporation, used chromium, a rust inhibitor, in cooling towers at gas compressor stations in remote parts of its service area. Wastewater containing the chromium was put into unlined pools at those sites. The practice was both common and legal.

Over the years, the chromium made its way into the groundwater in those areas, contaminating the drinking water supply. Some PG&E employees became aware of the problem in the 1960s, but they did not share the information with others in the company or with the public. Years later, in the late 1980s, a number of families came forward, insisting they were suffering high rates of disease, which were later blamed on their exposure to chromium. They filed a class-action lawsuit against PG&E.

The right thing to do in the Erin Brockovich situation, at the very least, was to acknowledge the suffering of members of the community. However, in situations of this nature, most lawyers instinctively want to put up a wall and not go anywhere near acknowledging the pain, suffering, or inconvenience others may have experienced due to something the company may or may not have done, even if the alleged misdeed took place a generation ago.

The leadership in place at the time when the Erin Brockovich case came to the fore recognized the need to confront the situation in a manner that displayed sensitivity to the concerns of community members. Even though they were not convinced that the company was responsible for ailments in the community, PG&E's leaders, along with the company's public affairs executives, wanted their messaging to reflect an empathetic tone.

After the plaintiffs secured a settlement from PG&E, company chairman and CEO Peter Darbee said it was important to "act with integrity and communicate honestly and openly." Darbee's words matched his values. "We know this case has been difficult and emotional for the plaintiffs and their families," he said. "We are accountable for all of our own actions; these include safety, protecting the environment, and supporting our communities." Darbee went on to say, "This situation should never have happened and we are sorry that it did. It is not the way we do business, and I believe it would not happen in our company today" (Peter Darbee, e-mail message to employees, February 3, 2006). With those heartfelt words, Peter Darbee acknowledged the community's hardship and earned the trust of his stakeholding public on a very emotional issue.

Today, more companies and organizations are moving toward this open, empathetic approach. When it turned out that Biogen Idec's potential blockbuster drug for multiple sclerosis, Tysabri, may have been responsible for a rare brain disease in three patients, CEO James C. Mullen alerted the FDA, suspended sales, and initiated a review of all three thousand patients in its clinical trials. "Here was a risk that we didn't understand," said Mullen. "Stopping the drug was the right thing to do."[26]

Sometimes, doing the right thing can involve going against conventional wisdom. Even when his trucking company clients are clearly liable in fatal road accidents, Tennessee lawyer Jim Golden reaches out to family members of victims "just to say we're sorry for your loss." Though his legal colleagues claim such an action will damage their negotiating position, Golden says it helps to "break the wall of silence." The result has been a profound reduction in the number of claims and the cost of claims, with some of his clients achieving 20 to 30 percent savings in insurance premiums. One large company that manufactures products such as lawn mowers has saved $50 million on product liability claims and $6 million in insurance premiums since adopting this more open approach.

The one constant in all of these examples is that each company or organization elected to take responsibility for its mistake regardless of costs or damages. Doing so was especially meaningful when lives were at stake. Unfortunately, doing the right thing can be an elusive concept, particularly during times of crisis. But all of these companies chose to do the right thing and subsequently enhanced their credibility by matching their actions, policies, and messages to a set of fundamental values.

Managing your image and reputation in difficult times requires firmly held values brought to life by words and actions. A focus on values illuminates ways to build confidence with stakeholders, especially when managing issues of high concern and low trust. Recalibrating to fundamental values will lead you to pathways that offer clarity on what needs to be said and done.

When Nancy Daigneault became president of mychoice.ca, a Canadian smokers' rights group, she knew she was in for criticism, not only from media and special interest groups but also from friends and family. Mychoice.ca is funded by tobacco companies, which are about as popular as pigs at a bar mitzvah.

Daigneault, a nonsmoker, said the website would give voice to the concerns of Canadian smokers, who face growing government smoking bans as well as personal demonization. "Smokers have the same rights as everyone else to be consulted and to have their concerns taken into account—but you wouldn't know it from the way they are treated," said Daigneault. "Banks, businesses, professions, and all kinds of different groups in society are able to influence public policy by banding together and speaking out clearly to make sure politicians cannot ignore their concerns," Daigneault said. "Why shouldn't Canada's five million adult smokers be able to do the same?" The mychoice.ca website would not promote smoking but rather would provide links to quit-smoking programs. "I am a former smoker who quit because of the health risks involved and would not be part of anything that encouraged people to smoke," she said.

When the Ontario Medical Association called for a ban on smoking in cars carrying kids, Daigneault was invited to comment on an afternoon radio show. Going into the interview, she knew there were three messages she wanted to deliver:

"No one would advocate smoking in cars with kids."

"Smokers care about and love their children just as much as nonsmokers and should take this advice."

"Public education is a better way to let smokers know they shouldn't smoke in cars carrying kids."

Daigneault's advisers did not want her to deliver the first message. They felt that saying no one would advocate smoking in a car with kids would confirm that a problem actually exists. Uncomfortable with the advice, Daigneault took it anyway. As a result, she came across in a manner that suggested she actually supported smoking in cars with kids. "I became somewhat defensive and probably sounded angry during the interview," she told me later. "After the interview, I told my advisers that I would, in subsequent interviews, deliver message number one. Later that day, I did at least ten other interviews and delivered all the messages I wanted to deliver and the interviews were fine. Without the first message, I sounded like a crazy person who thought it was okay to smoke with kids in the car."

As Daigneault discovered, it can be a mistake to abandon one's values in the face of controversy. This is particularly true in situations that present a clear moral or ethical position. Obviously, smoking in cars when children are present is one such issue; it really doesn't have two sides to it. While Daigneault's mistake was easily corrected by readjusting her message to fit her values, it could have just as easily been avoided. As she later admitted, "I didn't pull out my Value Compass and I got a bit burned."

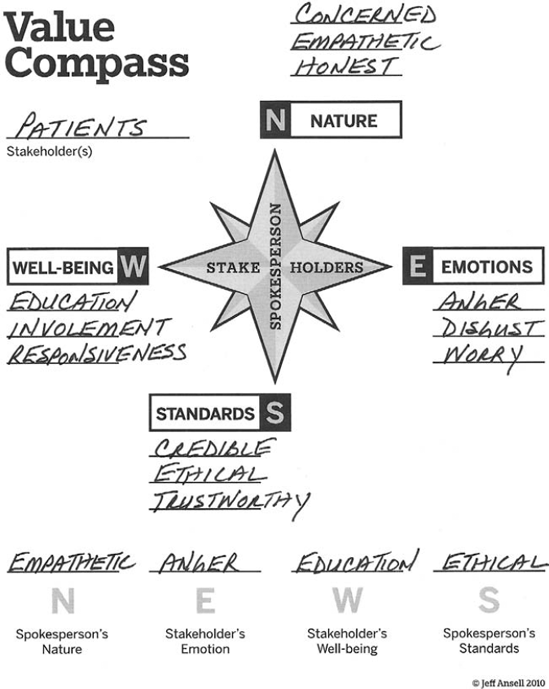

The Value Compass, pictured in Figure 2.1, is a powerful tool to help you deal with public battles and situations that are unlikely to be won in the court of public opinion. When the public's trust is threatened, the compass is a guide or road map to meaningful, honest responses that present you and your organization in a positive way.

There are three basic components of the Value Compass: the blank "stakeholders" line near the top of the form, the actual "compass" and its four corresponding directions, and the four blank spaces above the "NEWS" acronym at the bottom. The "stakeholder(s)" line is used to identify the people most affected by the news event in question. The compass itself indicates four directions, or categories, presented on two primary axes. The north-south axis represents the (N)ature and (S)tandards of the spokesperson and her organization. These two categories help the spokesperson identify the image and traits her organization wants to project to the media and public. The east-west axis, in contrast, represents the (E)motions and (W)ell-being of stakeholders. Identifying and understanding the perspective of stakeholders helps you in framing responsive messages and matching future actions to stakeholder needs. Three words should be selected for each category. Then, from these three words, one word that best applies to the current news event should be chosen and placed in the appropriate blank at the bottom. Once in place, all decisions, actions, and communications are screened through the "NEWS" filter created by these four Value Compass terms.

If this all sounds a bit overwhelming, don't worry. Detailed, step-by-step directions for creating your own Value Compass follow a little later in this chapter. In addition, an abridged set of directions is included with the blank Value Compass in the Messaging Tool Kit in the Appendix. Sometimes thinking of appropriate Value Compass words can be challenging, so I've provided a list of the twenty words most echoed by clients in my practice for each category. Table 2.1 shows a partial list of these terms. For the complete list, see the Appendix.

Of course, this is only a guide. When you create your own Value Compass, use any words you find most applicable to your specific circumstances. Key words from your organization's mission or vision statement often work well. The terms I provide here should be considered a starting point as you determine how you want to be perceived by the media and public. To create your own Value Compass, use the following step-by-step instructions.

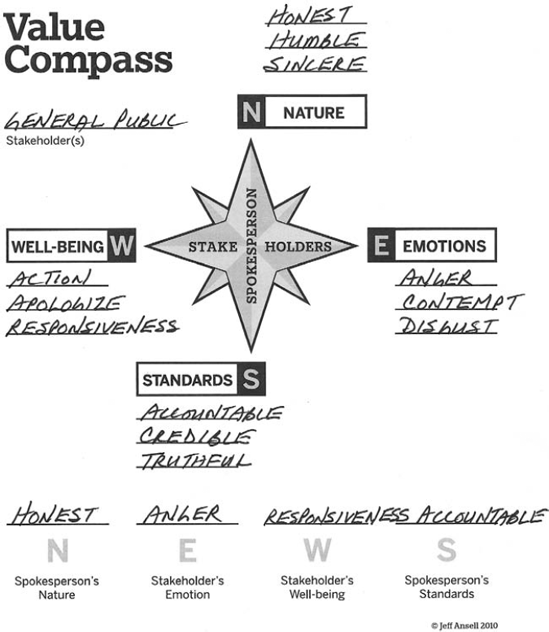

Figure 2.2 presents a completed Value Compass created by a recent client of mine. Working in a controversial industry within the consumer staples sector, this client was accused of tax evasion and pled guilty to a $200 million fine. To help deal with upcoming public relations events, the company's director of corporate affairs created the following Value Compass:

Now the client can filter future messages through the four chosen Value Compass words to ensure media messages match organizational values. Is the message honest? Does it acknowledge the general public's anger? Is it responsive to stakeholders' needs? Does it reflect the organization's accountability? If so, then the client knows those organizational messages will help build stakeholder confidence and trust.

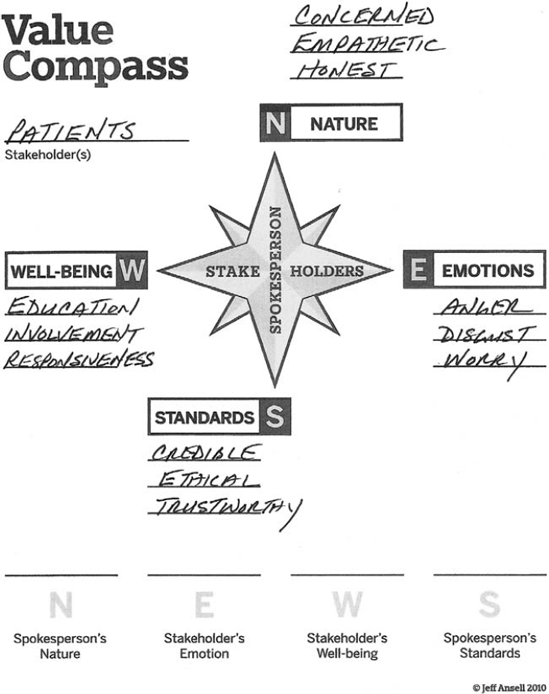

Remember Joan Smith, the chief executive officer for biopharmaceutical company JLA Life Sciences? As we saw in Chapter One, she was questioned about the price and availability of Biojax, a new and highly effective biological drug for treating cancer. Joan was convinced she had a positive story to tell, but she discovered that an interview can quickly turn antagonistic. Fortunately for Joan, she will get another chance in Chapter Six to address concerns surrounding Biojax. To prepare for her interview do-over, Joan needs to create a Value Compass. During one of our sessions, I sat down with Joan to help her through the six steps just outlined.

First, we spent some time identifying her stakeholders. For a new biological therapy, her stakeholders could be the general public or doctors or health care payers. They could be patients, their families, or activist groups. To narrow down the options, I asked her who was most affected by the price and availability of Biojax.

"Patients," she said.

"Why patients?" I asked.

"They're the ones with the most at stake. They're fighting for their lives."

"True, but are they the group you most hope to reach through the interview?"

"I don't know. I hope to reach everyone."

"No, I mean if you had to pick one group you hope will read the story, would it be patients?"

She thought about it, then nodded. "Yes, absolutely. Patients are the ones who need to mobilize and help pressure the government and insurance companies to add Biojax to their reimbursement list."

With that settled, we focused on the spokesperson axis. Starting with (N)ature, Joan read through the Value Compass words list. After a few stops and starts, she chose concerned, empathetic, and honest.

I asked her why she chose those three words.

She said the impression she had was that people felt JLA Life Sciences was callous and deceptive in its pricing practices. "People don't understand the costs and challenges in bringing a new drug to market," she explained. "We're being honest and up-front about those costs. People made a lot of sacrifices and they deserve to be rewarded. But that doesn't mean we don't appreciate the feelings of patients. We do. We're concerned about patients and we understand the difficulties they face."

Next, Joan read through the possible words for (S)tandards. The terms that stood out to her were credible, ethical, and trustworthy. She felt these three words represented corporate standards that countered the impression that JLA Life Sciences was dishonest and heartless. "We really are trying to do the right thing," she said. "We're trying to help people live longer, better lives."

With the spokesperson axis complete, we shifted to the stakeholders axis. I asked what emotions her stakeholders might feel while listening to a discussion about the price and availability of Biojax. "In other words," I said, "if you were a cancer patient, how would you feel?"

"I'd be angry."

"Why?"

"Because here's this product that can help me, that's proven to lengthen lives, but I can't get it."

"What else?"

"I'd be disgusted. I mean, this looks like another case of corporate greed. And I guess I'd be worried, too."

"Worried about what?"

"About my future. About my family and how long I have to live."

"Those are all very strong emotions."

"No kidding," Joan said grimly. After she filled in the three lines for (E)motions, we moved to the stakeholders' (W)ell-being. I asked her what she thought JLA Life Sciences could do to enhance the well-being of people who are angry, disgusted, and worried.

"Be responsive," she replied almost immediately. "Patients need to know we're listening. That we care."

"And?"

"And—" She scanned through the list of words.

"Let me put it another way," I said. "These are people fighting for their lives, right?"

"Yes, absolutely."

"To help with that fight, what do they most need?"

"Biojax," Joan said. "But we can't just give it away."

"Then how can patients get it?"

Joan's face brightened. "By getting involved. They need to write their representatives. They need to join cancer activist groups and put pressure on the government and insurance companies to pay for Biojax."

"Can you help them do those things?" I asked.

"Sure, I guess."

"How?"

"I see where this is going," Joan said, smiling. "We can help by educating patients. By telling them who to contact and providing the information they need to leverage decision makers." She filled in the remaining blanks on the stakeholder axis. This may seem like a somewhat involved process, but it actually took less than five minutes. Figure 2.3 shows how Joan's Value Compass looked at this point.

Now it was time to choose one word from each category. Often, this seems like the hardest part. As Joan said at the time: "They all look like good words."

I told her not to worry. It's actually easier than it appears. "Let's just take a few minutes to work through each category," I suggested.

We started with (N)ature. Although it was important to be honest and concerned, Joan decided it was most important to appear empathetic. "If we're empathetic, if we make it clear we understand their challenges and fears, then patients will know JLA Life Sciences is on their side."

The (E)motions category was even easier. "More than anything, patients are angry," Joan said. "They feel powerless. They feel like they're being taken advantage of or sacrificed."

When we moved to (W)ell-being, Joan said, "I guess I've already figured this one out. Patients need to get involved. They need to begin changing policy."

"I know," Joan interrupted. "To do those things, they need education." She wrote education in the blank line above "W."

Last, we addressed (S)tandards. Joan carefully considered the three options. "When profits and medicine are mixed," she said, "it's always an issue of ethics. People are questioning our motives. It's important that we make it clear to patients that above all else, we're ethical."

With a clear understanding of how she wants her organization to be perceived and valuable insight into her stakeholders' perspective, Joan is now ready to begin addressing her critics. Joan's final Value Compass is presented in Figure 2.4.

When people mired in bad news are asked to identify the words in their Value Compass, the same terms are often used. Predictably, most people say they want to be seen as sincere, honest, credible, and competent. What separates people and organizations, however, is not the words they choose to describe their values but rather how they express and implement those values. The next few chapters provide specific tools and strategies for transforming your chosen values into messages that convert words into commitments and commitments into action.

When a reporter makes contact, follow these three steps: be friendly, create a buffer zone, and ask questions to determine her or his intentions.

When talking to a reporter, be careful of what you say and remember there's no such thing as "off the record." When in doubt, leave it out.

To better manage your image, follow what others are saying about your company or organization in the media, on the Web, and in blogs.

Be aware of how you come across. There's no benefit to being seen as defensive, argumentative, or unresponsive. Instead, project an image of openness, honesty, and empathy.

To project a positive image, first ask yourself, "What's the right thing to do?"

To ensure that you're doing the right thing, look to your values. The Value Compass is an effective tool for establishing and focusing your values, particularly when public trust is threatened.