"It's all in your head." How many times have we all heard that? Well, guess what? It is! Whether you are talking about good things or bad things, feelings, thoughts, ideas, or even just how your body is working or is not working, it really is all in your head. Am I saying you're imagining everything? Not at all. Let's be very clear what we are addressing here. Just what is in your head?

The cranium is the part of the skull that encloses the brain. It's been a long time since most of us have explored the basics of the nervous system, so here's a quick review: Your brain contains 15 billion to 33 billion neurons, each of them linking with as many as 10,000 synapses. These neurons communicate via protoplasmic fibers called axons that pulse messages to distant body parts. The brain controls all the body's physical and mental functioning—its F.A.T.E. Housed deep within the brain are almond-shaped nuclei called "amygdalae." This is the seat of your fight-or-flight mechanism—your basic adaptive reaction to physical or emotional stress. Much research regarding the biology of social anxiety has focused on that area, which is known to play a primary role in processing emotional reactions.

Bear with me a little longer—I realize you didn't pick up this book because you were looking to brush up on neuroscience. But this is important stuff. This is your brain we're talking about! And it's all in your head.

Here's what I mean: The five mind states we have been discussing exist within your brain. The F.A.T.E. dimensions of each of those mind states have a biological base. They exist physically—maybe not as individual "almond-shaped nuclei," but they are sourced from a physical organ that has a capacity for health and a capacity for illness. Doesn't it make the ultimate sense in the world to take care of—or nurture—the biological structure of the brain?

... whether you are aware of that thought or not. The more you learn to take conscious responsibility for your thinking, the more you can invest in developing a High Performance Mind. As humans, we tend to have a running monologue going all day long. Our mind states—NP, CP, A, AC, and NC—assert themselves in various ways:

Nurturing Parent: | "Have a healthy breakfast—you need the energy!" |

Critical Parent: | "Don't eat junk food!" |

Adult: | "It's breakfast time." |

Adapted Child: | "I'm a pig for eating this doughnut." |

Natural Child: | "I want that doughnut!" |

Five different thoughts about the same thing—breakfast. Five valuable perspectives. How do you balance the five scripts? Take conscious responsibility for them. Remember, all five mind states are essential, so it is not a matter of drowning out or ignoring one mind state or another. Rather, it is a matter of adjusting the dials so that these mind states are in balance.

Here's an example from my own life. I love a great bottle of wine (only white; red gives me headaches), such as a Montrachet or Corton Charlemagne. But I consciously limit my drinking. At the end of a nice weekend, I would really enjoy sitting down with a few glasses of wine on a Sunday evening. My CP says to be cautious—there is a workweek ahead. My NP says to do what is best to get a good start on the week. My A makes me aware of things such as what time my Monday appointment schedule starts and what effect alcohol—even just a glass or two—might have on my brain health (making it harder to fall asleep, for example). My AC mind state notes that having a drink against my better judgment could make me less effective. And my NC is telling me how much I enjoy wine and how great it would be to have a glass right now!

Over the years, I have factored in the scripts from all these mind states, all of which have valuable contributions to make. The bottom line? I choose not to drink on "school nights." I am not talking about getting drunk; I am just making clear that alcohol can be an inhibitor, depressing overall brain functioning and decreasing all five mind states. Paying attention to my brain health is better for my therapeutic work. It's better for writing this book, since accessing my creativity and organizing my thinking takes brain energy. The same with working out. I want my brain in top working condition! This is not to say you must make this same choice—so long as you think it through from a mind states perspective. A healthy brain requires conscious thinking and decision making. I want my neurons, protoplasmic fibers, and amygdala working as well as possible. I want to nurture brain health as much as I can. How about you?

You know at this point that all the mind states are important. Each contains specific energy, and this energy is finite—not unlimited. Take a look at the unbalanced mind states graph again (Figure 3.1). This is your mind states graph. See the twin towers—Critical Parent and Adapted Child? You already have way more of the Critical Parent and Adapted Child energy than you need. Don't worry about that for now. You do not need to do anything to decrease that energy. The goal is to grow and develop the Nurturing Parent, Adult, and Natural Child. When you do that, the Critical Parent and Adapted Child mind states will naturally reduce in size to the appropriate level (remember, you need all five mind states, so you never want to get rid of those important personality components completely). It's all about balance.

The NP is the energy of promoting growth and providing support. What actions could you take that would grow your Nurturing Parent mind state in a way that will help resolve your workplace anxiety? The following ideas are presented in systematic order. Read each one thoughtfully, pausing to complete the questions along the way before proceeding to the next. Do not detach from a concept or question! Stay with it. Take a deep breath in and out to concentrate as you encounter each new idea.

Invest in good brain health. Invest your time and energy in working through this program, which includes both the carefully designed exercises you have completed so far and the remaining material in this book.

Integrate the belief that your most valuable asset in life is time into your thinking and decision making. Life is not a dress rehearsal. Play quarterback. Be the pilot. As you take responsibility for creating motion, you will be in the process of gaining control. Passivity creates more worry, frustration, anger, and poor self-esteem.

Cultivate the interpretation that mistakes and failures are part of the learning process. If you want to be good at anything—controlling anxiety, public speaking, relationships, sports, performing arts, communication—you must understand that mistakes are part of skills development. Let go of excessive perfectionist thinking such as "I should never make mistakes." Believing that mistakes or failures are not part of the learning process would be toxic, if not insane thinking.

Embrace your adrenaline as a source of power. Welcome it!

Sustain your efforts with a persistent attitude. The following quotation from U.S. President Calvin Coolidge hangs in my office: "Nothing in the world can take the place of persistence. Talent will not; nothing is more common than unsuccessful men of talent. Genius will not ... the world is full of educated derelicts. Persistence and determination alone are omnipotent. The slogan 'press on' has solved and always will solve the problems of the human race."

Realize that anything you do to promote growth is nurturing; therefore, acknowledge yourself for working through this program and realizing what you did not know. Right now, list three new concepts that you have learned thus far. Can you do six?

1. | |

2. | |

3. |

Invest in attachment. You know that detachment is a defense mechanism anxiety sufferers enact to avoid the pain of feeling. Attach to conscious thinking. Be open to paradoxical thinking—thinking the opposite of what you currently do.

Identify three issues to which you have been attaching since starting this book:

1. | |

2. | |

3. |

Need some examples to get you started? After Amy completed this exercise, she made the following two entries about what she had begun attaching to and—extra credit!—the paradoxical thinking she had opened up to.

Scheduling my time. Paradoxical thinking: Planning carefully gives me freedom.

Asking for help. Paradoxical thinking: It is smart to ask questions—rather than dumb not to already know the answers!

Become an expert at identifying (via attachment) your emotions. Make the Feelings List your bible. The more you attach to, identify, and appropriately express emotions, the less you are susceptible to repress and therefore to recycle emotion that drives anxiety, obsessive worry, and mood discomfort.

Develop your awareness of internal physical cues by correlating changes in the skin temperature of your hands to emotions and thinking. (Consider accepting the Biocard offer at www.socialanxiety.com.) Warm hands mean relaxation. Cold hands mean stress—but that can be good stress or bad stress. Use your Adult to recognize that your hand temperature is merely a fact—it is biofeedback information about your physical functioning that lets you tune in and become aware. Adrenaline is not a bad thing.

TUNE IN: Right now identify your skin temperature. Pair it with your thinking and emotion.

Be diligent and precise about learning the self-regulation exercises throughout this program. You must perform each exercise exactly as I describe it—down to the seconds or minutes specified.

Manage your stress. Differentiate between good and bad stress and make stress work for you instead of against you.

Resolve the excessive emotions of embarrassment, humiliation, and fear of rejection.

Understand and resolve your repressed and recycling anger. Express it constructively, and channel it into productive energy.

Validate your achievements! This is crucial for nurturing. We are not talking about boasting; rather, we mean acknowledging yourself for the success you have achieved. It's so easy to focus on negatives and things that do not work out. For example: Jerome taught an IT class at a community college. At semester's end, his 20 students were asked to fill out a course evaluation. Four of the students mentioned that Jerome didn't leave enough time for questions at the end of each class. Sixteen of the students had no complaints, and seven of those said it was the best IT class they had taken. Which feedback did Jerome focus on? The negatives.

Susan, a part-time program coordinator at her church, organized a retreat weekend that 200 people attended; unfortunately, it rained all weekend, which was not what she had envisioned. Even so, the entire group was enjoying the fellowship activities—particularly the improvised indoor scavenger hunt and the fireside sing-along. What did Susan think about? All the outdoor activities she had had to cancel because of the wet weather. Neither Jerome nor Susan was making adequate use of the NP and A mind states, which would have said "Look at all you accomplished!" (NP) and "The entire group participated and the schedule was full" (A). What do you imagine those mind states would have provided by way of encouragement, objective feedback, or playful exploration? Productive performance occurs through focusing on positives.

Right now, think back over the last few months, then list three recent achievements or successes (components of progress).

1. | |

2. | |

3. |

Now list three more achievements that have occurred within the last year.

1. | |

2. | |

3. |

What can you say to acknowledge yourself for these achievements?

Cultivate your sense of humor. Developing your Nurturing Parent mind state allows you to look on the bright side and, with the help of the Adult, to put things into perspective. Ultimately, humor helps us not to take ourselves so seriously. Are you willing to lighten up? To let go? To say, "Oh, well!" and get on with things? Amy recalls turning to her Nurturing Parent, Natural Child, and Adult mind states when a particularly stressful day became even crappier—literally:

I was on deadline with my weekly newspaper column. I finished it in the nick of time and raced over with the disk (this was before the days of e-mail!), took my dog to the vet, then made it back home for a phone appointment, after which I had a half-hour to tighten up a book chapter I was working on before dashing six blocks to meet with the coauthor of a book I was writing about dreams and creativity.

But I sure wasn't feeling very creative. It turned out my audiocassette recorder had malfunctioned, so I had had to rely solely on my interview notes for my column. The vet bill was about $100 more than I was expecting. And I had gotten a parking ticket. By the time I was on my way to my coauthor's office, I was pretty stressed.

Then a bird pooped on my head. In that moment, I could have really lost it from the stress and anxiety of the day. But instead I just started laughing. I took it as a reminder that things could always be a little bit worse. That memory still makes me laugh.

In that moment, Amy accessed her NP—it's almost as though her NP put its arm around her and said with a rueful smile, "See? It's always something!" Amy's Adult mind state was also at work. She stayed in the moment, realizing that it was no use wishing things were different. This was the way things were. You could editorialize and say this was a bad day. Or you could use the A mind state and say this was just a day, neither good nor bad. No reason to come to a complete collapse over a little bird doo!

When was the last time you laughed? Not a smile, not a chuckle—a real laugh that left you a little out of breath and a lot more relaxed? Laughter truly is one of the best medicines there is. The research of Doctors Lee Berk and Stanley Tan of Loma Linda University has shown that laughter has many health benefits: It decreases stress hormones; it loosens muscle tension for up to an hour after the last guffaw; it gives you a natural high by releasing endorphins that enhance feelings of well-being and ease pain; it boosts your immune system by raising the level of infection-fighting T-cells; and it lowers blood pressure. Plus, it's fun!

TUNE IN: Smile! Make it a big, wide, I-can't-help-it smile. How does it feel? Are your hands cold or warm?

Develop realistic expectations. Unrealistic expectations set your inner child up for anger and frustration. List three examples of unrealistic expectations that you have placed on yourself. To get you started, take a look at one of the examples Amy identified while doing this exercise; then complete each step for yourself, entering your responses in your notes.

Unrealistic expectation:

Be able to take on every new task that comes my way

1. | |

2. | |

3. |

The result of these unrealistic expectations was what in terms of behavioral outcomes and your emotions?

Felt guilty and ashamed when I didn't complete everything; compromised the completion of my primary responsibilities and caused me anxiety; had to work extra hours to catch up; annoyed boss by taking on too much.

1. | |

2. | |

3. |

Now change the unrealistic expectation to realistic.

Realistic expectation:

Sometimes I need to say no to a request.

1. | |

2. | |

3. |

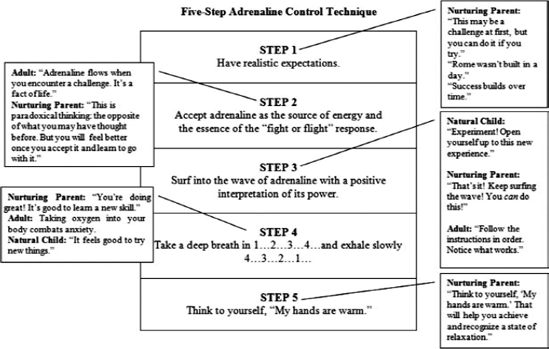

Learn and implement the Five-Step Adrenaline Control Technique described at the end of this chapter.

Work in layers. Often people get overwhelmed when they try to do everything at once. Layering work, doing a little at a time, and working consistently make a nurturing and productive blueprint for success. I learned this concept from a friend back in 1988 in a conversation between basketball games. This person was a best-selling author whose book had been made into a television miniseries; he told me, "Writing is all about layers." He was right. I adapted this dynamic to much of my work and projects in general with much success. Remember that the advice you got about working through this book was to do it the first time within 21 days. Take that time—it is a sufficiently long period, yet not so long that the concepts won't stay fresh. Better you spend 30 minutes or an hour here and there than try to absorb the content in just a few days.

Practice using nurturing messages for confidence building, reassurance, and comfort. Incorporate them into your internal script.

Now that you have a strategy for developing your Nurturing Parent mind state, let's move on to the Adult—the energy of logic and objectivity. Remember, the Adult is not intellectual intelligence. Again, if you are worried about your IQ, don't be: You are intelligent if you have the motivation to improve your performance and control anxiety at work. Unintelligent people simply do not have this desire or motivation.

Here are some exercises for strengthening your Adult mind state:

Develop your objective observation skills

Observe a situation for at least a few minutes in an environment that is not too important to you. You could be waiting in line for a movie, waiting for a train, or going through security at the airport. After you observe, describe in your notes what you saw objectively. Omit any value judgment or feelings; just be neutral.

To get you started, here is an excerpt from Amy's exercise notes; notice where she crossed out the places that included judgment, interpretations, and feelings in favor of sticking with what she knew was objective:

Two people are ahead of me in line for coffee. One is a young woman, wearing a down parka, jeans, and boots; she is being rude to the cashier talking on the phone while she is ordering. One person I am glad to see is my friend Robin, who is glad to see me.

After A, observe for at least a few minutes a more personal scenario such as your office or a family gathering. Then objectively describe it without value judgment or feelings.

Learn from observation

Identify something you learned from a recent observation at work. Write it down, which will help your brain imprint the learning process.

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

Identify something you learned from a past observation at work. Again, write it down:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

Make sure you are actually following through on the exercise. Don't detach!

Use your logic and objective reasoning to hypothesize an answer instead of responding with "I don't know," detaching from, or avoiding the issue altogether. Identify a situation recently at work where you detached from an answer; then hypothesize what the answer would have been.

The situation I detached from:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

What the answer would have been:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

Validate the fact that success is not characterized by a straight line up. There are high points and low ones, steps forward and steps back. Success looks like what's shown in Figure 4.1.

Don't be afraid of the success graph. Success is a process—a journey. Attach to this image as the shape of steady progress. Celebrate the highs, and learn from the lows, and most important, press on!

Identify three past situations where your emotions got in the way of your learning from mistakes or where embarrassment or humiliation impacted objective reasoning and forward movement.

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

Identify options for utilization of logic and objectivity instead of emotion in these scenarios.

1. | |

2. | |

3. |

This is a basic version of a very effective exercise we will return to in an upcoming chapter. For now, practice giving yourself over to the present as you master this 60-second version. Sit in a comfortable chair. Allow yourself to feel passive. Take in a long, slow, deep breath 1 ... 2 ... 3 ... 4 ... then slowly exhale 4 ... 3 ... 2 ... 1.... For the next 60 seconds, focus on your rhythmic breathing, pacing your inhales and exhales to between 8 and 12 seconds. Then say three times, "My right arm is heavy and limp." Then say three times "My left arm is heavy and limp." Close your eyes and repeat the phrases again—three times for each arm. Next, feel yourself sinking into the chair. Feel like a rag doll. Feel loose. Feel limp. Feel very limp. Become comfortable with, and focus on, the sensations of heaviness and limpness for two to three minutes. Then, open your eyes and take a deep breath in and out.

Learn and implement the following problem-solving technique. A good thing to tell yourself is, "Don't stress out about that which is doable." When a problem comes up, the objectivity of your Adult will tell you that with most problems, resolution is possible. Resolving is a process, and it requires proactive thinking. What usually gets in the way is anxiety. It is anxiety that inhibits forward motion. To give yourself courage, apply a nurturing interpretation: Tell yourself that feeling uncomfortable can mean "I am improving my skills," "My self-esteem is improving as I am moving forward," "I will be less angry when I take responsibility for motion instead of being passive," and so on.

Problem-Solving Technique

Identify the problem or stressor.

Identify the cause.

Identify the choices.

Set priorities.

Make a decision.

Follow through.

Keep following through.

Here is an example of the Problem-Solving Technique in action. Caroline was the executive secretary to a bank's senior vice president. When Mike, a midlevel executive, was transferred from another branch, things got a bit complicated. Caroline's anxiety increased because Mike started asking her to do research for him although she was not assigned to him. Caroline found herself falling behind in her own work. She left work daily feeling resentful, angry, and powerless. Here is how she applied the Problem-Solving Technique:

Identify stressor: Mike gets me to do his work for him.

Identify cause: I can't seem to say no.

Identify choices:

Keep doing the work.

Tell the vice president it's an issue.

Go directly to Human Resources.

Get feedback from other colleagues.

Flatly refuse to do the work.

Do it, but make clear that it's extra.

Tell Mike "I'd be glad to, but I have to check with my boss."

Tell Mike "I'll do it as soon as I'm finished with my other work."

Set priorities:

Keep my job!

Get my own work done first; do it as well as I can.

Maintain good working relationship with vice president.

Make a decision:

I will keep it between Mike and me. I will tell him I'm glad to help once my own work is done. Going to HR could backfire. Refusing to help could cause more conflict. If I'm lucky, Mike will learn to do it himself rather than having to wait for my help. I know I'll experience some adrenaline anticipating and following through with Mike. The "nurturing" interpretation of adrenaline as positive energy gives me courage.

Follow through:

The last time Mike asked for help, I did just as planned, and he found another assistant with more time to help him. No hard feelings. Actually he was pretty nice about it, so if I ever do have time, I really wouldn't mind pitching in.

Keep following through:

I have begun to feel less nervous about saying no—and at the same time, Mike seems to have gotten the point, because he asks me less and less.

Caroline succeeded in allowing her Adult to step in to provide a solution that kept the emotion in her Adapted Child from getting out of hand. A key dynamic was her "nurturing" interpretation of adrenaline. She experienced an increased adrenaline flow at two points: first, when she anticipated talking to Mike, and second, when she was about to talk to him. She was able to use the Problem-Solving Technique to ride the adrenaline wave without giving in to any past negative association she had with that feeling.

Give the Problem-Solving Technique a try right now.

Identify problem or stressor: ___________

Identify the cause: _____________________

Identify choices: _______________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

Set priorities:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

Important: Identify the points at which you will face an adrenaline challenge and consider how you'll have to utilize the nurturing interpretation.

Make a decision: __________________

Follow through: ___________________

Keep following through: ___________

Follow through means follow through! This is not merely a practice run. Return to your notes as you follow through and keep following through so you have a record of what worked and what didn't. As with any technique, this one has a learning curve, and practice is critical.

Listen when your Adult tells you there is a difference between performance and identity. This is one of the most profound if not the most profound beliefs necessary for controlling social and performance anxiety.

We've all had times when our performance has not been good. Coping with that has certainly required logic in separating performance from personhood. Kirk Rueter was a pitcher in the major leagues for 13 years, playing for the Montreal Expos and San Francisco Giants. During his career, he won 130 games. Sometime later I had the opportunity to talk with Kirk about performance issues, and I asked him facetiously, "Did you ever have a terribly bad game?"

"I was once pitching against the Colorado Rockies," he recalled. "I was losing 7–0 in the first inning with no outs." Just imagine—a full stadium, on television, everyone focusing attention on a losing effort. I asked him how he dealt with that.

"I have to pitch every fifth day," he said, "so I concentrate on what I have to do to be better then next time out." He makes it sound so easy! But think for a moment. Isn't that the perfect winning psychology? A true example of high performance thinking? So simple, so perfect. What would keep an individual from investing in this thinking? The answer is a too-critical internal script—things you say to yourself in your mind so constantly that you may not be able to consciously hear yourself. But I will teach you to hear that script. And more important, to change it!

Kirk's attitude of focusing on the keys to "doing better the next time out" is characteristic of a winning attitude and proactive thinking. To resolve anxiety and develop confidence and success, you must embrace proactive thinking. Realize that there are some things you do not yet know—and understand that this is good news. Learning something new means you can change what is not working for you and build confidence.

Note

To view a free Webinar in which Kirk Rueter and his wife discuss selective mutism, visit www.socialanxiety.com.

We've all had bad conversations, bad meetings, bad days, bad weeks, bad months, and sometimes even bad years. That's not much of a consolation, but it does tell you something: We got through it. How you performed is not who you are; it's simply how you performed. What gets in the way of this logic are the emotions of embarrassment, humiliation, shame, fear of rejection, and the unhealthy and unproductive expectations of perfection. The capability for embarrassment is substantially exaggerated for the person with social and performance anxiety. The reason for this exaggeration, and often toxicity, is trauma or feeling loss of control, both of which are usually based on an over-concern regarding others' perceptions of you.

Attach to your own feelings of embarrassment. Describe the following situations.

A typical situatiorn that I now dread due to my fear of being embarrassed is

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

What my fear tells me others would be thinking is

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

If I addressed the situation using my Adult mind state, being totally objective and rational, others would be thinking something more like:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

Recall that "projection" refers to putting your thoughts or projecting them onto other people. To give a very simple example, Kathleen dislikes her speaking voice, but instead of consciously realizing that, she instead ascribes that dislike to her colleagues (who may or may not actually feel that way). Another example is Alex, a college student working in a sub shop; he had a very strict manager who appeared to anger easily. Alex's thinking was that this manager, given her constant state of agitation, did not like it when she was asked questions. But Alex didn't ask questions because he thought having questions meant he was ignorant; he was projecting that thought onto the manager.

Using the logic of your Adult, list three scenarios where you hid your feelings from yourself by imagining that that was how another person felt about you:

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

The next state for development is the Natural Child. To review for a moment: This state is the truth of desire, creativity, exploration, discovery, the development of ideas, creativity, spontaneity, as well as basic urges such as sexuality.

Here are some ways to "raise" your Natural Child. To begin, become aware of the times you may have stifled your Natural Child—for either productive reasons (holding back road rage during your morning commute) or less productive ones (refusing to dance at the company holiday party even though you wanted to). Note: There are many questions here, and you will be making many lists, so you should definitely use your notes to answer the following series of questions.

Acting on a desire

List as many examples as possible where you did not act on a desire.

List as many examples as possible where you want to act on a desire.

Expressing yourself

List as many examples as possible where you wanted to express yourself verbally but did not because of anxiety (worrying what others would think, fear of saying something stupid, etc.).

List as many examples as you can where you want to express yourself verbally.

List as many examples as you can where you wanted to explore something (a relationship, a problem to solve, a challenge scenario) but you did not because of anxiety.

List as many examples as you can where you want to explore.

List as many examples as you can where you wanted to be spontaneous but censored or stopped yourself because of anxiety (in the last day, week, month, year).

List the activities that you want to do for fun, recreation, and enjoyment.

Give as many examples as you can of situations where you used your instinct well.

Make a list of ideas you need to develop.

Make a list of where, or to whom, you need to express your feelings instead of detaching.

These lists will become an important part of your behavioral game plan as you learn to implement the Five-Step Adrenaline Control Technique.

An important tip: On a daily basis, take a minute or two to identify in your notes examples of how you engaged (and therefore increased) your Nurturing Parent, Adult, and Natural Child. If you like, you can write in more detail.

Realistic expectations are a necessity for anxiety management and confidence at work. Realistic expectations are nurturing. Your adrenaline is going to be there when you encounter anxiety challenges. That's a fact; knowing it is using your Adult. You'd better learn to accept and embrace this reality. Acceptance is nurturing. Investing in the interpretation that adrenaline is your friend and source of power is also nurturing. Believing that the adrenaline should not be there is characteristic of the unrealistic standards of the excessive Critical Parent. This unrealistic thinking will set your Adapted Child up for a temper tantrum of panic and anxiety. Non-acceptance of the adrenaline—getting angry and frustrated with it when you experience it—is the excessive Critical Parent telling you it should not be there. Your Adult will confirm that adrenaline is a source of power; therefore, accepting it makes a lot more sense than rejecting it.

Experimenting with Mind State Balancing is itself a process of nurturing your Natural Child. Creating a hierarchy of anxiety challenges will require use of your Adult's objective analysis. Learning breathing, acceptance, and surfing/acceptance skills are nurturing activities. Being proactive at implementing and sustaining the Five-Step Adrenaline Control Technique is nurturing. (See Figure 4.2.) Adult (logic) will tell you that implementation must be sustained in order to truly learn confidence with the skill. Your A will tell you that you have to feel or attach to whatever you wish to control (in this case, adrenaline). You can't do it via osmosis (as your Adult knows!).

"After my first panic attack," says Anne, office manager at a medical practice, "I could not stop thinking about when it would happen again—not whether it would happen, but when." Anne felt tension as soon as she pulled into the parking lot and she stayed on edge all the time—prepared for fight or flight.

The clinical term for that sense of defensive arousal is "hyper vigilance." It is typical of panic attack sufferers to become hyper vigilant even after just one panic attack. Essentially, the nervous system is on overdrive, consciously or unconsciously expecting a threat to occur. Hyper vigilance integrates thoughts, feelings, and physiology. Anne's thoughts raced, her emotions were close to the surface, and she felt physically uncomfortable.

Anne worked six days per week and had not taken time off in many months. With so little down time she was seldom able to come out of this state. It was a typical vicious circle: The more time she spent in hyper vigilance, the more her energy depleted, and the more susceptible she became to both panic attacks and burnout.

Some people's hyper vigilance begins with childhood expectations of perfection. When a child grows up believing he or she must be perfect to be valued, the slightest slip-up can cause anxiety. Demanding parents only reinforce this response. For some children, the pressure leads to high achievement coupled with high anxiety; for others, it leads to a kind of paralysis—doing nothing at all (avoiding) so as to do nothing wrong.

Sean was the oldest son of two college professors who had high academic expectations for him from the time he was a kindergartner. At the age of 30 and a self-described "IT geek," Sean said his ongoing nervousness at interacting with colleagues and customers felt natural to him: "My parents often had professors over when I was little," he told me. "I was shy around them. I sort of hid behind my mom. I guess she was trying to make light of it when she would tell them, 'Don't ask Sean where he goes to school or what grade he's in. Apparently he doesn't know!' That always got a big laugh. She may not have meant anything by it. But the feeling I get at work is the same feeling I had back then."

Sometimes, serious childhood trauma causes hyper vigilance—whether the trauma is abuse, neglect, or loss of a loved one. Extreme embarrassment or rejection early in life are traumas too. Trauma imprints the brain with a familiar and terrifying feeling. A person who was bullied as a child, for example, may feel bullied by his or her boss. In people who were sexually abused as children, hyper vigilance is quite common. Norma, a 45-year-old middle manager in a market research company, suffered from public speaking anxiety; she never realized the problem was her unresolved emotional conflict, anger, and hyper vigilance resulting from her stepfather's sexually abusing her during her adolescence. Children who grow up in a home environment characterized by discord, conflict, and fighting also become conditioned toward hyper vigilance. They will develop vigilance as a defense mechanism—in answer to some unconscious thinking that goes something like "When will I have to defend myself next?" "When will the peace be broken?"

TUNE IN: Use your Adult to identify a scenario from the past (childhood or more recently) in which you may have learned hyper vigilance. Can you remember two or three?

When ____________, I felt ____________, and I reacted by ________.

When __________, I felt _________, and I reacted by_________.

When ___________, I felt ___________, and I reacted by___________.

Let's do a memory exercise. Go back as far as you can in your memory—back to your childhood if possible—and identify a scenario where you felt a loss of control, panic, embarrassment, or uncomfortable rejection. Notice how you made a negative association to adrenaline. Recognize the hyper vigilance that could have resulted from this scenario.

You probably remember Carol, the ovarian cancer survivor who said she preferred chemotherapy to public speaking. She traced her workplace anxiety to a grade school experience in which her teacher pointed out that she was blushing during class. Jerry, the military surgeon mentioned in Chapter 1, also had public speaking anxiety; his had manifested itself on hospital "rounds" with his peers as well as in formal clinical presentations. His father was an alcoholic who often displayed unhealthy and inappropriate behavior such as attending Jerry's medical school graduation drunk. Jerry learned to be on guard and hyper vigilant from a young age. This hyper vigilance was accompanied by adrenaline flow, which registered as anxiety. In a public speaking challenge, Jerry's critical script said, "There's going to be danger," "Be on guard," "You will be nervous and embarrassed." His learned anxiety and deep negative imprint of adrenaline existed in his AC mind state.

The more this CP–AC syndrome of hyper vigilance and excessive nervous system activity occurs over time, the deeper and more ingrained a reflex it becomes. It can become automatic, which is why the NP, A, and NC need to be consciously developed. This reflex can be the result of ongoing hyper vigilance or, in some cases, one-time trauma.

When I asked Amy what early memories she had that could have led to hyper vigilance, she told me this.

When I was three, I was the littlest kid in the neighborhood. All my friends were five or six years old. When the group of girls would get together to play, the older sister of one of them (she was maybe eight) would always seek me out and punch me in the stomach when no one was looking. I'm talking hard! I never cried, never said a word—I was that determined to be one of the "big girls." My defensiveness when Ana was around definitely reminds me of the hyper vigilant feeling I have had in certain work or social situations: "Brace yourself for whatever's coming next," "Don't trust anybody," "Keep your fears and feelings to yourself," "Big girls don't cry"—all that stuff. It amazes me that my hyper vigilance of today has its roots in such a long-ago experience. I had forgotten all about Ana until I started working on this part of the program.

The following story of my appearance on the Opie & Anthony radio show represents productive mind state balance.

Warning! This is an X-rated story told as exactly and graphically as I can remember.

A few years ago, a PR firm booked me on this show. The PR firm did not tell me the nature of the show, and I had not done any research—which demonstrated not enough Adult and too much Adapted Child on my part. It would have been more effective for me to use the logic of my Adult to do some research about that particular show. But I was rocking and rolling in general—going with my Natural Child—doing a lot of shows, one after the other. Frankly, I was a little too cocky; I felt like I could handle anything, and it didn't occur to me to stop and use my Adult to decide which shows were truly worth my time and energy. All I knew was that Opie and Anthony was on a good station in New York with a substantial audience. I was completely unaware that Opie and Anthony were two shock jocks who made Howard Stern look tame.

I was waiting to do the show by telephone from my home in East Hampton. My wife was in New York, where she heard the promos for "Bad Guest Day." The purpose of the show was to embarrass and humiliate the guests—the hosts' Natural Child instincts gone wild. It was an ambush! My wife tried calling to warn me, but was unable to reach me. The phone rang. I started the interview with my usual two-to-three-minute introduction geared to generate audience attention on the subject of social anxiety.

The first listener call came in: a man who sounded like he was in his twenties. "Doc, can you tell me how I can get the guy in the urinal next to me to hold my penis?" My response after a moment of thought? "I guess you need assertiveness skills."

The next caller: "Doc, how can I get my girlfriend to bend over?" "What do you mean?" I responded. "To have anal sex," he said. After another moment of thought, my response was, "You need to teach her how to relax."

At this point, realizing something was a bit screwy (Adult), I went on the offensive (Natural Child), saying, with a hint of humor, "You know, I work with a lot of socially handicapped people; it sounds like you have many in your audience." To top it off, after subjecting me to this absurdity, they bleeped out my 800 number as the show ended. Opie and Anthony were eventually taken off the air for orchestrating a couple having sex in a church (more primitive Natural Child) and putting it on air. They are since back in action.

There are two clinical points to this story. They are profoundly important for the resolution of performance anxiety.

Opie and Anthony were trying to humiliate me. They orchestrated their attempt very well. But they were not successful. Embarrassment is an internal dynamic. I was angry, but I was not embarrassed. A person can't embarrass you. Yet they can provide a stimulus. You decide. Humiliation is a result of the Critical Parent–Adapted Child interaction, the twin towers on the graph. You and I determine internally if we will or will not be embarrassed by an external stimulus. To paraphrase Eleanor Roosevelt: "No one can insult me without my permission."

After I'd cooled off a little, I took some time to analyze my performance objectively (Adult). I realized I was pleased with my performance (Nurturing Parent), especially my creative answers under stress (Natural Child). I had by then done hundreds of shows, so I was adept at controlling adrenaline and performance stress. I was able to be centered under pressure enough to access my creativity, my Natural Child, and keep from getting rattled on air by this ambush.

In other words I had become relatively desensitized to the stress of performance. This was the result of developing my Natural Child over time. I had given myself a lot of permission to experiment, explore, and discover during my many years of public speaking experience. I had taken a Nurturing Parent approach to performance by seeking out ways to develop performance skills and I was able to access my creativity (Natural Child) under stress.

Anxiety is a relative phenomenon. Creating a hierarchy of behavioral and situational challenges gives you a list of much-needed laboratories within which you can experiment with your adrenaline. You are going to need as much practice with attaching and utilizing the Five-Step Adrenaline Control Technique as possible. Your investment in this belief will very much determine your degree of success with performance anxiety control. Experiment with the Five-Step one step at a time. Doesn't it make sense that if you are going to learn to control something you first have to feel or attach to it? (Adult)

The ideal strategy is to make the pursuit of your challenges gradual, consistent, and sustained. Create a hierarchy of the situations that make you nervous on a scale of 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest). These lists are different for each person. One client, for example, rated speaking one-on-one with his boss or other authority figures as a level 5; speaking to his sales team was a 7; the board of directors meeting was a 12 (on a scale of 1 to 10!) (See? That's a joke! [Natural Child]). For another client, participating in Toastmasters, a worldwide self-help program for public speaking, rated a 10. For still others, Toastmasters was only a 3 because she perceived the forum as a safe place to take risks. It's all subjective and relative. For some people talking spontaneously in a staff meeting is a 2; for others, a 9. You get the point. Create your behavioral hierarchy list of performance challenges now. It may take some thought. Do not continue with reading until you do this.

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

____________________________________________________

Before continuing with the next chapter, can you experiment with a level 2? Try it.

Close your eyes for a moment and identify how many windows there are in your kitchen. How did you get the answer? You pictured it with your mind's eye. You can use this technique to picture anything. This exercise can become an important tool for behavior rehearsal.

Now, do rhythmic breathing for 60 seconds. Pace your inhale–exhale at between 8 to 12 seconds—so that this 60-second exercise comprises about six inhale–exhales. Sixty seconds. I mean it. Do it. Next close your eyes and picture yourself implementing the Five-Step for a level 2. Stay with the image for about 20 seconds, and then open your eyes.

TUNE IN: What's the temperature of your hands? What thoughts and feelings are present?