I can drink a double espresso and go to sleep one hour later. My wife cannot drink coffee after 12 noon or she will not be able to sleep that night. Person A can smoke marijuana and sustain productive and creative energy for hours. Person B can smoke the same pot and have an anxiety attack or get depressed. Person C can have a glass or two of wine and leave it at that. Person D cannot stop drinking once he starts. Person E can take prescription medicine to ease nervousness and stop obsessing and gradually regain calmness and control. Person F can take the same medicine for the same reason and become agitated and more anxious. You get the picture. This is called "chemistry," and it varies from person to person.

Have you ever thought of your body as one big chemical reaction? The fact is, the human body undergoes hundreds of billions of chemical reactions every second. "The brain is fundamentally a chemical system," Susan Greenfield writes in The Human Brain: A Guided Tour. "Even the electricity it generates comes from chemicals. Beyond the fluxes of ions into and out of the neurons, a wealth of chemical reactions are occurring incessantly in a bustling but closed world inside the cell."

Indeed, the brain is a dynamic organ with properties and reactions to physical substances and neural stimuli. It's all in your head, remember? Inside your cranium are neurons, protoplasm, nerve cells, axons, dendrites, blood vessels, cerebrospinal fluid, and much more. These are the things that make up your mind—you didn't think the "mind" was an abstract entity, did you? It is a living organ that requires care and feeding—nurturing—to operate at its best. Nurturing brain health is the most important singular investment you can make to control your nervousness at work and beyond! Promoting healthy brain chemistry is an absolute must. Do everything you can to maintain the "hardware of your soul."

TUNE IN: Take in a long, slow, deep breath 1 ... 2 ... 3 ... 4 .... And exhaling 4 ... 3 ... 2 ... 1 .... One more time. Now look closely at the picture of the brain in Figure 7.1. Take your time. Consider this extraordinary organ. Notice how it is housed inside the head, behind the eyes, nose, and mouth that make up the human face. It is the seat of your senses, the source of your soul. Take in another long, slow, deep breath. Imagine the oxygen feeding your brain. Picture the neurons firing. After a minute or two, return to your reading.

Figure 7.1. The Brain: Patrick J. Lynch, medical illustrator; C. Carl Jaffe, MD, cardiologist. Used with permission.

Inside your head, behind your face, between your ears, is an extraordinarily powerful yet delicate machine. Do you see the complex, intricate, and potentially fragile makeup of the brain? Your brain is home to your knowledge, your memories, your hopes, and your dreams. It holds the secret to ending your anxiety and moving forward in life and your ability to perform successfully at work. Don't you want to do everything possible to ensure its health? Do you want to take chances by disrupting its chemistry?

Brain health is not merely mental health. A healthy brain requires the same healthy habits we all know about—good nutrition, regular aerobic exercise, and good, restorative sleep each night. When your neurons are firing properly, you are better equipped to balance your mind states when stressors arise.

Many of the substances people typically turn to in an effort to ease anxiety are actually at odds with optimal brain health: Alcohol, sugar and other foods, caffeine, tobacco, prescription and nonprescription drugs, marijuana, herbal remedies, and vitamins can all compromise brain chemistry. I am not saying you should not consume them—we'll talk more about that later. But it's time to understand their effects on brain health. Lack of exercise, air pollution, poor lighting, physical pain, repressed emotion—all of these affect the brain's chemistry. Chemistry is physical. It is not an abstract concept. Attach to the knowledge that your brain is affected by your decisions. Don't "should" on yourself if you have failed to protect it. This information is likely very new to you. The brain is a living organ that can heal itself quickly if you take the right actions. Stay present. Use your Adult's logic and objectivity. Now is the time to gather information so you can make a rational decision about the way you wish to care for your brain.

Evolving technology has led to a new understanding of brain functioning. For example, the MRI machine shows blood volume to different parts of the brain. The different degrees of volume are depicted by changes in color. With the individual who is a drug addict, blood volume is lower in specific areas. It is the same dynamic with anxiety. Therefore, one of the therapeutic objectives for anxiety management is to increase blood volume to the brain. Now, many activities will accomplish this—self-regulation/relaxation exercises, the healthy expression of emotion rather than repression, specific substances, both prescription and otherwise, brain-challenge exercises, and more. But the most direct way to increase blood volume to the brain is with quality aerobic exercise.

Do not avoid reading this section! If you are not a regular exerciser, you will be tempted to skip over this. But stick with me here. This is a critically important topic. Don't dismiss it by saying you've heard this all before or you know you won't follow these guidelines or you're thin or too busy or anything else. First of all, the guidelines are simple: Do something—walk outdoors, march in place, dance, or participate in a sport—for 20 minutes (or more) five or six times a week. (That's more than the three times a week recommended for basic heart and lung health—but this is your brain we're talking about!) The more you can oxygenate your brain, the better—not just for your anxiety but for your mood and brain power as well. If possible, get in the habit of doing your exercise outdoors—fresh air, Vitamin D from sunshine, a sense of solitude, and a chance to connect with nature will boost your spirits and leave you feeling grounded yet energized.

It's only 20 minutes a day—the length of a couple of coffee breaks or a phone chat. You can find the time. You must. Just 20 minutes of exercise at a moderate pace can mean the difference between mental (and physical) fitness and major imbalances that put you at risk of both more severe anxiety symptoms and heart disease and other illnesses. Not convinced those 20 minutes will be worth it? Read on.

Imagine a brain that scientific researchers would characterize as "biochemically, molecularly calm." A brain that functions at a higher level, able to fire its neurons for maximum performance. A brain that allows you to do your best, to be your best. Imagine a brain that is as fit as an Olympic athlete, able to adapt quickly and appropriately to challenging situations. A brain that uses the energy of adrenaline to fuel its excellence.

Aerobic exercise can give you that brain. Scientific studies indicate that exercise actually improves the brain's ability to handle stress. "It looks more and more like the positive stress of exercise prepares cells and structures and pathways within the brain so that they are more equipped to handle stress," Princeton University researchers report. "Exercise changes your brain for the better at a molecular level."

In the Princeton study, rats that were physically fit coped better with stress than those that were not. "Scientists have known for some time that exercise stimulates the creation of new brain cells (neurons)," the New York Times reported, "but not how, precisely, these neurons might be functionally different from other brain cells." The scientists found that the rats that exercised responded more calmly to stressful conditions than the rats that were kept on an exercise-free regimen. The brain cells they developed during exercise, the researchers said, were "specifically buffered from exposure to a stressful experience."

Hands down, aerobic exercise is the most effective technique for increasing blood flow to the brain. In fact, long-term research has shown that quality aerobic exercise is more effective in treating depression than antidepressant medication.

I must confess that I am addicted—to exercise. This addiction started during my senior year of college. In high school I was on the cross country and track teams. Although I was able to run a five-minute-four-second mile, I hated the pressure of the clock correlated to my running. In fact, I often succumbed to performance pressure. My senior year, in the first cross country meet of the season, I placed fourth out of about 35 runners. The next meet I placed last. I choked. It was in my final year of college that I really discovered aerobic exercise as a mood enhancer. At that time I was making it a point to run about five miles a day.

In my early 30s, I gave up running because of the stress it placed on my joints, but I kept up basketball. Now, at age 59, the additive stress on my back is taking its toll, but I am more addicted to the sweat than ever. I use aerobic exercise machines to get a workout that does not put stress on my ankles and knees; I have used a stationary bike and a Nordic track (I went through five of them), and now use an elliptical and stepper. I crave a good sweat. It gets my endorphins flowing. It greatly enhances my mood, self-esteem, and confidence, and helps me access my Adult mind state for problem solving. It has been and remains my therapy.

The power of sweating (via exercise) is enormous as it applies to anxiety management. Exercise-induced sweat rids the body of excess adrenaline and other biochemical activity associated with anxiety and panic. The key to creating a productive exercise program is to nurture yourself. This includes realistic expectations. If you proceed too quickly or intensely your inner child will have a temper tantrum (loosely interpreted) and will sabotage your efforts. Proceed with caution and a gradual methodology. Find the pace that works for you. It's better to reach quality objectives within a month's time than to try to get there within a week, find it too difficult, and stop. The more you can find an activity or sport that you genuinely like (Natural Child), the more potential you have to stay with it.

Your minimum therapeutic exercise objective for anxiety control is to work up to exercising three times a week for 20 minutes at your target heart rate. Measuring your heart rate is a simple form of biofeedback: observing information then taking targeted action in response to that information. To figure out your target heart rate subtract your age from 220, and multiply by 0.75 (e.g., if you are 40 years old: 220 − 40 years old = 180 × 0.75 = 135 beats per minute). Inexpensive pulse monitors are available. If you don't own a pulse monitor, here is a simple way to check your heart rate as you exercise: Place your index and middle fingers on a pulse point such as your wrist or neck. Using a stopwatch or clock, count the number of beats in 10 seconds and multiply by 10 to get your total. Alternatively, you can count for the full 60 seconds to determine your total. For more information on achieving your target heart rate during exercise, consult a reliable health Web site such as Discovery Health or Mayo Clinic. If you have any concerns about beginning an exercise program, consult your health care practitioner before you start—especially if you have not exercised in quite some time.

Take in a long slow deep breath and slowly exhale 4 ... 3 ... 2 ...1 ..., pacing your inhale–exhale. Inhale the oxygen and its energy. Exhale the carbon dioxide and tension. Inhale the energy. Exhale the tension. Do this three times, and settle into rhythmic breathing for a few moments.

Now I want you to access your mind's eye. How many windows do you have in the living room of your home? You will probably get the answer quickly because of the image imprint stored in your mind. You just used your mind's eye. Take in one more long slow deep breath and exhale 4 ... 3 ... 2 ... 1 ....

Read the following description carefully. Then close your eyes, using your mind's eye to create the image:

The oxygen-rich stream of blood is flowing through your right arm smoothly as the muscles around the blood vessels are relaxing, which opens the blood vessels up wide, allowing the blood to flow through with no resistance.

Focus on this image for two minutes as you breathe rhythmically. You may experience a tingling sensation. If so, embrace it. Next, the oxygen-rich stream of blood is flowing through your left arm smoothly as the muscles around the blood vessels are relaxing, which opens the blood vessels up wide, allowing the blood to flow through with no resistance as you continue to breathe rhythmically. Focus on the tingling sensation if present and the image for another two minutes. Then open your eyes and take a deep breath.

TUNE IN: Get a sense of your skin temperature and match it with your thoughts, feelings, and energy. Now do the exercise. The more you practice this, the better you will get with hand warming.

Getting enough sleep sounds easier than it is. Everyone has concerns that keep them up at night from time to time. But people who have anxiety about work have a lot of trouble making sure they get the right amount of prolonged, restorative sleep—the kind that lets you wake up refreshed and reenergized. How much sleep should you get? For most adults, seven to eight hours is about right. But the reality is that few of us establish the habit of getting that much sleep. I strongly recommend devoting eight hours to sleep. You need energy for all five mind states.

That simple habit can make a world of difference in the level of stress and anxiety you feel. Lorraine, age 42, was a teacher, opera composer, and singer who suffered anxiety about performing her own compositions on stage. Lorraine had a very busy life, teaching every day, private tutoring, correcting papers at night, and working on a major music composition that had to be finalized in two months. She continually told me she was burnt out. When she admitted she was sleeping only six hours per night, I advised her to get a full eight hours for two weeks straight—no matter what. After that "sleep experiment," Lorraine reported that she had more energy and enthusiasm for everything. "I'm getting so much done!" she said. "I have two hours less of awake time, but I get so much more done now when I am awake."

A highly creative teacher and musician, Lorraine expressed her feelings in a poem about her relationship with time:

Fighting with Time

I pick a fight with time each day, but time always wins.

No matter how I punch away, he deftly moves and grins.

No matter what clever plan I aim to break his chin,

His fists too strong, his legs too swift.

Time always does me in.

No matter what strength I fly,

Nor with what speed I run,

Time never stops to give me breath,

Or let me have my fun.

Oh, time, I cry, Can you not pause a moment, once you see?

But time does not listen.

He knocks the wind from me.

TUNE IN: Take the next two minutes. That's 120 seconds. Focus on your rhythmic breathing. Pace your inhale–exhale to at least 8 to 12 seconds. If you can extend this by a few seconds, it means you are getting better at it and taking more oxygen into your system. After your breathing exercise, focus on your skin temperature and resistance (perspiration) and match those sensations with your feelings and thoughts.

Doesn't it make sense that what you put in your body would directly impact chemistry? Doesn't it make sense to invest in creating a strong and healthy physiological foundation for anxiety control? Wouldn't you like to do all you can to create productive energy? Developing a healthy eating plan and taking responsibility for what you consume every day is a stress management essential—the first line of defense, before trying medication or natural supplements.

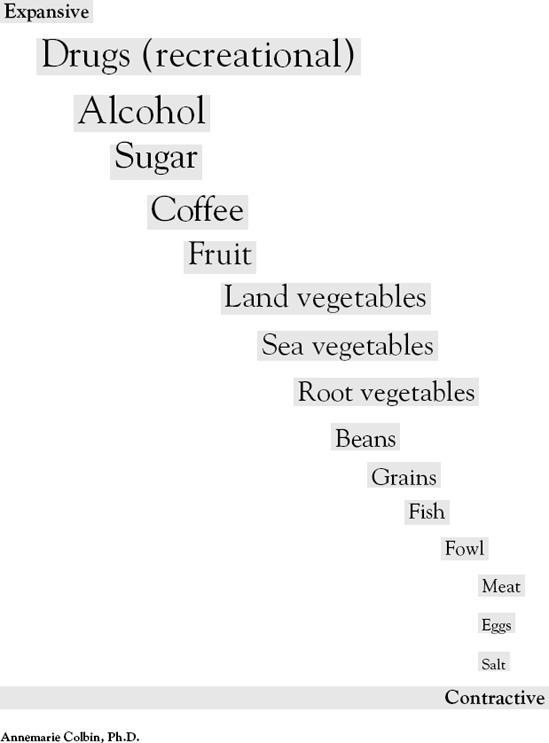

Annemarie Colbin, Ph.D., is author of the best-selling Food and Healing and founder of the Natural Gourmet Institute for Food and Health in New York City. Dr. Colbin served as a consultant for my Comprehensive Self-Therapy Audio Program entitled "Beyond Shyness: How to Conquer Social and Performance Anxieties."

Her theories about food and emotions are right in line with what I believe. For example, she sees the consumption of sugar as revealing an emotional need. "Sugar," she writes, "is closely related to feelings of alienation, despair, and depression." In my consultation with her, she put it even more simply: "Sugar is love." In my personal and professional life, I have seen so many parents who invest in loving their children with sugar. This can become a huge habit as we grow into adulthood and continue to associate sugar with love. And to complicate things, she noted, "Sugar is just about in everything."

Ensuring the right kind of food intake is a matter of balance. Indeed, Colbin's formula for mental health and anxiety management through eating is based on her belief that: "In the body balance happens with movement between opposites."

Just for a moment, imagine your body chemistry as a seesaw. When your food consumption is balanced, the seesaw is level. This is achieved by eating the right combination of "expansive" and "contractive" foods. The center foods are grains and beans and are the pivot point.

To determine whether you need "expansive" or "contractive" foods, you must determine whether your condition is expansive or contractive (spaced out or uptight). You can then choose foods to counterbalance that condition.

"There are no studies that show actual physiological data to support this model," Dr. Corbin says. "It is based on how foods feel to the eater. The foods correlate to psychological feeling."

From most expansive down to most contractive:

Confused |

Spacey |

Unable to concentrate |

Chatty |

Active |

Open |

Clear |

Concentrated |

Narrow-minded |

Mentally rigid |

Arrogant |

Fanatical |

Anxiety can be seen as a lack of focus and the inability to get grounded, therefore expansive; if anxiety leads to paralysis or extreme avoidance, it is contractive. To help restore balance, consume foods from the opposite side of the equation. For example, if the problem is rigidity, sweet fruits and warm drinks would have a relaxing effect; if the problem is a scattered condition, ingest salty and dry foods and avoid sweets.

The same general nutritional guidelines we all know so well are as critical for brain health as they are for the health of the rest of our bodies. Dr. Colbin's principles are simple: No refined sugar or artificial sweeteners. Only good quality, high-fiber carbohydrates. Plenty of protein. And balanced meals: Make sure that in each meal you have some protein, some whole grain carbohydrate, some fat (butter or olive oil are best), and some vegetables, especially leafy greens either cooked or raw.

People who smoke often reach for their cigarettes for stress relief. Apart from the obvious facts about smoking and the very serious health effects, you should know that smoking causes brain chemistry to undergo dramatic chemical changes. The resulting mood swings interfere with the ability to manage anxiety. Thus a smoker who hopes to alleviate stress is actually perpetuating it.

Ross, a 33-year-old horse farm manager, contacted me because of debilitating depression related to his workplace anxiety. He was at "an all-time low," he said, because he had learned that the breeding operation where he lived and worked had been sold. Although he had met several major players in the racing world, he had made no effort to establish business contacts. He was simply too uncomfortable talking to others, even just small talk. "I prefer the barn. I prefer the land. I went into this business to communicate with horses—not people!" He told me that his marriage had ended because, as his ex-wife said, he "never talked." Now, she was taking him to court for more child support—which he couldn't afford without a new job.

Ross confided that he was self-medicating with alcohol and prescription painkillers first prescribed to him when he broke his shoulder in the show ring. When I suggested augmenting therapy with a 12-Step program, he said, "Been there, done that. My problem isn't drinking, my problem is the reason I am drinking." Ross was willing to work extremely hard to beat his anxiety "habit"—and he was sure his dependence on drinking and drugging would diminish as he progressed. By the end of our work together, he had reduced his drinking by 80 percent and seldom even took aspirin. When he controlled his drinking, not only did his anxiety decrease but his ability to handle conflict increased dramatically. I have heard countless such reports.

In his first job out of college, Rick landed an investor relations position with a hip, young dot-com company. The casual work culture embraced a "work hard, play hard" ethic that meant lots of late nights, but also lots of after-hours and weekend parties. Rick did fine with the working-late part. But he was extremely nervous about the socializing. Most of Rick's colleagues brought dates to these events; Rick never did. In his initial session with me, he was both angry and despairing. "Jonathan, you have to help me! I feel like killing myself. I can't socialize. I can't get girls." Imagine how surprised I was just six weeks later when Rick told me he had received the holiday party award for "most social colleague." Strange, I thought. How was that possible? "Six-pack therapy," he said.

Despite its short-term anxiety-reducing effect, alcohol is a depressant and has a down side. This does not necessarily mean it will make you depressed (although with excessive drinking, clinical depression is often a byproduct). But it will sap (or depress) the energy you need for high performance and anxiety management. Never forget that a High Performance Mind requires all five mind states to function. Ongoing use of alcohol to take the edge off is the enemy of self-confidence and sustained proactive thinking and behavior. Drinking to dull your anxiety is defensive positioning! I am not referring to alcoholism—but to how you use alcohol, not how much alcohol you use or how often you consume it. Again, everybody has different chemistry, and I don't contend that "no alcohol allowed" is the only way to be healthy. But a strong caution is definitely warranted here.

Seth Mandel, M.D., a psychiatrist well versed in anxiety treatment and someone to whom I refer patients, offers this medical perspective on alcohol: "Despite the popular belief that alcohol is a social lubricant, the pharmacologic benefits of alcohol in humans have not been definitely proven. It is possible that the expectations of increased confidence and tension reduction accompanying alcohol intake may alone be able to override the fear of social situations."

Alcohol use might actually maintain or worsen social or performance anxiety for several reasons. Alcohol could block the experience of a sufficient fear response needed to adapt to such situations. The individual may also come to believe that the only reason he coped effectively with a given social event was because he drank. Increased anxiety can also occur following drinking due to physiological withdrawal and/or worries about social performance when under the influence of alcohol.

Lower doses of alcohol produce a feeling of stimulation, whereas higher doses produce sedation. The use of alcohol to cope with anxiety, while seemingly temporarily effective, is associated with an increased likelihood of additional mental health problems such as depression and possibly even suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Alcohol can be dangerous medicine for those with social and performance anxiety.

Here is my perspective on alcohol, based on 59 years of life and more than 30 years as a therapist. Moderate consumption of alcohol can enhance healthy NC behavior. It can even be therapeutic for "taking the edge off" occasionally. Make sure you have a realistic definition of "moderate." (My own definition is fewer than two units of alcohol [unit = one 4-oz. glass of wine, one 12-oz. beer, or one shot of hard alcohol] not more than four times a week.) Other health professionals, including Dr. Amen, say that more than one time a week is too much if you want to maintain optimal brain health. Saving your drinking allowance up for several drinks on a particular night is usually considered a "binge," which will only create distress for the brain. Alcohol is extremely insidious in that it can often entrap the drinker into dependence for mood control.

Is alcohol an issue for you? Use your Adult mind state to assess the quantity of your drinking. Some researchers claim that anything more than two units of alcohol (unit = one 4-oz. glass of wine, one 12-oz. beer, or one shot of hard alcohol) more than four times a week is more than "moderate" intake. But others, including Dr. Amen, who coined the phrase "the hardware of the soul" that we use in this chapter's title, disagree.

However much you may drink, stop to think about the times when you were consuming alcohol. Were you comfortable and relaxed? Were you hyper vigilant and in need of numbness or taking the edge off? Attach to your use of alcohol and, in doing so, attach to the situations that prompt your desire to drink.

I have studied marijuana extensively. I have seen some smokers use it to facilitate creative and positive energy. I have seen it help with pain and depression. I have seen it used to enhance recreational pursuits. I have seen positive things. But I have also seen unhealthy things. It depends on the chemistry of the user and the specific pot.

For example, at 22, Landon felt so inferior to the more experienced 20-something peers at his new job in the film industry that he quit. His parents sent him money to tide him over under the condition that he get professional help for his anxiety and depression. His physician prescribed medical marijuana. Landon was surprised to learn there were 70 brands to choose from. Some pot would bring him up and some would bring him down—but he wouldn't know which until he filled his prescription each time. The active ingredients acted on different parts of the brain.

A star baseball pitcher in high school, Tyler was one of the best players in his southern state and received a full scholarship worth $40,000 a year at a well-known university. In high school, he would usually pitch the entire game. His college team had five high-quality pitchers. Whenever Tyler was pitching, as soon as he let a man get on base, his coach would get another pitcher up in the bullpen. This practice threatened Tyler's confidence, and his negative critical script kicked into overtime. To cope with the stress of performance on the baseball field, he discovered marijuana. Smoking pot did help lessen the actual anxiety, but it also depleted his motivation and drive. Baseball held no appeal for him anymore. He dropped out of college and gave up his scholarship. Now, compare this to the thinking of Kirk Rueter, the major league pitcher we introduced you to earlier. Natural ability is not enough to attain or maintain a high level of athletic performance. It requires a High Performance Mind.

If you seek medical treatment to discuss whether you have a chemical imbalance, ask questions of the medical professional—ideally a psychiatrist or psychotherapist rather than a general practitioner, internist, or "family practice" physician. That person should consider various questions to determine what kind of imbalance is present; for example:

Do I have autonomic hypersensitivity?

Do I not have enough serotonin?

Do I have allergies?

Do I have a medical condition that would impact anxiety?

St. John's Wort. Cava Cava. Valerian Root. Camu Camu. Hops. Chamomile. California Poppy. All have been used to treat anxiety symptoms. There are many more—both individual substances and combination products. You can find them in natural food stores and online. Some offer stress relief, but also cause side effects including headaches, stomach discomfort, agitation, and oversedation. Natural pharmacology—nutritional supplements, herbal capsules, sprays, tinctures, and tonics—does not cure social and performance anxiety. Those products are tools to provide symptom relief only. Resolving anxiety lies not in masking those symptoms but in resolving emotions and thinking that cause the anxiety. You must go deeper and do the real work.

All told, the best approach is to rely on medicinal substances as little as possible, which is why the nutritional strategy of healing through eating makes a lot of sense. Eating is natural and structural. Do it right, and it may be the only nutritional supplement you need!

There are two natural dietary supplements that I think are worth considering (with your health care provider's approval, of course),

B-Complex Vitamins. Nutritional experts believe that the B-complex vitamins are especially important in warding off anxiety and depression. Among other things, they can reduce high levels of lactic acid in the blood, which are associated with anxiety and panic.

Inositol. I have recommended Inositol to more than 100 clients with performance anxiety who wanted to try a natural compound before going to prescription medicine. In the 1960s, Carl Pfeiffer, a pioneering physician and researcher, noticed that the brain waves of patients who took Inositol resembled those of patients taking Librium, a potent tranquilizer. Other studies are confirming Inositol's positive effects. Finding the right dosage for you may take some experimenting, starting with less then adding more to increase effectiveness as necessary. It may take several weeks before you attain maximum effectiveness. Inositol should not be mixed with prescription medication for anxiety or depression.

In my clinical practice, my philosophy has been to try to do therapy without medicine. I urge my clients to take responsibility for solving the problem as much as is possible. But when clients seems stuck, I may refer them to a psychiatrist for evaluation. I probably recommend medication for about 30 percent of my clients—but typically only for a limited amount of time as a way of facilitating deeper work and getting them "unstuck." When I raise the topic of medication, my clients sometimes ask me, "What about side effects?" And we discuss them. But I always counter with another question: "What about the side effects of being stuck with workplace anxiety? Diseased self-esteem? Poor performance reviews? Job loss?"

When I refer a client to a psychiatrist for medicine, it is with the understanding that that medicine is a tool to facilitate productive therapy, with the end result being that the person goes off the pharmaceuticals when a confident level of success has been achieved and sustained. That is our stated intention at the outset, and the prescribing psychiatrist must concur.

Christine, a 35-year-old woman working in middle management in a Boston corporation, contacted me to help her with anxiety about attending weekly managers' meetings. She and her partner, Jenny, were attending Toastmasters, which is a wonderful worldwide self-help program for public speaking. She told me that she was taking a beta blocker before her work meetings and before her Toastmasters engagements. Here is another unhealthy and unproductive use of medicine—after all, Toastmasters is a self-help organization intended to help members become more comfortable speaking in public.

Taking beta blockers regularly only allows you to detach from the adrenaline you fear. If you never feel that adrenaline, you have no laboratory. Avoidance is not an answer. If, however, you use them only occasionally, they can be a productive part of your recovery. Use medicine only to slow the rush so you can learn to handle it. Your goal is to anticipate the adrenaline as a good thing—as the fuel you need to succeed in stressful situations. If you can't feel it, you can't learn to access it as energy.

Of course, it's your decision, not mine. You will work with a prescribing physician and that person will no doubt weigh in on the pros and cons.

I recommended an SSRI to treat an assistant district attorney in Texas for her courtroom-specific performance anxiety and related obsessing, She found a psychiatrist who immediately prescribed an anti-anxiety medication, which had a sedating effect. Sedation not only prevented her from participating in treatment effectively, but it also severely compromised her work performance—exactly the opposite of what she was seeking! Eventually, she was prescribed an (SSRI, a type of antidepressant) with positive results. There are many such stories.

We live in an age of specialization; if you seek an evaluation for possible pharmaceutical treatment for social and performance anxiety, go to a psychiatrist or psychopharmacologist rather than a general practitioner. If you are seeing a therapist and you feel stuck, let your therapist know. You can discuss possible reasons why and raise the topic of medication as a potential part of your treatment.

A non-MD therapist can usually recommend a psychiatrist if prescription medication seems warranted. In any event, remember that your highest commitment is to progress and a cure—so don't languish with a practitioner whose treatment style is keeping you stuck.

I will recommend medication only when a person is invested in psychotherapy at the same time. I believe that when medicine is prescribed without concurrent counseling for social and performance anxiety, it is clinically criminal. When you hear medicine horror stories, you can bet that most of the time it was because the use of medication was not closely supervised. Medicine is not a cure for social and performance anxiety. It is a tool! It can have wonderful results when used correctly.

In this day and age, however, the pharmaceutical industry—and our own impatience as a culture—lead us to think there is a pill for everything. Every day, I get e-mails from people accessing www.socialanxiety.com, asking "What medicine do you recommend for social anxiety?" I do not bother to respond to these, because it would require quite a lot of information (as you will see), and those who are asking this as their first line of questioning are looking for a quick fix. The program outlined in this book is the quickest fix I know. Anyone wanting an insta-cure should be searching for a magician rather than a therapist.

The following is a Question and Answer section with Seth Mandel, MD, my psychiatrist colleague. Dr. Mandel is very experienced with prescribing medication to aid in the treatment of anxiety disorders. Medicating for anxiety is complicated, so careful evaluation and support are critical.

Question: What determines whether a workplace anxiety sufferer is a good candidate for medication?

Answer: For management of social and performance anxiety, I rely on criteria outlined in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR). Medication is generally deemed appropriate only if the avoidance, anxious anticipation, or distress in the feared social or performance situation(s) interferes significantly with the person's normal routine, occupational (academic) functioning, or social activities or relationships, or there is marked distress about having the phobia.

Question: What medications are typically prescribed for people who suffer workplace anxiety?

Answer: Social Anxiety Disorder is responsive to treatment with a variety of medications. The primary medications for this disorder are antidepressants, most commonly Selective Serotonin-Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs) including fluvoxamine (Luvox, Luvox CR); sertraline (Zoloft); paroxetine (Paxil Paxil CR); citalopram (Celexa); escitalopram (Lexapro); and fluoxetine (Prozac); and the Serotonin-Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine (Effexor XR), with the best evidence existing for escitalopram, fluvoxamine, fluvoxamine CR, paroxetine, sertraline, and venlafaxine extended release). Older classes of antidepressants, including the irreversible Monoamine Oxidase Inhibitors (MAOIs), such as phenelzine sulfate (Nardil), are also very effective. Less studied, but possibly effective agents [medications] include the SNRI duloxetine (Cymbalta) and the unique antidepressant mirtazapine (Remeron).

Benzodiazepines (sedatives or anxiolytics) can also be used for the treatment of social anxiety. Clonazepam (Klonopin) is an effective treatment for social anxiety. Alprazolam (Xanax) or lorazepam (Ativan) can also be used, but there is less scientific evidence behind this practice. [Author's Note: Klonopin and Xanax can be addictive, so proceed with caution, especially if there is a history of alcohol or other substance abuse.]

Anticonvulsants or antiepileptics are another class of drugs that has been used to treat social phobia. These medications include gabapentin (Neurontin) and Topiramate (Topamax).

B-adrenergic blockers may be effective in managing performance situations. Propranolol and Atenolol are two such medications. Atenolol is more selective for the heart and may not cross the blood-brain barrier easily, thereby limiting any central nervous system effects such as fatigue or depression.

Limited evidence suggests that augmentation of an SSRI with buspirone (BuSpar) may help to produce beneficial effects for patients with generalized Social Anxiety Disorder. The potential role of dopamine in underlying this disorder has led some researchers to investigate the use of atypical antipsychotics. Olanzapine (Zyprexa) and quetiapine (Seroquel) are two such medications.

Question: If you determine that prescription medications might help, how do you determine which medications to prescribe?

Answer: SSRIs and Serotonin Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors (SNRIs) are recognized as the first-line treatments for generalized Social Anxiety Disorder based on their efficacy, safety, and tolerability. They have been shown to be effective in numerous scientific studies. Social Anxiety Disorder may also be associated with other anxiety disorders such as Panic Disorder, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder, and Generalized Anxiety Disorder as well as mood disorders such as Dysthymic Disorder and Major Depressive disorder. These disorders are all responsive to treatment with SSRIs and SNRIs, lending further support to their use as the initial choice in the treatment of Social Anxiety Disorder.

Dose-equivalent head-to-head antidepressant studies have not suggested a difference in efficacy thus far. Medications are therefore often chosen on the basis of their side effect profile and potential utility in treating other possibly unrelated conditions. SNRIs also have usefulness in treating some pain conditions, including neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, and other chronic pain conditions, and also in treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

For patients whose anxiety is linked to a limited number of particular situations and is marked by symptoms such as increased heart rate and tremor, beta blockers may be effective taken approximately 30 minutes before an event. Despite widespread use, evidence supporting these medications (as an ongoing treatment) for performance anxiety is relatively weak.

Benzodiazepines [commonly called "tranquilizers"] taken on an as-needed basis may be useful in patients who have occasional bouts of moderate anxiety. Benzodiazepines work rapidly, whereas antidepressants can take weeks to obtain a full effect. They may be preferable to maintenance antidepressants for certain patients who have strong feelings about taking medication on a daily basis.

Benzodiazepines are not effective for mood disorders on their own and thus would require the use of a second medication in patients suffering from both conditions; like Klonopin and Xanax, they can be highly addictive and should be used with caution.

A combination of drugs may be prescribed to maximize therapeutic effects. SSRI treatment has been augmented by the addition of benzodiazepines, anticonvulsants, atypical antipsychotics such as risperidone or aripiprazole, or buspirone. Some patients with social anxiety do not experience any therapeutic benefit with SSRI or SNRI therapy; and the medications may be poorly tolerated. In these cases, it may be advisable to try an anticonvulsant or even an atypical antipsychotic such as quetiapine (Seroquel) or olanzapine (Zyprexa) as one drug only as opposed to a combination of medicines (it is more the norm to try an SSRI along with a benzodiazapene).

Question: How does a person weigh potential payoffs against possible side effects?

Answer. The use of any medication always involves an informed discussion between the psychiatrist and patient. There are risks and benefits to taking any medication, and the decision to take medication comes down to whether the potential payoffs outweigh any possible side effects from the medication.

As with all medications, side effects vary. Read about them and discuss them with your prescribing physician before choosing whether to begin pharmaceutical treatment.

I told you this would be complicated. The moral of the story is, use your NP and A. Clearly, prescribing medications to treat anxiety and depression is a high-level skill that is, in my opinion, best left to psychiatric specialists rather than general practitioners and internists, who usually do not have advanced and specialized training in these particular substances.

Take a moment to acknowledge yourself for an important accomplishment: Getting through this chapter. This was a lot to take in, and it no doubt gives you a lot to consider. If I've done my job, I have persuaded you that the care and feeding of the hardware of your soul is important and worthwhile. Pause now to center yourself.

TUNE IN: Take a long, slow, deep breath in, then out—for a total of 8 to 12 seconds. Oxygen in 1 ... 2 ... 3 ... 4 .... Carbon dioxide out 4 ... 3 ... 2 ... 1.... Concentrate on your rhythmic breathing for 30 seconds.

Now, using your Nurturing Parent and Adult mind states, write down three to six actions you will take for a healthy brain. For each one, give yourself a deadline by which you will take these actions. The brain likes definites—"By when?" is a good thing to think about.

Action I Will Take for a Healthy Brain | By When? |

|---|---|

1. _______________________________________________________ | |

_______________________________________________________ | |

2. _______________________________________________________ | |

_______________________________________________________ | |

3. _______________________________________________________ | |

_______________________________________________________ | |

4. _______________________________________________________ | |

_______________________________________________________ | |

5. _______________________________________________________ | |

_______________________________________________________ | |

6. _______________________________________________________ | |

_______________________________________________________ | |