The Rosetta Stone sat buried in the sand, forgotten and unloved, for nearly 2,000 years. There were no markers or maps that led Napoleon's army to find it on that day in July.[32] There was plenty of time for someone else to destroy, deface, chop it into pretty sculptures, or hide it where it could never be found. [33] Of course, we're fortunate that events turned out as they did, but back then, when the past was the present, there was every possibility for it to turn out differently. The discovery of the Rosetta Stone was not inevitable.

Yet, when we look at any history timeline, we're encouraged to believe, by their omission, that other outcomes were impossible. Because the events on timelines happened, regardless of how bizarre or unlikely, we treat them today as preordained. It's not our fault, and it's not the fault of timeline makers (as that's a tough job). The simple fact is that these simplifications make history easier to explain. That said, it's also deceptive: at every point in every timeline in every book that will ever be published, there was as much uncertainty and possibility for change as there is today.

Consider how technology is taught in ages: first there was stone, then bronze, then iron; or, in the computer world, it's the ages of mainframes, personal computers, and the Internet. We label periods of time around discoveries/inventions, projecting onto the past an orderly map to what was, normal, average, everyday confusion. The earlier adopters of bronze swords, chasing the wooden-spear-wielding masses away from their treasures, didn't see themselves as being in the "Bronze Age" any more than the first Macintosh users saw themselves as being in the "pre-Internet Age" or than we see ourselves as being in the "age before telepathy was cheap and fun" (or whatever amazing thing happens next). Like in the present, people in the past believed they had divorced themselves from history and were living on the edge of the future in a crazy place called now.

This leads to the divisive question, the terrifying test of awareness of innovation history: were the innovations of the past inevitable? Are the Internet, the automobile, and the cell phone the necessary and unavoidable conclusion of human invention up until this time? Many think so. The idea even has the fancy name techno-evolutionism, but as cool as that sounds, it's still wishful thinking. [34]

This misconception of technological evolution mirrors a fallacy about the evolution of life, the universe, and everything. The unspoken myth many place inside the theory of evolution is that it defines modern civilization as the best possible result of history, since we're still around. Many think of evolution as a pyramid or ladder, with humans at the top, the crowning achievement of the planet, or even the universe (see Figure 2-3). But evolutionary science doesn't support this; like the pre-Copernican solar system, putting us at the center or on top of everything sure sounds nice, but it's absurd.

Figure 2-3. Evolution means only that what's on top is fit for the current environment, not that it's "better."

Natural selection doesn't mean that what's on top is special, it means only that the current environment is favorable toward that thing. Watch the music charts: Johnny Cash's album Live at San Quentin was a bestseller when released in 1968. For decades it didn't make the top 50, but, in 2005, when a successful movie was released about Cash's life, the environment changed. [35] The album—the same exact recording made nearly 40 years earlier—flew back up the charts: the criteria for the fittest changed. Certainly evolution is more complex than pop music (I hope so), but the shifting nature of what is dominant is similar.

While humans might be dominant today (though the ever-resilient insect population most species depend on questions this [36] ), if the planet's temperature dropped by half, its nations blew everyone up, or a few medium-size asteroids crashed into the Atlantic, the fittest creatures won't be us. We'd be gone, best known by the surviving descendents of cockroaches as cute stuffed animals, in the same fashion we've eulogized our food chain-dominant predecessors, the dinosaurs.

I wish I had better news, but instead of a cozy timeline granting easy confidence in inevitable progress, there are no guarantees. The wonders of Greece and Rome didn't prevent our clumsy civilizationwide slide into the Dark Ages. Technologies are invented, lost, found, ignored, and then found again all the time. (For example, the secrets of concrete used in the Coliseum, shown in Figure 2-2, were lost when Rome fell, not to be rediscovered until the 1800s.[37] ) Carr goes on to say, "no sane person ever believed in a kind of progress which advanced in an unbroken straight line without reverses and deviations and breaks in continuity." The dilemma is that, at any moment, it's difficult to know whether we're witnessing progress or merely, in a hill-climbing distraction, a shortterm gain with negative long-term consequences. There have been many biological dead ends: more than 90% of all species in the history of the earth have become extinct, and that's after living for millions of years. [38]

Innovation follows: the reason we use mobile phones or personal computers isn't because they're necessarily better in the long run than smoke signals or cave paintings, or that they're at the top of an unshakable technology pyramid. [39] We've adopted these things gradually and intuitively as part of the experiment that is life. Simply because one thing has replaced another doesn't mean that it improves on it in every respect, and as conditions change, the notion of improved does as well. This hypothesis is easy to test: study the history of any innovation—from catapults to telegraphs to laser beams and nanotechnology—and you'll find its invention and adoption is based on ordinary, selfish, and mostly short-term motivations. Mistakes and complexities are everywhere, rendering a straight line of progress as a kind of invention itself.

Consider the gas-powered automobile, one of the most dominant technologies ever. In The Evolution of Technology, George Basalla explains:

There were no automotive experts at the turn of the century, only inventors and entrepreneurs following their hunches and enthusiasms and trying to convince potential car owners to buy their product. Given this situation, once the gasoline engine gained ascendancy, steamers and electrics were either forgotten or viewed as missteps along the road to automotive progress. [40]

Gasoline engines and automobiles were successful not because they'd lead us on the best path, or even because they were the best solutions for the problems of the day. They succeeded, in natural-selection fashion, due to the combined circumstances of that time. Traffic jams, pollution, road rage, and dependence on limited oil supplies all call into question the suitability of the innovation we still base our lives on.

Pick your favorite hot technology of the moment. How many different competing products are there? When an innovation is in progress, there are always competitors. Entrepreneurs are drawn to new markets because they have at least as good a chance as anyone else, even if they have less funding or experience. But what we forget is that every innovation, from a jet aircraft to a paper clip, was once an open, competitive, experiment-rich playing field.

In Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation, James Utterback writes:

It would be tempting to think that there is some predetermination to the emergence of dominant design—that automobiles with internal combustion engines were somehow exactly what the gods of transportation always meant for us to have, and that earlier experiments with electric and steam powered cars were misguided aberrations destined to go nowhere. The emergence of a dominant design is not necessarily predetermined, but is the result of the interplay between technical and market choices at any particular time. [41]

And don't forget the negative influence of the six-pack of human shortcomings: greed, irrationality, short-sightedness, egotism, lack of imagination, and just plain stupidity. It's quaint to think cars have seatbelts or antilock brakes because of the monk-like rationality, forethought, and good spiritedness of our innovation predecessors, but it just isn't so. [42]

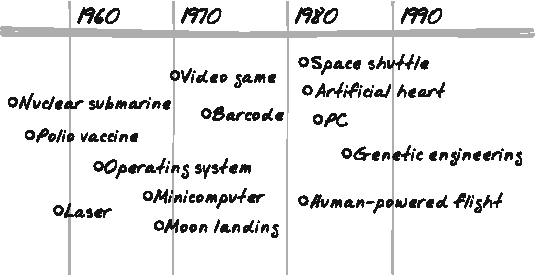

This means that every technology, from pacemakers to contact lenses, fluorescent lights to birth control pills, arrived through the same chaos seen in the hot technologies of today. Just because dominant designs developed before we were born, or in fields so far from our own that we're ignorant of their struggles, doesn't mean their arrival was predictable, orderly, or even in our best interest. Yet, the dominant designs, the victors of any innovative pursuit, are the ones that get most of history's positive attention (see Figure 2-4).

In Figure 2-4, you can find a single blip in the 1980s representing when the personal computer (PC) came into existence. It's entirely polite and well behaved sitting there. You'll notice it doesn't take up more space than its neighbors, and it seems happy with its lot in life, perhaps sharing afternoon tea with its interesting friends the artificial heart and genetic engineering. But if we zoomed in, increasing the resolution so that the history of the PC was more than a single spot on a timeline, we'd see a chaotic, competitive, and unpredictable tangle of events. That happy little dot is a shill in the unavoidable deception that are timelines. Not only do timelines express a false omnipotent view of history, they're superficial, offering an illusion of comprehensiveness. History is deep, and, like a fractal, you can find much to see at different layers. Let's dig in and see where that little dot for the PC goes.

When the development of the PC began in the late 70s, there were many possibilities for how (and even if) it would be delivered to the world. Mainframes were the dominant design, and only a curious minority believed computers would be in people's offices, much less their homes. Apple Inc.'s 1977 release of the Apple II computer is credited with proving that there was a viable market for personal computers. However, Xerox PARC (a research institute at the copier company) developed an earlier personal computer, the Alto, in 1973. The door for the Apple II's success was opened when two things happened. First, two leading companies, Atari and Hewlett-Packard, rejected Apple's proposal to manufacture its computer for them. [43] Second, Xerox chose not to market the Alto, despite having plans in hand. Both facts seem stupid today, but that's hindsight talking; in most cases, Atari, Xerox, and HP made reasonable business decisions given the time.

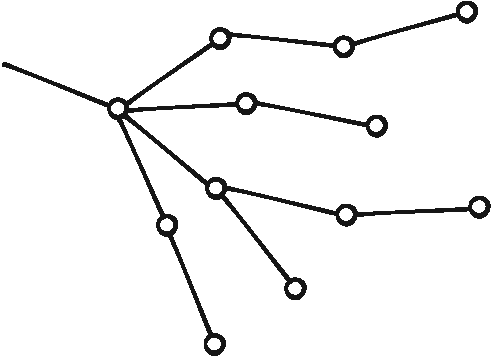

If you made a rough sketch of the possibilities of personal computing in 1980, you'd have something like Figure 2-5. Unlike the timeline in Figure 2-4, the graph shows how many different possible simultaneous directions were pursued, each one challenging, inspiring, and feeding off the other. But the timeline hides all this action—the juicy chaotic details innovators need to understand.

And since the timeline must show a single date for the PC, the year 1983 was chosen: not 1973 (Alto), 1977 (Apple II), or 1979 (Atari 400). In 1982, the PC was popular enough for Time to name it Man of the Year (suggesting, perhaps, that I could run for gadget of the decade, though I suspect I won't be asked), but it was later on, around 1983, that the IBM PC was the true dominant design. The dot on the timeline is an amazing averaging of knowledge: it can't even hint at when the idea of the personal computer was first explored, or at the struggles the unnamed pioneers of innovation had to overcome with electricity, mathematics, and transistors to pave the way for Apple, Atari, and IBM to finish things off decades later. [44]

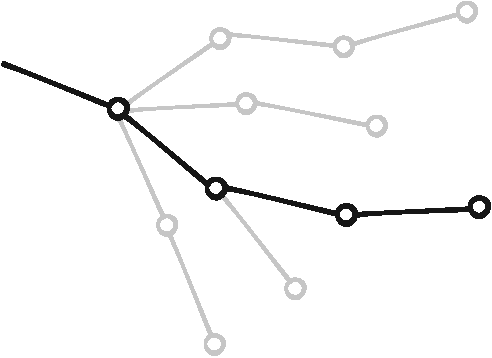

While the IBM PC did become the dominant design, we have to be careful about drawing conclusions about why. It was never preordained, nor did it come solely because of IBM's monopolistic dominance (they would release the comically stillborn PCjr soon after). [45] It's worth considering what would have happened if Xerox had chosen to release its Alto, or if Apple had convinced Hewlett-Packard to bankroll their machine: IBM would not have had the same opportunity. In the other direction, had Xerox or IBM taken risks earlier, the PC timeline might have shifted forward, but without lessons learned from watching competitors, it's possible that their immature products, launched before the technology or the culture was ready, could have set back the timeline until 1985 or 2005 (see Figure 2-6).

Many innovations, such as the development of the web browser almost 20 years after the PC, follow similar patterns of innovation. The first popular web browser was NCSA's Mosaic, released in 1993 for the Windows operating system (the dominant-design OS for the dominant-design IBM PC). Within two years, there were over a dozen competitors in the browser market; by 1997, the count was over 40. [46] In those early years, browsers were so prolific that other software, like word processors or games, often included a web browser made by that company. By 1997, two dominant players remained, Netscape Navigator and Microsoft Internet Explorer (disclosure: I worked on this product from 1994–1999), and they competed in what was grandly named the browser wars, with Internet Explorer becoming the dominant design by 1999. Few alternatives were popular until 2005 when the release of Mozilla Firefox—a reinvention of Netscape Navigator—started a new wave of interest and innovation in browser competition.

At this level of detail, there are many interesting questions. Why didn't the browser wars last longer? Did those years of intense competition work in the best interest of consumers, or are there more opportunities now, with an aging dominant design in place, for browsers like Firefox and the respectably resilient Opera product to take larger risks and push another wave of innovation forward? And on it goes. The history behind personal computers and web browsers alone involves many books' worth of stories, decisions, inspirations, and surprises impossible to represent here, much less in one happy timeline-bound dot. [47] My point is that there are hundreds of similar dots on any timeline, at any scale, each with its own fascinating stories and lessons. You can zoom in on the story of, say, Apple, and again on any product or person involved, and find an entirely new set of insights and inspirations. (Try www.folklore.org for a fantastic start.)

But enough about history: it's one thing to explore why innovations of the past grew to dominance, but it's something else to innovate in the uncertainty of the present, which we'll explore next.

[32] E. A. Wallis Budge, The Rosetta Stone (Dover, 1989), http://www.napoleon-series.org/research/miscellaneous/c_rosetta.html.

[33] One story related to Napoleon and Egypt is that his army was responsible for the destruction of the Sphinx's nose. This tale is definitely a myth: there are drawings of the damaged nose that date decades before Napoleon's Egypt visit.

[36] Edward O. Wilson, The Diversity of Life (Belknap Press, 1992).

[37] Dick Teresi, Lost Discoveries (Simon & Schuster, 2002).

[39] A simple review of misconceptions about evolution: http://evolution.berkeley.edu/evosite/misconceps/IBladder.shtml.

[40] George Basalla, The Evolution of Technology (Cambridge University Press, 2002).

[41] James Utterback, Mastering the Dynamics of Innovation (Harvard Business School Press, 1996).

[42] Ralph Nader's 1965 book, Unsafe at Any Speed (Grossman), revealed how collusion in the automotive industry prevented innovations in safety. See http://www.answers.com/topic/unsafe-at-any-speed.

[44] A better, though still simple, timeline of the events that led to the personal computer can be found at http://inventors.about.com/library/blcoindex.htm.

[46] A concise history of web browsers can be found at http://www.livinginternet.com/w/wi_browse.htm. For a deeper history of the hypertext systems web browsers were born from, see Jakob Nielsen, Multimedia and Hypertext: The Internet and Beyond (Morgan Kaufmann, 1995).

[47] For Xerox PARC, see Michael Hiltzik, Dealers of Lightning: Xerox PARC and the Dawn of the Computer Age (Collins, 2000); for Macintosh, see Steven Levy, Insanely Great: The Life and Times of Macintosh, the Computer That Changed Everything (Penguin, 2000); and generally, Paul Freiberger and Michael Swaine, Fire in the Valley: A History of the Personal Computer (McGraw-Hill, 1999).