By definition innovation is a charge into the unknown.

—Unknown

Every Tuesday morning, Mr. K., my chemistry teacher, stumbled into the high school science lab, unlocked the chemistry cabinet, and built the most destructive science experiments known to man. He would repeat these pyrotechnic feats, ignoring scorched desks and terrified students, until he passed out or ran out of ammunition. After demanding that we replicate his chemical prowess, he'd storm out of the room, rarely seen until the following week. I haven't lost my fear of Bunsen burners and glass vials, but I remember one concept important to all innovative pursuits that those experiments etched into my mind: methodology (see Figure 3-1).

A method, as defined by the American Heritage Dictionary, is a systematic way of accomplishing something. I deduced from Mr. K.'s behavior in class that no matter how late a person was out on a given night, or how many bars he visited before sleeping in his car, if he faithfully followed the methodological formulas of chemistry, he could achieve the same results repeatedly without risk. Despite threats to the contrary, no students were ever harmed in his presence. The immutable laws of science, Mr. K. proclaimed, are all powerful, as they have a consistency beyond everything known to man.

But life is larger than science. What we want in life is more complex than what can be achieved by mixing smelly powders or dropping Mentos into large bottles of Diet Coke (do try this, but do it outside). [48] And unlike school assignments, we don't want the same results every time. To innovate is to make something new, and progressive science—the discovery of knowledge—is a far cry from what went on in Mr. K.'s classroom. A true experiment has at least one variable that is unknown, and the experiment is to see how that variable, well, varies. What happens if you juggle magnetized bowling balls under water or deep fry a sack of Twinkies in space? If no one knows for certain, you have an experiment on your hands.

While it's one thing to come up with a new idea, a second to try it out and see how it works, it's a less interesting third to follow safe, well-practiced instructions that someone—perhaps a pyromaniac teacher—has laid out for you. Real experiments have risks, just like real life: consider Marie Curie, who discovered radiation but died from it, or the millions of lab rats put out of their cheesy misery every year in the name of exploring new ideas. Innovating comes at a price: it might be money, time, sanity, friends, or marriages, but there will definitely be one.

The myth of methodology, in short form, is the belief that a playbook exists for innovation and, like Mr. K.'s deceptively quaint instructions, it removes risk from the process of finding new ideas. It's the same wish that fuels secret lusts for timesaving gadgets, tasty but low-fat meals (ha), and five-step programs for <insert problem here>. And like other myths, this fantasy sells faster than truth, explaining the films, novels, and infomercials that play on it.

But in our better minds, the one disappointingly easy to fool out of its credit card numbers, we know the impossible never happens. We know it's not called the if-you're-lucky-possible or the if-you-read-a-fancy-book-it-may-work-possible for good reason. There is no way to avoid all risks when doing new things. It takes resources to start a company, develop an idea, or even change someone's mind, and those investments have no guaranteed returns. Even the scientific method, the process behind the ubiquitous "rocket science," doesn't promise success—consider the Apollo 13 mission or the Challenger space shuttle. And methods created by gurus or famous executives all fall well short of predictive; the greatest innovators in history all have more failures in their records than successes. There is good advice to be found, but it's a far cry from methodology.

The top question famed innovators hear is, "How did you start?" It's the beginnings that drive our curiosity: when did Edison get the idea for the lightbulb, or how did the Google founders envision a better search engine? Everyone wants to know where the magic happened, and since they can't imagine the magic sprinkled across years of work, they assume it's a secret—a tangible, singular element hiding behind the start. Like our endless quest to explain the origins of things, we're prone to seeking magic in beginnings.

It's this desire that leads otherwise bright minds to research Michael Jordan's breakfast, da Vinci's or Einstein's napping habits, or Linus Torvalds' (founder of Linux) chosen style of underwear. [49] The irrelevance of these details is obvious here in the logical confines of this book, but we've all considered similarly ridiculous questions about someone we admire. I once researched which typewriter Hemingway had and which inks Shakespeare used to pen his plays. Dreams don't run on logic: when we follow our emotions, we find both amazing and ridiculous things, and it takes time to sort one from the other.

The eventual problem with excessive, dreamy curiosity is that— instead of making our own beginnings, right here and now—we seek to reuse others' magic, borrowing their beginnings, retrofitting them into our lives. [50] Of course, still safe in this book, we know details from others' experiences are unlikely to be pivotal in our own—what worked for them, during their era, won't necessarily work for anyone else. For example, imagine that Alexander the Great was born in Iceland or Steve Jobs in medieval France— how well would their "magic" work? There are countless factors in any success story, and only some belong to the innovators.

Bo Peabody, venture capitalist and founder of Tripod (the eighth largest web site in 1998) wrote, "Luck is a part of life, and everybody, at one point or another, gets lucky. But luck is a big part of business life and perhaps the biggest part of entrepreneurial life." [51] Acknowledging the uncontrollable factors helps divorce us from worshiping the details of heroes' achievements. Studying history grants power, but only when we overcome romance and see innovators as humans just like us with similar limitations and circumstantial influences.

The best advice I've read on starting creative work comes from John Cage, the most innovative composer of the 20th century, who said, "It doesn't matter where you start, as long as you start." [52] He meant that there can be no perfect beginning: it's only after you start—no matter how roughly—that you can evaluate and build on what you've done, shift directions, or start over with the insight and perspective you've gained in the process. Innovation is best compared to exploration, and like Magellan or Captain Cook, you can't find something new if you limit your travels to places others have already found.

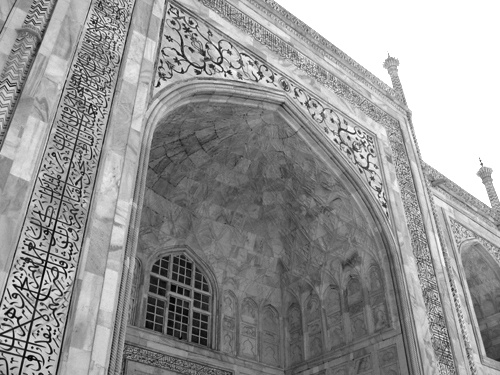

The clichés about beginnings are true. The history of innovation is large enough that all the sayings, from Plato's famous "Necessity is the mother of invention" to Emerson's "Build a better mousetrap and the world will beat a path to your door" hold some truth.[53] The trap, and the myth, is that evidence supporting one claim doesn't mean there isn't equally good evidence supporting another. Invention, and innovation, have many parents: the Taj Mahal (Figure 3-2) was built out of sorrow, the Babylonian Gardens were designed out of love, [54] the Empire State Building was constructed for ego, and the Brooklyn Bridge was motivated by pride. Name an emotion, motivation, or situation, and you'll find an innovation somewhere that it seeded.

Figure 3-2. Constructing the Taj Mahal required several innovations, all inspired by an emperor's sadness for his deceased wife.

However, it's simplifying and inspiring to categorize how things begin. In reading the stories behind hundreds of innovations, some patterns surface, and they're captured here in six categories. I concede to the existence of reasonable arguments for seven or five, or different categorizations altogether. I offer this list to seed your thoughts on what paths to innovation are in front of you now.

The majority of innovations come from dedicated people in a field working hard to solve a well-defined problem. It's not sexy, and it won't be in any major motion pictures anytime soon, but it's the truth. Their starts are ordinary: in the cases of DNA (Watson and Crick), Google (Page and Brin), and the computer mouse (Englebart), the innovators spent time framing the problem, enumerating possible solutions, and then began experimenting. Similar tales can be found in the origins of the developments of television (Farnsworth) and cell phones (Cooper).[55] Often, hard work extends for years. It took Carlson, the inventor of the photocopier, decades of concentrated effort before Xerox released its first copying machine. [56]

Many innovations start in the same way as mentioned previously, but an unexpected opportunity emerges and is pursued midway through the work. In the classic tale of Post-it Notes, Art Fry at 3M unintentionally created weak glue, but he didn't just throw it away. Instead, he wondered: what might this be good for? For years he kept that glue around, periodically asking friends and colleagues whether it could be useful. Years later, he found a friend who desired sticky paper for his music notations, giving birth to Post-it Notes. Teflon (a mechanical lubricant), tea bags (first used as packaging for loose tea samples), and microwaves (unexpected discharge from a radar system) all have similar origination stories. What's ignored is that the supposed "accident" was made possible by hard work and persistence, and it wouldn't have otherwise happened by waiting around.

Many innovations begin with bright minds following their personal interests. The ambition is to pass time, learn something new, or have fun. At some point, the idea of a practical purpose arises, commitments are made, and the rest is history. George de Mestral invented Velcro in response to the burrs he found on his clothes after a hike. He was curious about how the burrs stuck, put them under a microscope, and did some experiments. Like da Vinci, he found inspiration in the natural world, and he designed Velcro based on the interlocking hooks and loops of the burrs and his clothing. Linus Torvalds began Linux as a hobby: a way to learn about software and explore making some of his own. [57] Much like the direction-change scenario, at some point, a possible use is found for the product of curiosity, and a choice is made to pursue it or follow curiosity elsewhere.

Many innovations are driven by the quest for cash. Peter Drucker believed Thomas Edison's primary ambition was to be a captain of industry, not an innovator: "His real ambition…was to be a business builder and to become a tycoon." [58] Drucker also explains that Edison was a disaster in business matters, but that his profile was so prominent that—despite his entrepreneurial failures—his management methods are emulated today, particularly in Silicon Valley and venture capital firms.

With half an innovation in hand, ideas but no product, it's natural to try to sell those ideas: let someone else take the risks of complete innovation. Instead of idealistic goals of revolution or changing the world, the focus is on reaping financial rewards without the uncertainties of bringing the ideas all the way to fruition. The Internet boom and bust of the 1990s was driven by start-up firms innovating, or pretending to innovate, just enough for established corporations to acquire them. In many cases, the start-ups imploded before acquisition or were acquired only for their ideas to be abandoned by the corporations' larger and conservative business plans.

The founders of many great companies initially planned to sell their ideas to larger corporations but, unable to sell, reluctantly chose to go it alone. Google tried to sell to Yahoo! and AltaVista, Apple to HP and Atari, and Carlson (photocopier) to nearly every corporation he could find.

Waves of innovation have come from individuals in need of something they couldn't find. Craig Newmark, founder of Craiglist.org, needed a way to keep in touch with friends about local events. The simple email list grew too popular to manage and evolved into the web site known today. Similarly, the founders of McDonald's developed a system for fast food production to simplify the management of their local homespun hamburger stand (Ray Crok bought the company later and developed it into a multinational brand). Innovations that change the world often begin with humble aspirations.

Most innovations involve many factors, and it's daft to isolate one above others. Imagine an innovation that starts with curiosity and leads to hard work, but then the innovator's quest for wealth forces a direction change. Midway through, this direction change is interrupted by a stroke of good luck (say, winning the lottery), allowing the innovator to return to the initial direction with renewed perspective and motivation. The removal of any of those seeds from the story might end it—or might not. In many of the stories of innovation, we have to wonder: if the first "magical" event didn't take place, might the innovator have found a different seed instead? No matter what seeds are involved, all ideas overcome similar challenges, and studying them reveals as much or more than the beginnings of innovation.

[49] I don't know what kind of underwear Linus wears, but my guess is he goes commando: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linus_Torvalds.

[50] "Until one is committed, there is hesitancy, the chance to draw back—Concerning all acts of initiative (and creation), there is one elementary truth that ignorance of which kills countless ideas and splendid plans: that the moment one definitely commits oneself, then Providence moves, too. All sorts of things occur to help one that would never otherwise have occurred. A whole stream of events issues from the decision, raising in one's favor all manner of unforeseen incidents and meetings and material assistance, which no man could have dreamed would have come his way. Whatever you can do, or dream you can do, begin it. Boldness has genius, power, and magic in it. Begin it now." —Goethe

[51] Bo Peabody, Lucky or Smart (Random House, 2004).

[54] The Babylonian Gardens are a disputed entry in the Seven Wonders of the World; they may never have existed: http://ancienthistory.suite101.com/article.cfm/the_hanging_gardens_of_babylon.

[55] Singular inventorship is exceptionally rare, as we'll discuss in Chapter 5. For all of these innovations, others rightfully claim partial credit. Several books have been written on the history of television, and it's one of the most complex and distributed stories of innovation in the 20th century.

[58] From Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 13.