To open minds and find good ideas, return to the kid in the park. What is it about his attitude that allows fearless idea exploration? Linus Pauling, the only winner of two solo Nobel Prize awards in history, had this to say about finding ideas: "The best way to have a good idea is to have lots of ideas." This sounds idiotic to most ears because it cuts against the systematic, formulaic, efficiency-centric perspective worshiped in schools and professions. It seems wasteful to follow Pauling's advice. Can't we just skip to the good ideas? Optimize the process? Memorize a formula to plug stuff into? Well, you can't.

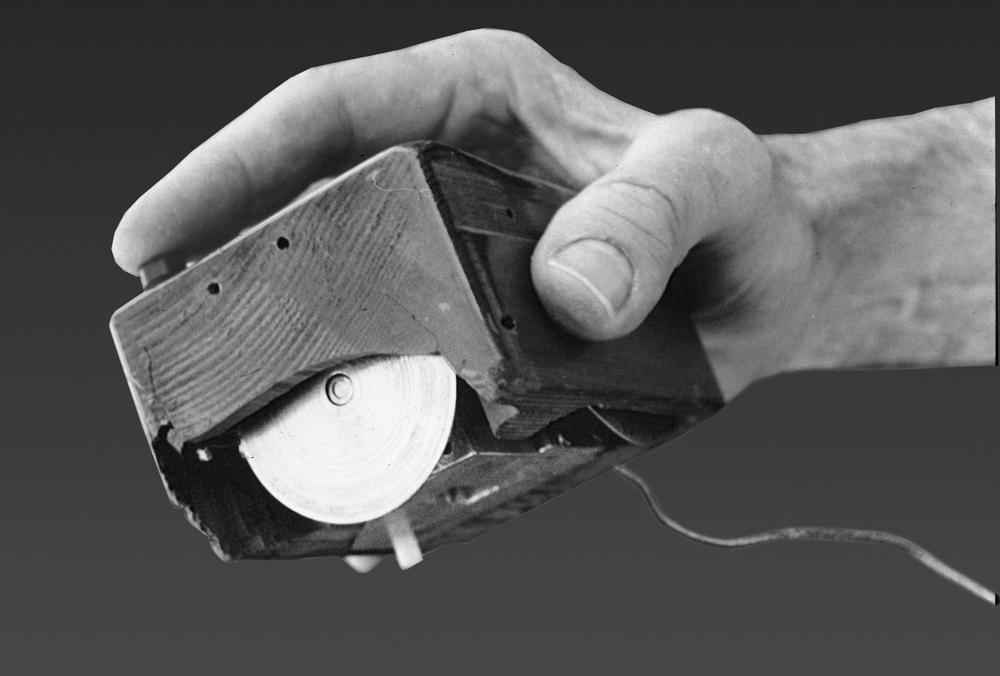

Figure 6-2. The superficials of innovation are rarely impressive. This is a version of the first computer mouse.

The dirty little secret—the fact often denied—is that unlike the mythical epiphany, real creation is sloppy. Discovery is messy; exploration is dangerous. No one knows what he's going to get when he's being creative. Filmmakers, painters, inventors, and entrepreneurs describe their work as a search: they explore the unknown hoping to find new things worth bringing to the world. And just like other kinds of explorers, the search for ideas demands risk: much of what's found won't be satisfactory. Therefore, creative work cannot fit neatly into plans, budgets, and schedules. Magellan, Lewis and Clark, and Captain Kirk were all sent on missions into the unknown with clear understanding that they might not return with anything, or even return at all.

The lives of well-known creative thinkers are filled with compulsions for playing with ideas: they wanted wide landscapes to explore. Beethoven obsessively documented every idea he had, madly scribbling them on tree trunks or on the manuscript paper he had jammed into his clothing, even interrupting meals and conversations to scratch them down.[111] Ted Hoff, the inventor of the first microprocessor (Intel 4004) used to tell his team that ideas were a dime a dozen, encouraging them not to obsess or fixate on any particular one until a wide range of ideas had been explored. Hemingway made dozens of rewrites and drafts, changing plots, characters, and themes before he published his novels. WD-40 is named because of the 40 attempts it took to get it right (Dr. Ehrlich's cure for syphilis, called Salvarsan 606, was similarly named). Picasso used eight notebooks to explore the ideas for just one of his paintings (Guernica); if you watch the film The Mystery of Picasso, you can watch the master exploring ideas, good and bad, in real time as he creates dozens of paintings (see Figure 6-3). [112]

Figure 6-3. Many artists use canvases to explore ideas as they paint— they're not painting by numbers, but exploring and making mistakes as they create.

The list goes on. In any field, creatives are those who dedicate themselves to generating, working, and playing with ideas. Pattie Maes, director of MIT Media Lab's interactive group, explains:

Most of the work that we do is like this. We start with a half-baked idea, which most people—especially critical people— would just shoot down right away or find uninteresting. But when we start working on it and start building, the ideas evolve. That's really the method that we use at the Media Lab…in the process of building something we often discover the interesting problems and the interesting things…that leads to interesting discoveries.

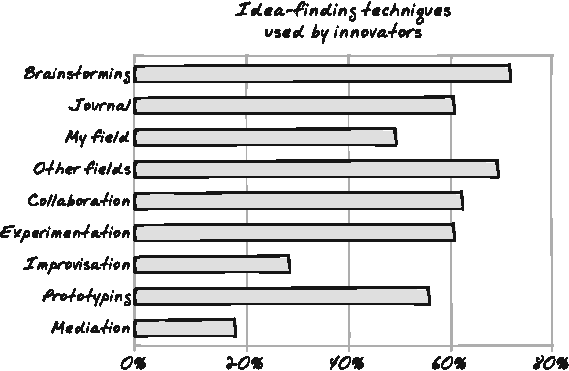

There is further support for an innovator's desire to seek out new ideas. In a recent survey, innovative people—from inventors to scientists, writers to programmers—were asked what techniques they used. Over 70% believed they got their best ideas by exploring areas they were not experts in (see Figure 6-4). [113] The ideas found during these explorations often sparked new ways to think about the work in their own domain. And since they didn't have as many preconceptions as the people in that field, they could find new uses for what were seen as old ideas. Doctors studied film production; writers read biographies of painters. Any pool of ideas, no matter how foreign, could become a new area of discovery for an open mind.

Figure 6-4. Based on a recent online survey of over 100 self-identified innovators in various fields.

Like the child in the park, creativity is intertwined with the ability to see ideas as fluid, free things. Ideas come, they go, and that's OK; to an open mind, ideas are everywhere (something I'll prove momentarily). It's the willingness to explore, experiment, and play, to invest energy, hit a dead end, and then chase a new direction that allows minds to find good ideas. All of our notions of play, and its freedoms from formal judgment, are inexplicably linked to finding good ideas.

[111] Edmund Morris, Beethoven: The Universal Composer (HarperCollins, 2005).

[112] The film The Mystery of Picasso (Dir. Henri-Georges Clouzot, Image Entertainment) is a classic of art schools everywhere. Few artists, much less legends, were as open to documenting their process as Picasso, as demonstrated by this film. Make sure to listen to the DVD commentaries, as they provide more insight than the spare soundtrack. See http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0049531/.