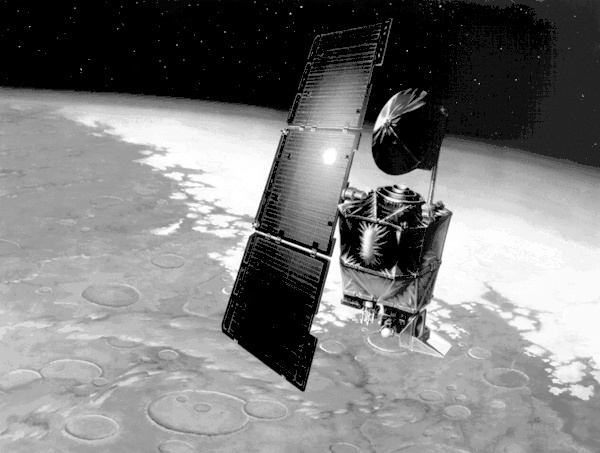

On September 23, 1999, NASA's $300 million Mars Orbiter, flying through space millions of miles from Earth, fired its engines to slow it into orbit around Mars. Its 10-month journey complete, the craft flew silently above the Martian sky at a leisurely 12,000 miles per hour. It followed all its programmed instructions and was, as planned, turning behind Mars' dark side, disappearing for the first time. The command staff waited expectantly for the Orbiter, 10 years in the making, to reappear on the other side (see Figure 8-1). Ten minutes later, well past its expected timeline, it had not arrived. Mission control feared the worst. They searched the Mars atmosphere but there was nothing: the Orbiter was gone.

They'd learn later that the spacecraft entered the wrong orbit, flying too low. Instead of a routine trip around the planet, it approached at a deadly angle and was destroyed in the atmosphere. What took longer to understand was the cause. Somehow, somewhere, an equation failed to convert units from metric to English, and the $300 million Orbiter was sent on a path of certain destruction. It was doomed before it even launched.

Figure 8-1. The poor little Mars Orbiter. Had Jefferson succeeded, the craft might have survived its trip to Mars.

As is always the case, this failure had many causes. The Orbiter was part of the "Faster, Better, Cheaper" initiative at NASA to accelerate innovation by removing processes in the name of creative freedom, but it simultaneously increased risks—a common dilemma for managers of innovation (speed cuts both ways). But one link in the chain of failures is the metric system itself: why does the world, and particularly the U.S., still use two different systems of measurement?

The metric system has been in use for over 200 years. It's used by 190 of the 193 nations on this planet, and it has many advantages over the English system (explained shortly). [143] Cans of soda, like Coke or Pepsi, still list both English and Metric measurements (12 oz/354 ml) as an odd testament to a token compromise of policy—and a good idea ignored. Even the United Kingdom, the home of the English (foot/gallon/mile) system, moved on to metrics decades ago.

The American story of metrics, a tale of proposed and denied innovation, begins with Thomas Jefferson. While serving as Secretary of State, he innocently proposed to the U.S. Government that they replace the English measurement system. [144] It's an odd mess of ad-hoc measurements from the Babylonian, Roman, and Saxon royalty, and it wasn't a system so much as a pile of half-baked traditions and blindly followed rules (see Inheritance and tradition in the previous list). The yard, for example, was defined by the length of the belts worn by kings (had they not been so rotund for their day, who knows what size our football fields would be). Endorsed by English monarchs through the ages, the system was adopted without question by the American colonies. But Jefferson was smart and a free thinker. He knew it wouldn't be hard to design a better system, and that it would be a great value to the new nation. He got to work and soon had a plan similar to what would be called metrics by France years later.

He divided the English foot into ten units called lines, and divided lines into ten units called points. Using tens, decimal math, made perfect sense to him as an easy way to convert between unit sizes. (Quick: how many ounces in a gallon? Cups in a quart? We have 10 fingers, and base-10 math makes many operations easy.) He made a similar decimalization of larger measures; adjusted the size of the foot, yard, and mile to fit scales of 10; and proposed this plan to Congress in 1789. Everything was great. He probably imagined decimalizing everything from units of time to expressions of love. The promise in young Jefferson's mind must have been high.

The proposal landed with a thud (approximately 4.5 kilograms of force per cubic centimeter). Congress didn't so much reject his plan as starve it to death: the idea was ignored (see Politics: who benefits?, Economics, and Short-term vs. long-term thinking in the previous list), and time went on. Across the Atlantic, the metric system was ratified in France in 1793 and spread over the decades into Europe's dominant system (although it was a slow, rocky process). [145] The opportunity for metrics to become dominant had much to do with the French Revolution, which ended just before metrics were ratified. As a general lesson, large innovations, say, political revolution, bring with them many smaller changes for better or for worse. The metric system rode the wave of political innovation in France in a similar way to how the QWERTY keyboard rode the wave of technological innovation of the typewriter.

In 1866, the U.S. had no choice but to respond despite passing on the same idea 50 years earlier. Congress took action, but it was far from decisive. They drafted an act stating it was now legal—not required or encouraged, but legal—for people to use the metric system if they chose. [146] With promotion like that, how could the metric system lose? That's like a parent telling a child they're now allowed to clean their rooms thrice a day. Few Americans were moved, and the English measurements remained. There was little motivation for individual business owners to convert their equipment, no matter how much better Jefferson—or any objective thinker on the subject of measurement—thought of the matter. Several more anemic attempts were made to promote metrics, including the requirement for foods to be dual-labeled with metric and English measures (thus the soda cans), but to this day, no further effort has been made.

Some think situations like metrics in America need a forced hand: the only way a leap can be made is by mandate. For fun, imagine that you had evidence that replacing the QWERTY keyboard with a different design would create world peace or guarantee survival of the human race. What would have to be done to replace it around the world? In a single large country? In less than six months? Tasks like these are difficult because the costs of change are astronomical. Unless, like QWERTY's adoption, there is a larger wave of innovation that takes a replacement for QWERTY with it (or as is popular in sci-fi films, does away with keyboards entirely), it'd be hard to make any progress at all.

Some innovations—such as safety systems in automobiles or environmentally safe home construction (e.g., asbestos free)—succeeded only because governments provided incentives or penalties as motivation (in some cases, making the dominant design illegal). How else can progress happen in situations where the collective benefit for a society is greater than the perceived benefit for individuals? (For example, mandated elementary school is good for nations, but unpopular with children). However, some believe that forcing the hand of innovation goes against the nature of free markets and often backfires. The truth is complex; sometimes forcing innovation adoption works, and sometimes it doesn't. The best lesson in all cases is that success is defined more by the factors listed previously than by who is pushing the innovation—and how hard they're pushing it. Having $50 million to market a product means little compared to the forces of culture, dominant design, and politics.

To fully apply those factors to this example, the English system was the dominant design. While metrics had advantages, no one convinced the American politicians or people why the costs of making the changes were worth the effort. Thinking politically, what interests would be served by a businessman or a politician making the switch? And after Jefferson left office, why wasn't anyone willing to lead the charge for his proposal? The minority of those who benefited were set free after the 1866 act, but anyone on the fence never received incentive for change.

[143] As you'd expect, there is no end to the debate over the relative merits of English and metrics, as well as the costs of switching in the U.S. For details on international use of the metric system, see http://lamar.colostate.edu/~hillger/. For pro and con arguments, check out these sites: http://www.metric4us.com/ and http://ts.nist.gov/WeightsAndMeasures/Metric/mpo_home.cfm

[144] Here's Jefferson simple proposal: http://www.yale.edu/lawweb/avalon/jeffplan.htm.